Published online Dec 21, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i47.6010

Revised: June 10, 2010

Accepted: June 17, 2010

Published online: December 21, 2010

AIM: To investigate two distinct clinical phenotypes of reflux esophagitis and intra-hernial ulcer (Cameron lesions) in patients with large hiatal hernias.

METHODS: A case series study was performed with 16 831 patients who underwent diagnostic esophagogastroduodenoscopy for 2 years at an academic referral center. A hiatus diameter ≥ 4 cm was defined as a large hernia. A sharp fold that surrounded the cardia was designated as an intact gastroesophageal flap valve (GEFV), and a loose fold or disappearance of the fold was classified as an impaired GEFV. We studied the associations between large hiatal hernias and the distinct clinical phenotypes (reflux esophagitis and Cameron lesions), and analyzed factors that distinguished the clinical phenotypes.

RESULTS: Large hiatal hernias were found in 49 (0.3%) of 16 831 patients. Cameron lesions and reflux esophagitis were observed in 10% and 47% of these patients, and 0% and 8% of the patients without large hiatal hernias, which indicated significant associations between large hiatal hernias and these diseases. However, there was no coincidence of the two distinct disorders. Univariate analysis demonstrated significant associations between Cameron lesions and the clinico-endoscopic factors such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) intake (80% in Cameron lesion cases vs 18% in non-Cameron lesion cases, P = 0.015) and intact GEFV (100% in Cameron lesion cases vs 18% in non-Cameron lesion cases, P = 0.0007). In contrast, reflux esophagitis was linked with impaired GEFV (44% in reflux esophagitis cases vs 8% in non-reflux esophagitis cases, P = 0.01). Multivariate regression analysis confirmed these significant associations.

CONCLUSION: GEFV status and NSAID intake distinguish clinical phenotypes of large hiatal hernias. Cameron lesions are associated with intact GEFV and NSAID intake.

- Citation: Kaneyama H, Kaise M, Arakawa H, Arai Y, Kanazawa K, Tajiri H. Gastroesophageal flap valve status distinguishes clinical phenotypes of large hiatal hernia. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(47): 6010-6015

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i47/6010.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i47.6010

Hiatal hernia promotes gastric acid access to the esophagus and impairs its clearance. The overall consequence of increased esophageal acid exposure is reflux esophagitis. Larger hiatal hernias impair the normal anti-reflux mechanisms to a greater extent than do smaller hernias. Esophagitis severity and esophageal acid exposure increase significantly for hernias > 3 cm in length, as measured endoscopically[1]. The size of a hiatal hernia and the degree of lower sphincter hypotension are the most significant independent predictors of esophagitis presence and severity[2].

Gastric erosions or ulcers located on or near the neck of a large hiatal hernia sac, collectively referred to as Cameron lesions, cause gastrointestinal bleeding and anemia[3]. The prevalence of Cameron lesions is known to be dependent upon hiatal hernia size, with higher prevalence corresponding to larger hiatal hernia size[4].

There is convincing evidence that large hiatal hernias involve each of the two distinct disorders reflux esophagitis and Cameron lesions. However, the relationships between large hiatal hernias and these two disorders have not been clarified. We aimed to elucidate these relationships and to clarify the key factors that differentiate the clinical phenotypes of large hiatal hernias into reflux esophagitis and/or Cameron lesions.

From January 2005 to January 2007, 16 831 patients were referred for diagnostic esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) to the Department of Endoscopy at Jikei University Hospital. Patients with the diagnosis of hiatal hernia were identified using databases of endoscopic and medical records. Endoscopic images of these patients were retrieved from the endoscopic filing system (Olympus Medical Systems, Tokyo, Japan), to confirm the presence of Cameron lesions and/or reflux esophagitis, as well as the presence and size of the hiatal hernia.

Cameron lesions were defined as gastric erosions or ulcers located on or near the neck of the hiatal hernia sac. Although Cameron lesions were originally described as linear erosions[3], various lesion shapes, namely, linear, oblong or round, have been reported[4]. Therefore, the shapes of the erosions or ulcers were not taken into account as long as the lesions were located on or near the neck of the hiatal hernia sac. Long linear erosions that extended from the neck to the lower or middle gastric body were excluded from this definition.

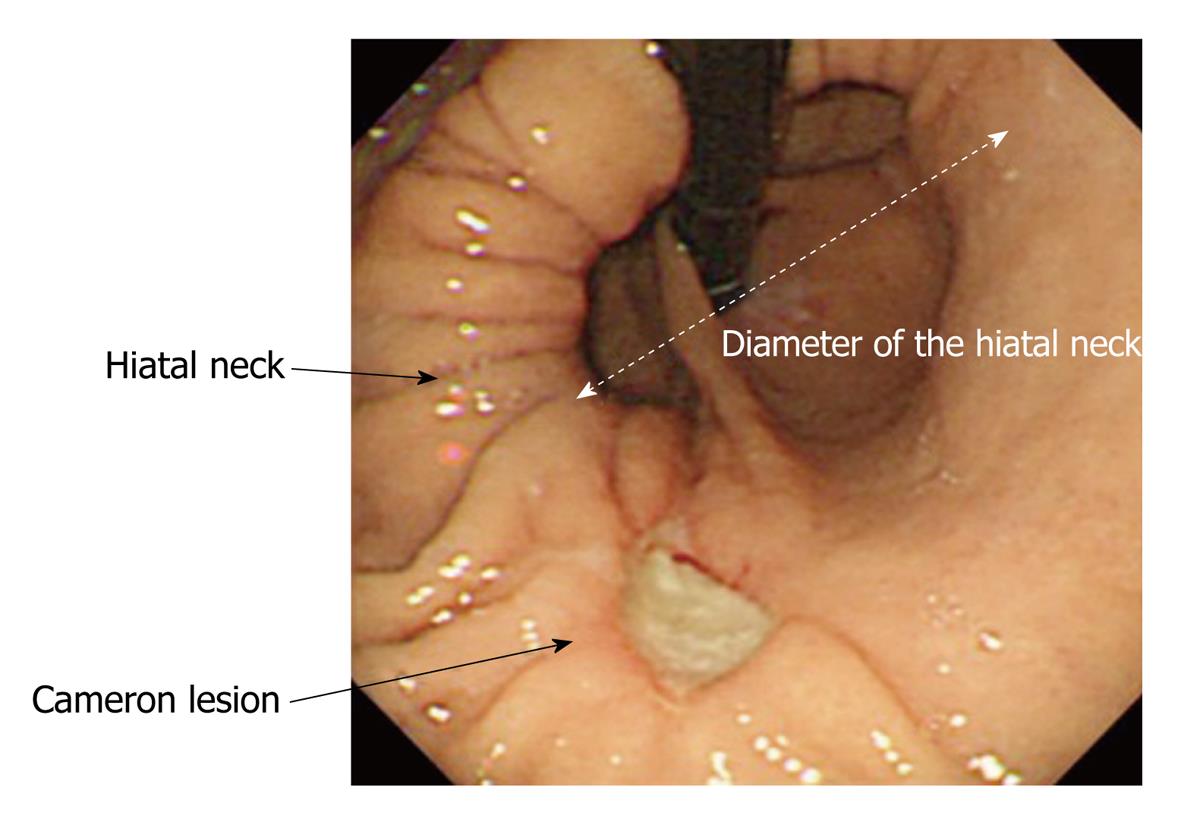

The standard endoscopic recording of diagnostic EGD comprised 40 still images, including two images of the gastric cardia from the retroflex views of the so-called U-turn and J-turn, and two images of the esophagogastric junction from the esophageal antegrade view. Additional still images were obtained with no limitation as to image numbers when abnormal findings, such as esophagitis and ulceration, were noted. Hiatal hernia size was defined as the diameter of the neck of the hernia sac in the still images of the retroflex views of the gastric cardia. For example, if the diameter of the neck was three times that of the endoscope shaft (the diameters of the endoscopes used ranged from 8.9 mm to 10.4 mm; GIF-Q260, GIF-XQ260, GIF-H260, GIF-Q240, GIF-XQ240; Olympus Medical Systems), the size of the hiatal hernia was recorded as 3 cm (Figure 1). The measurements were made at 0.5 cm intervals. A large hiatal hernia was tentatively defined as having a diameter ≥ 4 cm.

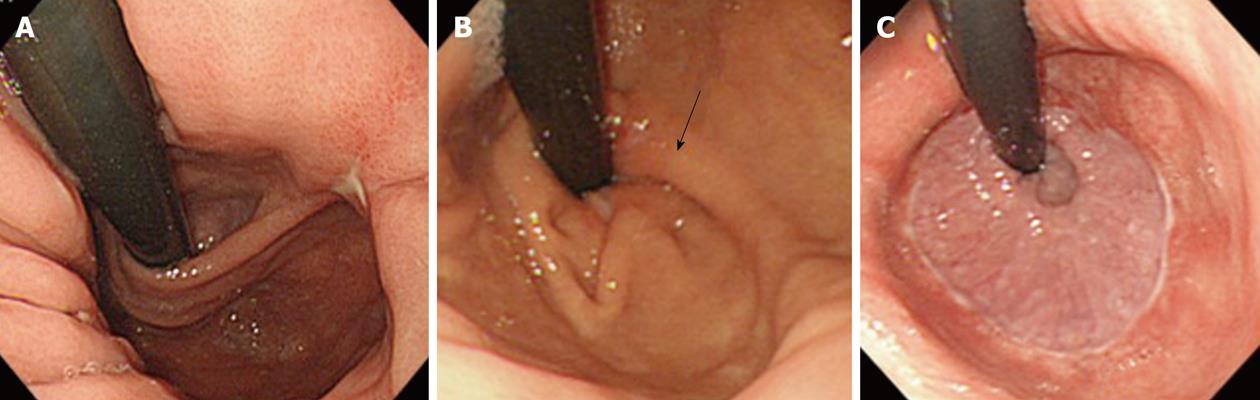

A fold or ridge that surrounded the gastric cardia was designated as a gastroesophageal flap valve (GEFV). GEFV status was assessed using the still images of the retroflex views of the gastric cardia. A GEFV composed of a sharp fold that firmly surrounded the cardia was defined as an intact GEFV, which corresponded to grade I in Hill’s classification[5,6]. A loose and dull fold or disappearance of the fold was classified as an impaired GEFV, which corresponded to grade II-VI (Figure 2).

Reflux esophagitis was evaluated using the Los Angeles classification[7]. Patients with mucosal breaks were defined as having reflux esophagitis (grade A-D). The status of gastric mucosal atrophy was assessed using the Kimura-Takemoto classification[8]. The closed and open types were defined according to the presence of gastric mucosal atrophy.

GEFV status, hernia size, and the existence of reflux esophagitis and Cameron lesions were evaluated separately by three endoscopists, who were blinded to the clinical information. When there was a lack of consensus among the three endoscopists regarding the results obtained for the endoscopic factors, the matching results (if available) from two of the three endoscopists were adopted. If there were no matched results between the three endoscopists, they re-examined together the endoscopic still images and reached a consensus.

The parameters of age, sex, hiatus diameter, GEFV status, long-term nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) intake, gastric atrophy, and hemoglobin level were examined for associations with Cameron lesions and reflux esophagitis. Long-term NSAID intake was defined as the use of any NSAID, including low-dose aspirin, for at least 3 d a week in the previous month. The associations were evaluated by univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses. When the P-value was less than 0.05, the difference was considered to be statistically significant. All analyses were performed using the STATA 8.0 software (STATA Inc., College Station, TX, USA).

Of the 16 831 patients who underwent EGD, 4658 (27.7%) were identified as having hiatal hernias, and 49 (0.3%; 24 male and 25 female) met the criteria for large hiatal hernias. The mean age of the patients with large hiatal hernias was 69.8 years (range: 41-90 years). The indications for EGD for the 49 patients were as follows: epigastralgia (n = 12), heartburn (n = 11), anemia (n = 6), melena or hematemesis (n = 4), dysphagia (n = 2), vomiting (n = 2), and others (n = 12).

Cameron lesions and reflux esophagitis were found in five (10%) and 24 (49%) of the patients with large hiatal hernias, respectively. In contrast, Cameron lesions and reflux esophagitis were found in 0 (0%) and 1253 (8.4%) of the patients without large hiatal hernias, which indicated significant associations between large hiatal hernias and these two disorders. However, Cameron lesions concomitant with reflux esophagitis were not detected in any of the patients with large hiatal hernias.

The results are shown in Table 1. Univariate analysis demonstrated significant associations between Cameron lesions and the clinico-endoscopic factors of NSAID intake, intact GEFV, and hemoglobin level in the 49 patients with large hiatal hernias. Although reflux esophagitis was found in 54.5% of the patients without Cameron lesions, it was not found in any of the patients with such lesions. Multivariate regression analysis showed a significant association between the presence of Cameron lesions and NSAID intake. As all of the patients with Cameron lesions showed intact GEFV, the association between Cameron lesions and GEFV status could not be evaluated adequately in the multivariate regression analysis.

| Univariate regression | Multivariate logistic regression | |||

| Cameron | Non-Cameron | Odds ratio | 95% CI | |

| No. of patients | 5 | 44 | - | - |

| Age (mean ± SD, yr) | 68-84 (77.2 ± 6.4) | 41-90 (77.0 ± 11.9) | - | - |

| Gender (male:female) | 0:5 | 24:20 | - | - |

| Gastric atrophy (%) | 0.4 | 0.5 | - | - |

| Erosive esophagitis (%) | 0 | 0.545 | - | - |

| Intact GEFV (%) | 100 | 18.1b | Can not be evaluated | - |

| NSAID intake (%) | 80 | 18.2a | 12.0a | 1.07-134.1a |

| Hemoglobin level (g/dL) | 7.2 ± 2.2a | 12.7 ± 1.8a | - | - |

The results are shown in Table 2. Univariate analysis demonstrated significant associations between reflux esophagitis and the clinico-endoscopic factors of sex and intact GEFV. Reflux esophagitis was frequently observed in male patients and in patients without intact GEFV. Multivariate regression analysis showed a significant reverse association between reflux esophagitis and intact GEFV.

| Univariate regression | Multivariate logistic regression | |||

| Reflux esophagitis | No esophagitis | Odds ratio | 95% CI | |

| No. of patients | 24 | 25 | - | - |

| Age (mean ± SD, yr) | 41-87 (67.3 ± 14.1) | 52-90 (72.2 ± 8.4) | - | - |

| Gender (male:female) | 17:7 | 7:18a | 2.66 (male) | 0.73-9.7 |

| Gastric atrophy (%) | 34.6 | 64 | - | - |

| Erosive esophagitis (%) | 8.3 | 44a | 0.17a | 0.03-0.95a |

| Intact GEFV (%) | 0 | 20 | - | - |

| NSAID intake (%) | 12.5 | 36 | - | - |

| Hemoglobin level (g/dL) | 12.5 ± 1.9 | 11.6 ± 2.9 | - | - |

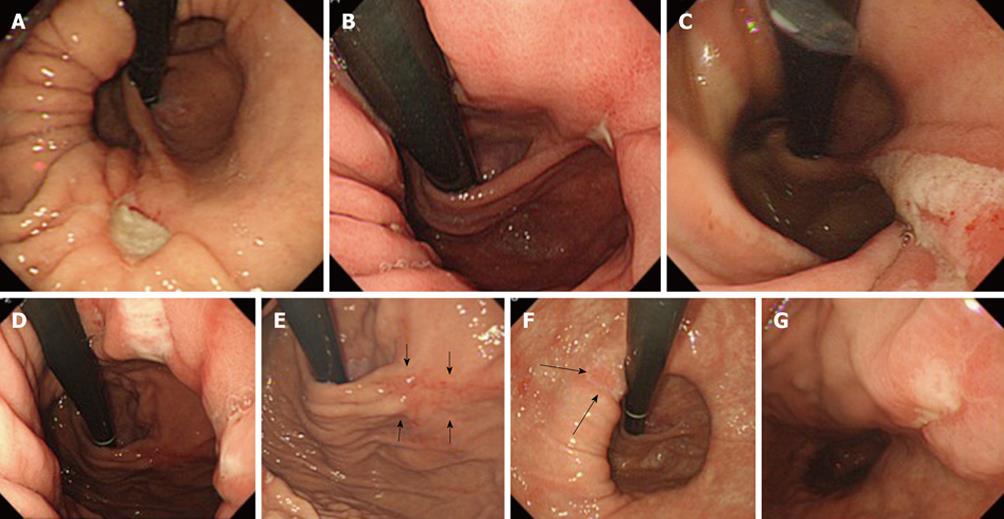

The results are shown in Figure 3. Five patients with large hiatal hernias presented with Cameron lesions. Two of these patients (#3 and #4) showed multiple linear erosions or ulcers that resembled the lesions described by Cameron et al[3]. In contrast, three of the patients showed solitary, non-linear lesions. In three patients (#1-#3) the lesions were localized to the crossing of the hiatal neck and the extension of the GEFV fold on the anterior gastric wall. In patient #4, there was no open ulcer at the crossing of the hiatal neck and the extension of the GEFV fold, although an ulceration scar was noted at the point at which the GEFV fold diverged from the anterior stomach wall (arrows in Figure 3).

Large hiatal hernias were identified in 0.3% of the patients referred to an academic referral center for diagnostic EGD. For this population, we found significant associations between the presence of large hiatal hernias and Cameron lesions or reflux esophagitis. These two disorders, which individually are linked with large hiatal hernias, were not detected concomitantly in any patient. GEFV status clearly differentiated the clinical phenotypes of large hiatal hernias into Cameron lesions or reflux esophagitis. Although the Cameron lesions were found exclusively in patients with intact GEFV, reflux esophagitis was frequently found in those with impaired GEFV.

GEFV contributes to the barrier functions against gastroesophageal reflux. The sling fibers of the stomach, which are located below the lower esophageal sphincter, are associated with a valve mechanism through which the pressure in the gastric fundus creates a flap that presses against the lower end of the esophagus[9]. GEFV status has been proposed as a useful predictor of gastroesophageal reflux disease[5,10,11]. In the present study, we have demonstrated that the anti-reflux mechanism of GEFV functions effectively, even in patients with large hiatal hernias, who are generally considered to have impaired barrier functions against gastroesophageal reflux.

All of the patients with Cameron lesions had intact GEFV, and 80% of the lesions were located at the point where the intact and sharp fold of the GEFV diverged from the stomach wall, especially on the anterior wall. As shown in Figure 1, the fold of the GEFV is speculated to be stretched excessively at the points where the fold diverges from the stomach wall. Although the mechanisms that underlie the onset of Cameron lesions remain unclear, mucosal ischemia might result from the accumulation of excessive loads at a point on the hiatus neck and/or the extension of the GEFV. Mucosal injury might be exacerbated by the combination of mechanical loading and NSAID intake, which has been significantly linked with Cameron lesions.

Although Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is one of the main causes of gastric ulcer, the status was not examined systemically in this case series. We tested H. pylori status in four of five patients with Cameron lesions. Three and one of these four patients were negative and positive for H. pylori, respectively. Since the H. pylori-positive rate of the tested patients with Cameron lesions is lower than the rate (60%-80%) in elderly Japanese patients, H. pylori infection might not be the major ulcerogenic factor in Cameron lesions. One of the limitations in the present study is that we could not obtain the information on anti-secretory drug intake in all patients. Therefore, it is difficult to evaluate the association between anti-secretory drug intake and the clinical phenotypes seen in large hiatal hernia.

Cameron et al[3] have described multiple linear erosions on the gastric folds of the hiatus neck as a distinct entity. However, lesions of various shapes (i.e. linear, oblong or round) have been reported[4]. For three of the cases in the present study, the lesions were solitary and non-linear, and appeared to be different from the lesions demonstrated in the original article. Gastric erosions or ulcers located on the hiatus neck might have different etiologies. For example, multiple linear erosions or red streaks are often observed in other disorders, such as alkaline reflux gastritis, or in the antrum of the H. pylori-negative stomach[12]. Further studies with larger populations of patients with Cameron lesions might increase our understanding of the various etiologies of this disorder.

Endoscopic diagnosis of a hiatal hernia is not easy, and accurate measurement of hernial size is difficult[11,13]. Most investigators define hernial size as the distance between the Z-line and diaphragmatic crus using the length markings on the endoscope (most of the markings are at 5-cm intervals). This application of endoscopy has been shown to be unreliable owing to the large inter-observer variability[14]. It is also difficult to ensure that the tip of the endoscope is located precisely at the Z-line or diaphragmatic crus, as the circumferential distance from these landmarks to the incisors can vary. In cases of para-esophageal hernias without sliding hernias (type II hiatus hernias)[15], measurements of this distance are not valid for assessing the size of an esophageal hernia. In the present study, which included type II hiatus hernias, hernial size was defined as the diameter of the neck of the hernia sac in images taken of the retroflex views of the gastric cardia. The measurement of hiatus diameter by comparison with the endoscope shaft is relatively objective, and hiatus diameter might be valid for assessing the size of a type II hiatus hernia. However, the hiatus diameter does not necessarily reflect the distance between the Z-line and diaphragmatic crus, even if these two parameters show strong correlation. Therefore, our definition of large hiatal hernias as having hiatus diameter ≥ 4 cm is tentative, and confirmation of the results obtained in the present study in prospective studies using both types of measurement is required.

In conclusion, GEFV status and NSAID intake differentiate the clinical phenotypes of patients with large hiatal hernias. Cameron lesions are found exclusively in patients with intact GEFV, and reflux esophagitis is frequently found in patients with impaired GEFV. NSAID intake and mechanical loading could contribute to the onset of Cameron lesions.

Gastric erosions or ulcers, located on or near the neck of a large hiatal hernia sac, are designated as Cameron lesions. Large hiatal hernias are involved in reflux esophagitis and Cameron lesions.

Cameron lesions and reflux esophagitis are mutually exclusive lesions that can be distinguished by the status of gastroesophageal flap valve (GEFV). Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) intake is linked to the presence of Cameron lesions.

The authors have demonstrated that the anti-reflux mechanism of GEFV functions effectively even in a large hiatal hernia. Further investigations with manometer and pH monitoring might confirm the barrier function of GEFV and the etiology of Cameron lesions.

It is known that Cameron lesions recur frequently and cause chronic anemia. Conservative treatment such as anti-secretory drug and iron drug intake are effective for Cameron lesions. Sometimes blood transfusion might be necessary for treatment.

This is an interesting paper about the association between hiatal hernia and pathological changes in esophageal and gastric mucosa represented by esophagitis and Cameron lesions. The authors also evaluated the effect of treatment with NSAID on the development of these mucosal changes. In addition, they have presented an alternative method for estimation of hiatal hernia size.

Peer reviewers: Dr. Andrzej Dabrowski, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Gastroenterology and Internal Medicine, Medical University of Bialystok, ul. M. Sklodowska-Curie 24A, 15-276 Bialystok, Poland; Wojciech Blonski, MD, PhD, University of Pennsylvania, GI Research-Ground Centrex, 3400 Spruce St, Philadelphia, PA 19104, United States

S- Editor Wang YR L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Zheng XM

| 1. | Patti MG, Goldberg HI, Arcerito M, Bortolasi L, Tong J, Way LW. Hiatal hernia size affects lower esophageal sphincter function, esophageal acid exposure, and the degree of mucosal injury. Am J Surg. 1996;171:182-186. |

| 2. | Jones MP, Sloan SS, Rabine JC, Ebert CC, Huang CF, Kahrilas PJ. Hiatal hernia size is the dominant determinant of esophagitis presence and severity in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1711-1717. |

| 3. | Cameron AJ, Higgins JA. Linear gastric erosion. A lesion associated with large diaphragmatic hernia and chronic blood loss anemia. Gastroenterology. 1986;91:338-342. |

| 4. | Weston AP. Hiatal hernia with cameron ulcers and erosions. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1996;6:671-679. |

| 5. | Hill LD, Kozarek RA, Kraemer SJ, Aye RW, Mercer CD, Low DE, Pope CE 2nd. The gastroesophageal flap valve: in vitro and in vivo observations. Gastrointest Endosc. 1996;44:541-547. |

| 6. | Hill LD, Kozarek RA. The gastroesophageal flap valve. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;28:194-197. |

| 7. | Armstrong D, Bennett JR, Blum AL, Dent J, De Dombal FT, Galmiche JP, Lundell L, Margulies M, Richter JE, Spechler SJ. The endoscopic assessment of esophagitis: a progress report on observer agreement. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:85-92. |

| 8. | Kimura K, Takemoto T. An endoscopic recognition of the atrophic border and its significance in chronic gastritis. Endoscopy. 1969;1:87-97. |

| 9. | Thor KB, Hill LD, Mercer DD, Kozarek RD. Reappraisal of the flap valve mechanism in the gastroesophageal junction. A study of a new valvuloplasty procedure in cadavers. Acta Chir Scand. 1987;153:25-28. |

| 10. | Contractor QQ, Akhtar SS, Contractor TQ. Endoscopic esophagitis and gastroesophageal flap valve. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;28:233-237. |

| 11. | Kinoshita Y, Adachi K. Hiatal hernia and gastroesophageal flap valve as diagnostic indicators in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:720-721. |

| 12. | Gordon C, Kang JY, Neild PJ, Maxwell JD. The role of the hiatus hernia in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:719-732. |

| 13. | Kawabe T, Maeda S, Ogura K, Yamaji Y, Okamoto M, Yoshida H, Shiratori Y, Omata M. Antral red streaking is a negative endoscopic sign for Helicobacter pylori infection. Dig Endosc. 2002;14:87-92. |

| 14. | Guda NM, Partington S, Vakil N. Inter- and intra-observer variability in the measurement of length at endoscopy: Implications for the measurement of Barrett's esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;59:655-658. |