Published online Sep 21, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4449

Revised: August 25, 2009

Accepted: September 1, 2009

Published online: September 21, 2009

The anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α medications demonstrate efficacy in the induction of remission and its maintenance in numerous chronic inflammatory conditions. With the increasing number of patients receiving anti-TNFα agents, however, less common adverse reactions will occur. Cutaneous eruptions complicating treatment with an anti-TNFα agent are not uncommon, occurring in around 20% of patients. Adalimumab, a fully humanized antibody against TNFα, may be expected to cause minimal immune-mediated skin reactions compared to the chimeric monoclonal antibody, infliximab. We, however, report a case of Stevens-Johnson syndrome that required hospitalization and cessation of adalimumab in a patient with Crohn’s disease (CD). In this case report, a 29-year-old male with colonic and perianal CD with associated erythema nodosum and large joint arthropathy developed severe mucositis, peripheral rash and desquamation, fevers and respiratory symptoms concomitant with a second dose of 40 mg adalimumab after a 2 mo break from adalimumab therapy. Skin biopsies of the abdominal wall confirmed erythema multiforme and the patient was on no other drugs and infective etiologies were excluded. The patient responded rapidly to IV hydrocortisone and was able to be commenced on infliximab without recurrence of the Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Desquamating skin reactions have now been described in three of the TNFα antagonists (infliximab, etanercept and adalimumab). These reactions can be serious and prescribers need to be aware of the potential mucocutaneous side effects of these agents, especially as Stevens-Johnson syndrome is associated with significant morbidity and mortality.

- Citation: Salama M, Lawrance IC. Stevens-Johnson syndrome complicating adalimumab therapy in Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(35): 4449-4452

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i35/4449.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.4449

Managing chronic diseases is one of the greatest challenges for medicine and the community today as poor management results in increased resource utilization and financial costs. The anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF)α medications, infliximab and adalimumab have demonstrated efficacy in the induction of remission, and the long-term maintenance of remission, in numerous chronic inflammatory conditions including rheumatoid arthritis (RA)[1], ankylosing spondylitis[2], psoriatic arthritis and severe chronic psoriasis[3,4]. The use of biological anti-TNFα medications in the inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) is also well accepted[5-9]. The IBDs are life-long, chronic, conditions and many patients suffer severe attacks that require hospitalization. There are many drug combinations that can be used to manage these patients, but many patients are either resistant or intolerant to the non-biological therapies available. In view of the effectiveness of anti-TNFα medications, and the long-term nature of the diseases they treat, the number of patients receiving these medications continues to increase.

As a fully humanized antibody against TNFα, adalimumab may potentially cause less immune-mediated skin reactions in comparison to infliximab. The risk, however, is still present and we report here the first case in the literature of the immune-mediated skin reaction Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), that can be attributed to the use of adalimumab.

We report here a 29-year-old male diagnosed in 2005 with ileocolonic and fistulising perianal CD associated with the extra-intestinal complications of erythema nodosum, pustular psoriasis and large joint arthropathy. In August 2007, despite the use of azathioprine (AZA) 125 mg/d, antibiotics and 5-aminosalicylic acids, he had a Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI) of greater than 300, indicating moderately severe disease activity. Endoscopy confirmed severe ulcerating inflammation of the colon and the terminal ileum. In September 2007, he was commenced on routine induction therapy with adalimumab, 160 mg at week 0, 80 mg week 2 followed by 40 mg every other week (eow) administered subcutaneously (sc). Tuberculosis had been excluded by Quantiferon gold testing and chest X-ray, while his hepatitis B and C serology were confirmed to be negative prior to commencing adalimumab treatment. Complete resolution of his colitis and healing of his perianal fistulae occurred by 12 wk. He was continued on maintenance adalimumab therapy at 40 mg (sc eow) and AZA.

In December 2007, 16 wk after commencing the adalimumab therapy, he was admitted to a district hospital for suspected cellulitis of his left leg and treated by a general physician with intravenous antibiotics. His adalimumab was withheld and AZA ceased due to concerns about infection. After 10 d on antibiotic therapy he developed a severe mucositis, peripheral rash and fever. He was transferred to the Centre for Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, Fremantle Hospital, which is a specialist IBD unit in a tertiary institution that services the southern metropolitan region of Perth, Australia. At that time his C-reactive protein was 151 mg/L (normal < 10 mg/L), Hb 90 g/L (normal 135-180 g/L), platelet 521 × 109/L (normal 150-400 × 109/L) and WBC 7.9 × 109/L (normal 4.00-11.00 × 109/L). His blood cultures were clear as was his CXR. The suspected cellulitis was diagnosed as erythema nodosum and the mucositis, peripheral rash and fever were considered to be an adverse reaction to the antibiotic combination he had received. He was commenced on prednisone for the drug reaction and his severe mucositis slowly improved while the erythema nodosum resolved over the following months on a weaning dose of oral prednisolone. Due to patient concerns that his symptoms may have been exacerbated by the adalimumab, this was not recommenced at that time.

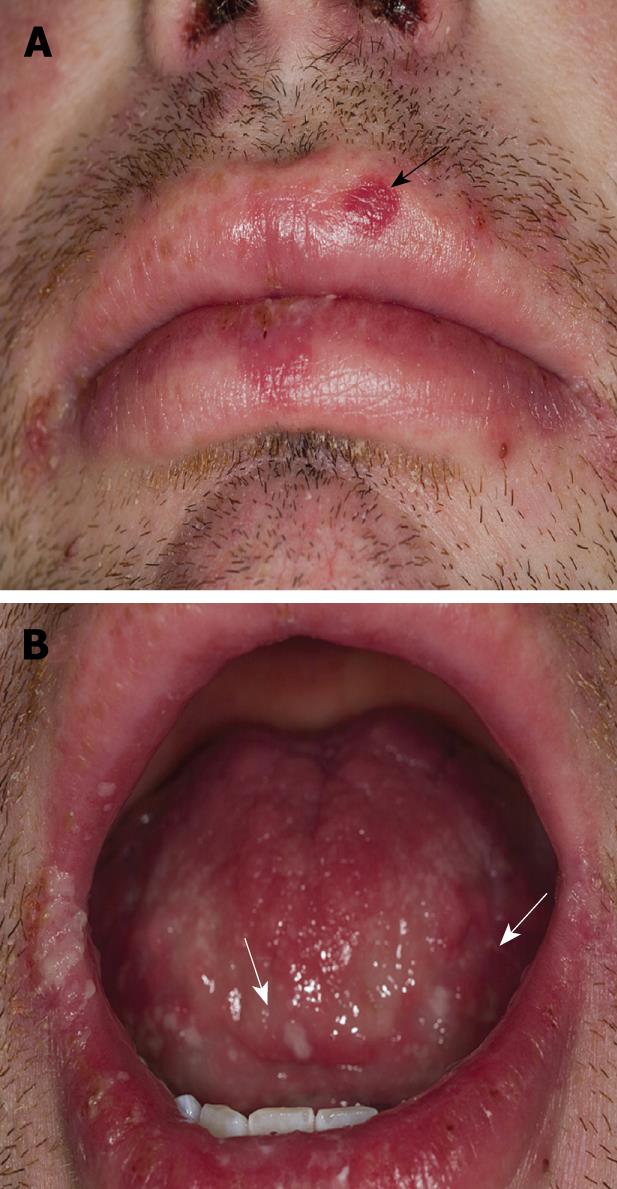

In March 2008, due to the recommencement of draining from the perianal fistulae, symptoms consistent with flaring of the colonic inflammation and reactivation of the erythema nodosum, the patient was recommenced on 40 mg adalimumab eow. A week after the first dose the patient felt that his abdominal symptoms had resolved quite significantly, the erythema nodosum had improved and there was no pain and minimal discharge from the perianal fistula. A day after receiving the second dose of 40 mg adalimumab, however, the patient became systemically unwell with fever. He developed a severe mucositis (Figure 1) and a peripheral rash with desquamation on his abdomen. He also suffered reactivation of the erythema nodosum on his legs that was confirmed to be erythema nodosum on skin biopsy.

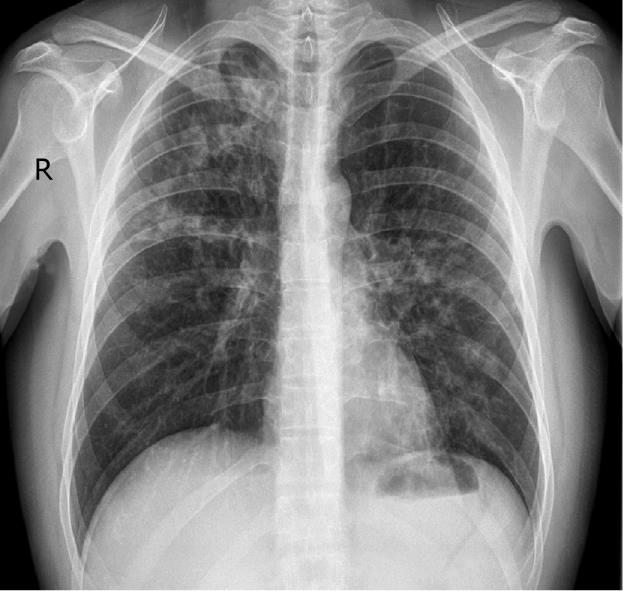

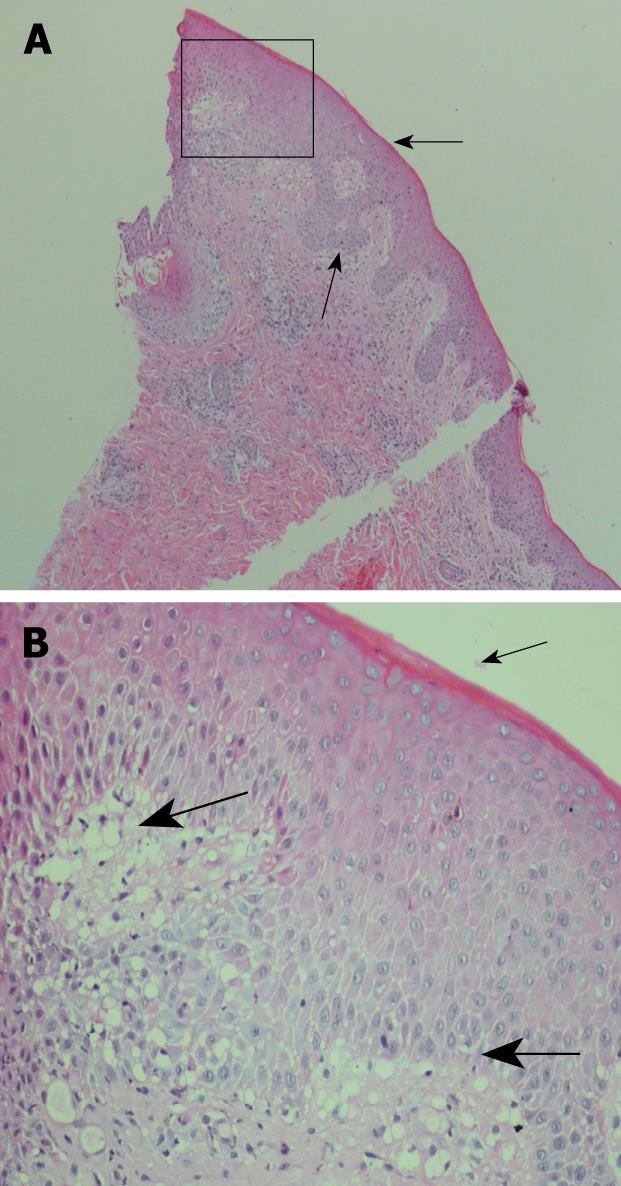

The patient was also dyspnoeic and on chest X-ray patchy opacification was observed of both mid and upper zones consistent with bronchopneumonia (Figure 2). CT scan of the thorax confirmed widespread bronchopneumonia tending to confluence in the right upper lobe. The patient was taking no other medications concurrent with the adalimumab and the adalimumab was ceased. Blood and sputum culture were negative and bacterial aetiologies and other infective causes were excluded including tuberculosis, mycoplasma pneumoniae, viral infections (HSV 1 and 2, CMV, EBV, HIV, HBV, and HCV) and rickettsia. His antinuclear antibody (ANA) remained negative throughout. Skin biopsies taken from the anterior abdominal wall rash were consistent with erythema multiforme (Figure 3). Due to the combination of mucositis membrane erosions, target lesions and epidermal necrosis with skin detachment consistent with erythema multiforme, a diagnosis of SJS was made. The chest findings also supported this diagnosis, as pulmonary infiltrates are present in 1/3 of patients with SJS. Oral doxycycline was commenced in combination with intravenous hydrocortisone with a rapid improvement in his systemic symptoms and resolution of his fever and chest X-ray infiltrates. He was transferred onto oral prednisone and his mucocutaneous symptoms resolved over the course of 3-4 wk. Due to continuing symptoms from his perianal and colonic CD, the patient was commenced on an induction regime of infliximab therapy with resolution of his CD symptoms and without reactivation of the SJS.

Cutaneous reactions in patients treated with TNFα antagonists are relatively common, but make up a heterogenous group. Recently the rate of new onset cutaneous eruptions in patients treated with infliximab for CD has been documented at 20%[10], and in a prospectively analysed series of RA patients treated with TNFα antagonists, 35/150 (23.3%) of patients developed cutaneous reactions. Eczema and psoriasis made up the majority of these (45.7%), with infections the cause of over a third (37.1%)[11]. There have been 3 reported cases of an interface dermatitis, with histological characteristics suggesting erythema multiforme, in patients treated with infliximab for RA. One of these subjects also developed a similar cutaneous reaction, confirmed on histology, after treatment with etanercept[12].

With an increasing number of patients receiving an anti-TNFα agent less common adverse reactions are bound to occur, and the physician must be aware of these potential problems. There is a spectrum of severe cutaneous adverse drug reactions that may represent variants of the same disease process, and include SJS and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) that are on a spectrum of disease severity. They are both characterised by varying degrees of disruption of the dermoepidermal junction. Clinically, each presents with a pattern characterised by the triad of mucous membrane erosions, target lesions and epidermal necrosis with skin detachment. A mortality rate of between 1%-5% is associated with SJS and TEN may be as high as 40%[13]. Erythema multiforme, erythema multiforme major and atypical erythema multiforme major, are cutaneous reactions that do not involve the mucous membranes, and are primarily observed post-infection, with the majority secondary to the herpes simplex virus, rather than as a drug reaction. The distinction, however, is often difficult to make and drugs are still implicated in up to 50% of cases of erythema multiforme.

Apart from the case reported here, there has been only 1 case in the literature of adalimumab-implicated desquamating skin reactions. This occurred in a 63-year old woman with RA after her sixth injection of adalimumab. This patient developed a papulopustular rash on the palms and soles of her feet followed by desquamation. The patient remained systemically well despite the cutaneous reaction and as there was no mucous membrane involvement she was diagnosed as having erythema multiforme, but no skin biopsy was performed. Therapy with adalimumab was discontinued and the symptoms rapidly improved without specific therapy[14]. Our case, however, was a more severe reaction with mucous membrane, skin and lung involvement that were histologically and clinically consistent with SJS. This is of particular significance due to the potentially life threatening nature of SJS. The patient was only taking one medication at the time of his second presentation and the SJS resolved on cessation of the adalimumab and treatment with hydrocortisone. The SJS can, thus, with some confidence be attributed to the use of the TNFα antagonist, adalimumab.

Desquamating skin reactions have now been described in 3 of the TNFα antagonists (infliximab, etanercept and adalimumab). Some of these reactions can be very serious and prescribers need to be aware of the potential for the mucocutaneous adverse effects from the use of these agents, particularly due to the significant morbidity and mortality that are associated with SJS and TEN.

| 1. | Ranganathan P. An update on pharmacogenomics in rheumatoid arthritis with a focus on TNF-blocking agents. Curr Opin Mol Ther. 2008;10:562-567. |

| 2. | Braun J, Deodhar A, Dijkmans B, Geusens P, Sieper J, Williamson P, Xu W, Visvanathan S, Baker D, Goldstein N. Efficacy and safety of infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis over a two-year period. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1270-1278. |

| 3. | Tzu J, Krulig E, Cardenas V, Kerdel FA. Biological agents in the treatment of psoriasis. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2008;143:315-327. |

| 4. | Ko JM, Gottlieb AB, Kerbleski JF. Induction and exacerbation of psoriasis with TNF-blockade therapy: a review and analysis of 127 cases. J Dermatolog Treat. 2009;20:100-108. |

| 5. | Rutgeerts P, Van Assche G, Vermeire S. Optimizing anti-TNF treatment in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1593-1610. |

| 6. | Targan SR, Hanauer SB, van Deventer SJ, Mayer L, Present DH, Braakman T, DeWoody KL, Schaible TF, Rutgeerts PJ. A short-term study of chimeric monoclonal antibody cA2 to tumor necrosis factor alpha for Crohn's disease. Crohn's Disease cA2 Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1029-1035. |

| 7. | Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, Mayer LF, Schreiber S, Colombel JF, Rachmilewitz D, Wolf DC, Olson A, Bao W. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn's disease: the ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1541-1549. |

| 8. | Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Enns R, Hanauer SB, Panaccione R, Schreiber S, Byczkowski D, Li J, Kent JD. Adalimumab for maintenance of clinical response and remission in patients with Crohn's disease: the CHARM trial. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:52-65. |

| 9. | Hanauer SB, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Fedorak RN, Lukas M, MacIntosh D, Panaccione R, Wolf D, Pollack P. Human anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibody (adalimumab) in Crohn's disease: the CLASSIC-I trial. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:323-333; quiz 591. |

| 10. | Peyrin-Biroulet L, Deltenre P, de Suray N, Branche J, Sandborn WJ, Colombel JF. Efficacy and safety of tumor necrosis factor antagonists in Crohn's disease: meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:644-653. |

| 11. | Lee HH, Song IH, Friedrich M, Gauliard A, Detert J, Röwert J, Audring H, Kary S, Burmester GR, Sterry W. Cutaneous side-effects in patients with rheumatic diseases during application of tumour necrosis factor-alpha antagonists. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:486-491. |

| 12. | Favalli EG, Desiati F, Atzeni F, Sarzi-Puttini P, Caporali R, Pallavicini FB, Gorla R, Filippini M, Marchesoni A. Serious infections during anti-TNFalpha treatment in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Autoimmun Rev. 2009;8:266-273. |

| 13. | Bastuji-Garin S, Rzany B, Stern RS, Shear NH, Naldi L, Roujeau JC. Clinical classification of cases of toxic epidermal necrolysis, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and erythema multiforme. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:92-96. |

Peer reviewers: Hitoshi Asakura, Director, Emeritus Professor, International Medical Information Center, Shinanomachi Renga Bldg. 35, Shinanomachi, Shinjukuku, Tokyo 160-0016, Japan; NKH de Boer, PhD, MD, Gastroenterology and Hepatology, VU University Medical Center, PO Box 7057, 1007 MB, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor O’Neill M E- Editor Yin DH