Published online Aug 7, 2007. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i29.3996

Revised: March 10, 2007

Accepted: March 26, 2007

Published online: August 7, 2007

AIM: To examine the utility of Six Minute Walk Test (6MWT) in patients with chronic liver disease (CLD).

METHODS: Two hundred and fifty subjects between the ages of 18 and 80 (mean 47) years performed 6MWT and the Six Minute Walk Distance (6MWD) was measured.

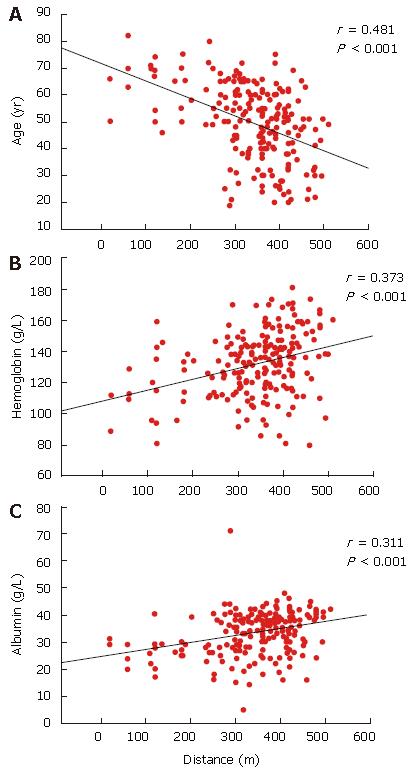

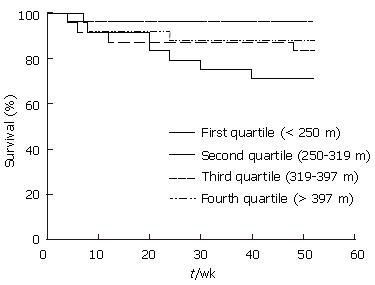

RESULTS: The subjects were categorized into four groups. Group A (n = 45) healthy subjects (control); group B (n = 49) chronic hepatitis B patients; group C (n = 54) chronic hepatitis C patients; group D (n = 98) liver cirrhosis patients. The four groups differed in terms of 6MWDs (P < 0.001). The longest distance walked was 421 ± 47 m by group A, then group B (390 ± 53 m), group C (357 ± 72 m) and group D (306 ± 111 m). The 6MWD correlated with age (r = -0.482, P < 0.01), hemoglobin (r = +0.373, P < 0.001) and albumin (r = +0.311, P < 0.001) levels. The Child-Pugh classification was negatively correlated with the 6MWD in cirrhosis (group D) patients (r = -0.328, P < 0.01). At the end of a 12 mo follow-up period, 15 of the 98 cirrhosis patients had died from disease complications. The 6MWD for the surviving cirrhotic patients was longer than for non-survivors (317 ± 101 vs 245 ± 145 m, P = 0.021; 95% CI 11-132). The 6MWD was found to be an independent predictor of survival (P = 0.024).

CONCLUSION: 6MWT is a useful tool for assessing physical function in CLD patients. We suggest that 6MWD may serve as a prognostic indicator in patients with liver cirrhosis.

- Citation: Alameri HF, Sanai FM, Al Dukhayil M, Azzam NA, Al-Swat KA, Hersi AS, Abdo AA. Six Minute Walk Test to assess functional capacity in chronic liver disease patients. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13(29): 3996-4001

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v13/i29/3996.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i29.3996

The assessment of quality of life has a significant impact on the management of chronic liver disease (CLD) patients. Several studies have shown that CLD leads to a reduction in health-related quality of life, particularly in terms of functional capacity[1-5]. Most such studies examining functional capacity involve questionnaires such as the Medical Outcome Study Short Form Questionnaire (SF-36) and the Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire (CLDQ). These questionnaires are exclusively research tools, and the recording of information from such questionnaires can be difficult to incorporate into daily clinical practice. While exercise tests can also be used to measure functional capacity, the sophisticated techniques and complex interpretation involved usually mean that these tests can only be conducted in suitably equipped laboratories with experienced personnel, which in turn may only be available in specialized centers.

The Six Minute Walk Test (6MWT) is an easy and inexpensive sub-maximal exercise test and has been shown to have good reliability when used to assess functional capacity. The 6MWT has been used in addition and sometimes as an alternative to, other diagnostic tools in patients with chronic cardiac, pulmonary, neuromuscular or renal diseases[6-11]. Roul and coworkers reported that the distance walked in six minutes had a sensitivity of 89% and specificity of 60% for predicting the prognosis and disease outcomes in patients with heart failure[12]. Another study showed that the Six Minute Walk Distance (6MWD) was an independent predictor of mortality in patients with chronic obstructive lung diseases[13]. A study exploring functional performance in 38 end-stage liver disease patients found that the 6MWD correlated with muscle strength and exercise capacity as measured using cardiopulmonary exercise tests. The same study reported that the 6MWD strongly correlated with all physical performance tests at three, six and 12 mo follow-up times after orthotopic liver transplantation[14].

The present prospective study examined the use of the 6MWT for assessing the functional capacity of chronic liver disease patients. The study compared the distances walked in six minutes by healthy subjects and patients with different stages of liver disease, and investigated correlations between the 6MWD and other clinical and biochemical disease markers.

The study enrolled consecutive patients aged between 18 and 80 years with chronic liver disease attending the hepatology outpatient clinics at King Khalid University Hospital (KKUH) and Riyadh Military Hospital over a 12 mo period (from January to December 2005). All subjects gave formal consent and the study was approved by the departmental Ethics Committee. Study subjects were categorized into four groups. Group A subjects were sequentially selected healthy volunteers with no clinical history of liver diseases were recruited as controls. Group B subjects were patients with the following profile: hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positive as determined by a commercial ELISA kit (Diagnostics Pasteur, Marnes la Coquette, France), hepatitis B DNA positive by a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) based assay (COBAS Amplicor, HBV monitor test, Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland) with a lower limit of detection of 200 copies/mL, and with (1) either normal or raised alanine transaminase (ALT) levels (determined on at least two occasions separated by at least 3 mo), (2) normal serum bilirubin, albumin and International Normalized Ratio (INR), (3) normal complete blood count (CBC) or (4) normal abdominal ultrasound (US) without features of liver cirrhosis or portal hypertension. Group C subjects were patients with the following profile: newly diagnosed with hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection (i.e.anti-HCV antibody, Ortho HCV ELISA, Ortho Diagnostic Systems, Inc., Raritan, New Jersey; RIBA HCV, Chiron Corp., Emeryville, California) and HCV RNA positive (COBAS Amplicor, HCV monitor test, Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland) with a lower limit of detection of 50 IU/L, and raised ALT levels. Patients were excluded from groups B and C if there was any abnormality in the CBC or any signs of cirrhosis or portal hypertension on abdominal US. Group D subjects were patients with liver cirrhosis defined by any four of the following features of cirrhosis: (1) platelet count < 100 × 109/L, (2) evidence of esophageal varices on endoscopy, (3) ultrasonographic features consistent with cirrhosis, (4) albumin level less than 30 g/L, (5) INR more than 1.4 and (6) bilirubin level more than 30 μmol/L. Patients were also included in this group if there was histological evidence of liver cirrhosis regardless of the above criteria.

Patients who were HBsAg or anti-HCV positive for a period exceeding six months and who had not received any antiviral therapy in the preceding six months were included in the study. All participants had screening abdominal ultrasonography (US) at the time of recruitment into the study. The US were performed and interpreted by trained radiographers according to a standardized protocol, and the records reviewed by the investigators. Cirrhosis was diagnosed ultrasonographically based on the appearance of the liver surface, liver parenchymal texture, portal vein size, splenic size, presence of ascites and varicose veins in the portal and perisplenic area.

Study exclusion criteria included: (1) HCV/HBV coinfection; (2) identifiable other causes of chronic liver disease defined as (high serum iron and ferritin, abnormal serum ceruloplasmin, history of significant alcohol consumption, antinuclear antibody > 1:320, antismooth muscle antibody > 1:320, antimitochondrial antibody > 1:40); (3) history of hepatotoxic medications in the preceding three months of presentation; (4) history of antiviral therapy in the last six months. All subjects were assessed initially by a senior physician and any patients with clinical evidence of cardiopulmonary, neuromuscular or rheumatological diseases was excluded.

To determine hemoglobin, platelet, liver enzymes, bilirubin, albumin and creatinine levels and coagulation profiles, blood samples were obtained from all patients preferably at the time of the 6MWT. Patients with liver cirrhosis were further classified as stage A, B or C according to the modified Child-Pugh classification (CP)[15]. Results of all abnormal tests were provided to patients or their immediate relatives, as was deemed appropriate.

The 6MWT was conducted according to American Thoracic Society (ATS) guidelines and supervised by qualified technicians[16]. The technicians were blinded to the grouping to which the patients belonged. In brief, the patient was instructed to walk at his or her own pace along a straight, flat 30 m hallway marked at one meter intervals. Heart rate, blood pressure, oxygen saturation and Borg score (based on an exertion scale where 0 = no exertion and 10 = very severe exertion) were measured at the start (0 min) and at the end (six minutes) of the walk test. Patients were asked to cover as much ground as possible in six minutes but allowed to stop if there were symptoms of dyspnea or leg pain. The distance in meters was recorded at the end of the six minutes (i.e., the 6MWD).

All data are expressed as mean ± SD. Comparisons between two groups were made using unpaired Student’s T-tests. Comparisons between four groups were made using one-way ANOVA followed by the Scheffe post hoc multiple comparison test. Correlations between the 6MWD and other variables were determined using Pearson correlation coefficients analysis. Multiple regression analysis was used to identify independent relationships between the 6MWD and demographic variables. In patients with liver cirrhosis, both Cox’s proportional hazard regression and Kaplan-Meier analyses were used to determine whether the 6MWD had an impact on survival. Cox’s proportional hazard regression model was used to estimate the relative risk of the following variables on survival: age, male gender, CP score, the 6MWD, hemoglobin, albumin, alkaline phosphatase and creatinine levels, and prothrombin time. Survival was also analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method and survival curves were compared according to four groups of walked distance using log rank tests. A P value < 0.05 was considered to indicate a significant difference. All data were processed using SPSS 13.0 for Windows.

The demographic features, laboratory data and the 6MWD for the four groups are summarized in Table 1. There were a total of 250 subjects in the study (60% male): 45 (18% of the total number of subjects) in group A, 49 (19.6%) in group B, 58 (23.2%) in group C and 98 (39.2%) in group D. Both group A and B were similar in terms of age, height and weight, while the group C mean age was greater than that of group A and B. Group B and C did not differ in terms of laboratory results. The mean age for group D was greater than that of other groups. Compared to group B and C, group D subjects had lower hemoglobin levels, higher liver enzyme levels, hypoalbuminemia, higher bilirubin levels and a higher coagulation time.

| Variable | Group A | Group B | Group C | Group D | |

| (n = 45) | (n = 48) | (n = 58) | (n = 98) | ||

| Age (yr) | 35 ± 9 | 38 ± 12 | 48 ± 12 | 57 ± 12 | |

| Gender (M:F) | 22/23 | 22/27 | 42/16 | 64/34 | |

| BMI | 28.0 ± 6.3 | 33.3 ± 20.6 | 30.0 ± 6.4 | 26.9 ± 5.3 | |

| HR/min | Baseline | - | 78 ± 12 | 85 ± 14 | 84 ± 17 |

| End | - | 86 ± 13 | 94 ± 17 | 92 ± 19 | |

| O2 % | Baseline | - | 98.1 ± 1.0 | 96.7 ± 9.3 | 97.8 ± 1.75 |

| End | - | 98.2 ± 0.76 | 98.1 ± 1.1 | 97.1 ± 2.8 | |

| BS | Baseline | - | 0.11 ± 0.45 | 0.07 ± 0.24 | 0.66 ± 1.34 |

| End | - | 0.53 ± 0.73 | 0.98 ± 1.34 | 1.68 ± 2.00 | |

| 6MWD (m) | 421 ± 47 | 390 ± 53 | 357 ± 72 | 306 ± 111 | |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | - | 128.7 ± 44.1 | 136.2 ± 20.3 | 94.9 ± 54.6 | |

| Albumin (g/L) | - | 37.9 ± 6.1 | 37.6 ± 6.3 | 28.3 ± 6.8 | |

| ALT (U/L) | - | 128.5 ± 232.2 | 89.7 ± 54.2 | 86.2 ± 63.1 | |

| AST (U/L) | - | 55.8 ± 70.2 | 56.4 ± 34.0 | 94.8 ± 76.9 | |

| GGT (U/L) | - | 47.7 ± 50.0 | 101.6 ± 83.3 | 164.6 ± 225.2 | |

| ALP (U/L) | - | 96.7 ± 36.4 | 102.8 ± 42.1 | 180.7 ± 129.4 | |

| Bilirubin (μmol/L) | - | 11.1 ± 6.3 | 14.9 ± 12.8 | 44.0 ± 58.9 | |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | - | 70.3 ± 21.4 | 68.0 ± 16.6 | 86.8 ± 39.1 | |

The 6MWD differed between the four groups. The 6MWD for group B (389 ± 53 m) was shorter than for group A (421 ± 47 m) (P = 0.02; 95% CI 2-43). The 6MWDs for both group A and B were longer than for group C (357 ± 71 m) (P = 0.01; 95% CI 39-88 and P = 0.01; 95% CI 7-56 respectively). Group D (306 ± 111 m) had a shorter 6MWD than any of group A (P = 0.001; 95% CI 105-124), B (P = 0.001; 95% CI 72-93) or C (P = 0.001; 95% CI 36-65).

The 6MWD was found to be inversely correlated with age (r = -0.482, P < 0.001, 95% CI 3.8-2.4)) and Borg scores at the beginning (r = -0.518, P < 0.001; 95% CI -59 to -37) and end (r = -0.581, P = 0.001; 95% CI -40 to -27) of the test. The 6MWD was found to be positively correlated with height (r = 0.281, P = 0.01; 95% CI 1.3-3.2), hemoglobin level (r = 0.373, P = 0.001; 95% CI 0.48-0.99) and albumin level (r = 0.311, P = 0.001; 95% CI 2.1-5.3) (Figure 1). Linear regression analysis showed that the best demographic and laboratory predictors for the 6MWD in the disease groups were age, Borg score and hemoglobin level (P = 0.001 and r2 value ranging between 0.336 and 0.526).

Of the 98 liver cirrhosis (group D) patients, 33 were CP class A, 39 class B and 27 class C. The 6MWD for CP class A patients was 356 ± 84 m, which was longer than the distance walked by either CP class B (296 ± 93 m; P = 0.005) or CP class C (262 ± 130 m; P = 0.003) patients. There was no significant difference between CP class B and CP class C patients in terms of the distance walked. The 6MWD was negatively correlated with CP classification (r = -0.328, P≤ 0.001; 95% CI -74 to -19), and positively correlated with the level of oxygen saturation at the beginning and end of the test (r = 0.402, P < 0.0001 and r = 0.283, P = 0.018, respectively).

Patients with liver cirrhosis were followed from the time of 6MWT until the end of the study period or death. During a mean follow-up period of 42 ± 13 (range, 4 to 52) wk, fifteen (15.3%) of the 98 cirrhosis patients (group D) died from disease complications. The 6MWD for the surviving cirrhotic patients was longer than that for non-survivors (317 ± 101 vs 245 ± 145 m, P = 0.021; 95% CI 11-132). In addition, the non-survivors had a higher mean CP score and higher alkaline phosphatase and creatinine levels, and lower albumin and hemoglobin levels (Table 2).

| Variable | Non-survivors (n = 15) | Survivors (n = 83) | P | |

| Age (yr) | 61 ± 10 | 55 ± 11 | 0.064 | |

| CP score | 10.0 ± 2.3 | 8.5 ± 2.2a | 0.016 | |

| 6MWD (m) | 245 ± 145 | 317 ± 101a | 0.021 | |

| O2% | Baseline | 97.3 ± 1.7 | 97.9 ± 1.5 | 0.21 |

| End | 97.4 ± 3.0 | 97.2 ± 1.6 | 0.64 | |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 114.7 ± 14.7 | 127.6 ± 17.7b | 0.009 | |

| Prothrombin time (s) | 16.1 ± 5.6 | 16.5 ± 4.5 | 0.82 | |

| ALT (U/L) | 90.5 ± 82.7 | 85.4 ± 59.5 | 0.77 | |

| AST (U/L) | 107.1 ± 62.6 | 92.3 ± 79.4 | 0.50 | |

| ALP (U/L) | 242.2 ± 141.8 | 169.5 ± 124.7 | 0.45 | |

| Albumin (g/L) | 24.2 ± 5.6 | 29.0 ± 6.6a | 0.011 | |

| Bilirubin (μmol/L) | 67.4 ± 65.1 | 40.1 ± 56.9 | 0.098 | |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | 114.4 ± 86.0 | 81.7 ± 18.0b | 0.002 | |

The effect of a range of variables on survival was determined using Cox regression analysis (Table 3). Univariate analysis showed anemia, hypoalbuminemia, high CP scores, a low 6MWD and elevated alkaline phosphatase and creatinine levels were associated with shorter survival. Multivariate analysis showed that a low 6MWD (P = 0.024), and elevated alkaline phosphatase (P = 0.027) and creatinine (P < 0.0001) levels were associated with shorter survival in cirrhosis patients.

| Variable | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P | |

| UV | CP Score | 1.349 (1.062-1.713) | 0.014 |

| UV | 6MWD | 0.995 (0.991-0.999) | 0.027 |

| UV | Albumin | 0.901 (0.829-0.978) | 0.013 |

| UV | Hemoglobin | 0.966 (0.941-0.992) | 0.012 |

| UV | ALP | 1.003 (1.000-1.005) | 0.042 |

| UV | Creatinine | 1.016 (1.007-1.024) | < 0.0001 |

| MV | 6MWD | 0.994 (0.989-0.998) | 0.024 |

| MV | ALP | 1.003 (1.000-1.006) | 0.027 |

| MV | Creatinine | 1.018 (1.009-1.027) | < 0.0001 |

Kaplan-Meier survival curve analysis was used to assess cirrhosis patients in terms of the distance walked (Figure 2). Patients were categorized according to the distance walked into four groups; first quartile (6MWD < 250 m), second quartile (250 m ≤ 6MWD < 319 m), third quartile (319 m ≤ 6MWD < 397 m) and fourth quartile (6MWD ≥ 397 m). Log rank testing showed that those who walked less than 250 m had a shorter survival (P = 0.021) compared to the other groups, and suggested that lower survival was linked to a lesser 6MWD.

The present study showed that the 6MWT can be used to determine the functional capacity of CLD patients. The distance walked by CLD patients was found to be lower than that walked by healthy subjects. Furthermore, in terms of different chronic liver diseases, the study found that the 6MWD was lower for cirrhosis patients compared to patients with chronic hepatitis B or C infections.

The distance walked by hepatitis B patients was found to be less than that walked by matched healthy individuals. This was found to be the case even for the group of hepatitis B patients with normal liver enzymes results (i.e., inactive carriers). Previous studies dealing with the effect of hepatitis B infection on physical function have provided contradictory findings. While one study found that 60% of hepatitis B carrier status patients reported a decrease in physical and psychological health as measured using a questionnaire[1], another study found that this was not the case[2]. To our knowledge, the present study is the first to use an exercise test to objectively measure physical capacity in non-cirrhotic hepatitis B patients, rather than a questionnaire.

The current study also found that the distance walked by hepatitis C patients was less than that walked by hepatitis B patients or control subjects. Previously, physical performance in hepatitis C patients was mostly explored using quality-of-life questionnaires. An earlier study examining physical function using the SF-36 questionnaire found that function was lower in patients with chronic hepatitis C infection compared to control subjects or patients with hepatitis B, and that this decrease was unrelated to the extent of liver injury according to liver biopsy and liver enzyme tests[2]. The study concluded that the physical impairment may be related to factors other than liver damage. In the present study, hepatitis C patients walked significantly shorter distances in six minutes than hepatitis B patients, even though both groups were similar in terms of liver enzyme test results, hemoglobin levels, albumin levels and coagulation profiles.

Other studies have reported that there are several potential factors that can contribute to the physical function limitations in cirrhosis patients, including muscle strength, deconditioning, fatigue and neuropsychiatric factors in addition to hepatopulmonary syndrome and cirrhotic cardiomyopathy[10,17,18]. In the present study, liver cirrhosis patients had the lowest 6MWD of the four groups tested, and the 6MWD was found to correlate with the severity of cirrhosis as measured using the Child-Pugh classification. Consistent with these findings, several studies showed a moderate-to-severe impairment in exercise capacity in cirrhosis patients as measured by cardiopulmonary exercise testing[17,19-22]. In one such study, the 6MWD correlated with the maximum oxygen uptake (VO2 max) as measured using a cycle ergometer in pre-liver transplantation patients at different stages of cirrhosis, and that correlation remained over a one year follow-up period after transplantation[14].

In the present study, the 6MWD was negatively cor-related with patient age, and age was found to be an independent predictor of the 6MWD. This finding is consistent with various studies of both healthy subjects and chronic disease patients[23-25]. The current study also found that the 6MWD was positively correlated with hemoglobin and albumin levels, but did not correlate with liver enzyme levels. This finding is consistent with previous reports showing that for severe heart failure patients, anemia was associated with poor physical function, while increasing hemoglobin levels were correlated with improved exercise capacity as measured in cardiopulmonary exercise tests[26,27]. Previous studies also found that the severity of physical limitation in relation to liver biochemical testing was more evident in liver cirrhosis patients compared to those with other chronic liver diseases[21,28,29].

Previous reports showed that several factors correlate with mortality in patients with liver cirrhosis. Multivariate analysis in the present study found that the 6MWD was linked to mortality. In our cohort, walking less than 250 m was associated with decreased survival in patients with liver cirrhosis. Consistent with this finding, Bowen et al[30], reported that the distance walked was better associated with survival than other signs of disease severity like pulmonary function results, arterial blood gas results, age and comorbid conditions in patients with advance lung diseases. Paciocco et al[31] found that there was an 18% reduction in mortality with each 50 m increase in walked distance in pulmonary hypertension patients, with significant mortality being reported in patients walking less than 300 m. To our knowledge, the present study is the first to investigate the 6MWD as a predictor of survival in patients with non-cardiopulmonary disease. Thus, the 6MWD may serve as an additional prognostic marker in liver cirrhosis patients.

Our study has a few potential limitations. One such limitation is that the control group subjects were mostly recruited from within the institute (including hospital employees and medical students), and may therefore consist of more highly educated individuals with a higher socio-economic status compared to the CLD groups, which are more likely to come from the broader general population.

Another limitation is the possibility that the distance walked was not assessed accurately because the 6MWT was performed just once. However, other investigators have shown that in patients with chronic renal failure, the improvement in the distance walked was only 3.7% when the test was repeated after 48 h, suggesting that the 6MWT may be more reproducible in non-cardiopulmonary disease patients[32].

Finally, the present 6MWD data were not compared with data obtained from other physical function assessments such as cardiopulmonary exercise tests. While cycling ergometer testing was not undertaken due to our limited experience with this assessment tool in our community, we are currently examining correlations between the 6MWD data and quality-of-life questionnaire responses in CLD patients.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that the 6MWD correlated with the type of liver diseases, and it was an independent predictor of survival in liver cirrhosis patients. The utility of 6MWD should be further explored to evaluate the change of distance walked over time or in response to therapeutic measures in patients with CLD.

| 1. | Lok AS, van Leeuwen DJ, Thomas HC, Sherlock S. Psychosocial impact of chronic infection with hepatitis B virus on British patients. Genitourin Med. 1985;61:279-282. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Foster GR, Goldin RD, Thomas HC. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection causes a significant reduction in quality of life in the absence of cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1998;27:209-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 378] [Cited by in RCA: 377] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bianchi G, Loguercio C, Sgarbi D, Abbiati R, Chen CH, Di Pierro M, Disalvo D, Natale S, Marchesini G. Reduced quality of life in patients with chronic hepatitis C: effects of interferon treatment. Dig Liver Dis. 2000;32:398-405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Marchesini G, Bianchi G, Amodio P, Salerno F, Merli M, Panella C, Loguercio C, Apolone G, Niero M, Abbiati R. Factors associated with poor health-related quality of life of patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:170-178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 348] [Cited by in RCA: 363] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sainz-Barriga M, Baccarani U, Scudeller L, Risaliti A, Toniutto PL, Costa MG, Ballestrieri M, Adani GL, Lorenzin D, Bresadola V. Quality-of-life assessment before and after liver transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:2601-2614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Butland RJ, Pang J, Gross ER, Woodcock AA, Geddes DM. Two-, six-, and 12-minute walking tests in respiratory disease. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1982;284:1607-1608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1052] [Cited by in RCA: 1118] [Article Influence: 25.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Guyatt GH, Sullivan MJ, Thompson PJ, Fallen EL, Pugsley SO, Taylor DW, Berman LB. The 6-minute walk: a new measure of exercise capacity in patients with chronic heart failure. Can Med Assoc J. 1985;132:919-923. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Langenfeld H, Schneider B, Grimm W, Beer M, Knoche M, Riegger G, Kochsiek K. The six-minute walk--an adequate exercise test for pacemaker patients? Pacing Clin Electrophysiol. 1990;13:1761-1765. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Montgomery PS, Gardner AW. The clinical utility of a six-minute walk test in peripheral arterial occlusive disease patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:706-711. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Deboeck G, Niset G, Vachiery JL, Moraine JJ, Naeije R. Physiological response to the six-minute walk test in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:667-672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Savci S, Inal-Ince D, Arikan H, Guclu-Gunduz A, Cetisli-Korkmaz N, Armutlu K, Karabudak R. Six-minute walk distance as a measure of functional exercise capacity in multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2005;27:1365-1371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 117] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Roul G, Germain P, Bareiss P. Does the 6-minute walk test predict the prognosis in patients with NYHA class II or III chronic heart failure? Am Heart J. 1998;136:449-457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Celli BR, Cote CG, Marin JM, Casanova C, Montes de Oca M, Mendez RA, Pinto Plata V, Cabral HJ. The body-mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity index in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1005-1012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2409] [Cited by in RCA: 2593] [Article Influence: 117.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Beyer N, Aadahl M, Strange B, Kirkegaard P, Hansen BA, Mohr T, Kjaer M. Improved physical performance after orthotopic liver transplantation. Liver Transpl Surg. 1999;5:301-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, Pietroni MC, Williams R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg. 1973;60:646-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5490] [Cited by in RCA: 5821] [Article Influence: 109.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 16. | Brooks D, Solway S, Gibbons WJ. ATS statement on six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:1287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 234] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Campillo B, Fouet P, Bonnet JC, Atlan G. Submaximal oxygen consumption in liver cirrhosis. Evidence of severe functional aerobic impairment. J Hepatol. 1990;10:163-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Chiang LL, Yu CT, Liu CY, Lo YL, Kuo HP, Lin HC. Six-month nocturnal nasal positive pressure ventilation improves respiratory muscle capacity and exercise endurance in patients with chronic hypercapnic respiratory failure. J Formos Med Assoc. 2006;105:459-467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kelbaek H, Rabøl A, Brynjolf I, Eriksen J, Bonnevie O, Godtfredsen J, Munck O, Lund JO. Haemodynamic response to exercise in patients with alcoholic liver cirrhosis. Clin Physiol. 1987;7:35-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Epstein SK, Ciubotaru RL, Zilberberg MD, Kaplan LM, Jacoby C, Freeman R, Kaplan MM. Analysis of impaired exercise capacity in patients with cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:1701-1707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wiesinger GF, Quittan M, Zimmermann K, Nuhr M, Wichlas M, Bodingbauer M, Asari R, Berlakovich G, Crevenna R, Fialka-Moser V. Physical performance and health-related quality of life in men on a liver transplantation waiting list. J Rehabil Med. 2001;33:260-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wong F, Girgrah N, Graba J, Allidina Y, Liu P, Blendis L. The cardiac response to exercise in cirrhosis. Gut. 2001;49:268-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Gibbons WJ, Fruchter N, Sloan S, Levy RD. Reference values for a multiple repetition 6-minute walk test in healthy adults older than 20 years. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2001;21:87-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 337] [Cited by in RCA: 364] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Enright PL, Sherrill DL. Reference equations for the six-minute walk in healthy adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:1384-1387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1246] [Cited by in RCA: 1418] [Article Influence: 50.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 25. | Troosters T, Gosselink R, Decramer M. Six minute walking distance in healthy elderly subjects. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:270-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 613] [Cited by in RCA: 640] [Article Influence: 23.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 26. | Mancini DM, Katz SD, Lang CC, LaManca J, Hudaihed A, Androne AS. Effect of erythropoietin on exercise capacity in patients with moderate to severe chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2003;107:294-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 365] [Cited by in RCA: 402] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Horwich TB, Fonarow GC, Hamilton MA, MacLellan WR, Borenstein J. Anemia is associated with worse symptoms, greater impairment in functional capacity and a significant increase in mortality in patients with advanced heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1780-1786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 481] [Cited by in RCA: 491] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Younossi ZM, Boparai N, Price LL, Kiwi ML, McCormick M, Guyatt G. Health-related quality of life in chronic liver disease: the impact of type and severity of disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2199-2205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Remy AJ, Daurès JP, Tanguy G, Khemissa F, Chevrier M, Lezotre PL, Blanc P, Larrey D. [Measurement of the quality of life in chronic hepatitis C: validation of a general index and specific index. First French results]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1999;23:1296-1309. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Bowen JB, Votto JJ, Thrall RS, Haggerty MC, Stockdale-Woolley R, Bandyopadhyay T, ZuWallack RL. Functional status and survival following pulmonary rehabilitation. Chest. 2000;118:697-703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Paciocco G, Martinez FJ, Bossone E, Pielsticker E, Gillespie B, Rubenfire M. Oxygen desaturation on the six-minute walk test and mortality in untreated primary pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2001;17:647-652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 175] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Mercer TH, Naish PF, Gleeson NP, Wilcock JE, Crawford C. Development of a walking test for the assessment of functional capacity in non-anaemic maintenance dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13:2023-2026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

S- Editor Zhu LH L- Editor Roberts SE E- Editor Liu Y