Published online Feb 28, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i8.2475

Peer-review started: August 11, 2014

First decision: August 27, 2014

Revised: September 15, 2014

Accepted: November 19, 2014

Article in press: November 19, 2014

Published online: February 28, 2015

Processing time: 202 Days and 6.1 Hours

AIM: To evaluate the efficacy and long-term outcome of infliximab combined with surgery to treat perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease (CD).

METHODS: The work was performed as a prospective study. All patients received infliximab combined with surgery to treat perianal fistulizing CD, which was followed by an immunosuppressive agent as maintenance therapy.

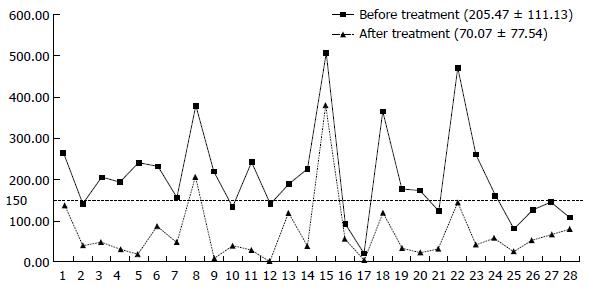

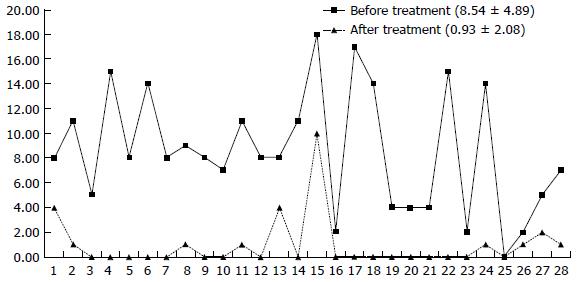

RESULTS: A total of 28 patients with perianal fistulizing CD were included. At week 30, 89.3% (25/28) of the patients were clinically cured with an average healing time of 31.4 d. The CD activity index decreased to 70.07 ± 77.54 from 205.47 ± 111.13 (P < 0.01) after infliximab treatment. The perianal CD activity index was decreased to 0.93 ± 2.08 from 8.54 ± 4.89 (P < 0.01). C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, platelets, and neutrophils all decreased significantly compared with the pretreatment levels (P < 0.01). Magnetic resonance imaging results for 16 patients after therapy showed that one patient had a persistent presacral-rectal fistula and another still had a cavity without clinical symptoms at follow-up. After a median follow-up of 26.4 mo (range: 14-41 mo), 96.4% (27/28) of the patients had a clinical cure.

CONCLUSION: Infliximab combined with surgery is effective and safe in the treatment of perianal fistulizing CD, and this treatment was associated with better long-term outcomes.

Core tip: Infliximab (IFX) combined with surgery for the treatment of Crohn’s disease (CD) anal fistula has significant effects, improves the clinical cure rate, and shortens the fistula healing time. Our findings indicate that IFX combined with surgical treatment is the reasonable treatment for anal fistulas in CD and that the normal ranges of CD activity index and C-reactive protein do not mean the endoscopic healing.

- Citation: Yang BL, Chen YG, Gu YF, Chen HJ, Sun GD, Zhu P, Shao WJ. Long-term outcome of infliximab combined with surgery for perianal fistulizing Crohn's disease. World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(8): 2475-2482

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i8/2475.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i8.2475

Since Bissell[1] first reported regional enteritis of the small intestine accompanied by perianal granulomatous lesions in 1934, perianal lesions in Crohn’s disease (CD) have received increasing attention from clinicians. Anal fistula is the most common perianal lesion in CD, and its incidence has been reported as high as 17%-43%[2-4]. After the diagnosis of intestinal CD, the incidence rates of anal fistula within 1, 10, and 20 years were 12%, 21%, and 26%, respectively[5]. Patients with active lesions in the colon have a significantly higher incidence of anal fistula; the incidence of anal fistula in the presence of rectal involvement is 92%, and only 5% of CD patients first manifest anal fistula in the absence of intestinal inflammation[5,6]. Anal fistulas in CD are typically more complex and affect the anal sphincter complex. Surgical treatment can easily damage the ability to control defecation, and postoperative wound healing is difficult.

Due to the development of the disease itself and the underlying pathological changes, therapeutic strategies for fistulizing CD involve both medical and surgical approaches, but they have largely unsatisfactory results. Infliximab (IFX) (RemicadeTM, Centocor Inc., Malvern, Pa., United States) is a murine chimeric monoclonal antibody against tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α. It is the first Food and Drug Administration approved biological drug for the treatment of CD, and it is the first drug confirmed by randomized controlled studies that can promote CD anal fistula closure and sustain the disappearance of symptoms for up to one year[2,7]. The World Gastroenterology Organization has recommended the intravenous infusion of IFX as the first-line therapeutic drug for CD patients with anal fistula[8]. However, there are fewer studies on IFX combined with surgery in the treatment of fistulizing perianal CD[9-12], and data on the long-term outcome are even more rare.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness and long-term outcome of IFX combined with surgery to treat perianal fistulizing CD beyond 1 year in a cohort of patients in a tertiary hospital of China.

We prospectively enrolled the patients with perianal fistulizing CD who received surgery combined with IFX therapy in the Department of Colorectal Surgery at the Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine from March 2010 to May 2012. We excluded patients with a gland-derived or tuberculous anal fistula. All included patients were free from IFX contraindications (severe infection, active tuberculosis, moderate to severe cardiac insufficiency, liver dysfunction, renal dysfunction, cancer, and nerve demyelination). The study was not submitted for the approval of the research and ethics board because IFX use is normally employed in this setting, with licensed or published doses and frequencies. All patients underwent clinical examinations and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to determine the type of fistula and endoscopy for evaluating colorectal inflammation.

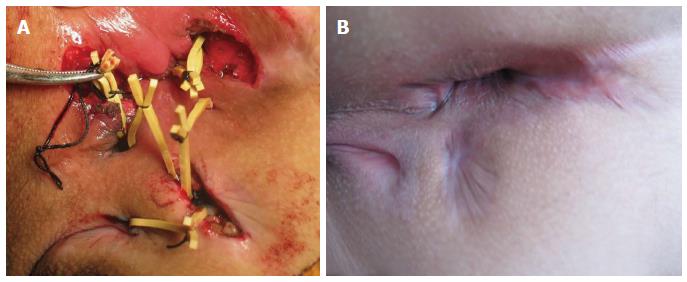

Surgery was performed in the prone jackknife position under combined spinal and epidural anesthesia. According to MRI and examination under anesthesia (EUA), we defined the fistulas as simple or complex. Simple fistulas were defined as low (subcutaneous, intersphincteric, or transsphincteric, involving less than 1/3 of the external sphincter) with a single external opening, lacking pain or fluctuation and lacking evidence of rectal strictures, which were treated by fistulotomy. Complex fistulas were defined as high (high intersphincteric or transphincteric, involving 1/3 of the upper external sphincter, suprasphincteric or extrasphincteric) with either multiple external openings associated with pain or fluctuation suggestive of a perianal abscess or anorectal stricture. Complex fistulas were treated with the sphincter-retaining and loose-seton drainage therapy (Figure 1). The specific procedures were as follows. We clarified the position of the internal opening and relationship between the fistula and anal sphincter based on the preoperative MRI examinations and intraoperative hydrogen peroxide test. A radial incision was made along the primary tract of the anal fistula from the internal opening towards the external side. The internal opening was excised, and the original infection foci were cleaned by scraping. The fistula tract on the external side of the anal sphincter and the lateral branches were radially incised in several places. Necrotic tissue within the fistula was removed by scraping, and rubber bands were used to loosely connect the incision of the main tract and various other drainage incisions, resulting in reliably sustained drainage. For patients with fistulas affecting the retrorectal space, a silicone tube was placed in the retrorectal space for drainage, and it was removed after two weeks. We simultaneously treated associated lesions, such as skin tags and anal fissures.

After the operation, the wound was flushed with metronidazole solution, and the dressing was changed daily. When the wound showed good growth of granulation tissue, the secretion disappeared, and if there was resistance to flushing the sinus or pulling the rubber band, the drainage rubber band was gradually dismantled.

All patients received induction therapy by the intravenous infusion of IFX (at weeks 0, 2, and 6; 5 mg/kg), and the first infusion (week 0) was started within the first week after surgery, which was followed by three administrations of maintenance therapy, performed at eight-week intervals. The patients received oral administration of 10 mg of loratadine on the night before and received an intravenous bolus infusion of 5 mg of dexamethasone 15 min before the infusion of IFX. During the infusion process, electrocardiographic monitoring was performed to observe and record the patient reactions to the infusion. At the fourth IFX infusion, a concomitant immunosuppressive agent [azathioprine (AZA)] was routinely co-administered. After IFX infusion was stopped, 27 patients successfully were then given AZA (2 mg/kg per day) maintenance therapy, and 1 patient who was intolerant of AZA was treated with thalidomide (100 mg/d).

All patients were clinically evaluated before each IFX therapy by the same surgeon, and the data were stored in a database. We assessed the patients’ therapeutic results at the sixth (30th week) IFX infusion. The closure of the external opening of the anal fistula and disappearance of secretions for three months or more was considered indicative of a clinical cure; a reduction in the number of fistula tracts, fistula size, secretions, and discomfort was considered as remission; persistent anal fistula was considered as ineffective treatment; and recurrence of active inflammation/perianal abscesses was classified as recurrence. The degree of inflammatory bowel disease activity was evaluated using the CDAI[13]. A CDAI reduction of more than 70 compared to the pre-treatment level was considered effective, and CDAI < 150 was considered as remission. Perianal lesions were assessed using the perianal CD activity index (PDAI)[14]. The hematological tests included routine blood examination and measurements of the alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, total protein, albumin (ALB), urea nitrogen (Bun), serum creatinine, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and CRP levels. All of the above indicators, as well as the body mass index (BMI) and colonoscopic examination, were evaluated at both weeks 0 and 30. We recorded adverse events at any time during the treatment, including the time of occurrence, frequency, severity, treatment measures, and outcome. Due to the need for maintenance therapy for intestinal inflammation, the patients came to the hospital once every two months to adjust their maintenance therapy drugs and undergo follow-up examinations.

We used the SPSS19.0 software for statistical analyses. The measurement data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and the count data are expressed as frequencies or proportions. Missing values were not included in the statistics. Measurement data with normality and homogeneity of variance were examined using the t-test, and measurement data with non-normality or heterogeneity of variance were examined using the Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test in nonparametric statistics. Count data were examined using the χ2 test.

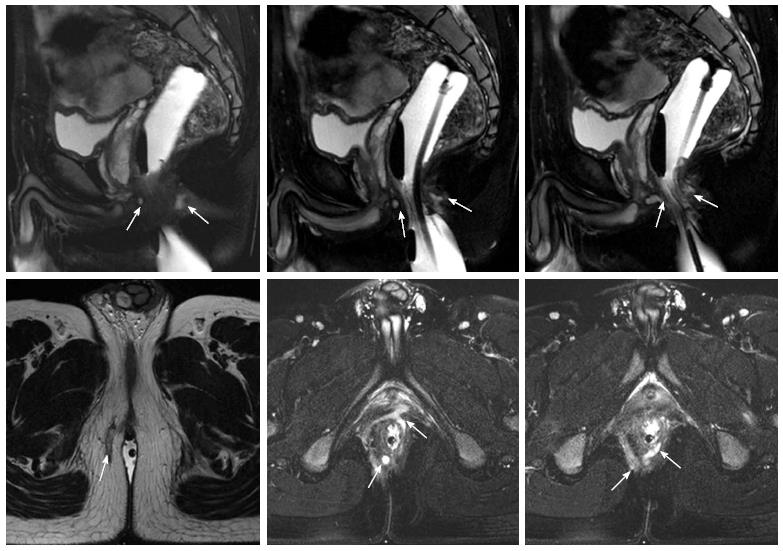

A total of 28 CD patients with anal fistula were included in this study (23 males and 5 females). The mean age was 25.9 ± 6.9 (range: 13-36) years, and the median follow-up time was 26.4 mo (range: 14-41 mo). The fistulas of all patients were evaluated by pelvic MRI before surgery, and there were 23 complex fistula cases and five simple fistula cases (Figure 2). The general information on the patients is provided in Table 1.

| Gender ratio (male:female) | 23:5 |

| Age (yr) | 25.9 ± 6.9 (13-36) |

| Mean follow-up (mo) | 26.4 (14-41) |

| Surgical history | |

| Hemorrhoidectomy | 1 (3.6) |

| Perianal abscess drainage surgery | 10 (35.7) |

| Anal fistula surgery | 15 (53.6) |

| Previous medical therapy | |

| Corticosteroids | 6 (21.4) |

| Immunomodulator therapy | 2 (7.1) |

| Infliximab | 1 (3.6) |

| No therapy | 19 (67.9) |

| Lesioned intestinal segment | |

| Ileum | 8 (28.6) |

| Colon | 4 (14.3) |

| Ileocolon | 14 (50.0) |

| Unable to assess | 2 (7.1) |

| Types of fistula | |

| Simple | 5 (17.9) |

| Complex | 23 (82.1) |

| Concomitant perianal diseases | |

| Skin tag | 4 (14.3) |

| Anal fissure | 5 (17.8) |

| Anorectal stenosis | 4 (14.3) |

| Other associated symptoms | |

| Stomach pain | 18 (64.3) |

| Diarrhea | 13 (46.4) |

| Anemia | 7 (25.0) |

| Fever | 4 (14.3) |

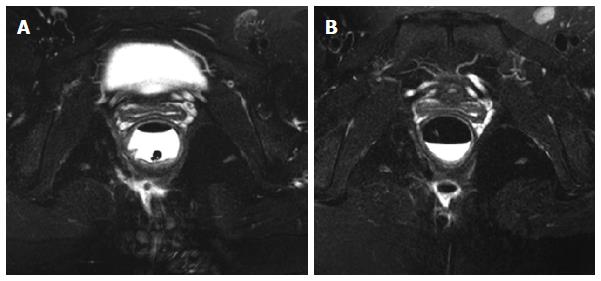

At the 30th week after the IFX treatment, 89.3% (25/28) of the patients had a clinical cure of the fistula, and the average healing time was 31.4 (20-45) d. Two patients had fistula recurrence and were cured after reoperation; another one had a fistula between the rectum and presacral space, and there was abscess formation due to local infection during IFX treatment. This patient had to be treated by long-term seton drainage. Anorectal stenosis in four patients improved significantly, allowing for the passing of the index finger during a digital rectal examination. Sixteen patients underwent an MRI examination after the 30th week, and 14 patients showed complete fistula track healing. Inflammation in the patient with a rectal-presacral fistula was controlled, but fistula remained. Another patient did not show any clinical symptoms at the end of the follow-up (34 mo), in spite of the existence of a limited cavity in the postanal space (Figure 3). Over a mean period of 26.4 mo (range: 14-41 mo), 27 (96.4%) patients still maintained a clinical cure, except for the patient with a rectal-presacral fistula.

After the completion of IFX treatment (the 30th week), the clinical symptoms of patients were significantly controlled. For all patients at week 30, the mean CDAI was significantly reduced compared to baseline from 205.47 ± 11.13 to 70.07 ± 77.54 (Figure 4) and the PDAI from 8.54 ± 4.89 to 0.93 ± 2.08 (Figure 5) (P < 0.01 for both). CRP decreased from 20.66 ± 18.55 to 5.77 ± 5.17, and 82.1% (23/28) of the patients returned to the normal level (< 10 mg/L); ESR decreased from 28.53 ± 19.61 to 9.25 ± 7.36. The patients showed significant improvement in their nutritional status; the BMI score increased from 18.52 ± 2.84 to 21.36 ± 2.94, and ALB increased from 39.68 ± 5.93 to 43.10 ± 3.89. Compared with the pretreatment levels, the white blood cell counts (WBCs), percentage of neutrophils, and levels of hemoglobin and platelets showed statistically significant changes, although the levels remained within the normal ranges (Table 2). Endoscopic re-examination confirmed that 27/28 patients showed significantly improved intestinal inflammation, and only one patient achieved complete mucosal healing.

| Before treatment (week 0) | After treatment (week 30) | t value | P value | |

| CDAI | 205.47 ± 111.13 | 70.07 ± 77.54 | 9.974 | 0.000 |

| PDAI | 8.54 ± 4.89 | 0.93 ± 2.08 | 8.590 | 0.000 |

| BMI | 18.52 ± 2.84 | 21.36 ± 2.94 | -6.447 | 0.000 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 25.61 ± 22.8 | 5.20 ± 5.39 | 4.244 | 0.000 |

| ESR (mm/h) | 25.29 ± 17.64 | 11.10 ± 6.9781 | 4.700 | 0.000 |

| HB | 121.21 ± 16.40 | 129.57 ± 17.64 | -3.985 | 0.000 |

| WBC (× 109/L) | 7.27 ± 2.90 | 5.29 ± 1.41 | 3.713 | 0.001 |

| N (%) | 68.45 ± 8.69 | 52.39 ± 10.74 | 8.677 | 0.000 |

| PLT (× 109/L) | 267.88 ± 99.92 | 196.10 ± 63.22 | 4.441 | 0.000 |

| ALB | 39.68 ± 5.93 | 43.10 ± 3.89 | -2.778 | 0.010 |

Two (7.1%) patients experienced adverse reactions during the IFX treatment. One patient showed sudden cyanosis, rapid breathing, and reduced blood pressure during the 3rd IFX infusion, indicating an acute infusion reaction. The symptoms were eased after oxygen inhalation, termination of IFX infusion, and intravenous administration of 5 mg of dexamethasone. One patient had sudden bilateral lower extremity weakness on the day after the 3rd infusion of IFX. The hematology results showed decreased serum potassium (2.1 mmol/L), and the patient returned to normal after two weeks of oral potassium supplementation. Most patients had mild drowsiness on the same day after the IFX infusion and typically recovered on the next day.

The best treatment for CD anal fistulas remains controversial. The results for the surgical treatment of anal fistulas in CD have been disappointing with unpredictable recurrence[15]. The appropriate surgical treatment should consider the type of fistula and degree of activity of inflammatory bowel disease. Poritz et al[16] analyzed 29 reports related to CD anal fistulas, and the postoperative healing rate of complex CD anal fistulas was 0%-100%, recurrence rate was 0%-75%, and chance of requiring rectal resection was 0%-60%.

Studies have shown that IFX is important in the treatment of CD anal fistulas[2,17]. In the ACCENT II trial, 306 CD fistula patients received intravenous infusions of 5 mg/kg IFX at weeks 0, 2, and 6. Fourteen weeks later, 195 (69%) patients with effective treatment results were randomized into a maintenance treatment group, given 5 mg/kg IFX every eight weeks, and a placebo group. At the 54th week, only 36% of the patients in the treatment group showed fistula closure, while the rate for the placebo group was 19%[2]. Ng et al[18] reported 26 CD fistula patients treated with infliximab (n = 19) or adalimumab (n = 7), and clinical fistula closure was seen in 46% patients at follow-up. However, MRI showed complete healing in only 30% at 18 mo. On the other hand, long-term maintenance treatment with IFX can promote closure of the external opening of an anal fistula as well as increase the incidence of abscesses. Although it remains controversial whether we should use surgery, drugs, or surgery combined with drug therapy to treat CD anal fistulas, preliminary clinical studies have shown that thread-drawing drainage combined with IFX is better than surgery or IFX alone[19-21]. In this study, the intravenous infusion of IFX was started within one week after surgery. At the 30th week, 89.3% (25/28) of the patients showed clinical healing of the anal fistula, 7.1% (2/28) required reoperation, and only one patient had a persistent fistula. The average fistula healing time was 31.4 d, and compared with other reports of thread-drawing drainage alone or IFX therapy alone, the cure rate was significantly improved, and the fistula healing time was significantly shortened[12,22]. Another study confirmed that IFX had efficacy for inflammatory bowel stricture but was ineffective for fibrotic stricture[20,23]. In this study, the four patients with anorectal stenosis showed significantly improved stenosis, allowing for the passage of the index finger. However, these four patients showed varying degrees of decline in the ability to control defecation due to sphincter damage caused by the disease itself and the symptoms of irritation caused by rectal inflammation.

Hyder et al[19] have shown that IFX combined with surgery is safe and effective for treating CD anal fistulas, but the clinical cure rate of long-term (with a mean follow-up of 21 mo) maintenance treatment is only 18%. In this study, patients were followed for an average of 26.4 mo, and 27/28 (including 2 patients who underwent reoperation) of the patients were clinically cured. We think the main reasons are as follows: (1) preoperative MRI examination effectively prevented overlooking hidden foci of infection during surgery; (2) the internal openings of primary infections were treated as much as possible during the surgery; (3) we decided whether to remove the drainage rubber bands based on the growth conditions of the drainage wound: If the drainage rubber bands are removed too early, it often leads to poor drainage and subsequently to abscess formation, while, in contrast, the long-term placement of drainage rubber bands can lead to fistula fibrosis, preventing fistula closure; (4) some patients might still have residual cavities without presenting with obvious clinical symptoms considering that postoperative MRI showed that 1/16 of the patients still had clear cavities, but no obvious clinical symptoms were found when they were followed for 34 mo; and (5) an immunosuppressive agent for maintenance of remission is necessary.

With the clinical application of biological therapy, the treatment goal for CD has changed from the remission of clinical symptoms alone to healing of the intestinal mucosa[8,24]. It has been shown that IFX can achieve healing of the intestinal mucosa in approximately 30% of patients[25,26]. During our follow-up study, only one patient had complete healing of the intestinal mucosa at the 30th week, although the remaining patients showed significantly improved intestinal inflammation. CDAI and CRP are important indicators for monitoring the level of intestinal inflammation activity and CD recurrence[27]. After induction therapy with the intravenous infusion of IFX, the CDAI and CRP values of most patients decreased significantly and remained at low levels, suggesting that IFX can effectively control the intestinal inflammation. However, according to our findings, when patients are in the normal ranges for CDAI and CRP, they have undergone mucosa healing.

It has been reported that intravenous IFX infusion might result in severe adverse reactions[28,29]. Zabana et al[28] reported the application of IFX therapy for the treatment of 152 inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients; 13% of patients had infusion reactions, 13% had bacterial or viral infections, and 1.3% developed cancer. The overall mortality was 2.6%, which was not significantly different compared to the group without drug treatment. The findings of another study, performed over a period of 14 years, are consistent with the above conclusions[26]. In this study, 28 patients underwent a total of 168 IFX infusions; one patient had severe infusion reactions; one patient had hypokalemia after infusion, which was not listed in the drug instructions; and no significant damage in the liver and kidney functions was found, suggesting that the safety of IFX infusion is controllable. However, the WBC and neutrophil percentage showed different degrees of decline after treatment, and the differences were statistically significant, suggesting that IFX infusion has a certain degree of bone marrow suppression.

This study has certain limitations. In addition to its small sample size, the fact that it was performed at a single center and was a nonrandomized study is a limitation of this study. On the other hand, the follow-up time of the study was short. A larger, randomized, multicenter prospective trial to validate these results should be performed.

In conclusion, we found that IFX combined with surgery for treating perianal fistulizing CD had significant effects in controlling intestinal inflammation, improving the clinical cure rate, and shortening the fistula healing time. Additionally, the use of an immunosuppressive agent as maintenance therapy was associated with better long-term outcomes in Chinese people.

Anal fistula is the most common perianal lesion in Crohn’s disease (CD), and its incidence has been reported to be as high as 17%-43%. Therapeutic strategies for fistulizing CD involve both medical and surgical approaches that largely have unsatisfactory results.

Infliximab is the first drug confirmed by randomized controlled studies that can promote CD anal fistula closure. However, only 36% of the patients in the treatment group showed fistula closure at the 54th week. It remains controversial whether we should use surgery, drugs, or surgery combined with drug therapy to treat CD anal fistulas. The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and long-term outcome of infliximab combined with surgery to treat perianal fistulizing CD.

Preliminary clinical studies showed that infliximab (IFX) combined with surgery was better than surgery or IFX alone. Treatment programs for anal fistulas in CD should combine drug therapy with surgical treatment. This study confirmed that IFX combined with surgery for treating CD anal fistulas had significant effects, improved the clinical cure rate, shortened the fistula healing time, and was associated with long-term better outcomes.

Our findings indicate that IFX combined with surgical treatment is a reasonable treatment approach for anal fistulas in CD.

Infliximab is a murine chimeric monoclonal antibody against tumor necrosis factor-α. It is the first Food and Drug Administration approved biological drug for treating CD, and it is also the first drug confirmed by randomized controlled studies that can promote CD anal fistula closure and sustain resolved symptoms for up to one year.

The manuscript deals with an interesting issue in coloproctology. Although the series is small, it is a prospective one, and describes in details all the patient work and outcome.

| 2. | Sands BE, Anderson FH, Bernstein CN, Chey WY, Feagan BG, Fedorak RN, Kamm MA, Korzenik JR, Lashner BA, Onken JE. Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:876-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1581] [Cited by in RCA: 1589] [Article Influence: 72.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ardizzone S, Porro GB. Perianal Crohn’s disease: overview. Dig Liver Dis. 2007;39:957-958. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chung W, Kazemi P, Ko D, Sun C, Brown CJ, Raval M, Phang T. Anal fistula plug and fibrin glue versus conventional treatment in repair of complex anal fistulas. Am J Surg. 2009;197:604-608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Caprilli R, Gassull MA, Escher JC, Moser G, Munkholm P, Forbes A, Hommes DW, Lochs H, Angelucci E, Cocco A. European evidence based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease: special situations. Gut. 2006;55 Suppl 1:i36-i58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 328] [Cited by in RCA: 276] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Schwartz DA, Pemberton JH, Sandborn WJ. Diagnosis and treatment of perianal fistulas in Crohn disease. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:906-918. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Orlando A, Colombo E, Kohn A, Biancone L, Rizzello F, Viscido A, Sostegni R, Benazzato L, Castiglione F, Papi C. Infliximab in the treatment of Crohn’s disease: predictors of response in an Italian multicentric open study. Dig Liver Dis. 2005;37:577-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | D’Haens GR, Panaccione R, Higgins PD, Vermeire S, Gassull M, Chowers Y, Hanauer SB, Herfarth H, Hommes DW, Kamm M. The London Position Statement of the World Congress of Gastroenterology on Biological Therapy for IBD with the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organization: when to start, when to stop, which drug to choose, and how to predict response? Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:199-212; quiz 213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 286] [Cited by in RCA: 302] [Article Influence: 20.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Regueiro M, Mardini H. Treatment of perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease with infliximab alone or as an adjunct to exam under anesthesia with seton placement. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2003;9:98-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 223] [Cited by in RCA: 210] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Topstad DR, Panaccione R, Heine JA, Johnson DR, MacLean AR, Buie WD. Combined seton placement, infliximab infusion, and maintenance immunosuppressives improve healing rate in fistulizing anorectal Crohn’s disease: a single center experience. Dis Colon Rectum. 2003;46:577-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gaertner WB, Decanini A, Mellgren A, Lowry AC, Goldberg SM, Madoff RD, Spencer MP. Does infliximab infusion impact results of operative treatment for Crohn’s perianal fistulas? Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1754-1760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sciaudone G, Di Stazio C, Limongelli P, Guadagni I, Pellino G, Riegler G, Coscione P, Selvaggi F. Treatment of complex perianal fistulas in Crohn disease: infliximab, surgery or combined approach. Can J Surg. 2010;53:299-304. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Best WR, Becktel JM, Singleton JW, Kern F. Development of a Crohn’s disease activity index. National Cooperative Crohn’s Disease Study. Gastroenterology. 1976;70:439-444. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Irvine EJ. Usual therapy improves perianal Crohn’s disease as measured by a new disease activity index. McMaster IBD Study Group. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1995;20:27-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | van Koperen PJ, Safiruddin F, Bemelman WA, Slors JF. Outcome of surgical treatment for fistula in ano in Crohn’s disease. Br J Surg. 2009;96:675-679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Poritz LS, Rowe WA, Koltun WA. Remicade does not abolish the need for surgery in fistulizing Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:771-775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Present DH, Rutgeerts P, Targan S, Hanauer SB, Mayer L, van Hogezand RA, Podolsky DK, Sands BE, Braakman T, DeWoody KL. Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1398-1405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1969] [Cited by in RCA: 1867] [Article Influence: 69.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ng SC, Plamondon S, Gupta A, Burling D, Swatton A, Vaizey CJ, Kamm MA. Prospective evaluation of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy guided by magnetic resonance imaging for Crohn’s perineal fistulas. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2973-2986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hyder SA, Travis SP, Jewell DP, McC Mortensen NJ, George BD. Fistulating anal Crohn’s disease: results of combined surgical and infliximab treatment. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:1837-1841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tanaka S, Matsuo K, Sasaki T, Nakano M, Sakai K, Beppu R, Yamashita Y, Maeda K, Aoyagi K. Clinical advantages of combined seton placement and infliximab maintenance therapy for perianal fistulizing Crohn’s disease: when and how were the seton drains removed? Hepatogastroenterology. 2010;57:3-7. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Hotokezaka M, Ikeda T, Uchiyama S, Tsuchiya K, Chijiiwa K. Results of seton drainage and infliximab infusion for complex anal Crohn’s disease. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011;58:1189-1192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Leombruno JP, Nguyen GC, Grootendorst P, Juurlink D, Einarson T. Hospitalization and surgical rates in patients with Crohn’s disease treated with infliximab: a matched analysis. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20:838-848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lémann M, Mary JY, Duclos B, Veyrac M, Dupas JL, Delchier JC, Laharie D, Moreau J, Cadiot G, Picon L. Infliximab plus azathioprine for steroid-dependent Crohn’s disease patients: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1054-1061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 278] [Cited by in RCA: 268] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lichtenstein GR, Yan S, Bala M, Blank M, Sands BE. Infliximab maintenance treatment reduces hospitalizations, surgeries, and procedures in fistulizing Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:862-869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 438] [Cited by in RCA: 431] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zabana Y, Domènech E, Mañosa M, Garcia-Planella E, Bernal I, Cabré E, Gassull MA. Infliximab safety profile and long-term applicability in inflammatory bowel disease: 9-year experience in clinical practice. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010;31:553-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Fidder H, Schnitzler F, Ferrante M, Noman M, Katsanos K, Segaert S, Henckaerts L, Van Assche G, Vermeire S, Rutgeerts P. Long-term safety of infliximab for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: a single-centre cohort study. Gut. 2009;58:501-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 320] [Cited by in RCA: 339] [Article Influence: 19.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Peyrin-Biroulet L, Reinisch W, Colombel JF, Mantzaris GJ, Kornbluth A, Diamond R, Rutgeerts P, Tang LK, Cornillie FJ, Sandborn WJ. Clinical disease activity, C-reactive protein normalisation and mucosal healing in Crohn’s disease in the SONIC trial. Gut. 2014;63:88-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 341] [Cited by in RCA: 390] [Article Influence: 32.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 28. | Zabana Y, Domènech E, San Román AL, Beltrán B, Cabriada JL, Saro C, Araméndiz R, Ginard D, Hinojosa J, Gisbert JP. Tuberculous chemoprophylaxis requirements and safety in inflammatory bowel disease patients prior to anti-TNF therapy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:1387-1391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lichtenstein GR, Feagan BG, Cohen RD, Salzberg BA, Diamond RH, Chen DM, Pritchard ML, Sandborn WJ. Serious infections and mortality in association with therapies for Crohn‘s disease: TREAT registry. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:621-630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 654] [Cited by in RCA: 640] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Abou-Zeid AA, Campos FG, Santoro GA S- Editor: Ma YJ L- Editor: Wang TQ E- Editor: Wang CH