Published online Sep 26, 2015. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v5.i3.144

Peer-review started: May 11, 2015

First decision: June 9, 2015

Revised: August 11, 2015

Accepted: September 1, 2015

Article in press: September 2, 2015

Published online: September 26, 2015

Processing time: 146 Days and 21.1 Hours

Structured training in endonasal endoscopic sinus surgery (EESS) and skull base surgery is essential considering serious potential complications. We have developed a detailed concept on training these surgical skills on the lamb’s head. This simple and extremely cheap model offers the possibility of training even more demanding and advanced procedures in human endonasal endoscopic surgery such as: frontal sinus surgery, orbital decompression, cerebrospinal fluid-leak repair followed also by the naso-septal flap, etc. Unfortunately, the sphenoid sinus surgery cannot be practiced since quadrupeds do not have this sinus. Still, despite this anatomical limitation, it seems that the lamb’s head can be very useful even for the surgeons already practicing EESS, but in a limited edition because of a lack of the experience and dexterity. Only after gaining the essential surgical skills of this demanding field it makes sense to go for the expensive trainings on the human cadaveric model.

Core tip: Structured training in endonasal endoscopic sinus surgery (EESS) and skull base surgery is essential considering serious potential complications. We have developed a detailed concept on training these surgical skills on the lamb’s head. This simple and extremely cheap model offers the possibility of training even more demanding and advanced procedures in human EESS such as: frontal sinus surgery, orbital decompression, cerebrospinal fluid-leak repair followed also by the naso-septal flap, etc. Unfortunately, the sphenoid sinus surgery cannot be practiced since quadrupeds do not have this sinus. Still, despite this morphological limitation, it seems that the lamb’s head can be very useful model.

- Citation: Skitarelić N, Mladina R. Lamb’s head: The model for novice education in endoscopic sinus surgery. World J Methodol 2015; 5(3): 144-148

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v5/i3/144.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v5.i3.144

Endonasal endoscopic sinus surgery (EESS) procedures are one of the most common surgical procedures performed in nowadays otorhinolaryngology. They are considered the gold-standard treatment for several entities regarding the paranasal sinuses and nasal cavity[1,2]. The orientation within the anatomic structures and a proper use of the surgical instruments during the procedures is challenging for the inexperienced surgeon, owing to the complexity of the intranasal anatomy and the intimate relation with noble structures, such as the brain, the carotid arteries, the eye-ball, orbit and the optic nerve itself[1-4]. Nowadays, the training of the novices in endonasal sinus and skull base surgery is conducted in the operating room, upon the real patients, under the surveillance of more experienced surgeons[1,2]. The complication rate in endonasal sinus and skull base surgery may vary from 5% to 8%[2]. The low and flat learning curve of the particular novices may increase the risk of serious complications. To prevent additional problems to both novices and their supervisors as well as to protect patients, all activities that objectively can help to over-bridge the gaps in theoretical and practical expertise should be employed. One of these activities undoubtedly is the lamb’s head dissection training according to our model.

In terms of that, a comprehensive booklet on this matter has been written by our team and published so far in Croatian, English, Italian and Russian language by Karl Storz GmbH (Germany)[5]. In collaboration with the same manufacturer we have produced also an attractive DVD on complete dissection in a “step-by-step” manner.

The first distinctive feature that arises when entering the lamb’s nose is an abundant similarity to the human nasal cavity. Lamb’s septum does not have vomer at all, thus a typical triangular lack of septum can be seen endoscopicaly in the deepest septal regions.

The inferior turbinate could be most confusing detail at the beginning since it resembles very much the middle turbinate in man. In veterinary terminology it is named concha ventralis, meaning anterior turbinate. According to the veterinary anatomical nomenclature, the term “middle turbinate” (concha nasalis media) in lamb is used to denominate a structure that is located much deeper in the lamb’s nose, and can be clearly seen only if almost all of the inferior turbinate has been removed. The lamb’s inferior turbinate has two main portions: the superior one, named pars dorsalis and the inferior one, named pars ventralis.

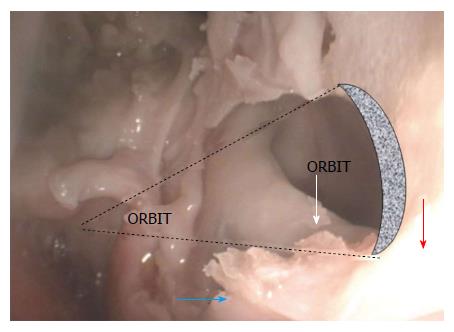

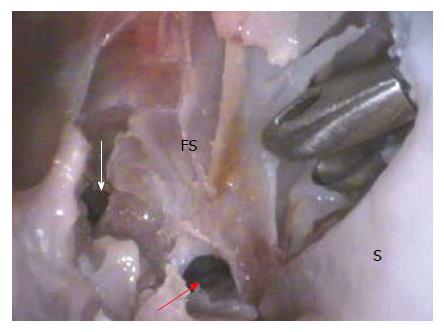

The nasal septum is straight as in all other quadrupeds. The maxillary sinus consist of two “sub-sinuses” since a perpendicular crest, arising from the bottom of this sinus, divides it in a laterally positioned, spacious cavity, so called maxillary sinus proper, and medially positioned, poky sinus named palatinal sinus. The superior, free edge of the crest that divides maxillary cavity into two sinuses is characterized by the course of the infraorbital nerve within its bone. The formation of the middle antrostomy is easy, simple, instructive and motivating for the next steps of the dissection. Posterior wall of both palatal sinus and maxillary sinus proper is at the same time the anterior orbital wall thus making an endoscopic approach to the orbital decompression relatively simple. The frontal sinus consists of queue of chambers positioned semicircular in the frontal bone thus forming a structure that resembles very much a crown. Frontal sinus is also relatively easy to approach since the surgeon has a reliable signpost: the superior turbinate gradually, as getting deeper and deeper with the instruments and endoscope, gets a tube-like form. At the bottom of this tube the surgeon finds himself in the first, most anteriorly positioned, so called supraorbital frontal sinus cell. The sphenoid sinus surgery can’t be practiced in lamb’s head model since quadrupeds, because of the lack of the skull base angulation (Huxley’s angle) do not have this sinus.

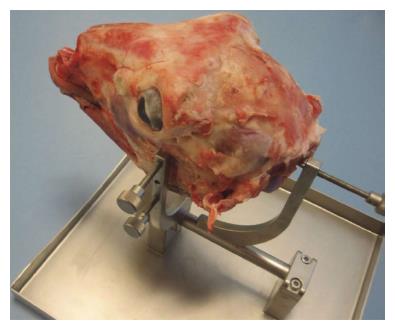

The lamb heads are purchased fresh at the butcher’s shop (approximate price is about two US$) and the muzzle is always cut off (cartilaginous part) as to make the entrance to the nasal cavities much easier and practical. After that, the heads are washed under the tap water and then put into a tree-liters bowl of water containing three tablespoons of alcoholic vinegar. After 24 h of soaking the heads are usually left to drain in the sink for 30 min, than wiped with a clean cloth and finally frozen at -18 °C until the moment they will be used for the dissection. On the day of dissection the heads are unfrozen, washed and wiped. Heads prepared in this manner are far more easy to use, without an excess of grease and fluids. For the dissection purposes the heads are mounted in a special Lamb’s Head Holder (Karl Storz GmbH) (Figure 1).

The dissection usually consists of ten classical steps. Step 1 concerns to the very simple task: removal of the inferior turbinate; Step 2 concerns to the clear presentation of the adenoids and Eustachian tube openings bilaterally, while Step 3 regards to the clear presentation of the middle turbinate, uncinectomy and middle antrostomy followed by as clear as possible presentation of the perpendicular crest within its cavity that divides it into the maxillary sinus proper (lateral compartment), and palatine sinus (medial compartment) (Figure 2). The superior edge of this crest contains the infraorbital nerve canal; Step 4 means the identification of the posterior wall of palatine sinus which is, at the same time, the medial half of the anterior orbital wall, followed by alignment with its lateral half, i.e., posterior wall of the maxillary sinus proper; Step 5 is performed in sense of the endonasal endoscopic orbital decompression; Step 6 belongs to the ethmoidectomy, whereas Step 7 mean the formation of the artificial skull base defect, presentation of dura, followed by insertion of the artificial patch in the underlay manner; Step 8 means an elevation and adequate positioning of the nasoseptal flap to be used to cover the closed skull base defect in an overlay manner. The next, 9th Step, belongs to the removal of the tube-like formation, so called dorsal turbinate (plica recta), positioned at the anterior part of the roof of the nasal cavity, which transforms gradually, getting more posterior, into dorsal turbinate and leads directly to the opening of the supraorbital frontal sinus chamber first. Once opened, this cell leads the surgeon to the more anteriorly and medially positioned frontal sinus cells. Finally, the Step 10 concerns to the removal of the most superior part of the nasal septum as to make the bottom of the frontal sinus visible from both sides and thus bilaterally approachable. Afterwards, the same procedure as described in Step 9 is repeated on the opposite side in order to open the contra lateral frontal sinus chambers. Finally one has to drill out the bony bottom of the frontal sinus thus connecting the previously opened cells in one, large cavity - Draf III procedure (Figure 3).

Safe endonasal endoscopic sinus and skull base surgery requires a good and reliable knowledge on surgical anatomy and, at the same time, the safe usage of the endoscopes and instruments. Many institutions around the world insist on trainings performed upon the human cadaveric model before the surgeon undertakes his/her first surgery on a real patient[6-8]. Training courses and workshops in EESS provide a well structured supervised approach to endonasal anatomy and technical training. Unfortunately, these trainings can be achieved once or, at the most, twice during the particular novice’s education because of very high registration fees for the courses. Even more, they do not offer the calm that the novice, confused and scared from all sides, can’t get. Such courses, regardless of the fact that almost always are perfectly organized, have the disadvantage, not only of being such expensive, but also of being dependent on the strict medico-legal regulations regarding the question of collecting, storage and disposal of the human cadaveric heads which, nowadays, represents a rapidly growing problem in the increasing number of countries all over. Artificial models of human heads were also designed and available for training[9] but are highly priced. Furthermore, endoscopic sinus surgery simulators have also been introduced as teaching tools for EESS[1,10,11].

However, in our opinion, the initial goal for the novices in the field of endoscopic endonasal sinus surgery is to gain the surgical skills and to become familiar with the complexity of simultaneous bimanual work in operating field, distant from that what they actually see on the monitor during their work. So, the trainees should be firstly trained on the animal models as to become more skilled with the endoscopes of various angles, orientation and understanding the surgical space and field, and to get skilled in the use of the instruments. The study of human anatomy on the cadaveric dissections should be only the second step in any case. In this way the learning curve for EESS gets more attractive thus giving the novices, i.e., trainees more confidence in operating area and better understanding of anatomical details they are about to dissect. Animal model of a comparable sino-nasal appearance to human seems to be the logical choice for the initial training of surgical skills.

Paying a great respect to Gardiner’s introduction of a sheep model for training in EESS[12], we have developed a detailed study for training on the lamb’s head, combining radiology findings, frozen three-axis sections and a meticulous research on lamb’s sino-nasal surgical anatomy as to facilitate the first steps in EESS for all those who approach this field[5].

This was the result of long lasting attempts to find a low-cost and suitable animal model that will fit two most important demands: (1) high degree of the anatomical similarity to human sino-nasal anatomy; and (2) the appropriate dimensions of the sino-nasal unit that will allow the easy use of the standard endoscopic sinus surgery instruments otherwise used in human medicine. We have tried with dogs, pigs, sheep and goats, but, at the end, we found everything we needed with the lamb’s head[13]. Some years ago we also developed a special head holder for the lamb’s head, produced by Karl Storz, Germany. The lamb’s head as a simple and extremely cheap model offers the possibility of training even more demanding and advanced procedures in human endonasal endoscopic surgery such as endoscopic endonasal orbital decompression, Draf III procedure or cerebrospinal fluid leak repair, including the naso-septal flap[14]. Dacryocystorhinostomy can’t be performed since the lamb does not have the lacrimal sac at all[4]. The sphenoid sinus surgery can’t be practiced either, since quadrupeds do not have this sinus because of the natural lack of the skull base angulation. Still, despite these two morphological limitations, it seems that the lamb’s head model can be very useful also for the surgeons that want to amend their technique and take it to a higher level. In terms of that, it was mandatory to have also the navigational system for the lamb’s head and it was built by Karl Storz GmbH as well.

Regarding maxillary sinus, it’s amazingly easy to perform middle antrostomy Frontal sinus surgery resembling Draf 1, 2 and 3 procedures can be trained with the ease and calm as well.

In our opinion the lamb’s head is an effective, extremely cheap and user-friendly animal model for learning and training the endonasal endoscopic sinus and skull base surgery techniques.

We have developed a practical and detailed program for the training of surgical techniques in EESS on the lamb’s head, combining radiology findings, frozen three-axis sections and a meticulous research on lamb’s sinonasal surgical anatomy. Lamb’s head proved to be an excellent model with comparable anatomy to that in humans and thus very appropriate to practice the usual EESS techniques with ease using the standard EESS instruments.

The authors would like to thank Karl Storz GmbH for their generous help and support in development of an animal model for training in functional endoscopic sinus surgery.

| 1. | Arora H, Uribe J, Ralph W, Zeltsan M, Cuellar H, Gallagher A, Fried MP. Assessment of construct validity of the endoscopic sinus surgery simulator. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;131:217-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Hosemann W, Draf C. Danger points, complications and medico-legal aspects in endoscopic sinus surgery. GMS Curr Top Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;12:Doc06. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Touska P, Awad Z, Tolley NS. Suitability of the ovine model for simulation training in rhinology. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:1598-1601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mladina R, Vuković K, Štern Padovan R, Skitarelić N. An animal model for endoscopic endonasal surgery and dacryocystorhinostomy training: uses and limitations of the lamb’s head. J Laryngol Otol. 2011;125:696-700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mladina R. Endoscopic Surgical Anatomy of the Lamb’s Head. Storz Endo PressTM, Tuttlingen, Germany. 2011;. |

| 6. | Kinsella JB, Calhoun KH, Bradfield JJ, Hokanson JA, Bailey BJ. Complications of endoscopic sinus surgery in a residency training program. Laryngoscope. 1995;105:1029-1032. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Montague ML, Kishore A, McGarry GW. Audit-derived guidelines for training in endoscopic sinonasal surgery (ESS)--protecting patients during the learning curve. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2003;28:411-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zuckerman JD, Wise SK, Rogers GA, Senior BA, Schlosser RJ, DelGaudio JM. The utility of cadaver dissection in endoscopic sinus surgery training courses. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2009;23:218-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Briner HR, Simmen D, Jones N, Manestar D, Manestar M, Lang A, Groscurth P. Evaluation of an anatomic model of the paranasal sinuses for endonasal surgical training. Rhinology. 2007;45:20-23. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Fried MP, Sadoughi B, Gibber MJ, Jacobs JB, Lebowitz RA, Ross DA, Bent JP, Parikh SR, Sasaki CT, Schaefer SD. From virtual reality to the operating room: the endoscopic sinus surgery simulator experiment. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2010;142:202-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Nogueira JF, Stamm AC, Lyra M, Balieiro FO, Leão FS. Building a real endoscopic sinus and skull-base surgery simulator. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;139:727-728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gardiner Q, Oluwole M, Tan L, White PS. An animal model for training in endoscopic nasal and sinus surgery. J Laryngol Otol. 1996;110:425-428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mladina R, Skitarelić N. Training model for endoscopic sinus surgery. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2013;27:251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Mladina R, Castelnuovo P, Locatelli D, Đurić Vuković K, Skitarelić N. Training cerebrospinal fluid leak repair with nasoseptal flap on the lamb’s head. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2013;75:32-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P- Reviewer: Coskun A, Noussios G, Unal M S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Jiao XK