Published online Mar 20, 2026. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v16.i1.107908

Revised: May 20, 2025

Accepted: August 4, 2025

Published online: March 20, 2026

Processing time: 316 Days and 13.4 Hours

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common functional bowel disorder characterized by abdominal pain and altered bowel habits, with types classified based on stool patterns: (1) Diarrhea-predominant IBS (IBS-D); (2) IBS with constipation (IBS-C); and (3) Mixed IBS. This condition affects approximately 10% of adults globally and is challenging to treat due to the lack of definitive structural or bio

To review existing literature to evaluate Mirtazapine’s effectiveness in treating IBS, particularly in older patients.

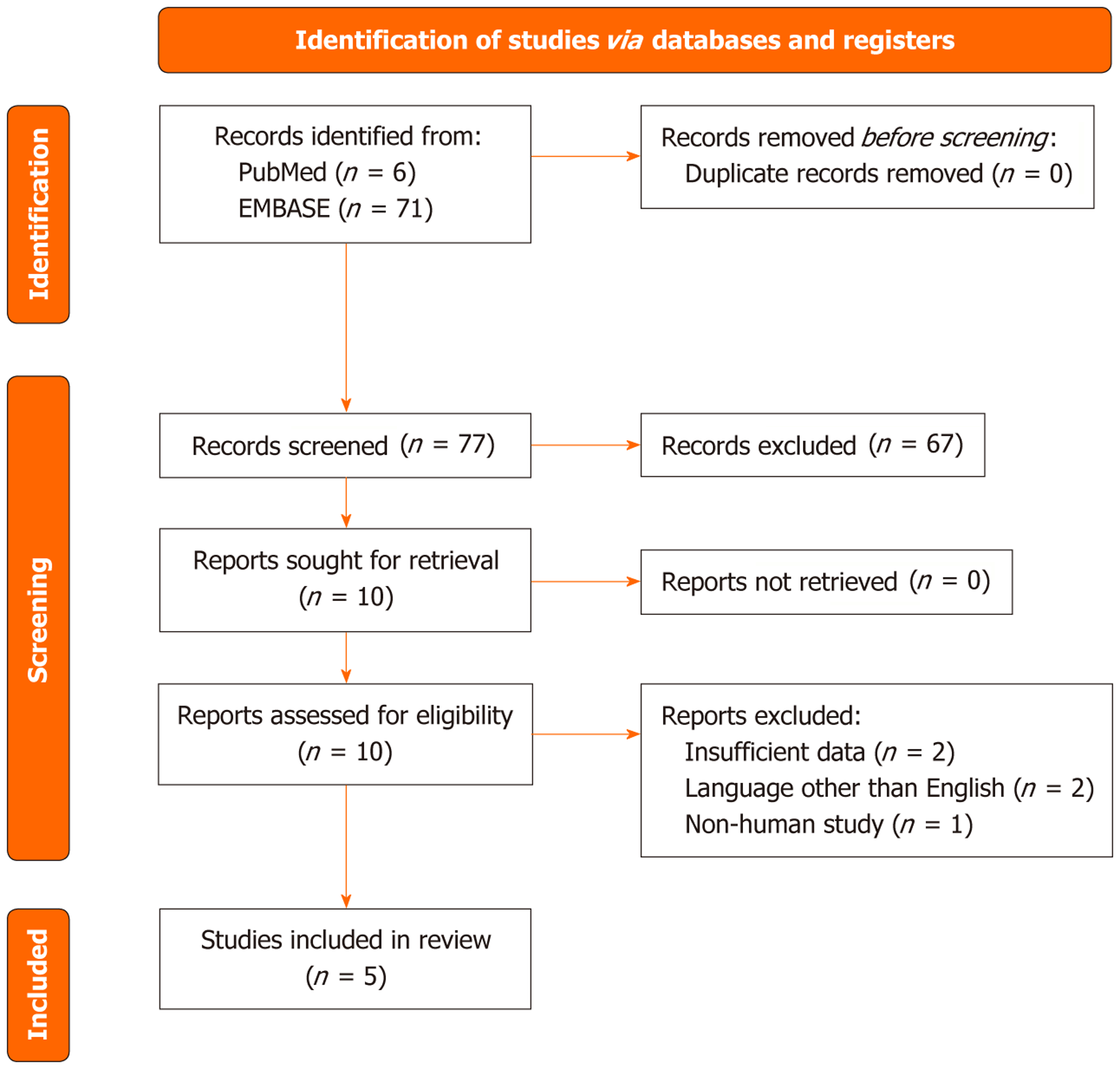

This review as registered in the PROSPERO database (CRD420251022721) and followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines. A systematic review was conducted between February 2024 and March 2024, searching PubMed, EMBASE, and BMJ Case Reports from database inception to present. We included English-language randomized controlled trials (RCTs), prospective clinical studies, and case reports of adult IBS-D or IBS-C patients treated with Mirtazapine, reporting on symptom resolution, abdominal pain, insomnia, or related outcomes. Data extraction covered study design, sam

Of 77 identified references, five publications met inclusion criteria: (1) Three case reports; (2) One double-blind RCT (n = 67; Mirtazapine vs placebo); and (3) One prospective study (n = 116 with comorbid depression, 50 on Mirtazapine). The RCT demonstrated significant reductions in IBS symptoms severity score, diary-based symptoms (abdominal pain, urgency, frequency; all significant except bloating), and improved QoL and anxiety scores. Case reports (patients aged 35–66 years) reported normalization of stool frequency, weight gain, and relief of anxiety/depressive symptoms. The prospective study found baseline sleep disturbance correlated with improvements in pain and diarrhea.

Although evidence is limited, current data indicate Mirtazapine improves IBS-related symptoms and associated mental health issues, with rapid onset and good tolerability. The small number of studies and absence of large-scale RCTs warrant cautious interpretation. Further RCTs are essential to confirm Mirtazapine’s role in IBS trea

Core Tip: This study highlights the potential of mirtazapine in treating refractory irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), particularly diarrhea-predominant IBS with comorbid depression. By integrating a systematic review with a detailed case report, our findings demonstrate that mirtazapine, combined with Rifaximin, a low fermentable oligosaccharide, disaccharide, monosaccharide, and polyol diet, and probiotics, significantly improves patient outcomes. This work emphasizes the importance of thorough diagnostic evaluation in IBS and supports further randomized controlled trials to confirm mirtazapine's efficacy.

- Citation: Prodan R, Soldera J. Mirtazapine for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review. World J Methodol 2026; 16(1): 107908

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v16/i1/107908.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v16.i1.107908

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a functional bowel disorder presenting as chronic abdominal pain associated with bowel habit changes, such as diarrhea or constipation, often classified into subtypes [diarrhea-predominant IBS (IBS-D), IBS with constipation (IBS-C), mixed IBS] depending on stool patterns. IBS diagnosis is clinical, with limited testing to rule out other conditions like coeliac disease or inflammatory bowel disease[1,2]. Despite being highly prevalent, with an estimated 5%-20% of the population affected, many cases remain undiagnosed[3,4]. A recent large-scale United States study found that nearly half of individuals meeting IBS criteria had not sought medical care for their symptoms in the past year, highlighting a significant gap in diagnosis and management[5]. Additionally, a 2023 meta-analysis encom

Historically, IBS was considered to lack structural or biochemical changes and its treatment focused on symptom management, with limited long-term efficacy. Recent research suggests potential mechanisms underlying IBS, including altered sensory processing, anxiety, and depression, affecting 75% of patients and targeted with antidepressants; post-infectious and post-inflammatory changes, impacting 10%-30% of patients; bile acid malabsorption in about 20% of IBS-D cases; visceral hyperalgesia, accounting for 30%-40% of symptoms, treatable with psychotropic drugs; and mutations in SCN5A relevant to IBS-C, with Mexiletine as a possible therapy[2].

Although not considered life-threatening, IBS significantly impacts quality of life (QoL)—limiting daily activities, impairing work productivity, and contributing to social withdrawal, sleep disturbances, and emotional distress. Further investigation into its mechanisms could lead to more effective, targeted treatments, as there is no diagnostic gold stan

A thorough patient history, including medical, surgical, psychosocial, and lifestyle factors, is essential for assessing recurrent abdominal pain and altered bowel habits[7]. Physical examination is necessary, and any identified alarm features such as onset post-50, rectal bleeding, weight loss, or nocturnal diarrhea should lead to specific diagnostic tests[7].

In the absence of alarm features, recommended screenings include oral lactose tolerance test, C-reactive protein, fecal calprotectin, coeliac serology, and age-appropriate fit tests. Additional tests or a colonoscopy for patients under 40 are generally unwarranted[7]. Diagnosis then relies on Rome IV criteria, defining IBS as recurrent abdominal pain associated with defecation changes, altered stool frequency, or appearance, occurring at least weekly for three months[7].

Without definitive tests for IBS, effective clinician-patient communication on IBS’s visceral hypersensitivity and associated symptoms aids in acceptance of treatments like neuromodulators and behavioral therapy, while educating patients on factors like left colonic motility helps explain symptoms and treatment timing[7-9].

First-line treatments for IBS emphasize non-pharmacologic strategies such as regular exercise, dietary modifications—including a low fermentable oligosaccharide, disaccharide, monosaccharide, and polyol (FODMAP) diet—and the use of Ispaghula husk and probiotics, which are generally well-tolerated and accessible but may not provide adequate relief for all patients. Pharmacologic agents like Loperamide for IBS-D, antispasmodics, peppermint oil, and polyethylene glycol for IBS-C can offer symptomatic improvement, though their efficacy may be limited in patients with more complex or persistent symptoms[1]. When these approaches fail to achieve satisfactory control, second-line treatments are con

Refractory IBS remains challenging to manage, especially with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) and tricyclics’ side effects. Mirtazapine, as shown in a Cochrane review, may offer benefits with fewer adverse effects[3]. Late life depression, common in the elderly, is also linked to gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms[12].

Antidepressants are essential in IBS treatment, with tricyclics for IBS-D and SSRIs for IBS-C, though these drugs have significant side effects, including sexual dysfunction and nervousness. Tricyclics like Amitriptyline increase serotonin and norepinephrine levels, though they cause anticholinergic side effects (dry mouth, drowsiness), impacting elderly patients’ QoL by exacerbating fall risk and urinary issues[13].

Citalopram, a commonly used SSRI, poses bleeding risks with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or Warfarin, and its sexual side effects make it challenging for young, active IBS patients[14]. Other SSRIs—Sertraline, Fluoxetine, and Paroxetine—share similar side effect profiles.

Duloxetine, a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) commonly prescribed for chronic pain and de

In contrast, Mirtazapine exerts dual noradrenergic and serotonergic effects by antagonizing central alpha 2-adrenergic receptors and blocking 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptors, resulting in enhanced norepinephrine and serotonin release. Metabolized primarily by cytochrome P450 enzymes and excreted in urine, Mirtazapine has a rapid onset of action and a favorable side effect profile. Notably, it offers sedative and appetite-stimulating benefits without the sexual dysfunction associated with SSRIs and SNRIs[16,17]. These characteristics make it an attractive therapeutic candidate for IBS patients with comorbid insomnia, appetite loss, or SSRI intolerance—highlighting the rationale for exploring its role in functional GI disorders.

IBS treatment follows guideline-recommended steps: (1) First-line includes lifestyle and dietary changes, exercise, low-FODMAP diets, and medications like Loperamide, antispasmodics, and laxatives; and (2) Second-line options are antidepressants, Eluxadoline for IBS-D, and Linaclotide or Lubiprostone for IBS-C[1]. Psychological therapies, including CBT and gut-directed hypnotherapy, are recommended if symptoms persist beyond 12 months of pharmacotherapy[1].

The RESET model emphasizes multidisciplinary care for difficult IBS cases, focusing on patient-provider com

For mild IBS, treatment focuses on education, reassurance, dietary changes, and over the counter remedies. Moderate cases may require prescription medication and follow-up, while severe cases often benefit from gut-brain axis therapies, including neuromodulators and CBT, along with lifestyle adjustments[5].

Key frameworks support IBS management: The biopsychosocial model and the multidimensional clinical profile (MDCP), which personalize treatment based on the patient's symptom profile, psychological status, and physiological markers. MDCP uses five categories: (1) Rome diagnosis; (2) Clinical modifiers (e.g., IBS-C with depression); (3) Life impact; (4) Psychosocial factors (e.g., mental health history); and (5) Physiological markers (e.g., SeHcat for IBS-D bile acid issues)[5].

In severe cases: (1) IBS-D with sleep issues may benefit from a tricyclic like Amytriptilline for pain, sleep, and diarrhea relief; (2) Severe IBS-C with pain may respond to duloxetine, enhancing norepinephrine and serotonin; and (3) Stress-induced IBS symptoms may improve with CBT, alongside dietary and pharmacologic strategies for GI symptoms[5].

While the focus is on older adults, it is noteworthy that adolescents also experience IBS, often accompanied by sig

The present study aims to review existing literature on the use of Mirtazapine as a treatment option for IBS, specifically assessing its efficacy and potential benefits for the elderly population diagnosed with this condition.

The review protocol has been registered with the PROSPERO database number CRD420251022721, and the methodology will adhere to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines[20]. The systematic review intends to synthesize all available evidence on Mirtazapine's efficacy in IBS treatment.

The inclusion criteria prioritized clinical studies, specifically focusing on randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and prospective clinical studies, while also including relevant case reports. The intervention to be reviewed is Mirtazapine treatment in adult patients diagnosed with IBS. Studies were included if they reported on the effects of Mirtazapine on IBS symptoms, abdominal pain, or any other relevant outcomes. To ensure comprehensive coverage of relevant literature, we also utilized the Reference Citation Analysis database, an artificial intelligence-powered multidisciplinary citation analysis platform, to identify high-impact studies and recent publications on the use of Mirtazapine in IBS. This enhanced the robustness of our search strategy and minimized the risk of omitting pertinent evidence.

For our systematic review on the use of Mirtazapine for IBS, we conducted a literature search across PubMed, EMBASE, and BMJ Case Reports (Figure 1). The search was conducted from the inception of each database until the present, between February and March 2024. The language was restricted to English, and the reference lists of the retrieved studies were subjected to a manual search. The search command used was: ("mirtazapina" OR "mirtazapine" OR "tetracyclic antidepressant" OR "remeron") AND ("irritable bowel syndrome" OR "IBS" OR "IBS-D" OR "IBS-C" OR "visceral hypersensitivity" OR "visceral sensitivity").

Our literature search strategy revolved around the focused question: What is the evidence available for Mirtazapine in the treatment of IBS? We included patients diagnosed with IBS-D or IBS-C, aged 18 years or older. The inclusion criteria prioritized clinical studies, specifically focusing on RCTs and prospective clinical studies, while also selecting all available case reports.

The assessment of Mirtazapine's efficacy was centered on achieving the resolution of IBS symptoms, as per the Rome criteria for IBS. Additionally, we considered specific demographic factors, with particular emphasis on age groups. In defining the elderly cohort, we considered patients aged 65 years and older. Language restrictions were applied, requiring articles to be in English. Importantly, there were no exclusions based on publication date to ensure a comprehensive review of the available literature.

The intervention reviewed is Mirtazapine treatment in adult patients diagnosed with IBS. Studies were included if they reported on the effects of Mirtazapine on IBS symptoms, insomnia, abdominal pain, or other relevant outcomes. Both case series and RCTs were considered.

We included all studies/case reports involving adult patients with a diagnosis of IBS treated with Mirtazapine. We stratified the studies into groups based on the outcomes measured, such as imp

Comparators may have included placebo, no treatment, or standard care. Inclusion criteria for comparators enc

Studies were selected for inclusion based on predefined criteria. Data were extracted on study design, population characteristics, intervention details, outcomes measured, and results. Data fields extracted included author, year, study design, sample size, dosage of Mirtazapine, duration of treatment, and outcomes.

Due to significant heterogeneity and a paucity of studies reporting comparable outcomes, meta-analysis was not feasible. Therefore, we performed a systematic review.

The literature search was conducted on EMBASE, PubMed, and BMJ Case Reports. Using the PRISMA search strategy for systematic review, we initially identified 6 references on PubMed and 71 references on EMBASE. After screening the titles, 3 references were included from PubMed and 7 references were included from EMBASE. Following a review of the abstracts, only 3 references from PubMed and 5 references from EMBASE were included in the final analysis. The 3 included references from PubMed overlapped with the included records from EMBASE.

Ultimately, only 5 publications relevant to our review were identified: (1) Three case reports; (2) One randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study assessing the efficacy of mirtazapine for treating diarrhoea-predominant IBS; and (3) A prospective study on adult patients meeting Rome III criteria for IBS-D with comorbid depression who were treated with various neuromodulators, including mirtazapine (Table 1)[9,21-24].

| Ref. | Patients (n) | Intervention | Comparison | Study design | Outcomes | Results |

| Akama et al[9], 2018, Japan | Case report: 52-year-old female (1) | Mirtazapine, started 15 mg/day, increased to 30 mg/day after 2 weeks | Not applicable | Case report | IBS–D (diarrhoea–stool frequency, Abdo pain) and adjustment disorder symptoms (anxiety, irritability, depressed mood- Hamilton scale for depression HAM-D and for anxiety HAM-A monitored) | After 2 months of treatment, good response in: Stool frequency reduced from > 10×/day to 3×/day or less, improvement in abdominal pain, diarrhoea, reduction in HAM-D (from 22 points to 5 points) and HAM-A (from 22 points to 11 points) |

| Khalilian et al[23], 2021, Iran | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, included 67 patients meeting Rome IV criteria for IBS-D: 34 randomized to Mirtazapine group, 33 to placebo (67) | Mirtazapine 15 mg/day for the first week, increased from the second week to 30 mg/day for another 7 weeks | Placebo was used for comparison | Randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled | Outcomes included: Changes in the total IBS symptoms severity score, IBS-QoL and changes in the diary-based symptoms–pain, urgency, bloating, stool frequency and consistency; also, the number of days/weeks with pain/urgency/diarrhoea/bloating during first week of treatment and during last week of treatment | Mirtazapine was shown to be more efficacious in reducing the severity of the IBS symptoms (P = 0002) and all diary-derived symptoms except for bloating showed significant improvement in the treatment arm compared to placebo. QoL was improved significantly (P = 004) and so were anxiety symptoms (P = 005) with Mirtazapine |

| Spiegel and Kolb[21], 2011, United States | Case report: 66 years old female (1) | Mirtazapine | Not applicable | Case report | IBS–mixed type symptoms, worsened by panic attacks | Mirtazapine has resulted in decreasing in diarrhoea and constipation and psychopathological symptoms |

| Thomas[22], 2000, United States | Case report: 35 years old female (1) | Mirtazapine started at 7.5 mg/day, increased every 2 weeks until a max dose of 30 mg/day | Not applicable | Case report | Abdominal cramping, bloating, constipation and weight loss and repeated hospital visits and work absenteeism | Significant improvement noted at 12 weeks, with normal bowel movement, a marked decrease in all the gastrointestinal symptoms and gained back the lost weight. No missed workdays, no hospital visits |

| Lu et al[24], 2020, China | Prospective study: Adult patients who met Rome III criteria for IBS-D (using IBS specific symptoms questionnaire) and comorbid depression (using Hamilton Depression rating scale HAM-D: 410 patients recruited) | 116 patients were given neuromodulators, 97 patients completed the follow up. 50 patients received Mirtazapine (15-45 mg/day), 52 patients received Paroxetine, 17 received Flupentixol/Melitracen, the rest received Sertraline, Escitalopram, Venlafaxine and Fluoxetine. Mean treatment was 5 months | Not applicable | Prospective study–unable to describe further | Intestinal symptoms assessed using IBS symptoms specific questionnaires and psychological states using HAM-D scale | The baseline sleep disturbances score positively correlated with improvements in abdominal pain/discomfort and diarrhoea after mirtazapine therapy (r = 0.352, P = 0.026; r = 0.356, P = 0.024) |

The first case report from 2018 discusses a 52-year-old Japanese female patient with IBS-D, experiencing a stool frequency of around 10 times per day, which caused anxiety about leaving her house. Despite no prior mental health issues, she had recently been diagnosed with ovarian cancer and referred for a preoperative psychiatry consultation due to depressed mood, insomnia, and anxiety. Diagnosed with adjustment disorder, she scored 22 on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) and 28 on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (HAM-A). Initial treatments were ineffective; however, after initiating mirtazapine at 15 mg, increased to 30 mg after 2 weeks, her stool frequency improved to 3 times per day, and both anxiety and depressive symptoms significantly reduced (HAM-D score decreased to 5, HAM-A score decreased to 11). Consequently, her QoL improved, enabling her to perform housework and leave home[9].

The second case report from 2011 involves a 66-year-old woman in the United States with a one-year history of mixed-type IBS worsened by panic attacks, alongside panic disorder and major depression[21]. Prior to Mirtazapine, she had trialed several SSRIs—which exacerbated her IBS symptoms—and was taking up to 3 mg lorazepam three times daily for anxiety without relief of GI symptoms. During a hospitalization for pneumonia (when antibiotics further aggravated her diarrhea and she awoke nightly with 4–5 bowel movements despite negative Clostridium difficile tests), her body mass index (BMI) was 16.5 kg/m² and her Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale scores indicated severe anxiety and mild depression. Mirtazapine was initiated at 30 mg once daily at bedtime while her lorazepam dose was reduced to 2 mg three times daily; by the next morning she slept through the night without diarrhea, and within three days she had no bloating or abdominal pain and had begun alternating normal bowel movements. At four-week follow-up, she reported only one episode of diarrhea after a known dietary trigger, no further panic attacks, and maintained her reduced loraz

The third case report from 2000 presents a 35-year-old divorced woman from United States with a history of recurrent depression, panic disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). She struggled for 7 months with IBS-C pre

In our 42-year-old male case presented with a history of chronic diarrhea, intermittent rectal bleeding, and unintentional weight loss of approximately 12% of his total body weight. The patient had been experiencing diarrhea for several months, which improved with dietary modifications, particularly a low FODMAP diet. He reported occasional rectal bleeding and had concerns about weight loss. There were no reports of nocturnal diarrhea, fevers, or systemic symptoms. No significant past medical history was noted. The patient had previously used probiotics (VSL#3) and desvenlafaxine for symptom management. No significant personal or family history of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), colorectal cancer, or celiac disease was reported. The patient appeared well-nourished, with stable vital signs. Abdominal exa

The literature search identified one randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study examining the efficacy of mirtazapine for treating IBS-diarrhoea predominant, published in Iran in 2021. The study included 67 patients meeting the Rome IV criteria for IBS-D, with 34 randomized to receive mirtazapine and 33 to placebo. Mirtazapine was adm

The final paper reviewed was a prospective study from China, published in 2020, involving adult patients meeting the Rome III criteria for IBS-diarrhoea and comorbid depression. Out of 410 recruited patients, 116 received various neu

This systematic review identified five relevant publications—three case reports, one randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial, and one prospective cohort study—demonstrating that Mirtazapine consistently improves IBS-related symptoms (abdominal pain, stool frequency, urgency) and enhances QoL, particularly in IBS-D patients with comorbid anxiety or depression. In our 42-year-old male case with IBS-D and SIBO, the combination of low-FODMAP diet, Rifaximin, and Mirtazapine 15 mg daily produced rapid symptomatic relief and appetite normalization, paralleling the benefit seen in prior case reports of severe, treatment-refractory IBS[9,21,22] and echoing the RCT’s findings of significant reductions in IBS-SSS and anxiety scores[23]. This convergence of evidence across study designs reinforces Mirtazapine’s potential as an effective gut-brain neuromodulator in difficult-to-treat IBS-D, highlighting the value of integrating pharmacologic, dietary, and microbial interventions in personalized management.

Although IBS is generally benign, it incurs significant societal costs, including direct healthcare expenses and indirect costs from work absenteeism (45%) and lost productivity due to unpaid labor (13%). These financial burdens are associated with increased depressive symptoms in IBS patients[10,25].

Recent studies indicate a notable correlation between frailty status and the incidence of IBS in middle-aged and older adults, challenging the prior notion that IBS mainly affects younger populations. This population often remains un

Mirtazapine is utilized in psychiatry for major depression and comorbid depressive-anxiety disorders, as well as depression linked to conditions like epilepsy, Alzheimer’s, and cardiovascular diseases. Its efficacy extends to oncologic patients, improving sadness, nausea, pain, and overall QoL. Additionally, Mirtazapine shows promise in chronic con

A growing body of literature highlights the importance of concurrently targeting both GI and central nervous system pathways in IBS management: A dual gut–brain approach, advocating for combined dietary, antimicrobial, and psychotropic strategies to optimize symptom control[28]. In line with this paradigm, an open-label IBS-D cohort that mirtazapine not only reduced stool frequency and abdominal pain but also improved associated anxiety and depressive symptoms, underscoring its bidirectional efficacy[29]. Pathophysiology-driven treatment models by identifying motility biomarkers and neurotransmitter targets—such as 5-HT3 and neurokinin receptors—that can guide personalized therapy selection[30]. Meanwhile, the broader class of neuromodulators, exemplified by citalopram’s serotonergic modulation profile, offers additional options for patients intolerant of or unresponsive to tricyclics and mirtazapine[31]. Together, these studies advocate for a tailored, biomarker-informed regimen that integrates dietary modification, gut-directed antimicrobials, and targeted neuromodulation to address the multifaceted pathogenesis of IBS.

Mirtazapine, an atypical antidepressant with noradrenergic and serotonergic properties, has shown benefits in functional GI disorders, including IBS. Several RCTs have analyzed Mirtazapine for treating functional dyspepsia in the elderly, showing excellent results[32-36]. Future studies are essential to determine the appropriate patient profile for Mirtazapine as a first-line treatment compared to other neuromodulators, such as tricyclics and SSRIs, which are currently reco

Research on Mirtazapine's prokinetic effects in the GI tract conducted in dogs revealed that it enhances gastric accommodation and accelerates gastric emptying and colonic transit, though it does not affect small bowel transit[15]. Mirtazapine acts as an adrenoreceptor antagonist with a strong affinity for presynaptic alpha 2 adrenoreceptors, which, when blocked, is expected to increase GI motility. Earlier studies demonstrated that Mirtazapine could counteract the GI side effects of Clonidine, which causes delayed gastric emptying and constipation[17]. By blocking alpha 2 receptors, Mirtazapine increases serotonin transmission and 5-HT release. Its high affinity for serotoninergic 5-HT2 receptors—specifically 5-HT2A and 5-HT2C—supports its role in regulating GI motor activity[17]. Mirtazapine is deemed safe and effective for long-term administration[38].

So far, evidence regarding Mirtazapine's use in IBS treatment is limited. However, the only randomized, placebo-controlled study shows encouraging results, demonstrating Mirtazapine's efficacy in improving IBS-related symptoms and QoL. This small study involved 67 patients, with 34 patients in the intervention group, offering minimal demo

A prospective study from 2020 also reported positive outcomes for Mirtazapine in IBS-D patients with comorbid de

Three relevant IBS case reports classified as severe according to the MDCP framework highlighted patients with comorbid psychosocial symptoms, such as anxiety and panic attacks. One patient experienced significant QoL impairment due to IBS, resulting in work absenteeism. All three patients benefited from Mirtazapine treatment, showing overall improvements in QoL. Their ages were 35 years, 52 years, and 66 years, respectively, and all were females.

A 2019 systematic review with meta-analysis found that individuals with IBS had a threefold increase in the odds of anxiety and depression compared to healthy participants[8]. IBS considerably reduces QoL, with estimates indicating that 42%-61% of IBS patients also face mental health concerns: (1) 26.8%-29.4% have major depressive disorder; (2) 16.7%-46.3% have panic disorder; and (3) Up to 37% have generalized anxiety disorder[9]. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial published in 2021 confirmed Mirtazapine's benefits for IBS-D, particularly in patients with psy

A Cochrane review encompassing 29 RCTs and comparing Mirtazapine with SSRIs in patients with depression revealed that Mirtazapine exhibited a faster onset of action than SSRIs. Additionally, Mirtazapine was associated with promoting appetite and with achieving weight gain, while being less likely to cause nausea/vomiting and sexual dysfunction compared to SSRIs[3].

Although IBS is classified as a benign, functional disease, its symptoms can be debilitating for patients. With IBS prevalence estimated at around 10%, it is crucial for clinicians to have a variety of safe, effective, and affordable treatment options. Mirtazapine may be one such option, as it is a safe, inexpensive drug with a good safety profile and tolerability. Its once-daily administration can enhance patient compliance, and it reaches steady-state concentration within 4-6 days, allowing patients to experience benefits relatively quickly.

Mirtazapine may serve as a gut-brain neuromodulator in IBS treatment. Compared to other pharmacological options recommended by IBS guidelines, it has the advantage of not causing sexual dysfunction, a common side effect of SSRIs. Additionally, Mirtazapine can increase appetite and promote weight gain, which may be beneficial for elderly patients or those with chronic conditions already struggling with reduced appetite and weight loss (e.g., malignancies, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cardiovascular disease). Its unique safety profile makes it a viable option for difficult-to-treat IBS patients with comorbid psychiatric issues, such as anxiety and depression[39].

While evidence supporting Mirtazapine's benefits in IBS treatment is limited, the positive impact on IBS patients, including improved QoL, is noted. Mirtazapine appears to relieve bothersome IBS symptoms, such as abdominal pain and diarrhea, particularly in IBS-D patients. The existing evidence primarily involves severe cases with significant psychosocial symptoms who have failed other treatments. Mirtazapine has shown success in female IBS patients with psychiatric symptoms, but there is no specific evidence for its benefits in particular age groups[40].

Given the overlap in symptoms between IBS and other GI conditions, a thorough differential diagnosis is crucial before initiating treatment. Conditions such as IBD[41-44], celiac disease[45,46], microscopic colitis[47], chronic and parasitic infections[48-52], foreign bodies[53], small bowel and colon neoplasms[54], pellagra[55], and drug-induced diarrhea[56-58] can mimic IBS symptoms. Misdiagnosis can lead to inappropriate treatment, prolonged patient distress, and missed opportunities for targeted therapies. Alarm features, such as weight loss, rectal bleeding, nocturnal symptoms, and family history of colorectal cancer or IBD, warrant further investigation with endoscopic, serologic, or stool-based testing. Identifying the correct underlying pathology ensures that patients receive appropriate management while avoiding unnecessary treatments that may be ineffective or even harmful.

This systematic review is limited by the inability to perform a meta-analysis due to significant heterogeneity among included studies and the paucity of data reporting comparable outcomes. The variability in study designs, patient populations, interventions, and outcome measures prevented meaningful quantitative synthesis. Consequently, the absence of a meta-analysis restricts the strength of evidence that can be drawn and limits the ability to estimate pooled effect sizes or assess publication bias statistically. These limitations highlight the need for more standardized, high-quality studies with consistent outcome reporting to facilitate future meta-analytical evaluations and provide more robust clinical guidance.

Patients with IBS often have comorbid depression, with psychiatric conditions estimated to occur in around 50% of these individuals. Conversely, those with psychiatric issues are at a higher risk for developing IBS. Despite being classified as a benign, functional disease, IBS symptoms can be debilitating. Given its prevalence of about 10% in the general po

We extend our appreciation to the Faculty of Life Sciences and Education at the University of South Wales in partnership with Learna Ltd. for the Gastroenterology MSc program and their invaluable support in our work. We sincerely acknowledge the efforts of the University of South Wales and commend them for their commitment to providing life-long learning opportunities and advanced life skills to healthcare professionals.

| 1. | Vasant DH, Paine PA, Black CJ, Houghton LA, Everitt HA, Corsetti M, Agrawal A, Aziz I, Farmer AD, Eugenicos MP, Moss-Morris R, Yiannakou Y, Ford AC. British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines on the management of irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2021;70:1214-1240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 340] [Article Influence: 68.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Holtmann GJ, Ford AC, Talley NJ. Pathophysiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1:133-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 400] [Article Influence: 40.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Watanabe N, Omori IM, Nakagawa A, Cipriani A, Barbui C, Churchill R, Furukawa TA. Mirtazapine versus other antidepressive agents for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;CD006528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | NICE. Irritable bowel syndrome in adults: Diagnosis and Management. 2017. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg61/resources/irritable-bowel-syndrome-in-adults-diagnosis-and-management-pdf-975562917829. |

| 5. | Almario CV, Sharabi E, Chey WD, Lauzon M, Higgins CS, Spiegel BMR. Prevalence and Burden of Illness of Rome IV Irritable Bowel Syndrome in the United States: Results From a Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study. Gastroenterology. 2023;165:1475-1487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Li C, Ying Y, Zheng Y, Li X, Lan L. Epidemiology of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Epidemiol Public Health. 2024;2. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Chang L. How to Approach a Patient with Difficult-to-Treat IBS. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:1092-1098.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Zamani M, Alizadeh-Tabari S, Zamani V. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the prevalence of anxiety and depression in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;50:132-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 300] [Cited by in RCA: 326] [Article Influence: 46.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Akama F, Mikami K, Watanabe N, Kimoto K, Yamamoto K, Matsumoto H. Efficacy of Mirtazapine on Irritable Bowel Syndrome with Anxiety and Depression: A Case Study. J Nippon Med Sch. 2018;85:330-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bosman MHMA, Weerts ZZRM, Snijkers JTW, Vork L, Mujagic Z, Masclee AAM, Jonkers DMAE, Keszthelyi D. The Socioeconomic Impact of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: An Analysis of Direct and Indirect Health Care Costs. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;21:2660-2669. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wu S, Yang Z, Liu S, Zhang Q, Zhang S, Zhu S. Frailty status and risk of irritable bowel syndrome in middle-aged and older adults: A large-scale prospective cohort study. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;56:101807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ting CH, Chen CY. Gut symptoms in the depressed elderly: The interactions between emotion and gastrointestinal neuroendocrinology. J Chin Med Assoc. 2021;84:455-456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Moraczewski J, Awosika AO, Aedma KK. Tricyclic Antidepressants. 2023 Aug 17. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Chu A, Wadhwa R. Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors. 2023 May 1. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Dhaliwal JS, Spurling BC, Molla M. Duloxetine. 2023 May 29. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Jilani TN, Gibbons JR, Faizy RM, Saadabadi A. Mirtazapine. 2024 Nov 9. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Yin J, Song J, Lei Y, Xu X, Chen JD. Prokinetic effects of mirtazapine on gastrointestinal transit. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2014;306:G796-G801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Bahar RJ, Collins BS, Steinmetz B, Ament ME. Double-blind placebo-controlled trial of amitriptyline for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome in adolescents. J Pediatr. 2008;152:685-689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 123] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sandhu BK, Paul SP. Irritable bowel syndrome in children: pathogenesis, diagnosis and evidence-based treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:6013-6023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Veroniki AA, Hutton B, Stevens A, McKenzie JE, Page MJ, Moher D, McGowan J, Straus SE, Li T, Munn Z, Pollock D, Colquhoun H, Godfrey C, Smith M, Tufte J, Logan S, Catalá-López F, Tovey D, Franco JVA, Chang S, Garritty C, Hartling L, Horsley T, Langlois EV, McInnes M, Offringa M, Welch V, Pritchard C, Khalil H, Mittmann N, Peters M, Konstantinidis M, Elsman EBM, Kelly SE, Aldcroft A, Thirugnanasampanthar SS, Dourka J, Neupane D, Well G, Akl E, Wilson M, Soares-Weiser K, Tricco AC. Update to the PRISMA guidelines for network meta-analyses and scoping reviews and development of guidelines for rapid reviews: a scoping review protocol. JBI Evid Synth. 2025;23:517-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 27.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Spiegel DR, Kolb R. Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with comorbid anxiety symptoms with mirtazapine. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2011;34:36-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Thomas SG. Irritable bowel syndrome and mirtazapine. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1341-1342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Khalilian A, Ahmadimoghaddam D, Saki S, Mohammadi Y, Mehrpooya M. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to assess efficacy of mirtazapine for the treatment of diarrhea predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Biopsychosoc Med. 2021;15:3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lu J, Shi L, Huang D, Fan W, Li X, Zhu L, Wei J, Fang X. Depression and Structural Factors Are Associated With Symptoms in Patients of Irritable Bowel Syndrome With Diarrhea. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2020;26:505-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Canavan C, West J, Card T. Review article: the economic impact of the irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:1023-1034. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 262] [Cited by in RCA: 342] [Article Influence: 28.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lim J, Park H, Lee H, Lee E, Lee D, Jung HW, Jang IY. Higher frailty burden in older adults with chronic constipation. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021;21:137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Mostafa-he G, Alanazi M, Abdelmawll H. Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory and Antiapoptotic Effect of Mirtazapine Mitigates Cyclophosphamide-Induced Testicular Toxicity in Rats. Int J Pharmacol. 2023;19:166-177. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Jayasinghe M, Damianos JA, Prathiraja O, Oorloff MD, Nagalmulla K GM, Nadella A, Caldera D, Mohtashim A. Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Treating the Gut and Brain/Mind at the Same Time. Cureus. 2023;15:e43404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Sanagapalli S, Kim E, Zarate-Lopez N, Emmanuel A. Mirtazapine in Diarrhoea-predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome: An Open Label Study. J Gastroenterol Dig Dis. 2018;3:17-21. |

| 30. | Camilleri M, Boeckxstaens G. Irritable bowel syndrome: treatment based on pathophysiology and biomarkers. Gut. 2023;72:590-599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 24.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Sharbaf Shoar N, Fariba KA, Padhy RK. Citalopram. 2023 Nov 7. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Jamshidfar N, Hamdieh M, Eslami P, Batebi S, Sadeghi A, Rastegar R, Dooghaie Moghadam A, Masjedi Arani A. Comparison of the potency of nortriptyline and mirtazapine on gastrointestinal symptoms, the level of anxiety and depression in patients with functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench. 2023;16:468-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Jiang SM, Jia L, Liu J, Shi MM, Xu MZ. Beneficial effects of antidepressant mirtazapine in functional dyspepsia patients with weight loss. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:5260-5266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 34. | Tack J, Ly HG, Carbone F, Vanheel H, Vanuytsel T, Holvoet L, Boeckxstaens G, Caenepeel P, Arts J, Van Oudenhove L. Efficacy of Mirtazapine in Patients With Functional Dyspepsia and Weight Loss. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:385-392.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Choung RS, Cremonini F, Thapa P, Zinsmeister AR, Talley NJ. The effect of short-term, low-dose tricyclic and tetracyclic antidepressant treatment on satiation, postnutrient load gastrointestinal symptoms and gastric emptying: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20:220-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Cao L, Li G, Cao J, Li F, Han W. Randomized clinical trial: the effects of mirtazapine in functional dyspepsia patients. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2025;18:17562848241311129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Khan A, Menon R, Corning B, Cohn S, Kumfa C, Raji M. Mirtazapine for gastrointestinal and neuropsychological symptoms in older adults with irritable bowel syndrome. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2024;18:17562848241278125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Ferreira GE, Abdel-Shaheed C, Underwood M, Finnerup NB, Day RO, McLachlan A, Eldabe S, Zadro JR, Maher CG. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of antidepressants for pain in adults: overview of systematic reviews. BMJ. 2023;380:e072415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Buono JL, Carson RT, Flores NM. Health-related quality of life, work productivity, and indirect costs among patients with irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15:35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 20.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Ford AC, Lacy BE, Talley NJ. Irritable Bowel Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2566-2578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 344] [Cited by in RCA: 430] [Article Influence: 47.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Hracs L, Windsor JW, Gorospe J, Cummings M, Coward S, Buie MJ, Quan J, Goddard Q, Caplan L, Markovinović A, Williamson T, Abbey Y, Abdullah M, Abreu MT, Ahuja V, Raja Ali RA, Altuwaijri M, Balderramo D, Banerjee R, Benchimol EI, Bernstein CN, Brunet-Mas E, Burisch J, Chong VH, Dotan I, Dutta U, El Ouali S, Forbes A, Forss A, Gearry R, Dao VH, Hartono JL, Hilmi I, Hodges P, Jones GR, Juliao-Baños F, Kaibullayeva J, Kelly P, Kobayashi T, Kotze PG, Lakatos PL, Lees CW, Limsrivilai J, Lo B, Loftus EV Jr, Ludvigsson JF, Mak JWY, Miao Y, Ng KK, Okabayashi S, Olén O, Panaccione R, Paudel MS, Quaresma AB, Rubin DT, Simadibrata M, Sun Y, Suzuki H, Toro M, Turner D, Iade B, Wei SC, Yamamoto-Furusho JK, Yang SK, Ng SC, Kaplan GG; Global IBD Visualization of Epidemiology Studies in the 21st Century (GIVES-21) Research Group. Global evolution of inflammatory bowel disease across epidemiologic stages. Nature. 2025;642:458-466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 126.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 42. | El-Hussuna A, Hauer AC, Karakan T, Pittet V, Yanai H, Devi J, Yamamoto-Furusho JK, Sima AR, Desalegn H, Sultan MI, Sharma V, Shehab H, Mrabti L, Queiroz N, Jena A, Darma A, Davidson K, Avellaneda N, Elhadi M, Roslani A, Wickramasinghe D, Cajucom CA, Sebastian S. ECCO consensus on management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in low-and middle-income countries. J Crohns Colitis. 2025;jjaf125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Amadu M, Soldera J. Duodenal Crohn's disease: Case report and systematic review. World J Methodol. 2024;14:88619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Soldera J. Navigating treatment resistance: Janus kinase inhibitors for ulcerative colitis. World J Clin Cases. 2024;12:5468-5472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Shiha MG, Schiepatti A, Manza F, Maimaris S, Aziz I, Sanders DS. Global Prevalence of Celiac Disease in Patients With Rome III and Rome IV Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Soldera J, Coelho GP, Heinrich CF. Life-Threatening Diarrhea in an Elderly Patient. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:26-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | El Hage Chehade N, Ghoneim S, Shah S, Pardi DS, Farraye FA, Francis FF, Hashash JG. Efficacy and Safety of Vedolizumab and Tumor Necrosis Factor Inhibitors in the Treatment of Steroid-refractory Microscopic Colitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2024;58:789-799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Lomazi EA, de Negreiros LMV, Magalhães PVVS, Togni RCS, de Paiva NM, Ribeiro AF, Leal RF. Intestinal paracoccidioidomycosis resembling Crohn's disease in a teenager: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2018;12:108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Thörn M, Rorsman F, Rönnblom A, Sangfelt P, Wanders A, Eriksson BM, Bondeson K. Active cytomegalovirus infection diagnosed by real-time PCR in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective, controlled observational study (.). Scand J Gastroenterol. 2016;51:1075-1080. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Wizenty J, Maibier M, Sigal M. Persistent Abdominal Pain and Diarrhea After Appendectomy-Crohn's Disease Versus Intestinal Tuberculosis. JGH Open. 2025;9:e70157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Inayat F, Nawaz G, Afzal A, Ajmal M, Haider M, Sarfraz M, Haq ZU, Taj S, Ishtiaq R. Isolated Colonic Histoplasmosis in Patients Undergoing Immunomodulator Therapy: A Systematic Review. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2023;11:23247096231179448. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Amoak S, Soldera J. Blastocystis hominis as a cause of chronic diarrhea in low-resource settings: A systematic review. World J Meta-Anal. 2024;12. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Fan Q, Yu S, Xiong DH. Intractable diarrhea caused by a rare rectal foreign body. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2025;41:e12917. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Carvalho JR, Tavares J, Goulart I, Moura Dos Santos P, Vitorino E, Ferreira C, Serejo F, Velosa J. Signet Ring Cell Carcinoma, Ileal Crohn Disease or Both? - A Case of Diagnostic Challenge. GE Port J Gastroenterol. 2018;25:47-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Ravikumar J, Ravikumar D. Chronic Diarrhea and Alcoholism: Unravelling the Connection to Pellagra. Cureus. 2025;17:e82088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Philip NA, Ahmed N, Pitchumoni CS. Spectrum of Drug-induced Chronic Diarrhea. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2017;51:111-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Iwamuro M, Kawano S, Otsuka M. Drug-induced mucosal alterations observed during esophagogastroduodenoscopy. World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30:2220-2232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 58. | Aver GP, Ribeiro GF, Ballotin VR, Santos FSD, Bigarella LG, Riva F, Brambilla E, Soldera J. Comprehensive analysis of sodium polystyrene sulfonate-induced colitis: A systematic review. World J Meta-Anal. 2023;11:351-367. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/