Published online Jul 28, 2005. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i28.4357

Revised: December 3, 2004

Accepted: December 8, 2004

Published online: July 28, 2005

AIM: A high percentage of early-stage high-grade gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas remainHelicobacter pylori (H pylori)-dependent. However, unlike their low-grade counterparts, high-grade gastric MALT lymphomas may progress rapidly if unresponsive to H pylori eradication. It is mandatory to identify markers that may predict the H pylori-dependent status of these tumors. Proliferation of MALT lymphoma cells depends on cognate help and cell-to-cell contact of H pylori-specific intratumoral T-cells. To examine whether the expression of co-stimulatory marker CD86 (B7.2) and the infiltration of CD56 (+) natural killer (NK) cells can be useful markers to predict H pylori-dependent status of high-grade gastric MALT lymphoma.

METHODS: Lymphoma biopsies from 26 patients who had participated in a prospective study of H pylori-eradication for stage IE high-grade gastric MALT lymphomas were evaluated. Tumors that resolved to Wotherspoon grade II or less after H pylorieradication were classified as H pylori-dependent; others were classified as H pylori-independent. The infiltration of NK cells and the expression of CD86 in pre-treatment paraffin-embedded lymphoma tissues were determined by immunohistochemistry.

RESULTS: There were 16 H pylori-dependent and 10 H pylori-independent cases. CD86 expression was detected in 11 (68.8%) of 16 H pylori-dependent cases but in none of 10 H pylori-independent cases (P = 0.001). H pylori-dependent high-grade gastric MALT lymphomas contained significantly higher numbers of CD56 (+) NK cells than H pylori-independent cases (2.8±1.4% vs 1.10.8%; P = 0.003). CD86 positive MALT lymphomas also showed significantly increased infiltration of CD56 (+) NK cells compared to CD86-negative cases (2.9±1.1% vs 1.4±1.3%; P = 0.005).

CONCLUSION: These results suggest that the expression of co-stimulatory marker CD86 and the increased infiltration of NK cells are associated with H pylori-dependent state of early-stage high-grade gastric MALT lymphomas.

- Citation: Kuo SH, Chen LT, Chen CL, Doong SL, Yeh KH, Wu MS, Mao TL, Hsu HC, Wang HP, Lin JT, Cheng AL. Expression of CD86 and increased infiltration of NK cells are associated with Helicobacter pylori-dependent state of early stage high-grade gastric MALT lymphoma. World J Gastroenterol 2005; 11(28): 4357-4362

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v11/i28/4357.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v11.i28.4357

Extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) of the stomach is the most common extranodal lymphoma of humans. Although not completely acknowledged by all experts, gastric MALT lymphoma is often classified into high-grade and low-grade subtypes by histological criteria[1-3]. Low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma is characterized by its close association with Helicobacter pylori (H pylori) infection; and eradication of H pylori by antibiotics, cures 70% of these tumors[4-6]. However, high-grade gastric MALT lymphomas, in contrast to their low-grade counterparts, are believed to consist of highly-transformed cells, the growth of which is independent of H pylori[7-9].

Recently, several groups of investigators have demonstrated that a substantial portion of early-stage high-grade gastric MALT lymphomas remains H pylori-dependent, and can be cured by H pylori eradication[10-12]. However, high-grade gastric MALT lymphoma, unlike its low-grade counterpart, may progress rapidly if unresponsive to H pylori eradication therapy. Molecular markers such as chromosomal aberration t(11;18), which is highly predictive of H pylori-independent status of low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma, are rarely found in the high-grade counterpart[13]. It is mandatory to identify cellular or molecular markers which can help predict the H pylori-dependent status of newly diagnosed patients.

In the early process of MALT lymphomagenesis, the proliferation response depends at least partly on the stimulation of H pylori-specific intratumoral T-cells[14]. In vitro experiments have demonstrated that the growth and differentiation of MALT lymphoma cells requires CD40-mediated signaling and T helper-2 (Th-2)-type cytokines[15,16]. The dependence on T-cells for the growth of malignant B-cell clones may explain the tendency of early-stage low-grade MALT lymphomas to remain localized and to regress after H pylori eradication. Expression of co-stimulatory molecules, including CD80 (B7.1), CD86 (B7.2), and their ligands, has been demonstrated in gastric MALT lymphoma cells[17]. The presence of the co-stimulatory marker CD86 (B7.2) on lymphoma cells may promote T-cell-mediated neoplastic B cell proliferation. We hypothesized that a loss of co-stimulatory markers might preclude tumor cell/reactive T-cell interaction and thereby contribute to the transition from a H pylori-dependent to a H pylori-independent state in high-grade gastric MALT lymphoma.

CD56 (+) natural killer (NK) cells are important components of the innate immune system, and have the ability to modulate both humoral- and cell-mediated immune responses[18,19]. H pylori can stimulate T-cells and thereby enhance the production of Th-2 cytokines, which can promote the proliferation of CD56 (+) NK cells in gastric MALT lymphomas[20,21]. Although low-grade gastric MALT lymphomas contain significantly higher numbers of CD56 (+) NK cells than high-grade gastric MALT lymphomas[21], the presence of CD56 (+) NK cells in high-grade gastric MALT lymphomas indicate that the promotion of these lymphoma cells triggered by H pylori-specific intratumoral T-cells and Th-2 type cytokines may still be present in vivo. Therefore, these CD56 (+) NK cells may limit the autonomous growth of MALT lymphoma cells, and may contribute to the remission of high-grade MALT lymphomas after the eradication of H pylori.

This study, was conducted to examine the expression of CD86 and the infiltration of CD56 (+) NK cells in 16 H pylori-dependent and 10 H pylori-independent high-grade gastric MALT lymphomas.

Twenty-six patients who had participated in a prospective study of H pylori eradication for stage IE high-grade gastric MALT lymphomas at our institutions from June 1995 to June 2003 were included in this study. The clinicopathologic features of the 22 patients have been previously reported[13]. Although high-grade MALT lymphomas are classified as diffuse large B-cell lymphomas (with areas of marginal zone/MALT-type lymphoma) in the REAL/WHO classification[2], and a consensus on the use of the term high-grade MALT lymphoma has not been achieved, many experts consider it as a useful and reasonable clinicopathologic entity[1,3,10,21]. In this study, the diagnosis of high-grade gastric MALT lymphoma was made using the histologic criteria as described by Chan et al[1] and de Jong et al[3] based on the presence of a diffuse increase of large cells resembling centroblasts or lymphoblasts to between 1% and 10% of the total tumor cells within predominantly low-grade centrocyte-like cell infiltrate, or the predominance of a high-grade lymphoma with only a small residue, low-grade foci and/or the presence of lymphoepithelial lesions. Specimens with occasional clusters of transformed blast cells or sheets of transformed blast cells (upto 20 cells not forming larger sheets) confined within the colonized follicles were found within a low-grade lymphoma, they were considered as an immune response to H pylori stimulation rather than high-grade MALT lymphoma. Patients with primary pure large cell lymphoma, without evidence of a low-grade component of the stomach were excluded from this study. All specimens were immuohi-stochemically stained by CD20, CD79a, CD3, and CD45RO for routine diagnostic purposes and to highlight lymphoepithelial lesions. Moreover, to exclude misinterpretation of reactive, benign germinal centers as transformed foci, CD21 (follicular dendritic cells markers) and BCL-2 (highly suggestive of a neoplastic origin of the blast cells) were included in all cases. The histopathologic characteristics of all tumor specimens were independently reviewed by two expert hematopathologists. Staging was based on Musshoff's modification of the Ann Arbor staging system[22]. Staging procedures included physical examination, routine laboratory tests, inspection of Waldeyer's ring, chest radiography, chest and abdominal CT scan, bone marrow aspiration, and trephine biopsy. Diagnosis of H pylori infection was based on histologic examination, biopsy urease test, or bacterial culture. When at least one test was positive, the cases were considered as H pylori infected. All patients consented to a brief trial of H pylori eradication therapy.

At the beginning of the study period in June 1995, the eradication regimen consisted of amoxicillin 500 mg and metronidazole 250 mg q.i.d., with either bismuth subcitrate 120 mg q.i.d. or omeprazole 20 mg b.i.d., for 4 wk. The regimen was changed to amoxicillin 500 mg q.i.d., clarithromycin 500 mg b.i.d., plus omeprazole 20 mg b.i.d. for 2 wk beginning in March 1996. Patients were scheduled to undergo a first follow-up upper gastrointestinal endoscopic examination 4-6 wk after completion of antimicrobial therapy, and follow-up was then repeated every 6-12 wk until histologic evidence of remission was found. At each follow-up examination, four to six biopsy specimens were taken from the antrum and body of the stomach for aH pylori infection evaluation, and a minimum of six biopsy specimens were taken from each of the tumors and suspicious areas for histologic evaluation. Tumors that resolved to Wotherspoon grade II or less were considered as histological complete remission[4]. Tumors showing both histological and endoscopic complete remission were considered H pylori-dependent. Tumors showing stable or progressive disease on follow-up endoscopic examination and persistent or increasing proportion of large cells on microscopic examination were considered H pylori-independent.

Formalin-fixed paraffin embedded sections cut at a thickness of 4 mm were deparaffinized and rehydrated through xylene and a graded descending series of alcohol. After antigen retrieval by heat treatment in 0.1 mol/L citrate buffer at pH 6.0, endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by 3% H2O2. Briefly, slides were incubated for 30 min in 2.5% normal donkey serum or goat serum. The slides were then incubated overnight at 4 °C either with goat polyclonal anti-CD86 antibody (1:50; AF-141-NA; R&D Systems, Abingdon, UK) or mouse monoclonal anti-CD56 antibody (1:100; NCL-CD56-1B6, Novacastra), and incubated with secondary antibodies (CD86, donkey antigoat immun-oglobulin; CD56, goat antimouse immunoglobulin; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), following the manufacturer's instructions. Finally, antibody binding was detected with the avidin-biotin-peroxidase method. Reaction products were developed using 3, 5-diaminobenzidine (Dako) as a substrate for peroxidase. Sections were counterstained with Mayer's hematoxylin. All the washes were performed in PBS (pH 7.4). Staining was considered as positive for CD86 when the protein was detected in more than 10% of tumor cells. A minimum of 1 000 cells (normal and neoplastic) were counted for each single determination and reported as the percentage of CD56 (+) NK cells in total mononuclear cells.

The primary aims of this study were to investigate the correlation between the H pylori-dependent status of MALT lymphomas, the expression of CD86 and the infiltration of CD56 (+) NK cells. Fisher's exact test and χ2 test were used to analyze the correlation between the H pylori-dependent status of MALT lymphomas with CD86 expression patterns. The results for the CD56 (+) NK cells are expressed as mean±SD of percentages of positive cells in the total cell count for a given marker. Nonparametric Mann-Whitney U test was used to evaluate the difference in the distribution of positive CD56 (+) NK cell count between H pylori-dependent and H pylori-independent high-grade MALT lymphomas and the difference in the distribution of positive CD56 (+) NK cell count between CD86 positive and CD86 negative high-grade MALT lymphomas.

There were 16 patients with H pylori-dependent and 10 patients with H pylori-independent tumors. The clinicopathologic features of these patients are summarized in Table 1. The median duration between H pylori eradication and complete histologic remission was 5.0 mo (range, 1.5-17.7 mo). At a median follow-up of 56 mo (range, 8.0-90 mo), all 16 patients who had achieved complete histologic remission after eradication of H pylori were alive and free of lymphoma. Seven patients whose tumors grossly increased in size or had microscopic findings of an increased large-cell fraction and three patients whose tumor remained grossly stable at the first follow-up endoscopic examination, were immediately referred for systemic chemotherapy.

| Patientnumber | Sex | Age(yr) | Depth of tumorinvasion | Tumor response toH pylori eradication | Current status | ImmunohistochemistryCD86 |

| 1 | F | 48 | Muscularis propria | CR | - | |

| 2 | M | 21 | Muscularis propria | PD | Chemotherapy | - |

| 3 | F | 63 | SD | Chemotherapy | - | |

| 4 | F | 68 | CR | + | ||

| 5 | F | 52 | Submucosa | PD | Chemotherapy | - |

| 6 | F | 42 | Serosa | CR | + | |

| 7 | F | 66 | Serosa | CR | - | |

| 8 | F | 71 | Muscularis propria | CR | + | |

| 9 | F | 54 | CR | + | ||

| 10 | M | 83 | Muscularis propria | PD | Chemotherapy | - |

| 11 | F | 52 | Submucosa | CR | + | |

| 12 | F | 73 | Muscularis propria | CR | + | |

| 13 | M | 46 | Submucosa | CR | - | |

| 14 | F | 38 | CR | - | ||

| 15 | M | 73 | Serosa | PD | Chemotherapy | - |

| 16 | F | 45 | Muscularis propria | PD | Chemotherapy | - |

| 17 | F | 56 | Submucosa | CR | + | |

| 18 | F | 59 | Serosa | PD | C/T+gastrectomy | - |

| 19 | F | 65 | CR | + | ||

| 20 | M | 35 | Submucosa | CR | + | |

| 21 | F | 73 | CR | - | ||

| 22 | M | 45 | Serosa | SD | Chemotherapy | - |

| 23 | F | 53 | Submucosa | SD | Chemotherapy | - |

| 24 | F | 80 | Muscularis propria | PD | Chemotherapy | - |

| 25 | M | 70 | Submucosa | CR | + | |

| 26 | F | 84 | Submucosa | CR | + |

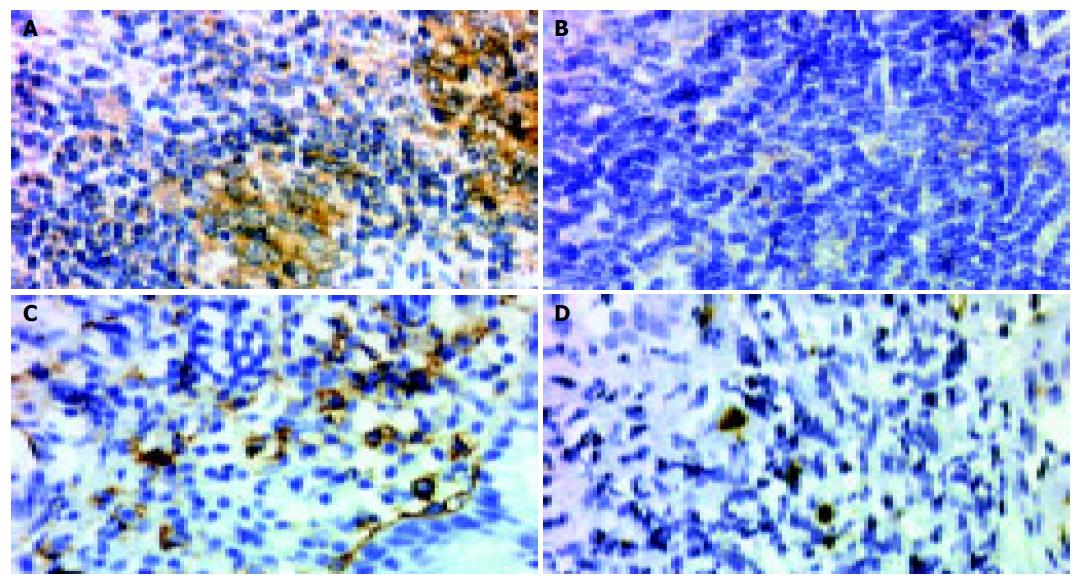

The expression of CD86 was detected in 11 (68.8%) of 16 H pylori-dependent high-grade gastric MALT lymphomas, but in none of 10 H pylori-independent MALT lymphomas (P = 0.001, Figure 1 and Table 1). Therefore, the expression of CD86 had a sensitivity of 68.8% and a specificity of 100% in predicting the H pylori-dependence of high-grade gastric MALT lymphomas.

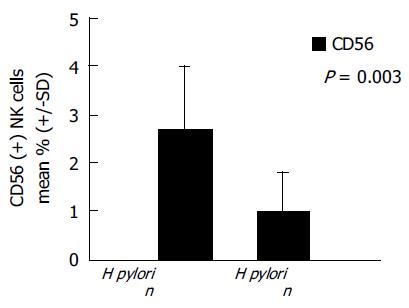

As shown in Figure 2, the infiltration of CD56 (+) NK cells differed between H pylori-dependent and H pylori-independent high-grade gastric MALT lymphomas. H pylori-dependent high-grade gastric MALT lymphomas contained significantly higher numbers of CD56 (+) NK cells than H pylori-independent MALT lymphomas (2.8±1.4% vs 1.1±0.8%; P = 0.003). Meanwhile, CD86 positive MALT lymphomas also showed significantly increased infiltration of CD56 (+) NK cells compared to CD86-negative cases (2.9±1.1% vs 1.4±1.3%; P = 0.005).

In this study, we found that expression of CD86 on tumor cells and increased infiltration of NK cells in tumor tissues wereassociated with the H pylori-dependent status of early-stage high-grade gastric MALT lymphomas. These findings suggest that the interaction of B- and T-cells may play a pivotal role in the determination of antigen-dependence, as well as in the subsequent response to H pylori eradication therapy in a substantial portion of early-stage high-grade gastric MALT lymphomas. Since high-grade gastric MALT lymphomas may progress rapidly if unresponsive to H pylori eradication therapy, this information is invaluable for the physician who must select a first-line treatment.

It has been demonstrated that the growth of MALT lymphomas requires the help of H pylori-reactive tumor-infiltrating T-cells. For effective communication between T-cells and neoplastic B-cells, two subsets of co-stimulatory molecules, CD80 (B7.1) and CD86 (B7.2), of the neoplastic B-cells should interact with CD28 or CTLA-4 of the T-cells[23]. However, the precise role of CD80 and CD86 molecules in the signaling of B-cells remains unclear. In earlier studies, the CD28-CTLA4/B7-signaling pathway was found to be involved in the proliferation and differentiation of B-cells[24,25]. There is also evidence that CD86 may promote proliferation and immunoglobulin synthesis of normal B-cells and malignant B cells[26]. Compared with CD86, CD80 delivered a down-regulator signal for B-cell response[26]. In a recent study of low-grade gastric MALT lymphomas, the expression of CD86 was significantly associated with H pylori-dependence, while CD80 and CD40 and their ligands were not[27]. These results are in line with our observation that the co-stimulatory molecule CD86 is present in high-grade gastric MALT lymphomas, and is also significantly associated with H pylori-dependence. Our findings support the notion that the growth of a substantial portion of early-stage high-grade gastric MALT lymphomas, as well as their low-grade counterparts, remains dependent on functional B-cell/T-cell interaction.

In addition to promoting the proliferation and differentiation of malignant B-cell clones, tumor-infiltrating T-cells in low-grade gastric MALT lymphomas are found to be defective in both perforin-mediated cytotoxicity and Fas-Fas ligand mediated apoptosis[28]. On the other hand, the tumor tissues of high-grade MALT lymphomas appear to contain a much higher number of apoptotic lymphoma cells and CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs)[21]. Study using a murine model demonstrated that Th-1 response and CD8+ CTLs activity were strongly inhibited in the presence of persistent gastric H pylori infection[29]. Moreover, activated CD8+ CTLs may compete with CD56 (+) NK cells and downregulate the function of the latter[17]. Besides regulating the differentiation of CD8+ CTLs, CD56 (+) NK cells may have an equally important role in immune regulation, where they limit the host response to foreign antigens and prevent autoimmunity[18]. Recently, it has been demonstrated that CD56 (+) NK cells can be functionally activated by co-stimulatory molecules through the interaction of their activation receptor and CD86 on target cells, and thereby limit the extent of H pylori-related auto-reactive and neoplastic B lymphoid cells in the stomach[30]. In the current study, we found that H pylori-dependent high-grade MALT lymphomas showed significantly increased infiltration of CD56 (+) NK cells compared to H pylori-independent lymphomas. Interestingly, we also found that CD86 positive MALT lymphomas showed significantly increased infiltration of CD56 (+) NK cells compared to CD86-negative cases. These findings suggest that the loss of H pylori-dependence may be associated with a change in the immunological microenvironment, including a shift towards a Th-1 response that enhances the activity of CD8+ CTLs, and decreases the activity of CD56 (+) NK cells.

In conclusion, the expression of co-stimulatory marker CD86 on lymphoma cells and the increased infiltration of CD56 (+) NK cells in tumor tissues are useful markers in the identification of H pylori-dependent tumors and in the selection of patients for first-line H pylori eradication therapy.

| 1. | Chan JK, Ng CS, Isaacson PG. Relationship between high-grade lymphoma and low-grade B-cell mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma (MALToma) of the stomach. Am J Pathol. 1990;136:1153-1164. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Harris NL, Jaffe ES, Stein H, Banks PM, Chan JK, Cleary ML, Delsol G, De Wolf-Peeters C, Falini B, Gatter KC. A revised European-American classification of lymphoid neoplasms: a proposal from the International Lymphoma Study Group. Blood. 1994;84:1361-1392. [PubMed] |

| 3. | de Jong D, Boot H, van Heerde P, Hart GA, Taal BG. Histological grading in gastric lymphoma: pretreatment criteria and clinical relevance. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1466-1474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wotherspoon AC, Doglioni C, Diss TC, Pan L, Moschini A, de Boni M, Isaacson PG. Regression of primary low-grade B-cell gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Lancet. 1993;342:575-577. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1564] [Cited by in RCA: 1390] [Article Influence: 42.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Du MQ, Isaccson PG. Gastric MALT lymphoma: from aetiology to treatment. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:97-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Boot H, de Jong D. Gastric lymphoma: the revolution of the past decade. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 2002;236:27-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bayerdörffer E, Neubauer A, Rudolph B, Thiede C, Lehn N, Eidt S, Stolte M. Regression of primary gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type after cure of Helicobacter pylori infection. MALT Lymphoma Study Group. Lancet. 1995;345:1591-1594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 652] [Cited by in RCA: 598] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Neubauer A, Thiede C, Morgner A, Alpen B, Ritter M, Neubauer B, Wündisch T, Ehninger G, Stolte M, Bayerdörffer E. Cure of Helicobacter pylori infection and duration of remission of low-grade gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1350-1355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zucca E, Roggero E, Pileri S. B-cell lymphoma of MALT type: a review with special emphasis on diagnostic and management problems of low-grade gastric tumours. Br J Haematol. 1998;100:3-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Morgner A, Miehlke S, Fischbach W, Schmitt W, Müller-Hermelink H, Greiner A, Thiede C, Schetelig J, Neubauer A, Stolte M. Complete remission of primary high-grade B-cell gastric lymphoma after cure of Helicobacter pylori infection. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2041-2048. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Nakamura S, Matsumoto T, Suekane H, Takeshita M, Hizawa K, Kawasaki M, Yao T, Tsuneyoshi M, Iida M, Fujishima M. Predictive value of endoscopic ultrasonography for regression of gastric low grade and high grade MALT lymphomas after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Gut. 2001;48:454-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 12. | Chen LT, Lin JT, Shyu RY, Jan CM, Chen CL, Chiang IP, Liu SM, Su IJ, Cheng AL. Prospective study of Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy in stage I(E) high-grade mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma of the stomach. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:4245-4251. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Kuo SH, Chen LT, Yeh KH, Wu MS, Hsu HC, Yeh PY, Mao TL, Chen CL, Doong SL, Lin JT. Nuclear expression of BCL10 or nuclear factor kappa B predicts Helicobacter pylori-independent status of early-stage, high-grade gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3491-3497. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hussell T, Isaacson PG, Crabtree JE, Spencer J. Helicobacter pylori-specific tumour-infiltrating T cells provide contact dependent help for the growth of malignant B cells in low-grade gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. J Pathol. 1996;178:122-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hauer AC, Finn TM, MacDonald TT, Spencer J, Isaacson PG. Analysis of TH1 and TH2 cytokine production in low grade B cell gastric MALT-type lymphomas stimulated in vitro with Helicobacter pylori. J Clin Pathol. 1997;50:957-959. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Greiner A, Knörr C, Qin Y, Sebald W, Schimpl A, Banchereau J, Müller-Hermelink HK. Low-grade B cell lymphomas of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT-type) require CD40-mediated signaling and Th2-type cytokines for in vitro growth and differentiation. Am J Pathol. 1997;150:1583-1593. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Vyth-Dreese FA, Boot H, Dellemijn TA, Majoor DM, Oomen LC, Laman JD, Van Meurs M, De Weger RA, De Jong D. Localization in situ of costimulatory molecules and cytokines in B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Immunology. 1998;94:580-586. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kos FJ, Engleman EG. Immune regulation: a critical link between NK cells and CTLs. Immunol Today. 1996;17:174-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Horwitz DA, Gray JD, Ohtsuka K, Hirokawa M, Takahashi T. The immunoregulatory effects of NK cells: the role of TGF-beta and implications for autoimmunity. Immunol Today. 1997;18:538-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Biron CA, Nguyen KB, Pien GC, Cousens LP, Salazar-Mather TP. Natural killer cells in antiviral defense: function and regulation by innate cytokines. Annu Rev Immunol. 1999;17:189-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1593] [Cited by in RCA: 1579] [Article Influence: 58.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 21. | Guidoboni M, Doglioni C, Laurino L, Boiocchi M, Dolcetti R. Activation of infiltrating cytotoxic T lymphocytes and lymphoma cell apoptotic rates in gastric MALT lymphomas. Differences between high-grade and low-grade cases. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:823-829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Musshoff K. [Clinical staging classification of non-Hodgkin's lymphomas (author's transl)]. Strahlentherapie. 1977;153:218-221. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Guindi M. Role of activated host T cells in the promotion of MALT lymphoma growth. Semin Cancer Biol. 2000;10:341-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Boussiotis VA, Freeman GJ, Gribben JG, Nadler LM. The role of B7-1/B7-2: CD28/CLTA-4 pathways in the prevention of anergy, induction of productive immunity and down-regulation of the immune response. Immunol Rev. 1996;153:5-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ikemizu S, Gilbert RJ, Fennelly JA, Collins AV, Harlos K, Jones EY, Stuart DI, Davis SJ. Structure and dimerization of a soluble form of B7-1. Immunity. 2000;12:51-60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Suvas S, Singh V, Sahdev S, Vohra H, Agrewala JN. Distinct role of CD80 and CD86 in the regulation of the activation of B cell and B cell lymphoma. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:7766-7775. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 179] [Cited by in RCA: 189] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | de Jong D, Vyth-Dreese F, Dellemijn T, Verra N, Ruskoné-Fourmestraux A, Lavergne-Slove A, Hart G, Boot H. Histological and immunological parameters to predict treatment outcome of Helicobacter pylori eradication in low-grade gastric MALT lymphoma. J Pathol. 2001;193:318-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | D'Elios MM, Amedei A, Manghetti M, Costa F, Baldari CT, Quazi AS, Telford JL, Romagnani S, Del Prete G. Impaired T-cell regulation of B-cell growth in Helicobacter pylori--related gastric low-grade MALT lymphoma. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:1105-1112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Shirai M, Arichi T, Nakazawa T, Berzofsky JA. Persistent infection by Helicobacter pylori down-modulates virus-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T cell response and prolongs viral infection. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:72-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Science Editor Guo SY Language Editor Elsevier HK