Published online Feb 7, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i5.818

Revised: June 29, 2005

Accepted: July 28, 2005

Published online: February 7, 2006

The congenital dyserythropoietic anemias comprise a group of rare hereditary disorders of erythropoiesis, characterized by ineffective erythropoiesis as the predominant mechanism of anemia and by characteristic morphological aberrations of the majority of erythroblasts in the bone marrow. Congenital dyserythropoietic anemia type II is the most frequent type. All types of congenital dyserythropoietic anemias distinctly share a high incidence of iron loading. Iron accumulation occurs even in untransfused patients and can result in heart failure and liver cirrhosis. We have reported about a patient who presented with liver cirrhosis and intractable ascites caused by congenital dyserythropoietic anemia type II. Her clinical course was further complicated by the development of autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Splenectomy was eventually performed which achieved complete resolution of ascites, increase of hemoglobin concentration and abrogation of transfusion requirements.

- Citation: Vassiliadis T, Garipidou V, Perifanis V, Tziomalos K, Giouleme O, Patsiaoura K, Avramidis M, Nikolaidis N, Vakalopoulou S, Tsitouridis I, Antoniadis A, Semertzidis P, Kioumi A, Premetis E, Eugenidis N. A case of successful management with splenectomy of intractable ascites due to congenital dyserythropoietic anemia type II-induced cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(5): 818-821

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i5/818.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i5.818

All types of congenital dyserythropoietic anemias (CDAs) distinctly share a high incidence of iron loading[1]. As in other forms of anemia with ineffective erythropoiesis, this is due to the upregulation of iron resorption[2]. Iron accumulation occurs even in untransfused patients and can result in diabetes mellitus, hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and more importantly, heart failure and liver cirrhosis[3-5].

We have reported about a patient who presented with liver cirrhosis and intractable ascites caused by CDA II. Her clinical course was further complicated by the development of autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Splenectomy was eventually performed, which achieved complete resolution of ascites, increase of hemoglobin concentration and abrogation of transfusion requirements.

A 58-year-old female presented to our department because of progressive abdominal distention. She had a history of CDA II that was diagnosed 15 years ago, and received blood transfusion only at the time of diagnosis and never again.

Physical examination revealed mild jaundice and abdominal distention. The edge of the liver extended 3 cm below the right costal margin and marked splenomegaly was also found. Percussion of the abdomen revealed the presence of flank dullness and “shifting”.

The results of laboratory tests were: WBC 7 700/μL, Hb 9.8 g/dL, MCV 91.7 μm3, MCH 32.1 pg, PLT 223 000/μL, PT 13.9, INR 1.07, PTT 28.0, glucose 120 mg/dL, urea 53 mg/dL, creatinine 0.9 mg/dL, AST 81 U/L, ALT 117 U/L, LDH 176 U/L, protein 7.0 g/dL, albumin 4.3 g/dL, total bilirubin 1.76 mg/dL, unconjugated bilirubin 1.44 mg/dL, ferritin 2 200 ng/mL. Folic acid was 7.4 ng/mL (normal range, >5.38 ng/mL) and vitamin B12 was 352 pg/mL (normal range, 211-911 pg/mL), thus ruling out megaloblastic anemia. Hemoglobin electrophoresis showed normal findings.

Analysis of the ascitic fluid obtained after abdominal paracentesis yielded the following results: absolute polymorphonuclear leukocyte count 100/mm3, albumin 1.0 g/dL (serum-ascites albumin gradient 3.3 g/dL), glucose 128 mg/dL, LDH 43 U/L.

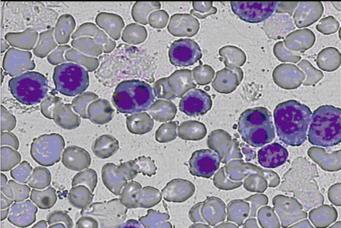

Peripheral blood smear showed anisopoikilocytosis, basophilic stippling and binucleated normoblasts (Figure 1). The Ham’s test was negative, possibly because of a small amount of normal sera used. Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in the presence of sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS-PAGE) of erythrocyte membrane proteins showed that band 3 was narrower and had an accelerated migration rate. Bone marrow examination revealed marked erythroid hyperplasia, while approximately 30% of the mature erythroblasts were binucleate.

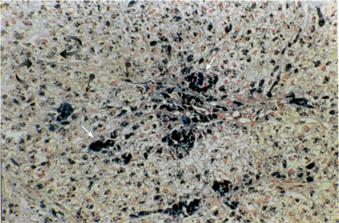

A liver biopsy documented cirrhosis with marked siderosis of hepatocytes as well as Kupffer cells and portal macrophages (Figure 2). Genetic testing for mutations of the HFE gene revealed heterozygosity for the H63D mutation, whereas the patient was negative for the C282Y mutation. Other causes of cirrhosis were thoroughly excluded, based on the medical history of the patient, negative virology for hepatitis B and C, normal immunologic tests (including testing for the presence of antinuclear antibodies, anti-smooth muscle cell antibodies and anti-mitochondrial antibodies) and liver biopsy findings.

Upper endoscopy revealed the presence of esophageal varices. An abdominal ultrasonographic study showed cholelithiasis. A cardiac ultrasonographic examination showed concentric hypertrophy and impaired diastolic function of the left ventricle, left atrium dilatation, mitral valve regurgitation and right ventricle dilatation with tricuspid valve regurgitation and pulmonary hypertension (right ventricular systolic pressure: 5 332 Pa). Magnetic resonance imaging was performed in order to determine heart and liver iron concentration using a unit (Magnetom Impact; Siemens, Germany) operating at a field strength of 1.0 Tesla. We used an electrocardiogram-triggered gradient-recalled-echo sequence for the evaluation of both myocardial and liver iron. Iron content measurement was based on a modification of the method of Bonkovsky, calculating the natural logarithm of the ratio of the mean signal intensity of the liver or heart respectively by that of the standard deviation of the mean of the signal intensity of the overlying air [ln signal intensity ratio, ln (SIR); normal values for both heart and liver, > 3.2][6]. The ln (SIR) values obtained for the heart and liver were 2.66 and 1.26 respectively.

Since the patient persistently refused to undergo iron chelation therapy with desferrioxamine, deferiprone (75 mg/kg per day in three divided doses) was initiated, spironolactone (200 mg once daily) and furosemide (80 mg once daily) were also prescribed but dose escalation was not possible because of deterioration in renal function. Since the patient also did not decrease her salt intake, large volume of paracentesis (approximately 8-10 L of ascitic fluid) had to be performed approximately every 10 d due to the development of refractory ascites.

Soon after her presentation, the patient began to require frequent blood transfusions. Direct antiglobulin test was positive due to the presence of IgG autoantibodies. Extensive investigation, including repeated immunologic tests to rule out autoimmune diseases and imaging studies to rule out occult malignancy, excluded secondary causes of autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA). The patient was treated with prednisone and subsequently with intravenous immunoglobulin, both failed to produce a significant response. Therefore, we performed splenectomy in order to control both CDA and AIHA as well as proximal splenorenal shunt in order to relieve portal hypertension and ascites. Surgery and recovery were uneventful, but a Doppler examination performed immediately after the operation showed complete shunt occlusion.

During the 10-mo post-operative follow-up period, the patient was transfusion-independent and ascites did not relapse although diuretics were discontinued. Hemoglobin concentration was persistently above 12.0 g/dL and unconjugated bilirubin was normalized. Nevertheless, the concentration of ferritin remained elevated at 1 800 ng/mL. A new cardiac ultrasonographic examination disclosed regression of the right ventricle dilatation and no signs of pulmonary hypertension (right ventricular systolic pressure: 1 999.5 Pa). Follow-up magnetic resonance imaging of the heart and liver showed heart siderosis within normal limits but no change in liver siderosis with her ln (SIR) values being 4.04 and 1.38, respectively.

The evolution of CDA II is doomed by iron overloading, which is also seen in patients with no need for transfusion and is mainly due to increased iron resorption. Lethal organ damage of the liver and myocardium is observed in untreated patients[7]. The rate of iron accumulation seems not to be affected by HFE gene polymorphism[8,9]. Our patient was heterozygous for the H63D mutation, which may contribute to increased hepatic iron levels but does not result in iron overload in the absence of the main mutation responsible for hereditary hemosiderosis (C282Y)[10-12].

Hemosiderosis in CDA type II is treated with desferrioxamine which is usually introduced as soon as ferritin reaches the concentration of 1 000 ng/mL[13,14]. Normal ferritin concentrations were reached in all the patients with satisfactory compliance[4] a full-stop Nevertheless, desferrioxamine must be given 5 to 7 d per week by a prolonged subcutaneous infusion[15]. On the other hand, deferiprone is an alternative chelator that is orally active and more effective than desferrioxamine in the removal of myocardial iron[16]. Indeed, heart siderosis returned to normal levels in our patient, even though the reduction in ferritin levels and liver iron overload was not so pronounced.

In CDA II, splenectomy leads to a moderate and sustained increase in hemoglobin concentration and decrease of hemolysis[4,8]. Though splenectomy has these benefits, recommendation for the operation is not uniform among the hematologists[8]. Furthermore, splenectomy does not prevent further iron loading, even in those patients with their hemoglobin concentrations becoming nearly normal as observed in our patient[4].

The concurrence of CDA II and AIHA has been described only once, thus suggesting chance occurrence[17]. In AIHA, splenectomy has the distinct advantage over other therapeutic options in that it has the potential for complete and long-term remission. Available data suggest that it triggers remission in more than 50% of patients[18]. Excellent responses or improvements are maintained during a mean follow-up period of 33 or 73 mo, respectively[19]. Accordingly, splenectomy should be considered in patients who do not respond adequately to corticosteroids[20].

In patients with refractory ascites, both transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) and surgical portal systemic shunt have been used[21]. TIPS is a widely accepted percutaneous interventional procedure for treating complications of portal hypertension. An experienced skillful team, however, is necessary to ensure the technical success of TIPS and to avoid its potential procedural complications[22]. Shunt dysfunction is also a major problem, since over 50% of TIPS develop stenosis within 1 year and therefore, close shunt surveillance and frequent re-treatment are required with ensuing high costs[23-25]. Furthermore, hepatic encephalopathy is another important complication of cirrhotic patients with refractory ascites treated with TIPS, more than 40% of these patients develop encephalopathy[26,27]. Nevertheless, calibrated prosthesis can partly prevent TIPS complications[28].

The role of surgery in the treatment of portal hypertension remains a complex and highly controversial issue. Several factors must be considered when surgical options are to be entertained, including origin and extent of liver disease, response to prior medical treatment, and possibility of future liver transplantation[29]. Splenectomy was mandatory in our patient in order to control CDA and particularly AIHA. However, splenectomy alone is inappropriate for the treatment of portal hypertension and does not relieve ascites[30,31]. In contrast, portosystemic shunting is efficient in clearing ascites, but is associated with a high rate of encephalopathy and liver failure[29,32,33]. The indications for portosystemic shunting are therefore limited for the treatment of intractable ascites and portosystemic shunting should be performed only in patients with good liver function or when all other treatments fail[29,32]. Since our patient had preserved hepatic synthetic capacity, we chose to combine splenectomy with portosystemic shunting in order to relieve ascites and thus performed proximal splenorenal shunt. Compared to selective shunts, the central or proximal splenorenal shunt does not differ in operative mortality rates, 5-year survival rates, development of individual episodes of post-operative encephalopathy, or chronic post-operative encephalopathy[34]. Unfortunately, shunt occlusion may occur immediately after the operation. It is thus difficult to explain the complete remission of ascites and we can only postulate that a reduction in the blood flow into the portal system from the greatly enlarged spleen may result in a decrease in portal pressure. This reduction in portal pressure may also contribute to the amelioration of pulmonary hypertension as observed in our patient.

In conclusion, even in transfusion-independent patients with CDA II, iron overload can result in dramatic manifestations, posing major therapeutic difficulties. Therefore, ferritin levels should be controlled in all the patients with CDA II, because iron overload may approach risk levels at any age[1]. Iron depletion has to be started at the latest when ferritin approaches a level of 1 000 ng/mL to avoid the devastating complications of excessive iron accumulation[4].

| 1. | Heimpel H. Congenital dyserythropoietic anemias: epidemiology, clinical significance, and progress in understanding their pathogenesis. Ann Hematol. 2004;83:613-621. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cazzola M, Barosi G, Bergamaschi G, Dezza L, Palestra P, Polino G, Ramella S, Spriano P, Ascari E. Iron loading in congenital dyserythropoietic anaemias and congenital sideroblastic anaemias. Br J Haematol. 1983;54:649-654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Iolascon A, D'Agostaro G, Perrotta S, Izzo P, Tavano R, Miraglia del Giudice B. Congenital dyserythropoietic anemia type II: molecular basis and clinical aspects. Haematologica. 1996;81:543-559. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Heimpel H, Anselstetter V, Chrobak L, Denecke J, Einsiedler B, Gallmeier K, Griesshammer A, Marquardt T, Janka-Schaub G, Kron M. Congenital dyserythropoietic anemia type II: epidemiology, clinical appearance, and prognosis based on long-term observation. Blood. 2003;102:4576-4581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Greiner TC, Burns CP, Dick FR, Henry KM, Mahmood I. Congenital dyserythropoietic anemia type II diagnosed in a 69-year-old patient with iron overload. Am J Clin Pathol. 1992;98:522-525. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Bonkovsky HL, Rubin RB, Cable EE, Davidoff A, Rijcken TH, Stark DD. Hepatic iron concentration: noninvasive estimation by means of MR imaging techniques. Radiology. 1999;212:227-234. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Kremer Hovinga JA, Solenthaler M, Dufour JF. Congenital dyserythropoietic anaemia type II (HEMPAS) and haemochromatosis: a report of two cases. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15:1141-1147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wickramasinghe SN. Congenital dyserythropoietic anaemias: clinical features, haematological morphology and new biochemical data. Blood Rev. 1998;12:178-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Van Steenbergen W, Matthijs G, Roskams T, Fevery J. Noniatrogenic haemochromatosis in congenital dyserythropoietic anaemia type II is not related to C282Y and H63D mutations in the HFE gene: report on two brothers. Acta Clin Belg. 2002;57:79-84. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Bacon BR, Powell LW, Adams PC, Kresina TF, Hoofnagle JH. Molecular medicine and hemochromatosis: at the crossroads. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:193-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bacon BR, Olynyk JK, Brunt EM, Britton RS, Wolff RK. HFE genotype in patients with hemochromatosis and other liver diseases. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:953-962. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Moirand R, Jouanolle AM, Brissot P, Le Gall JY, David V, Deugnier Y. Phenotypic expression of HFE mutations: a French study of 1110 unrelated iron-overloaded patients and relatives. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:372-377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Fargion S, Valenti L, Fracanzani AL, Sampietro M, Cappellini MD, Scaccabarozzi A, Soligo D, Mariani C, Fiorelli G. Hereditary hemochromatosis in a patient with congenital dyserythropoietic anemia. Blood. 2000;96:3653-3655. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Wonke B. Clinical management of beta-thalassemia major. Semin Hematol. 2001;38:350-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Modell B, Khan M, Darlison M. Survival in beta-thalassaemia major in the UK: data from the UK Thalassaemia Register. Lancet. 2000;355:2051-2052. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 417] [Cited by in RCA: 422] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 16. | Anderson LJ, Wonke B, Prescott E, Holden S, Walker JM, Pennell DJ. Comparison of effects of oral deferiprone and subcutaneous desferrioxamine on myocardial iron concentrations and ventricular function in beta-thalassaemia. Lancet. 2002;360:516-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 305] [Cited by in RCA: 308] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Schmidt ML, Joshi S, DeChristopher PJ, Mihalov M, Sosler SD. Successful management of concurrent congenital dyserythropoietic anaemia and autoimmune haemolytic anaemia with splenectomy. Br J Haematol. 1998;102:1182-1186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Akpek G, McAneny D, Weintraub L. Comparative response to splenectomy in Coombs-positive autoimmune hemolytic anemia with or without associated disease. Am J Hematol. 1999;61:98-102. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Coon WW. Splenectomy in the treatment of hemolytic anemia. Arch Surg. 1985;120:625-628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Petz LD. Treatment of autoimmune hemolytic anemias. Curr Opin Hematol. 2001;8:411-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Arroyo V, Colmenero J. Ascites and hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis: pathophysiological basis of therapy and current management. J Hepatol. 2003;38 Suppl 1:S69-S89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Rösch J, Keller FS. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: present status, comparison with endoscopic therapy and shunt surgery, and future prospectives. World J Surg. 2001;25:337-45; discussion 345-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Bosch J, Abraldes JG, Groszmann R. Current management of portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2003;38 Suppl 1:S54-S68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 170] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Casado M, Bosch J, García-Pagán JC, Bru C, Bañares R, Bandi JC, Escorsell A, Rodríguez-Láiz JM, Gilabert R, Feu F. Clinical events after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: correlation with hemodynamic findings. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:1296-1303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 336] [Cited by in RCA: 319] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Lind CD, Malisch TW, Chong WK, Richards WO, Pinson CW, Meranze SG, Mazer M. Incidence of shunt occlusion or stenosis following transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt placement. Gastroenterology. 1994;106:1277-1283. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Sanyal AJ, Freedman AM, Shiffman ML, Purdum PP, Luketic VA, Cheatham AK. Portosystemic encephalopathy after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: results of a prospective controlled study. Hepatology. 1994;20:46-55. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Rössle M, Ochs A, Gülberg V, Siegerstetter V, Holl J, Deibert P, Olschewski M, Reiser M, Gerbes AL. A comparison of paracentesis and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting in patients with ascites. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1701-1707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 421] [Cited by in RCA: 386] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 28. | Boyer TD, Haskal ZJ. The role of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in the management of portal hypertension. Hepatology. 2005;41:386-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 315] [Cited by in RCA: 303] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Iannitti DA, Henderson JM. The role of surgery in the treatment of portal hypertension. Clin Liver Dis. 1997;1:99-114, xi. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Orloff MJ, Orloff MS, Girard B, Orloff SL. Bleeding esophagogastric varices from extrahepatic portal hypertension: 40 years' experience with portal-systemic shunt. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;194:717-28; discussion 728-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | el-Khishen MA, Henderson JM, Millikan WJ, Kutner MH, Warren WD. Splenectomy is contraindicated for thrombocytopenia secondary to portal hypertension. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1985;160:233-238. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Elcheroth J, Vons C, Franco D. Role of surgical therapy in management of intractable ascites. World J Surg. 1994;18:240-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Castells A, Saló J, Planas R, Quer JC, Ginès A, Boix J, Ginès P, Gassull MA, Terés J, Arroyo V. Impact of shunt surgery for variceal bleeding in the natural history of ascites in cirrhosis: a retrospective study. Hepatology. 1994;20:584-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

S- Editor Wang XL and Guo SY L- Editor Elsevier HK E- Editor Cao L