Published online Dec 7, 2006. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i45.7313

Revised: August 28, 2006

Accepted: October 20, 2006

Published online: December 7, 2006

AIM: To assess the extent and reasons of non-compliance in surveillance for patients undergoing polypectomy of large (≥ 1 cm) colorectal adenomas.

METHODS: Between 1995 and 2002, colorectal adenomas ≥ 1 cm were diagnosed in 210 patients and subsequently documented at the Erlangen Registry of Colorectal Polyps. One hundred and fifty-eight patients (75.2%) could be contacted by telephone and agreed to be interviewed. Additionally, records were obtained from the treating physicians.

RESULTS: Fifty-four out of 158 patients (34.2%) neglected any surveillance. Reasons for non-compliance included lack of knowledge concerning surveillance intervals (45.8%), no symptoms (29.2%), fear of examination (18.8%) or old age/severe illness (6.3%). In a multivariate analysis, the factors including female gender (P = 0.036) and age > 62 years (P = 0.016) proved to be significantly associated with non-compliance in surveillance.

CONCLUSION: Efforts to increase compliance in surveillance are of utmost importance. This applies particularly to women’s compliance. Effective strategies for avoiding metachronous colorectal adenoma and cancer should focus on both the improvement in awareness and knowledge of patients and information about physicians for surveillance.

- Citation: Brueckl WM, Fritsche B, Seifert B, Boxberger F, Albrecht H, Croner RS, Wein A, Hahn EG. Non-compliance in surveillance for patients with previous resection of large (≥ 1 cm) colorectal adenomas. World J Gastroenterol 2006; 12(45): 7313-7318

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v12/i45/7313.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i45.7313

Regular surveillance is strongly recommended for patients who have undergone an intestinal polypectomy due to the high adenoma recurrence rate and elevated risk of subsequent colorectal cancer (CRC)[1-4]. In particular, according to the guidelines of the Germany Society of Digestion and Metabolism [Deutsche Gesellschaft für Verdauung und Stoffwechsel (DGVS)], a surveillance colonoscopy should be performed in Germany not longer than 3 years after the initial polypectomy, regardless whether a single or multiple adenoma is resected[4]. When no metachronous adenoma is found at the 3-year surveillance colonoscopy, the next surveillance colonoscopy should be performed no later than 5 years. Clinically important colorectal adenomas include large (≥ 1 cm) lesions, those with a high degree of dysplasia, and those with villous histology. In particular, adenoma diameter is considered an important marker of malignant potential due to the fact that a larger adenoma at baseline is associated with a higher risk of CRC[5,6]. In persons who have been found to have a large colorectal adenoma, the colon cancer incidence rate is approximately 4 times higher than the normally expected incidence rate[7-10]. In a study by Gandhi et al[11], the 5-year recurrence rate after polypectomy of a colorectal adenoma was 40.93% (1651/4046) while the malignancy rate was 2.17% (88/4046). Although the length and schedules of surveillance programs are not clarified, a follow-up interval of no longer than 3 years in high-risk patients seems justified[4,12].

However, only 11%-51% of all participants with a resected polyp (≥ 1 cm in diameter) have ever returned for a follow-up colonoscopy[2,3,13,14]. Little is known about the reasons of non-compliance in those high-risk patients. However, awareness of the underlying reasons is the cornerstone for changing the prevailing attitude towards colonoscopy surveillance. Therefore, the purpose of this retrospective study was to evaluate the surveillance behavior in patients undergone resection of a clinically relevant (≥ 1 cm) colorectal adenoma.

The Erlangen Registry of Colorectal Polyps (ERCRP) was established in 1978. Since then all clinico-pathological features concerning resected colorectal carcinomas have been prospectively recorded in this database. In addition, all colorectal polyps removed by endoscopy in the Department of Medicine or in the Department of Surgery of Erlangen University Hospital were prospectively documented and histologically categorized by the Department of Pathology in accordance with the WHO classification[15]. The size of all removed adenomas was accurately measured in the Department of Pathology. Patients whose adenomas were proved to contain invasive carcinomas at the initial examination and patients with inflammatory bowel disease were excluded from this survey. According to the guidelines of the DGVS, a surveillance colonoscopy should be performed after polypectomy at a time interval no longer than three years[4]. These recommendations were part of the discharge letter after initial polypectomy. However, automatic reminders for surveillance colonoscopies were usually not sent to the patients. The present study comprised the period from 1995 to 2002, because prior to these period follow-up recommendations have not been specified and a follow-up no longer than 3 years seemed to be adequate.

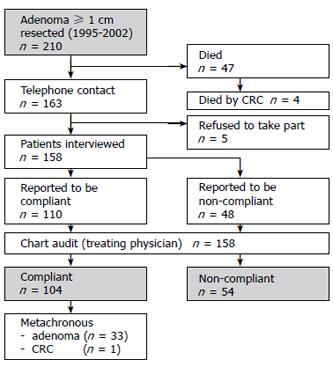

From 1995 to 2002, colorectal adenomas (≥ 1 cm in diameter) were diagnosed in 210 patients by complete colonoscopy. These adenomas were subsequently resected by endoscopic polypectomy or by surgery. Whether the death of 47 patients was due to CRC was evaluated according to the data obtained from the corresponding treating physician.

A total of 163 patients were still alive at the time of our study and could be contacted by telephone. Verbal consent was obtained about their willingness to take part in this survey and to obtain additional information from the treating physician before starting the interview. After the exclusion of 5 patients who refused to take part in this survey, 158 patients were interviewed by a trained research assistant.

Our standardized interview consisted of 10 questions. In the case of non-attendance to the follow-up colono-scopy, some items were skipped and the reasons of non-compliance were asked as shown in Appendix 1.

Additionally, the treating physician of the respective patient was addressed by an official letter from our depart-ment, in which he/she was asked to answer a standardized interview of 4 questions shown in Appendix 2.

In the case of not answering our survey for six weeks after having posted the letter, the corresponding physician was called by telephone and the interview based on the interview items, was orally performed.

Information on age, gender, localization of the initial adenoma and indication for initial polypectomy were obtained from the Erlangen Registry of Colorectal Polyps (ERCRP). An overview about the study setup is shown in Figure 1.

The significance of differences between the specific proportions was tested by the Fisher’s exact test and differences between average values by the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test. Two-sided P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The relative importance of risk factors was assessed by the Cox’s stepwise proportional hazard model. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 13 ( SPSS Inc, Chicago, USA).

A total of 210 patients with a colorectal adenoma (≥ 1 cm in diameter) were diagnosed at Erlangen University Hospital and tested for surveillance. No interview could be carried out with 52 patients, either because they refused to take part in the survey (n = 5) or because they died (n = 47). According to the corresponding records or to the information given by the treating physician and the civil registry office records, death occurred in 4 (8.5%) of 47 patients at a median period of 9. 2 years after initial colonoscopy due to CRC.

One hundred and fifty-eight patients could be interviewed. The clinico-pathological characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. One hundred and four (65.8%) out of the 158 patients underwent regular surveillance colonoscopies. In 33 out of the 104 patients (31.7%) at least one metachronous adenoma was discovered in at least one of the surveillance colonoscopies. The median size of the metachronous adenoma was 1.3 cm (range 0.3 cm to 2.2 cm). A colonic cancer [transverse colon, pT2pN0M0 (UICC I)] was diagnosed in one out of 104 surveillance participants and could resected in a curative (R0) manner. An incongruence between the statements of the patients and treating physician concerning the existence of metachronous adenomas was found in 7 (6.7%) out of the 104 patients. Of the 7 patients, 3 wrongly assumed that they had a metachronous colorectal adenoma, and 4 assumed that they had no metachronous adenoma in contrast to the records. The size (P = 0.318), localization (P = 0.213) and histology (P = 0.268) of adenoma as well as the grade of dysplasia (P = 0.135) were not significantly associated with compliance. Furthermore, education (P = 0.979), daily intake of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) (P = 0.140) and a family history of CRC (P = 0.441) were not significantly related to compliance.

| Compliance Non-compliance(n = 110) (n = 48)n (%) n (%) | P1 | ||

| Sex | |||

| Male | 69 (73.4) | 25 (26.6) | |

| Female | 35 (54.7) | 29 (45.3) | 0.015 |

| Age | |||

| ≤ 62 yr | 64 (75.3) | 21 (24.7) | |

| > 62 yr | 40 (54.8) | 33 (45.2) | 0.007 |

| Education | |||

| < high school degree | 83 (65.9) | 43 (34.1) | |

| ≥ high school degree | 21 (65.6) | 11 (34.4) | 0.979 |

| Size of adenoma | |||

| 10 -15 mm | 51 (62.2) | 31 (37.8) | |

| > 15 mm | 53 (69.7) | 23 (30.3) | 0.318 |

| Localisation | |||

| Rectum | 24 | 13 | |

| Left Colon | 50 | 31 | |

| Right Colon | 28 | 10 | 0.213 |

| Histology | |||

| Tubulous | 35 (61.4) | 22 (38.6) | |

| Tubulovillous | 61 (66.3) | 31 (33.7) | |

| Villous | 8 (88.9) | 1 (11.1) | 0.268 |

| Dysplasia | |||

| Mild | 19 (63.3) | 11 | |

| Moderate | 72 (70.6) | 30 (29.4) | |

| Severe | 13 (50.0) | 13 (50.0) | 0.135 |

| Family history of CRC | |||

| Yes | 14 (73.7) | 5 (26.3) | |

| No | 90 (64.7) | 49 (35.3) | 0.441 |

| NSAID intake | |||

| Yes | 26 (76.5) | 8 (23.5) | |

| No | 78 (62.9) | 46 (37.1) | 0.140 |

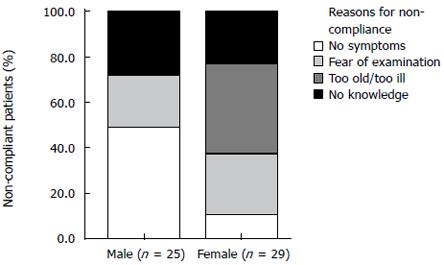

Fifty-four (34.2%) out of 158 patients did not participate in a current surveillance program. Forty-eight (88.9%) out of 54 patients communicated this fact during the telephone interview, and discrepancies between the statements of the patients and the treating physician were found in 6 patients. The main reasons why the 48 patients did not report compliance included no knowledge about the surveillance intervals (n = 22, 45.8%), no symptoms (n = 14, 29.2%), fear of examination (n = 9, 18.8%) or old age/severe illness (n = 3, 6.3%). Difference in gender was also the reason for non-compliance. Male participants reported mainly that they had no symptoms while female patients explained that they had no knowledge about the surveillance intervals. However, there was a trend towards significance in this gender specific difference (P = 0.071) (Figure 2).

Stratifying various clinico-pathological features between compliance and non-compliance showed that the factors including age > 62 years (P = 0.011) and female gender (P = 0.021) were significantly associated with non-compliance. A multivariate analysis revealed that both were proved to be independent factors for non-compliance (Table 2).

| hazard ratio | 95% CI | P1 | |

| Sex (female vs male) | 2.089 | 1.051-4.157 | 0.036 |

| Age (< 60 yr vs > 60 yr) | 2.326 | 1.171-4.621 | 0.016 |

Our findings show that more attention must be paid to the evaluation of CRC screening and the improvement of screening compliance. More than one third (34.1%) of the patients undergone a polypectomy are still alive, and never have any of the recommended controls. Taking into account that most of the patients who died did not attend any follow-up colonoscopy, up to 48% had non-compliance, which is in concordance with several studies reporting that only 11%-51% of all participants with resected polyp have returned for a follow-up colonoscopy[2,3,13,14]. However, a recently study reported that 91% patients underwent follow-up colonoscopy[6], indicating that accurate recall data of testing are required, especially by the treating physician who is responsible for the follow-up of patients. Indeed, most patients in our study with current surveillance were regularly informed by their treating physician and 93.3% of them had knowledge about the results of the follow-up colonoscopies.

Who are the patients with non-compliance and what is their motivation Unexpectedly, a significantly higher rate of compliance was found in men than in women during surveillance colonoscopies in our study. In particular, female sex was independently associated with non-compliance. This is prima facie surprising and in contrast to data on cancer screening for breast or cervical cancer, according to which 77% of women reported that they have undergone a mammogram and a papanicolaou smear within the past 2 years[16]. However, the participation rates seem to be different in CRC screening where procedures are involved, which may be perceived as disgusting or embarrassing[17]. In particular, only 27% of women undergoing regular breast and cervical cancer screening reported that they have undergone sigmoidoscopy in the preceding 5 years[16]. Furthermore, numerous studies indicate that the participation rates for prophylactic CRC screening are significantly higher in men than in women[18-21]. Although the risk of CRC is similar in men and women, CRC is considered a man’s disease[22].

To our knowledge, no data on gender effects are available so far concerning surveillance colonoscopies after resection of a relevant colorectal adenoma. Therefore, in order to understand and improve the compliance rate, it is most important to know the reasons for refusing follow-up strategies. Furthermore, identifying the reasons for the failure to obtain surveillance is an important public health issue, as early detection of recurrences decreases CRC occurrence and societal cost[23,24].

Not having knowledge about surveillance intervals is the reason for non-compliance most frequently mentioned. In particular, 45% of the non-compliant patients and 50% of the female patients considered that they were not informed of the screening procedures by their physicians. These data show the essential importance of the primary care doctors in colorectal surveillance and are somewhat comparable with data from a study by Mandelson et al[25], who reported that lack of recommendation by their primary care doctor as a reason for not undergoing initial colorectal cancer screening in older women. However, in contrast to our data, probably all patients undergoing polypectomy in their study were told by the endoscopist to return for a surveillance examination. In contrast to USA, automatic reminders are not usually sent out by the specialists in Germany. Therefore, until now, it is the responsibility of patients and their primary care doctors to arrange surveillance colonoscopies.

Interestingly, the non-compliant patients in our study were not more interested in further information on colorectal adenomas and screening recommendations than patients under current surveillance. In particular, only 9 (16.7%) out of 54 patients without any follow-up coloncoscopy were interested in further information. One explanation might be the fact that most of the non-compliant patients were not aware of the importance of follow-up and that they were not sufficiently informed about running an increased risk of recurrent adenomas and CRC in contrast to the whole population. Another possible explanation might be the fact that these persons wished to avoid unfavorable health information[26]. In addition, flexible sigmoidoscopy trial from the United Kingdom showed that interest in information on colorectal screening is significantly associated with attendance at colorectal screening[20], which is in accordance with our data. Having no symptoms is a reason for incompliance. In our study, 45% of the male patients and only 15% of the female patients brought forward this argument. Furthermore, it is a widespread misbelief, especially in male patients, that bowel cancer development is associated with pain and gastrointestinal symptoms at an early stage.

Some limitations should be considered in interpreting our results. Since the study population pertains to a single university hospital, it remains unclear whether our findings are applicable to other populations in other medical settings. Future studies are obviously needed to corroborate our findings and address this potential limitation. Other considerations in generalizing our findings are the limited number of incompliant patients, the amount and reasons of non-compliance. This assumption is supported by the fact that most of the patients had no interest in further information although they were incompliant.

Of the 210 patients in the present study, 5 (2.4%) developed CRC during the follow-up, 4 died of it, and 33 had a diagnosed metachronous adenoma. This is in accordance with data recently published by us and others, showing that patients with clinically relevant adenomas (≥ 1 cm) run an increased risk of recurrence and CRC[3,6,27]. Therefore, careful and frequent total colonoscopies (at intervals not longer than 3 years as long as metachronous adenomas are detected) for patients have to be warranted. Special recommendations have been proposed for patients with a family history of colorectal adenoma or CRC, who ran an increased risk of developing CRC[12].

Family history of CRC was stated by 19 (12.0%) of 158 patients in our study. However, only 14 (73.7%) of the 19 (73.7%) patients with a burden of familial CRC underwent follow-up colonoscopies after a relevant colorectal adenoma was removed. This lack of compliance is consistent with a study by Pho et al[28], who evaluated the communication about familial CRC risk in patients with newly diagnosed colorectal adenomas, and demonstrated evidence of poor communication, as only 41% of the patients were aware of the fact that their first-degree relatives run an increased risk of CRC, and stated the need for novel strategies to promote awareness and facilitate screening.

In conclusion, efforts have to be made to further increase CRC surveillance, especially in patients who have undergone resection of a clinically relevant adenoma. Particularly in women and patients with a family history of CRC or adenoma, effective strategies improving the awareness of recurrence and increased CRC risks are needed. Additionally, a thoughtful design of data management systems that document the available data and inform the treating physicians of screening and surveying patients, is necessary to reduce CRC morbidity and mortality.

The authors thank Dr. Corinna Koebnick, oec. troph., statistics at the German Institute for Nutrition, Potsdam-Rehbruecke, Germany, for statistical supervision.

The standardized interview with the patients contained the following questions and information.

(1) The currently treating physician (name and address);

(2) The question of whether a surveillance colonoscopy was performed not longer than three years after the initial polypectomy (yes/no);

(3) The surveillance intervals and the issue of whether the patient was informed of the pending surveillance colonoscopy;

(4) The main reason for a follow-up colonoscopy (What was the main reason for you to have a follow-up”

□ Routine

□ Having symptoms

(5) The recurrence of metachronous colorectal adenoma (“Has an additional adenoma been discovered at follow-up” (Yes/no).

In the case of non-attendance to the follow-up colonoscopy, items 3-5 were skipped and the patients were asked for

(6) The reasons of non-compliance (“What was the main reason for you not having a follow-up colonoscopy to date”. The possible answers were:

□ Not knowing about follow-up intervals

□ Having no symptoms

□ Having fear about the endoscopic examination

□ Old age / severe illness for surveillance.

All patients were asked for

(7) Known cases of colorectal cancer in the family history (yes/no)

(8) A daily intake of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g. aspirin®) (yes/no)

(9) The attendance to the last grade of high school (which approximately corresponds to the German term “Abitur”) (yes/no)

(10) Their interest in additional information on surveillance after polypectomy (yes/no).

The standardized interview with the treating physicians contained the following questions.

(1) Whether the named patient was under his/her treatment (yes/no)

(2) Whether a family history of previous colorectal cancer incidents was known in the patient concerned (yes/no)

(3) Whether a follow-up colonoscopy was performed

□ Yes

□ No

□ No information

(4) In case of a follow-up colonoscopy, whether a metachronous colorectal adenoma or a carcinoma was ever found (yes/no).

| 1. | Winawer SJ, Zauber AG, Ho MN, O'Brien MJ, Gottlieb LS, Sternberg SS, Waye JD, Schapiro M, Bond JH, Panish JF. Prevention of colorectal cancer by colonoscopic polypectomy. The National Polyp Study Workgroup. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1977-1981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3107] [Cited by in RCA: 3173] [Article Influence: 96.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Neugut AI, Jacobson JS, Ahsan H, Santos J, Garbowski GC, Forde KA, Treat MR, Waye J. Incidence and recurrence rates of colorectal adenomas: a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 1995;108:402-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Fornasarig M, Valentini M, Poletti M, Carbone A, Bidoli E, Sozzi M, Cannizzaro R. Evaluation of the risk for metachronous colorectal neoplasms following intestinal polypectomy: a clinical, endoscopic and pathological study. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:1565-1572. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Schmiegel W, Adler G, Frühmorgen P, Fölsch U, Graeven U, Layer P, Petrasch S, Porschen R, Pox C, Sauerbruch T. [Colorectal carcinoma: prevention and early detection in an asymptomatic population--prevention in patients at risk--endoscopic diagnosis, therapy and after-care of polyps and carcinomas. German Society of Digestive and Metabolic Diseases/Study Group for Gastrointestinal Oncology]. Z Gastroenterol. 2000;38:49-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nusko G, Mansmann U, Partzsch U, Altendorf-Hofmann A, Groitl H, Wittekind C, Ell C, Hahn EG. Invasive carcinoma in colorectal adenomas: multivariate analysis of patient and adenoma characteristics. Endoscopy. 1997;29:626-631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Martínez ME, Sampliner R, Marshall JR, Bhattacharyya AK, Reid ME, Alberts DS. Adenoma characteristics as risk factors for recurrence of advanced adenomas. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1077-1083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Morson BC. The evolution of colorectal carcinoma. Clin Radiol. 1984;35:425-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lotfi AM, Spencer RJ, Ilstrup DM, Melton LJ. Colorectal polyps and the risk of subsequent carcinoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 1986;61:337-343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Atkin WS, Morson BC, Cuzick J. Long-term risk of colorectal cancer after excision of rectosigmoid adenomas. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:658-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 761] [Cited by in RCA: 694] [Article Influence: 20.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Otchy DP, Ransohoff DF, Wolff BG, Weaver A, Ilstrup D, Carlson H, Rademacher D. Metachronous colon cancer in persons who have had a large adenomatous polyp. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:448-454. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Gandhi SK, Reynolds MW, Boyer JG, Goldstein JL. Recurrence and malignancy rates in a benign colorectal neoplasm patient cohort: results of a 5-year analysis in a managed care environment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:2761-2767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Winawer SJ, Fletcher RH, Miller L, Godlee F, Stolar MH, Mulrow CD, Woolf SH, Glick SN, Ganiats TG, Bond JH. Colorectal cancer screening: clinical guidelines and rationale. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:594-642. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1353] [Cited by in RCA: 1251] [Article Influence: 43.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Morson BC, Bussey HJ. Magnitude of risk for cancer in patients with colorectal adenomas. Br J Surg. 1985;72 Suppl:S23-S25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Yang G, Zheng W, Sun QR, Shu XO, Li WD, Yu H, Shen GF, Shen YZ, Potter JD, Zheng S. Pathologic features of initial adenomas as predictors for metachronous adenomas of the rectum. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1661-1665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jass JR, Sobin LH. Histological typing of intestinal tumours. WHO international classification of tumours. Berlin: Springer 1989; . |

| 16. | Hsia J, Kemper E, Kiefe C, Zapka J, Sofaer S, Pettinger M, Bowen D, Limacher M, Lillington L, Mason E. The importance of health insurance as a determinant of cancer screening: evidence from the Women's Health Initiative. Prev Med. 2000;31:261-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lieberman D. How to screen for colon cancer. Annu Rev Med. 1998;49:163-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cockburn J, Thomas RJ, McLaughlin SJ, Reading D. Acceptance of screening for colorectal cancer by flexible sigmoidoscopy. J Med Screen. 1995;2:79-83. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Herbert C, Launoy G, Gignoux M. Factors affecting compliance with colorectal cancer screening in France: differences between intention to participate and actual participation. Eur J Cancer Prev. 1997;6:44-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sutton S, Wardle J, Taylor T, McCaffery K, Williamson S, Edwards R, Cuzick J, Hart A, Northover J, Atkin W. Predictors of attendance in the United Kingdom flexible sigmoidoscopy screening trial. J Med Screen. 2000;7:99-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wardle J, Sutton S, Williamson S, Taylor T, McCaffery K, Cuzick J, Hart A, Atkin W. Psychosocial influences on older adults' interest in participating in bowel cancer screening. Prev Med. 2000;31:323-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Donovan JM, Syngal S. Colorectal cancer in women: an underappreciated but preventable risk. J Womens Health. 1998;7:45-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Lewis JD. Prevention and treatment of colorectal cancer: pay now or pay later. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:647-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Sonnenberg A, Delcò F, Inadomi JM. Cost-effectiveness of colonoscopy in screening for colorectal cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:573-584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 338] [Cited by in RCA: 324] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Mandelson MT, Curry SJ, Anderson LA, Nadel MR, Lee NC, Rutter CM, LaCroix AZ. Colorectal cancer screening participation by older women. Am J Prev Med. 2000;19:149-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Codori AM, Petersen GM, Miglioretti DL, Larkin EK, Bushey MT, Young C, Brensinger JD, Johnson K, Bacon JA, Booker SV. Attitudes toward colon cancer gene testing: factors predicting test uptake. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8:345-351. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Nusko G, Mansmann U, Wiest G, Brueckl W, Kirchner T, Hahn EG. Right-sided shift found in metachronous colorectal adenomas. Endoscopy. 2001;33:574-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Pho K, Geller A, Schroy PC 3rd. Lack of communication about familial colorectal cancer risk associated with colorectal adenomas (United States). Cancer Causes Control. 2000;11:543-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

S- Editor Wang J L- Editor Wang XL E- Editor Liu WF