Published online Mar 28, 2015. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i12.3741

Peer-review started: August 21, 2014

First decision: October 29, 2014

Revised: November 17, 2014

Accepted: December 20, 2014

Article in press: December 22, 2014

Published online: March 28, 2015

Processing time: 221 Days and 17.5 Hours

We report a case of phlegmonitis of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum in patient in an immunocompromised state. Culture of gastric juice and blood yielded Bacillus thuringiensis. This case showed that even low-virulence bacilli can cause lethal gastrointestinal phlegmonous gastritis in conditions of immunodeficiency.

Core tip: This is the first reported case of Bacillus thuringiensis as the suspected causative agent of rapidly progressive and fatal phlegmonitis of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum in patient in an immunocompromised state. Even low-virulence bacilli may be a causative pathogen of gastrointestinal phlegmonitis in patients in an immunocompromised state.

-

Citation: Matsumoto H, Ogura H, Seki M, Ohnishi M, Shimazu T. Fulminant phlegmonitis of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum due to

Bacillus thuringiensis . World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21(12): 3741-3745 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v21/i12/3741.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i12.3741

Phlegmonous gastritis is a rare acute and occasionally fatal bacterial infection of the gastric wall. Although a number of different bacterial organisms have been implicated as etiologic agents, Bacillus thuringiensis has not been reported as such an agent. We report a case of fatal phlegmonous gastritis with Bacillus thuringiensis suspected as the pathogen of intestinal infection. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported case of this type.

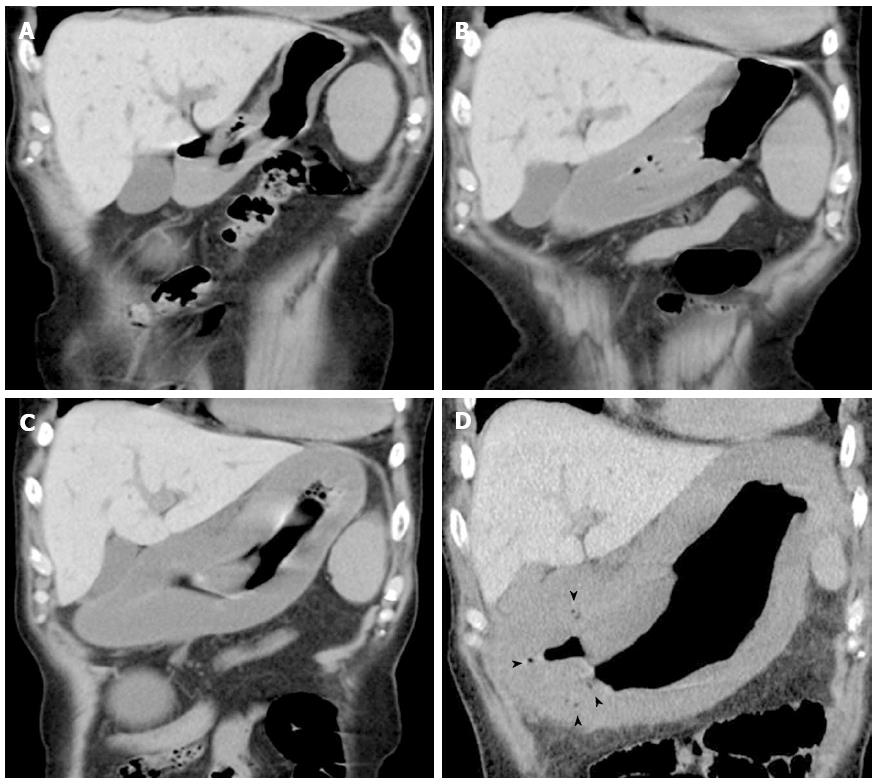

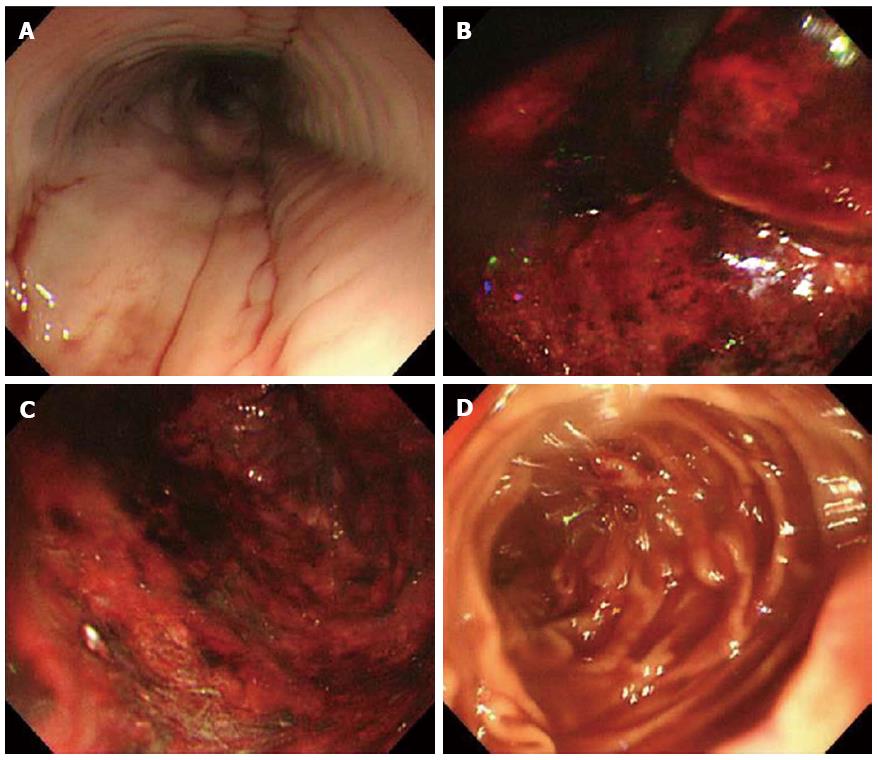

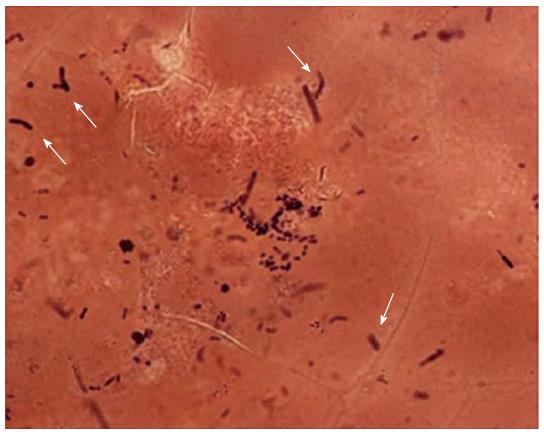

A 74-year-old man experiencing acute epigastric pain and nausea after a midnight meal was rushed to an emergency hospital 1 h after onset. He had past histories of myelofibrosis and stage III multiple myeloma[1]. He had neutropenia as a result of myelosuppressive chemotherapy, and on admission to hospital, his white blood count was 800 cells/mm3 with an absolute neutrophil count of 300 cells/mm3. Compared with a screening computed tomography (CT) scan performed 20 d before onset (Figure 1A), abdominal CT performed 4 h after onset revealed gastric wall hypertrophy (Figure 1B). Abdominal CT performed 6 h after onset showed continued significant spread of the wall hypertrophy to the total stomach (Figure 1C), and upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed ischemic change over the entire gastric mucosa. He was transferred to our critical care center 9 h after onset. On arrival, his temperature was 36.7°C, blood pressure was 98/69 mmHg, pulse rate was 113/min, and respiration rate was 36/min, indicating a shock state and systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Physical examination found local muscular guarding in the epigastric area. His blood chemistry data showed kidney and liver dysfunction, with a creatinine level of 2.6 mg/dL, alanine aminotransferase level of 77 IU/L, and aspartate aminotransferase level of 76 IU/L. Arterial blood gas analysis revealed severe acidosis, with a pH of 7.14 and blood lactate level of 117 mg/dL. Abdominal CT performed at 10 h after onset showed progression of wall hypertrophy to the lower esophagus and total stomach and duodenum and the presence of intramural gas (Figure 1D, arrowheads). Contrast enhancement of the gastric wall was very poor. Repeat upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed extensive ischemic change to the mucosa and necrosis extending from the lower esophagus to the stomach and duodenal bulb (Figure 2). A diagnosis of acute phlegmonitis of the esophagus, total stomach, and duodenum was made based on the CT images. Gram staining of the patient’s gastric juice revealed Gram-positive cocci and Gram-negative rods, and Gram-positive rods were also highlighted (Figure 3). We isolated Bacillus species in both blood and gastric juice cultures and genetically confirmed them to be Bacillus thuringiensis by sequencing of PCR amplified products of the groEL region and by detection of Bt toxins. Therefore, we diagnosed the patient as having acute phlegmonitis of the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum due to Bacillus thuringiensis (B. thuringiensis). MICs determined with an automated system (MicroScan WalkAway; Siemens, Munich, Germany) included gentamicin, < 2 μg/mL (susceptible); cefazolin, < 4 μg/mL (susceptible); ciprofloxacin, < 0.5 μg/mL (susceptible); and imipenem, < 1 μg/mL (susceptible).

Despite mechanical ventilation and treatment with meropenem (1 g × 3/d intravenously) and fluid and vasopressor therapy, the patient rapidly deteriorated due to septic disseminated intravascular coagulation and multiple organ failure. He died 14 h after arrival (24 h after disease onset).

Phlegmonous gastritis is caused by bacterial infection invading the gastric wall. Phlegmonitis of the stomach was initially recognized by Cruveilhier in the early 18th century[2]. Although the pathogenesis of acute phlegmonous gastritis is unclear, several mechanisms are implicated, such as direct invasion through areas of injury and by hematogenous or lymphatic spread. Immunosuppression, alcoholism, achlorhydria, and infection are also reported as predisposing factors[3]. We considered that myelofibrosis, multiple myeloma, and neutropenia resulting from chemotherapy might have been involved in disease development as predisposing factors for our patient’s immunocompromised status.

Phlegmonous gastritis may involve either a portion of the stomach (localized form) or the entire stomach (diffuse form). Phlegmonous involvement of the esophagus or duodenum beyond the stomach is extremely rare. To our knowledge, only 2 cases of phlegmonous involvement of segments of both the esophagus and duodenum beyond the stomach have been reported[4,5].

Patients usually present with an acute abdomen and septicemia[6], and rebound tenderness or muscle guarding can be observed in advanced cases[7]. Other symptoms include nausea, vomiting, and prostration. CT findings also provide supporting evidence for the diagnosis[8]. In the present patient, we could clearly detect for the first time, to our knowledge, the time-dependent changes of the spread of fulminant phlegmonitis on screening CT scans. Thus, CT was useful in the early diagnosis of this patient’s phlegmonous gastritis.

Submucosal involvement is the most prominent histopathologic finding in phlegmonous gastritis. Snare biopsy specimens are generally more useful for diagnosis because the submucosa is included[9], but if transmural purulent infection is present in advanced cases, diagnosis may be made by culture of gastric juice, other organs, and blood, as in our patient[10].

Although primarily caused by β-hemolytic group A Streptococcus, phlegmonous gastritis can be caused by many other bacterial organisms[11]. B. thuringiensis, a naturally occurring organism commonly found in soil, has been used for almost half a century as a specific pesticide against various insects[12]. To our knowledge, there are no other published reports of intestinal infection by B. thuringiensis.

Overall, the reported mortality rate for patients with phlegmonous gastritis with medically treated localized disease is 17%, whereas that for diffuse disease is 60%[6]. Treatment resistance and rapid disease progression were reported to be associated with high mortality[7]. The factors common to all of the survivors were early recognition and the prompt application of antibiotic treatment or surgery[13].

In summary, in a patient with rapidly progressive and fatal phlegmonitis spreading to the esophagus, total stomach, and duodenum, B. thuringiensis was identified genetically from cultures of gastric juice and blood and was considered the causative pathogen. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of B. thuringiensis relevant to intestinal infection. Even low-virulence bacilli may be a causative pathogen of gastrointestinal phlegmonitis in patients in an immunocompromised state.

A 74-year-old man with a history of myelofibrosis and stage III multiple myeloma presented with acute epigastric pain and nausea.

Local muscular guarding in the epigastric area.

Gastric perforation.

White blood count was 800 cells/mm3 with an absolute neutrophil count of 300 cells/mm3, blood chemistry data showed kidney and liver dysfunction, with a creatinine level of 2.6 mg/dL, alanine aminotransferase level of 77 IU/L, and aspartate aminotransferase level of 76 IU/L, and arterial blood gas analysis revealed severe acidosis, with a pH of 7.14 and blood lactate level of 117 mg/dL.

Abdominal computed tomography showed progression of gastric wall hypertrophy to the lower esophagus and total stomach and duodenum and the presence of intramural gas.

The authors isolated Bacillus species in both blood and gastric juice cultures and confirmed Bacillus thuringiensis (B. thuringiensis) by sequencing of PCR amplified products of the groEL region and by detection of B. thuringiensis toxins.

The patient was treated with mechanical ventilation and meropenem (1 g × 3/d intravenously) and fluid and vasopressor therapy.

Phlegmonous gastritis is caused by bacterial infection invading the gastric wall. Many bacterial organisms such as Staphylococcus spp. have been implicated as etiologic agents. Immunosuppression, alcoholism, achlorhydria, and infection are reported as predisposing factors. Phlegmonous involvement of the esophagus or duodenum beyond the stomach is extremely rare.

GroEL, one member of the heat shock protein family, which is highly conserved and essential to Bacillus, and its gene are used for detection and differentiation of cells belonging to the Bacillus spp. group. B. thuringiensis toxins are proteins produced by a bacterium that is lethal to insects.

The authors demonstrated for the first time data relevant to intestinal infection by B. thuringiensis. The data suggest that B. thuringiensis may have been one of the causes of the lethal pathological condition that occurred in a patient in an immunocompromised state.

B. thuringiensis was a relatively mild pathogen in the blood of this patient. Based on the previous history of this individual, the immunosuppressive status of the patient is a good reason to explain the fatal outcome caused by a relatively mild pathogen.

| 1. | Durie BG, Salmon SE. A clinical staging system for multiple myeloma. Correlation of measured myeloma cell mass with presenting clinical features, response to treatment, and survival. Cancer. 1975;36:842-854. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cruveilhier J. Traite d’anatomie pathologique generale, vol. 4. Paris: Masson et Cie 1862; 485. |

| 3. | Yun CH, Cheng SM, Sheu CI, Huang JK. Acute phlegmonous esophagitis: an unusual case (2005: 8b). Eur Radiol. 2005;15:2380-2381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yu T, Sekiguchi Y, Nakamura K, Tsuzawa T. Emphysematous esophago-gastro-duodenitis successfully treated by conservative therapy. Gastroenterological Endoscopy. 2005;47:978-985. |

| 5. | Nagami H, Tanaka T, Yano S. A case of acute phlegmonitis of the esophagus, total stomach and duodenum. Gastroenterology. 2008;46:601-606. |

| 6. | Kim HS, Hwang JH, Hong SS, Chang WH, Kim HJ, Chang YW, Kwon KH, Choi DL. Acute diffuse phlegmonous esophagogastritis: a case report. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25:1532-1535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Park CW, Kim A, Cha SW, Jung SH, Yang HW, Lee YJ, Lee HIe, Kim SH, Kim YH. A case of phlegmonous gastritis associated with marked gastric distension. Gut Liver. 2010;4:415-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sood BP, Kalra N, Suri S. CT features of acute phlegmonous gastritis. Clin Imaging. 2000;24:287-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bron BA, Deyhle P, Pelloni S, Krejs GJ, Siebenmann RE, Blum AL. Phlegmonous gastritis diagnosed by endoscopic snare biopsy. Am J Dig Dis. 1977;22:729-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Schultz MJ, van der Hulst RW, Tytgat GN. Acute phlegmonous gastritis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:80-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yu QQ, Tariq A, Unger SW, Cabello-Inchausti B, Robinson MJ. Phlegmonous gastritis associated with Kaposi sarcoma: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:801-803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sanahuja G, Banakar R, Twyman RM, Capell T, Christou P. Bacillus thuringiensis: a century of research, development and commercial applications. Plant Biotechnol J. 2011;9:283-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 615] [Cited by in RCA: 454] [Article Influence: 30.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kim GY, Ward J, Henessey B, Peji J, Godell C, Desta H, Arlin S, Tzagournis J, Thomas F. Phlegmonous gastritis: case report and review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:168-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Lukashevich IS S- Editor: Yu J L- Editor: A E- Editor: Zhang DN