Published online Mar 20, 2026. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v16.i1.108611

Revised: May 30, 2025

Accepted: August 20, 2025

Published online: March 20, 2026

Processing time: 298 Days and 8.3 Hours

Red cell distribution width (RDW) measures the red blood cell size variation. Elevated RDW has been associated with various adverse health outcomes, in

To analyze current evidence on the prognostic significance of high RDW in patients with heart failure (HF).

A comprehensive literature search was conducted across multiple databases, including PubMed, EMBASE, and Google Scholar, up to May 2024. Studies were included if they investigated the relationship between RDW levels and outcomes in HF patients. Compared to those in the lowest quartile. The primary outcome was all-cause mortality. Compared to those in the lowest quartile. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic, we assessed the impact of individual studies on the overall estimate using a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis and publication bias was evaluated through a contour-enhanced funnel plot and Luis Furuya-Kana

Seven studies, including a total of 11460 HF patients, were analyzed. The par

This meta-analysis confirms that high RDW is a robust predictor of adverse outcomes in patients with HF, highlighting its potential utility as a simple, cost-effective biomarker for risk stratification. Future research should focus on elucidating the mechanisms underlying this association and exploring the potential benefits of RDW-guided therapeutic strategies in HF management.

Core Tip: Elevated red cell distribution width serves as a simple, cost-effective prognostic marker for adverse outcomes in heart failure (HF) patients, aiding risk stratification and highlighting the need to explore its mechanistic role and therapeutic potential in HF management.

- Citation: Senapati SG, Kothawala A, Ahluwalia V, Desai R. High red cell distribution width as a prognostic indicator in heart failure. World J Methodol 2026; 16(1): 108611

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v16/i1/108611.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v16.i1.108611

Heart failure (HF) is widely acknowledged as one of the most critical cardiovascular syndromes globally, characterized by a high incidence, prevalence, and mortality rate[1]. The condition manifests through various symptoms and signs, such as dyspnea and fatigue, which significantly compromise exercise tolerance. Other indicators include fluid retention, pulmonary and/or splanchnic congestion, ankle swelling, peripheral edema, elevated jugular venous pressure, and pulmonary crackles[2,3]. Effective management of HF patients depends on precise risk stratification to identify those at elevated risk of adverse outcomes, enabling early and tailored interventions. HF is classified based on left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) as follows: (1) HF with reduced ejection fraction (EF) (LVEF ≤ 40%); (2) HF with mid-range EF (LVEF: 41%-49%); and (3) HF with preserved EF (LVEF ≥ 50%)[2]. Tools for HF prognosis include laboratory tests, imaging studies, and clinical signs[4]. Various measures from transthoracic echocardiography, including EF, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), and cardiac troponin, have been investigated as biomarkers to assess treat

Red cell distribution width (RDW), a routine hematologic parameter, quantifies the variation in erythrocyte volume in circulation. Changes in RDW have been linked to outcomes in various patient populations, including those with cardiovascular diseases such as stable coronary artery disease, acute coronary syndromes, acute myocardial infarction, stroke, and HF[6]. Although numerous studies have examined the prognostic significance of RDW in HF, the findings have often been inconsistent. Consequently, meta-analysis, a statistical approach designed to synthesize the results of available studies has gained recognition as an effective methodology for drawing robust conclusions on this topic. Therefore, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the prognostic value of RDW in patients with HF.

Two authors independently searched the PubMed, EMBASE, and Google Scholar databases to identify eligible studies published up to May 17, 2024. The search terms for the PubMed search were: “heart failure” OR “cardiac failure” AND “RDW” OR “red cell distribution width” OR “erythrocyte indices”. A similar search strategy was used to search Embase. Manual searches were also performed by reviewing the references of the eligible studies and reviews on this topic.

Studies were included if they involved patients diagnosed with HF and reported RDW levels either as continuous variables or divided into quartiles. The comparison of interest was between patients in the highest RDW quartile (> 15.21%) and those in the lowest quartile (14.1%-15.20%). The meta-analysis divided RDW values into four quartiles, each representing 25% of the 11460 HF patients studied. The comparison of interest focused on the highest RDW quartile, comprising patients with RDW values above 15.21%, and the lowest quartile, which included patients with RDW values ranging from 14.1% to 15.20%. These four quartiles were created by ordering the RDW values from lowest to highest and splitting them into four equal groups based on patient count. The lowest value in the lowest quartile is explicitly 14.1%, marking the starting point of this range, while the highest quartile encompasses all values exceeding 15.21%. The primary outcome was all-cause mortality. Eligible studies included cohort studies, case-control studies, and randomized con

Two independent reviewers extracted data using a standardized collection form. Extracted information included study characteristics (author, publication year, country, study design, sample size, and follow-up duration), patient characteristics (mean age, gender distribution, HF classification, and comorbidities), RDW measurement methods (quartile cut-off values and units), and outcome measures [odds ratios (ORs) or hazard ratios (HRs) with 95%CI for all-cause mortality]. Any discrepancies in data extraction were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer.

A meta-analysis was conducted using a random-effects model to estimate the association between RDW levels and all-cause mortality. A χ2 test (Q-test) was also performed to evaluate statistical variability. Heterogeneity across studies was assessed using the I2 statistic, with values > 50% indicating substantial heterogeneity. To assess the robustness of the findings, a leave-one-out sensitivity analysis was conducted, where each study was systematically removed to examine its influence on the pooled estimate. The findings remained consistent, reinforcing the reliability of the results. Pu

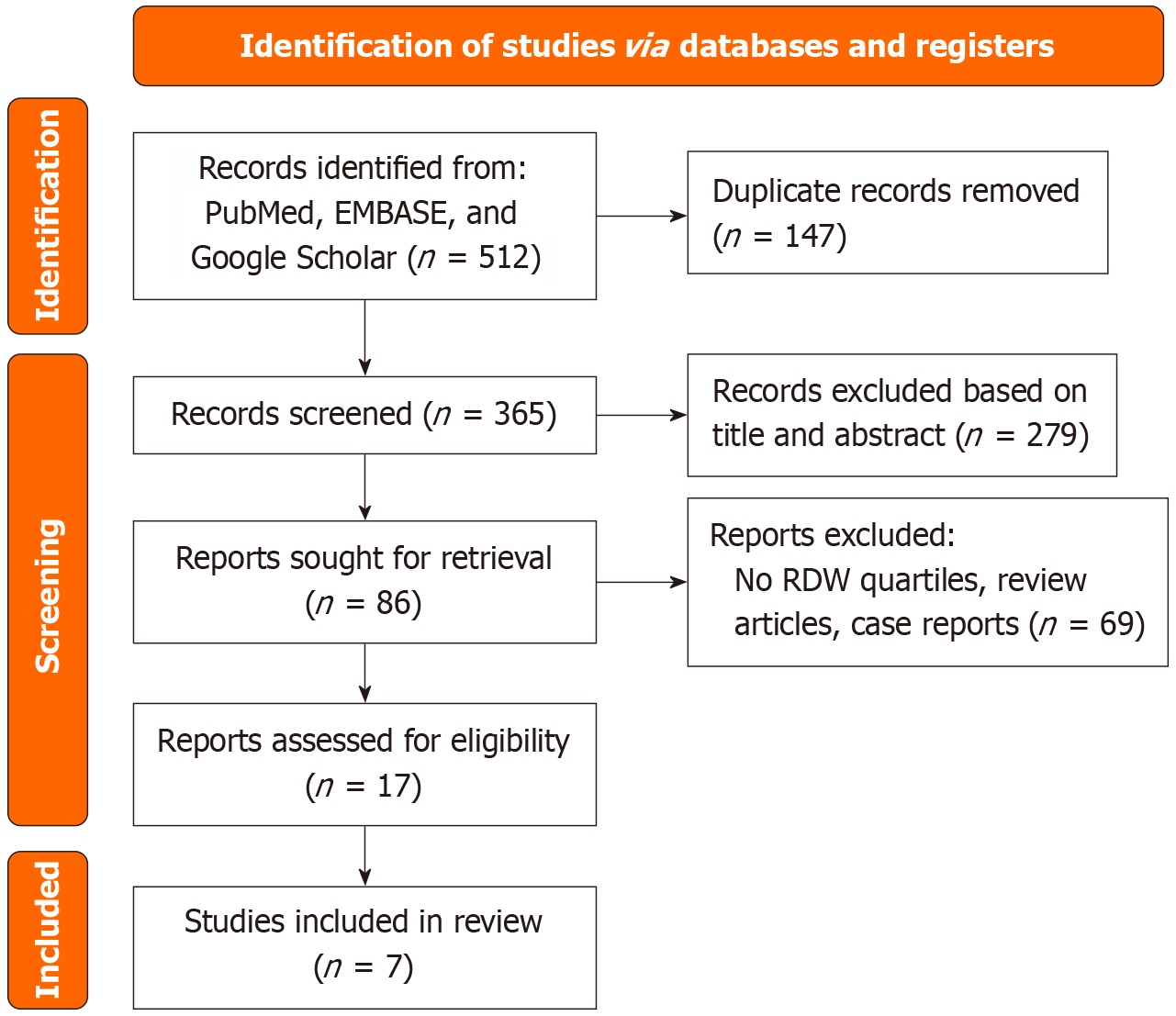

Following a comprehensive search of PubMed, EMBASE, and Google Scholar, 512 articles were identified. After removing 147 duplicates, 365 articles were screened. Of these, 279 were excluded based on title and abstract, leaving 86 for full-text review, with 7 studies ultimately included. The comprehensive details of our literature search and selection process can be found in the PRISMA flow chart (Figure 1).

This meta-analysis included seven studies comprising a total of 11460 HF patients. The participants were categorized into two groups based on their RDW levels: (1) The low quartile group (n = 6562); and (2) The high quartile group (n = 5098). The characteristics of the study populations are summarized in Table 1. The cohort represented a diverse patient population with a mean age of 78.9 years across all studies. The majority of participants were male (58.5%). The patients exhibited a significant prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors, including hypertension (62.0%) and diabetes (37.9%). The mean LVEF was reported at 42.7%, indicating an overall compromised cardiac function typical of HF patients. In terms of management, a notable percentage of patients were on beta-blockers (62.4%) and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers (67.9%), indicating adherence to pharmacological recommendations for HF treatment. Laboratory findings indicated an average estimated glomerular filtration rate of 66.1 mL/minute/1.73 m², which suggests moderate renal function across the cohort.

| Characteristic | Combined studies (n = 11460) | Low quartile (n = 6562) | High quartile (n = 5098) |

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Female sex (%) | 41.5 | 40.4 | 41.5 |

| Age (years) (mean) | 78.9 | 71.3 | 78.8 |

| Body mass index (kg/m²) (mean) | 29.0 | 30.1 | 28.9 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) (mean) | 142.0 | 138.0 | 142.0 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) (mean) | 83.3 | 83.0 | 83.3 |

| Heart rate (bpm) (mean) | 78.0 | 80.6 | 78.0 |

| NYHA I-II (%) | 64.6 | 49.4 | 64.6 |

| NYHA III-IV (%) | 35.2 | 50.5 | 35.2 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) (mean) | 42.7 | 41.5 | 42.7 |

| Previous myocardial infarction (%) | 41.5 | 37.0 | 41.5 |

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter (%) | 21.2 | 30.0 | 21.2 |

| Hypertension (%) | 62.0 | 57.0 | 62.0 |

| Diabetes (%) | 37.9 | 39.9 | 37.9 |

| Angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin II receptor blocker (%) | 67.9 | 66.2 | 67.9 |

| Beta-blocker (%) | 62.4 | 61.8 | 62.4 |

| Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (%) | 17.9 | 21.0 | 17.9 |

| Calcium channel blocker (%) | 10.4 | 11.7 | 10.4 |

| Statin (%) | 51.2 | 44.8 | 51.2 |

| Loop diuretics (%) | 68.8 | 79.4 | 68.8 |

| Baseline laboratory studies | |||

| White blood cell (cells/μL) (mean) | 7.7 | 7.6 | 7.7 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) (mean) | 12.0 | 11.5 | 12.0 |

| Mean corpuscular volume (fL) (mean) | 89.3 | 86.1 | 89.3 |

| Estimated glomerular filtration rate (mL/minute/1.73 m²) (mean) | 66.1 | 56.6 | 66.1 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) (mean) | 1.2 | 1.5 | 1.2 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) (mean) | 36.8 | 41.5 | 36.8 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) (mean) | 165.6 | 152.5 | 165.6 |

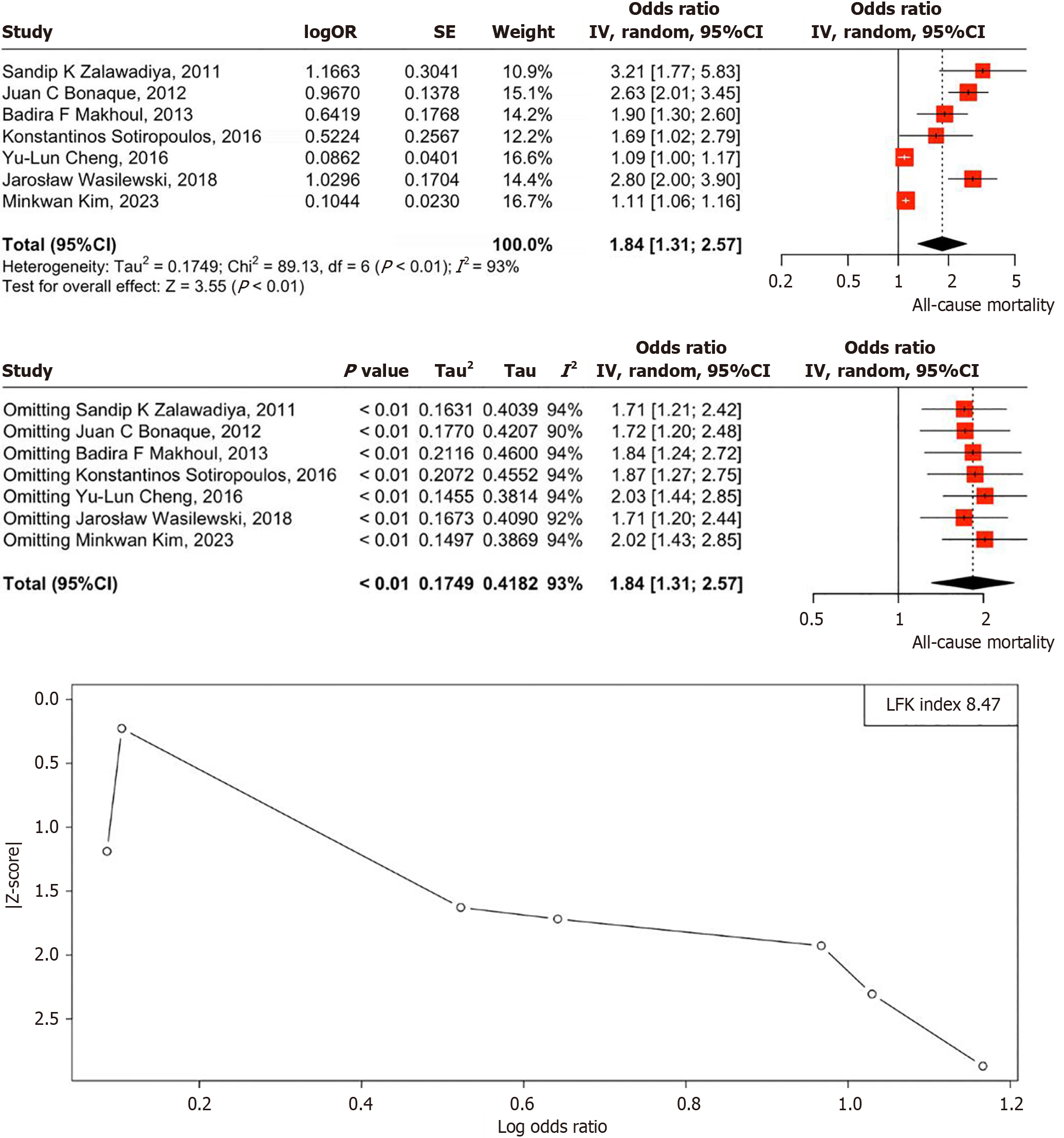

The OR analysis suggests a significant association between high RDW levels and increased all-cause mortality among HF patients. The pooled OR of 1.84 (95%CI: 1.31-2.57, P < 0.01) indicates that patients in the highest RDW quartile (> 15.21%) face a notably higher risk of mortality compared to those in the lowest quartile (RDW: 14.1%-15.20%). Heterogeneity across studies was assessed using the I2 statistic, with an observed I2 of 93% (P < 0.01) indicating substantial heterogeneity. The forest plot visually summarizes these results, but the LFK index of 8.47, indicating major asymmetry, suggests significant publication bias, implying that unpublished studies with negative or null findings may affect the reliability of these results. Despite this, RDW remains a promising prognostic biomarker for HF management, though caution is warranted due to potential bias (Figure 2)[5,7-12]. Quality of each study has been assessed and can be found in Table 2[5,7-12].

| Ref. | Year | Population (n) | RDW quartiles | Primary outcome | Follow-up duration | Newcastle-Ottawa Scale score (selection/comparability/outcome) | Notes on quality |

| Zalawadiya et al[7] | 2011 | 635 | Q1: < 14%, Q4: > 16.5% | All-cause mortality | 1.5 years | 3/1/2 (6/9) | Moderate quality. Clear cohort selection, but limited adjustment for confounders (e.g., only age and sex). Older publication may affect generalizability |

| Bonaque et al[8] | 2012 | 698 | Q1: Not specified, Q4: Not specified | Mortality | 2.5 years | 3/2/3 (8/9) | Good quality. Robust outcome assessment and follow-up, but RDW quartile definitions are unclear, limiting comparability |

| Makhoul et al[9] | 2013 | 614 | Q1: < 15.2%, Q4: > 15.3% | Clinical outcomes (heart failure hospitalization, mortality) | 1 year | 3/1/2 (6/9) | Moderate quality. Adequate selection and outcome reporting, but small sample size and limited confounder adjustment reduce robustness |

| Sotiropoulos et al[10] | 2016 | 402 | Q1: 12.2%-14.2%, Q4: 16.7%-32.1% | Mortality | 1 year | 3/1/2 (6/9) | Moderate quality. Small sample size limits statistical power. Clear RDW quartiles, but limited adjustment for confounders |

| Cheng et al[11] | 2016 | 978 | Q1: ≤ 14.3%, Q4: > 14.3% | Mortality | 30 months | 3/2/3 (8/9) | Good quality. Strong outcome assessment and longer follow-up, but focus on cardiorenal anemia syndrome may introduce confounding |

| Wasilewski et al[12] | 2018 | 1734 | Q1: ≤ 13.4%, Q4: > 14.6% | Mortality | 660 days (approximately 1.8 years) | 4/2/3 (9/9) | High quality. Large cohort, robust selection, and comprehensive confounder adjustment. Clear outcome reporting |

| Kim et al[5] | 2023 | 6399 | Q1: 12.7% ± 0.5%, Q4: 15.0% ± 1.9% | All-cause mortality | 3 months | 4/2/2 (8/9) | Good quality. Large sample size and clear selection, but short follow-up (3 months) limits long-term prognostic insights |

Our meta-analysis demonstrates that elevated RDW significantly increases all-cause mortality in HF patients. Patients in the highest RDW quartile had an 84% higher mortality risk (OR: 1.84, 95%CI: 1.31-2.57, P < 0.001) compared to those in the lowest quartile. This association remained consistent despite high heterogeneity (I2 = 93%), suggesting a strong prognostic value of RDW across diverse HF populations. Although publication bias was detected, trim-and-fill analysis yielded an adjusted OR of 1.72 (95%CI: 1.25-2.45), which remained statistically significant.

Several biological mechanisms may explain the observed relationship between RDW and HF outcomes. Increased RDW reflects greater variability in red blood cell size, which can result from underlying inflammation, oxidative stress, and impaired erythropoiesis. Chronic inflammation in HF leads to altered iron metabolism and reduced erythropoietin activity, contributing to ineffective red blood cell production. Oxidative stress further damages red blood cells, leading to increased turnover and variability in size. Additionally, endothelial dysfunction and microvascular impairment, both common in HF, may exacerbate erythropoietic disturbances, reinforcing the link between RDW and disease progression.

In recent years, multiple prospective cohort studies have explored the role of RDW in risk assessment for patients with acute HF. Notably, these studies consistently demonstrate a strong association between elevated RDW at admission and all-cause mortality[9,13,14]. Our meta-analysis confirms that elevated RDW is a strong predictor of all-cause mortality in HF patients, with those in the highest RDW quartile facing an 84% greater risk of death (OR: 1.84, 95%CI: 1.31-2.57, P < 0.001) compared to the lowest quartile.

Similarly, Huang et al[4] conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of 17 cohort studies involving 18288 patients with acute or chronic HF. The analysis found that both higher baseline RDW and increases in RDW during treatment were linked to worse prognosis, with each 1% rise in RDW at admission corresponding to a 10% higher risk of mortality (HR: 1.10, 95%CI: 1.07-1.13)[4]. However, the predictive value of RDW in these studies may have been influenced by unaccounted factors, as only one study adjusted for comorbidities, and none considered functional status.

These findings were confirmed by another comprehensive meta-analysis involving 41311 patients with HF from 17 studies, which reported that each 1% increase in RDW was associated with a 12% higher risk of death (HR: 1.12, 95%CI: 1.08-1.16). This association was slightly stronger in chronic HF (HR: 1.13, 95%CI: 1.08-1.18) compared to acute HF (HR: 1.09, 95%CI: 1.04-1.15), reinforcing RDW as a significant predictor of mortality across HF subtypes[15].

While some studies in our meta-analysis adjusted for key confounders such as anemia, renal dysfunction, and inflammation, others did not, raising the possibility of residual confounding. However, evidence from Melchio et al[14] suggests that RDW provides prognostic value beyond these conventional risk factors in patients hospitalized for acute HF (AHF). Even after adjusting for variables such as age, HF etiology, anemia, renal function, NT-proBNP, and comorbidities, higher RDW remained independently associated with increased mortality (HR: 1.73, P = 0.003). This finding reinforces the notion that RDW is not merely a secondary marker of disease severity but may capture underlying pathophysiological processes not fully accounted for by traditional biomarkers. Consequently, RDW could serve as an independent risk stratification tool in AHF, warranting further investigation into its therapeutic implications.

Our study showed adjustments for anemia slightly weakened the association, indicating that underlying hematologic abnormalities may partly mediate RDW’s effects. However, findings from Núñez et al[16] demonstrated that RDW remains a strong predictor of mortality regardless of anemia status. In their study of 1702 HF patients followed for a median of 18 months, both baseline and longitudinally updated RDW were independently associated with all-cause mortality in anemic (HR: 1.04-1.08) and non-anemic (HR: 1.11-1.31). The stronger association observed with repeated RDW measurements highlights its prognostic stability over time.

Higher RDW thresholds enhance its prognostic value in HF. In fact, RDW is not just a general prognostic marker but its impact on mortality becomes more pronounced at higher levels, potentially making it a more reliable risk stratification tool in HF management. Our meta-analysis demonstrated that stricter RDW thresholds (> 15.5%) were associated with a stronger correlation between RDW and mortality. Supporting this trend, Ferreira et al[17] found that an admission RDW > 15% in patients with acute decompensated HF was independently associated with a 29% higher risk of hospitalization for acute HF or 180-day cardiovascular death (OR: 1.29, 95%CI: 0.71-2.33).

While most studies have focused on baseline RDW as a predictor of all-cause mortality, recent evidence suggests that longitudinal RDW trends provide additional prognostic value. In a study of 1702 patients discharged after an AHF admission, rising RDW values over time were associated with an increased risk of both mortality and incident anemia, with a more pronounced effect in non-anemic patients (HR: 1.31-1.48) compared to anemic patients (HR: 1.08-1.12)[16]. This points to the fact that RDW is not merely a static biomarker but a dynamic indicator of disease progression, possibly reflecting worsening inflammation, oxidative stress, and bone marrow dysfunction.

RDW is an easily accessible and cost-effective biomarker that could be integrated into routine clinical practice for risk stratification in HF patients. Unlike more complex and costly biomarkers, such as NT-proBNP or high-sensitivity troponins, RDW is included in standard complete blood counts, making it widely available. Current evidence strongly supports the prognostic value of RDW, demonstrating its ability to predict adverse outcomes such as cardiovascular and all-cause mortality, hospitalization due to acute decompensation, and cardiac dysfunction in patients with HF. Moreover, RDW has been identified as an independent predictor of incident HF in individuals without the condition at baseline[4,15,18]. Given its strong association with mortality risk, RDW may help clinicians identify high-risk patients who require closer monitoring, earlier intervention, or more aggressive management strategies.

Additionally, tracking RDW changes over time-whether during hospitalization or shortly thereafter-may offer even greater predictive accuracy for adverse outcomes in patients with chronic, acute, and acutely decompensated HF[9,16,17]. One key advantage of longitudinal RDW assessment is its consistency across different hematology analyzers. Evaluating RDW trends, either as absolute differences or ratio-based changes from baseline, could help mitigate the issue of measurement variability, which remains a challenge in defining a universally accepted prognostic threshold[19]. Notably, two studies that combined RDW values at admission with subsequent variations during follow-up demonstrated superior predictive performance compared to using either measure alone for forecasting adverse events in HF patients[16,20].

In summary, serial RDW measurements-particularly when baseline values are integrated with subsequent changes during hospitalization or outpatient care-may serve as a cost-effective and reliable approach for risk stratification and prognosis assessment in HF patients.

Several limitations of this meta-analysis should be acknowledged. First, the included studies were predominantly observational, limiting the ability to establish a causal relationship between RDW and HF outcomes. Second, substantial heterogeneity was observed across studies, likely due to variations in patient populations, RDW thresholds, and follow-up durations. Notably, RDW categorization differed among studies—some used quartiles (e.g., Zalawadiya et al[7]), while others applied binary cutoffs (e.g., Cheng et al[11], Szlacheta et al[21])-which may have influenced effect size estimates.

Additionally, the inclusion of both acute and chronic HF populations introduced variability in disease severity and treatment responses. Follow-up durations ranged from 3 months to over 3 years, potentially affecting the observed associations with mortality risk. While some studies adjusted for key confounders such as anemia, renal dysfunction, and inflammation, others did not, leading to the possibility of residual confounding. Furthermore, the inclusion of both retrospective and prospective studies contributed to methodological variability. Lastly, potential publication bias cannot be ruled out, as smaller studies with negative findings may be underrepresented, possibly leading to a slight overestimation of the true effect size.

Future research should further explore the complex interplay between HF, hematopoiesis, and RDW. HF is linked to nutritional deficiencies and oxidative stress, both of which can disrupt red blood cell production. Additionally, renal dysfunction in HF contributes to anemia and anisocytosis, while older age-an independent risk factor for HF-is also associated with altered red cell morphology due to metabolic changes. To establish a clearer understanding of RDW’s prognostic significance, large-scale prospective studies that rigorously control for confounding factors are needed.

Iron deficiency (ID), a well-recognized contributor to anisocytosis, is prevalent in both chronic and acute HF, with reported rates as high as 58%-83%[22]. Notably, ID correction with intravenous ferric carboxy maltose has been shown to reduce RDW in a sub-analysis of the FAIR-HF trial. However, whether treating ID during acute HF hospitalizations can improve long-term outcomes remains unclear. Ongoing trials, such as AFFIRM-AHF (NCT02937454), aim to evaluate whether ID correction can lower mortality and readmission rates, providing crucial insights into potential therapeutic strategies targeting RDW.

Further studies are needed to determine whether RDW is merely a marker of disease severity or a modifiable risk factor in HF progression. If validated, RDW-targeted therapies could emerge as a novel approach in HF management. Future research should also assess whether stabilizing RDW fluctuations could improve short-term and long-term HF outcomes, potentially refining risk stratification and treatment strategies.

Our meta-analysis confirms that elevated RDW significantly predicts increased all-cause mortality in HF patients, with an 84% higher risk in the highest RDW quartile. This association persists despite high heterogeneity and slight attenuation by anemia adjustments. RDW's prognostic value is supported by subgroup analyses and previous studies, reflecting underlying inflammation and oxidative stress in HF. Clinically, RDW's accessibility makes it valuable for risk stratification. Future research should explore RDW's causality and potential as a modifiable risk factor, possibly guiding novel HF management strategies.

| 1. | Bui AL, Horwich TB, Fonarow GC. Epidemiology and risk profile of heart failure. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;8:30-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1550] [Cited by in RCA: 1445] [Article Influence: 96.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Anker SD, Bueno H, Cleland JGF, Coats AJS, Falk V, González-Juanatey JR, Harjola VP, Jankowska EA, Jessup M, Linde C, Nihoyannopoulos P, Parissis JT, Pieske B, Riley JP, Rosano GMC, Ruilope LM, Ruschitzka F, Rutten FH, van der Meer P; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2129-2200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10348] [Cited by in RCA: 9585] [Article Influence: 958.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 3. | Writing Committee Members; Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE Jr, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL, Johnson MR, Kasper EK, Levy WC, Masoudi FA, McBride PE, McMurray JJ, Mitchell JE, Peterson PN, Riegel B, Sam F, Stevenson LW, Tang WH, Tsai EJ, Wilkoff BL; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:e240-e327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1041] [Cited by in RCA: 1590] [Article Influence: 122.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Huang YL, Hu ZD, Liu SJ, Sun Y, Qin Q, Qin BD, Zhang WW, Zhang JR, Zhong RQ, Deng AM. Prognostic value of red blood cell distribution width for patients with heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. PLoS One. 2014;9:e104861. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Kim M, Lee CJ, Kang HJ, Son NH, Bae S, Seo J, Oh J, Rim SJ, Jung IH, Choi EY, Kang SM. Red cell distribution width as a prognosticator in patients with heart failure. ESC Heart Fail. 2023;10:834-845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Xanthopoulos A, Giamouzis G, Dimos A, Skoularigki E, Starling RC, Skoularigis J, Triposkiadis F. Red Blood Cell Distribution Width in Heart Failure: Pathophysiology, Prognostic Role, Controversies and Dilemmas. J Clin Med. 2022;11:1951. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zalawadiya SK, Zmily H, Farah J, Daifallah S, Ali O, Ghali JK. Red cell distribution width and mortality in predominantly African-American population with decompensated heart failure. J Card Fail. 2011;17:292-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bonaque JC, Pascual-Figal DA, Manzano-Fernández S, González-Cánovas C, Vidal A, Muñoz-Esparza C, Garrido IP, Pastor-Pérez F, Valdés M. Red blood cell distribution width adds prognostic value for outpatients with chronic heart failure. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2012;65:606-612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Makhoul BF, Khourieh A, Kaplan M, Bahouth F, Aronson D, Azzam ZS. Relation between changes in red cell distribution width and clinical outcomes in acute decompensated heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:1412-1416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sotiropoulos K, Yerly P, Monney P, Garnier A, Regamey J, Hugli O, Martin D, Metrich M, Antonietti JP, Hullin R. Red cell distribution width and mortality in acute heart failure patients with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. ESC Heart Fail. 2016;3:198-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cheng YL, Cheng HM, Huang WM, Lu DY, Hsu PF, Guo CY, Yu WC, Chen CH, Sung SH. Red Cell Distribution Width and the Risk of Mortality in Patients With Acute Heart Failure With or Without Cardiorenal Anemia Syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2016;117:399-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wasilewski J, Pyka Ł, Hawranek M, Tajstra M, Skrzypek M, Wasiak M, Suliga K, Bujak K, Gąsior M. Prognostic value of red blood cell distribution width in patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction: Insights from the COMMIT-HF registry. Cardiol J. 2018;25:377-385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Uemura Y, Shibata R, Takemoto K, Uchikawa T, Koyasu M, Watanabe H, Mitsuda T, Miura A, Imai R, Watarai M, Murohara T. Elevation of red blood cell distribution width during hospitalization predicts mortality in patients with acute decompensated heart failure. J Cardiol. 2016;67:268-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Melchio R, Rinaldi G, Testa E, Giraudo A, Serraino C, Bracco C, Spadafora L, Falcetta A, Leccardi S, Silvestri A, Fenoglio L. Red cell distribution width predicts mid-term prognosis in patients hospitalized with acute heart failure: the RDW in Acute Heart Failure (RE-AHF) study. Intern Emerg Med. 2019;14:239-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Shao Q, Li L, Li G, Liu T. Prognostic value of red blood cell distribution width in heart failure patients: a meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2015;179:495-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Núñez J, Núñez E, Rizopoulos D, Miñana G, Bodí V, Bondanza L, Husser O, Merlos P, Santas E, Pascual-Figal D, Chorro FJ, Sanchis J. Red blood cell distribution width is longitudinally associated with mortality and anemia in heart failure patients. Circ J. 2014;78:410-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ferreira JP, Girerd N, Arrigo M, Medeiros PB, Ricardo MB, Almeida T, Rola A, Tolpannen H, Laribi S, Gayat E, Mebazaa A, Mueller C, Zannad F, Rossignol P, Aragão I. Enlarging Red Blood Cell Distribution Width During Hospitalization Identifies a Very High-Risk Subset of Acutely Decompensated Heart Failure Patients and Adds Valuable Prognostic Information on Top of Hemoconcentration. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e3307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hou H, Sun T, Li C, Li Y, Guo Z, Wang W, Li D. An overall and dose-response meta-analysis of red blood cell distribution width and CVD outcomes. Sci Rep. 2017;7:43420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lippi G, Pavesi F, Bardi M, Pipitone S. Lack of harmonization of red blood cell distribution width (RDW). Evaluation of four hematological analyzers. Clin Biochem. 2014;47:1100-1103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Muhlestein JB, Lappe DL, Anderson JL, Muhlestein JB, Budge D, May HT, Bennett ST, Bair TL, Horne BD. Both initial red cell distribution width (RDW) and change in RDW during heart failure hospitalization are associated with length of hospital stay and 30-day outcomes. Int J Lab Hematol. 2016;38:328-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Szlacheta P, Malinowska-Borowska J, Nowak JU, Buczkowska M, Kulik A, Mroczek A, Duda S, Ostręga W, Niedziela JT, Skrzypek M, Gąsior M, Rozentryt P. Long-term prognostic scores may underestimate the risk of death in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction in whom red cell distribution width is elevated. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2023;133:16494. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | van Veldhuisen DJ, Anker SD, Ponikowski P, Macdougall IC. Anemia and iron deficiency in heart failure: mechanisms and therapeutic approaches. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;8:485-493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/