Published online Mar 20, 2026. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v16.i1.111566

Revised: August 6, 2025

Accepted: August 28, 2025

Published online: March 20, 2026

Processing time: 222 Days and 16.2 Hours

In-stent restenosis (ISR) is a persistent challenge after percutaneous coronary intervention, with drug-coated balloons such as sirolimus-coated balloons (SCBs) and paclitaxel-coated balloons (PCBs) being key treatment options. However, data comparing their efficacy and safety are limited.

To evaluate the comparative efficacy and safety of SCBs vs PCBs in patients with coronary ISR.

A systematic search of PubMed, EMBASE, and ScienceDirect was conducted from inception to May 2025, following Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. Eligible studies were randomized controlled trials and observational studies comparing SCBs and PCBs in adults with coronary ISR, reporting outcomes like target lesion revascularization (TLR), major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), stent thrombosis, all-cause mortality, cardiac mortality, and myocardial infarction. Risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using a random-effects model. Heterogeneity was assessed with the I2 statistic, and study quality was evaluated using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 tool and Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Four studies (three randomized controlled trials and one observational study) were analyzed. No significant differences were found between SCBs and PCBs for TLR (RR 1.22, 95%CI: 0.72-2.06, P = 0.75, I2 = 0%), MACE (RR 1.15, 95%CI: 0.70-1.90, P = 0.80, I2 = 0%), stent thrombosis (RR 1.01, 95%CI: 0.57-1.78, P = 0.61, I2 = 0%), all-cause mortality (RR 0.67, 95%CI: 0.11-4.06, P = 0.69, I2 = 0%), cardiac mortality (RR 1.28, 95%CI: 0.16-10.28, P = 0.77, I2 = 0%), or myocardial infarction (RR 0.99, 95%CI: 0.10-9.44, P = 0.35, I2 = 0%). Studies had low to moderate risk of bias, with consistent treatment effects.

SCBs and PCBs show similar efficacy and safety for coronary ISR, allowing flexible use based on availability and patient needs. Future studies should explore long-term outcomes and high-risk groups to optimize ISR mana

Core Tip: This meta-analysis systematically compares sirolimus-coated balloons (SCBs) and paclitaxel-coated balloons (PCBs) for treating coronary in-stent restenosis (ISR). Synthesizing data from randomized controlled trials and observational studies, the findings demonstrate no significant differences between SCBs and PCBs in efficacy or safety outcomes, including target lesion revascularization and major adverse cardiovascular events. These results support flexible clinical use of either DCB type for ISR, while highlighting the need for further research into long-term outcomes and high-risk patient subgroups.

- Citation: Mandal D, Pulickal TV, Ahlawat D, Haqbeen W, Kashif I, Alamy H, Prattipati P, Jaladi P, Kabiaru P, Avula A, Kshetri S, Raza I, Shamieh S, Chhetri R. Sirolimus vs paclitaxel-coated balloons in in-stent coronary restenosis: A meta-analysis. World J Methodol 2026; 16(1): 111566

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v16/i1/111566.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v16.i1.111566

In-stent restenosis (ISR) is the recurrence of luminal narrowing at the site of a previously implanted coronary stent, typically following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Assessed via coronary angiography, ISR occurs within the stent or within 5 mm of its margins and is primarily driven by neointimal hyperplasia[1,2]. Despite advancements in stent technology, ISR remains a clinical challenge, particularly in high-risk patients with diabetes, small vessels, or long lesions[3]. It often leads to recurrent symptoms, including acute coronary syndromes, necessitating target lesion revascularization (TLR), which increases procedural risks and impairs quality of life[4,5].

Historically, plain old balloon angioplasty (POBA) was the initial salvage strategy for ISR but was limited by high rates of luminal loss, elastic recoil, and neointimal hyperplasia[6]. These shortcomings prompted the development of solutions combining mechanical support with pharmacologic inhibition of restenosis. Drug-coated balloons (DCBs), which deliver antiproliferative drugs directly to the vessel wall without additional stent implantation, have become a preferred option for ISR. DCBs address neointimal hyperplasia while avoiding the limitations of POBA, such as elastic recoil and high restenosis rates[7]. The two main DCB types are paclitaxel-coated balloons (PCBs) and sirolimus-coated balloons (SCBs). PCBs, leveraging paclitaxel’s cytotoxic suppression of neointimal proliferation, have been extensively studied. Trials like PACCOCATH-ISR and PEPCAD II demonstrated that PCBs reduce late lumen loss, binary restenosis, and TLR compared to conventional angioplasty or repeat stenting[8,9]. However, concerns about paclitaxel’s long-term safety, including a potential link to increased mortality in peripheral artery disease, have raised questions about their use[10].

SCBs, utilizing sirolimus—a cytostatic mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor with a wider therapeutic index—offer a potential alternative[11]. Advances in carrier technology have improved sirolimus’ drug transfer efficiency, achieving outcomes comparable to PCBs in studies like the SIRPAC trial[12]. While PCBs are well-validated, SCBs are increasingly considered for their potential safety advantages, particularly in high-risk patients[13]. However, inconsistent findings and limited long-term data create uncertainty about their comparative efficacy and safety. This meta-analysis aims to quantitatively assess the safety and efficacy of SCBs vs PCBs in coronary ISR, providing evidence-based guidance for device selection and identifying areas for further research.

This systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines[14,15]. The protocol is registered on PROSPERO CRD420251057162.

A comprehensive electronic search of PubMed, EMBASE, and ScienceDirect was conducted from their inception to May 2025. The search strategy combined Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms and free-text keywords, including “in-stent restenosis”, “coronary restenosis”, “drug-coated balloon”, “drug-eluting balloon”, “sirolimus-coated balloon”, “paclitaxel-coated balloon”, “sirolimus”, “paclitaxel”, and “percutaneous coronary intervention”. These terms were tailored to each database to identify studies based on predefined population, intervention, comparison, and outcome criteria. Manual searches of bibliographies and grey literature, including conference proceedings, abstracts, and preprints, were performed to ensure comprehensive data collection. Filters included English language, human studies, and original research.

Eligible studies were original comparative studies (randomized controlled trials or observational studies) enrolling adults with coronary ISR; studies of de novo lesions were excluded. Studies had to evaluate SCBs with PCBs as the control and report at least one clinical endpoint, such as major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), myocardial infarction, TLR, or death. Studies comparing sirolimus-eluting stents with paclitaxel-eluting stents, case reports, narrative reviews, editorials, conference abstracts without full data, and preclinical or animal experiments were excluded.

Two independent reviewers (Mandal D and Pulickal TV) screened titles and abstracts to exclude irrelevant studies. Full-text articles of potentially eligible studies were retrieved and systematically assessed for inclusion. Disagreements were resolved through discussion, with a third reviewer (Alamy H) if necessary.

Data were extracted using a pre-piloted Google Spreadsheet capturing study characteristics, participant demographics, and clinical outcomes. Extracted data included baseline characteristics (sample size, age, gender, prevalence of diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, smoking), procedural characteristics [DCB length, diameter, dissection rate, balloon pressure, inflation time, pre-PCI minimal lumen diameter (MLD) for lesion and segment], and clinical outcomes (TLR, stent thrombosis, all-cause mortality, MACE, cardiac mortality, myocardial infarction). Two reviewers (Kashif I and Alamy H) independently extracted data, resolving discrepancies through consensus. Corresponding authors were contacted for missing data, with a one-week response period. Two additional reviewers cross-verified extracted data against original sources to ensure accuracy.

The risk of bias for randomized controlled trials was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 (RoB 2.0) tool, evaluating five domains: Randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, outcome measurement, and selection of reported results[16]. Each domain was judged as low, some concerns, or high risk of bias, with an overall risk determined per study. The single non-randomized observational study was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS), evaluating selection, comparability, and outcome domains, with a maximum score of 9 indicating high quality[17].

Statistical analyses were conducted using Review Manager 5.4 (Cochrane Collaboration). Risk ratios (RRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were the primary effect measure due to their interpretability. A random-effects model was applied, assuming a single underlying true effect size across studies. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic and a P value < 0.05 for the summary effect was considered statistically significant. For each outcome, a forest plot was constructed to visually analyze the data and funnel plots were generated to check the publication bias. Following the statistical analysis, the quality of evidence for each outcome was evaluated using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach, assessing domains such as risk of bias, inconsistency, imprecision, indirectness, and effect size to determine the certainty of evidence.

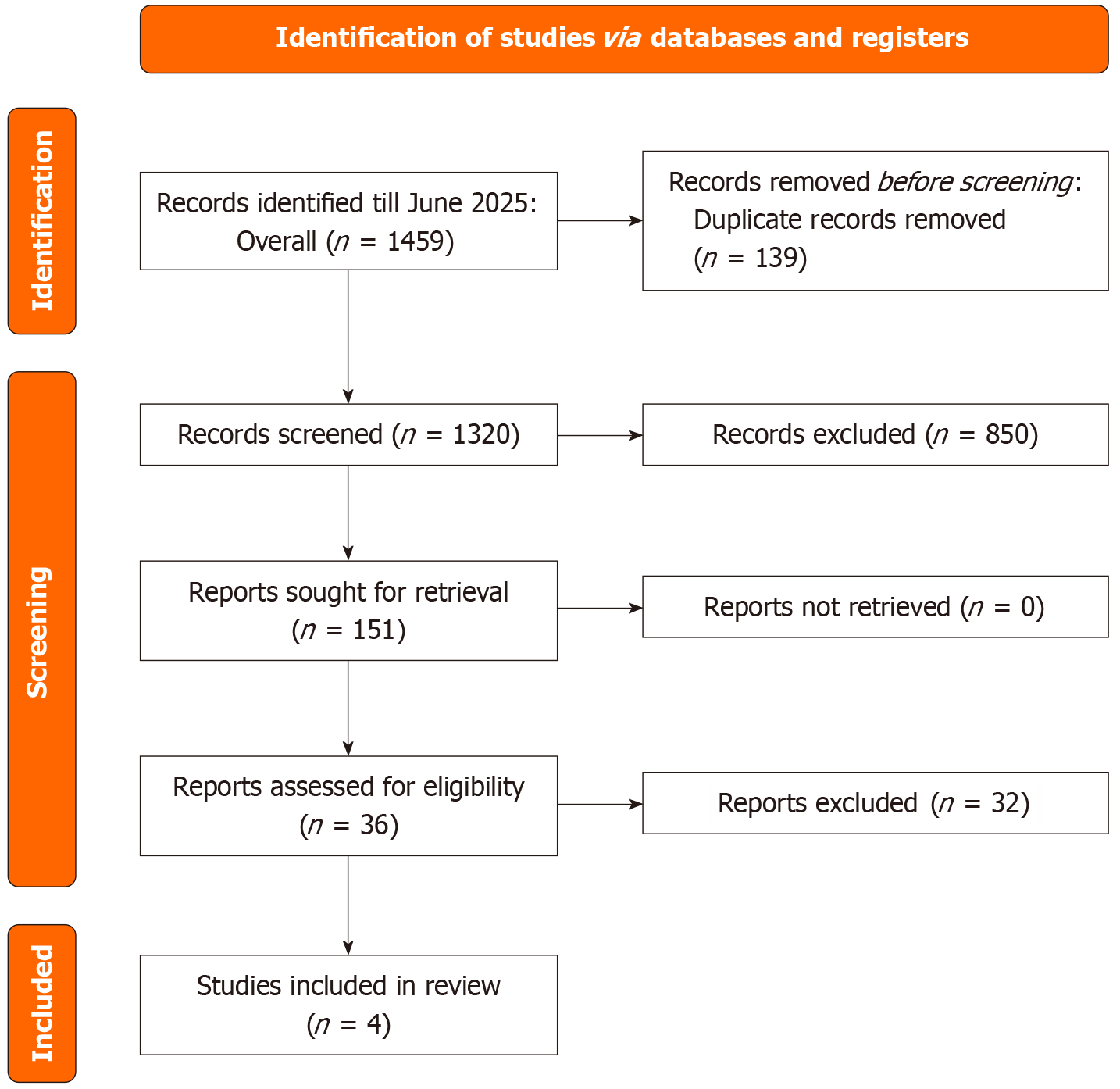

The PRISMA statement flowchart (Figure 1) outlines the literature screening process and study selection. The initial search yielded 1692 articles, from which 36 full-text articles were retrieved for assessment. Ultimately, 4 studies[7,18-20] met the eligibility criteria and were included in both the qualitative and quantitative meta-analyses.

Four studies provided baseline characteristics for patients treated with SCBs or PCBs for coronary in-stent restenosis, with sample sizes ranging from 25 to 130 per group. Mean ages were comparable between SCB and PCB groups (58.6-67.2 years for SCBs; 63.0-63.7 years for PCBs). Male predominance was observed (73.1%-88% for SCBs; 75.8%-96.9% for PCBs). Prevalence of diabetes mellitus varied (33.8%-73.6% for SCBs; 41.4%-81.3% for PCBs), with generally similar rates of hypertension (66.9%-98% for SCBs; 70.3%-94% for PCBs) and hyperlipidemia (17.7%-92% for SCBs; 14.1%-84% for PCBs, where reported). Smoking prevalence was reported in two studies, ranging from 16%-22% for SCBs and 8%-12% for PCBs. Overall, baseline characteristics were broadly comparable between SCB and PCB groups, with minor variations in diabetes and smoking rates (Table 1).

| Ref. | Study design | Country | Follow up period | Sample size | Age, year; mean ± SD | Male (%) | Diabetes mellitus (%) | Hypertension (%) | Hyperlipidemia (%) | Smoking (%) | |||||||

| SCB | PCB | SCB | PCB | SCB | PCB | SCB | PCB | SCB | PCB | SCB | PCB | SCB | PCB | ||||

| Ali et al[7], 2019 | RCT | United States | 6 months | 25 | 25 | 61.6 ± 11.7 | 58.6 ± 21.5 | 88 | 76 | 72 | 76 | 96 | 92 | 92 | 84 | 16 | 8 |

| Liu et al[20], 2025 | RCT | China | 12 months | 130 | 128 | 63.8 ± 9.3 | 63.7 ± 8.5 | 73.1 | 75.8 | 33.8 | 41.4 | 66.9 | 70.3 | 17.7 | 14.1 | NA | NA |

| Ray et al[19], 2025 | Prospective observational study | India | 41 months | 53 | 32 | 67.19 ± 8.21 | 63.50 ± 8.54 | 86.8 | 96.9 | 73.6 | 81.3 | 71.7 | 84.4 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Scheller et al[8], 2022 | RCT | Malaysia, German, Switzerland | 12 months | 50 | 51 | 67 ± 12 | 63 ± 12 | 86 | 76 | 54 | 59 | 98 | 94 | 88 | 84 | 22 | 12 |

The same four studies reported procedural characteristics for SCB and PCB interventions. Drug-coated balloon (DCB) lengths, where reported, ranged from 23.0-29.6 mm for SCBs and 22.6-24.1 mm for PCBs, with diameters consistently around 2.91-3.31 mm for SCBs and 2.93-3.20 mm for PCBs. Dissection rates were low (0%-4% for SCBs; 0% for PCBs, where reported). Balloon inflation pressures were similar (9.3-11.6 bar for SCBs; 9.0-10.3 bar for PCBs), as were inflation times (54-60 seconds for both groups). Pre-PCI MLD in-lesion was comparable (0.81-0.86 mm for SCBs; 0.80-0.94 mm for PCBs), with in-segment MLD reported in two studies (0.81-0.82 mm for SCBs; 0.80 mm for PCBs). Procedural characteristics showed no substantial differences between SCB and PCB groups, indicating consistent interventional approaches across studies (Table 2).

| Ref. | DCB length mm | DCB diameter, mm | Dissection (%) | Balloon pressure (bar) | Balloon inflation time (s) | Minimal lumen diameter pre-PCI in-lesion (mm) | Minimal lumen diameter pre-PCI in-segment (mm) | |||||||

| SCB | PCB | SCB | PCB | SCB | PCB | SCB | PCB | SCB | PCB | SCB | PCB | SCB | PCB | |

| Ali et al[7], 2019 | N/A | N/A | 2.91 ± 0.39 | 2.93 ± 0.37 | 4 | 0% | 11.6 ± 3.2 (26) | 10.3 ± 2.8 (25) | 59.0 ± 7.1 (26) | 59.3 ± 6.1 (25) | 0.81 ± 0.34 | 0.80 ± 0.52 | 0.81 ± 0.35 | 0.80 ± 0.52 |

| Liu et al[20], 2025 | 23.0 ± 6.2 | 22.6 ± 6.2 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 0 | 0% | 9.3 ± 2.7 (149) | 9.4 ± 2.8 (141) | 58.8 ± 12.5 (149) | 57.2 ± 13.4 (141) | 0.86 ± 0.41 | 0.94 ± 0.36 | N/A | N/A |

| Ray et al[19], 2025 | 29.58 ± 7.98 | 24.11 ± 6.54 | 3.31 ± 0.39 | 3.20 ± 0.43 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | 60 | 60 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Scheller et al[8], 2022 | N/A | N/A | 3.03 ± 0.40 | 2.98 ± 0.56 | 2 | 0% | 11 ± 3 | 9 ± 3 | 58 ± 13 | 54 ± 12 | 0.85 ± 0.49 | 0.83 ± 0.49 | 0.82 ± 0.40 | 0.80 ± 0.44 |

The RoB 2.0 assessment for three randomized trials—Ali et al[7], Scheller et al[8], and Liu et al[20], gives each a "some concerns" rating, indicating possible issues. These include problems with randomization[8], sticking to the planned intervention[7,20], incomplete data[7,8], and selective reporting (all three), though outcome measurement was reliable in all (Supplementary Figures 1 and 2). On the other hand, the NOS assessment for the observational study by Ray et al[19] scores a perfect 9/9, showing high quality. It earns full marks for selecting a representative group, ensuring proper exposure and outcome checks (4 stars), controlling for differences between groups (2 stars), and accurately measuring outcomes with good follow-up (3 stars) (Supplementary Table 1). The RCTs need careful interpretation due to these concerns, but Ray et al’s study[19] is highly reliable.

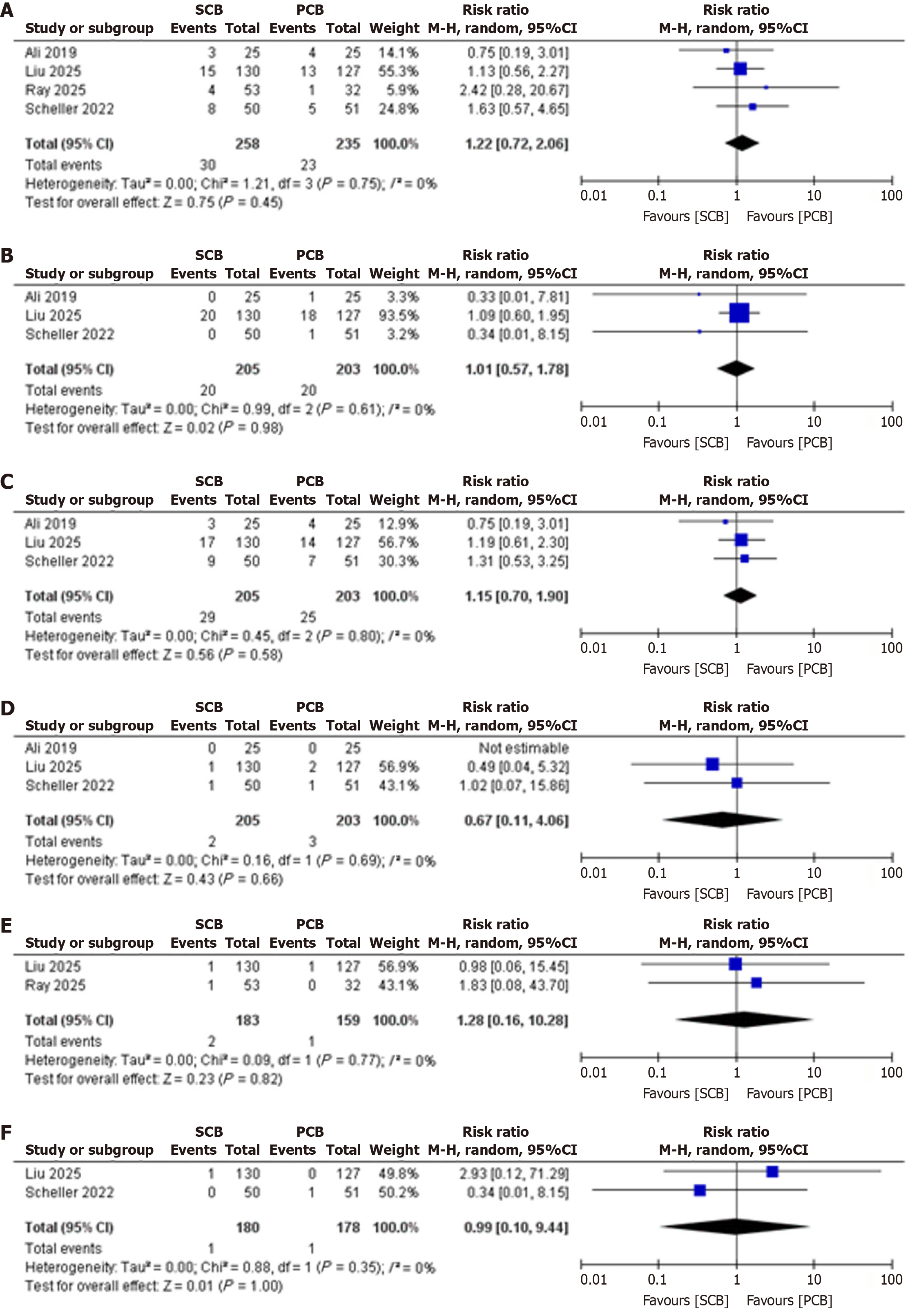

Target TLR: Four studies reported TLR, with a pooled RR of 1.22 (95%CI: 0.72-2.06; P = 0.75; I2 = 0%, indicating no heterogeneity), showing no significant difference between SCBs and PCBs (Figure 2).

Stent Thrombosis: Three studies reported stent thrombosis, with a pooled RR of 1.01 (95%CI: 0.57-1.78; P = 0.61; I2 = 0%, indicating no heterogeneity), showing no significant difference between SCBs and PCBs (Figure 2).

MACE: Three studies reported MACE, with a pooled RR of 1.15 (95%CI: 0.70-1.90; P = 0.80; I2 = 0%, indicating no heterogeneity), showing no significant difference between SCBs and PCBs (Figure 2).

All-cause mortality: Three studies reported all-cause mortality, with a pooled RR of 0.67 (95%CI: 0.11-4.06; P = 0.69; I2 = 0%, indicating no heterogeneity), showing no significant difference between SCBs and PCBs (Figure 2).

Cardiac mortality: Two studies reported cardiac mortality, with a pooled RR of 1.28 (95%CI: 0.16-10.28; P = 0.77; I2 = 0%, indicating no heterogeneity), showing no significant difference between SCBs and PCBs (Figure 2).

Myocardial infarction: Two studies reported myocardial infarction, with a pooled RR of 0.99 (95%CI: 0.10-9.44; P = 0.35; I2 = 0%, indicating no heterogeneity), showing no significant difference between SCBs and PCBs (Figure 2).

Publication bias was evaluated using funnel plots for all clinical outcomes, including target lesion revascularization, major adverse cardiovascular events, stent thrombosis, all-cause mortality, cardiac mortality, and myocardial infarction. The plots displayed symmetrical distributions of effect sizes around the pooled estimates, with no notable asymmetry observed across the included studies. This symmetry suggests the absence of significant publication bias, indicating that the meta-analysis results are unlikely to be skewed by selective reporting or non-publication of smaller studies with non-significant findings (Supplementary Figure 3).

The GRADE assessment for the meta-analysis comparing SCBs and PCBs for ISR shows "low" certainty for all outcomes (TLR, MACE, stent thrombosis, all-cause mortality, cardiac mortality, myocardial infarction). This is due to serious risk of bias from "some concerns" in RCTs (issues with randomization, intervention adherence, missing data, and selective reporting) and serious imprecision from wide confidence intervals, especially for cardiac mortality and myocardial infarction (two studies each). No concerns were found for inconsistency (I2 = 0%), indirectness, or publication bias (symmetrical funnel plots). While SCBs and PCBs appear equally effective and safe, the low certainty calls for cautious interpretation and more robust RCTs (Supplementary Table 2).

This meta-analysis of four studies, 3 RCT’s and one observational study comparing SCBs and PCBs for ISR found no significant differences in clinical outcomes, including TLR, MACE, stent thrombosis, all-cause mortality, cardiac mortality, and myocardial infarction. The consistent treatment effects across studies, indicated by the absence of heterogeneity, underscore the robustness of these findings and address the need for clarity on the comparative performance of these devices.

The equivalence in TLR outcomes suggests that SCBs and PCBs are equally effective in preventing repeat interventions driven by restenosis. This consistency is evident across individual studies, reinforcing the reliability of both devices in managing ISR[7,18,20,21]. Similarly, the lack of differences in MACE, encompassing TLR, myocardial infarction, and cardiac death, indicates comparable overall clinical efficacy. Safety profiles also appear aligned, with no notable variations in stent thrombosis, myocardial infarction, or mortality, despite the low event rates for some endpoints limiting the ability to detect subtle differences. These findings provide a clear answer to the uncertainty highlighted in prior research regarding whether SCBs can match or outperform PCBs.

The results align with and extend previous studies that established PCBs as a standard for ISR treatment[9,22]. While earlier trials like PACCOCATH-ISR and PEPCAD II demonstrated PCB superiority over conventional angioplasty, our analysis shows that SCBs achieve similar outcomes, supporting their role as a viable alternative[9,22]. Recent trials, such as SIRPAC and SABRE, further corroborate SCB efficacy, reporting performance comparable to PCBs[12,23]. Meta-analyses by Shin et al[24] and Sedhom et al[25] also found no significant differences in key outcomes, reinforcing the clinical equivalence observed here. By synthesizing high-quality randomized trials, this study helps resolve prior inconsistencies and provides a stronger evidence base for device selection.

The comparable performance of SCBs and PCBs likely stems from their shared ability to suppress neointimal hyperplasia, despite distinct pharmacological mechanisms[26]. Paclitaxel’s microtubule stabilization and sirolimus’s mTOR inhibition both effectively target smooth muscle cell proliferation[23,24,27]. Technological advancements have bridged historical differences in drug delivery. While paclitaxel’s lipophilicity enables rapid tissue uptake, modern SCB platforms, such as crystalline coatings or nanocarrier systems, enhance sirolimus retention, achieving similar therapeutic levels[28,29]. Standardized procedural factors, including balloon dimensions and inflation techniques, further minimized outcome variability. The focus on simpler ISR lesions in the included studies may have also reduced the potential for differential effects, as more complex cases might reveal device-specific nuances.

The absence of safety differences, particularly in mortality and thrombotic events, suggests that neither device poses unique risks in the coronary setting. This is particularly reassuring for PCBs, given prior concerns about long-term safety in peripheral applications[10]. The localized drug delivery of DCBs, with minimal systemic effects, likely ensures that outcomes are driven by lesion-level efficacy rather than systemic factors[30].

To assess the robustness of our findings and the potential influence of study design, we performed a sensitivity analysis excluding the observational study[19]. This analysis did not materially alter the effect estimates or statistical significance for any outcome, confirming the consistency of our results. This approach is recommended even in the absence of statistical heterogeneity (I2 = 0), to account for potential design- or bias-related differences not captured by the heterogeneity metric.

These findings support the interchangeable use of SCBs and PCBs for ISR, empowering clinicians to choose based on practical considerations such as device availability, operator familiarity, or patient-specific lesion characteristics. Both DCBs offer a compelling alternative to repeat stenting, reducing the need for additional stent layers and potentially lowering long-term complications[31]. The equivalence in safety outcomes alleviates concerns about choosing one device over the other, allowing flexibility in tailoring treatment to individual needs. For high-risk patients, such as those with diabetes or small vessels, either device appears suitable, though further data are needed to confirm this.

The analysis faced constraints that warrant consideration. The inclusion of only four studies, with fewer contributing to certain outcomes like myocardial infarction, may have limited statistical power. Not all studies reported every outcome, resulting in varying sample sizes for different endpoints that may affect the precision and certainty of the pooled estimates. Short follow-up durations, typically one year, restrict insights into long-term durability, particularly for SCBs, which may exhibit delayed benefits due to sirolimus’s mechanism[32]. Variations in MACE definitions across studies could introduce minor inconsistencies, though the lack of heterogeneity suggests minimal impact; this heterogeneity in outcome definitions may nonetheless affect comparability and interpretation. The predominance of simple ISR lesions limits generalizability to more complex cases. Device-specific differences, such as coating technologies and the lack of detailed information on manufacturers in some included studies, were not fully explored due to limited reporting. Finally, the small number of studies precluded formal publication bias assessment, though visual funnel plot symmetry suggests low risk. Risk of bias concerns also persist due to issues in randomization and protocol adherence in some randomized controlled trials, which lowers the overall certainty (GRADE) of the evidence.

To build on these findings, larger randomized trials with extended follow-up are essential to evaluate long-term outcomes, particularly for SCBs, which may offer sustained benefits[32]. Studies targeting high-risk populations, such as those with diffuse ISR or comorbidities, could identify subgroups where one device may outperform the other. Comparative analyses of specific DCB platforms and standardized outcome definitions would enhance precision. Additionally, there is a crucial need for comprehensive cost-effectiveness studies comparing both stent types, which could guide device selection in diverse healthcare systems and address practical barriers to adoption. Such economic evaluations should consider both short- and long-term healthcare costs alongside clinical effectiveness Future research integrating rigorous economic analysis alongside clinical endpoints would provide balanced evidence to optimize treatment strategies.

This meta-analysis demonstrates that SCBs and PCBs offer equivalent efficacy and safety for coronary ISR, providing clear, evidence-based guidance for interventional cardiologists. By confirming the clinical equivalence of these devices, the study supports their flexible use in practice, tailored to logistical and patient-specific factors. Future research should focus on long-term outcomes and high-risk cohorts to further refine ISR management strategies.

| 1. | Alfonso F, Pérez-Vizcayno MJ, Cárdenas A, García Del Blanco B, Seidelberger B, Iñiguez A, Gómez-Recio M, Masotti M, Velázquez MT, Sanchís J, García-Touchard A, Zueco J, Bethencourt A, Melgares R, Cequier A, Dominguez A, Mainar V, López-Mínguez JR, Moreu J, Martí V, Moreno R, Jiménez-Quevedo P, Gonzalo N, Fernández C, Macaya C; RIBS V Study Investigators, under the auspices of the Working Group on Interventional Cardiology of the Spanish Society of Cardiology. A randomized comparison of drug-eluting balloon versus everolimus-eluting stent in patients with bare-metal stent-in-stent restenosis: the RIBS V Clinical Trial (Restenosis Intra-stent of Bare Metal Stents: paclitaxel-eluting balloon vs. everolimus-eluting stent). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:1378-1386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 18.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cutlip DE, Windecker S, Mehran R, Boam A, Cohen DJ, van Es GA, Steg PG, Morel MA, Mauri L, Vranckx P, McFadden E, Lansky A, Hamon M, Krucoff MW, Serruys PW; Academic Research Consortium. Clinical end points in coronary stent trials: a case for standardized definitions. Circulation. 2007;115:2344-2351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4265] [Cited by in RCA: 4763] [Article Influence: 250.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dangas GD, Claessen BE, Caixeta A, Sanidas EA, Mintz GS, Mehran R. In-stent restenosis in the drug-eluting stent era. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1897-1907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 523] [Cited by in RCA: 621] [Article Influence: 41.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Abdelaziz A, Atta K, Hafez AH, Elsayed H, Ibrahim AA, Abdelaziz M, Kadhim H, Mechi A, Elaraby A, Ezzat M, Fadel A, Nouh A, Ibrahim RA, Ellabban MH, Bakr A, Nasr A, Suppah M. Drug-coated balloons versus drug-eluting stents in patients with in-stent restenosis: An updated meta-analysis with trial sequential analysis. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2024;19:624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bangalore S, Toklu B, Patel N, Feit F, Stone GW. Newer-Generation Ultrathin Strut Drug-Eluting Stents Versus Older Second-Generation Thicker Strut Drug-Eluting Stents for Coronary Artery Disease. Circulation. 2018;138:2216-2226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 34.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Meraj PM, Jauhar R, Singh A. Bare Metal Stents Versus Drug Eluting Stents: Where Do We Stand in 2015? Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med. 2015;17:393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ali RM, Abdul Kader MASK, Wan Ahmad WA, Ong TK, Liew HB, Omar AF, Mahmood Zuhdi AS, Nuruddin AA, Schnorr B, Scheller B. Treatment of Coronary Drug-Eluting Stent Restenosis by a Sirolimus- or Paclitaxel-Coated Balloon. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2019;12:558-566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Scheller B. Drug-coated balloons--the new gold standard for treatment of coronary in-stent restenosis? Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2012;13:257-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Unverdorben M, Vallbracht C, Cremers B, Heuer H, Hengstenberg C, Maikowski C, Werner GS, Antoni D, Kleber FX, Bocksch W, Leschke M, Ackermann H, Boxberger M, Speck U, Degenhardt R, Scheller B. Paclitaxel-coated balloon catheter versus paclitaxel-coated stent for the treatment of coronary in-stent restenosis: the three-year results of the PEPCAD II ISR study. EuroIntervention. 2015;11:926-934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Katsanos K, Spiliopoulos S, Kitrou P, Krokidis M, Karnabatidis D. Risk of Death Following Application of Paclitaxel-Coated Balloons and Stents in the Femoropopliteal Artery of the Leg: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e011245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 711] [Cited by in RCA: 731] [Article Influence: 91.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (18)] |

| 11. | Haase T, Speck U, Bienek S, Löchel M, Brunacci N, Gemeinhardt O, Schütt D, Bettink S, Kelsch B, Scheller B, Schnorr B. Drug-Coated Balloons: Drugs Beyond Paclitaxel? Front Biosci (Landmark Ed). 2022;27:283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cortese B, Caiazzo G, Di Palma G, De Rosa S. Comparison Between Sirolimus- and Paclitaxel-Coated Balloon for Revascularization of Coronary Arteries: The SIRPAC (SIRolimus-PAClitaxel) Study. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2021;28:1-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cortese B, Malakouti S, Mazhar W, Leontin Lazar F, Munjal A, Ketchanji Mougang Y. Long-term benefits of drug-coated balloons for coronary artery revascularization. Minerva Cardiol Angiol. 2024;72:506-516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8:336-341. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9207] [Cited by in RCA: 8362] [Article Influence: 522.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 15. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44932] [Cited by in RCA: 51894] [Article Influence: 10378.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 16. | Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, Cates CJ, Cheng HY, Corbett MS, Eldridge SM, Emberson JR, Hernán MA, Hopewell S, Hróbjartsson A, Junqueira DR, Jüni P, Kirkham JJ, Lasserson T, Li T, McAleenan A, Reeves BC, Shepperd S, Shrier I, Stewart LA, Tilling K, White IR, Whiting PF, Higgins JPT. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019;366:l4898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6581] [Cited by in RCA: 18876] [Article Influence: 2696.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle-Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603-605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8858] [Cited by in RCA: 13641] [Article Influence: 852.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Scheller B, Mangner N, Abdul Kader MASK, Wan Ahmad WA, Jeger R, Wöhrle J, Ong TK, Liew HB, Gori T, Mahfoud F, Nuruddin AA, Woitek F, Abidin IZ, Schwenke C, Schnorr B, Mohd Ali R. Combined Analysis of Two Parallel Randomized Trials of Sirolimus-Coated and Paclitaxel-Coated Balloons in Coronary In-Stent Restenosis Lesions. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2022;15:e012305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ray S, Bandyopadhyay S, Bhattacharjee P, Mukherjee P, Karmakar S, Bose P, Choudhury B, Paul D, Karak A. Drug-coated balloon in patients with in-stent restenosis: A prospective observational study. Indian Heart J. 2025;77:105-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Liu H, Li Y, Fu G, An J, Chen S, Zhong Z, Liu B, Qiu C, Ma L, Cong H, Li H, Tong Q, He B, Jin Z, Zhang J, Yuan H, Qiu M, Zhang R, Han Y. Sirolimus- vs Paclitaxel-Coated Balloon for the Treatment of Coronary In-Stent Restenosis: The SIBLINT-ISR Randomized Trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2025;18:963-971. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kundu A, Moliterno DJ. Drug-Coated Balloons for In-Stent Restenosis-Finally Leaving Nothing Behind for US Patients. JAMA. 2024;331:1011-1012. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Scheller B, Hehrlein C, Bocksch W, Rutsch W, Haghi D, Dietz U, Böhm M, Speck U. Treatment of coronary in-stent restenosis with a paclitaxel-coated balloon catheter. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2113-2124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 568] [Cited by in RCA: 613] [Article Influence: 30.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Verheye S, Vrolix M, Kumsars I, Erglis A, Sondore D, Agostoni P, Cornelis K, Janssens L, Maeng M, Slagboom T, Amoroso G, Jensen LO, Granada JF, Stella P. The SABRE Trial (Sirolimus Angioplasty Balloon for Coronary In-Stent Restenosis): Angiographic Results and 1-Year Clinical Outcomes. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10:2029-2037. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Shin D, Singh M, Shlofmitz E, Scheller B, Latib A, Kandzari DE, Zaman A, Mylotte D, Dakroub A, Malik S, Sakai K, Jeremias A, Moses JW, Shlofmitz RA, Stone GW, Ali ZA. Paclitaxel-coated versus sirolimus-coated balloon angioplasty for coronary artery disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2024;104:425-436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sedhom R, Hamed M, Elbadawi A, Mohsen A, Swamy P, Athar A, Bharadwaj AS, Prasad V, Elgendy IY, Alfonso F. Outcomes With Limus- vs Paclitaxel-Coated Balloons for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2024;17:1533-1543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wessely R. New drug-eluting stent concepts. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2010;7:194-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Parry TJ, Brosius R, Thyagarajan R, Carter D, Argentieri D, Falotico R, Siekierka J. Drug-eluting stents: sirolimus and paclitaxel differentially affect cultured cells and injured arteries. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;524:19-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Clever YP, Peters D, Calisse J, Bettink S, Berg MC, Sperling C, Stoever M, Cremers B, Kelsch B, Böhm M, Speck U, Scheller B. Novel Sirolimus-Coated Balloon Catheter: In Vivo Evaluation in a Porcine Coronary Model. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;9:e003543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Lemos PA, Farooq V, Takimura CK, Gutierrez PS, Virmani R, Kolodgie F, Christians U, Kharlamov A, Doshi M, Sojitra P, van Beusekom HM, Serruys PW. Emerging technologies: polymer-free phospholipid encapsulated sirolimus nanocarriers for the controlled release of drug from a stent-plus-balloon or a stand-alone balloon catheter. EuroIntervention. 2013;9:148-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lazar FL, Onea HL, Olinic DM, Cortese B. A 2024 scientific update on the clinical performance of drug-coated balloons. AsiaIntervention. 2024;10:15-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Alfonso F, Scheller B. State of the art: balloon catheter technologies - drug-coated balloon. EuroIntervention. 2017;13:680-695. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 32. | Camaj A, Leone PP, Colombo A, Vinayak M, Stone GW, Mehran R, Dangas G, Kini A, Sharma SK. Drug-Coated Balloons for the Treatment of Coronary Artery Disease: A Review. JAMA Cardiol. 2025;10:189-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 27.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/