Published online Nov 7, 2012. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i41.5957

Revised: May 2, 2012

Accepted: May 5, 2012

Published online: November 7, 2012

AIM: To investigate the usefulness of a new rendezvous technique for placing stents using the Kumpe (KMP) catheter in angulated or twisted biliary strictures.

METHODS: The rendezvous technique was performed in patients with a biliary stricture after living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) who required the exchange of percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage catheters for inside stents. The rendezvous technique was performed using a guidewire in 19 patients (guidewire group) and using a KMP catheter in another 19 (KMP catheter group). We compared the two groups retrospectively.

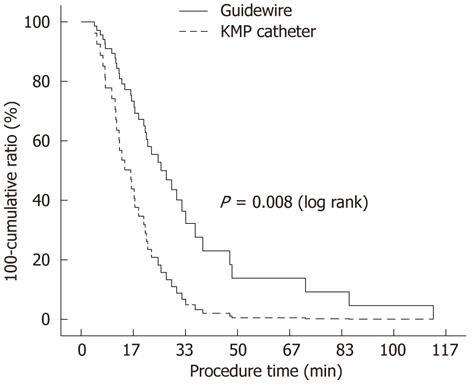

RESULTS: The baseline characteristics did not differ between the groups. The success rate for placing inside stents was 100% in both groups. A KMP catheter was easier to manipulate than a guidewire. The mean procedure time in the KMP catheter group (1012 s, range: 301-2006 s) was shorter than that in the guidewire group (2037 s, range: 251-6758 s, P = 0.022). The cumulative probabilities corresponding to the procedure time of the two groups were significantly different (P = 0.008). The factors related to procedure time were the rendezvous technique method, the number of inside stents, the operator, and balloon dilation of the stricture (P < 0.05). In a multivariate analysis, the rendezvous technique method was the only significant factor related to procedure time (P = 0.010). The procedural complications observed included one case of mild acute pancreatitis and one case of acute cholangitis in the guidewire group, and two cases of mild acute pancreatitis in the KMP catheter group.

CONCLUSION: The rendezvous technique involving use of the KMP catheter was a fast and safe method for placing inside stents in patients with LDLT biliary stricture that represents a viable alternative to the guidewire rendezvous technique.

- Citation: Chang JH, Lee IS, Chun HJ, Choi JY, Yoon SK, Kim DG, You YK, Choi MG, Han SW. Comparative study of rendezvous techniques in post-liver transplant biliary stricture. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18(41): 5957-5964

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v18/i41/5957.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v18.i41.5957

Biliary strictures develop in approximately 30% of patients after living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) and 50%-70% of biliary strictures can be treated by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)[1,2]. However, percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) is recommended for patients in whom ERCP has failed[3]. Because of complications associated with the use of PTBD catheters such as pain, leakage, or infection, replacing PTBD catheters with inside stents by ERCP is required in many patients with PTBD catheters. When an angulated or twisted biliary stricture interrupts passage of a guidewire over the stricture, it is difficult to replace the PTBD catheter with inside stents by ERCP[1,4,5]. The rendezvous technique can be used to overcome this difficulty.

The rendezvous procedure combines the endoscopic technique with percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC) to facilitate cannulation of the bile duct in cases where previous endoscopic attempts have failed[6-9]. This combined technique increases the success rate of biliary tract cannulation and facilitates the diagnosis and treatment of biliary tract disorders[10-12]. We previously reported that the rendezvous technique allows for successful placement of inside stents in angulated or twisted biliary strictures after LDLT[13]. In the classic rendezvous technique, a guidewire is used for an endoscopic approach to the bile duct. However, manipulation of the guidewire is difficult and somewhat cumbersome, and kinking or breakage of the guidewire can occur[14]. The modified rendezvous technique involves pushing the guidewire from the common bile duct into inside the lumen of an ERCP cannula outside the ampulla in the duodenum[14]. It is also often difficult to push the guidewire inside the lumen of the ERCP cannula.

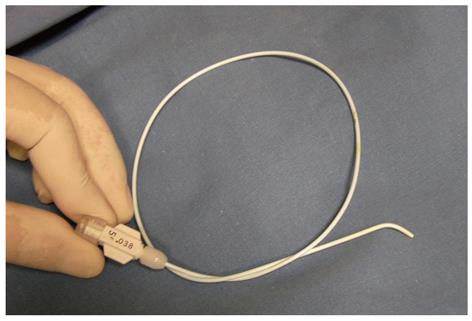

We attempted to resolve these problems by using a Kumpe (KMP) catheter (5F, 40 cm, Cook, Bloomington, IN, United States; Figure 1) instead of a guidewire. A KMP catheter is short enough for easy manipulation and also reduces the risk of contamination during the procedure. The end of a KMP catheter is slightly angulated and turning the end is simple, which allows the KMP catheter to approximate the ERCP cannula, end-to-end. Herein, we evaluated the usefulness and safety of the new modified rendezvous technique using a KMP catheter to place inside stents into biliary strictures after LDLT and compared it with the rendezvous technique performed using a guidewire.

Between November 2006 and June 2011, patients undergoing the rendezvous technique performed using a KMP catheter (n = 19) were compared retrospectively with those undergoing the rendezvous technique performed using a guidewire (n = 19) at a single institution. Abdominal computed tomography and magnetic resonance cholangiography revealed that patients had biliary strictures at the anastomotic site after LDLT. They had PTBD catheters that were intended to be exchanged with inside stents. The rendezvous procedure was performed, because their anastomotic strictures were too angulated or twisted to place inside stents by ERCP. The rendezvous technique was performed using a guidewire before 2010. We invented the rendezvous technique using a KMP catheter in 2010, and have subsequently performed it ever since. No patient was treated using both techniques. All patients undergoing the rendezvous technique were consecutively enrolled. Patient anonymity was preserved and the Institutional Review Board of Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital approved the study (KC11RISI0845). This study protocol was in complete compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki for medical research involving human subjects, as revised in Seoul in 2008.

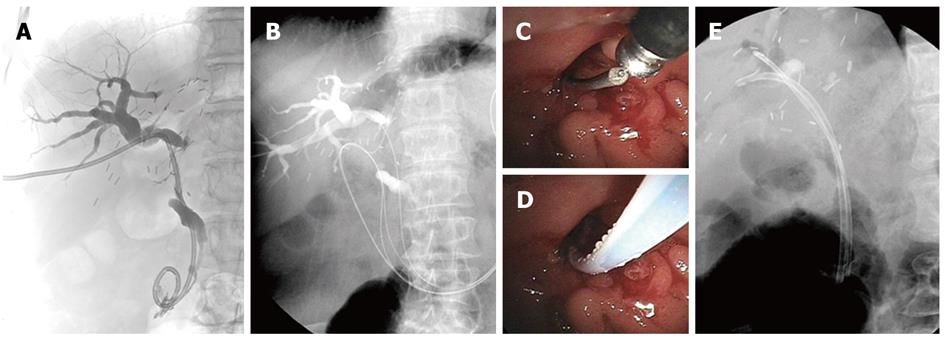

One or two PTBD catheters were passed over the stricture in all patients. After an overnight fast, patients were sedated using midazolam and pethidine in the supine position. PTC was performed by injecting contrast medium through the PTBD catheter (Figure 2A). A guidewire (0.035 inch Jagwire; Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, United States) was introduced along the PTBD catheter until it advanced over the major ampulla into the duodenum, which was followed by removing the PTBD catheter (Figure 2B). After the patients were moved into a prone position, ERCP was performed using a video duodenoscope (ED-450XT5; Fujinon, Saitama City, Saitama, Japan). The guidewire exited the papilla and was identified inside the duodenal lumen using a duodenoscope. A minor sphincterotomy was performed alongside the guidewire in cases where an endoscopic sphincterotomy had not been performed. A bottle-top metal-tip ERCP cannula (MTW Endoscopie, Wesel, Germany) was introduced through the accessory channel of the duodenoscope and placed in front of the end of the guidewire (Figure 2C). The bottle-top metal-tip ERCP cannula and the guidewire were manipulated cautiously to insert the end of the guidewire into the ERCP cannula, which minimized damage to the guidewire (Figure 2D). The guidewire was pushed through the ERCP cannula and the ERCP cannula was advanced along the percutaneously inserted guidewire over the biliary stricture. Then, the percutaneously inserted guidewire was progressively withdrawn while another endoscopically inserted guidewire was pushed through the ERCP cannula. If the guidewire was not pushed easily through the ERCP cannula, the guidewire passing through the ampulla was captured by a basket and then withdrawn through the endoscopic working channel[15]. After pulling the guidewire was completely out of the scope, the soft or floppy end of the guidewire was placed back into the ERCP cannula and advanced into the biliary tree. When a remaining stricture was suspected at the anastomotic site, balloon dilation of the anastomotic strictures was performed using a balloon catheter (6 or 8 mm in diameter; Hurricane RX; Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, United States). The inside stents were placed over the guidewire (Amsterdam-type biliary stents; 7F-11.5 F in diameter, 10-16 cm in length; Wilson-Cook Medical Winston-Salem, NC, United States, or Medi-Globe, Achenmuhle, Germany). The proximal side of the stent was located to cover the stricture, and the distal side of the stent passed 1-2 cm outside of the major papilla (Figure 2E). We intended to place the proximal end of the inside stent in the bile duct, not in the liver parenchyma, with assistance from fluoroscopic imaging. If we needed to insert another inside stent over the stricture, another guidewire was inserted retrogradely over the stricture site, and a second inside stent was placed along the second guidewire (Figure 2E). In cases where two guidewires had been inserted at different branches of the bile ducts along two PTBD tracts during PTC, two inside stents were placed along these guidewires.

The anastomotic angle between the common hepatic duct of the recipient and the right hepatic duct of the donor (confluence of the anterior and posterior branches) were measured. If a confluent duct was not obvious, we chose the intrahepatic duct (IHD) in which the PTBD catheter had been placed. After successful insertion of the stents, a follow-up ERCP was performed within 3-6 mo. During the follow-up ERCP, the stents placed previously were removed, and the degree of improvement in biliary stricture and IHD or common bile duct (CBD) stones was evaluated. Restenting was performed if the stricture remained.

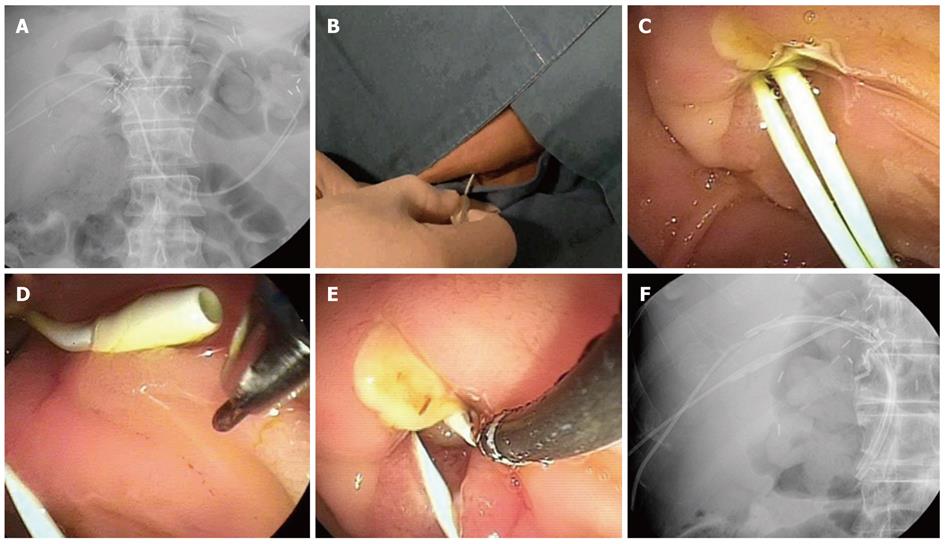

The basic PTC and ERCP techniques were the same as the guidewire technique. During PTC, a guidewire was introduced along the PTBD catheter until it advanced over the major ampulla into the duodenum, which was followed by removal of the PTBD catheter. The KMP catheter (5F, 40 cm) was placed along the guidewire, and then the guidewire was removed (Figure 3A). In cases where two PTBD catheters had been inserted at different branches of the bile ducts, two KMP catheters were placed along two PTBD tracts. ERCP was performed after the patients were moved into the prone position. The KMP catheter was pulled back until the end of the catheter was located near the major ampulla in the duodenum (Figure 3B, C). The KMP catheter was rotated to approximate the short angulated tip of the KMP catheter and the end of the ERCP cannula, and then the preloaded guidewire in the ERCP cannula was advanced through the KMP catheter (Figure 3D, E). The KMP catheter was pulled back proximal to the stricture for placement of inside stents. Inside stents were placed over the stricture by endoscopy as described in the guidewire technique (Figure 3F). When additional information about the recipient’s bile duct was required, a cholangiogram was performed by injecting contrast via the KMP catheter. The KMP catheter was removed after insertion of the inside stents.

Procedure time was defined as the time after positioning the end of the duodenoscope in front of the major ampulla until placement of the inside stents. A Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test was used to compare categorical data and Student’s t-test or the Mann-Whitney U-test was used for comparisons of continuous data to analyze differences between the groups. The cumulative probability curves corresponding to the procedure time for each rendezvous technique were determined using the Kaplan-Meier method, and these were compared using the log rank test. A multivariate analysis was performed with the significant factors identified from the univariate analysis using the Cox proportional hazard regression model (forward: conditional method). Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS software, version 14 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). P-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

The baseline characteristics of the patients are described in Table 1. No significant differences were observed be-tween the guidewire and KMP catheter groups. The mean duration between LDLT and the rendezvous procedure was 388 d (range: 31-2116 d), and the mean duration between PTBD and the rendezvous procedure was 154 d (range: 4-1526 d). Twenty-seven patients received one PTBD catheter, and 11 patients received two PTBD catheters. Laboratory findings showed normal or mildly elevated serum liver function tests, but no evidence of cholangitis.

| Guidewire group(n = 19) | KMP catheter group(n = 19) | P-value | |

| Mean age, yr (SD) | 51.3 (9.3) | 52.5 (10.2) | 0.619 |

| Male sex (%) | 13 (68) | 15 (79) | 0.714 |

| Pretransplantation liver disease (%) | 0.524 | ||

| End-stage liver cirrhosis | 5 (26) | 8 (42) | |

| Hepatitis B | 2 | 6 | |

| Hepatitis B and alcohol | 2 | 1 | |

| Cryptogenic | 1 | 1 | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 9 (47) | 6 (32) | |

| Hepatitis B | 9 | 5 | |

| Hepatitis C | 0 | 1 | |

| Fulminant hepatitis | 5 (26) | 5 (26) | |

| Hepatitis A | 1 | 2 | |

| Hepatitis B | 3 | 3 | |

| Unknown origin | 1 | 0 | |

| Mean duration between LDLT and rendezvous procedure, d (SD) | 338 (197) | 438 (516) | 0.704 |

| Mean duration between PTBD and rendezvous procedure, d (SD) | 91 (52) | 217 (351) | 0.511 |

| Mean anastomotic angle1, ° (SD) | 118 (15) | 125 (17) | 0.148 |

| Mean no. of PTBD catheters, (SD) | 1.4 (0.5) | 1.2 (0.4) | 0.517 |

| Mean diameter of PTBD catheter, F (SD) | 10.7 (2.8) | 9.1 (2.2) | 0.365 |

| Pre-laboratory findings2, mean (SD) | |||

| WBC (× 109/L) | 4.61 (1.80) | 4.87 (1.98) | 0.569 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.37 (0.90) | 1.60 (1.51) | 0.988 |

| Alanine aminotransaminase (IU/L) | 60.6 (41.6) | 90.2 (128) | 0.748 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | 332 (173) | 289 (175) | 0.649 |

| γ-glutamyl transferase (IU/L) | 248 (179) | 278 (203) | 0.800 |

| Rendezvous success rate (%) | 19 (100) | 19 (100) | 1.000 |

| No. of stents inserted, mean (SD) | 1.5 (0.5) | 1.5 (0.5) | 0.749 |

| Inside stent diameter (F), mean (SD) | 10.4 (2.7) | 9.8 (0.7) | 0.308 |

| CBD or IHD stones (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (11) | 0.152 |

| Stricture dilation (%) | 4 (21) | 0 (0) | 0.037 |

| Mean procedure time3, s (range) | 2037 (251-6758) | 1012 (301-2006) | 0.022 |

| Post-laboratory findings4, mean (SD) | |||

| White blood cell (× 109/L) | 5.19 (1.88) | 6.18 (2.34) | 0.215 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 2.15 (1.61) | 2.11 (1.51) | 0.942 |

| Alanine aminotransaminase (IU/L) | 85.1 (67.3) | 115 (136) | 0.953 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | 341 (167) | 312 (198) | 0.419 |

| γ-glutamyl transferase (IU/L) | 279 (189) | 368 (319) | 0.531 |

| Amylase (U/L) | 284 (585) | 207 (241) | 0.737 |

| Complications | 0.740 | ||

| Acute cholangitis | 1 | 0 | |

| Hyperamylasemia | 5 | 6 | |

| Acute pancreatitis | 1 | 2 | |

| Migration of stents | 1 | 0 |

Inside stents were successfully placed in all patients. Thus, the technical success rate in both groups was 100% (Table 1). No patient was treated with the KMP catheter technique after failure of the guidewire technique. In the guidewire group, the guidewire was pushed through the ERCP cannula and the ERCP cannula was advanced along the percutaneously inserted guidewire over the biliary stricture in 12 patients. In the remaining seven patients, the guidewire passing through the ampulla was captured by a basket and then withdrawn through the endoscopic working channel. IHD or CBD stones were identified in two patients in the KMP catheter group, and the stones were removed during the procedure. Dilation of the anastomotic stricture was performed in four patients in the guidewire group because of a tight stricture. We used the ERCP cannula preloaded with a guidewire in the KMP catheter group, and thus, it was not necessary to pull the guidewire back and reinsert it. It was easier to manipulate the KMP catheter than a guidewire. The procedure time was significantly shorter in the KMP group than in the guidewire group; the mean procedure time was 1012 s vs 2037 s, respectively (P = 0.022). In the cumulative probability curve corresponding to procedure time, the probability curves of the two rendezvous groups differed significantly according to the log rank test (P = 0.008, Figure 4), suggesting that the use of a KMP catheter was associated with a significantly shorter procedure time. Serum levels of liver enzymes were slightly elevated after the rendezvous procedure, but this was not clinically significant, and no differences were observed between the groups.

The factors related to procedure time were analyzed (Table 2). The method used for the rendezvous technique, the number of inside stents, the operator, and balloon dilation of the stricture were significant factors related to procedure time. The procedure times did not differ between the first and second half in each rendezvous group.

| Factors | n | Procedure time, s, mean (range) | P-value | |

| Rendezvous | Guidewire | 19 | 2037 (251-6758) | 0.022 |

| Technique | KMP catheter | 19 | 1012 (301-2006) | |

| IHD or CBD | Present | 2 | 1517 (1202-1831) | 0.513 |

| Stone | Absent | 36 | 1525 (251-6758) | |

| No. of inside stents | One | 19 | 1198 (251-5144) | 0.04 |

| Two | 19 | 1851 (666-6758) | ||

| Operator | Lee IS | 31 | 1292 (251-6758) | 0.024 |

| Chang JH | 7 | 2555 (735-5144) | ||

| Balloon dilation | Yes | 4 | 2568 (2189-2895) | 0.008 |

| of the stricture | No | 34 | 1402 (251-6758) | |

| Age | < 60 | 29 | 1571 (251-6758) | 0.904 |

| > 60 | 9 | 1373 (301-2895) | ||

| Procedure | First half2 | 15 | 1009 (368-1934) | 0.635 |

| Familiarity1 | Second half | 16 | 1557 (251-6758) |

Four significant factors in univariate analysis were evaluated for multivariate analysis. The number of inserted stents, operator, and balloon dilatation of the biliary stricture were not significant in the Cox proportional hazard regression model (P > 0.05). The rendezvous technique method was the only significant factor related to procedure time (P = 0.010, odds ratio 2.663, 95%CI 1.258-5.637, Table 3). Therefore, the rendezvous technique was an independent factor related to procedure time.

| Factors | P-value | Odds ratio (95%CI) |

| Rendezvous technique (guidewire vs rendezvous) | 0.010 | 2.663 (1.258-5.637) |

| No. of inside stents (1 vs 2) | 0.067 | |

| Operator (Lee IS vs Chang JH) | 0.195 | |

| Balloon dilation (yes vs no) | 0.289 |

Acute complications occurred in two patients after rendezvous procedures (10.5%) in each group. In the guidewire group, one case of acute cholangitis and one mild case of acute pancreatitis developed after the procedures. Acute cholangitis with fever and epigastric pain occurred due to the migration of an inside stent proximally, resulting in obstruction of the distal end of the stent. We removed the original inside stent and put a new one in its place. The patient ultimately recovered. The patient with acute pancreatitis had the longest procedure time in the guidewire group (112 min) and a sustained elevation into total serum bilirubin for 4 d after the procedure. During the procedure, guidewire manipulation was difficult because the two guidewires were tangled. Two mild cases of acute pancreatitis developed after the procedure in the KMP catheter group. Peak serum amylase levels were 873 U/L and 847 U/L, respectively. Their abdominal pain lasted for 2 d.

We followed the patients in the guidewire and KMP catheter groups for average of 40 mo (range: 12-57 mo) and 8 mo (range: 2-14 mo), respectively. Inside stents were exchanged a mean of 0.8 times (range: 0-4 times) until they were free of biliary stricture. Finally, 19 patients reached stent-free status (seven in the KMP catheter group and 12 in the guidewire group), and 14 patients (nine in the KMP catheter group and five in the guidewire group) still had inside stents. Four patients had plastic inside stents that had been replaced with covered metal stents to treat a biliary stricture. The attempt to change an inside stent by ERCP failed in one patient, and the patient required to undergo PTBD again. IHD or CBD stones developed in seven patients and a biliary cast developed in one patient; these were removed by ERCP. Two patients died during follow-up. One patient in the guidewire group died from recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma 14 mo after the rendezvous procedure, and another patient in the KMP catheter group died from a hepatic artery occlusion and hepatic failure 12 mo later.

The present study demonstrated that the rendezvous technique using a KMP catheter is easy, fast, and safe when used to place inside stents for a biliary stricture after LDLT and represents a viable alternative to the rendezvous technique performed using a guidewire. No significant complications were observed.

Patients in whom ERCP stent placement failed needed to undergo PTBD or surgical treatment[3,16,17]. Although maintaining a PTBD catheter for a long period is beneficial for treating biliary strictures[18-20], it may be difficult for patients due to the development of PTBD catheter-related complications, such as leakage, pain, infection, and accidental removal of the PTBD catheter[21,22]. The discomfort caused by carrying a PTBD catheter also reduces the patient’s quality of life and disturbs his or her daily routine. Hence, replacing PTBD catheters with inside stents is recommended. However, stenting using ERCP in patients with angulated or twisted biliary strictures is difficult and sometimes fails. Our previous study showed that the rendezvous technique is a useful alternative method for successful placement of inside stents in these patients[13]. A few cases of biliary complication after liver transplantation have supported the usefulness of the rendezvous technique for biliary strictures and stones or biliary leakage from bile duct anastomosis[23-25].

Although the rendezvous technique is useful and facilitates cannulation of the bile duct in cases where previous endoscopic attempts have failed[6-9], there were some drawbacks to the conventional version of the rendezvous technique. In the classic rendezvous technique, grasping the guidewire outside of the ampulla with a forcep or snare is occasionally difficult due to its slippery surface. Kinking or breakage of the guidewire can also occur while grabbing and pulling guidewires through the accessory channel of the duodenoscope. A long guidewire outside the skin of the PTBD tract is difficult to manipulate and increases the risk of contamination. Additionally, it is inconvenient to pull the guidewire back and place the soft or floppy end of the wire back into the ERCP cannula, and then advance it into the biliary tree to reduce liver damage from the stiff end of the guidewire. To reduce these shortcomings, a modified rendezvous technique was introduced so that the end of the guidewire is pushed inside the lumen of an ERCP cannula and the ERCP cannula is advanced along the wire into the CBD[14]. However, this technique also has its disadvantage. The guidewire is not easily pushed inside the ERCP cannula lumen, and this procedure is frequently time-consuming. A parallel cannulation technique using a sphincterotome in a retrograde fashion, alongside a biliary drainage catheter, can be useful for selective CBD cannulation[26]. However, parallel cannulation is not suitable for selective IHD cannulation.

A KMP catheter is useful for overcoming these drawbacks. The KMP catheter was introduced as a vascular catheter and has been widely used in the interventional radiology. A KMP catheter is as short as 40 cm, so the portion outside the skin from the PTBD tract is short enough for easy manipulation including to-and-fro motion and turning, which are used to move the curved distal end of the KMP catheter up-and-down and right-to-left and reduces the risk of contamination. Because the end of a KMP catheter is slightly angulated and turning the end is simple, end-to-end contact between the ends of an ERCP cannula and a KMP catheter is easy to achieve without the use of a sphincterotome. It is possible to insert a preloaded guidewire within the ERCP cannula into the KMP catheter retrogradely. Therefore, it is unnecessary to pull the guidewire back out of the duodenoscope and to reinsert the soft or floppy end of the wire first. When ERCP is delayed after placing a KMP catheter, the KMP catheter can be kept in place for a few hours until ERCP is performed, and it is impossible when using the guidewire technique. Even if two KMP catheters are placed along two previous PTBD tracts, the degree of discomfort is reduced due to the thin caliber of the KMP catheter, and two KMP catheters are not likely to tangle, in contrast to guidewires. Additionally, a cholangiogram can be performed by injecting contrast via the KMP catheter during ERCP, which provides additional information about the recipient’s bile duct. If the rendezvous procedure fails, reinserting a PTBD catheter is easy when a KMP catheter is in place. Recently a case report on the rendezvous technique with a C2 catheter which is similar to a KMP catheter, was introduced in a patient with gallbladder carcinoma and a metastatic right intrahepatic bile duct obstruction[27].

Because this study was retrospective and not randomized, there were some limitations. First, the time to perform the procedures differed between the two groups. The guidewire group procedures preceded those of the KMP catheter group. It is possible that our familiarity with each of the rendezvous procedures differed somewhat. However, the procedure times in chronological order in each rendezvous group did not differ significantly; moreover, those of the first and second half in each group were not different in the factor analysis. Second, we performed an analysis of the factors related to procedure time, but other factors affecting procedure time that were not analyzed in our study may have played a role. For example, the severity and condition of stricture differed somewhat among the patients. However, we supposed that these factors were minor and not significantly related to procedure time. The rendezvous technique itself can overcome the state of the stricture in difficult situation. Third, although we connected the 5F KMP catheter with the tip of the ERCP cannula by a guidewire without great difficulty, the wider diameter of the catheter might make it easier to connect the catheter and ERCP cannula. If a straight catheter is used, a sphincterotome will facilitate the insertion of a guidewire through the catheter.

In conclusion, the rendezvous technique performed with a KMP catheter is a fast and safe method for placing inside stents in biliary strictures in LDLT patients who need to exchange the PTBD catheter for inside stents and represents a viable alternative to the guidewire technique. The KMP catheter rendezvous technique is recommended for LDLT patients who have angulated or twisted anastomotic biliary strictures. We expect further comparative prospective studies with a larger cohort of patients to demonstrate the benefits of the KMP catheter technique in the future.

The rendezvous technique allows for the successful placement of inside stents in angulated or twisted biliary strictures after liver transplantation. In the classic rendezvous technique, a guidewire is used for the endoscopic approach to the bile duct. However, manipulation of the guidewire is difficult and somewhat cumbersome, and kinking or breakage of the guidewire can occur.

A Kumpe (KMP) catheter (5F, 40 cm) is useful for overcoming the drawbacks associated with the classic rendezvous technique. The KMP catheter is short enough for easy manipulation and it also reduces the risk of contamination during the procedure.

Because the end of a KMP catheter is shortly angulated and turning the end is simple, end-to-end contact between the ends of an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) cannula and a KMP catheter is easily achieved even without the use of a sphincterotome. It is possible to insert a preloaded guidewire within the ERCP cannula into the KMP catheter in retrograde fashion. The rendezvous technique involving use of the KMP catheter was a fast and safe method for placing inside stents in living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) biliary strictures and represents a viable alternative to use of the guidewire rendezvous technique.

The KMP catheter rendezvous technique is recommended for LDLT patients who have angulated or twisted anastomotic biliary strictures.

The authors demonstrated the usefulness of a new rendezvous technique for placing stents using a KMP catheter in angulated or twisted biliary strictures. The results are interesting and suggest that rendezvous technique involving use of the KMP catheter was a fast and safe method for placing inside stents in patients with LDLT biliary stricture that represents a viable alternative to the guidewire rendezvous technique.

| 1. | Yazumi S, Yoshimoto T, Hisatsune H, Hasegawa K, Kida M, Tada S, Uenoyama Y, Yamauchi J, Shio S, Kasahara M. Endoscopic treatment of biliary complications after right-lobe living-donor liver transplantation with duct-to-duct biliary anastomosis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2006;13:502-510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tashiro H, Itamoto T, Sasaki T, Ohdan H, Fudaba Y, Amano H, Fukuda S, Nakahara H, Ishiyama K, Ohshita A. Biliary complications after duct-to-duct biliary reconstruction in living-donor liver transplantation: causes and treatment. World J Surg. 2007;31:2222-2229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kim ES, Lee BJ, Won JY, Choi JY, Lee DK. Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage may serve as a successful rescue procedure in failed cases of endoscopic therapy for a post-living donor liver transplantation biliary stricture. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:38-46. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Tsujino T, Isayama H, Sugawara Y, Sasaki T, Kogure H, Nakai Y, Yamamoto N, Sasahira N, Yamashiki N, Tada M. Endoscopic management of biliary complications after adult living donor liver transplantation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2230-2236. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Sharma S, Gurakar A, Jabbour N. Biliary strictures following liver transplantation: past, present and preventive strategies. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:759-769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 263] [Cited by in RCA: 282] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 6. | Scapa E, Peer A, Witz E, Eshchar J. "Rendez-vous" procedure (RVP) for obstructive jaundice. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1994;4:82-85. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Ponchon T, Valette PJ, Bory R, Bret PM, Bretagnolle M, Chavaillon A. Evaluation of a combined percutaneous-endoscopic procedure for the treatment of choledocholithiasis and benign papillary stenosis. Endoscopy. 1987;19:164-166. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Martin DF. Combined percutaneous and endoscopic procedures for bile duct obstruction. Gut. 1994;35:1011-1012. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Dowsett JF, Vaira D, Hatfield AR, Cairns SR, Polydorou A, Frost R, Croker J, Cotton PB, Russell RC, Mason RR. Endoscopic biliary therapy using the combined percutaneous and endoscopic technique. Gastroenterology. 1989;96:1180-1186. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Passi RB, Rankin RN. The transhepatic approach to a failed endoscopic sphincterotomy. Gastrointest Endosc. 1986;32:221-225. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Chespak LW, Ring EJ, Shapiro HA, Gordon RL, Ostroff JW. Multidisciplinary approach to complex endoscopic biliary intervention. Radiology. 1989;170:995-997. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Calvo MM, Bujanda L, Heras I, Cabriada JL, Bernal A, Orive V, Miguelez J. The rendezvous technique for the treatment of choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:511-513. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Chang JH, Lee IS, Chun HJ, Choi JY, Yoon SK, Kim DG, You YK, Choi MG, Choi KY, Chung IS. Usefulness of the rendezvous technique for biliary stricture after adult right-lobe living-donor liver transplantation with duct-to-duct anastomosis. Gut Liver. 2010;4:68-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mönkemüller KE, Linder JD, Fry LC. Modified rendezvous technique for biliary cannulation. Endoscopy. 2002;34:936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Liu YD, Wang ZQ, Wang XD, Yang YS, Linghu EQ, Wang WF, Li W, Cai FC. Stent implantation through rendezvous technique of PTBD and ERCP: the treatment of obstructive jaundice. J Dig Dis. 2007;8:198-202. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Lee SH, Ryu JK, Woo SM, Park JK, Yoo JW, Kim YT, Yoon YB, Suh KS, Yi NJ, Lee JM. Optimal interventional treatment and long-term outcomes for biliary stricture after liver transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2008;22:484-493. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Sutcliffe R, Maguire D, Mróz A, Portmann B, O'Grady J, Bowles M, Muiesan P, Rela M, Heaton N. Bile duct strictures after adult liver transplantation: a role for biliary reconstructive surgery? Liver Transpl. 2004;10:928-934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Thuluvath PJ, Pfau PR, Kimmey MB, Ginsberg GG. Biliary complications after liver transplantation: the role of endoscopy. Endoscopy. 2005;37:857-863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Seo JK, Ryu JK, Lee SH, Park JK, Yang KY, Kim YT, Yoon YB, Lee HW, Yi NJ, Suh KS. Endoscopic treatment for biliary stricture after adult living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2009;15:369-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Morelli G, Fazel A, Judah J, Pan JJ, Forsmark C, Draganov P. Rapid-sequence endoscopic management of posttransplant anastomotic biliary strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:879-885. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Weber A, Gaa J, Rosca B, Born P, Neu B, Schmid RM, Prinz C. Complications of percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage in patients with dilated and nondilated intrahepatic bile ducts. Eur J Radiol. 2009;72:412-417. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Mueller PR, van Sonnenberg E, Ferrucci JT. Percutaneous biliary drainage: technical and catheter-related problems in 200 procedures. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1982;138:17-23. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Miraglia R, Traina M, Maruzzelli L, Caruso S, Di Pisa M, Gruttadauria S, Luca A, Gridelli B. Usefulness of the "rendezvous" technique in living related right liver donors with postoperative biliary leakage from bile duct anastomosis. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2008;31:999-1002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Aytekin C, Boyvat F, Yimaz U, Harman A, Haberal M. Use of the rendezvous technique in the treatment of biliary anastomotic disruption in a liver transplant recipient. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:1423-1426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Di Pisa M, Traina M, Miraglia R, Maruzzelli L, Volpes R, Piazza S, Luca A, Gridelli B. A case of biliary stones and anastomotic biliary stricture after liver transplant treated with the rendez-vous technique and electrokinetic lithotritor. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:2920-2923. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Dickey W. Parallel cannulation technique at ERCP rendezvous. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:686-687. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Lee TH, Park SH, Lee SH, Lee CK, Lee SH, Chung IK, Kim HS, Kim SJ. Modified rendezvous intrahepatic bile duct cannulation technique to pass a PTBD catheter in ERCP. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:5388-5390. [PubMed] |

Peer reviewers: Takahiro Nakazawa, Professor, Nagoya City University, Shinmichi1-11-11 Nishiku, Nagoya 451-0043, Japan; Jin Hong Kim, Professor, Department of Gastroenterology, Ajou University Hospital, San 5, Wonchon-dong, Yeongtong-gu, Suwon 442-721, South Korea

S- Editor Gou SX L- Editor A E- Editor Zhang DN