Published online Mar 20, 2026. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v16.i1.110159

Revised: June 21, 2025

Accepted: July 16, 2025

Published online: March 20, 2026

Processing time: 255 Days and 19.1 Hours

Substance use (SU) and diabetes mellitus (DM) are major public health concerns and leading causes of mortality in the United States. However, trends examining their combined impact remain limited. This study analyzed mortality trends related to SU and DM from 1999-2022, focusing on demographic disparities, geographic patterns, and substance-specific contributions using Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data.

To examine trends in DM-related mortality involving SU in the United States from 1999-2022, focusing on demographic and geographic disparities and to identify high-risk groups to guide equitable public health interventions.

Mortality data were obtained from death certificate records. Age-adjusted mor

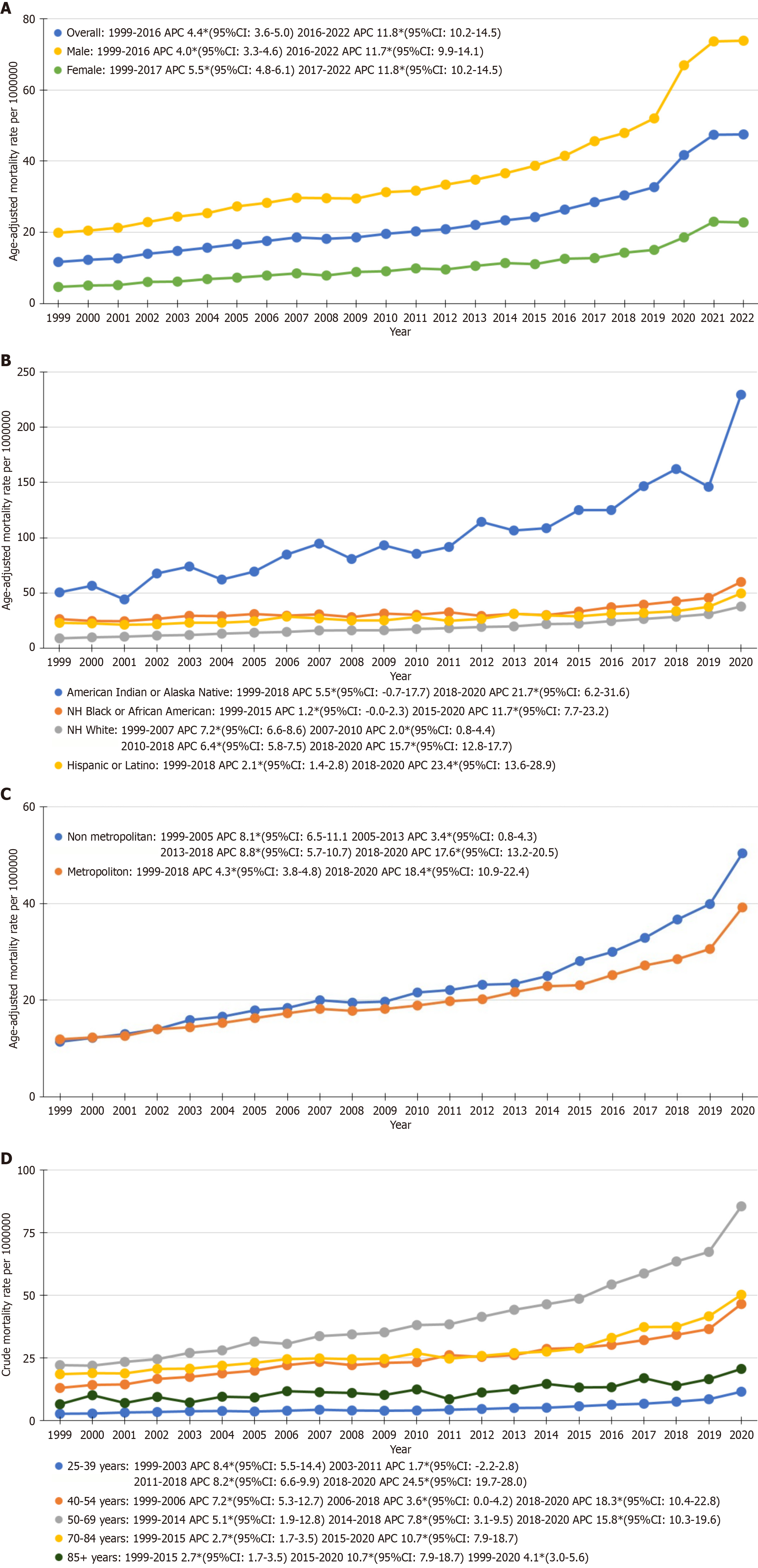

From the years 1999-2022 127659 adult deaths were disclosed with SU and DM as the primary cause. The overall AAMR rose with an APC of 4.4% (95%CI: 3.6-5.0) from 1999-2016, accelerating to 11.8 (95%CI: 10.2-14.5) from 2016-2022. Gender disparities showed males having higher AAMRs throughout the study period as compared with females. Among racial groups there was a significantly higher AAMR consistently for American Indian/Alaska Natives compared with other races. Geographic analysis showed the highest AAMR in the western states (32/1000000) and pronounced rural increases (APC: 17.6%, 95%CI: 13.2–20.5) after 2018. Alcohol use was the leading contributor (71861 deaths), followed by cocaine and stimulant use.

This study revealed alarming increases in mortality linked to SU and DM, with widening demographic and geographic disparities. Targeted strategies addressing SU and DM within vulnerable populations are urgently needed to reduce preventable deaths and health inequities.

Core Tip: Substance use-related diabetes mortality rose sharply from 1999-2022, disproportionately affecting males, American Indian/Alaska Native populations, and western states. A pronounced surge during 2018-2020, especially among Hispanic/Latino and rural populations, underscores the need for equity-focused healthcare policies and culturally informed interventions.

- Citation: Khan SMI, Waqas M, Khawar M, Batool A, Komel A, Ashraf MA, Saifullah M, Rana I. Temporal trends and disparities in substance use and diabetes mellitus-related mortality in the United States (1999-2022). World J Methodol 2026; 16(1): 110159

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v16/i1/110159.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v16.i1.110159

Substance use (SU) is a pressing dilemma in the United States and worldwide[1]. In 2020 40.3 million people were diagnosed with SU based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-5 criteria[2]. Statics showed that intensive care unit admissions and mortality caused by SU are on an increasing trend in older adults aged more than 65 years[1].

Among all endocrine disorders SU is most related to the development of diabetes mellitus (DM) that can easily be explained by rapid cell damage, pancreatic beta cell dysfunction, and glucose dysregulation due to increased oxidative stress and decreased antioxidant activity caused by SU[3]. In the last four decades, the number of adults living with DM has increased four-fold, but the data regarding its complications and mortality is inadequate[4]. Likewise, the relationship between SU and DM is quite evident in the literature. However, the trend of SU and DM-related mortality differing by sex and ethnicity within the United States has not been well studied. To bridge this knowledge gap, we analyzed trends in SU and DM-related mortality using the Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER) database from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

For obtaining and computation of data for our study, we utilized the CDC WONDER database, which delivers information provided by the National Center for Health Statistics for determining annual mortality trends for adults (25-85+ years of age)[5]. The dataset for annual mortality trends categorized by overall trends and sex was extracted from 1999-2022, whereas datasets categorized by race/ethnicity, state, census region, urban-rural classification, age stratified mortality trends, and mortality trends stratified by SU contributing to DM was obtained from 1999-2020. The dataset is updated annually based on death certificates of United States residents and include information about the primary cause of death and related demographic details. By utilizing the final Multiple Cause of Death Public Use Record and the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes, including for SU (Supplementary Table 1) and E10-E14 for DM. We included deaths only when both an SU-related ICD-10 code and a DM code (E10-E14) were listed on the same death certificate, either as underlying or contributing causes of death. Institutional Review Board approval was not necessary for our study as the study was based on anonymized and publicly available data. Additionally, the study was conducted in accordance with STROBE guidelines[6].

The extensive dataset used incorporated a wide variety of demographic variables, including race/ethnicity, sex groups, census region, state, age group, and type of SU. The sex categories were classified as male and female. The race/ethnicity groups were labelled as non-Hispanic (NH) White, NH Black or African American, NH Other (including NH American Indian or Alaska Native), and Hispanic or Latino. We also determined annual mortality trends related to SU and DM, considering state-specific variations, census regions in the United States (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West), and urban-rural classification followed the 2013 National Center for Health Statistics scheme: (Rural: Micropolitan and noncore regions; urban: Large central metro, large fringe metro, medium metro, and small metro regions)[7].

SU and DM associated age adjusted mortality rates (AAMRs) were determined. For age group stratified-based analysis, crude mortality rates were obtained. AAMRs and crude mortality rates track changes in the age distribution of the population for data analysis purposes and were extrapolated using the direct method of adjustment with the 2000 standard population[8]. We employed Joinpoint Regression Program (Joinpoint version 5.0.2, National Cancer Institute) to calculate age-adjusted mortality trends from 1999-2022[9]. This program uses serial permutation tests to analyze repeated time trends and identifies up to one inflection point where the mortality rate change is statistically significantly different. Following this, the program calculates the weighted average annual percentage change (APC) for each time segment in the AAMR along with the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). An APC estimate was calculated to indicate an increase or decrease if the slope of the trend significantly differed from zero; otherwise, the trend was considered stable. A pairwise comparison was performed to assess whether the differences in APCs were statistically significant across various subgroups (sex, race, census regions, and urbanization). A P value < 0.05 was used to indicate a statistically significant change in the trend.

Mortality rates across all demographic groups demonstrated notable trends across the study period. From 1999-2022 there were 127659 deaths for adults (25-85+ years of age) due to SU and DM (Supplementary Table 2). From 1999-2022, males demonstrated a total of 98002 deaths whereas females had 29567 deaths during this period. In race stratified groups from 1999-2020 the total recorded deaths for American Indians or Alaska Native, NH Black, NH White, and Hispanic or Latino populations were 3948 deaths, 18111 deaths, 65313 deaths, and 14399 deaths, respectively (Supplementary Table 3). The overall AAMR rate exhibited an increase with an average APC of 4.4 (95%CI: 3.6-5.0) from 1999 to 2016. This increase rose rapidly between 2016 and 2022 with an APC of 11.8 (95%CI: 10.2 to 14.5) (Figure 1A, Supplementary Table

The age group 25-39 years showed notable increases with an APC of 8.4 (95%CI: 5.5-14.4) between 1999-2003, 1.7 (95%CI: -2.2-2.8) from 2003-2011, and 8.2 (95%CI: 6.6-9.9) from 2011-2018 (Figure 1B and Supplementary Table 4). A prominent surge of 24.5 (95%CI: 19.7-28.0) was observed in 2018-2020. The 40-54 year age group showed an APC of 7.2 (95%CI: 5.3-12.7) during 1999-2006, followed by 3.6 (95%CI: 0.0-4.2) from 2006-2018 and a significant surge to 18.3 (95%CI: 10.4-22.8) in 2018-2020. The 50-69 year age group demonstrated an APC of 5.1 (95%CI: 1.9-12.8) between 1999-2014, 7.8 (95%CI: 3.1-9.5) from 2014-2018, and 15.8 (95%CI: 10.3–19.6) in 2018-2020. The 70-84 year age group showed a more gradual increase with an APC of 2.7 (95%CI: 1.7-3.5) during 1999-2015, followed by a significant increase to 10.7 (95%CI: 7.9-18.7) in 2015-2020. For the 85+ age group, an APC of 2.7 (95%CI: 1.7-3.5) was observed from 1999-2015, and the rate increased notably to 10.7 (95%CI: 7.9-18.7) during 2015-2020.

AAMRs for males exhibited an APC of 4.0 (95%CI: 3.3-4.7) from 1999-2016 (Figure 1C). From 2016-2022 the rate increased to an APC of 11.7 (95%CI: 9.9-14.1). AAMRs for females demonstrated a similar increase compared with men. From 1999-2017 the APC was 5.3 (95%CI: 4.6-6.0), followed by a much rapid rise from 2017-2022 with an APC of 11.8 (95%CI: 10.5-14.5). Throughout the study period, males were noted to have higher AAMRs compared with females (Supplementary Table 5).

For American Indian or Alaska Natives, the AAMRs increased steadily with an APC of 5.5 (95%CI: -0.7-17.7) from 1999-2018 (Figure 1D and Supplementary Table 6). From 2018-2020 the rate rose significantly with an APC of 21.7 (95%CI: 6.2-31.6). In cases of NH Blacks or African Americans, the rate remained constant from 1999-2015 with an APC of 1.2 (95%CI: -0.0-2.3). Between 2015-2020 a prominent increase was observed with an APC of 11.7 (95%CI: 7.7-23.2). In the NH White population, mortality rates increased between 1999-2007 at an APC of 7.2 (95%CI: 6.6-8.6). After this a gradual increase was seen from 2007-2010 with an APC of 2.0 (95%CI: 0.8-4.4). A gradual growth from 2010-2018 was observed with an APC of 6.4 (95%CI: 5.8-7.5). The sharpest rise occurred from 2018-2020 with an APC of 15.7 (95%CI: 12.8-17.7). Mortality rates for Hispanic or Latino populations showed a slower increase from 1999-2018 with an APC of 2.1 (95%CI: 1.4-2.8). This trend changed dramatically from 2018-2020 with a rapid increase in APC of 23.4 (95%CI: 13.6-28.9).

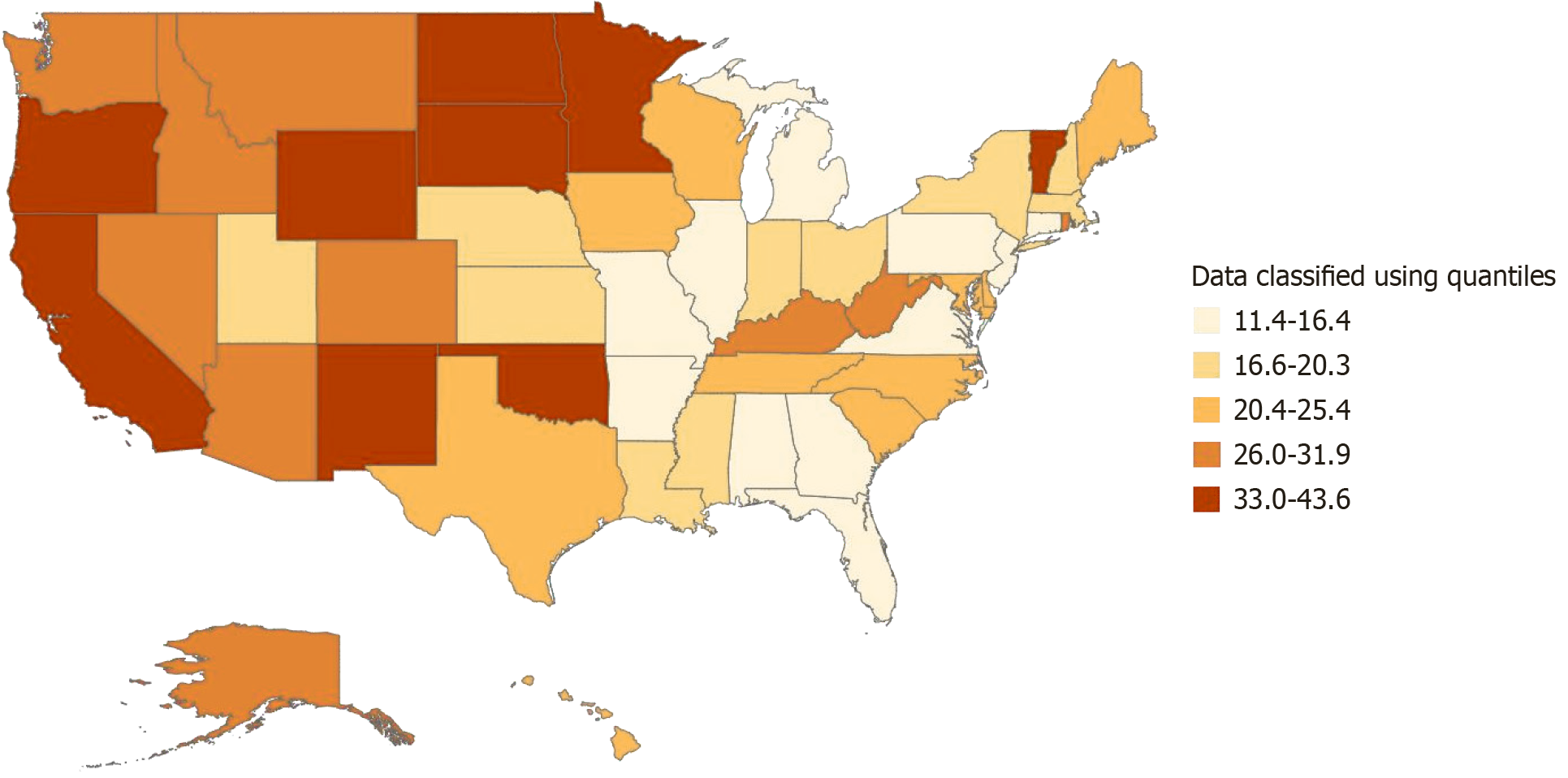

Substantial variation in AAMRs across the United States was noticed, ranging from a low of (11.4) in Alabama to a high of (43.6) in Oklahoma (Figure 2 and Supplementary Table 7). States in the top 90th percentile with the highest mortality rates included Oklahoma (43.6), Oregon (43.0), Vermont (39.5), New Mexico (38.3), North Dakota (35.7), Minnesota (34.5), Wyoming (34.2), California (33.3), and South Dakota (33.0). In contrast states in the lowest 10th percentile with the lowest mortality rates were Alabama (11.4), Illinois (12.2), New Jersey (12.2), Connecticut (12.5), and Virginia (13.8).

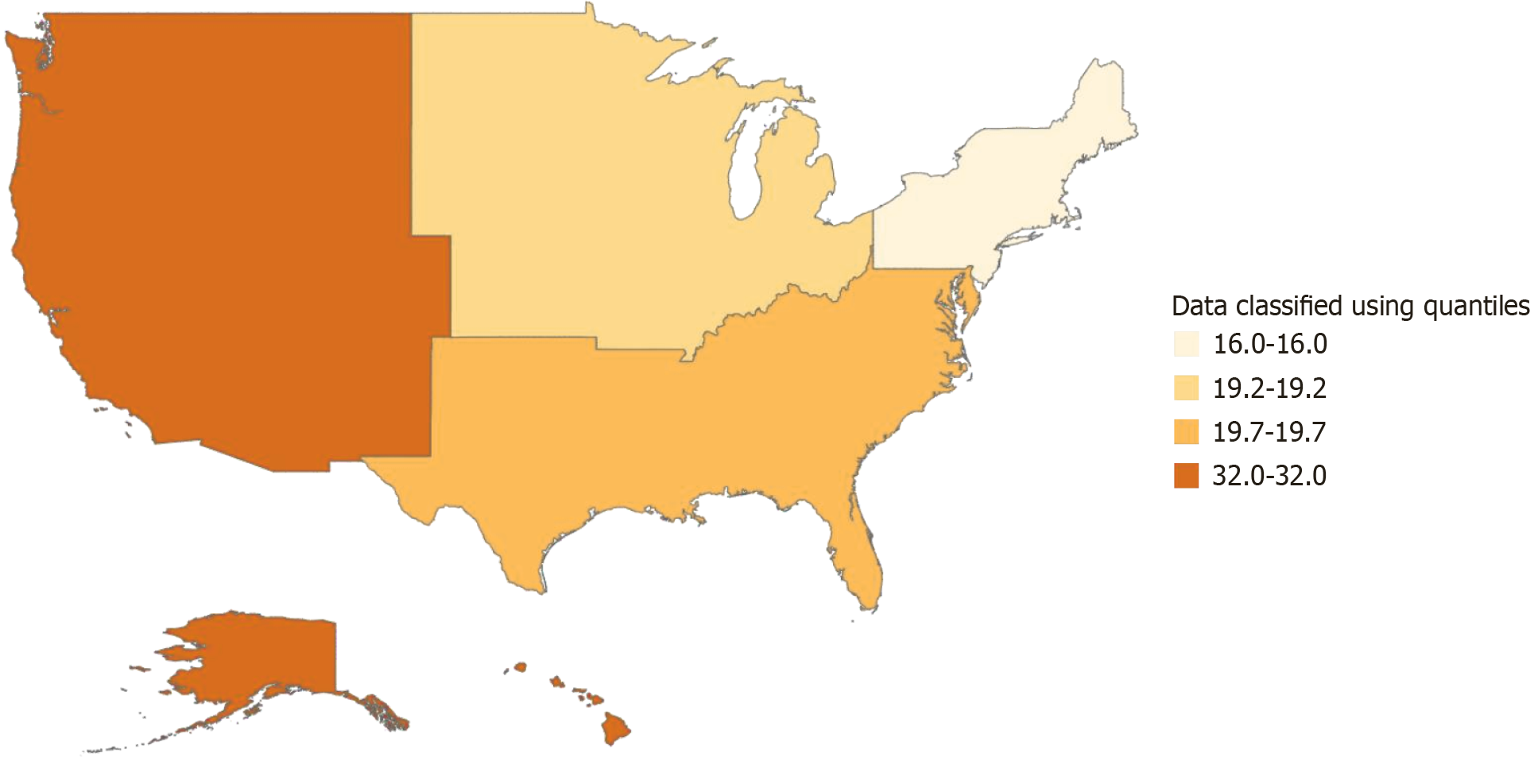

Noticeable variations across census regions were observed as well. The Northeast region had the lowest AAMR at (16.0), followed by the Midwest with a rate of (19.2) and the South with a slightly higher rate of (19.7). The West region had the highest mortality rate at (32.0), twice that of the Northeast region (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 8).

For non-metropolitan areas the AAMR indicated an APC of 8.1 (95%CI: 6.5-11.1) from 1999-2005 and reduced to an APC of 3.4 (95%CI: 0.8-4.3) between 2005-2013 (Figure 4 and Supplementary Table 9). The rate then increased with an APC of 8.8 (95%CI: 5.7-10.7) from 2013-2018 and further accelerated with an APC of 17.6 (95%CI: 13.2-20.5) from 2018-2020. For metropolitan areas the AAMR increased at an APC of 4.3 (95%CI: 3.8-4.8) from 1999-2018 followed by a rapid increase with an APC of 18.4 (95%CI: 10.9-22.4) from 2018-2020.

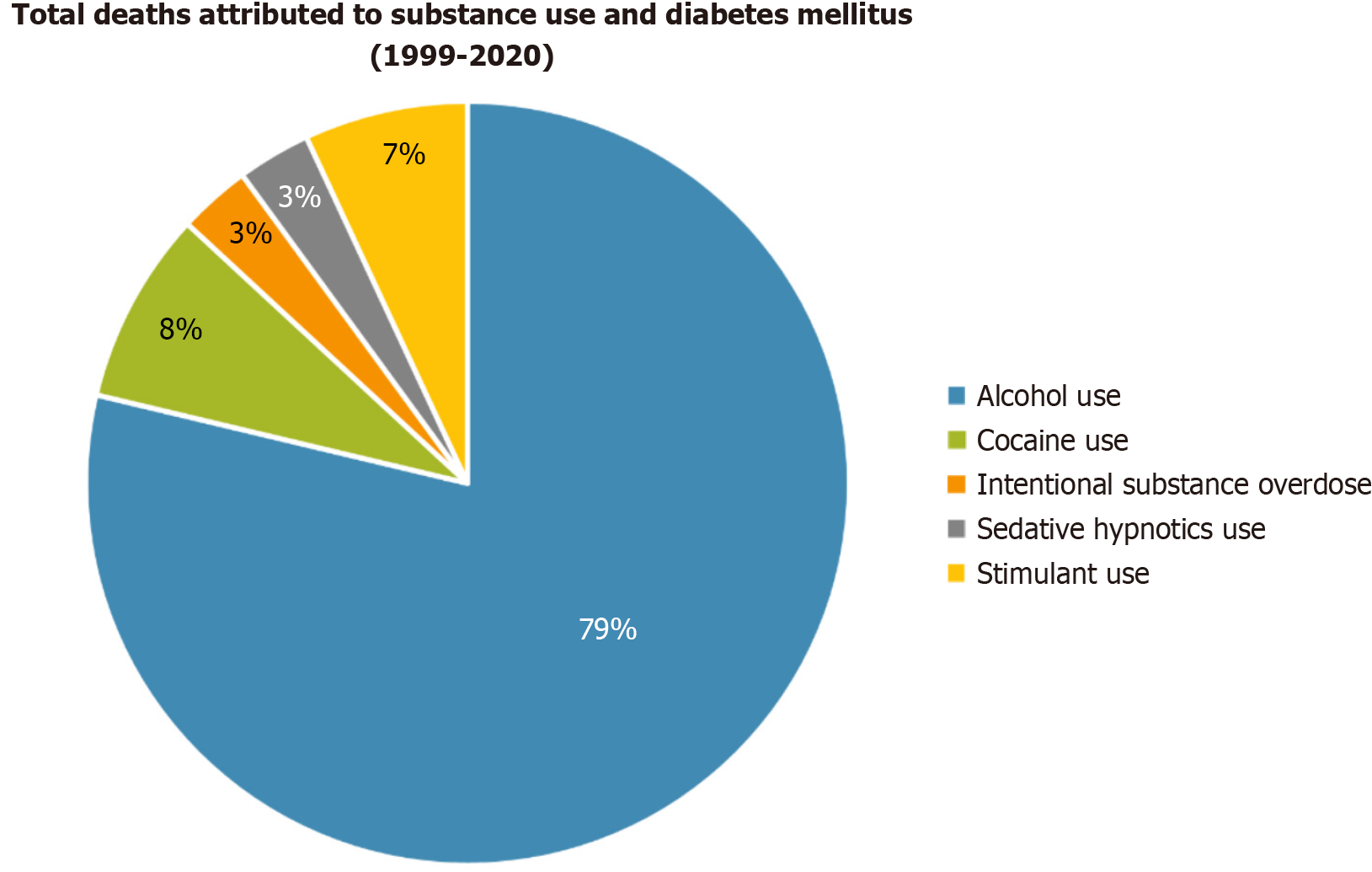

We also noticed significant death rates in the United States population based on the type of SU. Alcohol use was the biggest contributor to deaths from 1999-2020 with total deaths amounting to 71861 deaths (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 10). This was followed by cocaine use with cumulative deaths from 1999-2020 totaling to 7450 deaths. These SU were followed by stimulant use, sedative hypnotics use, and intentional substance overdose with total deaths from 1999-2020, equaling to 6334 deaths, 2839 deaths, and 2803 deaths, respectively.

In this study we examined SU and DM-related mortality trends in the United States from 1999-2022, highlighting significant disparities across sex, race/ethnicity, age, geographic regions, and urbanization status. This study explored the underlying causes of these disparities, including social determinants, healthcare access, and biological mechanisms while proposing targeted public health interventions to address the rising mortality rates and inequities.

Race-stratified mortality rates underscored persistent inequities with American Indian/Alaska Native populations exhibiting the highest AAMRs from 1999-2018. Research suggests this trend is driven by historical and structural factors, including intergenerational trauma from colonization and forced displacement, which are linked to elevated rates of SU and mental health challenges[10]. Systemic underfunding of the Indian Health Service, which provides healthcare to American Indian/Alaska Native communities, exacerbates these issues by limiting access to integrated DM and SU treatment[11]. Cultural stigma surrounding mental health and SU further impedes care-seeking behaviors[11].

For Hispanic/Latino populations a dramatic APC surge (23.4%, 95%CI: 13.6-28.9) from 2018-2020 likely reflects pandemic-era challenges, such as job insecurity, language barriers in accessing DM care, and a higher prevalence of preexisting metabolic conditions like obesity and prediabetes as documented in CDC reports[12]. These factors, compounded by restricted healthcare access during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, intensified mortality trends. Addressing these disparities requires culturally sensitive interventions, such as community-led health programs for American Indian/Alaska Native populations and bilingual DM education for Hispanic/Latino communities.

Both males and females were affected by SU-DM mortality, with males consistently showing higher AAMRs throughout the study period. However, females exhibited a slightly higher APC from 2017-2022 (11.8%, 95%CI: 10.5-14.5 vs 11.7% for males), potentially reflecting shifts in societal roles and increased daily stressors. This aligns with findings by Matarazzo et al[13], who reported a 2.5-fold increase in alcohol-related mortality rate ratios among females. The lower likelihood of females seeking treatment for alcohol use may further contribute to this trend[14]. Conversely, Okafor et al[15] found that self-reported marijuana use was associated with a reduced risk of type 2 DM in specific cohorts, suggesting substance-specific variations that warrant further investigation. Gender-specific interventions, such as female-focused SU screening and support groups, could mitigate these trends.

It seems likely that significant geographic disparities emerged, with the West region, including states like Oklahoma (AAMR: 43.6), Oregon (AAMR: 43.0), and New Mexico (AAMR: 38.3), consistently exhibiting the highest AAMRs. These trends may reflect a higher prevalence of SU disorders, limited access to integrated DM care, and variations in state-level SU treatment policies[16]. The outlier status of Oklahoma could be linked to socioeconomic factors, such as high living costs and underfunded healthcare systems.

In rural areas the APC surged to 17.6% (95%CI: 13.2-20.5) from 2018-2020, driven by structural healthcare challenges, including a scarcity of endocrinologists, limited SU treatment facilities, and transportation barriers[16,17]. Urban counties reported lower mortality rates, likely due to better healthcare access[18]. Interventions such as telemedicine expansion for DM management, mobile health clinics, and community-based SU-DM programs tailored to rural needs could bridge these gaps. Increased investment in preventive care and region-specific health initiatives is critical for high-mortality states like those in the West region.

The evidence leans toward alcohol being the dominant contributor to SU-DM deaths (71861 deaths from 1999-2020), driven by its biological effects on DM pathogenesis. Chronic alcohol use induces pancreatic beta cell toxicity, insulin resistance, and an increased risk of diabetic ketoacidosis through oxidative stress and glucose dysregulation[19]. Cocaine (7450 deaths) and stimulants (6334 deaths) also contributed significantly, exacerbating DM outcomes through hyper

The impact of multiple SU should also be considered as co-use of agents such as alcohol and cocaine can have synergistic effects on DM outcomes. Evidence suggests that polysubstance use may amplify cardiovascular and metabolic risks, such as increased catecholamine release, oxidative stress, and myocardial injury, especially when stimulants are combined with alcohol. Although our study focused on single substance-attributed mortality due to data constraints, this represents a limitation as overlapping SU is common and often underreported on death certificates. Future research with more granular toxicology or clinical data is needed to explore these interactions and their additive or multiplicative effects on SU-DM mortality[21].

The surge in AAMRs across all demographic groups in 2020, coinciding with the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, likely reflects indirect consequences such as increased stress, social isolation, and restricted healthcare access. This aligns with Terechin et al[22], who reported a 10.3% mortality rate among patients with alcohol use disorder during the pandemic. The elevated AAMRs of the West region may be linked to higher baseline SU prevalence, while rural areas faced compounded challenges due to limited healthcare infrastructure. Psychiatric comorbidities, which surfaced during the pandemic, likely exacerbated SU-DM mortality as noted by Wu et al[23].

Age group analysis revealed concerning trends among younger adults (25-39 years and 40-54 years), whose APC surged from 2018-2020, likely due to greater substance access and risk-taking behaviors. Older adults (50-69 years and 70-84 years) showed more gradual increases although baby boomers exhibited higher SU prevalence compared with prior generations that was influenced by cultural shifts in the 1960s and 1970s[24]. Socioeconomic factors, such as low income (< $35000 annually) and limited healthcare access in rural areas, further exacerbated these trends, particularly for older adults who defer care due to costs[16].

Comprehensive public health interventions must address the root causes of SU-DM mortality disparities. Enhanced screening for SU, improved access to DM care, and community-based initiatives targeting high-risk groups (e.g., American Indian/Alaska Native, Hispanic/Latino, and rural populations) are priorities. Policymakers should allocate resources to address socioeconomic determinants, such as healthcare funding in under-resourced states and trans

Reliance on the CDC WONDER database, which uses death certificates, may introduce errors due to misinterpretation or incomplete data. Future studies could incorporate electronic medical records with patient consent for more comprehensive data. Demographic data limitations prevent in-depth analysis of variables like healthcare access or treatment adherence, potentially biasing results. Incorporating socioeconomic status and healthcare access variables could enhance accuracy. The use of ICD-10 codes may lead to underreporting, and expanding the range of codes could capture more data. While this study identified strong associations between specific substances and DM-related mortality, causality cannot be inferred from mortality count data alone. Future research utilizing causal inference methods, such as Mendelian randomization, may help clarify whether SU directly contributes to DM pathogenesis and mortality. Additionally, our study did not include a comparison group of DM-related deaths without documented SU, limiting our ability to estimate the excess mortality risk attributable solely to SU. Previous research indicated that patients with both DM and SU disorder experience worse outcomes, such as higher hospitalization rates and mortality, compared with those with DM alone. Future investigations using matched control cohorts or longitudinal electronic health data are needed to delineate the independent impact of SU on DM mortality[25].

SU-DM mortality increased across all demographic groups from 1999-2022, with males, American Indian/Alaska Native populations, and western states showing the highest AAMRs. The 2018-2020 APC surge, particularly among Hispanic/Latino populations and rural areas, highlighted the impact of pandemic-era challenges. Proper allocation of medical resources and targeted interventions addressing structural, cultural, and socioeconomic determinants are crucial for mitigating these unequal mortality trends.

| 1. | Bolds M. Substance Use Disorder in Critical Care. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2023;35:469-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Swimmer KR, Sandelich S. Substance Use Disorder. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2024;42:53-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Axelsson S, Hjorth M, Ludvigsson J, Casas R. Decreased GAD(65)-specific Th1/Tc1 phenotype in children with Type 1 diabetes treated with GAD-alum. Diabet Med. 2012;29:1272-1278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ali MK, Pearson-Stuttard J, Selvin E, Gregg EW. Interpreting global trends in type 2 diabetes complications and mortality. Diabetologia. 2022;65:3-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 241] [Article Influence: 60.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multiple Cause of Death Data on CDC WONDER [Internet]. [cited 25 December 2024]. Available from: https://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd.html. |

| 6. | von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453-1457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6805] [Cited by in RCA: 13712] [Article Influence: 721.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 7. | Ingram DD, Franco SJ. 2013 NCHS Urban-Rural Classification Scheme for Counties. Vital Health Stat 2. 2014;1-73. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Anderson RN, Rosenberg HM. Age standardization of death rates: implementation of the year 2000 standard. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 1998;47:1-16, 20. [PubMed] |

| 9. | National Center for Health Statistics. Joinpoint trend analysis software - Health, United States [Internet]. 2024. [cited 25 December 2024]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/sources-definitions/joinpoint.htm. |

| 10. | Heart MY, Chase J, Elkins J, Altschul DB. Historical trauma among Indigenous Peoples of the Americas: concepts, research, and clinical considerations. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2011;43:282-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 307] [Cited by in RCA: 313] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Gone JP. Redressing First Nations historical trauma: theorizing mechanisms for indigenous culture as mental health treatment. Transcult Psychiatry. 2013;50:683-706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Risk for COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death by race/ethnicity [Internet]. 2021. [cited 30 December 2025]. Available from: https://archive.cdc.gov/www_cdc_gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html. |

| 13. | Matarazzo A, Hennekens CH, Dunn J, Benson K, Willett Y, Levine RS, Mejia MC, Kitsantas P. New Clinical and Public Health Challenges: Increasing Trends in United States Alcohol Related Mortality. Am J Med. 2025;138:477-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Weisner C, Schmidt L. Gender disparities in treatment for alcohol problems. JAMA. 1992;268:1872-1876. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Okafor CN, Plankey MW, Goodman-Meza D, Li M, Bautista KJ, Bolivar H, Phyllis TC, Brown TT, Shoptaw SJ. Association between self-reported marijuana use and incident diabetes in women and men with and at risk for HIV. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;209:107935. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lutfiyya MN, McCullough JE, Mitchell L, Dean LS, Lipsky MS. Adequacy of diabetes care for older U.S. rural adults: a cross-sectional population based study using 2009 BRFSS data. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Dugani SB, Wood-Wentz CM, Mielke MM, Bailey KR, Vella A. Assessment of Disparities in Diabetes Mortality in Adults in US Rural vs Nonrural Counties, 1999-2018. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e2232318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ekerdt DJ, De Labry LO, Glynn RJ, Davis RW. Change in drinking behaviors with retirement: findings from the normative aging study. J Stud Alcohol. 1989;50:347-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Adejumo OA, Ogunbiyi EO, Chen LY. Nurse-Led Evidence-Based Diabetes Prevention Study: An Innovative Risk Reduction Program for Clients With Substance Use Disorders. J Addict Nurs. 2024;35:203-215. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | Horigian VE, Schmidt RD, Duan R, Parras D, Chung-Bridges K, Batycki JN, Espinoza K, Taghioff P, Gonzalez S, Davis C, Feaster DJ. Untreated substance use disorder affects glycemic control: Results in patients with type 2 diabetes served within a network of community-based healthcare centers in Florida. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1122455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hochstatter KR, Nordeck C, Mitchell SG, Schwartz RP, Welsh C, Gryczynski J. Polysubstance use and post-discharge mortality risk among hospitalized patients with opioid use disorder. Prev Med Rep. 2023;36:102494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Terechin O, Johansen PM, Rosen AR, Morgan M, Fraenkel L. Mortality Rate Among Patients with Alcohol Use Disorder with Two or More Readmissions to the Hospital. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2023;13:90-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Wu LT, Ghitza UE, Batch BC, Pencina MJ, Rojas LF, Goldstein BA, Schibler T, Dunham AA, Rusincovitch S, Brady KT. Substance use and mental diagnoses among adults with and without type 2 diabetes: Results from electronic health records data. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2015;156:162-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Moore AA, Karno MP, Grella CE, Lin JC, Warda U, Liao DH, Hu P. Alcohol, tobacco, and nonmedical drug use in older U.S. Adults: data from the 2001/02 national epidemiologic survey of alcohol and related conditions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:2275-2281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Forthal S, Choi S, Yerneni R, Zhang Z, Siscovick D, Egorova N, Mijanovich T, Mayer V, Neighbors C. Substance Use Disorders and Diabetes Care: Lessons From New York Health Homes. Med Care. 2021;59:881-887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/