Published online Jul 14, 2009. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.3232

Revised: May 27, 2009

Accepted: June 3, 2009

Published online: July 14, 2009

AIM: To evaluate radiofrequency thermal ablation (RTA) for treatment of cystic echinococcosis in animal models (explanted organs).

METHODS: Infected livers and lungs from slaughtered animals, 10 bovine and two ovine, were collected. Cysts were photographed, and their volume, cyst content, germinal layer adhesion status, wall calcification and presence of daughter or adjacent cysts were evaluated by ultrasound. Some cysts were treated with RTA at 150 W, 80°C, 7 min. Temperature was monitored inside and outside the cyst. A second needle was placed inside the cyst for pressure stabilization. After treatment, all cysts were sectioned and examined by histology. Cysts were defined as alive if a preserved germinal layer at histology was evident, and as successfully treated if the germinal layer was necrotic.

RESULTS: The subjects of the study were 17 cysts (nine hepatic and eight pulmonary), who were treated with RTA. Pathology showed 100% success rate in both hepatic (9/9) and lung cysts (8/8); immediate volume reduction of at least 65%; layer of host tissue necrosis outside the cyst, with average extension of 0.64 cm for liver and 1.57 cm for lung; and endocyst attached to the pericystium both in hepatic and lung cysts with small and focal de novo endocyst detachment in just 3/9 hepatic cysts.

CONCLUSION: RTA appears to be very effective in killing hydatid cysts of explanted liver and lung. Bile duct and bronchial wall necrosis, persistence of endocyst attached to pericystium, should help avoid or greatly decrease in vivo post-treatment fistula occurrence and consequent overlapping complications that are common after surgery or percutaneous aspiration, injection and reaspiration. In vivo studies are required to confirm and validate this new therapeutic approach.

-

Citation: Lamonaca V, Virga A, Minervini MI, Di Stefano R, Provenzani A, Tagliareni P, Fleres G, Luca A, Vizzini G, Palazzo U, Gridelli B. Cystic echinococcosis of the liver and lung treated by radiofrequency thermal ablation: An

ex-vivo pilot experimental study in animal models. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15(26): 3232-3239 - URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v15/i26/3232.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.15.3232

Cystic echinococcosis is a helminthic zoonosis that can occasionally affect human beings. The organs most frequently involved are the liver and the lungs[12]. Viability and pathogenicity of the cyst are conditioned by the integrity of its germinal membrane. For many years elective treatment has been surgery (organ resection, cysto-pericystectomy)[34]. Recently percutaneous aspiration, injection and reaspiration (PAIR), using hypertonic saline or ethanol, has become a valid alternative option, principally for the liver[56]. This is now widely advocated in the treatment of uncomplicated fluid-filled liver cysts because of lower recurrence and complication rates[378]. There are, however, few reports in the literature on PAIR treatment of pulmonary echinococcosis[910]. Chemotherapy with albendazole can be used in combination with interventional procedures, but is seldom effective alone[311–13]. Both surgery and PAIR can result in post-procedure complications, namely, biliary or bronchial fistulae promoted by endocyst detachment[14–16]; chemical cholangitis or pneumonia due to passing of hypertonic saline or ethanol into the biliary or bronchial tree through a pre-existing communication[9101718]; and infection or abscess on the cyst cavity[3710]. Chemical cholangitis is a frightful complication since it invariably requires liver transplantation[17]. Radiofrequency thermal ablation (RTA) is currently used for treatment of neoplasms, primarily hepatocellular carcinoma[19–21].

To our knowledge, there is no controlled study in the literature on possible treatment of hydatid cyst with RTA. The aim of our study was to evaluate RTA for treatment of cystic echinococcosis of liver and lung in animal models (explanted organs). The primary end point was to evaluate efficacy in killing the parasite. The secondary end-points were to evaluate germinal layer adhesion status after the procedure and the effect of radiofrequency (RF) on host organ tissue outside the cyst.

Cystic echinococcosis is an endemic zoonosis in Sicily[2223]. To perform our study we used infected livers and lungs from slaughtered animals, 10 bovine and two ovine. Samples were provided by the Veterinary Service of the Region of Sicily within 12 h of their collection. By using slaughtered animals with endemic zoonosis, our study had minimal economic costs and raised no ethical concerns.

Each cyst was photographed and evaluated by ultrasound (US). Cyst volume was calculated with the ellipsoid volume formula (4/3 π abc; abc = cyst hemidiameteres). Cyst content, germinal layer adhesion status, presence of wall calcification and presence of daughter or adjacent cysts were also evaluated by US.

The ex-vivo approach, large size and superficial place of the cysts made US evaluation easy in the lung as well as the liver.

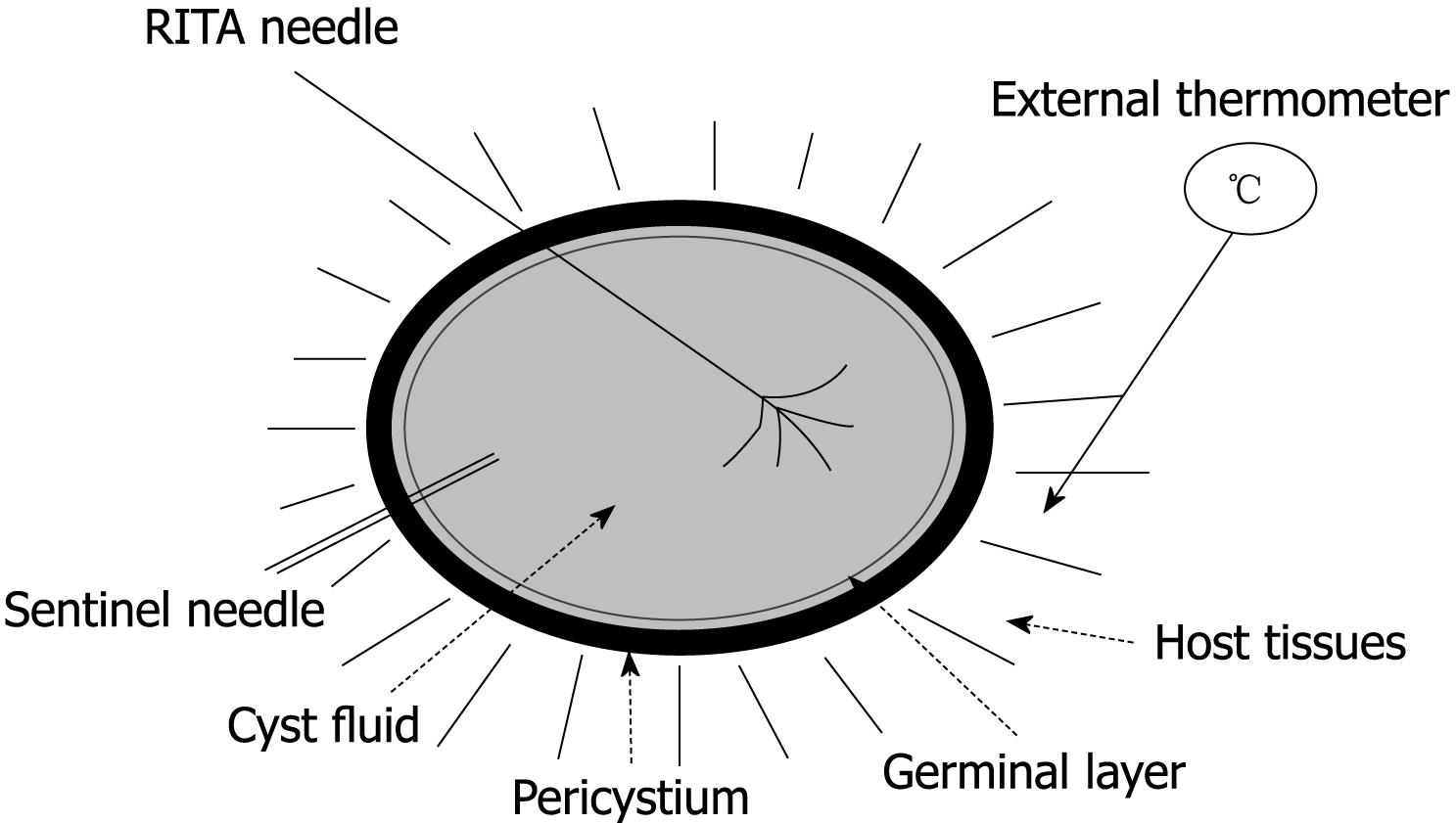

Each cyst was placed on a RITA® dispersive electrode and, under US guidance, a 9-tip expandable needle (RITA® StarBurst TM XL, RITA Medical Systems) was inserted into the cyst, expanded and connected to a RF generator (RITA Medical System 1500 X). Temperature inside the cyst was monitored by RITA needle tip temperature transducers. Under US guidance a thermometer (bimetal thermometer 0 + 120°C, probe length: 110 mm - Φ 4 mm, dial Φ 45 mm) was also placed outside the cyst, up to 1 cm from its wall, for external temperature monitoring. Both internal and external temperature was monitored throughout the procedure and for the following 20 min.

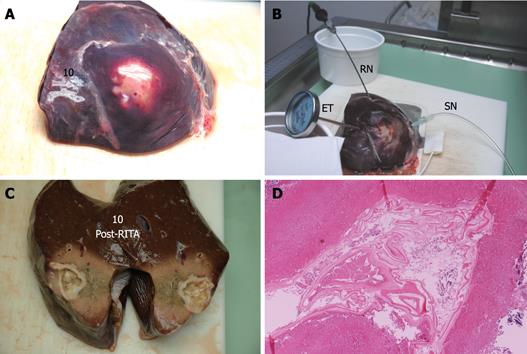

In addition to the RITA needle, a second needle, which we named “sentinel needle,” was also placed inside the cyst in order to stabilize internal cyst pressure during the procedure (Figure 1). In fact, during pre-study sessions of the treatment that we preliminarily performed in order to optimize the technical aspects of the procedure, we observed that while reaching target temperature, endocytic pressure quickly increases and invariably causes cyst rupture unless pressure stabilization is obtained. The increase in endocytic pressure is likely due to gas formation (water vapor, CO2) at the interface of the fluid/needle because of the high local temperature.

The RTA parameters we used were: 150 watts, 80°C, 7 min. Treated cysts were then sectioned and a pathology examination was performed. Histology on the samples evaluated the germinal layer, the presence of scolices, the pericystium, parenchymal cells, blood vessels, biliary ducts (liver) and the bronchial walls (lung).

All the data were stored in an Excel database and used for statistics. In addition to the treated cysts, there were also some untreated parasitic cysts randomly examined with US and histology, using the same criteria as that used for treated cysts, as an addendum to the study.

Alive cyst: histological evidence of preserved germinal layer; killed cyst: necrotic endocyst at histology.

By definition, pilot studies are conducted on a small number of cases, which makes reliable statistical correlations difficult to establish. Nevertheless, we performed a statistical analysis of our data in an attempt to identify significant trends. All values were expressed as a mean, and the Mann-Whitney U-test was used for comparison among groups. All P values were two-sided, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The Pearson test was used to investigate the linear relationship between two groups of data.

A total of 28 cysts, 16 hepatic and 12 pulmonary, were evaluated. Seventeen, treated with RTA, were the object of our study (Table 1). In addition, 11 untreated cysts, seven hepatic and four pulmonary, were randomly evaluated. All of them were unilocular with anechoic content, no wall calcification, germinal membrane adherence were observed at US, and all were alive at pathology.

| Liver (n = 9) | Lung (n = 8) | |||

| Baseline | Post-RTA | Baseline | Post-RTA | |

| Cyst volume (mL)1 | ||||

| Average | 40.5 | 14.9 | 158.7 | 57.1 |

| Range | 8.3-61.6 | 2.0-28.3 | 4.2-471 | 1.3-287.8 |

| Fluid echo pattern2 | ||||

| Anechoic | 9 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Anechoic + ground | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Disomogeneous | 0 | 9 | 0 | 8 |

| Proligera status1 | ||||

| Adhered | 9 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Focally detached | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Detached | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Wall calcification (any)1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Daughter/adjacent cysts1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Internal | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| External | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Killing rate (%)3 | - | 100 | - | 100 |

| Pericyst necrosis (cm)3 | ||||

| Mean (range) | - | 0.64 (0-2) | - | 1.57 (0.8-2.5) |

| External temperature (°C)4 | ||||

| Average of peaks | 42.9 | 52.6 | ||

| Range of peaks | 23-69 | 39-64 | ||

| Gradient T (range)5 | 11.9-58.3 | 16.9-38.7 | ||

Seventeen cysts were treated with RTA: nine hepatic, average volume 40.5 mL (range, 8.3-61.6 mL), and eight pulmonary, average volume 158.7 mL (range, 4.2-471 mL). Baseline US showed the endocyst was attached to the pericystium in 100% (9/9) of liver and 75% (6/8) of lung cysts, and focally detached in 25% (2/8) of lung cysts. Average time to reach the target temperature inside the cyst was 6.3 min for the liver (range, 3-14 min) and 9.5 min for the lung (range, 3-19 min). During RF administration the internal temperature remained stable at target temperature in all treated cysts.

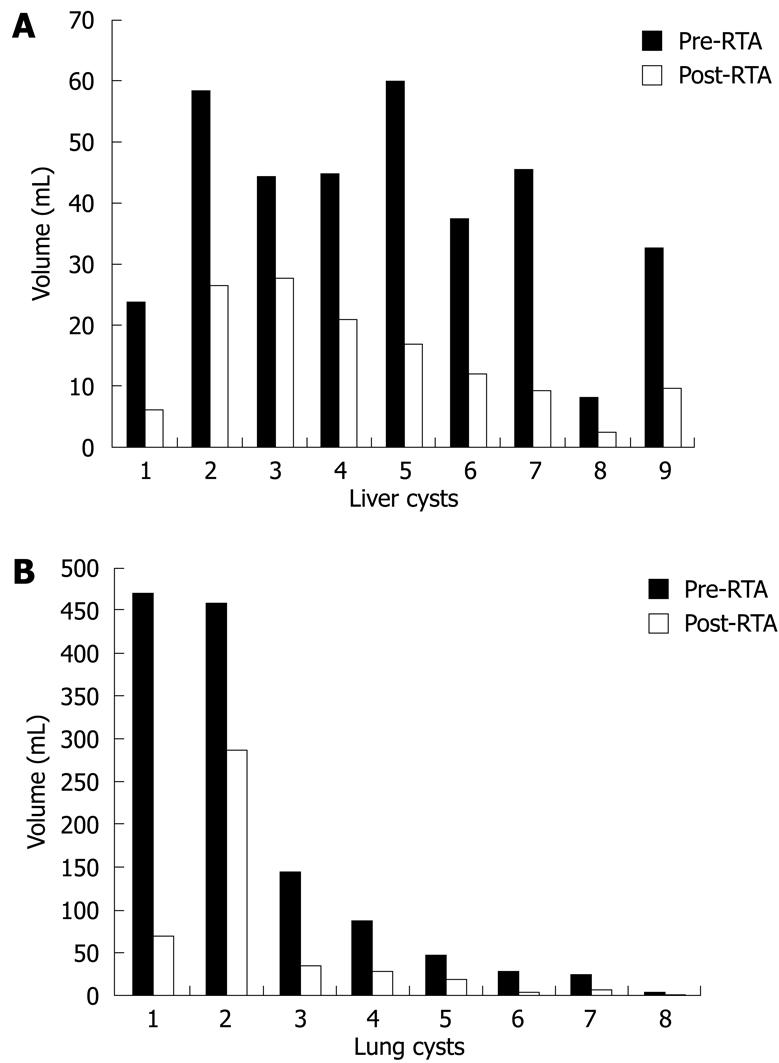

After RTA, 100% of the cysts had volume reduction. For the liver, the cyst volume average decreased from 40.5 mL before to 14.9 mL after RTA (P = 0.004). For the lung, the cyst mean volume decreased from 158.7 to 57.1 mL (P = 0.13). Hence, immediate reduction of mean volume for liver and lung cysts was 65% and 69%, respectively (Figure 2).

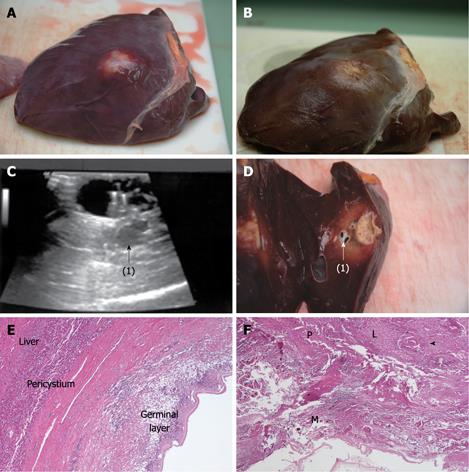

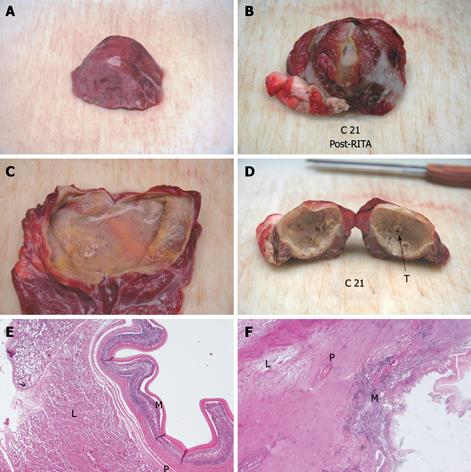

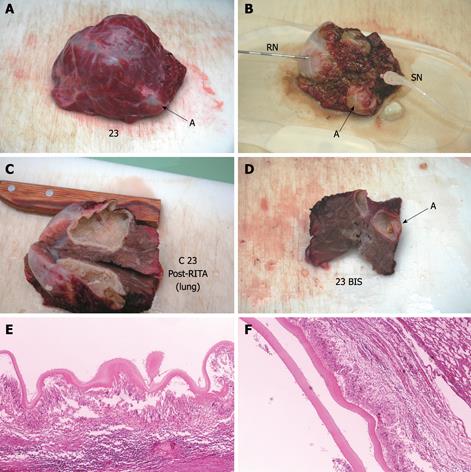

Compared with baseline, the endocyst remained attached to the pericystium after RTA in hepatic and lung cysts. We observed just a small and focal (i.e. few millimeters) de novo endocyst detachment in three hepatic cysts. Histology showed a 100% success rate in both hepatic (9/9) and lung cysts (8/8). A coagulative necrosis of the endocyst and the pericystium was observed, as well as a concentric area of host organ tissue necrosis, variable in size, with an average extension of 0.64 cm (range, 0-2 cm) for liver, and 1.57 cm (range, 0.8-2.5 cm) for lung (Figures 3,4,5,6). Possible correlation between cyst volume and size of pericyst necrosis was evaluated. For the liver, an inverse correlation of 68% was observed between pre-RTA volume and pericyst necrosis extension (P = 0.044). For lung cysts this correlation was 30% (P = 0.471). It is worth noting that within the necrotic area, parenchymal cells, blood vessels, bile ducts (liver) and bronchial walls (lung) were all necrotic in all treated cysts. Organ samples taken from areas far from the treated cysts showed normal histology in all cases.

Two cysts, hepatic and pulmonary, respectively, adjacent (< 1 cm) to the ones treated were killed despite no direct treatment (Figures 3 and 5). Another cyst, an external daughter lung cyst not directly treated, was partially alive at histology, though the procedure on the mother cyst was non-optimal because the cyst ruptured early.

Temperature curves detected inside and outside the cysts during the entire procedure had similar courses, but with clearly lower values in the host tissue near the cysts (data not shown). The highest temperature gradient (Tmax internal - Tmax external) ranged between 11.9°C and 58.3°C (mean, 38.0°C) in liver cysts and between 16.9°C and 38.7°C (mean, 27.7°C) in the lung. The external temperature peak was never above 70°C, and in 88% of the samples was below 55°C.

Our primary goal was to investigate whether RTA can kill Echinococcus granulosus cysts in explanted livers and lungs. We observed that RF (1) warmed the hydatid cyst fluid and caused endocyst necrosis in both hepatic and lung cysts in 100% of cases; (2) maintained endocyst attachment to the pericystium; (3) caused a layer of host tissue damage outside the cyst; (4) gave lower temperature values outside the cyst than inside it; and (5) resulted in a post-procedure volume reduction average of more than 65%.

From a review of the literature we found only two case reports on using RTA for treatment of cystic lesions in humans. No controlled study on RTA treatment of hydatid cysts is reported. Rhim et al[24] successfully treated a simple cyst of the liver, though this differs from the hydatid cyst from biological and pathological points of view. Brunetti et al[25] reported treatment with RTA on a single patient with cystic echinococcosis of the liver. However, here, the assessment of treatment efficacy was based solely on disappearance of scolices upon post-procedure microscopic examination of cyst fluid. This is not sufficient for assessing the definitive killing of the cyst if long term clinical follow-up is lacking, though the ideal procedure is microscopic verification of permanent damage to the germinal membrane, as mentioned by Brunetti et al[25] themselves in their comments on Khuroo’s paper[26]. In this regard, we would like to underscore that in our study a microscopic examination with methylene blue stain on cyst fluid collected through the sentinel needle just before, during, and soon after the RF administration was initially performed on a limited number of cysts, looking for scolices and their viability. This was discontinued in the study because of its total lack of sensitivity (no scolex was seen in the centrifuged fluid, even though they were present later at histology). Finally, Brunetti et al[25] in their case report say nothing of pressure stabilization to avoid cyst rupture.

Actually, in our pre-study sessions of treatment, all the cysts we treated invariably “exploded” a few minutes after the start of the procedure, independently of their baseline volume. That no longer happened after we started placing a “sentinel needle” inside the cyst. We also observed that ruptured cysts, despite reaching the target internal temperature faster, were still alive and often contained well preserved scolices on pathology examination. This suggests that RTA kills the parasite by using its own fluid, which assures homogeneous and sustained values of high temperature inside the whole cyst. If there is a rupture of the cyst and its fluid is released, RF causes only focal damage, probably where the needle tips are in contact with the cyst wall.

It has been demonstrated that during PAIR on cystic echinococcosis, the germinal membrane usually detaches entirely and collapses inside the cyst[3914–16]. This always occurs, by definition, during peri-cystectomy. Endocyst detachment can cause the appearance of biliary or bronchial fistulae inside the cyst cavity. This is more likely if a pre-existing virtual communication between the parasitic cyst and the biliary or bronchial tree is present[9102728]. The biliary fistula is one of the most frequent complications after surgery or percutaneous treatment of liver hydatid cysts[1529–31], though at lower rates after PAIR[332]. It often evolves into infected collection and abscess, thus increasing hospital length of stay, economic costs and patient discomfort[32]. The heat-related coagulative necrosis we obtained with RTA can explain both the killing effect on the parasite and also why the endocyst remained attached to the pericystium. Based on that, it seems reasonable to suppose a low (if not lack of) incidence of fistula occurrence after RTA in vivo. Furthermore, the layer of host tissue necrosis we observed outside the treated cysts, whether thinner or thicker, could further increase the killing effect (by stopping in vivo blood vessel supply) and decrease the incidence of post-procedure fistula occurrence (by causing bile duct or bronchial wall necrosis). This, of course, must still be proven by controlled in vivo studies. Nevertheless, an indication of this possibility emerged in a recently published case report by Thanos et al[33], who successfully treated a post-surgical biliocystic communication and cystocutaneous fistula with RF.

Based on our results we expect that in vivo blood flow would have no significant effect on the intra-cystic killing power of RTA. In fact, data on treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma and other hepatic tumors show how RTA can cause in vivo necrosis of vascularized nodules up to 5 cm in size[1920], and up to 8.5 cm in size if associated with occlusion of tumor blood supply[21]. This should occur even more on a hydatid cyst that has no internal blood flow (and therefore no internal heat sink effect), that is full of fluid and that has a relatively thick wall that creates a physical barrier from the outside, as also demonstrated by the gradient we calculated between the temperature inside the cysts and outside. In any case, only in vivo controlled studies can definitively answer this question.

Several studies report a volume reduction of the cyst of 65% or more after PAIR or pericystectomy, and such rates are described usually 6-19 mo after the treatment[16313435]. In our study, compared with baseline, we observed this level of volume reduction immediately after treatment. This is probably due to necrosis and dehydration of the cyst wall and the surrounding host tissues (Figures 5 and 6). The volume decrease after RTA and correlation of cyst volume with extension of pericyst necrosis were significant for the liver but not for the lung. This is probably due to different tissue characteristics (liver is solid, while lung has some air inside); to the small number of cases analyzed; and, lastly, to the fact that the lung cysts provided were larger and mainly exophytic compared with the hepatic cysts. An optimal statistical investigation of such correlations would require larger numbers.

With respect to our goals, we believe the results of our pilot study are very interesting, particularly the 100% success rate we observed despite different baseline cyst volumes and types of organs treated.

Potential advantages expected with in vivo RTA on cystic echinococcosis as follows: (1) While PAIR sometimes requires more sections to assure definitive killing of the cyst, RTA can kill a hydatid cyst in a single section, since the entire cyst wall is made necrotic by a heat-related mechanism; (2) Given that RTA avoids the use of chemical media there is no risk of chemical cholangitis related to its accidental passing into the biliary tree. Hence, pre-existence of cysto-biliary communication is no longer a contraindication to percutaneous treatment; (3) Compared with PAIR or surgery, persistence of endocyst attachment to pericystium in a high percentage of cases should help avoid or greatly decrease post-RTA fistula occurrence, and consequent overlapping complications.

The results, and the experimental hypothesis raised by our study, must be confirmed by in vivo study.

Treatment of cystic echinococcosis is surgery or percutaneous aspiration, injection and reaspiration (PAIR) using hypertonic saline or ethanol, and it is aimed to cause permanent damage to the endocyst. Surgery and PAIR can result in biliary or bronchial fistulae, prompted by endocyst detachment; chemical cholangitis or pneumonia, due to passing of hypertonic saline or ethanol into the biliary or bronchial tree; and infection or abscess on residual cyst cavity. Radiofrequency thermal ablation (RTA) is currently used for treatment of neoplasms, primarily hepatocellular carcinoma.

Features of an ideal therapy for hydatid cysts should include the following: (1) certainty of killing the parasite; (2) avoidance of post-procedure fistulae and consequent overlapping complications; (3) mini-invasive approach. The authors experimented with the use of RTA trusting in its heat-related killing power as well as on the possibility that, after heat-related coagulative necrosis of cyst wall, the parasitic endocyst could have remained attached to the pericystium. This approach is unlike surgery or PAIR, which invariably cause endocyst detachment.

The research showed that radiofrequency is able to warm and irreversibly damage hydatid cysts in a single section, since the entire cyst wall is made necrotic by a heat-related mechanism. Avoiding the use of chemical media, there is no risk of chemical cholangitis. Unlike PAIR, the existence of cysto-biliary communication would no longer be a contraindication to percutaneous treatment of the hydatid cyst. The persistence of endocyst attachment to pericystium should help avoid or greatly decrease post-RTA fistula occurrence and consequent overlapping complications.

This pilot study suggests that a new therapeutic approach in treatment of hydatid cyst is possible and, indeed, very effective. The ex vivo model is expected to be predictive of what would be the in vivo effect of RTA, since cystic lesions have no internal blood vessels. In vivo blood flow would not have a significant impact, particularly in view of the fact that HCCs of several cm can be currently ablated with RTA despite being vascularized (heat sink effect), and that RTA power is increased by occlusion of tumor blood supply. The study also seems to suggest that RTA could potentially be used to attempt treatment of other types of cystic lesions (symptomatic treatment in polycystic disease, cystic neoplasms, pancreatic pseudocysts, etc).

Cystic echinococcosis is a helminthic zoonosis that can affect human beings, most frequently involving the liver or the lungs, where it causes expansive cystic lesions. Endocyst or prolifera membrane is the thin, delicate, and translucid inner membrane that produces the cyst fluid and generates new larval elements able to expand the infestation.

This is an ex vivo pilot study on RFA in cystic echinococcosis in a relatively small animal sample size. The authors report 100% success rate in treating cysts and several innovative technical aspects. Results and literature data reported in the paper discussion suggest that this technique is very promising.

| 1. | Sayek I, Tirnaksiz MB, Dogan R. Cystic hydatid disease: current trends in diagnosis and management. Surg Today. 2004;34:987-996. |

| 2. | Chin J. Control of communicable disease manual. Washington: American Public Health Association 2000; 176-179. |

| 3. | Smego RA Jr, Sebanego P. Treatment options for hepatic cystic echinococcosis. Int J Infect Dis. 2005;9:69-76. |

| 4. | Ulkü R, Yilmaz HG, Onat S, Ozçelik C. Surgical treatment of pulmonary hydatid cysts: report of 139 cases. Int Surg. 2006;91:77-81. |

| 5. | Guidelines for treatment of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in humans. WHO Informal Working Group on Echinococcosis. Bull World Health Organ. 1996;74:231-242. |

| 6. | Nasseri Moghaddam S, Abrishami A, Malekzadeh R. Percutaneous needle aspiration, injection, and reaspiration with or without benzimidazole coverage for uncomplicated hepatic hydatid cysts. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;CD003623. |

| 7. | Dervenis C, Delis S, Avgerinos C, Madariaga J, Milicevic M. Changing concepts in the management of liver hydatid disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:869-877. |

| 8. | Fìlice C, Brunetti E, Bruno R, Crippa FG. Percutaneous drainage of echinococcal cysts (PAIR--puncture, aspiration, injection, reaspiration): results of a worldwide survey for assessment of its safety and efficacy. WHO-Informal Working Group on Echinococcosis-Pair Network. Gut. 2000;47:156-157. |

| 9. | Mawhorter S, Temeck B, Chang R, Pass H, Nash T. Nonsurgical therapy for pulmonary hydatid cyst disease. Chest. 1997;112:1432-1436. |

| 10. | Akhan O, Ozmen MN, Dinçer A, Göçmen A, Kalyoncu F. Percutaneous treatment of pulmonary hydatid cysts. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1994;17:271-275. |

| 11. | Horton RJ. Albendazole in treatment of human cystic echinococcosis: 12 years of experience. Acta Trop. 1997;64:79-93. |

| 12. | Franchi C, Di Vico B, Teggi A. Long-term evaluation of patients with hydatidosis treated with benzimidazole carbamates. Clin Infect Dis. 1999;29:304-309. |

| 13. | Brehm K, Kern P, Hubert K, Frosch M. Echinococcosis from every angle. Parasitol Today. 1999;15:351-352. |

| 14. | Khuroo MS, Zargar SA, Mahajan R. Echinococcus granulosus cysts in the liver: management with percutaneous drainage. Radiology. 1991;180:141-145. |

| 15. | Ustünsöz B, Akhan O, Kamiloğlu MA, Somuncu I, Uğurel MS, Cetiner S. Percutaneous treatment of hydatid cysts of the liver: long-term results. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;172:91-96. |

| 16. | Khuroo MS, Wani NA, Javid G, Khan BA, Yattoo GN, Shah AH, Jeelani SG. Percutaneous drainage compared with surgery for hepatic hydatid cysts. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:881-887. |

| 17. | Castellano G, Moreno-Sanchez D, Gutierrez J, Moreno-Gonzalez E, Colina F, Solis-Herruzo JA. Caustic sclerosing cholangitis. Report of four cases and a cumulative review of the literature. Hepatogastroenterology. 1994;41:458-470. |

| 18. | Tsimoyiannis EC, Grantzis E, Moutesidou K, Lekkas ET. Secondary sclerosing cholangitis: after injection of formaldehyde into hydatid cysts in the liver. Eur J Surg. 1995;161:299-300. |

| 19. | Delis S, Bramis I, Triantopoulou C, Madariaga J, Dervenis C. The imprint of radiofrequency in the management of hepatocellular carcinoma. HPB (Oxford). 2006;8:255-263. |

| 20. | Geyik S, Akhan O, Abbasoğlu O, Akinci D, Ozkan OS, Hamaloğlu E, Ozmen M. Radiofrequency ablation of unresectable hepatic tumors. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2006;12:195-200. |

| 21. | Rossi S, Garbagnati F, Lencioni R, Allgaier HP, Marchianò A, Fornari F, Quaretti P, Tolla GD, Ambrosi C, Mazzaferro V. Percutaneous radio-frequency thermal ablation of nonresectable hepatocellular carcinoma after occlusion of tumor blood supply. Radiology. 2000;217:119-126. |

| 22. | Garippa G. Updates on cystic echinococcosis (CE) in Italy. Parassitologia. 2006;48:57-59. |

| 23. | Giannetto S, Poglayen G, Brianti E, Sorgi C, Gaglio G, Canu S, Virga A. An epidemiological updating on cystic echinococcosis in cattle and sheep in Sicily, Italy. Parassitologia. 2004;46:423-424. |

| 24. | Rhim H, Kim YS, Heo JN, Koh BH, Cho OK, Kim Y, Seo HS. Radiofrequency thermal ablation of hepatic cyst. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004;15:95-96. |

| 25. | Brunetti E, Filice C. Radiofrequency thermal ablation of echinococcal liver cysts. Lancet. 2001;358:1464. |

| 26. | Schipper HG, Kager PA. Percutaneous drainage of hydatid cysts. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:391; author reply 392-393. |

| 28. | al Karawi MA, el-Shiekh Mohamed AR, Yasawy MI. Advances in diagnosis and management of hydatid disease. Hepatogastroenterology. 1990;37:327-331. |

| 29. | Akhan O, Ozmen MN, Dinçer A, Sayek I, Göçmen A. Liver hydatid disease: long-term results of percutaneous treatment. Radiology. 1996;198:259-264. |

| 30. | Men S, Hekimoğlu B, Yücesoy C, Arda IS, Baran I. Percutaneous treatment of hepatic hydatid cysts: an alternative to surgery. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;172:83-89. |

| 31. | Schipper HG, Laméris JS, van Delden OM, Rauws EA, Kager PA. Percutaneous evacuation (PEVAC) of multivesicular echinococcal cysts with or without cystobiliary fistulas which contain non-drainable material: first results of a modified PAIR method. Gut. 2002;50:718-723. |

| 32. | Yagci G, Ustunsoz B, Kaymakcioglu N, Bozlar U, Gorgulu S, Simsek A, Akdeniz A, Cetiner S, Tufan T. Results of surgical, laparoscopic, and percutaneous treatment for hydatid disease of the liver: 10 years experience with 355 patients. World J Surg. 2005;29:1670-1679. |

| 33. | Thanos L, Mylona S, Brontzakis P, Ptohis N, Karaliotas K. A complicated postsurgical echinococcal cyst treated with radiofrequency ablation. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2008;31:215-218. |

| 34. | Bozkurt B, Soran A, Karabeyoğlu M, Unal B, Coşkun F, Cengiz O. Follow-up problems and changes in obliteration of the residual cystic cavity after treatment for hepatic hydatidosis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2003;10:441-445. |

| 35. | Smego RA Jr, Bhatti S, Khaliq AA, Beg MA. Percutaneous aspiration-injection-reaspiration drainage plus albendazole or mebendazole for hepatic cystic echinococcosis: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:1073-1083. |