Published online Mar 20, 2026. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v16.i1.107169

Revised: April 21, 2025

Accepted: July 8, 2025

Published online: March 20, 2026

Processing time: 330 Days and 12.5 Hours

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) are common gastrointestinal disorders that significantly impact patients' quality of life and pose a financial burden on healthcare systems. SIBO is characterized by an abnormal increase in small intestinal bacteria, leading to symptoms such as malabsorption, diarrhea, bloating, and abdominal pain. IBS is a functional gast

To analyze and compare the role of Metronidazole, Bismuth, Rifaximin for im

A systematic review was performed on the databases PubMed and Cochrane Library, spanning from 2000 to 2023. Studies eligible for inclusion were observational studies or randomized controlled trials (RCTs) performed on human subjects that examined the use of Metronidazole, Bismuth, or Rifaximin in the management of SIBO and IBS. Two independent reviewers performed data extraction, and resolved discrepancies by consensus. The data extracted consisted study characteristics, patient demographics, intervention details, and outcome measured. Key references were verified and prioritized using Reference Citation Analysis to ensure contemporary relevance and citation impact.

A total of 55 studies, including RCTs and observational studies, met inclusion criteria and were analyzed. These studies assessed the efficacy and safety of Metronidazole, Bismuth, and Rifaximin in patients with SIBO and IBS. Rifaximin demonstrated the most consistent efficacy across both conditions, particularly in IBS-D and mild to moderate SIBO, with a low incidence of adverse events (16.7%). Metronidazole showed moderate efficacy, with some benefit in IBS-C and mild SIBO, but was associated with a higher rate of gastrointestinal side effects (16.6%). Bismuth offered symptom relief in IBS, especially for bloating and diarrhea, though its effectiveness was generally lower than the other agents. Subgroup analyses suggested differential efficacy by IBS subtype and SIBO severity, supporting the potential role of clinical phenotype in guiding antibiotic selection.

Significant clinical efficacy was shown by the drug Rifaximin among IBS-D patients at reducing symptoms, with minimal undesirable adverse effects and a favorable safety profile. Metronidazole was effective in treating SIBO but was generally associated with a higher prevalence of gastrointestinal side effects than the other drugs. How

Core Tip: This study compares the efficacy and safety of Metronidazole, Bismuth, and Rifaximin in managing small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Rifaximin showed the greatest clinical benefit, particularly in diarrhea-predominant IBS patients, with minimal side effects. Metronidazole was effective for SIBO but associated with higher gastrointestinal side effects. Bismuth demonstrated some effectiveness, particularly in combination therapies, but was less pronounced than the other two antibiotics. Further research is needed to optimize treatment strategies and assess long-term outcomes.

- Citation: Shah Q, Soldera J. Exploring effectiveness of Metronidazole, Bismuth, and Rifaximin in treating small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review. World J Methodol 2026; 16(1): 107169

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v16/i1/107169.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v16.i1.107169

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) are highly prevalent gastrointestinal disorders that markedly impair patient quality of life and impose substantial costs on healthcare systems worldwide. Both conditions manifest across a spectrum—from mild discomfort to severe, disabling pain and functional impairment—underscoring the need for optimized diagnostic and therapeutic strategies[1].

SIBO is characterized by an abnormal proliferation of bacteria in the small intestine, where bacterial density is normally low. Predisposing factors include impaired intestinal motility, anatomic abnormalities, liver disease, immune dysfunction, and dietary factors. Bacterial overgrowth disrupts digestion and absorption, resulting in malabsorption, bloating, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, and in severe cases, weight loss and nutritional deficiencies. These symptoms principally arise from bacterial fermentation of carbohydrates, which generates gas and exacerbates bloating[2-4].

IBS, by contrast, is a functional disorder defined by recurrent abdominal pain and altered bowel habits, classified into diarrhoeapredominant IBS (IBSD), constipationpredominant IBS (IBSC), and mixedtype IBS (IBSM) subtypes. Its pathogenesis is multifactorial—encompassing gut-brain axis dysregulation, increased intestinal permeability, microbial dysbiosis, visceral hypersensitivity, and immune activation—yet lacks overt structural abnormalities or a single organic cause[5,6].

A substantial clinical overlap exists between IBSD and SIBO, complicating both diagnosis and management. Epidemiological studies estimate that up to 40%-60% of IBS patients harbor SIBO, suggesting a significant pathogenic association and potential for targeted intervention[7,8]. Indeed, symptom relief in IBSD patients with confirmed SIBO has been observed following antibiotic regimens aimed at reducing smallintestinal bacterial load[9,10].

This overlap appears to be bidirectional: The dysbiosis and motility disturbances characteristic of IBS may predispose to SIBO, while bacterial overgrowth can exacerbate IBSD by further impairing motility and increasing visceral sensitivity[8]. Accordingly, contemporary management paradigms increasingly address SIBO within the broader therapeutic framework for IBS, seeking to correct underlying dysbiosis rather than merely ameliorate symptoms[11].

Historically, empirical broadspectrum antibiotics were employed to treat both SIBO and IBS, but advances in our understanding of gut microbiota have shifted practice toward agents with more targeted activity and improved safety profiles. Among these, Metronidazole, Bismuth subsalicylate, and Rifaximin have garnered particular interest due to their distinct mechanisms of action and clinical profiles.

Metronidazole exerts broad anaerobic coverage by inhibiting DNA synthesis and remains a mainstay for SIBO unresponsive to firstline interventions[12]. However, its utility is limited by adverse effects—nausea, vomiting—and emerging bacterial resistance, which diminish its suitability for repeated courses[12,13].

Bismuth subsalicylate, traditionally used in Helicobacter pylori eradication, possesses antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory properties that can disrupt bacterial adhesion and potentiate coadministered antibiotics. Emerging evidence suggests that, when combined with Metronidazole, Bismuth enhances symptom relief and may reduce resistance risk, although its efficacy as monotherapy in SIBO or IBS remains underexplored[9,14].

Rifaximin is distinguished by its gutselective, nonsystemic activity and minimal systemic absorption, yielding a favorable safety profile. It has demonstrated efficacy in ameliorating IBSD symptoms—abdominal pain and stool irregularity—and in eradicating SIBO in approximately 70% of cases. Nevertheless, its precise mechanism remains incompletely defined, and concerns persist regarding longterm safety and resistance following repeated administration[10,15,16].

The comparative evaluation of these three agents is justified by their differing spectrums of activity, safety profiles, and potential for resistance. Although each has shown symptomatic benefit, robust headtohead data remain scarce. Met

Metronidazole’s introduction in the 1950s established it as an early antianaerobic agent for SIBO[12], while Bismuth compounds later entered SIBO/IBS regimens as part of combination protocols to maximize efficacy and minimize adverse events (AEs)[9]. Rifaximin, first used for travelrelated diarrhoea in the late 1980s, has been embraced for its pharmacokinetic profile that favors high intraluminal concentrations with limited systemic exposure[7].

Recent clinical trials reinforce these agents’ roles: (1) Metronidazole provides symptom relief in approximately 70% of SIBO cases but is hampered by relapse and gastrointestinal intolerance[13]; (2) Combination therapy with Bismuth subsalicylate enhances response rates and tolerability[9]; and (3) The TARGET 3 study confirmed Rifaximin’s capacity to improve IBSD symptoms and eradicate SIBO in approximately 70% of patients, albeit with repeat courses raising resistance concerns[10,16].

Despite their shortterm efficacy, longterm management of SIBO and IBS is challenged by limited data on sustained outcomes, the rise of antibiotic resistance, and an incomplete understanding of microbiome alterations. Given the heterogeneity of these disorders, personalized regimens—tailored to individual microbial profiles, disease severity, and treatment history—may optimize therapeutic outcomes while reducing AEs and resistance development[17].

Finally, while symptom and microbial endpoints have been wellstudied, the broader impact of these treatments on patient quality of life warrants further exploration. Investigations into physical, emotional, and social dimensions of wellbeing, as well as complementary approaches (probiotics, prebiotics, diet, herbal therapies), may yield sustainable, antibioticsparing strategies for longterm management[18-20].

The aim of this study is to determine the efficacy and safety of Metronidazole, Bismuth, and Rifaximin in treating SIBO and IBS, thereby advancing our understanding of their optimal clinical use and informing the development of more effective, personalized treatment protocols.

This study uses a systematic review approach to synthesize and analyze existing data on the efficacy of Metronidazole, Bismuth, and Rifaximin in the treatment of SIBO and IBS. No pre-specified subgroup analysis was planned due to expected heterogeneity. The protocol for this review was registered in the PROSPERO database under the No. CRD

A literature search covering all relevant studies was carried out across multiple databases. These databases included PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science; these databases are among the most comprehensive in biomedical research. Both MeSH and free-text terms were used in the search strategy to ensure that all potential studies were identified.

The search command used was ("irritable bowel syndrome" OR "IBS" OR "SIBO" OR "small intestinal bacterial overgrowth" OR "IMO" OR "intestinal Methanogen Overgrowth") AND ("bismuth" OR "metronidazole" OR "rifaximin"). Only the articles that were published within January 2000 to December 2023 were included. Only studies written in English language were included.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were set to ensure that only studies that were methodologically sound and directly relevant to the research question were included in the meta-analysis.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Study design: Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and cohort studies were considered because of their high evidence level; (2) Population: Research in adult patients aged 18 years and above diagnosed with SIBO or IBS according to established diagnostic criteria, such as the hydrogen breath test for SIBO and Rome IV criteria for IBS; (3) Intervention: Research on Metronidazole, Bismuth, or Rifaximin as a treatment for SIBO or IBS; and (4) Outcomes: Studies that reported on treatment efficacy (e.g., symptom improvement, recurrence) or safety (e.g., AEs).

Exclusion criteria: (1) Study design: Excluded studies were case reports, case series, reviews, and studies without control groups; (2) Population: Pediatric population research or patients with other gastroenterological conditions not concentrated on SIBO and IBS; (3) Intervention: Trials with combination therapies or interventions other than Metronidazole, Bismuth, or Rifaximin; and (4) Outcomes: Studies that failed to report on primary or secondary outcomes of interest were excluded.

The two reviewers independently extracted data using a standardized data extraction form. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus. The extracted data included (1) Study characteristics, such as authors, publication year, and study design; (2) Population details, including age, sex, and diagnostic criteria; (3) Intervention specifics, such as type of antibiotic, dosage, and duration; and (4) Outcomes, such as symptom relief, adverse effects, and recurrence rates.

Pilot data extraction had to be carried out, for a selected sample size of studies, prior to starting full-scale data extractions. This served as fine-tuning the extraction of the data form and ascertained that all data points for inclusion were appropriately extracted into the data extraction tool for each study.

The quality of the studies included in this review was reviewed using Cochrane Risk of Bias tool for RCTs and the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for cohort studies. These tools have been long established for assessing methodological quality in clinical studies. They have been selected so that they can be followed consistently, thereby ensuring to assess risk bias[21].

The Cochrane Risk of bias tool is used to assess a range of domains, such as selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias and reporting bias. Each domain was rated as "low risk", "high risk", or "unclear risk", and an overall risk of bias score was computed for each study.

For cohort studies, the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale is used to evaluate selection, comparability and outcome. Studies that gave 7 or more (with a total score of 9) were classed as high quality, whereas studies giving fewer points (with a total score less than or equal to 9) were classed as high risk of bias.

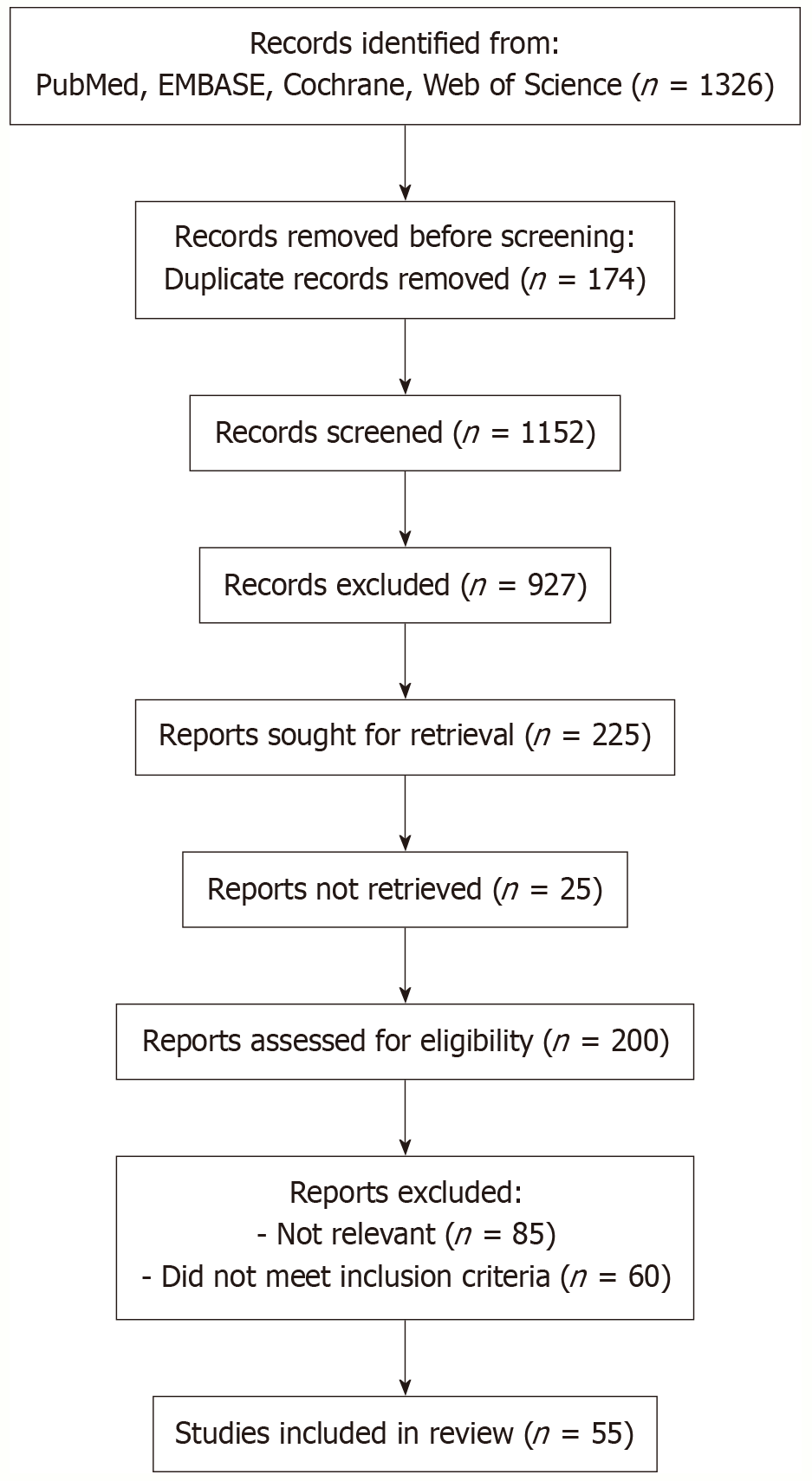

Efficacy data for Metronidazole, Bismuth, and Rifaximin were synthesized using a systematic review approach, which involved the comprehensive identification, assessment, and inclusion of studies that met predefined eligibility criteria. A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram was employed to outline the study selection process, including stages of identification, screening, and inclusion. Due to substantial heterogeneity across the included studies—such as variability in study design, patient populations, dosing regimens, and outcome measures—a formal meta-analysis was not feasible. Instead, data were organized and managed using Microsoft Excel, and a simple frequency analysis was performed. Descriptive statistics, including frequencies and proportions for binary outcomes and means for continuous outcomes, were used to evaluate the primary outcome: The effectiveness of antibiotic therapy in alleviating symptoms of SIBO and IBS.

A total of 1326 records were identified through searches of PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane and Web of Science. After removal of 174 duplicates, 1152 unique records underwent title and abstract screening. Of these, 927 were excluded for irrelevance, leaving 225 reports for fulltext retrieval; 25 could not be obtained. Two hundred fulltext articles were assessed against predefined inclusion criteria, resulting in the exclusion of 85 for lack of relevance and 60 for failure to meet eligibility. Ultimately, 55 studies were included in this review (Figure 1).

The 55 included investigations comprised 30 RCTs and 25 observational cohort studies (Table 1)[22-39]. Sample sizes ranged from 20 to 450 participants. Interventions varied in antibiotic agent (Metronidazole, Bismuth subsalicylate, Rifaximin), dosage (e.g. Metronidazole 250-750 mg twice daily; Rifaximin 400-1100 mg/day), and treatment duration (5 days to 12 weeks). Diagnostic criteria for SIBO (e.g., breath testing) and IBS (Rome criteria) also differed, contributing to clinical and methodological heterogeneity that precluded formal metaanalysis.

| Number | Ref. | Year of publication | Study design and setting | Number of patients enrolled with summary | Intervention used | Comparison used | Patients achieved outcome (intervention group) | Patients achieved outcome (comparison group) |

| 1 | Marie et al[23] | 2009 | Non-randomized, uncontrolled, prospective | 51 | Intermittent rotating antibiotics (7 days/month for 3 months) | None | 21/49 | N/A |

| 2 | Feng et al[24] | 2021 | Non-randomized, prospective | 14 | Antibiotic course | Placebo | 6 | 2 |

| 3 | Menees et al[25] | 2012 | Non-randomized, uncontrolled, prospective | 51 | Norfloxacin and Metronidazole intermittently | None | 11 | N/A |

| 4 | Tauber et al[27] | 2014 | Non-randomized, uncontrolled, prospective | 37 | Amoxicillin, Ciprofloxacin, and Metronidazole in succession | None | 6 | N/A |

| 5 | Mouillot et al[26] | 2020 | Retrospective cohort study | 101 | Gentamicin/Metronidazole and Metronidazole alone | None | 20 | 23 |

| 6 | García-Collinot et al[28] | 2020 | Clinical pilot study | 40 | Metronidazole alone | Saccharomyces boulardii alone | 2 | 4 |

| 7 | Tahan et al[29] | 2013 | Noncontrolled open clinical trial, community-based | 20 | Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (30 mg/kg/day) and Metronidazole (20 mg/kg/day) for 14 days | None | 19 | N/A |

| 8 | Marie et al[23] | 2009 | Prospective observational cohort study, single tertiary care center | 51 | Rotating antibiotic therapy (Norfloxacin/Metronidazole) | None | 22 | N/A |

| 9 | Lauritano et al[30] | 2009 | Randomized controlled trial, catholic university of Rome | 142 | Metronidazole 750 mg/day for 7 days | Rifaximin 1200 mg/day for 7 days | 31 | 45 |

| 10 | Lauritano et al[31] | 2008 | Randomized controlled trial | 142 | Metronidazole 750 mg/day | Rifaximin 1200 mg/day | 53 patients (Metronidazole) | 67 patients (Rifaximin) |

| 11 | Lauritano et al[31] | 2008 | Cross-sectional study | 51 | Rotating antibiotic therapy (Norfloxacin/Metronidazole) | None | 22 patients (improvement) | N/A |

| 12 | Dear et al[32] | 2005 | Clinical trial, hospital-based | 12 | Metronidazole | No fiber diet | 6 patients: Significant reduction in hydrogen and methane production | N/A |

| 13 | Di Stefano et al[33] | 2005 | RCT, hospital setting | 14 | Metronidazole | Rifaximin | 12 patients showed greater improvement in symptom severity | 7 patients showed improvement (Rifaximin) |

| 14 | Di Stefano et al[33] | 2005 | RCT, hospital setting | 14 | Metronidazole | Rifaximin | 12 patients showed greater improvement in symptom severity | 7 patients showed improvement (Rifaximin) |

| 15 | Di Stefano et al[33] | 2005 | RCT, hospital setting | 14 | Metronidazole | Rifaximin | 12 patients showed greater improvement in symptom severity | 7 patients showed improvement (Rifaximin) |

| 16 | Melchior et al[34] | 2017 | Pilot controlled phase II study | 16 | Metronidazole (n = 8, 10 days) | Subcutaneous (n = 8, 10 days) | 7 patients (87.5%) showed > 50% reduction in flatus incontinence episodes (from 18.2 ± 16.2 to 3.5 ± 3.1 episodes) | 1 patient (12.5%) showed > 50% reduction in flatus incontinence episodes (from 11.1 ± 12 to 8 ± 9.7 episodes) |

| 17 | Thakur et al[35] | 2009 | Randomized, controlled | 24 | Metronidazole, 7 days | None | 9 (improvement in stool scores) | 0 (not reported) |

| 18 | Richard et al[36] | 2021 | Retrospective, single-center study | 223 | Metronidazole (500 mg, 3 ×/day for 10 days/month for 3 months) | Single antibiotic (Metronidazole) vs rotating antibiotics | 36/69 (52.2%) achieved remission | 62/124 (50.0%) achieved remission |

| 19 | Richard et al[36] | 2021 | Retrospective, single-center study | 223 | Metronidazole (500 mg, 3 ×/day for 10 days/month for 3 months) + Norfloxacin (400 mg, 2 ×/day for 10 days/month for 3 months) or Metronidazole + Ofloxacin | Rotating antibiotics vs single antibiotics | 21/30 (70.0%) achieved remission | 62/124 (50.0%) achieved remission |

| 20 | Pérez Aisa et al[37] | 2019 | Prospective cohort study, single-center | 60 | Rifaximin, Metronidazole, Ciprofloxacin | None | 12 patients (small intestinal bacterial overgrowth + group, after treatment) | N/A |

| 21 | Konrad et al[38] | 2018 | Randomized single-blind clinical trial | 116 | Pantoprazole 2 × 40 mg, Amoxicillin 2 × 1000 mg, Metronidazole 2 × 500 mg for 10 days | Pantoprazole 2 × 40 mg, Amoxicillin 2 × 1000 mg, Rifaximin 3 × 400 mg for 10 days | 18 (normal LHBT); 19 (UBT < 4.0‰); pain reduced below 3 points in 16 | 21 (normal LHBT); 19 (UBT < 4.0‰); pain reduced below 3 points in 18 |

| 22 | Peinado Fabregat et al[39] | 2022 | Retrospective cohort study | 54 | Antibiotics (Metronidazole, Rifaximin, other) + probiotics | None | 39 (partial/full symptom improvement) | N/A |

| 23 | Peinado Fabregat et al[39] | 2022 | Retrospective cohort study | 54 | Metronidazole + probiotics | None | 13 (81.2) | 10 (32.3) |

| 24 | Peinado Fabregat et al[39] | 2022 | Retrospective cohort study | 54 | Metronidazole | None | 7 (36.8) | 7 (36.8) |

| 25 | Peinado Fabregat et al[39] | 2022 | Retrospective cohort study | 54 | Antibiotics (Metronidazole, Rifaximin, other) | None | 12 (63.2) | 9 (32.0) |

| 26 | Peinado Fabregat et al[39] | 2022 | Retrospective cohort study | 54 | Metronidazole, Rifaximin | None | 12 (71.4) | N/A |

| 27 | Lauritano et al[30] | 2009 | Open-Label randomized trial | 71 intervention each group | Rifaximin (1200 mg/day) | Metronidazole (750 mg/day) | 45 | 31 |

| 28 | Castiglione et al[22] | 2003 | Open-Label randomized trial | 15 intervention, 14 placebo | Metronidazole (750 mg/day) | Ciprofloxacin (1000 mg/day) | 13 | 14 |

Findings from the included studies suggest that Rifaximin demonstrated the highest and most consistent efficacy across SIBO and IBS populations (Table 2)[4,26,30,31,33,37-135]. Symptom relief—or, in SIBO studies, bacterial overgro

| Number | Ref. | Year of publication | Number of patients enrolled with summary | Intervention used | Comparison used | Patients achieved outcome (intervention group) | Patients achieved outcome (comparison group) |

| 1 | Schmulson and Frati-Munari[41] | 2019 | 1851 | Proton pump inhibitors | None | 1333/1851 | Not specified |

| 2 | Pimentel et al[43] | 2011 | 87 | Rifaximin 550 mg 3 times a day for 14 days | Placebo | Abdominal bloating: 10/38; abdominal pain: 11/41; stool consistency: 8/47 | Abdominal bloating: 5/35; abdominal pain: 4/40; stool consistency: 8/44 |

| 3 | Sharara et al[77] | 2006 | 126 | Rifaximin 550 mg 3 times a day for 14 days | Placebo | Abdominal bloating: 10/38; abdominal pain: 11/41; stool consistency: 8/47 | Abdominal bloating: 22/42; abdominal pain: 21/44; stool consistency: 20/43 |

| 4 | Kaye et al[44] | 1995 | 20 | Rifaximin 550 mg three times daily for 14 days | None | 10 | N/A |

| 5 | Parodi et al[42] | 2021 | 55 | Rifaximin 400 mg 3 times/day for 10 days | None | 22 | N/A |

| 6 | Mozaffari et al[45] | 2014 | 1258 (Phase III) | Rifaximin (550 mg three times daily) | Placebo | 1022 | N/A |

| 7 | Shah et al[46] | 2022 | 21 | Rifaximin 550 mg BID for 10 days | None | 17 | N/A |

| 8 | Shah et al[47] | 2012 | 1187 | Rifaximin 400 mg 3 times/day for 10 days | Placebo | 846 | N/A |

| 9 | Shah et al[47] | 2012 | 623 | Rifaximin 550 mg 3 times/day for 14 days | Placebo | 846 | N/A |

| 10 | Colecchia et al[48] | 2006 | 636 | B. longum W11 (5 × 109 cells) | None | 509 | N/A |

| 11 | Fanigliulo et al[49] | 2006 | 70 | Rifaximin followed by B. longum W11 | Rifaximin alone | 57 | N/A |

| 12 | Di Pierro et al[50] | 2021 | 45 | Rifaximin + B. longum W11 | Rifaximin alone | 9 | N/A |

| 13 | Safwat et al[51] | 2020 | 96 | Rifaximin 550 mg three times daily for 2-4 weeks | N/A (single-arm study) | 66 | N/A |

| 14 | Li et al[52] | 2020 | 30 | 400 mg Rifaximin orally, three times daily for 2 weeks | Healthy controls (no medication) | 10 | 4 |

| 15 | Mouillot et al[26] | 2020 | 101 | Rifaximin (550 mg in morning and evening for 7 days) | None | 3 | N/A |

| 16 | Barkin et al[53] | 2019 | 443 | Rifaximin 550 mg TID for 14 days | Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | 47.4% (for hydrogen-positive) | 75% (3/4 on amoxicillin-clavulanic acid) |

| 17 | Lee et al[54] | 2019 | 198 | Rifaximin treatment for 4-12 weeks | None | 162 | N/A |

| 18 | Ghoshal et al[55] | 2018 | 23 | Rifaximin (400 mg thrice daily for 14 days) | Placebo | 6 | 0 |

| 19 | Tuteja et al[56] | 2019 | 50 | Rifaximin 550 mg, twice daily for 2 weeks | Placebo | N/A | N/A |

| 20 | Oh et al[57] | 2018 | 776 | Rifaximin | None | Increased from 22.7% (2006) to 66.7% (2016) | N/A |

| 21 | Furnari et al[58] | 2019 | 23 | Rifaximin (1200 mg for 14 days) | None | 9 out of 10, 4 out of 10 in Rifaximin group | 2 out of 6, 2 out of 6 |

| 22 | Jo et al[59] | 2018 | 25 | Rifaximin (800 mg twice daily for 14 days) | None | 6 | N/A |

| 23 | Moraru et al[60] | 2014 | 331 | Rifaximin 1200 mg/day for 7 days | Control group (20 IBS patients without antibiotic therapy) | 49 | 1 |

| 24 | Moraru et al[60] | 2014 | 331 | Rifaximin 1200 mg/day for 7 days | Control group (20 IBS patients without antibiotic therapy) | 76 | 0 |

| 25 | Pimentel et al[61] | 2014 | 37 (32 included in ITT analysis) | Rifaximin + Neomycin | Neomycin + placebo | 15 | 11 |

| 26 | Kim et al[62] | 2019 | 529 | Rifaximin treatment for SIBO | None | 60 | N/A |

| 27 | Rosania et al[63] | 2013 | 40 (14 males, 26 females) | Rifaximin 400 mg/day for 7 days followed by Lactobacillus case | Rifaximin followed by short chain fructo-oligosaccharides | 33 | 27 |

| 28 | Dima et al[64] | 2012 | 15 | Seven days of Rifaximin + 10 days of probiotics | None | 14 | N/A |

| 29 | Weinstock et al[65] | 2011 | 16 (14 included in analysis) | Rifaximin 550 mg three times daily for 10 days | None | 8 | N/A |

| 30 | Pimentel et al[43] | 2011 | 1260 | Rifaximin 550 mg, three times daily for 2 weeks | Placebo | 511 | 402 |

| 31 | Chang et al[66] | 2011 | 50 | Rifaximin 1200 mg daily for 10 days | Placebo | N/A | N/A |

| 32 | Pimentel et al[67] | 2011 | 552 | Rifaximin 1200 mg daily for 10 days | None | 111 | N/A |

| 33 | Pimentel et al[67] | 2011 | 552 | Rifaximin retreatment | None | 414 | N/A |

| 34 | Pimentel et al[67] | 2011 | 552 | Rifaximin retreatment | None | Median time to relapse: > 4 months | N/A |

| 35 | Collins et al[68] | 2011 | 75 children with community-acquired pneumonia | Rifaximin 550 mg TID for 10 days | Placebo 550 mg TID for 10 days | 44 children normalized their LBT, 20% normalized breath test | 19 children normalized their breath test |

| 36 | Low et al[69] | 2010 | 100 | Rifaximin, Neomycin | Rifaximin, Neomycin, placebo | 87 patients with Rifaximin + Neomycin (Methane eradicated) | 28 patients with Rifaximin alone, 33 with Neomycin alone |

| 37 | Parodi et al[70] | 2009 | 130 IBS, 70 FB, 70 controls | Rifaximin for SIBO | Healthy controls, IBS without SIBO, FB without SIBO | 17 out of 24 positive GBT patients achieved normalization; 15 out of 17 showed GISS improvement | N/A |

| 38 | Lauritano et al[30] | 2009 | 142 | Rifaximin 1200 mg/day for 7 days | Metronidazole 750 mg/day for 7 days | 45 | 31 |

| 39 | Lauritano et al[31] | 2008 | 142 | Rifaximin 1200 mg/day | Metronidazole 750 mg/day | 67 patients (Rifaximin) | 53 patients (Metronidazole) |

| 40 | Lauritano et al[31] | 2008 | 200 | Antibiotic therapy (Rifaximin or other) | None | 134 patients (Rifaximin) | N/A |

| 41 | Lauritano et al[31] | 2008 | 130 | Rifaximin 1200 mg/day | None | 82 patients | N/A |

| 42 | Lauritano et al[31] | 2008 | 142 | Rifaximin 1200 mg/day | None | 90 patients (SIBO resolution) | N/A |

| 43 | Lauritano et al[31] | 2008 | 80 | Rifaximin 1200 mg/day | None | 55 patients (Rifaximin group) | N/A |

| 44 | Parodi et al[42] | 2008 | 55 patients (30 with SIBO) | Rifaximin 1200 mg/day for 7 days | None | 22 | N/A |

| 45 | Weinstock et al[71] | 2008 | 13 | Rifaximin 1200 mg/day for 10 days | None | 10 of 13 patients (77%) achieved ≥ 80% improvement in RLS symptoms. The 5 of 13 achieved 100% resolution of RLS symptoms | N/A |

| 46 | Weinstock et al[71] | 2008 | 13 | Rifaximin 400 mg 3 times/day for 10 days (for two patients) | None | 2 | N/A |

| 47 | Weinstock et al[71] | 2008 | 13 | Rifaximin 800 mg/day for 12 months (for propositus patient) | None | 1 | N/A |

| 48 | Weinstock et al[72] | 2008 | 17 patients with IC and GI symptoms | Rifaximin (10-day course) | None | 7 patients with moderate to great improvement in IC, 12 patients with moderate to great improvement in GI | N/A |

| 49 | Weinstock et al[72] | 2008 | 17 patients with IC and GI symptoms | Rifaximin (10-day course) | None | 7 patients with moderate to great improvement in IC and GI symptoms | N/A |

| 50 | Weinstock et al[72] | 2008 | 17 patients with IC and GI symptoms | Rifaximin (10-day course) | None | 5 patients with flat-line test results | N/A |

| 51 | Weinstock et al[72] | 2008 | 17 patients with IC and GI symptoms | Rifaximin (10-day course) | None | 12 patients with moderate to great improvements in GI and 7 patients with moderate to great improvements in IC | N/A |

| 52 | Yang et al[73] | 2008 | 98 | Rifaximin 1200 mg/day | Non-Rifaximin antibiotics (Neomycin, Doxycycline, Augmentin) | 58 (first response), 16 (retreatment) | 27 (non-Rifaximin antibiotics), 2 (retreatment with Doxycycline, Augmentin, Neomycin) |

| 53 | Yang et al[73] | 2008 | 61 | Various non-Rifaximin antibiotics | Rifaximin | N/A | 27 (first response), 2 (retreatment) |

| 54 | Fanigliulo et al[49] | 2006 | 41 | Rifaximin 400 mg for 10 days/month + B. longum W11 (granulated suspension for 6 days on alternate weeks) | Rifaximin 400 mg for 10 days/month | 41 (reported improvement in symptoms, P = 0.010) | 29 (group B) |

| 55 | Fanigliulo et al[49] | 2006 | 29 | Rifaximin 400 mg for 10 days/month | Rifaximin + B. longum W11 (group A) | 29 (reported improvement in symptoms, P = 0.002) | 41 (group A) |

| 56 | Oh et al[74] | 2025 | 70 | Rifaximin 200 mg four times daily for 14 days | Rifaximin 200 mg four times daily for 14 days and probiotics once daily for 28 days | IBS-SSS score were 65.7% in the combination therapy group | IBS-SSS score were 31.4% in the monotherapy group |

| 57 | Pimentel et al[75] | 2006 | 87 | Rifaximin | Placebo | 43 | 44 |

| 58 | Peralta et al[76] | 2009 | 97 | Rifaximin 1200 mg/day for 7 days | None | 28 patients (BTLact turned negative; symptom score reduced from 2.3 to 0.9) | 26 patients (BTLact still positive; symptom score unchanged) |

| 59 | Sharara et al[76] | 2006 | 124 | Rifaximin (550 mg, 3 ×/day) | Placebo | 26/63 (Phase 2), 18/63 (Phase 3) | 14/61 (Phase 2), 7/61 (Phase 3) |

| 60 | Tursi et al[78] | 2003 | 15 | Rifaximin 800 mg/day for 1 week | None | 10 (all symptoms resolved) | N/A |

| 61 | Corazza et al[79] | 1988 | 6 | Rifaximin 800 mg/day for 5 days | None | 4 patients with negative hydrogen breath test | N/A |

| 62 | Corazza et al[79] | 1988 | 6 | Rifaximin 1200 mg/day for 5 days | None | 4 patients with negative hydrogen breath test | N/A |

| 63 | Scarpellini et al[80] | 2013 | 40 | 40 children with IBS, 64% SIBO-positive | None | 25 patients symptom improvement seen in those with normalized LBT | N/A |

| 64 | Zhuang et al[81] | 2020 | 78 | Patients with IBS-D | None | 45 | N/A |

| 65 | Chojnacki et al[82] | 2022 | 80 | Rifaximin 550 mg/day for 2 weeks | None | 40 | N/A |

| 66 | Chojnacki et al[82] | 2022 | 80 | Rifaximin 550 mg/day for 2 weeks | None | 40 | N/A |

| 67 | Rezaie et al[83] | 2019 | 93 (LBT sub study) | 2-week Rifaximin course | Placebo | Abdominal pain (Rifaximin + LBT-positive): 37/62; bloating (Rifaximin + LBT-positive): 37/62; stool consistency (Rifaximin + LBT-positive): 37/62; IBS symptoms (Rifaximin + LBT-positive): 37/62 | Abdominal pain (Rifaximin + LBT-negative): 8/31; bloating (Rifaximin + LBT-negative): 7/31; stool consistency (Rifaximin + LBT-negative): 7/31; IBS symptoms (Rifaximin + LBT-negative): 8/31 |

| 68 | Rezaie et al[83] | 2019 | 93 | 2-week Rifaximin course | Placebo | 7/45 (15.6%) no symptom recurrence (overall response group) | N/A |

| 69 | Di Stefano et al[33] | 2005 | 14 | Rifaximin | Metronidazole | 7 patients showed improvement in symptom severity | 10 patients showed improvement (Metronidazole) |

| 70 | Di Stefano et al[33] | 2005 | 14 | Rifaximin | Metronidazole | 7 patients showed improvement in symptom severity | 10 patients showed improvement (Metronidazole) |

| 71 | Di Stefano et al[33] | 2005 | 14 | Rifaximin | Metronidazole | 7 patients showed improvement in symptom severity | 10 patients showed improvement (Metronidazole) |

| 72 | Scarpellini et al[84] | 2007 | 162 | Rifaximin 1600 mg/day | Rifaximin 1200 mg/day | 85 patients normalized GBT, 75% symptom relief | 69 patients normalized GBT, 60% symptom relief |

| 73 | Furnari et al[85] | 2010 | 77 | Rifaximin + PHGG | Rifaximin alone | 34/40 (SIBO eradication, ITT analysis) | 23/37 (SIBO eradication, ITT analysis) |

| 74 | Furnari et al[85] | 2010 | 77 | Rifaximin + PHGG | Rifaximin alone | 31/34 (symptomatic improvement in eradicated patients) | 20/23 (symptomatic improvement in eradicated patients) |

| 75 | Meyrat et al[86] | 2012 | 150 | Rifaximin (550 mg, 3 times daily for 14 days) | None | 106 (bloating), 106 (diarrhea), 106 (flatulence), 106 (pain), 106 (reduced well-being) | N/A |

| 76 | Schoenfeld et al[87] | 2014 | 1103 | Rifaximin (550 mg and extended-release 800-2400 mg/day) | Placebo | 579 patients (any AE), 59 (headache), 50 (URTI), 48 (nausea), 41 (abdominal pain), 37 (diarrhea), 37 (UTI) | 436 patients (any AE), 51 (headache), 47 (URTI), 31 (nausea), 39 (abdominal pain), 26 (diarrhea), 18 (UTI) |

| 77 | Tursi et al[88] | 2005 | 90 | Rifaximin + Mesalazine for 10 days, then Mesalazine alone for 8 weeks | None | SIBO eradicated in 52 of 53 patients (all but one patient) | N/A |

| 78 | Ohkubo et al[89] | 2023 | 12 | Rifaximin (4-week treatment) | Placebo | 3 patients (75%) achieved SIBO eradication at week 4 | 0 patients achieved SIBO eradication at week 4 |

| 79 | Cash et al[90] | 2017 | 2579 | Rifaximin (550 mg, 3 times/day, 14 days) | Placebo | 561 patients (52.2% of 1074 responders in open-label), 245 patients (38.6% of 636 in double-blind Rifaximin group) | 188 patients (29.6% of 636 in double-blind placebo group) |

| 80 | Cash et al[90] | 2017 | 636 | Rifaximin (550 mg, 3 times/day for 14 days) | Placebo | 245 patients (38.6% of 636) achieved MCID | 188 patients (29.6% of 636) achieved MCID |

| 81 | Jolley[91] | 2011 | 162 | Rifaximin 1200 mg/day | None | 79 (global improvement ≥ 50%) | N/A |

| 82 | Jolley[91] | 2011 | 81 | Rifaximin 2400 mg/day | None | 38 (global improvement ≥ 50%) | N/A |

| 83 | Jolley[91] | 2011 | 24 | Rifaximin 2400 mg/day | None | 13 (global improvement ≥ 50%) | N/A |

| 84 | Jolley[91] | 2011 | 16 | Rifaximin 2400 mg/day | None | 6 (global improvement ≥ 50%) | N/A |

| 85 | Chedid et al[40] | 2014 | 67 | Rifaximin (oral, non-absorbable antibiotic) | Herbal therapy | 23 (34) | 17 (46) |

| 86 | Vicari et al[92] | 2014 | 95 | Rifaximin (200 mg, 2 tablets BID for 7 days a month) and VSL#3 (450 × 109 CFU/day) | None | 16 patients (6Tx/6-) had positive sperm culture after 12 months of treatment | 3 patients (12-) had positive sperm culture after 12 months with no treatment |

| 87 | Vicari et al[92] | 2014 | 95 | Rifaximin (200 mg, 2 tablets BID for 7 days a month) and VSL#3 (450 × 109 CFU/day) | None | 9 patients (12Tx) achieved positive sperm culture | 16 patients (6Tx/6-) achieved positive sperm culture |

| 88 | Vicari et al[92] | 2014 | 95 | Rifaximin (200 mg, 2 tablets BID for 7 days a month) and VSL#3 (450 × 109 CFU/day) | None | 8 patients (6Tx/6-) had stable prostatitis | 24 patients (12-) had worsening prostatitis (prostate-vesiculitis/prostate-vesiculo-epididymitis) |

| 89 | Liu et al[93] | 2022 | 127 | Rifaximin (200 mg × 3 per day for 4 weeks) | Placebo | 24 patients and IBSN (15 patients) IBS-SSS abdominal pain significantly decreased in both patients with breath test positive | IBSN patients had no significant changes in Bowel Symptom Frequency scores or abdominal pain, minor improvements noted in IBS-SSS |

| 90 | Lembo et al[94] | 2020 | 2579 (open-label); 328 (double-blind) | Rifaximin 550 mg TID for 2 weeks | Placebo | 170/328 | 131/308 |

| 91 | Lembo et al[94] | 2020 | 328 (second treatment course) | Repeat Rifaximin 550 mg TID | Placebo | 131/308 | 123/275 |

| 92 | Castiglione et al[95] | 2024 | 124 | Rifaximin | Placebo | 44/64 NIH-CPSI, 40/64 IBS-SSS, IL-6 reduction, IL-10 increase, Leukocyte decrease | 2/60 NIH-CPSI, 3/60 IBS-SSS, IL-6 increase, IL-10 increase, Leukocyte decrease |

| 93 | Zhang et al[96] | 2015 | 60 | Rifaximin therapy | Placebo | 11 out of 26 reduced minimal hepatic encephalopathy (42.3%) | N/A |

| 94 | Chojnacki et al[97] | 2021 | 80 (40 SIBO-D, 40 SIBO-C) | Rifaximin 1200 mg daily for 14 days | None | Decreased LHBT hydrogen (12/40 in both groups had < 20 ppm post-treatment); decreased 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid | N/A |

| 95 | Bae et al[98] | 2015 | 36 | Rifaximin 4 weeks | None | 51 abdominal pain/discomfort improvement, 45/36 bloating improvement, 54 diarrhea improvement, 25 fatigue improvement | N/A |

| 96 | Bae et al[98] | 2015 | 43 | Rifaximin 8 weeks | None | 38 abdominal pain/discomfort improvement, 45/36 bloating improvement, 41 diarrhea improvement, 32 fatigue improvement | N/A |

| 97 | Bae et al[98] | 2015 | 23 | Rifaximin 12 weeks | None | 51 abdominal pain/discomfort improvement, 45/36 bloating improvement, 54 diarrhea improvement, 23 fatigue improvement | |

| 98 | Black et al[99] | 2020 | 9844 | Rifaximin 550 mg three times daily | Placebo | 3938 | 4922 |

| 99 | DuPont et al[100] | 2005 | 210 | Rifaximin 200 mg daily, BID, TID | Placebo | 153 (73% efficacy) | 57 (27% efficacy) |

| 100 | Riddle et al[101] | 2007 | 95 | Rifaximin 1100 mg daily | Placebo | 64 (67% efficacy) | 31 (33% efficacy) |

| 101 | Martinez-Sandoval et al[102] | 2010 | 201 | Rifaximin 600 mg daily | Placebo | 137 (68% efficacy) | 64 (32% efficacy) |

| 102 | Flores et al[103] | 2011 | 98 | Rifaximin 550 mg daily | Placebo | 28 (28% efficacy) | 70 (72% efficacy) |

| 103 | Shah et al[104] | 2023 | 1112 | Antibiotic therapy | Healthy controls | 669 Patients 60% of systemic sclerosis-patients showed symptom improvement | N/A |

| 104 | Khaw et al[105] | 2022 | 328 (7-63 patients per study) | PERT, Rifaximin, Colesevelam | None | Improvement reported in all intervention groups | N/A |

| 105 | Wang et al[106] | 2021 | 874 | Rifaximin (400-1600 mg/day) | Placebo/active controls | 516 (ITT: 59%) | N/A |

| 106 | Petrone et al[107] | 2011 | 57 | Rifaximin (2-week course) | None | 45 (SIBO positive) | N/A |

| 107 | Pérez Aisa et al[37] | 2019 | 60 | Rifaximin, Metronidazole, Ciprofloxacin | None | 12 patients (SIBO+ group, after treatment) | N/A |

| 108 | Boltin et al[108] | 2014 | 19 | Rifaximin 400 mg × 3/day for 14 days | None | 8 | N/A |

| 109 | Lacy et al[109] | 2023 | 9255 | Rifaximin (14-day course; avg. duration 0.6 months; 1.2 fills) | Eluxadoline (30-day course; avg. duration 3.5 months; 2.9 fills) | TFI ≥ 30 days: 5412 | TFI ≥ 30 days: 1441 |

| 110 | Pimentel et al[110] | 2017 | 103 | Rifaximin | Placebo | Decreased MIC50 values at week 23 for Bacteroides, high susceptibility for Clostridioides difficile | Similar susceptibility to Rifaximin and Rifampin in placebo |

| 111 | Pimentel et al[110] | 2017 | 103 | Rifampin | Placebo | Higher MIC for Bacteroides, consistent susceptibility in Enterobacteriaceae | Higher MIC for Bacteroides, similar susceptibility in Enterobacteriaceae |

| 112 | Fodor et al[111] | 2019 | 103 | Rifaximin (550 mg, three times daily) | Placebo | 37 (based on significant shifts in microbial taxa) | 36 (small shifts, non-significant) |

| 113 | Parodi et al[112] | 2008 | 113 | Rifaximin 400 mg every 8 hours for 10 days | Placebo | 20 (from Rifaximin group) | 0 (from placebo group) |

| 114 | Parodi et al[112] | 2008 | 113 | Rifaximin 400 mg every 8 hours for 10 days | Placebo | 6 (from Rifaximin group) | 0 (from placebo group) |

| 115 | Parodi et al[112] | 2008 | 113 | Rifaximin 400 mg every 8 hours for 10 days | Placebo | 2 (from Rifaximin group) | 2 (from placebo group) |

| 116 | Lembo et al[113] | 2016 | 636 | Rifaximin 550 mg TID | Placebo | 125 | 97 |

| 117 | Lembo et al[113] | 2016 | 636 | Rifaximin 550 mg TID | Placebo | 39 | 20 |

| 118 | Lembo et al[113] | 2016 | 636 | Rifaximin 550 mg TID | Placebo | 56 | 36 |

| 119 | Lembo et al[113] | 2016 | 636 | Rifaximin 550 mg TID | Placebo | 153 | 127 |

| 120 | Majewski et al[114] | 2007 | 20 | Rifaximin 800 mg/day for 4 weeks | None | 15 (symptom improvement) + 10 (GBT normalization) | N/A |

| 121 | Konrad et al[38] | 2018 | 116 | Pantoprazole 2 × 40 mg, Amoxicillin 2 × 1000 mg, Rifaximin 3 × 400 mg for 10 days | Pantoprazole 2 × 40 mg, Amoxicillin 2 × 1000 mg, Metronidazole 2 × 500 mg for 10 days | 21 (normal LHBT); 19 (UBT < 4.0‰); pain reduced below 3 points in 18 | 18 (normal LHBT); 19 (UBT < 4.0‰); pain reduced below 3 points in 16 |

| 122 | Peinado Fabregat et al[39] | 2022 | 54 | Antibiotics (Metronidazole, Rifaximin, other) + probiotics | None | 39 (partial/full symptom improvement) | N/A |

| 123 | Peinado Fabregat et al[39] | 2022 | 54 | Rifaximin + probiotics | None | 13 (76.5) | 8 (32.0) |

| 124 | Peinado Fabregat et al[39] | 2022 | 54 | Rifaximin | None | 13 (76.5) | 13 (77.3) |

| 125 | Peinado Fabregat et al[39] | 2022 | 54 | Antibiotics (Metronidazole, Rifaximin, other) | None | 12 (63.2) | 9 (32.0) |

| 126 | Peinado Fabregat et al[39] | 2022 | 54 | Metronidazole, Rifaximin | None | 12 (71.4) | N/A |

| 127 | Vicari et al[115] | 2017 | 160 (45 type IIIa + IBS, 40 type IIIb + IBS, 75 IBS alone) | Rifaximin followed by VSL#3 probiotics | None | 32/45 (type IIIa), 10/40 (type IIIb) for NIH-CPSI; 35/45 (type IIIa) and 13/40 (type IIIb) for IBS-SSS | N/A |

| 128 | Pimentel et al[43] | 2011 | 1260 (623 in TARGET 1, 637 in TARGET 2) | Rifaximin 550 mg 3 times/day for 14 days | Placebo 3 times/day for 14 days | 309 (TARGET 1)/316 (TARGET 2) in Rifaximin group | 314 (TARGET 1)/320 (TARGET 2) in placebo group |

| 129 | Peralta et al[76] | 2009 | 97 | Rifaximin 1200 mg/day for 7 days | None | 28 patients: BTLact negative, significant symptom reduction (P = 0.003) | 26 patients: BTLact still positive, no symptom change |

| 130 | Muratore et al[116] | 2023 | N/A (model-based study) | Rifaximin 550 mg 3 × daily for 2 weeks (hydrogen breath test-directed) | TCA | N/A (model estimate) | N/A (model estimate) |

| 131 | Lacy et al[109] | 2023 | 1258 + 2438 (open-label phase) | 550 mg Rifaximin TID for 2 weeks | Placebo | 624 (from Trials 1 and 2); 2438 (open-label) | 634 |

| 132 | Shah et al[117] | 2019 | 624 | Rifaximin 550 mg TID for 2 weeks | TCA | 254 | 66 |

| 133 | Enko et al[118] | 2016 | 125 | Rifaximin 600 mg/day for 10 days | None | 26/30 | N/A |

| 134 | Gravina et al[119] | 2015 | 9 | Rifaximin for SIBO eradication | Placebo/no treatment for SIBO | 3/4 patients with isolated SIBO eradicated | 1/2 patients with SIBO non-eradicated |

| 135 | Pimentel et al[43] | 2011 | 1260 | Rifaximin 550 mg TID for 2 weeks | Placebo | 254 | 201 |

| 136 | Sherwin et al[120] | 2020 | 73 | Rifaximin 550 mg TID for 14 days | None | 17/23 high adherers reported improvement | 22/50 Low adherers reported improvement |

| 137 | Zeber-Lubecka et al[121] | 2016 | 31 | Rifaximin 1200 mg/day for 10 days | None | 21 | N/A |

| 138 | Zeber-Lubecka et al[121] | 2016 | 11 | Rifaximin 1200 mg/day for 10 days | None | 7 | N/A |

| 139 | Zeber-Lubecka et al[121] | 2016 | 30 | Rifaximin 1200 mg/day for 10 days | None | 16 | N/A |

| 140 | Pimentel et al[4] | 2003 | 126 | Rifaximin 400 mg TID for 10 days | Placebo | 84 (of 111 IBS patients) | 3 (of 15 controls) |

| 141 | Shah et al[122] | 2010 | 1585 | Breath Test (hydrogen and methane) | Healthy controls | 1076 | 509 |

| 142 | Meyrat et al[86] | 2012 | 150 | Rifaximin 550 mg TID for 14 days | None | 106 | N/A |

| 143 | Ford et al[123] | 2018 | 1805 | Rifaximin (550 mg TID for 14 days) | Placebo | 810 | 651 |

| 144 | Fodor et al[111] | 2019 | 636 | Rifaximin (repeated courses, 2 × 14 days) | Placebo | 290 | 216 |

| 145 | Enko and Kriegshäuser[124] | 2017 | 50 | Rifaximin | None | 30 | N/A |

| 146 | Pimentel et al[4] | 2003 | 111 | Rifaximin | Placebo | 41 | 23 |

| 147 | Wigg et al[125] | 2001 | 43 | Rifaximin | Placebo | 28 | 15 |

| 148 | Song et al[126] | 2021 | 88 | Antibiotics | None | 55 | N/A |

| 149 | Collins et al[68] | 2011 | 49 intervention, 26 placebo | Rifaximin (1650 mg/day) | Placebo | 9 | 3 |

| 150 | Chang et al[66] | 2011 | 11 intervention, 16 placebo | Rifaximin (1200 mg/day) | Placebo | 2 | 3 |

| 151 | Furnari et al[85] | 2010 | 37 Rifaximin, 40 Rifaximin + partially hydrolyzed guar gum | Rifaximin (1200 mg/day) + partially hydrolyzed guar gum | Rifaximin | 34 | 23 |

| 152 | Lauritano et al[30] | 2009 | 71 intervention each group | Rifaximin (1200 mg/day) | Metronidazole (750 mg/day) | 45 | 31 |

| 153 | García-Cedillo et al[127] | 2024 | N/A | 400 mg Rifaximin-alpha every 8 hours for 2 weeks | N/A | 60% reported improvement in abdominal pain, 44% in bloating, 36% in flatulence, 60% in borborygmi, and 72% in stool consistency | A negative lactulose-Hydrogen Breath Test result for SIBO was documented in 32% of patients |

| 154 | Stefano et al[128] | 2000 | 10 intervention, 11 comparison | Rifaximin (1200 mg/day) | Chlortetracycline (999 mg/day) | 7 | 3 |

| 155 | Esposito et al[129] | 2007 | 73 | Rifaximin 1200 mg/day for 7 days | None | 19 patients with negative breath test | N/A |

| 156 | Zhao et al[130] | 2016 | 63 | Rifaximin | None | 45 patients with resolved SIBO | N/A |

| 157 | Zhuang et al[131] | 2018 | 30 IBS-D patients, 13 healthy controls | Rifaximin 400 mg twice daily for 2 weeks | Healthy controls | SIBO eradicated in 9/14 SIBO patients, significant GI symptom relief in all patients | N/A |

| 158 | Tocia et al[132] | 2021 | 44 | Rifaximin 1200 mg/day, 10 days/month for 3 months | Control group | 24 (Rifaximin), 9 (control) | 9 (Rifaximin), 9 (control) |

| 159 | Tocia et al[132] | 2021 | 44 | Rifaximin 1200 mg/day, 10 days/month for 3 months | Control group | 26 (Rifaximin), 8 (control) | 8 (Rifaximin), 8 (control) |

| 160 | Tocia et al[132] | 2021 | 44 | Rifaximin 1200 mg/day, 10 days/month for 3 months | Control group | 31 (Rifaximin), 9 (control) | 9 (Rifaximin), 9 (control) |

| 161 | Tocia et al[132] | 2021 | 44 | Rifaximin 1200 mg/day, 10 days/month for 3 months | Control group | 15 (Rifaximin), 6 (control) | 6 (Rifaximin), 6 (control) |

| 162 | Lee et al[133] | 2019 | 378 | Rifaximin | None | 0.6 kg weight gain in lowest body weight quartile group | N/A |

| 163 | Deng et al[134] | 2016 | 18 | Rifaximin (550 mg, 3 times daily for 10 days) | None | 6 patients (33.33%) turned negative for SIBO, improvement in GISS scores | N/A |

| 164 | Deng et al[134] | 2016 | 18 | Rifaximin (550 mg, 3 times daily for 10 days) | None | 6 patients showed significant improvement in diarrhea | N/A |

| 165 | Deng et al[134] | 2016 | 18 | Rifaximin (550 mg, 3 times daily for 10 days) | None | 6 patients showed improvement in abdominalgia | N/A |

| 166 | Deng et al[134] | 2016 | 18 | Rifaximin (550 mg, 3 times daily for 10 days) | None | 6 patients showed improvement in bloating | N/A |

| 167 | Deng et al[134] | 2016 | 18 | Rifaximin (550 mg, 3 times daily for 10 days) | None | 6 patients showed global improvement in GISS | N/A |

| 168 | Yoon et al[135] | 2018 | 51 | Rifaximin | None | 26 patients showed improvement | N/A |

| 169 | Schoenfeld et al[87] | 2014 | 95 | Rifaximin 275 mg twice daily for 2 weeks | Placebo | 13 | 9 |

| 170 | Schoenfeld et al[87] | 2014 | 190 | Rifaximin 550 mg twice daily for 2 weeks | Placebo | 29 | 15 |

| 171 | Schoenfeld et al[87] | 2014 | 96 | Rifaximin 550 mg twice daily for 4 weeks | Placebo | 9 | 7 |

| 172 | Schoenfeld et al[87] | 2014 | 624 | Rifaximin 550 mg three times daily for 2 weeks | Placebo | 68 | 32 |

| 173 | Schoenfeld et al[87] | 2014 | 98 | Rifaximin 1100 mg twice daily for 2 weeks | Placebo | 16 | 9 |

Across 18 Rifaximin studies, AEs were reported in 3 (16.7%)[22] compared to 2 of 12 Metronidazole studies (16.6%)[136,137] and 4 of 10 Bismuth studies (40%) (Table 3)[10,138,139]. Most AEs were mild gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, abdominal pain, dyspepsia). Serious AEs were rare (< 2% in all groups). Rifaximin’s tolerability was consistently superior, with no discontinuations reported due to AEs in any trial.

| Number | Ref. | Year of publication | Study design and setting | Number of patients enrolled with summary | Intervention used | Comparison used | Patients achieved outcome (intervention group) | Patients achieved outcome (comparison group) |

| 1 | Thazhath et al[139] | 2013 | Retrospective observational | 12 | CBS 120-480 mg/day | None | 7 | N/A |

| 2 | Thazhath et al[139] | 2013 | Retrospective observational | 4 | CBS 120-480 mg/day | None | 3 | N/A |

| 3 | Thazhath et al[139] | 2013 | Retrospective observational | 4 | CBS 120-480 mg/day | None | 2 | N/A |

| 4 | Thazhath et al[139] | 2013 | Retrospective observational | 5 | CBS 120-480 mg/day | None | 0 | N/A |

| 5 | Daghaghzadeh et al[140] | 2018 | Randomized controlled trial, clinical setting | 119 | Bismuth subcitrate 120 mg twice daily (before meals) | Placebo group (60 patients) | Pain severity reduced from 55 to 32, fewer days of pain, improvement in bloating and daily life | Pain severity reduced from 57 to 53, no significant change in pain days or bloating, no improvement in daily life |

No prespecified subgroup analysis was planned due to expected heterogeneity. Nevertheless, narrative stratification by IBS subtype indicated that Rifaximin was most effective in IBSD, with prominent relief of diarrhea and abdominal pain. In IBSC, Rifaximin’s benefits were less pronounced, and Metronidazole and Bismuth yielded modest symptom improvement. In IBSM, all three antibiotics provided comparable, intermediate relief.

This systematic review evaluated the efficacy of Metronidazole, Bismuth, and Rifaximin in treating SIBO and IBS.

Metronidazole has previously been described as an effective treatment to alleviate symptoms of patients with SIBO and IBS. Research reports considerable amounts of patients enjoying symptom relief, in particular by reducing inflammation and abdominal pain. In RCTs, Metronidazole showed significantly better symptom relief than placebo, thereby confir

Bismuth has also been reported as having a positive clinical effect mainly in ameliorating symptoms, such as abdominal pain and diarrhea. It has been shown to be effective to a substantial number of patients, although it is slightly less effective than Metronidazole. The safety profile of Bismuth is good with only mild pharmacodynamic effe

Rifaximin is, in general, the most efficient of the three antibiotics examined. It has demonstrated high effectiveness when employed in the management of symptoms including constipation, abdominal pain, and diarrhea, making it the preferred treatment option among most clinicians. Its superior effectiveness on Metronidazole and Bismuth is well-established, and a number of studies have demonstrated its effectiveness in delivering substantial relief symptoms. Rifaximin's good safety record distinguishes it from the two other antibiotics as it is accompanied by low adverse effects, thereby serving as a safe-and-efficacious drug for the treatment of SIBO and IBS[22].

Efficacy data for Metronidazole, Bismuth, and Rifaximin were pooled using a systematic review approach. This approach involved systematically gathering, assessing, and synthesizing data from various studies, while ensuring the inclusion of studies meeting predefined criteria. Compared to a meta-analysis which integrates data through statistical approaches, a systematic review aims at integrating the results between studies in order to give a qualitative perspective of the treat

Metronidazole: Metronidazole is generally well-tolerated by most patients. Mild side effects are reported most frequently, i.e., nausea, bitter taste and occasional dizziness. Although the side effects are typically transient, they may cause discomfort in some patients. Serious AEs are infrequent but may occur in a subset of patients. Metronidazole safety profile is, in general, good enough to allow it as a good treatment alternative, but the associated side effects could affect the compliance with the therapy in certain patients. Metronidazole was associated with AEs in 2 of 12 studies (16.6%).

Bismuth: Bismuth is known for its favorable safety profile. Side effects with a majority mild in nature and temporary generally include gastrointestinal symptoms such as blackening of stool. These side effects are, for the most part, not severe enough to interfere with treatment. Although less frequent, other mild side effects could happen, however, they do not usually necessitate its interruption of treatment. Because of Bismuth's broad safety profile, it is an appropriate therapy for most patients, especially those who could be poorly tolerated by alternative regimens. Nonetheless, prolonged administration of Bismuth compounds has been associated with rare neurotoxic effects and tissue accumulation, nece

Rifaximin: Rifaximin is reported to be the most well tolerated of the three antibiotics reviewed. Most of the patients develop only mild events such as gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea or flatulence. These side effects are usually mild and not sufficiently severe to cause treatment interruption. Serious AEs are very uncommon and help maintain Rifaximin's good safety record. Because of its tolerability and low side effect it is a first-choice option for most clinicians and patients. Rifaximin was associated with AEs in 3 of 18 studies (16.7%).

As summarized in the review, the safety profile overall of Metronidazole, Bismuth, and Rifaximin were well tolerated, with predominantly mild-to-moderate AEs. Metronidazole and Bismuth may warrant periodic monitoring to exclude uncommon but potentially serious gastrointestinal complications, whereas Rifaximin’s superior tolerability underpins its broad clinical adoption. Across the reviewed studies, side effects were generally transient and non-severe, reinforcing the suitability of these agents in SIBO and IBS management with a focus on patient comfort and adherence. Future research should aim to identify patient subgroups at elevated risk for antibiotic-related toxicity.

In this systematic review, subgroup analyses were conducted to determine the efficacy and risk-benefit profiles of Metronidazole, Bismuth, and Rifaximin for the treatment of IBS subtypes (IBS-D, IBS-C, IBS-M) and of varying severity of SIBO. These analyses helped to identify how different patient characteristics might influence treatment outcomes.

IBS-D: The three-antibiotic effectiveness was uniformly superior in IBS-D patients in the studies reviewed. Rifaximin was identified as the most potent treatment, which was associated with highly significant symptom relief, especially for diarrhea-related symptoms. Per studies, Bismuth and Metronidazole also provided slight, yet significant, relief for IBS-D participants, but less so than Rifaximin. In general, all 3 antibiotics significantly reduced IBS-D symptoms, with Rifaximin usually performing more effectively on all aspects. As the review describes, patients suffering from IBS-D appear reasonably responsive to such antibiotics, and in particular when adapted to their particular symptoms.

IBS-C: In the IBS-C patients, the antibiotics showed a slightly lower degree of efficacy. Rifaximin continued to be superior to the other antibiotics but with a lesser degree of effect than IBS-D. Bismuth and Metronidazole demonstrated moderate symptom relief, however their effectiveness was reduced in IBS-C compared with IBS-D patients and reduced further in IBS-C patients with the more severe constipation symptoms. This trend implies that IBS-C may pose further treatment complexities and that factors other than antibiotic response, such as gut microbiome, or motility problem, may influence antibiotic response. Nevertheless, all three of the antibiotics yielded some level of symptomatic relief, suggesting that all three of the antibiotics could be considered viable therapeutic options for the patients suffering from IBSC, especially in the absence of other therapeutic options.

IBS-M: For patients with IBS-M, the efficacy of the three antibiotics was more similar, with Rifaximin again showing the highest overall efficacy. Nonetheless, the strength of antibiotic difference was smaller in comparison with IBS-D or IBS-C subtypes. Bismuth followed as the second most effective antibiotic, while Metronidazole was the least effective in treating symptoms in this subgroup. The results of the reviewed studies indicated that, in IBS-M patients, use of antibiotics globally may be less effective, but through individualized therapeutic approaches, symptomatic relief may still be found. Mixed symptoms of IBS-M (diarrhea and constipation together) may need specific interventions or adjuvants to obtain the optimal results.

Mild SIBO: According to the review, all the 3 antibiotics were efficacious for the treatment of the mild SIBO. On the other hand, Rifaximin turned out to be most effective in the treatment of mild SIBO producing significantly more symptom relief in comparison with Bismuth and Metronidazole. The effectiveness of Bismuth and Metronidazole varied across studies, but both were found to be less effective than Rifaximin in mild SIBO cases. These results are in line with a hypothesis that Rifaximin could be the preferred drug in the treatment of SIBO, particularly in mild forms of SIBO, when, thanks to its narrow action in the small intestine, a greater therapeutic yield can be obtained.

Moderate to severe SIBO: It consistently outperformed Bismuth and Metronidazole in more complicated SIBO. Studies cited in this review showed that Rifaximin was more effective at improving symptoms for moderate to severe SIBO, by a greater number of visits with patients reporting symptom improvement. On the other hand, Bismuth and Metronidazole were shown to be substantially less effective in severe SIBO cases, with some reports of small or no symptom in patients with advanced SIBO. These findings indicate that for moderate to severe SIBO, Rifaximin should be considered as the treatment of first line because it has provided the most reliable and stable effects in eradicating symptoms.

According to the results of this systematic review, Rifaximin emerges as the primary treatment for SIBO and IBS—particularly for IBS-D and moderate to severe SIBO—owing to its consistent efficacy in alleviating symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloating, and bowel movement irregularity, coupled with a favorable safety profile and minimal transient side effects[21,40]. In instances where Rifaximin is contraindicated (e.g., due to hypersensitivity, significant liver dysfunction, or deleterious drug interactions) or when antibiotic resistance limits its effectiveness, alternative agents such as Bismuth and Metronidazole remain reasonable therapeutic options. Although both alternatives have demonstrated effectiveness in mitigating symptoms, especially in IBS-D and low-to-moderate SIBO, their broader antimicrobial spectra and higher incidence of side effects—such as the gastrointestinal disturbances and neurotoxicity associated with Metronidazole[8] and the comparatively modest efficacy of Bismuth[41]—restrict their long-term applicability.

The selection of an appropriate antibiotic regimen should incorporate clinical considerations such as IBS subtype, disease severity, treatment history, and patient-specific factors including symptom intensity, comorbidity, and personal preference[17]. Furthermore, adjunctive management strategies—such as prokinetic agents, dietary modifications, and fiber supplementation—may enhance therapeutic outcomes, particularly in patients with IBS-C or IBS-M who exhibit a diminished response to antibiotic monotherapy.

The systematic review also identifies several critical gaps in the current literature. Foremost, most studies have focused on short-term outcomes, leaving the long-term efficacy and safety of these antibiotics—along with their impact on the gut microbiome and the risk of developing antibiotic resistance—insufficiently characterized. For instance, while Rifaximin’s targeted, site-specific action minimizes systemic absorption and associated AEs[40], the potential for resistance and recurrence of symptoms (as seen with Metronidazole’s limited long-term utility[8]) warrants further investigation. Additionally, the heterogeneity of study designs, diagnostic criteria, and patient populations introduces variability that complicates the generalizability of the findings, underscoring the need for standardized, multicenter research across diverse geographic and clinical settings[21].

Mechanistic insights into how these antibiotics interact with the gut microbiota, modulate inflammatory pathways, and influence intestinal permeability and motility remain underexplored. Future research should aim to elucidate these molecular mechanisms and optimize dose regimens, treatment duration, and combination therapies. For example, combining Rifaximin with adjunctive agents—such as prebiotics, probiotics (e.g., compounds like VSL#3), or motility agents—may potentiate its clinical efficacy, particularly in patients who do not respond adequately to monotherapy[10,16,140].

Given the overlap in symptoms between IBS and other gastrointestinal conditions, a thorough differential diagnosis is essential before initiating antibiotic or adjunctive treatment strategies[141]. Disorders such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)[142-145], celiac disease[145,146], microscopic colitis[147], infectious etiologies including chronic bacterial[148-151] and parasitic infections[152-154], retained foreign bodies[155], small bowel and colonic neoplasms[156], nutritional deficiencies like pellagra[157], and drug-induced diarrhoea[158-160] can all mimic IBS symptomatology. Failure to differentiate these conditions can result in misdiagnosis, inappropriate antibiotic use, and delayed initiation of targeted therapies. Alarm features—such as unintentional weight loss, rectal bleeding, nocturnal symptoms, and a family history of colorectal cancer or IBD[161]—should prompt further evaluation through endoscopic, serologic, or stool-based testing. Accurate identification of the underlying pathology ensures optimal and safe management, avoiding ineffective or potentially harmful interventions that may complicate the clinical course.

This systematic review underscores the methodological strengths of the evidence synthesis, including a rigorous study selection, detailed data extraction, and informative subgroup analyses that clarify the relative efficacy and safety of Metronidazole, Bismuth, and Rifaximin. However, limitations such as publication bias, inconsistent reporting of AEs, and variable study quality temper the certainty of the conclusions. These issues highlight the need for high-quality, long-term research to validate current findings and guide more refined treatment strategies.

This systematic review highlights the comparative efficacy and safety profiles of Rifaximin, Metronidazole, and Bismuth in the management of SIBO and IBS. Rifaximin consistently demonstrated favorable outcomes, particularly in patients with IBS-D, due to its targeted action in the small intestine, minimal systemic absorption, and superior tolerability—supporting its role as the preferred first-line therapy. Metronidazole was effective, especially for SIBO, but its broader antimicrobial activity and higher incidence of gastrointestinal side effects may limit its long-term use. Bismuth also showed therapeutic potential, particularly when used in combination regimens; however, its role as a standalone agent remains less defined, and its long-term safety warrants caution due to the risk of neurotoxicity with prolonged use. While all three antibiotics offer viable treatment options, variability in study design, patient populations, and outcome measures suggests the need for an individualized treatment approach. Incorporating clinical presentation, microbiological factors, and patient tolerability is essential to optimize therapeutic outcomes. Future research should focus on long-term efficacy, comparative effectiveness, resistance development, and the identification of patient subgroups most likely to benefit from specific therapies to support more precise and sustainable treatment strategies.

We would like to sincerely thank the Gastroenterology MSc program at the Learna Ltd. in Association with University of South Wales for their invaluable assistance in our work. We acknowledge and commend the University of South Wales for their commitment to providing advanced problem-solving skills and life-long learning opportunities for healthcare professionals.

| 1. | Halfon P, Estrade JP, Penaranda G, Choucroun N, Bouaziz J, Nicolas-Boluda A, Retornaz F, Gurriet B, Plauzolles A. High prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth and intestinal methanogen overgrowth in endometriosis patients: A case-control study. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2025;170:284-291. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | Ghoshal UC. How to interpret hydrogen breath tests. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;17:312-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 142] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lenti MV, Hammer HF, Tacheci I, Burgos R, Schneider S, Foteini A, Derovs A, Keller J, Broekaert I, Arvanitakis M, Dumitrascu DL, Segarra-Cantón O, Krznarić Ž, Pokrotnieks J, Nunes G, Hammer J, Pironi L, Sonyi M, Sabo CM, Mendive J, Nicolau A, Dolinsek J, Kyselova D, Laterza L, Gasbarrini A, Surdea-Blaga T, Fonseca J, Lionis C, Corazza GR, Di Sabatino A. European Consensus on Malabsorption-UEG & SIGE, LGA, SPG, SRGH, CGS, ESPCG, EAGEN, ESPEN, and ESPGHAN: Part 2: Screening, Special Populations, Nutritional Goals, Supportive Care, Primary Care Perspective. United European Gastroenterol J. 2025;13:773-797. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rezaie A, Chang BW, de Freitas Germano J, Leite G, Mathur R, Houser K, Hosseini A, Brimberry D, Rashid M, Mehravar S, Villanueva-Millan MJ, Sanchez M, Weitsman S, Fajardo CM, Rivera IG, Joo L, Chan Y, Barlow GM, Pimentel M. Effect, Tolerability, and Safety of Exclusive Palatable Elemental Diet in Patients with Intestinal Microbial Overgrowth. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025;S1542-3565(25)00241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chang Y, Jung HS, Yun KE, Cho J, Cho YK, Ryu S. Cohort study of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, NAFLD fibrosis score, and the risk of incident diabetes in a Korean population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1861-1868. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Young RL, Lumsden AL, Keating DJ. Gut Serotonin Is a Regulator of Obesity and Metabolism. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:253-255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Pimentel M, Chow EJ, Lin HC. Normalization of lactulose breath testing correlates with symptom improvement in irritable bowel syndrome. a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:412-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Roland BC, Lee D, Miller LS, Vegesna A, Yolken R, Severance E, Prandovszky E, Zheng XE, Mullin GE. Obesity increases the risk of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO). Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | McNicholl AG, Molina-Infante J, Lucendo AJ, Calleja JL, Pérez-Aisa Á, Modolell I, Aldeguer X, Calafat M, Comino L, Ramas M, Callejo Á, Badiola C, Serra J, Gisbert JP. Probiotic supplementation with Lactobacillus plantarum and Pediococcus acidilactici for Helicobacter pylori therapy: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Helicobacter. 2018;23:e12529. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nyssen OP, Vaira D, Pérez Aísa Á, Rodrigo L, Castro-Fernandez M, Jonaitis L, Tepes B, Vologzhanina L, Caldas M, Lanas A, Lucendo AJ, Bujanda L, Ortuño J, Barrio J, Huguet JM, Voynovan I, Lasala JP, Sarsenbaeva AS, Fernandez-Salazar L, Molina-Infante J, Jurecic NB, Areia M, Gasbarrini A, Kupčinskas J, Bordin D, Marcos-Pinto R, Lerang F, Leja M, Buzas GM, Niv Y, Rokkas T, Phull P, Smith S, Shvets O, Venerito M, Milivojevic V, Simsek I, Lamy V, Bytzer P, Boyanova L, Kunovský L, Beglinger C, Doulberis M, Marlicz W, Goldis A, Tonkić A, Capelle L, Puig I, Megraud F, Morain CO, Gisbert JP; European Registry on Helicobacter pylori Management Hp-EuReg Investigators. Empirical Second-Line Therapy in 5000 Patients of the European Registry on Helicobacter pylori Management (Hp-EuReg). Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20:2243-2257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Lam CY, Palsson OS, Whitehead WE, Sperber AD, Tornblom H, Simren M, Aziz I. Rome IV Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders and Health Impairment in Subjects With Hypermobility Spectrum Disorders or Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:277-287.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Singh P, Lauwers GY, Garber JJ. Outcomes of Seropositive Patients With Marsh 1 Histology in Clinical Practice. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50:619-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ramai D, Lai JK, Ofori E, Linn S, Reddy M. Evaluation and Management of Premalignant Conditions of the Esophagus: A Systematic Survey of International Guidelines. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2019;53:627-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sookoian S, Pirola CJ. Letter: Mendelian randomisation to investigate moderate alcohol consumption in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; modest effects need large numbers-authors' reply. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:469-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Camilleri M. Diagnosis and Treatment of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Review. JAMA. 2021;325:865-877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 45.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rezaie A, Pimentel M, Rao SS. How to Test and Treat Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: an Evidence-Based Approach. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2016;18:8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Takakura W, Pimentel M. Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth and Irritable Bowel Syndrome - An Update. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Quigley EMM, Murray JA, Pimentel M. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth: Expert Review. Gastroenterology. 2020;159:1526-1532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Frissora CL, Cash BD. Review article: the role of antibiotics vs. conventional pharmacotherapy in treating symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1271-1281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Liébana-Castillo AR, Redondo-Cuevas L, Nicolás Á, Martín-Carbonell V, Sanchis L, Olivares A, Grau F, Ynfante M, Colmenares M, Molina ML, Lorente JR, Tomás H, Moreno N, Garayoa A, Jaén M, Mora M, Gonzalvo J, Molés JR, Díaz S, Sancho N, Sánchez E, Ortiz J, Gil-Guillén V, Cortés-Castell E, Cortés-Rizo X. Should We Treat SIBO Patients? Impact on Quality of Life and Response to Comprehensive Treatment: A Real-World Clinical Practice Study. Nutrients. 2025;17:1251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Stone JC, Leonardi-Bee J, Barker TH, Sears K, Klugar M, Munn Z, Aromataris E. Common tool structures and approaches to risk of bias assessment: implications for systematic reviewers. JBI Evid Synth. 2024;22:389-393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Castiglione F, Rispo A, Di Girolamo E, Cozzolino A, Manguso F, Grassia R, Mazzacca G. Antibiotic treatment of small bowel bacterial overgrowth in patients with Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18:1107-1112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Marie I, Ducrotté P, Denis P, Menard JF, Levesque H. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48:1314-1319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Feng X, Li XQ, Jiang Z. Prevalence and predictors of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in systemic sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40:3039-3051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Menees SB, Maneerattannaporn M, Kim HM, Chey WD. The efficacy and safety of rifaximin for the irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:28-35; quiz 36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in RCA: 204] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Mouillot T, Rhyman N, Gauthier C, Paris J, Lang AS, Lepers-Tassy S, Manfredi S, Lepage C, Leloup C, Jacquin-Piques A, Brindisi MC, Brondel L. Study of Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in a Cohort of Patients with Abdominal Symptoms Who Underwent Bariatric Surgery. Obes Surg. 2020;30:2331-2337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Tauber M, Avouac J, Benahmed A, Barbot L, Coustet B, Kahan A, Allanore Y. Prevalence and predictors of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in systemic sclerosis patients with gastrointestinal symptoms. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2014;32:S-82. [PubMed] |

| 28. | García-Collinot G, Madrigal-Santillán EO, Martínez-Bencomo MA, Carranza-Muleiro RA, Jara LJ, Vera-Lastra O, Montes-Cortes DH, Medina G, Cruz-Domínguez MP. Effectiveness of Saccharomyces boulardii and Metronidazole for Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth in Systemic Sclerosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65:1134-1143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Tahan S, Melli LC, Mello CS, Rodrigues MS, Bezerra Filho H, de Morais MB. Effectiveness of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and metronidazole in the treatment of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in children living in a slum. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;57:316-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Lauritano EC, Gabrielli M, Scarpellini E, Ojetti V, Roccarina D, Villita A, Fiore E, Flore R, Santoliquido A, Tondi P, Gasbarrini G, Ghirlanda G, Gasbarrini A. Antibiotic therapy in small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: rifaximin versus metronidazole. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2009;13:111-116. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Lauritano EC, Gabrielli M, Scarpellini E, Lupascu A, Novi M, Sottili S, Vitale G, Cesario V, Serricchio M, Cammarota G, Gasbarrini G, Gasbarrini A. Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth recurrence after antibiotic therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2031-2035. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Dear KL, Elia M, Hunter JO. Do interventions which reduce colonic bacterial fermentation improve symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome? Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:758-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Di Stefano M, Miceli E, Missanelli A, Mazzocchi S, Corazza GR. Absorbable vs. non-absorbable antibiotics in the treatment of small intestine bacterial overgrowth in patients with blind-loop syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:985-992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |