Published online Dec 21, 2010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i47.6016

Revised: August 30, 2010

Accepted: September 7, 2010

Published online: December 21, 2010

AIM: To assess the benefits and limits of surgery for primary hepatic lymphoma (PHL), and probability of survival after postoperative chemotherapy.

METHODS: A retrospective analysis was undertaken to determine the results of surgical treatment of PHL over the past 8 years. Only nine patients underwent such treatment. The detailed data of diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis were carefully studied.

RESULTS: All patients were mistaken as having α-fetoprotein-negative hepatic cancer before pathological diagnosis. The mean delay time between initial symptoms and final diagnosis was 26.8 d (range: 14-47 d). Hepatitis B virus infection was noted in 33.3% of these patients. Most of the lesions were found to be restricted to a solitary hepatic mass. The surgical procedure performed was left hepatectomy in five cases, including left lateral segmentectomy in three. Right hepatectomy was performed in three cases and combined procedures in one. One patient died on the eighth day after surgery, secondary to hepatic insufficiency. The cumulative 6-mo, 1-year, and 2-year survival rates after hepatic surgery were, respectively, 85.7%, 71.4%, and 47.6%. One patient survived for > 5 years after surgery without any signs of recurrence until latest follow-up, who received routine postoperative chemotherapy every month for 2 years and then regular follow-up. By univariate analysis, postoperative chemotherapy was a significant prognostic factor that influenced survival (P = 0.006).

CONCLUSION: PHL is a rare entity that is often misdiagnosed, and has a potential association with chronic hepatitis B infection. The prognosis is variable, with good response to early surgery combined with postoperative chemotherapy in strictly selected patients.

- Citation: Yang XW, Tan WF, Yu WL, Shi S, Wang Y, Zhang YL, Zhang YJ, Wu MC. Diagnosis and surgical treatment of primary hepatic lymphoma. World J Gastroenterol 2010; 16(47): 6016-6019

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v16/i47/6016.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v16.i47.6016

Primary hepatic lymphoma (PHL) is confined to the liver with no evidence of lymphomatous involvement in the spleen, lymph nodes, bone marrow, or other lymphoid structures[1]. PHL is a very rare malignancy, and constitutes about 0.016% of all cases of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma[1]. Most patients are treated with chemotherapy, with some physicians employing a multimodality approach[2]. However, the optimal therapy is still unclear and the outcomes are uncertain. The purpose of this short report is to define the correct management of PHL with the help of nine clinical cases observed in the past 8 years.

In view of the policy to try to resect hepatic lymphoma completely whenever possible, the charts of all patients operated upon for this condition from January 2002 to March 2010 were reviewed retrospectively. The diagnosis of PHL was defined[3]: (1) at the time of disease presentation, the patient’s symptoms were caused mainly by the liver involvement; (2) there was an absence of palpable lymphadenopathy, and no radiological evidence of distant lymphadenopathy; and (3) there was an absence of leukemic blood involvement in the peripheral blood smear. Thus, patients with splenic, lymph node, or bone marrow involvement were excluded. During this period, only nine patients met these criteria. The analyses included sex, age, information concerning PHL, the type of liver surgery performed, postoperative therapy, the associated morbidity and mortality, and overall survival. The follow-up was complete for all nine patients.

The clinicopathological factors were analyzed for prognostic significance using a Kaplan-Meier product-limit method with a log-rank test. Significance was established at P < 0.05. Statistical calculations were performed by a statistical analysis program package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

The clinicopathological characteristics of the patients are depicted in Table 1. PHL commonly presents at 51 years of age (range: 28-78 years), with a male to female ratio of 0.8:1. The most common presenting symptom is abdominal pain or discomfort, which occurs in 55.6% of patients. Clinical examination revealed the presence of palpable abdominal masses in 22.2% of cases. All patients were misdiagnosed before pathological diagnosis. The mean delay time between initial symptoms and final pathological diagnosis was 26.8 d (range: 14-47 d). Diffuse large B-cell lymphomas were the most common type of PHL (66.7% of cases). The next most common type was mucosa-associated B-cell lymphoma, found in 22.2% of cases, followed by peripheral T-cell lymphoma (11.1%).

| Clinicopathological characteristics | Value (%) |

| No. of patients | 9 |

| Median age (at the time of surgery) | 51.4 yr (range: 28-78 yr) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 4 |

| Female | 5 |

| Hypertension | 1 |

| Rheumatic heart disease | 1 |

| Hepatitis B infection | 3 (33.3) |

| Hepatitis C infection | 1 (11.1) |

| PHL | |

| Median diameter of PHL lesion | 5.0 cm (range: 1.0-10.0 cm) |

| No. of PHL lesions | |

| Solitary | 8 |

| Multiple | 1 |

| Site of PHL lesion | |

| Left lobe | 5 |

| Right lobe | 3 |

| Bilobar | 1 |

| Vascular invasion | |

| Present | 0 |

| Absent | 9 |

| Lymph node involvement | |

| Present | 1 |

| Absent | 8 |

| Interruption of hepatic hilum | |

| Present | 9 (14.0 ± 4.2 min, range: 8-20 min) |

| Absent | 0 |

| Type of liver resection | |

| Left hepatectomy | 5 |

| Right hepatectomy | 3 |

| Combined procedures | 1 |

| Length of operation | 110 ± 59 (range: 50-255 min) |

| Blood loss of operation | 211 ± 74 (range: 100-300 mL) |

| Adjuvant regional therapy | |

| Present | 5 (55.6) |

| Absent | 4 (44.4) |

Liver function tests, including transaminases, alkaline phosphatase, lactate dehydrogenase and bilirubin were abnormal in 33.3% of patients. As the bone marrow was not involved, blood counts were within the normal range in most patients, except for three with marked splenomegaly related to liver dysfunction. Tests for human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus (HBV), and hepatitis C virus (HCV) were also carried out. In all patients, α-fetoprotein (AFP) and carcinoembryonic antigen were not significantly elevated. Hypercalcemia and coagulation abnormalities were not found in any of our patients. HBV infection was noted in 33.3% of these patients and hepatitis C in 11.1%.

The most common presentation was a solitary lesion, which occurred in about 77.8% of cases, followed by multiple lesions in about 22.2% of patients. Ultrasound was performed in all the patients and usually demonstrated hypoechoic lesions to the surrounding normal liver parenchyma in 88.9% of cases.

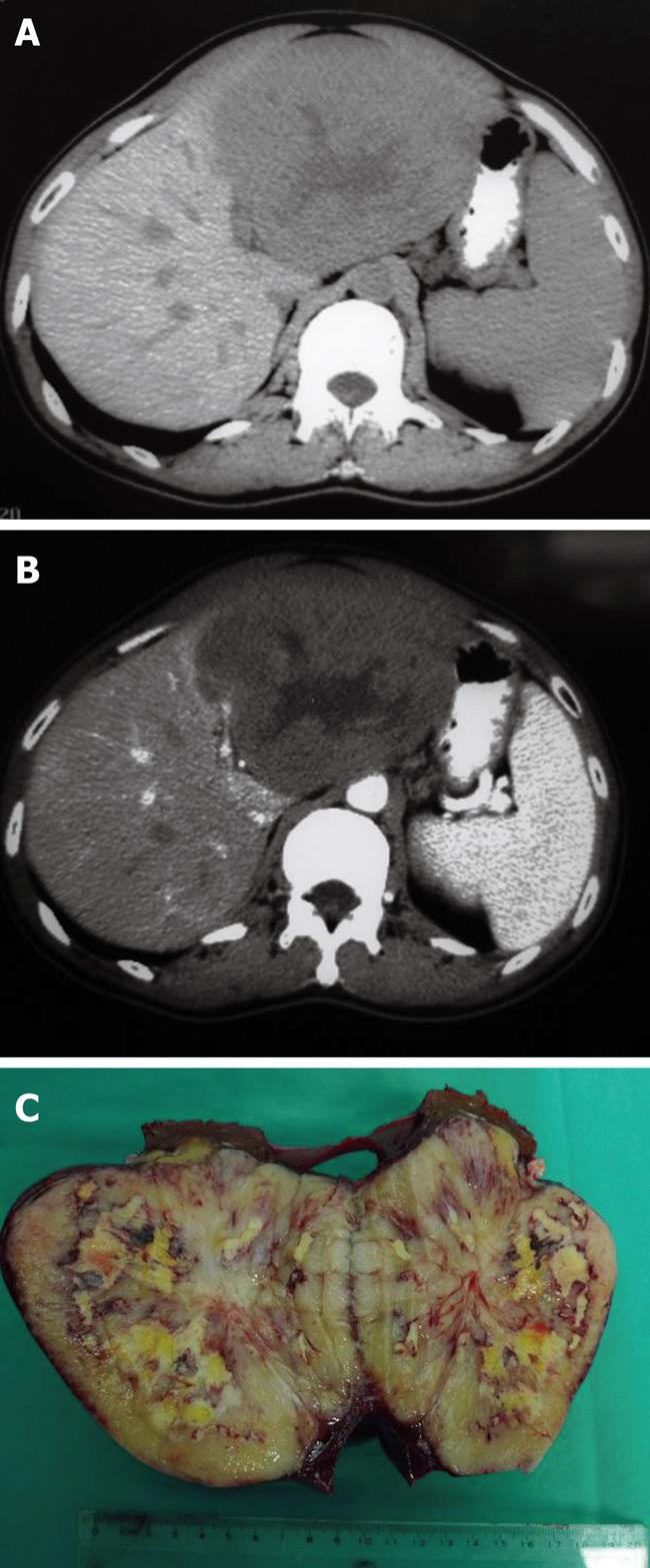

On computed tomography, PHL lesions usually appear as hypoattenuating lesions, which might have a central area of low intensity that indicates necrosis (Figure 1A). Following the administration of intravenous contrast agent, PHL lesions might show slight enhancement (Figure 1B). Most magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings in PHL were described as hypointense on T1-weighted images, and hyperintense on T2-weighted images in our patients.

Liver resection was performed in all cases. In eight patients, the resection was classified as curative, whereas one patient had palliative resection with a portal lymph-node-positive biopsy. The distribution of surgical procedures was left hepatectomy in five patients (55.6%), right hepatectomy in three (33.3%), and combined procedure in one (11.1%). In the postoperative course, one patient died on the eighth day after surgery, secondary to hepatic insufficiency. Postoperative chemotherapy was administered to five patients.

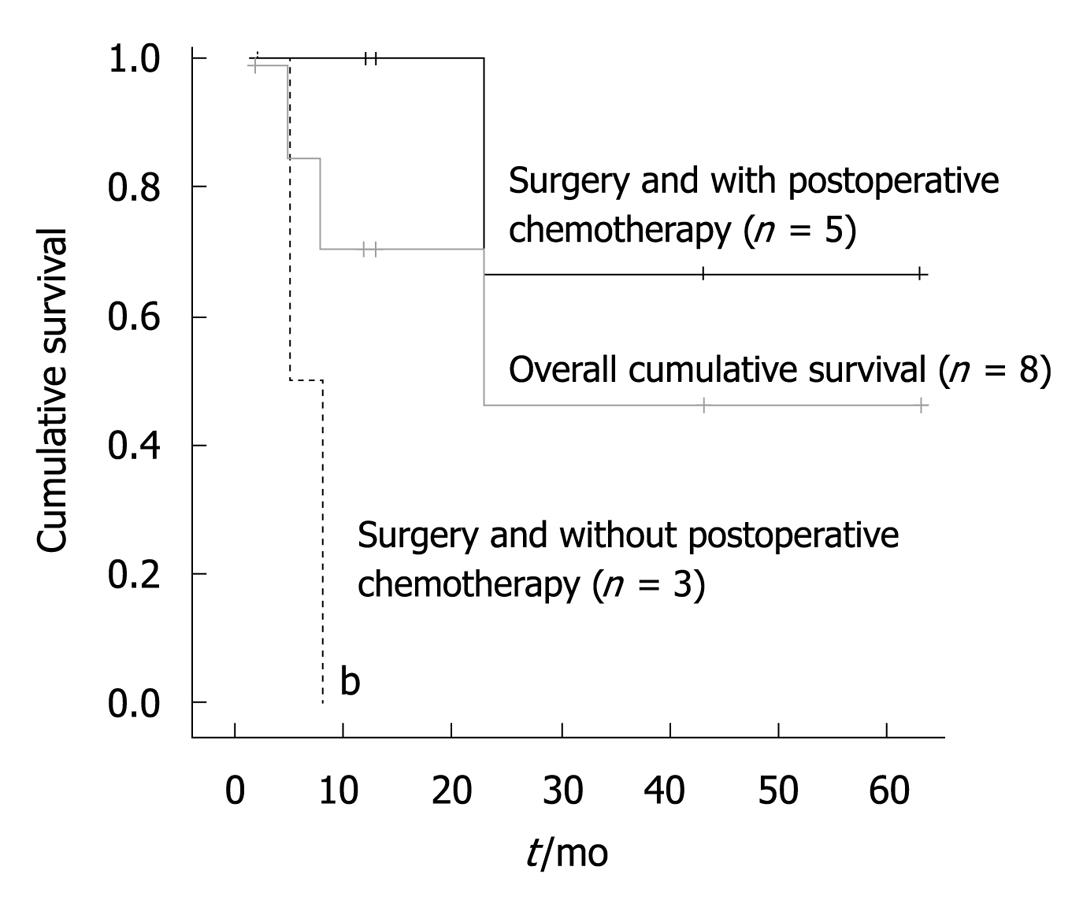

The cumulative 6-mo, 1-year and 2-year survival rate was 77.8%, 66.7%, and 55.6%, respectively, with a median survival of 23 mo. One patient was also alive and tumor-free for > 5 years after resection. Among the factors considered, postoperative chemotherapy (P = 0.006) was the only significant prognostic factor for survival (Figure 2).

We suggest that our patients had PHL because we found only liver tumor and no lymphadenopathy or bone marrow lesions. Although the liver contains lymphoid tissue, host factors can make the liver a poor environment for the development of malignant lymphoma[4]. Therefore, PHL is rare. In our study, PHL in men was less frequent than in women, which did not accord with the previously reported trend towards male predominance[1-5].

The etiology of PHL is unknown, although several possible factors such as hepatitis, cirrhosis, and immunosuppressive drugs have been proposed[3]. There appeared to be a strong association between PHL and HBV in our patients. Hepatitis B was found in 33.3% of patients. In contrast, the prevalence of hepatitis C was very low, with only one patient having the infection. However, some authors have revealed a variety of possible associations between PHL and chronic HCV infection[6-8].

Conflicting theories exist on the association of HBV infection and PHL[3,9-11]. Aozasa et al[9] have reported a 20% prevalence of hepatitis B surface antigen positivity in a series of 69 patients with PHL, in which 52 patients were from western countries and 17 from Japan. Chronic antigenic stimulation by HBV has been postulated to play a role in the development of PHL[10]. Based on all these data, it is likely that some association between PHL and HBV does in fact exist. However, the high prevalence of HBV infection in the present study perhaps corresponded to the high HBV seropositivity in China of 10% in the general population[12].

Although it remains uncertain to what extent HBV contributes to the development of PHL, a host environment with impaired immunity might play an important role[6,7,13]. Therefore, we hypothesize that chronic HBV infection, as with our three patients, could have impaired host immunity, which subsequently led to accelerated development of PHL. If this hypothesis is confirmed, suppression from HBV infection or from complications related to chronic viral infections could be crucial steps in preventing carcinogenesis of PHL.

Due to the rarity of this disease entity, the non-specific clinical presentation, and laboratory and radiological features, PHL can be confused with focal nodular hyperplasia, primary hepatic tumors, carcinoma with hepatic metastases, and systemic lymphoma with secondary hepatic involvement[10]. In the present study, all patients were mistaken as having AFP-negative hepatic cancer before pathological diagnosis. We retrospectively performed imaging studies to discriminate between these possibilities. As in our patients, most PHL is usually hypoechoic by sonography and shows hypointensity on T1-weighted and hyperintensity on T2-weighted MRI.

The optimal therapy for PHL is still unclear and the outcomes are uncertain[5]. Most patients with PHL present with poor prognostic features. One large review of 72 patients has shown the median survival to be 15.3 mo (range: 0-123.6 mo)[14]. In our study, the median overall survival for all nine patients was 23 mo. These results are better than those previously reported and could have been due to strict patient selection and the use of postoperative chemotherapy in most patients.

Our univariate analysis revealed that postoperative chemotherapy was the only significant prognostic factor that influenced survival. In a previous study, one patient treated with surgery followed by chemotherapy and radiation was reported to be alive at 5 years following initial diagnosis[2]. Page et al[15] have stratified several pretreatment risk factors after a retrospective cohort review. Lei has proposed that, in patients with localized disease, surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy should be considered to prevent disease recurrence[3]. Therefore, we advise that good prognosis of PHL can be obtained by early surgery combined with chemotherapy in strictly selected patients.

The primary limitation of this study was the small sample size and its retrospective nature, even though this study population represents a relatively large sample in surgical management of PHL in one single center. A larger prospective series could enable us to draw more substantive conclusions with regard to the roles of postoperative chemotherapy and HBV infection in the surgical setting of PHL.

Primary hepatic lymphoma (PHL) is a rare malignancy. The rarity of the disease causes problems in diagnosis and management. The optimal therapy is still unclear and the outcomes are uncertain.

The authors reported their experience of surgical management of PHL. Satisfactory survival can be achieved by early surgery combined with postoperative chemotherapy in strictly selected patients.

| 1. | Agmon-Levin N, Berger I, Shtalrid M, Schlanger H, Sthoeger ZM. Primary hepatic lymphoma: a case report and review of the literature. Age Ageing. 2004;33:637-640. |

| 2. | Noronha V, Shafi NQ, Obando JA, Kummar S. Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the liver. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2005;53:199-207. |

| 3. | Lei KI. Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the liver. Leuk Lymphoma. 1998;29:293-299. |

| 4. | Maes M, Depardieu C, Dargent JL, Hermans M, Verhaeghe JL, Delabie J, Pittaluga S, Troufléau P, Verhest A, De Wolf-Peeters C. Primary low-grade B-cell lymphoma of MALT-type occurring in the liver: a study of two cases. J Hepatol. 1997;27:922-927. |

| 5. | Bronowicki JP, Bineau C, Feugier P, Hermine O, Brousse N, Oberti F, Rousselet MC, Dharancy S, Gaulard P, Flejou JF. Primary lymphoma of the liver: clinical-pathological features and relationship with HCV infection in French patients. Hepatology. 2003;37:781-787. |

| 6. | Chen HW, Sheu JC, Lin WC, Tsang YM, Liu KL. Primary liver lymphoma in a patient with chronic hepatitis C. J Formos Med Assoc. 2006;105:242-246. |

| 7. | Hsiao HH, Liu YC, Hsu JF, Huang CF, Yang SF, Lin SF. Primary liver lymphoma with hypercalcemia: a case report. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2009;25:141-144. |

| 8. | Kim JH, Kim HY, Kang I, Kim YB, Park CK, Yoo JY, Kim ST. A case of primary hepatic lymphoma with hepatitis C liver cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2377-2380. |

| 9. | Aozasa K, Mishima K, Ohsawa M. Primary malignant lymphoma of the liver. Leuk Lymphoma. 1993;10:353-357. |

| 10. | Ohsawa M, Tomita Y, Hashimoto M, Kanno H, Aozasa K. Hepatitis C viral genome in a subset of primary hepatic lymphomas. Mod Pathol. 1998;11:471-478. |

| 11. | Masood A, Kairouz S, Hudhud KH, Hegazi AZ, Banu A, Gupta NC. Primary non-Hodgkin lymphoma of liver. Curr Oncol. 2009;16:74-77. |

| 12. | Merican I, Guan R, Amarapuka D, Alexander MJ, Chutaputti A, Chien RN, Hasnian SS, Leung N, Lesmana L, Phiet PH. Chronic hepatitis B virus infection in Asian countries. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:1356-1361. |

| 13. | Wu SJ, Hung CC, Chen CH, Tien HF. Primary effusion lymphoma in three patients with chronic hepatitis B infection. J Clin Virol. 2009;44:81-83. |

| 14. | Avlonitis VS, Linos D. Primary hepatic lymphoma: a review. Eur J Surg. 1999;165:725-729. |

Peer reviewer: Dr. Virendra Singh, MD, DM, Additional Professor, Department of Hepatology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh 160012, India

S- Editor Sun H L- Editor Kerr C E- Editor Lin YP