Published online Nov 21, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i43.6315

Revised: August 17, 2012

Accepted: August 26, 2012

Published online: November 21, 2012

AIM: To evaluate whether antecolic reconstruction for duodenojejunostomy (DJ) can decrease delayed gastric emptying (DGE) rate after pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (PPPD) through literature review and meta-analysis.

METHODS: Articles published between January 1991 and April 2012 comparing antecolic and retrocolic reconstruction for DJ after PPPD were retrieved from the databases of MEDLINE (PubMed), EMBASE, OVID and Cochrane Library Central. The primary outcome of interest was DGE. Either fixed effects model or random effects model was used to assess the pooled effect based on the heterogeneity.

RESULTS: Five articles were identified for inclusion: two randomized controlled trials and three non-randomized controlled trials. The meta-analysis revealed that antecolic reconstruction for DJ after PPPD was associated with a statistically significant decrease in the incidence of DGE [odds ratio (OR), 0.06; 95% CI, 0.02-0.17; P < 0.00 001] and intra-operative blood loss [mean difference (MD), -317.68; 95% CI, -416.67 to -218.70; P < 0.00 001]. There was no significant difference between the groups of antecolic and retrocolic reconstruction in operative time (MD, 25.23; 95% CI, -14.37 to 64.83; P = 0.21), postoperative mortality, overall morbidity (OR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.20-1.46; P = 0.22) and length of postoperative hospital stay (MD, -9.08; 95% CI, -21.28 to 3.11; P = 0.14).

CONCLUSION: Antecolic reconstruction for DJ can decrease the DGE rate after PPPD.

- Citation: Su AP, Cao SS, Zhang Y, Zhang ZD, Hu WM, Tian BL. Does antecolic reconstruction for duodenojejunostomy improve delayed gastric emptying after pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy? A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(43): 6315-6323

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i43/6315.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i43.6315

Pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (PPPD), which preserves the whole stomach and 2.5 cm of duodenum[1], is generally accepted as a standard modality for periampullary malignancies. Compared with the classical pancreaticoduodenectomy (PD), PPPD was reported to have many advantages: (1) easier to perform; (2) less operative time and blood loss; and (3) better improvement of quality of life, nutritional status and weight gain[2-5]. However, despite the improvements in surgical techniques and postoperative management, PPPD has been associated with a higher delayed gastric emptying (DGE) rate than classical PD[6,7], although controversies still exist[8,9]. DGE, with an incidence ranging from 33% to 44%, is reported to be the major complication after PPPD[10-12]. Although not a lethal complication, DGE is often responsible for prolonged hospital stay and increased associated morbidity and hospital costs. Several studies revealed that DGE was closely related to the reconstruction technique[13,14]. Therefore, various modifications of reconstruction technique have been advocated to decrease the incidence of DGE.

A recently reported modification in the PPPD procedure is the performance of antecolic duodenojejunostomy (DJ) instead of retrocolic one. It has been found that antecolic reconstruction for DJ could significantly decrease the DGE rate after PPPD[15-19]. The reported DGE rate was > 30% for retrocolic reconstruction whereas it was < 15% for the antecolic reconstruction[19]. Nevertheless, two randomized controlled trials (RCTs) demonstrated that antecolic reconstruction was not superior to retrocolic reconstruction for DJ with respect to DGE after PPPD[20,21]. Up to date, the use of antecolic reconstruction for DJ to decrease the incidence of DGE after PPPD remains a topic of debate.

The primary objective of this study is to analyze the existing evidence regarding the antecolic and retrocolic reconstruction for DJ after PPPD in a systematic review and to perform a meta-analysis of operative outcomes, postoperative mortality, morbidity and length of postoperative hospital stay. The primary outcome of interest was DGE.

Multiple databases, including MEDLINE (PubMed), EMBASE, OVID, and Cochrane Library Central, were searched for RCTs or non-RCTs (N-RCTs) that evaluated antecolic vs retrocolic reconstruction for DJ after PPPD from January 1991 to April 2012. The following Mesh search headings were used: pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy, duodenojejunostomy, delayed gastric emptying, gastrostasis, antecolic reconstruction and retrocolic reconstruction. Citations were limited to those published on humans and in English language. A search was also performed for reference lists of the retrieved relevant articles for additional trials.

All included studies should fulfill the following criteria: (1) reporting the indication of PPPD; (2) comparing the results of antecolic and retrocolic reconstruction for DJ after PPPD; (3) reporting the incidence of DGE and other complications; and (4) when two or multiple studies were published by the same institution and/or authors, either one of the higher quality or the most recent article was included in the meta-analysis. Abstracts, case reports, letters, commentary, reviews without original data, studies lacking control groups or appropriate data for extraction and the number of patients less than 35 were excluded.

Two authors (Cao SS and Zhang Y) independently screened the title and abstract of each publication for potentially eligible studies. Then full articles of eligible trials were obtained for detailed evaluation. Any disagreement in the selection process was resolved through discussion by the two authors. If the two authors could not reach an agreement, a third person (Tian BL) would make a final decision on the eligibility of the study.

Two authors (Cao SS and Zhang Y) independently extracted data from all eligible studies, and then cross-checked the data. Data extracted from each study included: first author, study period, study design, inclusion and exclusion criteria, participant characteristics, interventions used, technique of reconstruction, morbidity and mortality rates, definition of DGE, DGE rate, and length of postoperative hospital stay. Any disagreements were resolved using the same method as mentioned above.

Jadad scoring system, which evaluates studies based on appropriate randomization, proper blinding, and an adequate description of withdrawals and dropouts, was used to assess the quality of RCTs[22]. The N-RCTs were scored on the following basis: prospective vs retrospective data collection; assignment to antecolic route or retrocolic route by means other than surgeon preference; and an explicit definition of DGE (studies were given a score of 1 for each of these areas; score 1-4)[23]. The study was considered to be of high quality if the quality score is ≥ 3.

Meta-analysis was performed in accordance with the recommendations of the Cochrane Collaboration. The effect outcomes estimated were odds ratio (OR) for dichotomous variables and mean difference (MD) for continuous variables, both reported with 95% CI. OR was defined as the odds of an adverse event occurring in the antecolic group (AG) vs the retrocolic group (RG) and it was considered statistically significant at P < 0.05 if the 95% CI did not cross the value 1. MD represented the difference between the two groups in the continuous variables and it was considered statistically significant at P < 0.05 if the 95% CI did not cross the value 0. Heterogeneity between studies was measured using χ2 and I2, and I2 > 50% was considered statistically significant. Either fixed effects model or random effects model was applied to calculate the pooled effect based on the heterogeneity. But random effects model was used first to assess the heterogeneity. Subgroups were used for sensitivity analysis and a funnel plot was used to identify publication bias.

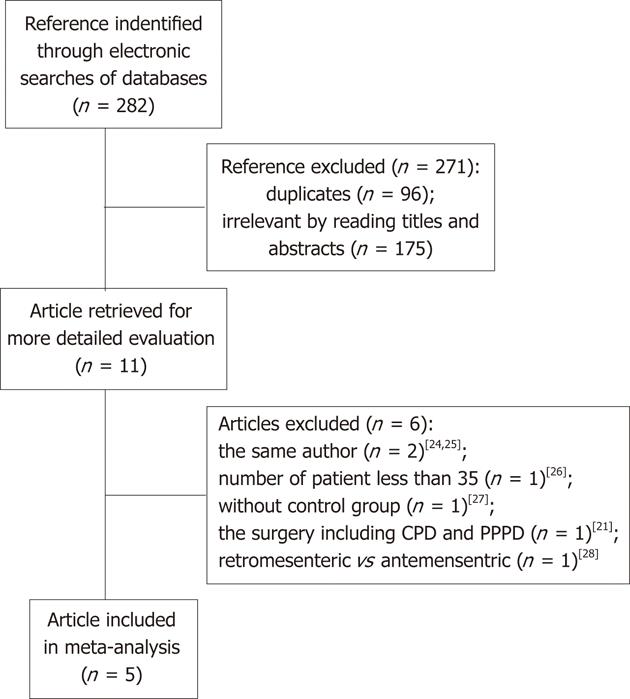

The literature searching strategy identified five articles[16-20] that met the inclusion criteria: two RCTs and three N-RCTs (Figure 1). The five studies involved a total of 451 patients: 240 in the AG and 211 in the RG. The details of the included studies are summarized in Table 1. The sample size ranged from 35 to 200 patients. The mean age of the patients varied between 61 and 70 years. The mean proportion of males varied between 41% and 67% and the proportion of malignancy varied between 63% and 100%. There were no significant differences between the two groups in age (MD, 1.50; 95% CI, -1.67 to 4.66; P = 0.35), sex (OR, 0.91; 95% CI, 0.62-1.32; P = 0.61) and the proportion of malignancy (OR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.49-1.16; P = 0.20). Of the five studies, only one reported the length of follow-up[19]. Surgical reconstruction and the definition of DGE are described in Table 2. In three studies[18-20], the description of reconstruction method revealed adequate consistency. There was some variation in the postoperative management, including the indication for nasogastric tube (NGT) removal, and administration of somatostatin analogues (SSA), antacid and prokinetic agents (PA).

| Ref. | Country | Study period | Design | Group | Patients | M/F | Mean age (yr) | Etiology of malignancy | Quality score |

| Kurosaki et al[16] | Japan | 1996-2002 | N-RCT | AG | 25 | 13/12 | 651 | 25 (100) | 1 |

| RG | 19 | 10/9 | 611 | 17 (89.5) | |||||

| Hartel et al[18] | Germany | 1996-2003 | N-RCT | AG | 100 | 41/59 | 61 (53-71)2 | 70 (70) | 2 |

| RG | 100 | 46/54 | 65 (53-74)2 | 75 (75) | |||||

| Murakami et al[17] | Japan | 1994-2006 | N-RCT | AG | 78 | 46/32 | 67 ± 11 | 49 (62.8) | 2 |

| RG | 20 | 10/10 | 66.7 ± 12.2 | 16 (80) | |||||

| Tani et al[19] | Japan | 2002-2004 | RCT | AG | 20 | 11/9 | 63.1 ± 9.21 | 16 (80) | 3 |

| RG | 54 | 36/18 | 64 ± 12 | 39 (72.2) | |||||

| Chijiiwa et al[20] | Japan | 2005-2007 | RCT | AG | 17 | 11/6 | 69.7 ± 11.0 | 12 (70.6) | 2 |

| RG | 18 | 9/9 | 66.9 ± 12.9 | 16 (88.9) |

| Ref. | Group | Reconstruction | Definition of DGE | Indication for removing NGT | SSA | Antacid | PA | ||

| Kurosaki et al[16] | AG | II | E-T-S PJ | E-T-S DJ | (1) NGT ≥ POD 10; (2) reinsertion of NGT | Aspiration < 200 mL/d | NM | NM | NM |

| RG | I | E-T-S PJ or PG | E-T-E DJ | ||||||

| Hartel et al[18] | AG | II | E-T-S PG | E-T-S DJ | (1) NGT ≥ POD 10; (2) inability to tolerate a solid diet ≤ POD 14 | Aspiration < 500 mL/d | No | H2 blocker | NM |

| RG | I | E-T-E DJ | |||||||

| Murakami et al[17] | AG | II | E-T-S PJ | E-T-S DJ | (1) NGT ≥ POD 10; (2) inability to tolerate regular diet ≤ POD 10; (3) vomiting ≥ 3 consecutive days after POD 5; (4) radiographic passage with water-soluble contrast medium revealing a holdup of the contrast medium in the stomach | (1) After tracheal extubation; (2) Aspiration of reintubation < 200 mL/d | Yes | PPI | Yes |

| RG | |||||||||

| Tani et al[19] | AG | II | E-T-S PJ | E-T-S DJ | (1) aspiration > 500 mL/d from NGT left ≥POD 10; (2) reinsertion of NGT; (3) failure of unlimited oral intake by POD 14 | Aspiration < 500 mL/d | No | H2 blocker | No |

| RG | |||||||||

| Chijiiwa et al[20] | AG | II | E-T-S PJ | E-T-S DJ | (1) NGT ≥ POD 10; (2) reinsertion of NGT; (3) inability to tolerate an appropriate amount solid food ≤ POD 14 | NM | NM | H2 blocker | No |

| RG | |||||||||

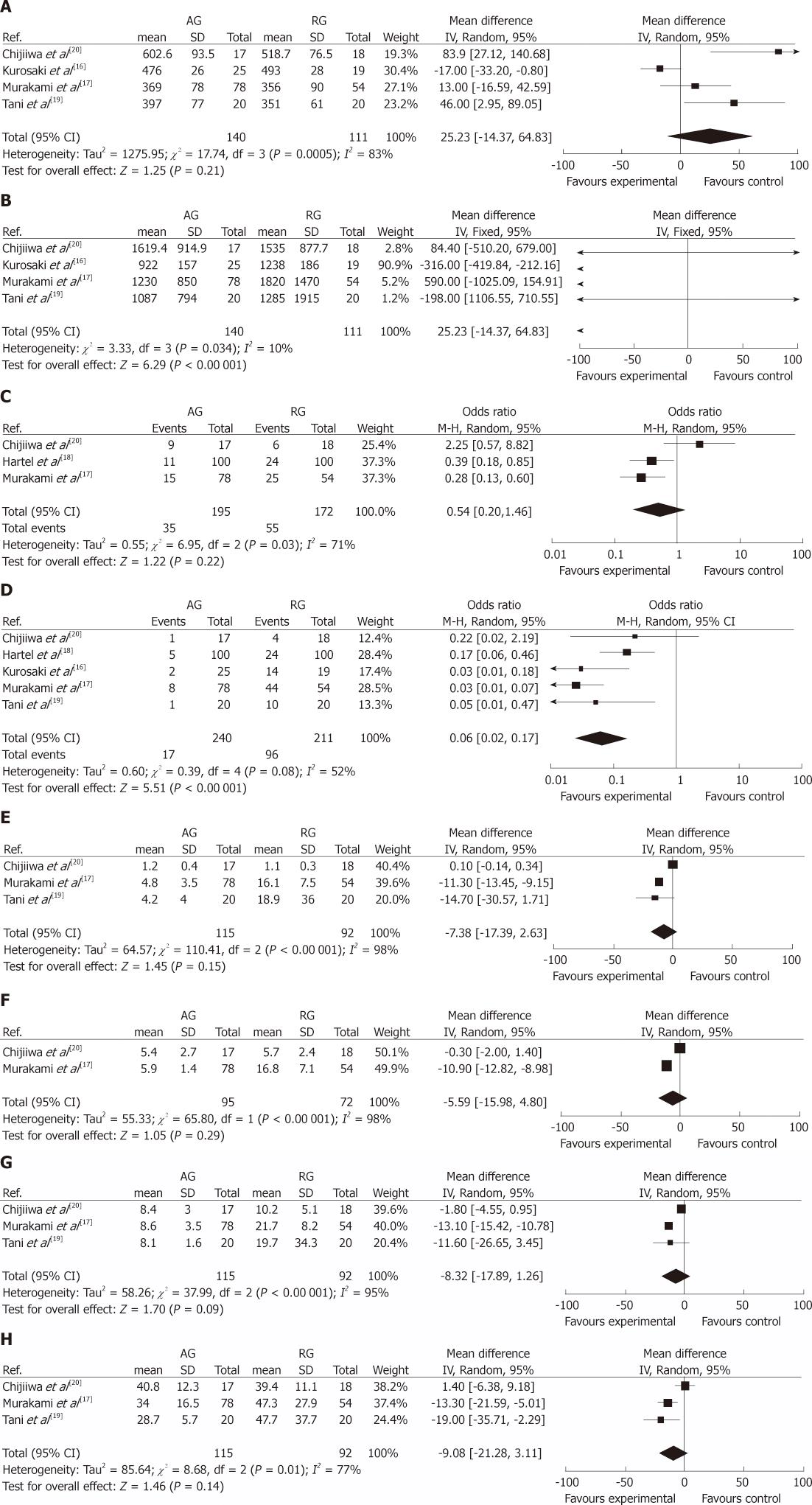

Operation time (min): Four studies[16,17,19,20] provided information regarding operation time. The random effects model was used because of significant heterogeneity (I2 = 83%) between studies, and the result of pooled analysis showed no statistically significant difference between the two groups (MD, 25.23; 95% CI, -14.37 to 64.83; P = 0.21) (Figure 2A).

Intra-operative blood loss (mL): Four studies[16,17,19,20] reported on intra-operative blood loss. It was significantly lower in the AG than in the RG (MD, -317.68; 95% CI, -416.67 to -218.70; P < 0.00 001) (Figure 2B).

Mortality: All the five studies reported on hospital mortality. Among the 451 patients involved, only one patient reported by Tani et al[19] died from acute hemorrhagic shock because of a Dieulafoy’s type ulcer in the RG. Therefore, there was no difference in mortality between the two groups.

Morbidity: Three studies[17,18,20], including 367 patients, were analyzed for the overall postoperative morbidity. No statistically significant difference was found between the two groups: 17.9% (AG) vs 32.0% (RG) (OR, 0.54; 95% CI, 0.20-1.46; P = 0.22). But there was statistically significant heterogeneity between the groups in the three studies (I2 = 71%) (Figure 2C). All studies provided data on DGE rate and pancreatic fistula (PF) rate. The summarized effect of DGE with random effects model (I2 = 52%) revealed a statistically significant result favoring AG with a DGE incidence of 7.1% (17/240) compared with a DGE rate of 45.5% (96/211) in the RG (OR, 0.06; 95% CI, 0.02-0.17; P < 0.00 001) (Figure 2D). However, the difference of the occurrence of PF between the two groups was not statistically significant. Concerning other postoperative complications, there was no significant difference between AG and RG in hemorrhage, intra-abdominal abscesses, bile leakage, the anastomotic leakage, wound infection and reoperation (Table 3).

| Complications | Number of studies | Number of patients | OR | 95% CI | P value | Heterogeneity (I2) | |

| AG | RG | ||||||

| Pancreatic fistula | 5[14-17,19] | 10/240 | 8/211 | 1.00 | 0.40, 2.50 | 0.99 | 0% |

| Hemorrhage | 4[14,16,17,19] | 3/162 | 5/157 | 0.63 | 0.18, 2.29 | 0.49 | 0% |

| Intra-abdominal abscesses | 4[14,16,17,19] | 11/162 | 14/157 | 0.72 | 0.30, 1.72 | 0.46 | 0% |

| Bile leakage | 3[14,17,19] | 0/62 | 2/57 | 0.28 | 0.03, 2.77 | 0.27 | 0% |

| The anastomotic leakage | 3[16,17,19] | 0/137 | 2/138 | 0.2 | 0.01, 4.14 | 0.29 | _ |

| Wound infection | 3[14,17,19] | 5/62 | 4/57 | 1.21 | 0.31, 4.72 | 0.78 | 0% |

| Reoperation | 3[14,16,17] | 2/145 | 6/139 | 0.33 | 0.07, 1.48 | 0.15 | 0% |

Postoperative time to remove NGT (d): Time for postoperative removal of NGT was reported in four studies[16,17,19,20], and three[17,19,20] studies reported the data using mean ± SD. No SD was reported by Kurosaki et al[16] (3 vs 14, P < 0.0001). The random effects model was used due to significant heterogeneity (I2 = 98%) between studies, and the overall effect indicated no difference between the AG and RG (MD, -7.38; 95% CI, -17.39 to 2.63; P = 0.15) (Figure 2E).

Postoperative time to start liquid meal (d): Three studies[16,17,20] evaluated postoperative time to start liquid meal, but one of them did not provide detailed information (8 vs 22, P < 0.0001)[16]. Meta-analysis of the remaining two studies with random effects model (I2 = 98%) showed no significant difference in the postoperative time to start liquid meal (MD, -5.59; 95% CI, -15.98 to 4.80; P = 0.29) (Figure 2F).

Postoperative time to start solid food (d): Four studies[16,17,19,20] reported the postoperative time to start solid food, but one of them did not provide sufficient information (14 vs 28, P < 0.0001)[16]. The summarized effect with random effects model (I2 = 95%) revealed no difference between the two groups (MD, -8.32; 95% CI, -17.89 to 1.26; P = 0.09) (Figure 2G).

Length of postoperative hospital stay (d): Data of length of postoperative hospital stay was available in four studies[17-20], but Hartel et al[18] did not report the SD (11.5 vs 17.5, P < 0.001). The other three studies showed no statistically significant difference between the two groups (MD, -9.08; 95% CI, -21.28 to 3.11; P = 0.14), which was associated with significant heterogeneity between the groups in all available studies for pooled analysis (I2 = 77%) (Figure 2H).

The following four subgroups were used for the sensitivity analysis: RCTs, N-RCTs, reconstruction with Billroth II in the AG and RG and reconstruction with Billroth II in AG and Billroth I in RG. The results of the analysis (Table 4), were the same as those when all studies were selected.

| Outcome | Number of studies | Number of patients | OR/MD | 95% CI | P value | Heterogeneity (I2) | |

| AG | RG | ||||||

| Randomized controlled trials | |||||||

| Delayed gastric emptying | 2[17,19] | 2/37 | 14/38 | 0.1 | 0.02, 0.47 | 0.004 | 0% |

| Mortality | 2[17,19] | 0/37 | 1/38 | 0.32 | 0.01, 8.26 | 0.49 | _ |

| Postoperative hospital stay (d) | 2[17,19] | 37 | 38 | -7.4 | -27.2, 12.40 | 0.46 | 79% |

| Non-randomized controlled trials | |||||||

| Morbidity | 2[15,16] | 26/178 | 49/154 | 0.33 | 0.19, 0.57 | < 0.00 001 | 0% |

| Delayed gastric emptying | 3[14,15,16] | 15/203 | 82/173 | 0.05 | 0.01, 0.20 | < 0.00 001 | 72% |

| Reconstruction with Billroth II in the two groups | |||||||

| Morbidity | 2[16,19] | 20/117 | 30/118 | 0.85 | 0.16, 4.69 | 0.86 | 79% |

| Delayed gastric emptying | 3[16,17,19] | 7/137 | 38/138 | 0.15 | 0.06, 0.34 | < 0.00 001 | 0% |

| Mortality | 3[16,17,19] | 0/137 | 1/138 | 0.32 | 0.01, 8.26 | 0.49 | _ |

| Postoperative hospital stay (d) | 2[17,19] | 37 | 38 | -7.4 | -27.2, 12.40 | 0.46 | 79% |

| Reconstruction with Billroth II in AG and Billroth I in RG | |||||||

| Delayed gastric emptying | 2[14,15] | 10/103 | 58/73 | 0.03 | 0.01, 0.06 | < 0.00 001 | 0% |

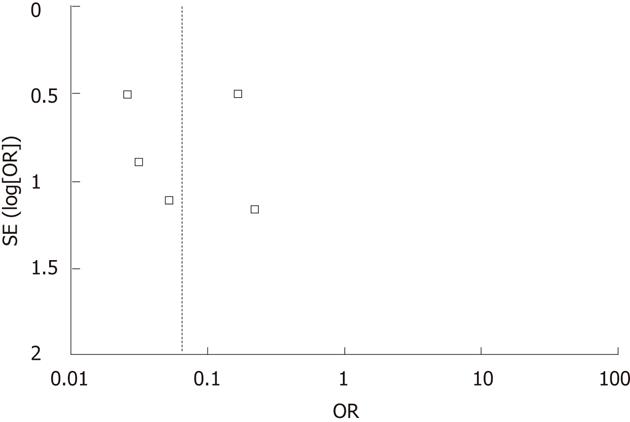

A funnel plot of all the studies reporting on DGE used in this meta-analysis is shown in Figure 3. There was no strong evidence of publication bias because all the studies were equally distributed around the vertical axis.

This meta-analysis found that antecolic reconstruction for DJ during PPPD was associated with a statistically significant decrease in the incidence of DGE and intra-operative blood loss. But antecolic reconstruction was not superior to retrocolic reconstruction with respect to operation time, postoperative mortality, overall morbidity, postoperative time to remove NGT and start liquid meal and solid food, and length of postoperative hospital stay.

Although DGE is the most frequent postoperative complication after PPPD, the true mechanism has not been fully clarified. A number of theories, including local ischemia of the antrum, low plasma motilin concentrations, gastric atony, transient pancreatitis, and gastric dysrhythmias, have been postulated to explain the occurrence of DGE after PPPD[29]. Moreover, DGE is always associated with angulation or torsion of the DJ in the early postoperative period[30].

Compared with retrocolic reconstruction, antecolic reconstruction may have several theoretical advantages. Antecolic reconstruction is believed to be less prone to torsion or angulation, causing DGE by mechanical obstruction[18,31]. In the antecolic reconstruction, the DJ anastomosis is located further away from pancreaticojejunostomy compared with the retrocolic reconstruction, which reduces the negative effect on antroduodenal motility by a small pancreatic anastomotic leak or a transient mild postoperative pancreatitis[18]. Furthermore, the descending jejunal loop is more mobile after antecolic reconstruction than after retrocolic reconstruction because of a minor degree of venous congestion and bowel edema[28].

DGE due to postoperative complications has been an accepted concept in the literature[31,32]. However, in the current study, the postoperative complications, including PF, hemorrhage, intra-abdominal abscesses, bile leakage, the anastomotic leakage, wound infection and reoperation, were similar in both groups. The lack of generally accepted definitions of postoperative complications may influence the results. Perhaps the significant higher intro-abdominal blood loss during surgery in the retrocolic reconstruction group may contribute to a risk for DGE.

DGE not only leads to repeated episodes of nausea and vomiting which prolongs NGT intubation and delays food intake, but also has an impact on duration of hospitalization[33]. Nevertheless, this meta-analysis demonstrated that antecolic reconstruction did not seem to offer an advantage with respect to postoperative time to remove NGT and start liquid meal and solid food, and length of postoperative hospital stay. This may result from a small number of studies providing insufficient information for analysis. Kurosaki et al[16] reported that postoperative time to remove NGT and start liquid meal and solid food were significantly shortened in antecolic reconstruction group. Hartel et al[18] also found that the median postoperative stay was significantly shorter in the antecolic reconstruction group than in the retrocolic reconstruction group. But neither of the studies reported the SD, which would greatly influence these pooled results.

The three types of reconstructions, including Billroth I, Billroth II and Roux-en Y, are frequently performed for digestive tract reconstruction after PPPD. Of the five studies included in the current meta-analysis, three studies applied Billroth II reconstruction for both groups[18-20] and pooled analysis showed a significantly decreased DGE rate in the antecolic reconstruction group. One study showed that Billroth II reconstruction with antecolic DJ achieved a significantly lower incidence of DGE than Billroth I reconstruction with retrocolic DJ[16]. Another research showed that DGE rate was significantly lowered with antecolic Roux-en Y reconstruction. However, according to the description and schematic illustration of the reconstruction method, the reconstruction method used should be the antecolic Billroth II reconstruction, but not the Roux-en Y reconstruction[17]. These data suggest that antecolic Billroth II reconstruction for DJ could be a useful method after PPPD to decrease the occurrence of DGE.

The present study has some limitations and the results should be interpreted with caution. First, this meta-analysis included a small number of studies and patients. Second, some low-quality studies were incorporated, and 60% of the data came from N-RCTs. Third, a test for heterogeneity was significant for most outcomes analyzed. The differences between the studies have led to heterogeneity, including differences in the type of digestive tract reconstruction, definition of DGE and postoperative management. In order to reduce the heterogeneity, subgroup analysis was performed and the results were the same as those when all studies were selected, which further confirmed the conclusion drawn above.

In conclusion, the current study suggests that antecolic reconstruction for DJ can decrease DGE rate after PPPD. However, further standardized RCTs with general type of digestive tract reconstruction and definition of DGE are urgently needed to draw a definitive conclusion.

Various modifications of reconstruction technique have been advocated to decrease delayed gastric emptying (DGE) rate after pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (PPPD). A recently reported modification is the performance of antecolic duodenojejunostomy (DJ) instead of retrocolic approach. Up to now, however, the selection of antecolic or retrocolic reconstruction for DJ remains an issue of debate. In this paper, therefore, a systematic review and meta-analysis were performed to evaluate whether antecolic reconstruction for DJ can decrease DGE rate after PPPD.

DGE is reported to be the leading complication after PPPD. Although not a lethal complication, DGE is often responsible for prolonged hospital stay and increased associated morbidity and hospital costs. In the area of decreasing DGE rate with different reconstructions for DJ, the research hotspot is to evaluate the effect of antecolic and retrocolic reconstruction for DJ on the incidence of DGE after PPPD.

This review suggests that antecolic reconstruction for DJ can decrease DGE rate after PPPD. According to the authors, this is the first systematic review using the meta-analysis to study the benefit of antecolic reconstruction for DJ in decreasing the DGE rate after PPPD.

The study result that antecolic reconstruction for DJ can decrease DGE rate after PPPD could guide the selection of the reconstruction route for DJ.

This is a technically good study of antecolic vs retrocolic reconstruction for DJ after PPPD. The results are interesting and suggest that antecolic reconstruction for DJ can decrease DGE rate after PPPD.

| 1. | Traverso LW, Longmire WP. Preservation of the pylorus in pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1978;146:959-962. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Klinkenbijl JH, van der Schelling GP, Hop WC, van Pel R, Bruining HA, Jeekel J. The advantages of pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy in malignant disease of the pancreas and periampullary region. Ann Surg. 1992;216:142-145. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Diener MK, Knaebel HP, Heukaufer C, Antes G, Büchler MW, Seiler CM. A systematic review and meta-analysis of pylorus-preserving versus classical pancreaticoduodenectomy for surgical treatment of periampullary and pancreatic carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2007;245:187-200. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Zerbi A, Balzano G, Patuzzo R, Calori G, Braga M, Di Carlo V. Comparison between pylorus-preserving and Whipple pancreatoduodenectomy. Br J Surg. 1995;82:975-979. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Mosca F, Giulianotti PC, Balestracci T, Di Candio G, Pietrabissa A, Sbrana F, Rossi G. Long-term survival in pancreatic cancer: pylorus-preserving versus Whipple pancreatoduodenectomy. Surgery. 1997;122:553-566. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Ohwada S, Ogawa T, Kawate S, Tanahashi Y, Iwazaki S, Tomizawa N, Yamada T, Ohya T, Morishita Y. Results of duct-to-mucosa pancreaticojejunostomy for pancreaticoduodenectomy Billroth I type reconstruction in 100 consecutive patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;193:29-35. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Shan YS, Tsai ML, Chiu NT, Lin PW. Reconsideration of delayed gastric emptying in pancreaticoduodenectomy. World J Surg. 2005;29:873-89; discussion 880. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Seiler CA, Wagner M, Bachmann T, Redaelli CA, Schmied B, Uhl W, Friess H, Büchler MW. Randomized clinical trial of pylorus-preserving duodenopancreatectomy versus classical Whipple resection-long term results. Br J Surg. 2005;92:547-556. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Tran KT, Smeenk HG, van Eijck CH, Kazemier G, Hop WC, Greve JW, Terpstra OT, Zijlstra JA, Klinkert P, Jeekel H. Pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy versus standard Whipple procedure: a prospective, randomized, multicenter analysis of 170 patients with pancreatic and periampullary tumors. Ann Surg. 2004;240:738-745. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Akizuki E, Kimura Y, Nobuoka T, Imamura M, Nagayama M, Sonoda T, Hirata K. Reconsideration of postoperative oral intake tolerance after pancreaticoduodenectomy: prospective consecutive analysis of delayed gastric emptying according to the ISGPS definition and the amount of dietary intake. Ann Surg. 2009;249:986-994. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Park JS, Hwang HK, Kim JK, Cho SI, Yoon DS, Lee WJ, Chi HS. Clinical validation and risk factors for delayed gastric emptying based on the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) Classification. Surgery. 2009;146:882-887. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Welsch T, Borm M, Degrate L, Hinz U, Büchler MW, Wente MN. Evaluation of the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery definition of delayed gastric emptying after pancreatoduodenectomy in a high-volume centre. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1043-1050. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Bassi C, Falconi M, Molinari E, Salvia R, Butturini G, Sartori N, Mantovani W, Pederzoli P. Reconstruction by pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy following pancreatectomy: results of a comparative study. Ann Surg. 2005;242:767-71, discussion 771-3. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Kimura F, Suwa T, Sugiura T, Shinoda T, Miyazaki M, Itoh H. Sepsis delays gastric emptying following pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2002;49:585-588. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Horstmann O, Becker H, Post S, Nustede R. Is delayed gastric emptying following pancreaticoduodenectomy related to pylorus preservation? Langenbecks Arch Surg. 1999;384:354-359. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Kurosaki I, Hatakeyama K. Clinical and surgical factors influencing delayed gastric emptying after pyloric-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52:143-148. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Murakami Y, Uemura K, Sudo T, Hayashidani Y, Hashimoto Y, Nakagawa N, Ohge H, Sueda T. An antecolic Roux-en Y type reconstruction decreased delayed gastric emptying after pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:1081-1086. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Hartel M, Wente MN, Hinz U, Kleeff J, Wagner M, Müller MW, Friess H, Büchler MW. Effect of antecolic reconstruction on delayed gastric emptying after the pylorus-preserving Whipple procedure. Arch Surg. 2005;140:1094-1099. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Tani M, Terasawa H, Kawai M, Ina S, Hirono S, Uchiyama K, Yamaue H. Improvement of delayed gastric emptying in pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy: results of a prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2006;243:316-320. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Chijiiwa K, Imamura N, Ohuchida J, Hiyoshi M, Nagano M, Otani K, Kai M, Kondo K. Prospective randomized controlled study of gastric emptying assessed by (13)C-acetate breath test after pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy: comparison between antecolic and vertical retrocolic duodenojejunostomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16:49-55. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Gangavatiker R, Pal S, Javed A, Dash NR, Sahni P, Chattopadhyay TK. Effect of antecolic or retrocolic reconstruction of the gastro/duodenojejunostomy on delayed gastric emptying after pancreaticoduodenectomy: a randomized controlled trial. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:843-852. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1-12. [PubMed] |

| 23. | McKay A, Mackenzie S, Sutherland FR, Bathe OF, Doig C, Dort J, Vollmer CM, Dixon E. Meta-analysis of pancreaticojejunostomy versus pancreaticogastrostomy reconstruction after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br J Surg. 2006;93:929-936. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Chijiiwa K, Ohuchida J, Hiyoshi M, Nagano M, Kai M, Kondo K. Vertical retrocolic duodenojejunostomy decreases delayed gastric emptying after pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54:1874-1877. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Murakami H, Yasue M. A vertical stomach reconstruction after pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy. Am J Surg. 2001;181:149-152. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Ueno T, Takashima M, Iida M, Yoshida S, Suzuki N, Oka M. Improvement of early delayed gastric emptying in patients with Billroth I type of reconstruction after pylorus preserving pancreatoduodenectomy. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2009;16:300-304. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Riediger H, Makowiec F, Schareck WD, Hopt UT, Adam U. Delayed gastric emptying after pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy is strongly related to other postoperative complications. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:758-765. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Park YC, Kim SW, Jang JY, Ahn YJ, Park YH. Factors influencing delayed gastric emptying after pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:859-865. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Paraskevas KI, Avgerinos C, Manes C, Lytras D, Dervenis C. Delayed gastric emptying is associated with pylorus-preserving but not classical Whipple pancreaticoduodenectomy: a review of the literature and critical reappraisal of the implicated pathomechanism. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:5951-5958. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Ueno T, Tanaka A, Hamanaka Y, Tsurumi M, Suzuki T. A proposal mechanism of early delayed gastric emptying after pylorus preserving pancreatoduodenectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 1995;42:269-274. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Horstmann O, Markus PM, Ghadimi MB, Becker H. Pylorus preservation has no impact on delayed gastric emptying after pancreatic head resection. Pancreas. 2004;28:69-74. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Yeo CJ, Cameron JL, Sohn TA, Coleman J, Sauter PK, Hruban RH, Pitt HA, Lillemoe KD. Pancreaticoduodenectomy with or without extended retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy for periampullary adenocarcinoma: comparison of morbidity and mortality and short-term outcome. Ann Surg. 1999;229:613-622; discussion 622-624. [PubMed] |

Peer reviewers: Yoshiharu Motoo, MD, PhD, FACP, FACG, Professor, Chairman, Department of Medical Oncology, Kanazawa Medical University,1-1 Daigaku, Uchinada, Ishikawa 920-0293, Japan; George Sgourakis, MD, PhD, FACS, 2nd Surgical Department and Surgical Oncology Unit, Red Cross Hospital, 11 Mantzarou Str, Neo Psychiko, Athens, 15451, Greece

S- Editor Shi ZF L- Editor A E- Editor Xiong L