Published online Apr 28, 2021. doi: 10.13105/wjma.v9.i2.176

Peer-review started: February 2, 2021

First decision: March 8, 2021

Revised: March 13, 2021

Accepted: April 23, 2021

Article in press: April 23, 2021

Published online: April 28, 2021

Processing time: 85 Days and 2.9 Hours

Dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) have emerged as a promising tool with great potential for use in tissue regeneration and engineering. Some of the main advantages of these cells are their multifaceted differentiation capacity, along with their high proliferation rate, a relative simplicity of extraction and culture that enables obtaining patient-specific cell lines for their use in autologous cell therapy. PubMed, Scopus and Google Scholar databases were searched for relevant articles related to the use of DPSCs in regeneration of dentin-pulp complex (DPC), periodontal tissues, salivary gland and craniomaxillofacial bone defects. Few studies were found regarding the use of DPSCs for regeneration of DPC. Scaffold-based combined with DPSCs isolated from healthy pulps was the strategy used for DPC regeneration. Studies involved subcutaneous implantation of scaffolds loaded with DPSCs pretreated with odontogenic media, or performed on human tooth root model as a root slice. Most of the studies were related to periodontal tissue regeneration which mainly utilized DPSCs/secretome. For periodontal tissues, DPSCs or their secretome were isolated from healthy or inflamed pulps and they were used either for preclinical or clinical studies. Regarding salivary gland regeneration, the submandibular gland was the only model used for the preclinical studies and DPSCs or their secretome were isolated only from healthy pulps and they were used in preclinical studies. Likewise, DPSCs have been studied for craniomaxillofacial bone defects in the form of mandibular, calvarial and craniofacial bone defects where DPSCs were isolated only from healthy pulps for preclinical and clinical studies. From the previous results, we can conclude that DPSCs is promising candidate for dental and oral tissue regeneration.

Core Tip: Dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) can be isolated from the pulps of impacted teeth requiring surgical extraction or from teeth extracted for orthodontic reasons. In addition, there is growing evidence that DPSCs can be isolated from inflamed pulps derived from carious teeth with symptomatic irreversible pulpitis. DPSCs are neural crest in origin, and thus they differentiate into an astonishing array of cell types and tissues and regenerate structures that have the same developmental origin, like dentin-pulp complex, periodontal tissues, stromal tissues of salivary glands and craniomaxillo

- Citation: Grawish ME, Saeed MA, Sultan N, Scheven BA. Therapeutic applications of dental pulp stem cells in regenerating dental, periodontal and oral-related structures. World J Meta-Anal 2021; 9(2): 176-192

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2308-3840/full/v9/i2/176.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.13105/wjma.v9.i2.176

The oral cavity is a complex multi-organic structure, where oral tissues and organs are linked developmentally and functionally. Irreversible damage to any of them is more likely to affect the others, causing extensive malfunction. Tooth decay, periodontal diseases, alveolar bone resorption, and impaired salivary gland (SG) function are conditions that seriously affect oral health. Synthetic materials have traditionally been used as the treatment of choice in prosthetic and restorative dentistry. However, this form of replacement does not regenerate the original biological tissues and other organs, such as SGs, are simply not responsive to mechanical substitution approaches. Thus, tissue engineering (TE) is emerging as a new therapeutic choice for the complete biological regeneration of craniomaxillofacial tissues and organs. Three critical components are required: (1) stem cells; (2) scaffolds; and (3) stimulating factors or inductive signals[1].

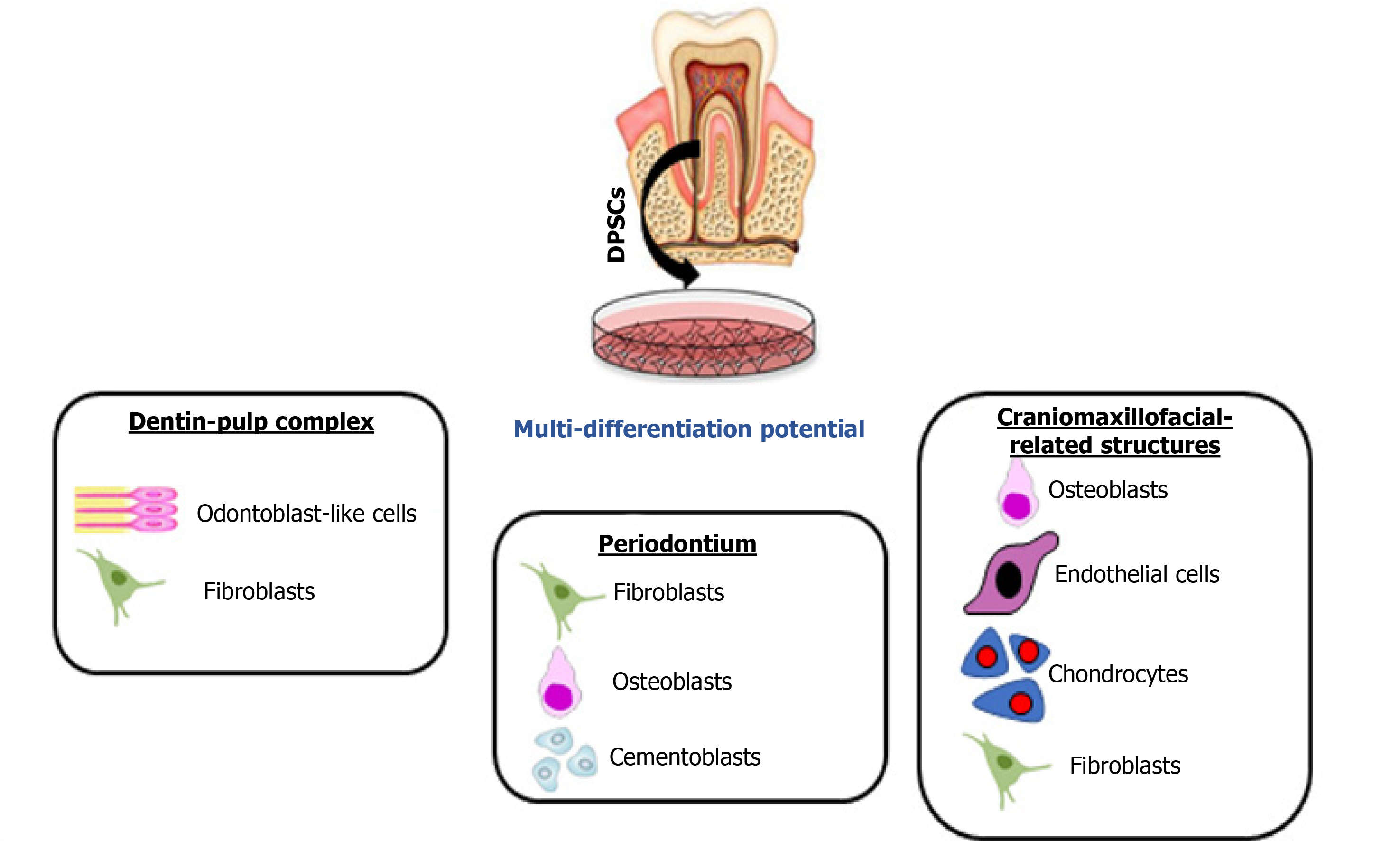

Dental pulp stem cells (DPSCs) are neural crest-derived cells with an excellent ability to differentiate along multiple cell lineages (Figure 1). In particular, simple in vitro protocols can be used to achieve highly efficient osteo/dentinogenic differentiation of DPSCs, making these cells a very attractive and promising tool for the future treatment of dental and periodontal diseases. Among oral-related structures, regeneration of the SGs and bone defects appears to be possible using DPSCs, as researchers over the last decade have made substantial progress in experimental models of partial or total regeneration of both organs[2]. Emerging approaches using cell-free therapy with cell extracts or secretome components also exhibit favorable outcomes and when compared to cell-based approaches, the secretome can be relatively easily obtained, quantified and are more stable for long-term storage to be used in various TE fields[3].

In this review, we explored the potential usage of DPSCs in preclinical and clinical trials for the regeneration of different oral, dental and craniomaxillofacial tissues and organs. Therefore, PubMed, Scopus and Google Scholar databases were searched for relevant articles related to the use of DPSCs in regeneration of dentin-pulp complex (DPC), periodontal tissues, SG and craniomaxillofacial bone defects. We present the different strategies used in experimental regenerative models with potential applications in dentistry and oral medicine. Based on data extraction from the different databases, we can conclude that DPSCs may be an ideal choice to be used in experimental models of tissue-engineered reconstruction of organs of the oral cavity, and the paradigmatic cases of the tooth and the SG may constitute the leading edge of a massive research effort on next generation organ replacement therapies.

Teeth are composed of various dental tissues, viz. enamel, dentin, pulp, and cementum. Dentin and pulp formulate the DPC that preserves tooth viability and integrity[4]. On one hand, the pulp provides dentin with moisture, nutriment, and minerals to keep its resiliency and degree of mineralization; therefore, in the case of pulp necrosis, dentin gets dark and brittle with the sequelae of tooth discoloration and fracture. On the other hand, dentin provides a closed protecting barrier for the pulp against bacterial toxins and physical or chemical irritants; therefore, dentin damage or pulp exposure seriously threaten tooth vitality and integrity[5].

Following carious or traumatic injury to dentine-pulp, a complex interplay between host defense response, inflammatory and infective agents and endogenous repair processes occur. DPC is a difficult structure to manufacture in vitro or repair in vivo or ex vivo. Embryologically, dentinogenesis starts with the secretion and cross basement membrane transport of signaling proteins from the differentiating ameloblasts during the early bell stage of tooth development. Amongst many cytokines and growth factors, the TGFβ is considered to initiate the dentinogenesis process through inducing odontogenic differentiation of the undifferentiated ectomesenchymal cells of the dental papilla[6]. During development and after enamel maturation and tooth eruption, ameloblasts are lost forever; therefore, recreating the dentinogenesis process again in TE without ameloblasts is difficult due to the absence of the initiator. Histologically, the DPC is formed of two different tissues. The outermost layer of the dental pulp (DP) consists of odontoblasts that responsible for the formation of primary, secondary and tertiary dentin throughout life. The odontoblastic processes may extend from the odontoblasts through the whole thickness of dentin and may be embedded in the enamel as enamel spindles, dentin includes various noncollagenous proteins that control the activity of odontoblasts, fibroblasts and DPSCs[7].

Several biomaterials are used to repair the dentin and regenerate DPC, such as calcium hydroxide, adhesive resin cement, mineral trioxide aggregate, Biodentine, and emdogain. Actually, all these materials are developed on empirical bases, rather than on the deep understanding of the histological structure of the DPC or the molecular bases of the pulp self-healing mechanism[8]. Consequently, the results of these previous studies showed the inability of these materials to regenerate the DPC, and only disorganized tissues were formed as a response[9].

The idea of regenerating dentin and pulp tissues is based on recruiting DPSCs via several growth factors and scaffolds, what is known as the biological triad of tissue regeneration. The DPSCs have a crucial role in the dentinogenesis process as they are responsible for the reconstruction of the damaged dentin and pulp. These cells work under the influence of chemical/physical signaling mechanisms that induce stem cell differentiation to express the desired phenotype[10]. DPSCs were successfully tested in preclinical and clinical studies for DPC regeneration.

DPSCs[11-14] and DP progenitor cells[12] have been isolated from permanent teeth pulps. In some instances, the cells were transfected with lentivirus virus-mediated gene transfer of platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)[15]. The strategy of using DPSCs was dependent on scaffold-based and scaffold-free therapies. DPSCs were loaded into the scaffold[12,13] or, incorporated into the scaffold and the combination was injected locally[11,14,15]. Nude mice and minipigs were the most selected model for studying the regenerative effect of DPSCs for DPC regeneration in the pre-clinical trials. The cell number most commonly implicated was 1 × 106[11-13] and an 8 × 106[14] cell number was also used (Table 1).

| Ref. | Strategy | Model | Defect/site of cell implantation | Cell number | Cell source | Cell application |

| Wang et al[11], 2011 | Scaffold-based | Nude mice | Subcutaneous implantation | 1 × 106 | hDPSCs | Loaded on the top surface of the scaffold |

| Pan et al[12], 2013 | Scaffold-based | Nude mice | Subcutaneous implantation | 1 × 106 | DP progenitors | Mixed with collagen sponge sheets and SCF |

| Horibe et al[13], 2014 | Scaffold-based | SCID mice | Subcutaneous implantation | 1 × 106 | hDPSCs | Loaded into human tooth root model |

| Chaudhary et al[14], 2016 | Scaffold-based | Nude mice/ nude rats | Subcutaneous implantation/ first molar root canal | 8 × 106 | hDPSCs | Loaded into rabbit molar pulp cavity/ cell injection into root canals |

| Zhang et al[15], 2017 | Scaffold-base | Nude mice | Subcutaneous implantation | Not detected | hDPSCs | Mixed with porous calcium phosphate cement |

DPSCs-derived from healthy pulp: Loading or injecting a cell suspension of DPSCs. Horibe et al[13] investigated the regenerative capacity of young and aged human (h)DPSCs on ectopic pulp regeneration. They injected 1 × 106 cells combined with pepsin-solubilized collagen solution derived from porcine skin into the human tooth root model prior to subcutaneous transplantation into 5-wk-old severe combined immunodeficiency mice. Evaluation was dependent on histologic and histomorpho

Wang et al[11] seeded 1 × 106 hDPSCs on nanofibrous poly(L-lactic acid) (PLLA) scaffolds, 5.2 mm in diameter and 1.5 mm in thickness. The cell-scaffold constructs were induced in odontogenic media for 2 wk prior to subcutaneous implantation in nude mice with an age 6-8 wk. A cell-scaffold construct cultured in media without odontogenic inducers was used as the control group. The endpoint for this experiment was 8 wk after implantation. The histological examinations of the specimens illustrated formation of new blood vessels and collagen. The immunohistological examin

Pan et al[12] investigated the potential of the DP progenitors to regenerate DPC and, besides, they clarified the efficacy of stem cell factor (SCF) on DP progenitors for odontogenic differentiation and regenerative capability. They mixed 1 × 106 DP progenitors with 3 mm × 3 mm × 3 mm collagen sponge sheets that were coated with 50 ng/mL SCF aqueous solution for a preclinical study. The other groups used in this study were collagen sponges with DP progenitors, collagen sponges with SCF, and collagen sponges only as a control. The cell-scaffold constructs were implanted into the back of male nude mice for 4 wk. After the endpoint of the experiment, the collagen sponges were dissected and prepared for histological examination. The results of this study revealed a high potentiality of the DP progenitors in DPC regeneration. In addition, using the SCF increased the regenerative capacity of DP progenitors.

Chaudhary et al[14] synthesized nanofibrous sponge microspheres (NF-SMS), which were used to carry hDPSCs into the pulp cavity to regenerate living DP tissues. They removed the DP from 16 molars collected from 2-wk-old rabbits. After that, they injected 8 × 106 hDPSCs/NF-SMS complexes pre-cultured under hypoxic condition into the rabbit molar pulp cavities prior to subcutaneous implantation into nude mice with age of 6-8 wk, for 4 wk. The results of this study were evaluated histologically and immunohistochemically. The authors concluded that the hypoxia group significantly enhanced angiogenesis inside the pulp chamber and promoted the formation of odontoblast-like cells lining the dentin-pulp interface, as compared to the control groups, hDPSCs group, NF-SMS group, and hDPSCs/NF-SMS group pre-cultured under normoxic conditions.

Zhang et al[15] explored the influence of the PDGF-BB on hDPSCs proliferation and odontogenic differentiation. They established a PDGF-BB gene-modified hDPSCs using lentivirus delivery vector. The genetically-modified hDPSCs were mixed with a porous calcium phosphate cement scaffold and implanted subcutaneously in nude mice for 12 wk. DPC regeneration was evaluated using histological and immunohis

In another experiment, Chaudhary et al[14] used the maxillary first molars of the nude rats as an in situ pulp regeneration model. The entire pulp was removed and the root canals were cleaned and shaped using manual #15-#25 K files. After irrigation with phosphate-buffered saline and 2.25% NaClO and drying the root canals with absorbent points, 8 × 106 hDPSCs/NF-SMS complexes primed under hypoxic conditions were injected into the prepared root canals, while those primed under normoxic conditions were injected into prepared contralateral first molar root canals. After 4 wk, the treated maxillary molars were harvested. For comparison, maxillary first molars received no treatment after pulp removal. The histological and immunohistochemical analyses of the specimens revealed that the hypoxia-primed hDPSCs/NF-SMS could fully fill the molar canals through injection and promoted pulp-like tissue formation with intimate integration with the native dentin.

The periodontal tissues include two hard and two soft tissues. The two soft tissues are periodontal ligament and gingiva, while the two hard ones are alveolar bone lining the socket and cementum. The principal function of these structures is investing and supporting the teeth to perform their physiologic function. The most common cause for tooth loss in adults is the periodontitis, affecting 10%-15% of adults worldwide as an advanced type. Treatment modalities such as bone grafts[16], enamel matrix derivative[17], platelet-rich plasma (PRP)[18], and guided tissue regeneration[19] allow partial improvements in the architecture and function of the periodontal tissues but fail to completely regenerate this complex structure. Procedures attempting to regenerate the periodontal apparatus have become unconventional and more advanced to include dental tissue-derived stem cell therapy[20]. Chiefly, there are two approaches for periodontal tissues regeneration, cell-based and cell-free therapies. The major concern for the cell-based therapy is the complicated implantation process and it includes stem cell injection of cell suspension and stem cell sheet transplantation techniques. Engineering of a cell sheet has been adopted through utilizing cell culture dishes of temperature-responsive surfaces[21], or by culturing the cells in ascorbic acid[22]. Even though cultured cells can be used to study the pathogenesis of the inflammatory and immune pathways of periodontal diseases, the complicated host defense system basically responsible for these diseases is not amenable to being reproduced in vitro. Experimental periodontitis is a preclinical in vivo model for studying the possible application of cell therapies and biomaterials-targeted for periodontal tissues regeneration. They were considered to be more appropriate mimicking the natural host immune response under microbial loads, which can cause oral pathological environments and periodontal diseases[23]. Animals like nonhuman primates, rodents, rabbits, pigs, and dogs have been selected for modeling human periodontitis. Commonly, periodontitis has been induced by placing a silk ligature inside gingival sulcus around the molar teeth to serve as a retentive factor for plaque and microbial proliferation. In addition, alveolar bone loss has been induced by injection or inoculation of human oral bacteria[24]. DPSCs were successfully tested in preclinical and clinical studies for periodontal tissues regeneration.

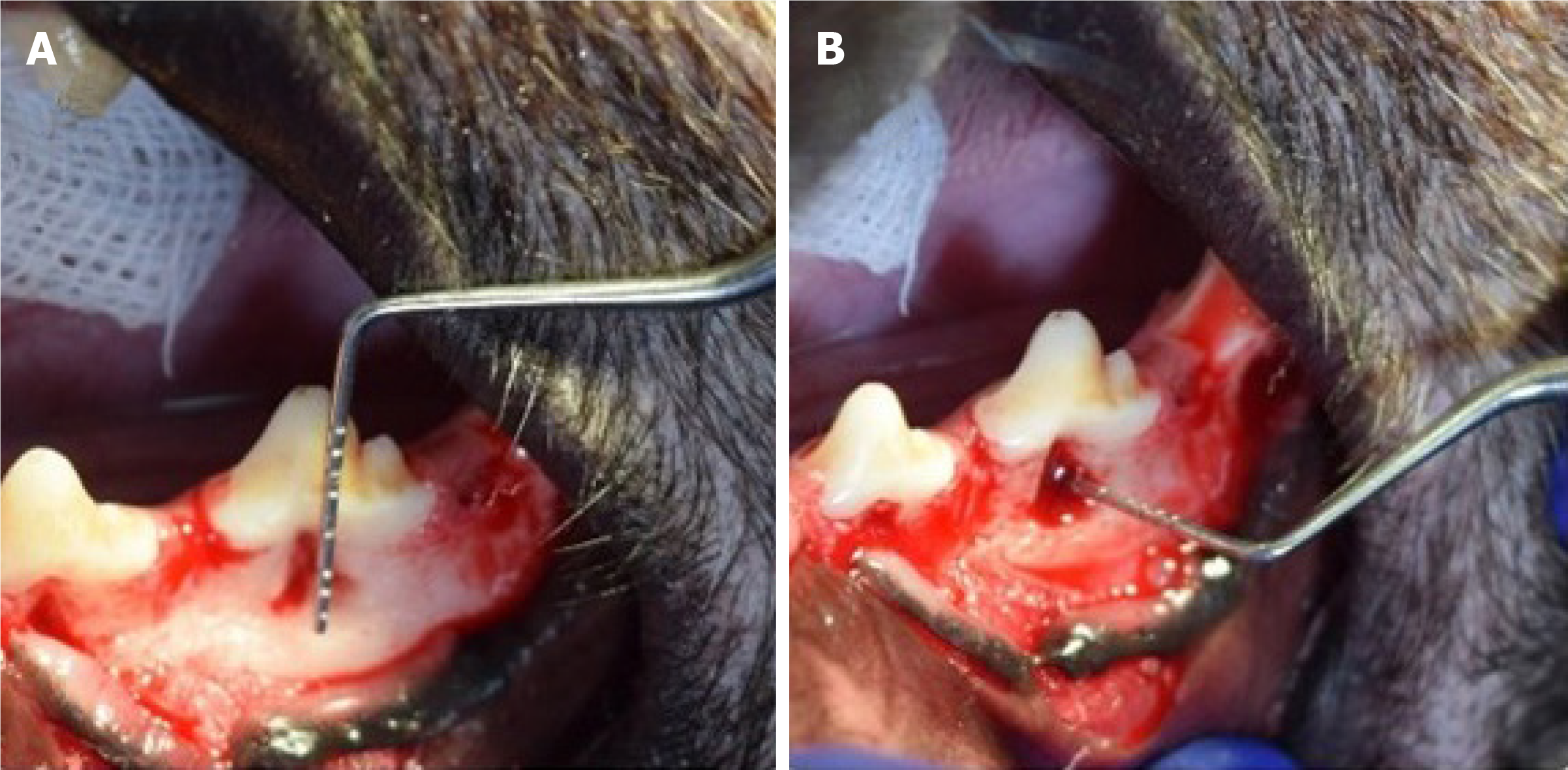

Xenogeneic and autologous[25-32] DPSCs or their exosomes (Exo)[32] have been isolated from healthy[25-28,30-32] or inflamed pulps[29]. In some instances, the cells were transfected with adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)[27]. The strategy of using DPSCs was dependent on scaffold-based[25,29,30,32], sandwich structure[31], scaffold-free[26-28] and cell-free[32] therapies. Application of DPSCs was in the form of cell injection[26-28,30], cell sheet transplantation[27,28,31], loaded onto the scaffold[25,29] or, incorporated onto the scaffold and the combination was injected locally[32]. Miniature pigs were the most selected model for studying the regenerative effect of DPSCs for periodontal tissues regeneration in the pre-clinical trials[26-29]. Other animals such as rats[30], mice[31,32] and dogs[25] were also selected for the same purpose. Bone defects of 5 mm width, 7 mm length and 3 mm depth[26,27] and of 5 mm × 6 mm × 5 mm[28] were the most common surgical periodontal defect models created as a site of cell implantation (Figure 2). Ligature-induced periodontitis with three-walled periodontal defects (PDs)[25], PDs adjacent to the root of the second molars[29], periodontitis created using 5-0 silk ligature[32] were also applied as models. Bioroot regeneration was accomplished through subcutaneous transplantation of a sandwich structure constituted by hDPSCs sheet, human treated dentin matrix (hTDM)/hDPSCs and Matrigel/hDPSCs[31]. The cell number of 1 × 107 was the most commonly implicated[26-29], and 5 × 105[31], 2 × 106[30], 2 × 107[25] cell numbers were also used; in addition, 50 µg[32] of hDPSCs-Exo was indicated for the cell-free therapy strategy (Table 2).

| Ref. | Strategy | Model | Defect/site of cell implantation | Cell number | Cell source | Cell application |

| Khorsand et al[25], 2013 | Scaffold-based | Mongrel dogs | 3-walled PDs with ligature induced periodontitis | 2 × 107 | Autologous dogs' DPSCs | Loaded on the top surface of the scaffold |

| Ma et al[26], 2014 | Scaffold-free | Miniature pigs | Bone defect of 5 mm width, 7 mm length, and 3 mm depth | 1 × 107 | hDPSCs | Cell injection |

| Cao et al[27], 2015 | Scaffold-free | Miniature pigs | Bone defects of 5 mm width, 7 mm length, and 3 mm depth | 1 × 107 | hDPSCs transfected with adenovirus-mediated transfer of HGF gene | Cell sheet transplantation or cell injection |

| Hu et al[28], 2016 | Scaffold-free | Miniature pigs | Bone defect of 5 mm width, 7 mm length, and 3 mm depth | 1 × 107 | hDPSCs | Cell sheet transplantation or cell injection |

| Li et al[29], 2019 | Scaffold-based | Miniature pig | Periodontal defect of 5 mm × 6 mm × 5 mm | 1 × 107 | Autologous pig DPSCs-IPs | loaded onto the scaffold |

| Lin et al[30], 2020 | Scaffold-based | Sprague-Dawley rats | Periodontal defect adjacent to the root of the second molars | 2 × 106 | hDPSCs | Cell injection |

| Meng et al[31], 2020 | Sandwich structure | Nude mice | Subcutaneously (bioroot regeneration) | 5 × 105 | hDPSCs | Cell sheet |

| Shen et al[32], 2020 | Scaffold-based/cell-free therapy | Mouse | Periodontitis created using 5-0 silk ligature | 50 μg | hDPSCs-Exo | Incorporated onto the scaffold and combination injected locally |

| Li et al[33], 2016 | Scaffold-based | Human | Periodontal intrabony defects | 1 × 105 | Autologous DPSCs-IPs | Loaded onto the scaffold material |

| Ferrarotti et al[34], 2018 | Scaffold-based | Human | Chronic periodontitis with deep intrabony defect | 50 μm micrograft | Micrografts rich in autologous hDPSCs | Seeded onto the scaffold |

| Aimetti et al[35], 2018 | Scaffold-based | Human | Chronic periodontitis with deep intrabony defect | 50 μm micrograft | Micrografts rich in autologous hDPSCs | Loaded on the scaffold |

| Hernández-Monjaraz et al[36], 2020 | Scaffold-based | Human | PDs, without uncontrolled systemic chronic diseases | 5 × 106 | hDPSCs | Dripped suspended in 200 mL of PBS and then collagen membrane was placed |

DPSCs-derived from healthy pulp: (1) Loading or injecting a cell suspension of DPSCs. In a scaffold-based trial, Khorsand et al[25] surgically created three-walled PDs with ligature-induced periodontitis in 10 mongrel dogs. The PDs were produced bilaterally at the bone adjacent to the mesial surface of the mandibular first premolar teeth. They investigated the regenerative capacity of autologous dogs' DPSCs on periodontal tissues, with/without Bio-Oss granules. Four weeks after making the periodontitis model, Bio-Oss was engrafted on one side and considered as a control, while on the other side, a combination of 2 × 107 autologous DPSCs of passage 3 with Bio-Oss was engrafted and served as the test group. Evaluation was dependent on histologic and histomorphometric analyses, 8 wk after surgery, in terms of cementum, periodontal ligament, and bone formation. The authors concluded that a biocomplex consisting of Bio-Oss scaffold and DPSCs would be advantageous in regeneration of periodontal tissues. Moreover, Lin et al[30] investigated the regenerative and therapeutic effects of a daily dose, intragastrically administered 25 mg/kg of 2,3,5,4′-tetrahydroxystilbene-2-O-β-d-glucoside (THSG)-triggered hDPSCs in the healing of experimental PDs adjacent to the roots of the second molars in male Sprague-Dawley rats. THSG is a water soluble and biologically active component of the Chinese herbal medicine Polygonum multiflorum. The defects of the negative control were treated with Matrigel, while the defects of the positive control received 2 × 106 hDPSCs/ Matrigel (vol/vol = 3:1). It was found that THSG revolutionized hDPSCs significantly and shortened the regenerative period of PDs by enhancing new bone formation and increasing expression levels of osteopontin, vascular endothelial growth factor, and proliferating cell nuclear antigen than those in other groups.

In a scaffold-free trial, Ma et al[26] evaluated the injection of DPSCs or bone marrow stem cells (BMSCs) for in vivo periodontal regeneration. The investigators created 12 PDs of 3 mm depth, 7 mm length, and 5 mm width in miniature pigs' interradicular bone of the first molars. The defects were divided into three groups, namely DPSCs, BMSCs and control group, each with four defects. The BMSCs and DPSCs groups were separately injected with approximately 1 × 107 human cells in 0.6 mL of 0.9% NaCl, while the defects of the control group were injected with 0.9% NaCl as the cell injection group. Lymphocyte infiltration and impaired sulcular epithelia were evident in the control group but not in the DPSCs and BMSCs groups. Notably, the periodontal bone regeneration capacity was significantly greater for the DPSCs injection group compared to the BMSCs group.

(2) Cell sheet transplantation technique of DPSCs. In a scaffold-based trial, Meng et al[31] created a sandwich structure of hDPSCs sheet/hTDM/Matrigel to be subcutaneously transplanted in nude mice for 3 mo. The main objective was to investigate the regeneration potential of hDPSCs, and the characteristics of the above materials for the tooth root regeneration (bioroot). The hDPSCs sheet was obtained by seeding 5 × 105 hDPSCs in a culture dish containing complete medium supplemented with 20.0 μg/mL vitamin C. The hTDM was fabricated from healthy extracted teeth and a disk with 5 mm thickness was prepared to be successively decalcified and sterilized. The hTDM/hDPSCs complex was prepared by seeding hDPSCs on hTDM and cultured in vitro for 2 d, and the Matrigel/hDPSCs suspension was injected into the complex’s pulp cavity. It was concluded that hDPSCs could be used as seed cells for the whole tooth root regeneration, and the sandwich structure constituted by hDPSCs sheet, hTDM/hDPSCs and Matrigel/hDPSCs could be utilized for tooth root regeneration.

In a scaffold-free trial, Cao et al[27] created 40 PDs of 3 mm depth, 7 mm length, and 5 mm width in miniature pigs, in the mesial region of the mandibular and maxillary first molars. Under good manufacturing practice, hDPSCs were transfected with adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of HGF to evaluate their potential roles for periodontal tissues regeneration. They found that injecting HGF-hDPSCs could significantly improve soft tissue healing and periodontal bone regeneration. In comparison to the injection of dissociated cells, HGF-hDPSCs and hDPSCs sheets showed superior periodontal tissue regeneration. The authors attributed their findings to an increase in blood vessel regeneration and a marked decrease of hDPSCs apoptosis caused by adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of HGF. They concluded that sheets are more suitable for the surgically-managed periodontitis treatments, as they required surgical placement. Moreover, Hu et al[28] created 24 PDs of 3 mm depth, 7 mm length and 5 mm width in the mesial region of the mandibular and maxillary first molars of miniature pigs. The hDPSCs were applied using techniques of cell sheet transplantation or cell injection. The complete form of a morphologically cell sheet was produced by inducing hDPSCs with 20.0 μg/mL vitamin C. The cells of the cell sheet contacted with each other tightly and contained five or six layers. Both cell sheet transplantation and hDPSCs injection significantly regenerated soft tissues and periodontal bone. Compared with hDPSCs injection, the hDPSCs sheet had more bone regenerative capacity.

Finally, (3) secretome-derived from DPSCs. In a scaffold-based trial, Shen et al[32] created a periodontitis mouse model using 5-0 silk ligature tied around the maxillary left second molar to evaluate the effect of chitosan (CS) hydrogel incorporated with hDPSCs-derived Exo. For Exo treatment, an equal volume of phosphate-buffered saline /CS, hDPSCs-Exo (50 μg), and hDPSCs-Exo/CS was injected locally after ligature removal. It was found that treatment with hDPSCs-Exo/CS alleviated periodontitis via macrophage-dependent mechanism through miR-1246. hDPSCs-Exo facilitated the way for the macrophages to be converted from a pro-inflammatory phenotype to an anti-inflammatory phenotype, and suppressed periodontal inflammation and modulated the immune response.

DPSCs-derived from inflamed pulp: In a scaffold-based trial, Li et al[29] cultured an autologous miniature pig DPSCs derived from inflammatory dental pulp tissues (IPs). The cells were characterized and loaded onto β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP) biomaterial. The compounds were then engrafted into artificially-created PDs of 5 mm × 6 mm × 5 mm in the buccal region of root furcations of the third premolars and first molars. Compared to the β-TCP and control groups, DPSCs-IPs expressed moderate to high levels of CD146 and STRO-1 as well as low levels of CD45 and CD34. The cells have chondrogenic, adipogenic, and osteogenic differentiation abilities and when they were engrafted onto β-TCP, they regenerated bone of the PDs through 3 mo post-surgical reconstruction.

Autologous hDPSCs-IPs[33], micrografts rich in autologous hDPSCs[34,35] or autologous hDPSCs derived from healthy pulps[36] were the source for a randomized clinical trial (commonly referred to as RCT)[34], a 1-year follow-up case series[35], a quasi-experimental study[35] and a pilot study[33]. The strategy of using DPSCs was dependent on scaffold-based only[33-35] as they loaded onto the scaffold[33-35] or dripped suspended in 200 mL of phosphate-buffered saline and then the scaffold membrane was placed[36]. Patients diagnosed with combined periodontal-endodontic lesions with pocket depth from 5 mm to 6 mm[33], patients with chronic periodontitis combined with deep intrabony defects[34,35], and patients with controlled chronic diseases and without horizontal PDs or osteoporosis[36] were the models used for cell implantation. Either 1 × 105[33] or 5 × 105[36] and 50 µm micrografts rich in autologous hDPSCs were the cell number/source that was indicated for the scaffold-based strategy (Table 2).

DPSCs-derived from healthy pulp: In a scaffold-based trial, Ferrarotti et al[34] performed a RCT for 29 consecutively enrolled patients with chronic periodontitis presenting one deep intrabony defect and requiring extraction of one vital tooth. They randomly allocated the defects to two groups, test or control ones. They prepared micrografts rich in autologous DPSCs from the DP of the extracted teeth through mechanical dissociation. With the use of minimally invasive surgical technique, the test sites were packed with micrografts seeded onto collagen sponge, whereas the control sites were filled with collagen sponge alone. Their findings exhibited a significantly more probing depth reduction, clinical attachment level gain and bone defect fill in the test sites compared to control ones. It was found that application of DPSCs significantly improved clinical parameters of periodontal regeneration at 1 year after treatment. In addition, Aimetti et al[35] performed a case series with 1-year follow-up for 11 patients with chronic periodontitis superimposed by 11 isolated intrabony defects to explore the potential clinical benefits of the application of DPSCs in the regenerative treatment of deep intrabony defects. Extraction was performed for malposed/impacted teeth to be used as autologous source for DPSCs. The defects were accessed with a minimally invasive flap and filled with DPSCs loaded on a collagen sponge. After 1 year posttreatment, a clinical attachment level gain associated with probing depth reduction and a notable stability of the gingival margin was detected using clinical outcomes supported by the radiographic analysis. In 63.6% of the experimental sites, complete pocket closure was achieved. Moreover, a quasi-experimental study was conducted by Hernández-Monjaraz et al[36] for 22 adults with PDs, without uncontrolled systemic chronic diseases. Every participant underwent clinical and radiological evaluations and saliva samples were taken to determine the total concentration of interleukins (ILs), antioxidants, lipoperoxides, and superoxide dismutase (SOD). All subjects underwent curettage and periodontal surgery and then two groups were allocated randomly, namely experimental and control groups. The defects of the control group had a collagen scaffold, while the experimental one had a collagen scaffold treated with DPSCs. The experimental group showed an increase in the bone mineral density of the alveolar bone with a borderline statistical significance. Regarding inflammation and oxidative stress markers, IL1β levels had a level decrease, while salivary SOD level was significantly higher in the experimental group. Their findings suggest that treatment based on DPSCs has both an effect on bone regeneration linked to an increased SOD and decreased levels of IL1β in subjects with PDs.

DPSCs-derived from inflammatory pulp: In a scaffold-based trial, Li et al[33] harvested DPSCs-IPs from 2 patients with periodontal intrabony defects and then they were loaded onto the scaffold material β-TCP and engrafted into the PD area in the root furcation. At 9 mo after surgical reconstruction, DPSCs-IPs were able to engraft and had an effect of regeneration of new bones to repair PDs. The success rate of primary cell culture and growth status was marginally inhibited; however, DPSCs-IPs expressed comparable levels of stem cell markers as well as retaining their ability to multi-differentiate.

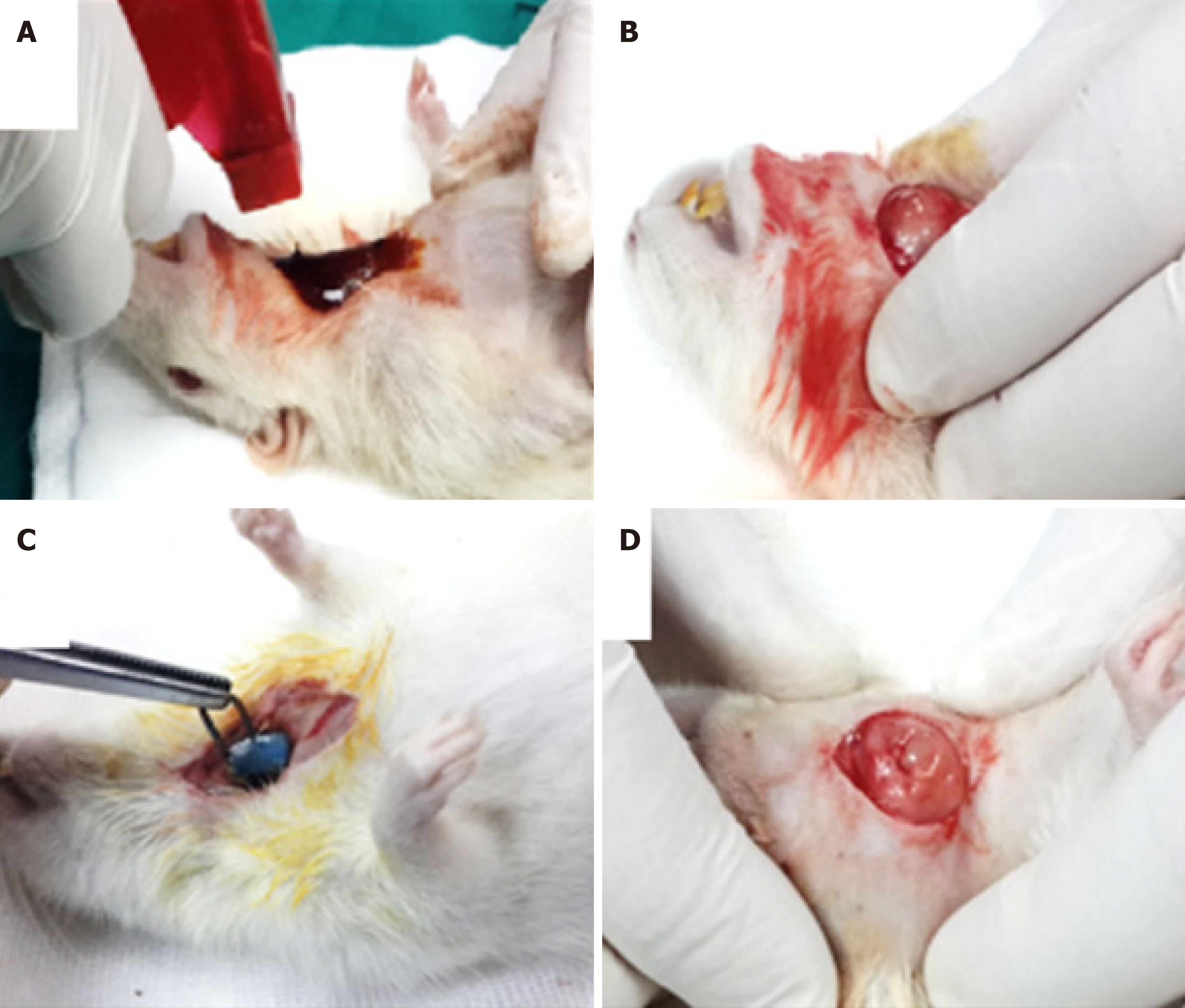

The parotid, submandibular (SMG) and sublingual glands are the three pairs of major SGs. The anatomical architecture of all three glands is virtually identical, with different ratios of serous and mucous cells: an arborized ductal system that opens into the oral cavity with secretory end pieces, or the acini-producing saliva. The acinar cells are surrounded by an extracellular matrix, myoepithelial cells, myofibroblasts, immune cells, endothelial cells, stromal cells and nerve fibers. The ducts transport and modify the saliva before it is excreted into the oral cavity through the excretory duct[37]. The aim of regenerative medicine is to replace/regenerate the SG epithelium and restore its secretory function in patients suffering from permanent loss of major SG function, after radiotherapy of head and neck cancer, which is the sixth most common cancer in the world and affects tens of thousands of new patients every year, causing hyposalivation/xerostomia with subsequent difficulties in mastication, swallowing, taste, speech, high patient discomfort and a reduced quality of life. Palliative therapies show a limited effectiveness in relieving the symptoms, such as mechanical stimulation of SG activity using chewing gum, or pharmacological agents such as pilocarpine, as well as saliva substitutes[38]. Adult stem cell transplantation strategies have recently shown to enhance clinical outcomes in radiotherapy-induced xerostomia in rodents. Mesenchymal stem cells from adipose tissue are the most promising[39], while those from the labial mucosa, bone marrow or DP have an attractive therapeutic value following successful findings in ex vivo and in vivo mouse models of SG injury. DPSCs are supposed to be a good source for SG regeneration by being a component of epithelial acinar cells itself or by being a SG mesenchymal component to encourage and support the regeneration process of the SGs. In SG bioengineering, the principal role of DPSCs is to regenerate the salivary stroma or mesenchymal-derived compartment, and these cells are one of the best choices for that purpose because the tooth mesenchyme and the SG mesenchyme share a common neural crest embryonic origin[40]. A radiation model was developed to reproduce the hyposalivation induced by head and neck cancer therapy. The ductal ligation model aimed to mimic the obstructive sialadenitis and sialithiasis-induced sialopathy and tissue punch considered as a model of mechanical injury (Figure 3). Systemic disease/medication was devised to correspond to Sjogren’s syndrome[41].

Autologous[42,43], xenogeneic[44] DPSCs or their Exo[45] have been isolated from healthy[42-45] DP. The strategy of using DPSCs was dependent on scaffold-based[42], scaffold-free[43,44] and cell-free[45] therapies. Application of DPSCs was in the form of cell injection[42-44]. Mice were the most selected model for studying the regenerative effect of DPSCs for SG regeneration in the pre-clinical trials. Other animals such as rat[43] were also selected for the same purpose. Irradiation-induced SG hypofunction[43] and duct ligation-induced atrophy[45] or salivary hypofunction induced by diabetes[44] were the presented study models. The cell number of 1 × 106 was the most commonly used[42,43] but 5 × 105[44] cell number was also used, and 0.4 mL[45] of DPSCs-CM was indicated for the cell-free therapy strategy (Table 3).

| Ref. | Strategy | Model | Defect/site of cell implantation | Cell number | Cell source | Cell application |

| Janebodin et al[42], 2012 | Scaffold-based | Rag1 null mice | Injected ventrally onto SMG without penetrating the gland | 1 × 106 | Murine DPSCs | 100 μL of cell suspension |

| Yamamura et al[43], 2013 | Scaffold-free | C57BL/6J green fluorescent protein-expressing mice | Irradiated SMG | 2 × 106 | Murine DPSCs | 5 μL of single cell suspension was injected intraglandular using a 28 G needle and microliter syringe. |

| Narmada et al[44], 2020 | Scaffold-free | Wistar rats | SMG of diabetic rat model | 5 × 105 | hDPSCs | Intraglandular cell injection. |

| Takeuchi et al[45], 2020 | Cell-free | ICR mice | SMG duct ligation | 0.4 mL | hDPSCs | DPSCs-CM was administered via the right jugular vein biweekly under general anaesthesia. |

DPSCs-derived from healthy pulp: (1) Subcutaneous and intraglandular injection of cell suspension of DPSCs. In a scaffold-based trial, Janebodin et al[42] created an in-vivo model to study the differentiation effect of DPSCs to support SG tissue formation. They subcutaneously transplanted either 1 × 106 hSG cells alone or 1 × 106 hSG cells combined with 1 × 106 murine DPSCs. These cells were transplanted with hyaluronic acid (HA) hydrogel scaffold into 2-mo-old male Rag1 null mice to avoid immune rejection against hSG. The cells were injected ventrally onto SMG without penetrating the gland in the form of 100 μL of cell suspension. After 2 wk of transplantation, HA plugs were dissected without involving mouse recipients’ SG tissues, to be investigated with hematoxylin and eosin, periodic acid Schiff and immunofluore

In a scaffold-free trial, Yamamura et al[43] established a mouse model in which DPSCs were used as a cell source for treatment of irradiation-induced SG hypofunction. DPSCs were isolated from female C57BL/6J green fluorescent protein-expressing mice and were differentiated into dental pulp endothelial cells (DPECs). Both SMG of the irradiated mice were injected with 1 × 106 DPECs/gland. Eight weeks after irradiation, the effect of DPECs on saliva secretion was evaluated by measuring amounts of saliva secretion. It was found that transplantation of DPSCs are highly effective in maintaining saliva production after irradiation through direct differentiation of into salivary epithelial cells. This study established a mouse model in which DPSCs could be used as a cell source for the treatment of SG hypofunction. Moreover, Narmada et al[44] injected intraglandular tissues of the SMG in diabetic Wistar rat models once with 5 × 105 cells of hDPSCs/250 g in 0.2 mL phosphate-buffered saline solution. The control diabetic rats were injected only with 0.2 mL of phosphate-buffered saline intraglandular. Half of the rats was sacrificed after 7 d, while the remaining rats were sacrificed after 14 d for immunohistochemical evaluation. It was found that transplantation of DPSCs was able to regenerate SMG defects in diabetic Wistar rats by decreasing acinar cell vacuolization.

(2) Secretome from DPSCs. Takeuchi et al[45] collected cell culture supernatant from subconfluently DPSCs culture (DPSC-CM). DP tissues were collected from healthy teeth extracted from individuals. The SMG duct was ligated approximately 2 mm superior to the main body of the gland with a sugita titanium aneurysm clip. The experimental groups were divided into a DMEM group (in which 0.4 mL DMEM was administered via the right jugular vein biweekly) and a CM group (in which 0.4 mL DPSC-CM was administered using a similar method); the control group was composed of mice that underwent only the release of ligation. Injection of DPSCs-CM to mice after releasing the SMG main duct ligation significantly elevated the expression levels of precursor cell marker CK5 and acinar cell marker AQP5 after the release. Growth factors contained in DPSCs-CM were considered to be responsible for the effects. This study suggested that DPSCs-CM administration to mice after releasing the SMG main duct ligation may promote acinar cell regeneration of atrophied SGs.

Bone fractures appear to occur more often in old age because of bone weakening due to a reduction in calcium content in extracellular matrix and slowing of bone remodeling processes. Current methods of treatment are unable to fully reconstruct bone defects that are caused by fractures, tumors and congenital abnormalities. At present, autogenous or allogeneic bones and artificial materials are used for bone augmentation. However, there are various problems with these grafts, such as the possibility of infection or absorption as well as ethical issues. Alternatively, the periosteum and the bone marrow are considered rich in bone progenitors, so that the bone, since early 1990s, has been one of the approachable goals of clinical TE[46]. In addition, osteogenic differentiation of DPSCs is easily induced in vitro by adding ascorbic acid, dexamethasone, and β-glycerophosphate to the culture medium, along with fetal bovine serum, making these cells a promising tool for bone regenera

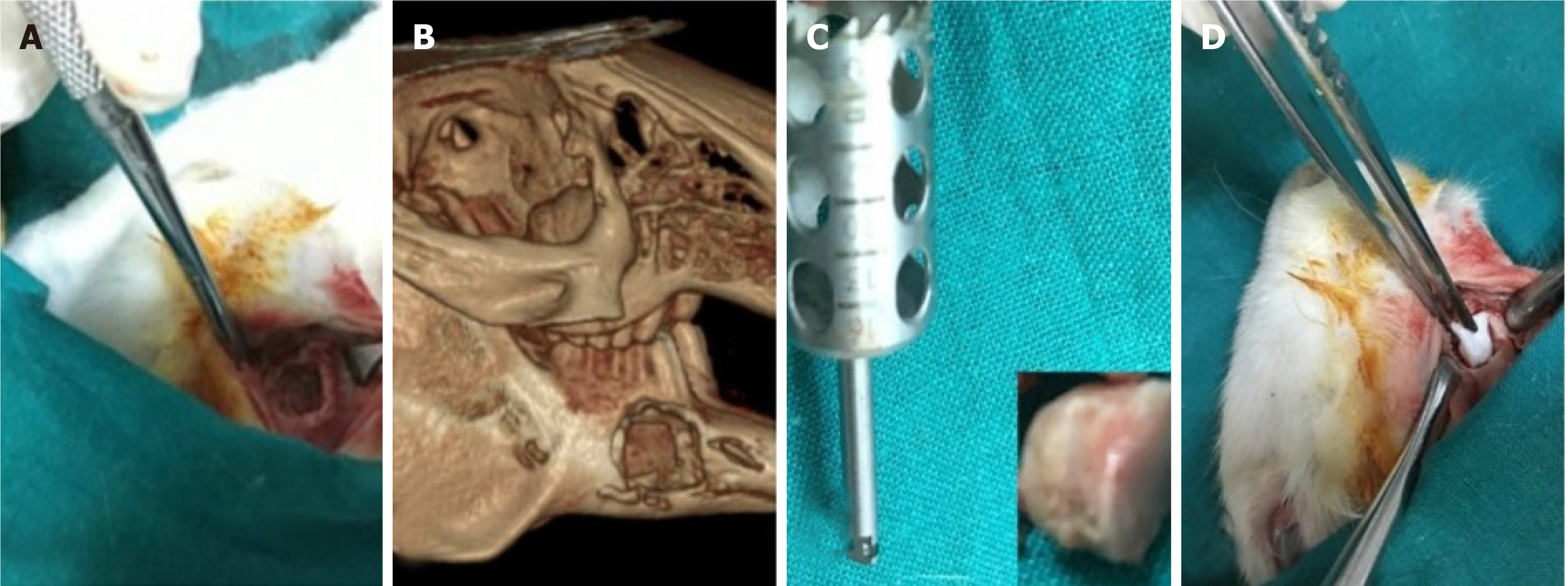

Autologous[51] or xenogeneic[49,50,52] DPSCs have been isolated from healthy[50-52] DP. The strategy of using DPSCs was dependent on scaffold-based[52], scaffold-free[50,51] therapies. Application of DPSCs was in the form of cell sheet transplantation[51], loaded onto the scaffold[52] or, incorporated onto the PRP and the combination was injected locally[50]. Animals such as rabbit[52], mice[51] and dogs[50] were selected to study bone regeneration preclinically. Mandibular[50] (Figure 4), calvarial[51] and craniofacial[52] bone defects were presented. The cell number of 1 × 107 was the most commonly implicated[50] but 2 × 106[52] was also used (Table 4).

| Ref. | Strategy | Model | Defect/site of cell implantation | Cell number | Cell source | Cell application |

| Yamada et al[49], 2010 | Scaffold-free | Dogs | Mandibular bone defects were prepared using a trephine bur with a diameter of 10 mm | 1 × 107 | hDPSCs | Cavities filled with DPSCs/PRP |

| Liu et al[50], 2011 | Scaffold-based | Rabbit | A segmental critical size defect (10 mm × 4 mm × 3 mm) was prepared in the alveolar bone | 1 × 106 | Autologous DPSCs | DPSCs were seeded onto nano- hydroxyapatite/collagen/PLLA and implanted in-vivo |

| Fujii et al[51], 2018 | Scaffold-free | Mice | 3.5 mm calvarial defects | NA | Autologous DPSCs | Cell sheet transplantation |

| Mohammed et al[52], 2019 | Scaffold-based | Rabbit | Craniofacial bone defect in the left side of TMJ | 2 × 106 | hDPSCs | DPSCs were loaded on gel foam |

| Chamieh et al[53], 2019 | Scaffold-based | Rat | Non-critical defects of the tibia in rats | 106 cells/mL | hDPSCs | Loaded on a lyophilized and hydrolyzed collagen sponge (Hemospon®) |

| d’Aquino et al[54], 2009 | Scaffold-based | Human | Defect without walls, of at least 1.5 cm in height | 1 × 107 | Autologous DPSCs | Cells endorsed with a syringe onto collagen sponge scaffold |

DPSCs-derived from healthy pulp: (1) Loading or injecting a cell suspension of DPSCs. In a scaffold-based trial, Mohammed et al[52] loaded 2 × 106 hDPSCs on gel foam scaffold to be fitted in induced temporomandibular joint defect area of 2.5 mm × 2.5 mm in diameter and in depth for the rabbit’s mandible. The histological investigation was performed for qualitative evaluation of bone healing and it was found that newly formed bone with thick trabecular pattern and less osteoid tissue have been observed in the experimental rabbits transplanted with osteogenic-differentiated hDPSCs. The authors suggested the ability of transplanted osteogenic differentiated hDPSCs to produce new osteoid tissue that helps in repairing an induced rabbit mandibular defect in a time and differentiation phase-dependent manner. In an attempt to confirm that bone regeneration was indeed the function of hDPSCs, Chamieh et al[53] tested the efficacy of DPSCs seeded on a collagen scaffold for craniofacial bone regeneration. Plastically compressed collagen gels were loaded with DPSCs (2 × 106 cells/mL) which were isolated from molar Wistar rats. A 5-mm diameter calvarial critical-sized defect was created on each side of the parietal bone using a dental bur attached to a slow-speed hand piece operating at 1500 rpm, under irrigation with sterile saline solution; empty defects were created as a negative control for the critical-sized defects. It was found that collagen gel scaffolds seeded with DPSCs improved bone healing and the remodeling process under micro-X-ray computed tomography as well as histological examination.

Liu et al[50] utilized nano-hydroxyapatite/collagen/PLLA as a scaffold for autologous DPSCs seeding to reconstruct critical-size alveolar bone defects in New Zealand rabbit. A 10 mm incision was made and the tissue overlying the diaphysis of the left alveolar bone of incisors of rabbits was dissected. A segmental defect of 10 mm × 4 mm × 3 mm was prepared in the alveolar bone. Cell number of 1 × 106 DPSCs was implanted onto the scaffold and transplanted into the alveolar bone defect. The animals were sacrificed 12 wk after operation for histological observation and histomorphometric analysis. It was found that reconstruction of alveolar bone defects using DPSCs seeded on nano-hydroxyapatite/collagen/PLLA had earlier mineralization and more bone formation than achieved with the scaffold alone or even the autologous bone graft.

In a scaffold-free trial, Yamada et al[49] tried to test the osseointegration around the implant during the healing period using DPSCs. Human DPSCs were obtained from extracted permanent teeth. Adult hybrid dogs with a mean age of 2 years were operated on under general anesthesia. In the mandible region, the first molar and the second and third premolars were extracted, and the healing period was 2 mo. Bone defects were prepared on both sides of the mandible using a trephine bur with a diameter of 10 mm. The defects were implanted with DPSCs or BMSCs (1 × 107 cell/mL) plus PRP while the defect-only represented the control group. After 8 wk, an HA-coated osseointegrated dental implant was inserted into the bone regeneration areas and was assessed histologically. The dogs were sacrificed 16 wk after insertion of the dental implant. A histological analysis was performed to obtain a general description of the tissue surrounding the implants. Cavities filled with DPSCs/PRP or BMSCs/PRP were found to show new bone formation at 8 wk with a tubular pattern along with abundant vascularization. This pattern reflected normal bone macrostructure with well-differentiated marrow cavity and cortices, while the cavities in the control group were invaded by vascular and fibrous tissues. Bone-implant contact revealed significant increase in the group treated with DPSCs/PRP or BMSCs/PRP in comparison to controls.

(2) Cell sheet transplantation technique of DPSCs. In a scaffold-free trial, Fujii et al[51] evaluated bone regeneration by hDPSCs using a helioxanthin derivative and cell-sheet technology. DPSCs were cultured on temperature-responsive dishes after treatment with osteogenic medium for 14 d then the sheets were folded to fit the 3.5-mm calvarial defects of mice. The skin and subcutaneous layer were then closed by 6-0 nylon sutures. Eight weeks after surgery, calvarial defect sites were harvested from euthanized mice. Micro-CT images showed that the DPSC sheets were able to induce bone formation without requiring scaffold or growth factors. Cell sheets are flexible and simple to transplant, so this technology may replace conventional bone graft methods in the future.

Autologous hDPSCs were the source for a RCT[42] with 3 mo follow-up case series. The strategy of using DPSCs was dependent on scaffold-based only. Patients diagnosed with bilateral bone resorption following impaction surgery of impacted third molars are presented (Table 4).

DPSCs for cell and scaffold-based strategy: D’Aquino et al[54] utilized DPSCs and a collagen sponge scaffold for oro-maxillo-facial bone tissue repair in patients requiring extraction of their third molars. The patients suffered from bilateral alveolar bone reabsorption distal to the second molar following impaction of the third molar on the cortical alveolar lamina, producing a defect without walls, of 1.5 cm in height. Extraction of the third molar in this clinical condition does not permit spontaneous bone repair and ultimately leads to loss of the adjacent second molar as well. For DPC isolation and expansion, maxillary third molars were extracted. The cells were then seeded onto a collagen sponge scaffold and the biocomplex obtained was used to fill in the injury site left by extraction of the mandibular third molars. At 3 mo after autologous DPSCs grafting, the patients alveolar bone had optimal vertical repair and complete restoration of periodontal tissue back to the second molars, as assessed by clinical probing and X-rays.

DPSCs have emerged as a promising tool with a great potential for dental and oral tissue regeneration or engineering. However, many issues and challenges still need to be addressed before these cells can be employed in clinical practice. The full control of differentiation of DPSCs to specific fates is still an important issue, and although DPSCs derivation to certain connective tissue-lineage cells appears to be relatively simple, their differentiation into nerve-tissue lineages still poses important unanswered questions. Moreover, the development of the cell recombination technology required to create next-generation bioengineered replacement organs will necessitate extensive research for the coming years. In this case, DPSCs may be an ideal choice to be used in experimental models of tissue-engineered reconstruction of organs of the oral cavity, and the paradigmatic cases of the tooth and the SG may constitute the leading edge of a massive research effort on next generation organ replacement therapies[2].

| 1. | Wang Y, Preston B, Guan G. Tooth bioengineering leads the next generation of dentistry. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2012;22:406-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Aurrekoetxea M, Garcia-Gallastegui P, Irastorza I, Luzuriaga J, Uribe-Etxebarria V, Unda F, Ibarretxe G. Dental pulp stem cells as a multifaceted tool for bioengineering and the regeneration of craniomaxillofacial tissues. Front Physiol. 2015;6:289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sultan N, Amin LE, Zaher AR, Grawish ME, Scheven BA. Neurotrophic effects of dental pulp stem cells on trigeminal neuronal cells. Sci Rep. 2020;10:19694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Parisay I, Ghoddusi J, Forghani M. A review on vital pulp therapy in primary teeth. Iran Endod J. 2015;10:6-15. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Opal S, Garg S, Dhindsa A, Taluja T. Minimally invasive clinical approach in indirect pulp therapy and healing of deep carious lesions. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2014;38:185-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Song M, Yu B, Kim S, Hayashi M, Smith C, Sohn S, Kim E, Lim J, Stevenson RG, Kim RH. Clinical and Molecular Perspectives of Reparative Dentin Formation: Lessons Learned from Pulp-Capping Materials and the Emerging Roles of Calcium. Dent Clin North Am. 2017;61:93-110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kuang R, Zhang Z, Jin X, Hu J, Shi S, Ni L, Ma PX. Nanofibrous spongy microspheres for the delivery of hypoxia-primed human dental pulp stem cells to regenerate vascularized dental pulp. Acta Biomater. 2016;33:225-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gonçalves LF, Fernandes AP, Cosme-Silva L, Colombo FA, Martins NS, Oliveira TM, Araujo TH, Sakai VT. Effect of EDTA on TGF-β1 released from the dentin matrix and its influence on dental pulp stem cell migration. Braz Oral Res. 2016;30:e131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Komabayashi T, Zhu Q, Eberhart R, Imai Y. Current status of direct pulp-capping materials for permanent teeth. Dent Mater J. 2016;35:1-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Marrelli M, Codispoti B, Shelton RM, Scheven BA, Cooper PR, Tatullo M, Paduano F. Dental Pulp Stem Cell Mechanoresponsiveness: Effects of Mechanical Stimuli on Dental Pulp Stem Cell Behavior. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wang J, Ma H, Jin X, Hu J, Liu X, Ni L, Ma PX. The effect of scaffold architecture on odontogenic differentiation of human dental pulp stem cells. Biomaterials. 2011;32:7822-7830. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Pan S, Dangaria S, Gopinathan G, Yan X, Lu X, Kolokythas A, Niu Y, Luan X. SCF promotes dental pulp progenitor migration, neovascularization, and collagen remodeling - potential applications as a homing factor in dental pulp regeneration. Stem Cell Rev Rep. 2013;9:655-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Horibe H, Murakami M, Iohara K, Hayashi Y, Takeuchi N, Takei Y, Kurita K, Nakashima M. Isolation of a stable subpopulation of mobilized dental pulp stem cells (MDPSCs) with high proliferation, migration, and regeneration potential is independent of age. PLoS One. 2014;9:e98553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chaudhary SC, Kuzynski M, Bottini M, Beniash E, Dokland T, Mobley CG, Yadav MC, Poliard A, Kellermann O, Millán JL, Napierala D. Phosphate induces formation of matrix vesicles during odontoblast-initiated mineralization in vitro. Matrix Biol. 2016;52-54:284-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zhang M, Jiang F, Zhang X, Wang S, Jin Y, Zhang W, Jiang X. The Effects of Platelet-Derived Growth Factor-BB on Human Dental Pulp Stem Cells Mediated Dentin-Pulp Complex Regeneration. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2017;6:2126-2134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hjørting-Hansen E. Bone grafting to the jaws with special reference to reconstructive preprosthetic surgery. A historical review. Mund Kiefer Gesichtschir. 2002;6:6-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Miron RJ, Sculean A, Cochran DL, Froum S, Zucchelli G, Nemcovsky C, Donos N, Lyngstadaas SP, Deschner J, Dard M, Stavropoulos A, Zhang Y, Trombelli L, Kasaj A, Shirakata Y, Cortellini P, Tonetti M, Rasperini G, Jepsen S, Bosshardt DD. Twenty years of enamel matrix derivative: the past, the present and the future. J Clin Periodontol. 2016;43:668-683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Needleman IG, Worthington HV, Giedrys-Leeper E, Tucker RJ. Guided tissue regeneration for periodontal infra-bony defects. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;CD001724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Andrei M, Dinischiotu A, Didilescu AC, Ionita D, Demetrescu I. Periodontal materials and cell biology for guided tissue and bone regeneration. Ann Anat. 2018;216:164-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Park JY, Jeon SH, Choung PH. Efficacy of periodontal stem cell transplantation in the treatment of advanced periodontitis. Cell Transplant. 2011;20:271-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 145] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Owaki T, Shimizu T, Yamato M, Okano T. Cell sheet engineering for regenerative medicine: current challenges and strategies. Biotechnol J. 2014;9:904-914. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 144] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wei F, Qu C, Song T, Ding G, Fan Z, Liu D, Liu Y, Zhang C, Shi S, Wang S. Vitamin C treatment promotes mesenchymal stem cell sheet formation and tissue regeneration by elevating telomerase activity. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227:3216-3224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Li D, Feng Y, Tang H, Huang L, Tong Z, Hu C, Chen X, Tan J. A Simplified and Effective Method for Generation of Experimental Murine Periodontitis Model. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020;8:444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Oz HS, Puleo DA. Animal models for periodontal disease. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:754857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 188] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Khorsand A, Eslaminejad MB, Arabsolghar M, Paknejad M, Ghaedi B, Rokn AR, Moslemi N, Nazarian H, Jahangir S. Autologous dental pulp stem cells in regeneration of defect created in canine periodontal tissue. J Oral Implantol. 2013;39:433-443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ma L, Hu J, Cao Y, Xie Y, Wang H, Fan Z, Zhang C, Wang J, Wu CT, Wang S. Maintained Properties of Aged Dental Pulp Stem Cells for Superior Periodontal Tissue Regeneration. Aging Dis. 2019;10:793-806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Cao Y, Liu Z, Xie Y, Hu J, Wang H, Fan Z, Zhang C, Wang J, Wu CT, Wang S. Adenovirus-mediated transfer of hepatocyte growth factor gene to human dental pulp stem cells under good manufacturing practice improves their potential for periodontal regeneration in swine. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015;6:249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hu J, Cao Y, Xie Y, Wang H, Fan Z, Wang J, Zhang C, Wu CT, Wang S. Periodontal regeneration in swine after cell injection and cell sheet transplantation of human dental pulp stem cells following good manufacturing practice. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2016;7:130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Li Y, Nan X, Zhong TY, Li T, Li A. Treatment of Periodontal Bone Defects with Stem Cells from Inflammatory Dental Pulp Tissues in Miniature Swine. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2019;16:191-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lin CY, Tsai MS, Kuo PJ, Chin YT, Weng IT, Wu Y, Huang HM, Hsiung CN, Lin HY, Lee SY. 2,3,5,4'-Tetrahydroxystilbene-2-O-β-d-glucoside promotes the effects of dental pulp stem cells on rebuilding periodontal tissues in experimental periodontal defects. J Periodontol. 2021;92:306-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Meng H, Hu L, Zhou Y, Ge Z, Wang H, Wu CT, Jin J. A Sandwich Structure of Human Dental Pulp Stem Cell Sheet, Treated Dentin Matrix, and Matrigel for Tooth Root Regeneration. Stem Cells Dev. 2020;29:521-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Shen Z, Kuang S, Zhang Y, Yang M, Qin W, Shi X, Lin Z. Chitosan hydrogel incorporated with dental pulp stem cell-derived exosomes alleviates periodontitis in mice via a macrophage-dependent mechanism. Bioact Mater. 2020;5:1113-1126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 33.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Li Y, Zhao S, Nan X, Wei H, Shi J, Li A, Gou J. Repair of human periodontal bone defects by autologous grafting stem cells derived from inflammatory dental pulp tissues. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2016;7:141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Ferrarotti F, Romano F, Gamba MN, Quirico A, Giraudi M, Audagna M, Aimetti M. Human intrabony defect regeneration with micrografts containing dental pulp stem cells: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2018;45:841-850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 35. | Aimetti M, Ferrarotti F, Gamba MN, Giraudi M, Romano F. Regenerative Treatment of Periodontal Intrabony Defects Using Autologous Dental Pulp Stem Cells: A 1-Year Follow-Up Case Series. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2018;38:51-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 36. | Hernández-Monjaraz B, Santiago-Osorio E, Ledesma-Martínez E, Aguiñiga-Sánchez I, Sosa-Hernández NA, Mendoza-Núñez VM. Dental Pulp Mesenchymal Stem Cells as a Treatment for Periodontal Disease in Older Adults. Stem Cells Int. 2020;2020:8890873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Holmberg KV, Hoffman MP. Anatomy, biogenesis and regeneration of salivary glands. Monogr Oral Sci. 2014;24:1-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Vissink A, Mitchell JB, Baum BJ, Limesand KH, Jensen SB, Fox PC, Elting LS, Langendijk JA, Coppes RP, Reyland ME. Clinical management of salivary gland hypofunction and xerostomia in head-and-neck cancer patients: successes and barriers. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;78:983-991. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 234] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Lim JY, Ra JC, Shin IS, Jang YH, An HY, Choi JS, Kim WC, Kim YM. Systemic transplantation of human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells for the regeneration of irradiation-induced salivary gland damage. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Lombaert I, Movahednia MM, Adine C, Ferreira JN. Concise Review: Salivary Gland Regeneration: Therapeutic Approaches from Stem Cells to Tissue Organoids. Stem Cells. 2017;35:97-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Kim JY, An CH, Kim JY, Jung JK. Experimental Animal Model Systems for Understanding Salivary Secretory Disorders. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Janebodin K, Reyes M. Neural crest-derived dental pulp stem cells function as ectomesenchyme to support salivary gland tissue formation. Dentistry. 2012;S13:001. |

| 43. | Yamamura Y, Yamada H, Sakurai T, Ide F, Inoue H, Muramatsu T, Mishima K, Hamada Y, Saito I. Treatment of salivary gland hypofunction by transplantation with dental pulp cells. Arch Oral Biol. 2013;58:935-942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Narmada IB, Laksono V, Nugraha AP, Ernawati DS, Winias S, Prahasanti C, Dinaryanti A, Susilowati H, Hendrianto E, Ihsan IS, Rantam FA. Regeneration of Salivary Gland Defects of Diabetic Wistar Rats Post Human Dental Pulp Stem Cells Intraglandular Transplantation on Acinar Cell Vacuolization and Interleukin-10 Serum Level. Pesqui Bras Odontopediatria Clín Integr. 2019;19:e5002. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Takeuchi H, Takahashi H, Tanaka A. Effects of human dental pulp stem cell-derived conditioned medium on atrophied submandibular gland after the release from ligation of the main excretory duct in mice. J Hard Tissue Biol. 2020;29:183-192. |

| 46. | Lee JE, Jin SH, Ko Y, Park JB. Evaluation of anatomical considerations in the posterior maxillae for sinus augmentation. World J Clin Cases. 2014;2:683-688. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 47. | Langenbach F, Handschel J. Effects of dexamethasone, ascorbic acid and β-glycerophosphate on the osteogenic differentiation of stem cells in vitro. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2013;4:117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 364] [Cited by in RCA: 474] [Article Influence: 39.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Boonyagul S, Banlunara W, Sangvanich P, Thunyakitpisal P. Effect of acemannan, an extracted polysaccharide from Aloe vera, on BMSCs proliferation, differentiation, extracellular matrix synthesis, mineralization, and bone formation in a tooth extraction model. Odontology. 2014;102:310-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Yamada Y, Nakamura S, Ito K, Sugito T, Yoshimi R, Nagasaka T, Ueda M. A feasibility of useful cell-based therapy by bone regeneration with deciduous tooth stem cells, dental pulp stem cells, or bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells for clinical study using tissue engineering technology. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16:1891-1900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Liu HC, E LL, Wang DS, Su F, Wu X, Shi ZP, Lv Y, Wang JZ. Reconstruction of alveolar bone defects using bone morphogenetic protein 2 mediated rabbit dental pulp stem cells seeded on nano-hydroxyapatite/collagen/poly(L-lactide). Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:2417-2433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Fujii Y, Kawase-Koga Y, Hojo H, Yano F, Sato M, Chung UI, Ohba S, Chikazu D. Bone regeneration by human dental pulp stem cells using a helioxanthin derivative and cell-sheet technology. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9:24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 52. | Mohammed EE, El-Zawahry M, Farrag AH, Abdel Aziz NN, Abou-Shahba N, Mahmoud M, El-Mohandes WA, El-Farmawy MA, Abdel Aleem AK. Osteogenic potential of human dental pulp-derived mesenchymal stem cells in bone regeneration of rabbit. J Arab Soc Med Res. 2019;14:102-112. |

| 53. | Chamieh F, Collignon AM, Coyac BR, Lesieur J, Ribes S, Sadoine J, Llorens A, Nicoletti A, Letourneur D, Colombier ML, Nazhat SN, Bouchard P, Chaussain C, Rochefort GY. Accelerated craniofacial bone regeneration through dense collagen gel scaffolds seeded with dental pulp stem cells. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38814. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 54. | d'Aquino R, De Rosa A, Lanza V, Tirino V, Laino L, Graziano A, Desiderio V, Laino G, Papaccio G. Human mandible bone defect repair by the grafting of dental pulp stem/progenitor cells and collagen sponge biocomplexes. Eur Cell Mater. 2009;18:75-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 303] [Cited by in RCA: 310] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Dentistry, oral surgery and medicine

Country/Territory of origin: Egypt

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: Kannan T, Tsutsui TW S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Li JH