Published online May 1, 2004. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i9.1349

Revised: July 20, 2003

Accepted: August 16, 2003

Published online: May 1, 2004

AIM: To evaluate the effectiveness of wireless capsule endoscopy in patients with suspected Crohn’s disease (CD) of the small bowel undetected by conventional modalities, and to determine the diagnostic yield of M2A Given Capsule.

METHODS: From May 2002 to April 2003, we prospectively examined 20 patients with suspected CD by capsule endoscopy. The patients had the following features: abdominal pain, weight loss, positive fecal occult blood test, iron deficiency anaemia, diarrhoea and fever. All the patients had normal results in small bowel series (SBS) and in upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy before they were examined. Mean duration of symptoms before diagnosis was 6.5 years.

RESULTS: Of the 20 patients, 13 (65%) were diagnosed as CD of the small bowel according to the findings of M2A Given Capsule. The findings detected by the capsule were mucosal erosions (2 patients), aphthas (5 patients), nodularity (1 patient), large ulcers (2 patients), and ulcerated stenosis (3 patients). The distribution of the lesions was mainly in the distal part of the small bowel, and the mild degree of lesions was 54%.

CONCLUSION: Wireless capsule endoscopy is effective in diagnosing patients with suspected CD undetected by conventional diagnostic methods. It can be used to detect early lesions in the small bowel of patients with CD.

- Citation: Ge ZZ, Hu YB, Xiao SD. Capsule endoscopy in diagnosis of small bowel Crohn’s disease. World J Gastroenterol 2004; 10(9): 1349-1352

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v10/i9/1349.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v10.i9.1349

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a systemic granulomatous disease that may involve any part of the alimentary tract. The small bowel is the affected site in 30%-40% of cases[1]. Recent studies have reported a worldwide rise in the incidence of CD. The “gold standard” for the diagnosis of CD includes the presence of following features: abdominal pain, weight loss, positive fecal occult blood test, iron deficiency anaemia, diarrhoea, fever, and typical evidence of pathological processes on conventional imaging techniques, such as, small bowel X ray, computerized tomography (CT) of the abdomen, enteroscopy, colonoscopy and ileoscopy. The small bowel is the most difficult part to be examined by endoscopy because of its distance from the mouth and anus. Small bowel series (SBS) therefore remains the first line approach in the diagnosis of small bowel Crohn’s disease. When the disease is mild, with inflammatory changes confined to the mucosa, CD lesions can be missed by SBS.

Wireless capsule endoscopy (CE)[2-7] has now made painless imaging of the entire small bowel possible. In some trials, CE proved to have a higher diagnostic yield in patients with suspected small bowel diseases[8-19]. It can be used to detect early lesions in the small bowel of patients with CD. The current study represented our initial experience with the M2A Capsule in diagnosing CD in patients undergone conventional investigations in which no characteristic abnormalities were detected.

From May 2002 to April 2003, we prospectively examined 20 patients with suspected CD by capsule endoscopy. They were 5 women and 15 men, aged 16-78 years (mean 45.2). The had following manifestions such as abdominal pain, weight loss, positive fecal occult blood test, iron deficiency anaemia, diarrhoea and fever. All patients had normal results in SBS and in upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopy within 6 mo before they were examined. Exclusion criteria included a history of bowel obstruction, X ray evidence of small bowel stricture, evidence of any pathological abnormalities of the small bowel, any use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs during the past year.

The pertinent characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. The symptoms of the 20 patients enrolled in the study were consistent with suspected CD. Fourteen had abdominal pain, 13 had positive fecal occult blood test, 10 had iron deficiency anaemia (mean 81 g/L haemoglobin), 4 had diarrhoea, 3 had weight loss, and 2 had fever, some had more than one symptoms. Mean duration of the symptoms before diagnosis was 6.5 years (SD6.5).

| Total patients CD | Patients based on CE | |

| Patients (n) | 20 | 13 |

| Age, yr (mean ± SD) | 45.2 (16-78) | 44.2 (16-78) |

| Sex (%), male/female | 75/25 | 85/15 |

| Positive fecaloccult blood test1 | 13/20 (65) | 11/13 (85) |

| Anaemia 1 (%) | 10/20 (55) | 9/13 (77) |

| Haemoglobin, mean ± SD (g%) | 8.1 (2.0) | 7.8 (1.9) |

| Abdominal pain1 (%) | 14/20 (70) | 7/13 (54) |

| Diarrhoea1 (%) | 4/20 (20) | 2/13 (15) |

| Weight loss1 (%) | 3/20 (15) | 3/13 (23) |

| Fever1 (%) | 2/20 (10) | 2/13 (15) |

| Duration of disease, yr (mean ± SD) | 6.5 (6.5) | 7.0 (7.8) |

Wireless capsule endoscope (CE) (Given M2A, Given Imaging Ltd, Yoqneam, Israel) measures 11 mm × 26 mm, has a battery life of approximately 6-8 h, and is propelled by peristalsis, not requiring air insufflation. CE is used in conjunction with an imaging system which includes a data recorder and interpretive workstation. CE is disposable and contains a complementary metal-oxide semiconductor (CMOS) chip camera, a transmitter, a light-emitting diode (LED) to provide illumination, and silver oxide batteries. Continuous video images were transmitted from the capsule to an antenna worn over the patient abdomen at a rate of two frames per second during passage of the CE through the gastrointestinal tract. The hemispheric lens yielded a 140-degree field of view. During the procedure, approximately 50000 images were recorded by a solid-state recorder that was worn as a belt by the patient. The recorder was later connected to a computer workstation, in which the images were processed and then viewed on a monitor using a specifically designed reporting and processing of images and data (RAPID) software package.

After an overnight fast for 8-12 h, the patients ingested CE with a small amount of water. They were then free to remain active as outpatients. After the study interval, the patients returned to the clinic and the recorded digital information was then downloaded into a computer. Images from the stomach and the length of small bowel were analyzed using the proprietary RAPID software. The images transmitted by the capsule were interpreted by two independent gastroenterologists. All patients were interviewed after completing the study to evaluate the tolerance or complications.

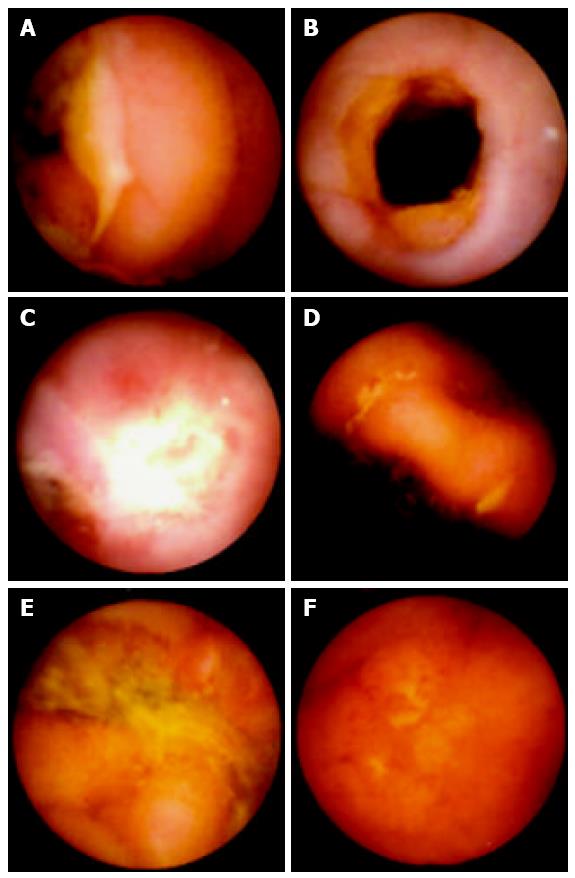

All the 20 patients described that the capsule was easy to swallow, painless, and preferable to conventional endoscopy. No complications were observed. The images displayed were considered to be good (Figure 1). Retention of the capsule was observed in three patients with small bowel stenosis caused by Crohn’s disease (5, 7 and 22 d after capsule ingestion, respectively). One of them had a transient abdominal pain on the third and fourth day after capsule ingestion. None of the three patients with retention of the capsule showed any symptoms of acute or subacute obstruction during the follow-up. The capsule failed to reach the colon in 2 patients during the 8-h acquisition time.

Based on the results of the Given M2A Capsule, we diagnosed CD of the small bowel in 13/20 patients (65%) and normal small bowel mucosa in the remaining 6 of 7 (30%), a jejunal carcinoid confirmed by surgery in the other one. The findings detected by the capsule were mucosal erosions (2 patients), aphthas (5 patients), nodularity (1 patient), large ulcers (2 patients), and ulcerated stenosis (3 patients) (Figure 1). The distribution of the lesions was mainly in the distal part of small bowel (9 in ileum and 2 in the distal part of jejunum) which could not be reached with push endoscopy. The mild lesions or early stages of the disease accounted for 54% (2 mucosal erosions and 5 aphthas). Most of the patients underwent total colonoscopy (16/20), ileoscopy (the ileoscopy succeeded in only five patients) and gastroscopy (20/20). Fourteen out of 20 patients had abdominal CT and all had small bowel X ray series. Some of the patients underwent the procedures more than once. The mean number of procedures undergone previously was 5.4 (SD2.3).

Of the 13 patients who received medications, 11 showed a good clinical improvement after 5-ASA (mean 4 g/d) and a short term steroid treatment while the other two showed some improvement in their clinical symptoms with the same treatment. Follow up ranged from one to eleven months (mean 4 mo).

It is generally accepted that the current visualization and imaging methods available to gastroenterologists in identifying small bowel pathology, particularly inflammatory diseases, were unsatisfactory[19,20].

The reliability of radiological studies is highly influenced by the skill and experience of the operator and how fine is the detail of the mucosa on the film. Neither enteroclysis nor small bowel follow-through (SBFT) X-ray series were able to detect flat mucosal lesions[14,21-23]. CT of the abdomen could not detect mucosal inflammation, it could show transmural thickening and extramural complications but is incapable of discerning CD in early stages of the disease.

Push enteroscopy requires an experienced and skillful endoscopist, the procedure requires between 15 and 45 min and is often uncomfortable for patients. In addition, the instrument could only examine between 80 cm and 120 cm beyond the ligament of Treitz, and occasional complications might occur[24-27].

Sonde endoscopy in theory, has the potential to examine the entire small bowel. The procedure time is often 8 h or longer and can be associated with significant patient discomforts. Among patients referred for Sonde examination, 10% had complications, and up to 75% of the distal ileum was not reached. For these reasons, Sonde- enteroscopy was seldom performed and available in only a few diagnostic centers worldwide[25-28].

Another approach to small bowel imaging is examination of the entire small bowel by intraoperative endoscopy. The limitations of this option were the drawbacks associated with exploratory laparotomy and general anaesthesia[29].

The alternative solution should be relatively comfortable for patients, easy to use by gastroenterologists, and one that could provide a reasonable level of visual imaging for the detection of small bowel abnormalities. The Given diagnostic imaging system (M2A Capsule)[2-7] is a new modality designed to accommodate these requirements.

Capsule endoscopy has now made imaging of the entire small bowel possible. Its indications[30] are obscure gastrointestinal bleeding, abnormal imaging of small intestine, chronic abdominal pain with reasonable suspicion of organic cause in small intestine, chronic diarrhea, evaluation of extent of Crohn’s disease and celiac disease and visualization of surgical anastomoses, surveillance of polyposis syndromes of small intestine.

The cost of the technology per test is about ¥8500. In order to answer what is the cost of capsule endoscopy in comparison with the cost of traditional examinations, one must consider the diagnostic yield and cost-effectiveness of capsule endoscopy compared with traditional diagnostic tools. The diagnostic rate of wireless capsule endoscopy in patients with suspected small bowel diseases was about 70% in our experience[8,9]. It was similar to some other reports and significantly superior to the traditional diagnostic tools[10,19]. The potential for cost savings includes (1) improved diagnostic rate and reduction in reccurrence, conclusive testing associated not only with the clarity of the images obtained by the Capsule, but also with the Capsule’s ability to traverse the entire small bowel (whereas endoscopic examinations leave part of the small bowel unexamined); (2) improved diagnostic precision able to confirm the source of bleeding, and/or rule-out certain etiologies; (3) earlier diagnosis of potentially adverse conditions such as malignancies of the small bowel; (4) reduced complications associated with the diagnostic procedure such as intestinal tears resulting from placement of the enteroscope and/or infection; (5) reduced loss in productivity associated with undergoing testing and repetitive examinations, and reduced loss in quality of life associated with both testing and worry; and (6) reduced pain and discomfort associated with the diagnostic procedures.

A significant advantage of wireless capsule endoscopy is its ability to detect small bowel abnormalities, including those areas not reached by traditional endoscopy. The current battery life of 8 h could allow a reliable examination of the upper GI tract and small bowel in most patients. This was our experience as well because the complete small bowel could be studied in 18 of the 20 (90%) patients (except for the three patients with small bowel stenosis caused by Crohn’s disease). The lesions in the distal jejunum and ileum were identified in 11 of 13 patients (85%) with abnormal capsule endoscopy beyond the reach of push enteroscope.

The only definite contraindication to the procedure is a patient who is a nonsurgical candidate or who refuses to entertain the idea of surgery. A retained capsule then would present the problem of retrieval with laparotomy. Severe motility disorders, including untreated achalasia and gastroparesis, should preclude CE, unless the capsule could be delivered endoscopically to the duodenum[30].

In our study, retention of the capsule occurred in three patients with small bowel stenosis caused by Crohn’s disease and delayed passage of the capsule was observed in two CD patients, possibly because of slow transit time due to the inflamed small bowel mucosa. Although the capsule failed to reach the caecum, we could still identify typical lesions of CD from the recordings that emerged before the battery ran out. The information gained was helpful in further treatment planning for all these patients.

Possible complications existed with any procedure, CE was no exception. The major issue was capsule retention proximal to a stricture. The narrowed area might be anticipated or completely unexpected. Even enteroclysis could not preclude the possibility of a stricture. Our initial experience suggests the capsule does not itself cause intestinal obstruction, but proximal to a stricture it would tumble around and either eventually passes or rarely needs surgical retrieval. A retained capsule usually is asymptomatic and can be detected on the video when reviewed. Plain abdominal films could be obtained after several days to see whether the capsule passed spontaneously. The transient abdominal pain usually signals the passage of the capsule. Barkin et al[31] reported that surgical intervention to remove a non-passed capsule was only 0.75% (7/937). Therefore, capsule endoscopy should not be used in patients with a history of small bowel obstruction or evidence of significant bowel stenosis.

Our study demonstrated a high diagnostic rate in patients with clinical symptoms indicative of CD who had previously undergone several diagnostic procedures that showed normal results. The patients had long intervals from the onset of disease to diagnosis. The wireless capsule might have been able to provide a correct diagnosis during early stages of the disease as well as in cases of less severe forms. We propose the wireless capsule as an effective modality for diagnosing patients with suspected CD.

In conclusion, wireless capsule endoscopy is a valuable diagnostic tool in the evaluation of obscure GI bleeding and a variety of other small bowel disorders. It illustrates the power of innovative technology to advance our diagnostic capabilities that can be applied safely to patients in the outpatient setting. In our opinion, CE should become the initial diagnostic choice in patients with suspected small bowel diseases and negative upper and lower gastrointestinal endoscopic studies.

| 1. | Delaney CP, Fazio VW. Crohn's disease of the small bowel. Surg Clin North Am. 2001;81:137-58, ix. |

| 3. | Gong F, Swain P, Mills T. Wireless endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:725-729. |

| 5. | Fritscher-Ravens A, Swain CP. The wireless capsule: new light in the darkness. Dig Dis. 2002;20:127-133. |

| 6. | Bar-Meir S, Bardan E. Wireless capsule endoscopy--pros and cons. Isr Med Assoc J. 2002;4:726. |

| 7. | Fireman Z, Glukhovsky A, Jacob H, Lavy A, Lewkowicz S, Scapa E. Wireless capsule endoscopy. Isr Med Assoc J. 2002;4:717-719. |

| 8. | Ge ZZ, Hu YB, Gao YJ, Xiao SD. Clinical application of wireless capsule endoscopy. Zhonghua Xiaohua Zazhi. 2003;23:7-10. |

| 9. | Ge ZZ, Hu YB, Xiao SD. An evaluation of capsule endoscopy and push enteroscopy in the diagnosis of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Zhonghua Xiaohua Neijing Zazhi. 2003;20:223-226. |

| 10. | Ang TL, Fock KM, Ng TM, Teo EK, Tan YL. Clinical utility, safety and tolerability of capsule endoscopy in urban Southeast Asian population. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:2313-2316. |

| 11. | Appleyard M, Fireman Z, Glukhovsky A, Jacob H, Shreiver R, Kadirkamanathan S, Lavy A, Lewkowicz S, Scapa E, Shofti R. A randomized trial comparing wireless capsule endoscopy with push enteroscopy for the detection of small-bowel lesions. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1431-1438. |

| 12. | Appleyard M, Glukhovsky A, Swain P. Wireless-capsule diagnostic endoscopy for recurrent small-bowel bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:232-233. |

| 13. | Lewis BS, Swain P. Capsule endoscopy in the evaluation of patients with suspected small intestinal bleeding: Results of a pilot study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:349-353. |

| 14. | Costamagna G, Shah SK, Riccioni ME, Foschia F, Mutignani M, Perri V, Vecchioli A, Brizi MG, Picciocchi A, Marano P. A prospective trial comparing small bowel radiographs and video capsule endoscopy for suspected small bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:999-1005. |

| 15. | Ell C, Remke S, May A, Helou L, Henrich R, Mayer G. The first prospective controlled trial comparing wireless capsule endoscopy with push enteroscopy in chronic gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2002;34:685-689. |

| 16. | Van Gossum A, François E, Hittelet A, Schmit A, Devière J. A prospective, comparative study between push enteroscopy and wireless video capsule in patients with obscure digestive bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:276. |

| 17. | Scapa E, Jacob H, Lewkowicz S, Migdal M, Gat D, Gluckhovski A, Gutmann N, Fireman Z. Initial experience of wireless-capsule endoscopy for evaluating occult gastrointestinal bleeding and suspected small bowel pathology. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2776-2779. |

| 18. | Bardan E, Nadler M, Chowers Y, Fidder H, Bar-Meir S. Capsule endoscopy for the evaluation of patients with chronic abdominal pain. Endoscopy. 2003;35:688-689. |

| 19. | Schreyer AG, Gölder S, Seitz J, Herfarth H. New diagnostic avenues in inflammatory bowel diseases. Capsule endoscopy, magnetic resonance imaging and virtual enteroscopy. Dig Dis. 2003;21:129-137. |

| 20. | Tibble JA, Bjarnason I. Non-invasive investigation of inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:460-465. |

| 21. | Lewis BS. Radiology versus endoscopy of the small bowel. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1999;9:13-27. |

| 22. | Chong AK. Comments regarding article comparing small bowel radiographs and video capsule endoscopy. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:276. |

| 23. | Liangpunsakul S, Chadalawada V, Rex DK, Maglinte D, Lappas J. Wireless capsule endoscopy detects small bowel ulcers in patients with normal results from state of the art enteroclysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:1295-1298. |

| 24. | MacKenzie JF. Push enteroscopy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1999;9:29-36. |

| 25. | Swain CP. The role of enteroscopy in clinical practice. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1999;9:135-144. |

| 26. | Lewis BS. The history of enteroscopy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1999;9:1-11. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Gay GJ, Delmotte JS. Enteroscopy in small intestinal inflammatory diseases. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1999;9:115-123. |

| 28. | Seensalu R. The sonde exam. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 1999;9:37-59. |

| 29. | Delmotte JS, Gay GJ, Houcke PH, Mesnard Y. Intraoperative endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin North Am. 1999;1:61-69. |

| 30. | Ge ZZ, Xiao SD. Prospects for wireless capsule endoscopy. Weichangbingxue. 2002;7:326-330. |

| 31. | Barkin J, Friedman S. Wireless capsule endoscopy (WCE) requiring surgical intervention: The world's experience [abstract]. Berlin: 2nd conference on capsule endoscopy 2003; 171. |

Edited by Zhang JZ, Wang XL Proofread by Xu FM