Published online Sep 21, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.4453

Revised: August 12, 2009

Accepted: August 19, 2009

Published online: September 21, 2009

The involvement of hairy cell leukemia in the liver is in the form of portal and sinusoidal cellular infiltration. Here we describe the first case of hepatic hairy cell leukemia presenting as multiple discrete lesions, which was treated successfully. We suggest that in the investigation of discrete hepatic lesions in cases of cancer of unknown primary, hairy cell leukemia should be considered. The excellent response of hairy cell leukemia to therapy highlights the need for such a consideration.

- Citation: Sahar N, Schiby G, Davidson T, Kneller A, Apter S, Farfel Z. Hairy cell leukemia presenting as multiple discrete hepatic lesions. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(35): 4453-4456

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i35/4453.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.4453

Metastases of an unknown primary site are found in about 5% of all cancer patients[1-3]. The recent advances in molecular technology, including gene expression profiling, raise the expectation for improved diagnosis of cancer of unknown primary (CUP). This is needed to identify subsets of patients who could potentially respond to therapy. The liver is involved in about a third of patients with CUP[3]. In about 50% of these patients, the primary tumor is carcinoma of the lung, colon, rectum, or pancreas. Other primary tumor sites are the liver, breast, skin (melanoma), stomach etc. Here we describe a patient with discrete hepatic masses which proved to be hairy cell leukemia. This is in contrast to the regular liver involvement by hairy cell leukemia, which is in the form of diffuse infiltration. Since treatment of this tumor is very effective, its diagnosis should not be missed.

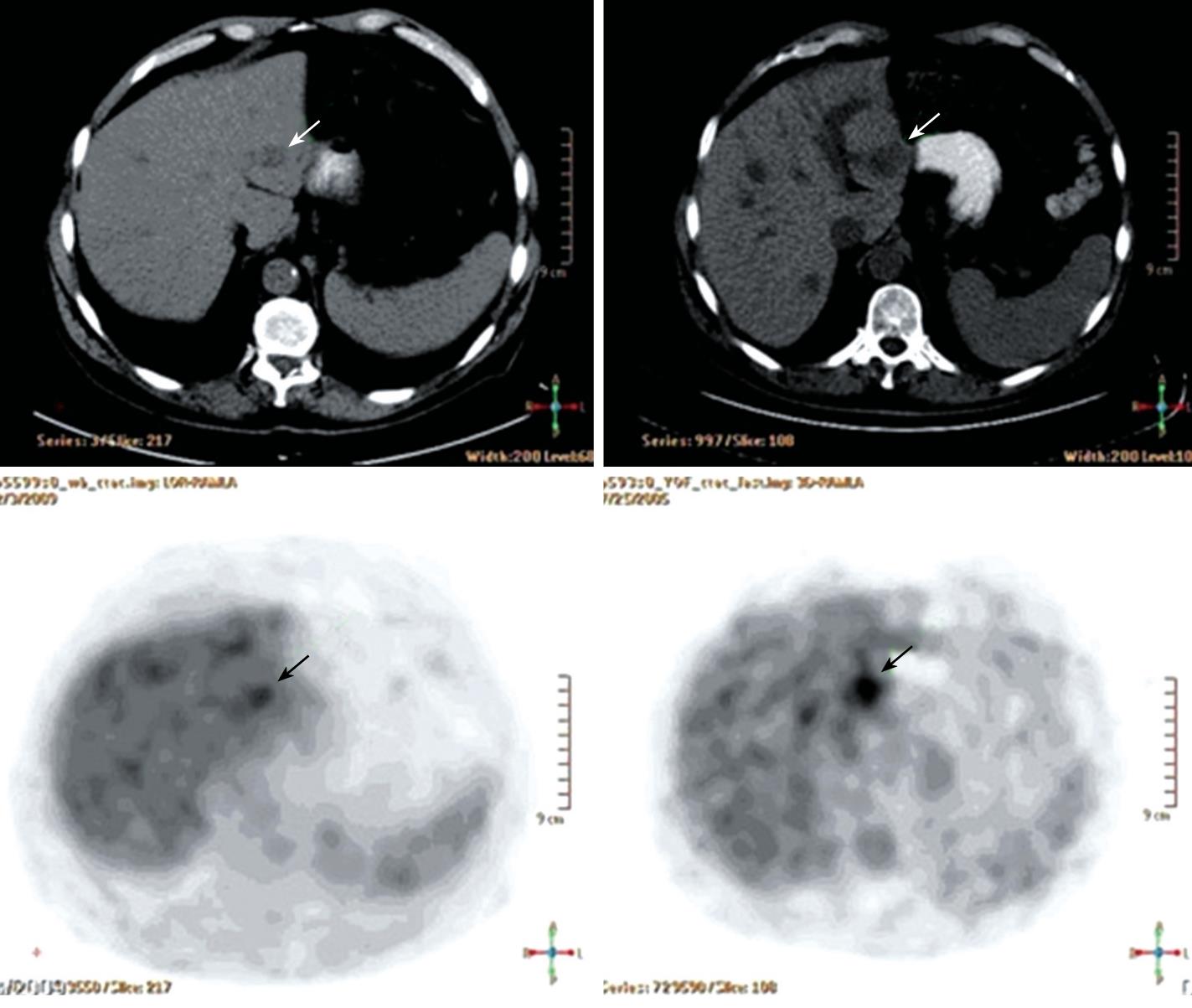

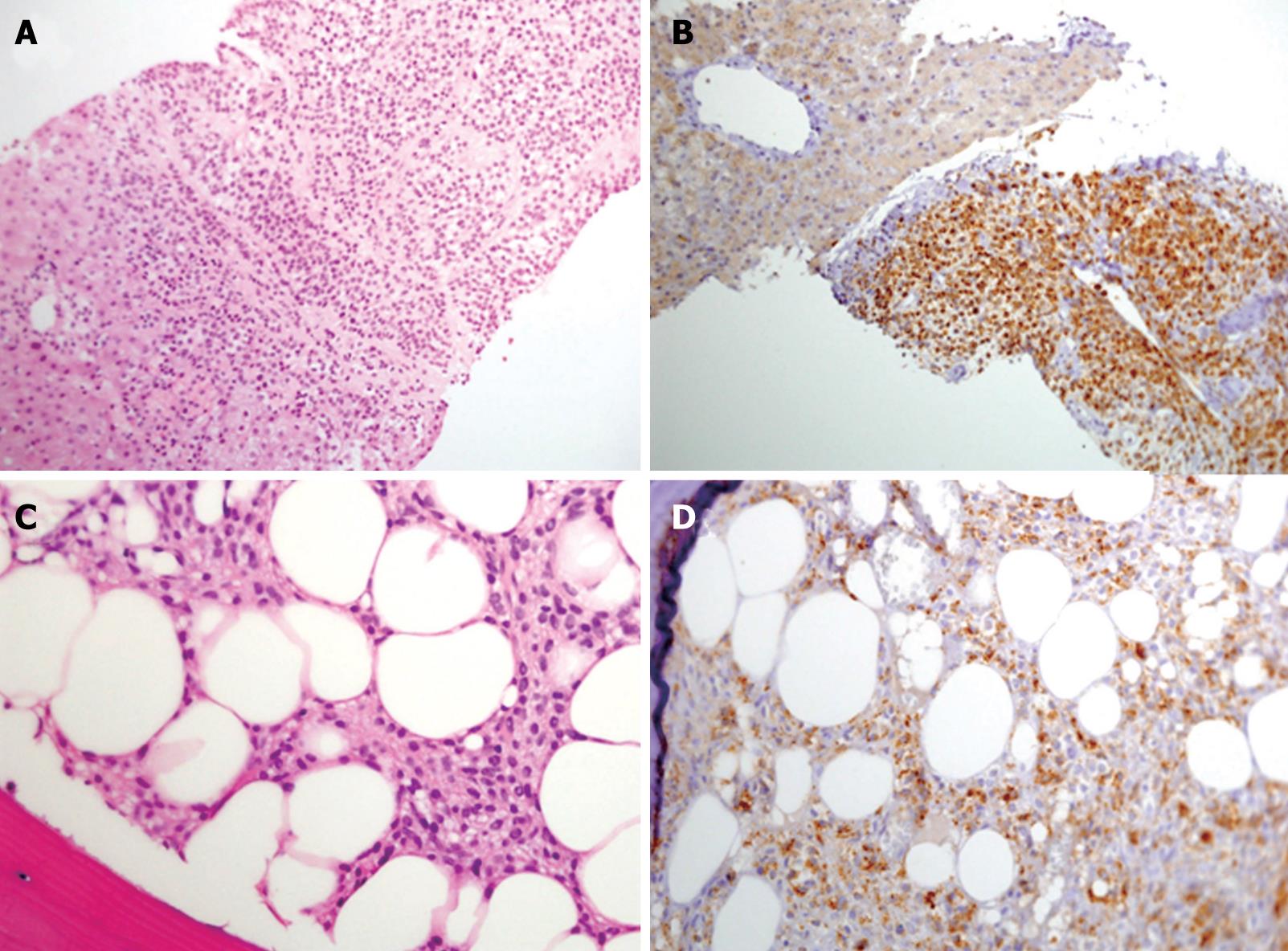

A 61-year-old male patient presented to the outpatient clinic in 2005 with complaints of paresthesia in his hands. Abdominal imaging studies, which he underwent previously, detected focal liver lesions. In 1996, an abdominal ultrasound carried out for epigastric pain, revealed two focal hepatic lesions presumed to be hemangiomas. This was verified by a red blood cell (RBC) scan. In 2000, an abdominal computed tomography (CT) study showed ten hepatic lesions of different sizes, however, no further investigation was performed. In 2003, the patient had an inferior wall myocardial infarction. His blood count showed a hemoglobin level of 132 g/L, white blood cell count of 6.7 × 109/L and a platelet count of 188 × 109/L. In 2005, a routine blood count showed hemoglobin of 111 g/L. A repeat ultrasound (US) detected multiple hepatic lesions, and an abdominal CT scan showed that the hepatic lesions had grown since the previous (2000) study. Another RBC scan again showed only two hemangiomas. Finally, a positron emission CT (PET-CT) scan showed uptake of fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) in several hepatic lesions (Figure 1B), and a decision was made to biopsy one of the lesions. On histopathological examination, the cells of the lesion were different from the known primary and metastatic tumors of the liver, and all the immunohistochemical stains performed were negative. A neuroendocrine tumor was considered the most likely morphological diagnosis, despite negative staining for the neuroendocrine antigens, synaptophysin and chromogranin A (Figure 2A).

The patient was referred to our clinic for further evaluation. He denied any weight loss, diarrhea or flushing. On physical examination he appeared well. No lymphadenopathy was noted, his abdomen was not tender, and no signs of an enlarged liver or spleen were found. His laboratory results showed pancytopenia with a hemoglobin level of 110 g/L, white blood cells of 3.5 × 109/L, and a platelet count of 120 × 109/L. All liver function tests were normal, albumin level was 40 g/L. Blood levels of adreno-cortico-trophic hormone (ACTH) and beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) were normal, urine levels of vanilmandelic acid (VMA) and 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5HIAA) were also in the normal range. An octreotide scan showed increased uptake in the liver. A bone marrow biopsy was performed, which was compatible with hairy cell leukemia with positive stains for CD-20 and Tartaric Acid Resistant Acid Phosphatase (TRAcP) (Figure 2C and D). A repeat examination of the hepatic specimen showed positive staining for CD-20 and TRAcP (Figure 2B).

The patient was started on cladribine (2-chlorodeoxyadenosine-2CDA) with a diagnosis of hairy cell leukemia with hepatic involvement. No side effects were noted. Three months after treatment, a gradual rise in his blood count was seen. A follow-up CT scan showed that the hepatic lesions had not changed in size. His paresthesia had resolved.

Two years after treatment with 2CDA his blood counts had increased, his hemoglobin level was 148 g/L, white blood cell count was 6.2 × 109/L, and platelet count was 189 × 109/L. Repeat CT and an abdominal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan showed that the lesions were similar in size to those shown on the previous CT. A repeat PET-CT scan about three years after treatment demonstrated that only one lesion in his left hepatic lobe still showed uptake of FDG, no uptake was observed in the other lesions (Figure 1A).

PET-CT scan with F18-FDG: The first PET-CT scan of 2005 (Figure 1B), shows multiple hypodense lesions of different sizes in the liver; some of the lesions show increased uptake of F18-FDG. The post-treatment PET-CT scan of 2009 (Figure 1A), shows significant improvement. All the previously hypermetabolic lesions are smaller, and all foci of increased uptake, with the exception of one, disappeared. This latter lesion, although reduced in size, still shows increased F18-FDG uptake but with lower intensity. These dynamic changes are consistent with involvement of the underlying disease. According to CT from the PET-CT scan of 2009, the lesions which did not show increased F18-FDG uptake either in 2005 or in 2009 did not change in size. This suggests that they are of a different nature i.e. hemangioma. This was proven by a labeled red blood cell nuclide scan.

Pathological findings: The submitted liver core needle biopsy was fixed in formalin (neutral 10%, pH 7.4) and embedded in paraffin wax. Sections 4 microns thick were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE). The histological sections showed liver tissue infiltrated by diffuse aggregates of small/medium-sized uniform tumor cells, with bland oval nuclei, clear cytoplasm with no well defined cytoplasmic borders. No cellular atypia or mitotic figures were demonstrated (Figure 2A). For immunophenotyping, we used the standard avidin-biotin method on the paraffin sections. The slides were immunostained in the automated system ES Ventana (Ventana Medical Systems, Inc). Immunohistochemical staining showed that the cells were positive for vimentin (V9, ZYMED Laboratories, South San Francisco, CA, USA) and negative for α-smooth muscle actin/SMA (1A4, DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark), desmin (ZC 18, ZYMED Laboratories) (muscle origin), S-100 (S-100, DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark), chromogranin (Chromogranin A, DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark), synaptophysin (Synaptophysin, Z66, ZYMED Laboratories) and CD56 (T199, DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark) (neuroendocrine origin), MNF116 (MNF116, DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark), CAM 5.2 (Zym 5.2, ZYMED Laboratories), CK7 (OTVL, BioGenex, San Ramon, CA, USA), CK20 (IT-Ks20.8, BioGenex, San Ramon, CA, USA), CEA (ZC23, ZYMED Laboratories) (epithelial origin), CD31 (JC70A, DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark), CD34 (QBEnd/10, CellMarque, Rocklin, CA, USA), (vascular origin), and α-fetoprotein (α-1 DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark), and HEPA (OCH1ES, DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark), (liver origin). The Ki67 proliferation antigen was positive in about 10% of cells. Despite the fact that the tumor cells were negative for almost all the basic non-hematological immunostains, it was decided that the morphological differential diagnosis was either a neuroendocrine tumor or a glomus tumor. One month later a bone marrow trephine biopsy was performed. The bone marrow was infiltrated by sheets of tumor cells with morphological features of hairy cell leukemia (Figure 2C). The immunohistochemical stains for CD20 (L26 DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark), and TRAcP (ZY-9C5, ZYMED Laboratories), were positive and confirmed the diagnosis of hairy cell leukemia (Figure 2D). In a revision of the liver biopsy, it became clear that the tumor cells were morphologically similar to the hairy cells in the bone marrow. The immunohistochemical stains for CD20 and TRAcP were also positive and confirmed the diagnosis of hairy cell leukemia of the liver presenting as a tumoral mass (Figure 2B).

The pathological diagnosis of cancer of unknown primary requires a careful evaluation of the morphology as well as the immunohistochemistry of the affected tissue[4]. Discrete hepatic lesions formed by infiltration of hairy cell leukemia cells were not described until last year. Hairy cell leukemia (HCL) is a rare chronic lymphoproliferative disorder usually characterized by an indolent course. The hairy cells are B cells found in the blood circulation that consist of oval nuclei and abundant cytoplasm with characteristic micro-filamentous (“hairy”) projections. Patients usually present with cytopenia and splenomegaly due to infiltration of the cells into the bone marrow and spleen[5].

Hepatomegaly can be seen in up to a third of patients[6]. Histologically, liver involvement has been described in the form of portal and sinusoidal infiltration. Some lesions in the liver have been described as angiomatous with tumor cells and blood cells filling the sinusoids[7]. Clinical features of liver involvement may include in addition to hepatomegaly, jaundice and increased levels of aminotransferases and alkaline phosphatase[7]. The mechanism of production of nodular hepatic lesions in some cases of hairy cell leukemia is unknown. It is also unclear whether there is a difference in the course and prognosis of the disease in subjects with hairy cell leukemia and hepatic diffuse vs nodular involvement.

The introduction of purine-nucleoside analogues such as cladribine for the treatment of hairy cell leukemia has dramatically changed the prognosis in affected subjects[8]. In a recent long-term follow-up study of 233 patients, Else et al[9] found that overall, the complete response rate was 80%, and median relapse-free survival was 16 years. The outcome of patients with recurrent disease has improved with the monoclonal antibody anti-CD20, rituximab[9,10].

Recently, Al-Za’abi et al[11] have reported a case of HCL presenting as a solitary liver mass 20 years after the initial presentation with splenic involvement. These clinical features enabled correct diagnosis of the hepatic mass. No details regarding the treatment and course of the patient’s disease were provided. To the best of our knowledge, our case is the first of a patient with HCL presenting with multiple discrete hepatic lesions. These lesions were present prior to the appearance of pancytopenia, which is the consequence of extensive bone marrow involvement. The patient responded to standard treatment, as seen by the disappearance of pancytopenia, and by the marked decrease in FDG uptake by the hepatic lesions.

This report highlights the need to consider the possibility of hairy cell leukemia in the investigation of discrete hepatic lesions in cases of cancer of unknown primary. The excellent response to therapy of this tumor further emphasizes the need for correct diagnosis.

| 1. | Varadhachary GR, Talantov D, Raber MN, Meng C, Hess KR, Jatkoe T, Lenzi R, Spigel DR, Wang Y, Greco FA. Molecular profiling of carcinoma of unknown primary and correlation with clinical evaluation. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4442-4448. |

| 2. | Pavlidis N, Briasoulis E, Hainsworth J, Greco FA. Diagnostic and therapeutic management of cancer of an unknown primary. Eur J Cancer. 2003;39:1990-2005. |

| 3. | Ayoub JP, Hess KR, Abbruzzese MC, Lenzi R, Raber MN, Abbruzzese JL. Unknown primary tumors metastatic to liver. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:2105-2112. |

| 4. | Oien KA. Pathologic evaluation of unknown primary cancer. Semin Oncol. 2009;36:8-37. |

| 5. | Wanko SO, de Castro C. Hairy cell leukemia: an elusive but treatable disease. Oncologist. 2006;11:780-789. |

| 6. | Polliack A. Hairy cell leukemia: biology, clinical diagnosis, unusual manifestations and associated disorders. Rev Clin Exp Hematol. 2002;6:366-388; discussion 449-450. |

| 7. | Yam LT, Janckila AJ, Chan CH, Li CY. Hepatic involvement in hairy cell leukemia. Cancer. 1983;51:1497-1504. |

| 8. | Gidron A, Tallman MS. 2-CdA in the treatment of hairy cell leukemia: a review of long-term follow-up. Leuk Lymphoma. 2006;47:2301-2307. |

| 9. | Else M, Dearden CE, Matutes E, Garcia-Talavera J, Rohatiner AZ, Johnson SA, O’Connor NT, Haynes A, Osuji N, Forconi F. Long-term follow-up of 233 patients with hairy cell leukaemia, treated initially with pentostatin or cladribine, at a median of 16 years from diagnosis. Br J Haematol. 2009;145:733-740. |

| 10. | Thomas DA, Ravandi F, Kantarjian H. Monoclonal antibody therapy for hairy cell leukemia. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2006;20:1125-1136. |

| 11. | Al-Za'abi AM, Boerner SL, Geddie W. Hairy cell leukemia presenting as a discrete liver mass: diagnosis by fine needle aspiration biopsy. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36:128-132. |

Peer reviewer: Nikolaus Gassler, Professor, Institute of Pathology, University Hospital RWTH Aachen, Pauwelsstrasse 30, 52074 Aachen, Germany

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor Webster JR E- Editor Ma WH