INTRODUCTION

Nocturia is often described as the most bothersome of all urinary symptoms and one of the most common. Nocturia was defined by the International Continence Society (ICS) in 2002 as a condition in which the patient wakes up ≥ 1 time during the night to urinate and each time causes interruption of sleep[1]. Nocturia affects approximately 25% of females and 20% of males in the general population and can severely impact the quality of life (QOL) of the population. Despite the relatively low prevalence of nocturia among young adults, this phenomenon shows a tendency to increase with age. In the older age group of 60 years and older, more than 70% of individuals report problems with nocturia, with more than one-third (36%) needing to get up to urinate two or more times per night[2,3]. A recent high-quality meta-analysis suggests that nocturia may be associated with an approximately 20% increased risk of falls, a 32% increased risk of fractures, and a 1.3-fold increased risk of death[4,5]. The International Consultation on Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (LUTS) in Men[6] classified nocturia into five categories based on its different pathophysiologic mechanisms: Increased total urine output, nocturnal polyuria (NP), decreased functional bladder capacity, sleep disorders, and mixed factors. It has a variety of potential etiologies, including physiologic and pathologic factors. Physiologic factors are usually seen in excessive nocturnal fluid intake, caffeine, alcohol, and high sodium diets; and medical disorders such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, peripheral edema, and organic changes in the urinary system are common etiologies[7,8]. This article summarizes the underlying pathophysiology of nocturia and updates a comprehensive diagnostic approach to nocturia in order to understand the etiology of the condition so that different therapeutic options can be selected.

Pathophysiology and classification of nocturia

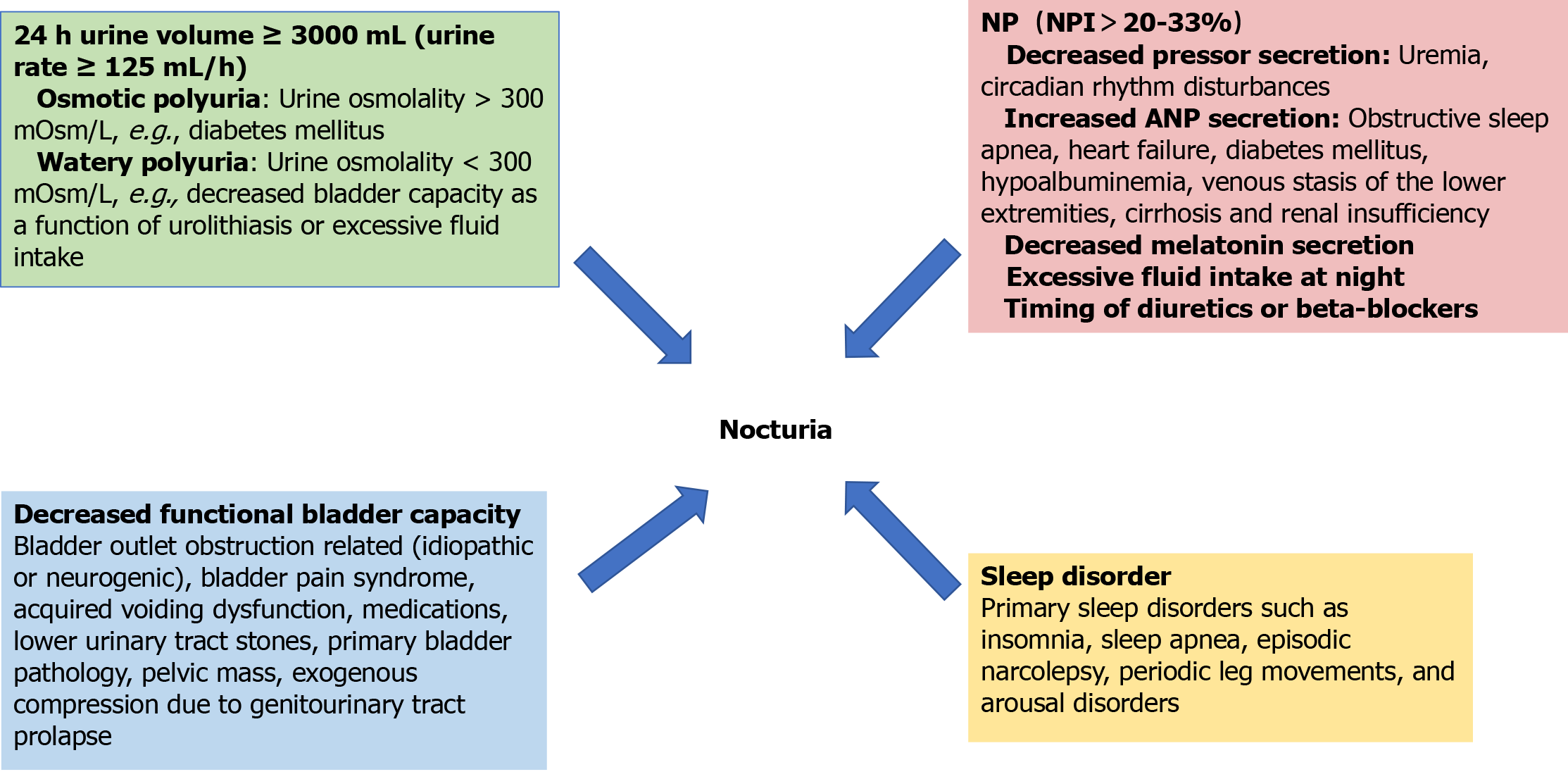

Nocturia is a multifactorial disorder caused by different mechanisms such as increased that have been comprehensively studied in terms of pathophysiology and are categorized as follows: Increased total urine output, NP, decreased functional bladder capacity, sleep disorders and confounding factors. Exploring these mechanisms is crucial for clarifying the root causes of disease and developing precise treatment strategies, and its core content covers the following key dimensions (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Aetiology of nocturia.

NP: Nocturnal polyuria; NPI: Nocturnal polyuria index; ANP: Atrial natriuretic peptide.

Increased total urine output: A 24-hour urine output of more than 3000 mL (urinary rate ≥ 125 mL/h) can be caused by osmotic polydipsia or aqueous polydipsia. Osmotic polydipsia is usually accompanied by a urine osmolality > 300 mOsm/L, as in diabetes mellitus, while aqueous polydipsia manifests itself as a urine osmolality < 300 mOsm/L and is seen in uremia or excessive fluid intake. Uremia can be caused by pressor deficiency (central) or renal resistance to pressor (nephrogenic), and common causes include brain injury and tubulointerstitial disease[9].

NP: NP is defined by ICS as nocturnal urine volume (NUV) greater than 20%-33% of the 24-hour urine volume (percentage adjusted for age)[1]. This percentage is referred to as the NP index (NPI). The normal value of the NPI ranges from 14% in young people to 34% in people over 65 years of age, and thus several thresholds have been proposed. Other definitions of NP have been proposed, such as NUV > 6.4 mL/kg, NUV > 0.9 mL/min, or NUV > 90 mL/h[10,11]. Nocturia is mainly regulated by two hormones: antidiuretic hormone (pressor) and atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP). Among them, the secretion level of antidiuretic hormone is regulated by both plasma osmolality and body fluid volume, and its main physiologic function is to promote water reabsorption in the renal collecting ducts. Urine dilution may be triggered when certain pathological conditions (e.g., uremia) interfere with the normal secretion of antidiuretic hormone or affect renal sensitivity to it. Pressurin secretion fluctuates naturally between day and night, with healthy individuals experiencing peaks in pressurin levels at night, whereas patients with NP lack this nocturnal elevation of pressurin. In addition, individuals who do not suffer from insomnia usually have higher levels of nocturnal melatonin secretion than insomnia patients[9,12,13]. On the other hand, disorders like obstructive sleep apnea that cause obstruction of the upper airway are able to stimulate the release of cardiac natriuretic hormone from the atria and ventricles by increasing the negative pressure in the thoracic cavity and facilitating the flow of more venous blood to the heart. ANP further exacerbates NP by inhibiting the secretion of pressurizing hormone and decreasing the reabsorption of sodium. Congestive heart failure is also a common cause of elevated ANP levels and subsequent NP[13]. In addition, diseases such as diabetes mellitus, hypoalbuminemia, venous stasis of the lower extremities, cirrhosis, and renal insufficiency can trigger peripheral edema and increase renal burden due to the transfer of fluids from the interstitium to the vasculature while the patient is at bed rest, leading to nocturia. Lifestyle factors, such as excessive intake of salt, fluids, alcohol, or caffeine at night, are also a common cause of NP. Finally, the timing of diuretics or beta-blockers may also influence the increase in nocturnal urine output[14].

Decreased functional bladder capacity: The reasons for this condition of the bladder are multiple: Significant postvoid residual urine due to decreased bladder contractility, usually associated with associated bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) caused by benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), detrusor overactivity (DO) [idiopathic (usually concurrent with BPH) or neurogenic], bladder pain syndrome, acquired voiding dysfunction, medications, lower urinary tract stones, primary bladder pathology resulting in reduced anatomical capacity, or exogenous compression due to pelvic mass or genitourinary tract prolapse[10,15,16].

Sleep disorders: Primary sleep disorders such as insomnia, sleep apnea, episodic narcolepsy, periodic leg movements, and arousal disorders can cause nocturia. Heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), endocrine disorders, and neurological disorders can also cause sleep disorders, leading to nocturia.

Mixed factors: Including the above reasons, commonly found in the elderly, combined cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases and patients taking related drugs.

Diagnosis of nocturia

Nocturia requires a combination of diagnostic methods to further define the pathophysiology of nocturia in each patient, making the diagnostic approach particularly important and consisting of the following four components: History taking, physical examination, supporting diagnostic scales, and ancillary tests.

Medical history enquiry: Thorough history taking can help the clinician better determine the underlying etiology of nocturia and develop an appropriate treatment plan. The history inquiry should include several areas. First, LUTS are a key component of the nocturia workup, and nocturia frequency, daytime LUTS, and voiding rhythm should be assessed by 24-hour frequency-volume chart (FVC) or a bladder diary, during which the patient should be questioned about his or her lifestyle habits, including daily fluid intake[17], alcohol intake, caffeine intake (especially at night or near bedtime), dietary sodium intake[18] and the presence of sleep disorders. The high prevalence of nocturia in the elderly population is closely related to a variety of underlying diseases and long-term medication use. There are various etiologies that trigger nocturia symptoms, such as cardiovascular diseases (congestive heart failure), respiratory diseases (obstructive sleep apnea, asthma, COPD), endocrine-metabolic diseases (diabetes mellitus, thyroid dysfunction), neurological disorders (Parkinson's disease, dementia), genitourinary disorders (uterine prolapse), and other sleep-related disorders (rapid eye movements, sleep behavior disorders, restless legs syndrome, episodic sleep disorders)[16]. In addition, disturbances in the secretion of key hormones that regulate fluid and electrolyte balance (e.g., antidiuretic hormone and ANP) can lead to NP[19,20]. In terms of pharmacologic factors, medications that may cause fluid retention (e.g., nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), calcium channel blockers, glucocorticoids, thiazolidinediones hypoglycemic agents, pramipexole, and gabapentin), as well as diuretics taken at bedtime, may induce or exacerbate nocturia symptoms.

Physical examination: In addition to routine checkups, the consensus recommends focusing on the following examinations, such as weight, waist circumference and blood pressure; cardiac and respiratory examinations; foot and ankle examination of the lower extremities for edema; palpation of the suprapubic area for urinary retention; rectal examination of the prostate gland for male patients, and pelvic floor examination of the pelvic floor for uterine prolapse and other gynecological disorders for female patients.

Auxiliary diagnostic scales

As an important tool for the diagnosis of nocturia, 24-hour FVC measures and records the volume and time of each urination during the day and night for 3 consecutive days, combined with the following parameters:

NUV: The total amount of urine voided each night, including the first urination in the morning.

Nocturnal urine output: From the time you go to sleep to the time you wake up in the morning; the first morning urination is not counted as nocturnal urine output.

NPI: Which refers to the proportion of nocturnal urine output in 24-hour urine output, NPI = NUV/24 h urine output × 100%.

Nocturia index: The proportion of nocturnal urine output to maximum urine output, Nocturia index (Ni) = nocturnal urine output/maximum urine output.

Predicted number of nocturnal voids: Predicted number of nocturnal voids (PNV) = Ni-1; actual number of nocturnal voids (ANV).

Nocturnal bladder capacity index: Nocturnal bladder capacity index (NBCI) = ANV-PNV.

Polyuria was diagnosed when the 24-h urine volume was > 40 mL/kg; NP was diagnosed when NP was > 33% (≥ 65 years), > 25% (> 35 years and < 65 years), or > 20% (≤ 35 years); and nocturnal bladder capacity reduction was diagnosed if the NUV was less than the maximal bladder capacity, and diagnosis was made by applying NBCI. When ANV exceeds PNV, an NBCI > 0 indicates reduced nocturnal bladder capacity relative to the patient's maximum 24-hour capacity[21,22]. Patients who meet the criteria for polyuria should be identified with volumetric polydipsia (e.g., diabetes mellitus) or urolithiasis. Patients with suspected sleep disorders should undergo further sleep-related examinations, such as sleep duration, nighttime wakefulness, nighttime sleep quality, the time of the first sleep cycle (the time between sleep and the first awakening to urinate), and other special examinations such as sleep electroencephalography, etc., if necessary.

In addition, the Overactive bladder Symptom Score (OABSS) and the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) were used to assess concomitant LUTS in patients with nocturia; QOL was assessed using the Perceived Bladder Condition Scale (PPBC), the Nocturia QOL Questionnaire, and the International Counseling Incontinence Questionnaire; and sleep disorders were assessed with the Berlin Questionnaire Survey, the First Uninterrupted Sleep Period (FUSP) questionnaire[21,23]. FUSP questionnaire to assess sleep disorders[21,23], and sleep polysomnography to assist in the diagnosis of sleep-related disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea.

Auxiliary examination

Laboratory tests: On the basis of routine tests (urine routine, urine culture, liver and kidney function, blood glucose, blood electrolytes), monitor changes in blood and urine osmolality. Normal human plasma arginine vasopressin is 2.3-7.4 pmol/L.

Imaging: Ultrasonography of the urinary tract is preferred, and CT and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the urinary tract may be performed if the results are abnormal. Voiding cystourethrography can be used to assist in the diagnosis of primary bladder neck obstruction, but is not suitable for assessing the severity of urinary symptoms[24]. MRI of the head may assist in the diagnosis of urolithiasis secondary to neurological disorders such as suprasellar tumors. Cardiovascular ultrasound can assist in the diagnosis of cardiovascular disease, such as nocturia due to congestive heart failure.

Urological examination: for those who have difficulty in urination, urinary flow rate, residual urine and other tests, invasive urodynamic examination if necessary, and cystoscopy if necessary to exclude bladder tumors or stones and other organic lesions.

The latest European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines on non-neurogenic LUTS state that in the diagnosis of nocturia in men[25] a detailed history is mandatory, a bladder diary or FVC is particularly helpful, followed by a review of behavioral factors affecting fluids and sleep, and a detailed questioning of the patient's history of other illnesses and medications, which states that the IPSS is an assessment of the comprehensive range of symptoms of the prostate, and that although the questionnaires are well established and widely used in urology, the limitation is his inability to accurately assess the distress caused by each individual symptom, including nocturia. The EAU guidelines recommend the use of validated symptom-scoring questionnaires, and a number of questionnaires that are sensitive to symptomatic changes have been developed and can be used to monitor treatment. Symptom scores help to quantify LUTS. In diagnosing nocturia in women[26], a thorough medical history is an integral part of the assessment of women with nocturia, including screening for sleep disturbances. In addition to a bladder diary, tests for renal function, thyroid function, glycosylated hemoglobin, and serum calcium levels need to be considered.

The latest ICS guidelines point to the following diagnostic strategies[17]: bladder diary consensus, but there is no consensus at the moment on its duration (3 days is recommended). Diary consensus on sleep, intake (fluids and food), and physical activity, the need to check blood pressure and edema, and, if necessary, PSA, serum sodium screening (SSC), renal/cardiac function and endocrine screening, as well as pelvic (in women) or rectal examination (in men) screening, the timing or fasting at the time of the SSC execution does not matter. The ICS guideline also proposes a widely used and validated patient-completed questionnaire, the International Consultation on Urinary Incontinence Questionnaire for Men with LUTS, which includes incontinence problems and disturbs for each symptom. It contains 13 items, including subscales for nocturia and OAB.

Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of nocturia is very important and more and more questionnaires and diagnostic methods are being proposed, FVC, bladder diary of 3 days and more, factors affecting fluids and sleep, history of disease and medication history reached consensus but questionnaires did not, this is a direction for further research in the future.

TREATMENT AND MANAGEMENT STRATEGIES FOR NOCTURIA

Based on the specific pathophysiology of nocturia in each patient, appropriate treatments are required to achieve effective relief of nocturia, and there is growing evidence of the effectiveness of pharmacological treatments in addition to lifestyle guidance and behavioral treatments, with the current status of treatments for each of the different interventions indicated below.

Lifestyle guidance and behavioral therapy

Drinking water related guidance: The first line of treatment to change urinary symptoms is recommended to be behavioral therapy, focusing on suspected underlying causes. Lifestyle changes are important, including limiting fluid intake: About 100 ounces of fluid per day for healthy men and 70 ounces per day for women. Fluid intake varies by age, with 45 to 60 ounces of caffeine-free beverages per day recommended for older adults. It is recommended that daily fluid intake should be rationally distributed throughout the day and strictly controlled within 3-4 hours before bedtime, with a particular need to avoid alcoholic and caffeinated beverages. In terms of lifestyle and dietary management, a healthy dietary pattern is recommended, in which daily sodium intake should be limited to 8 grams[27,28]. In non-randomized controlled trial (RCT) studies, high dietary sodium intake increased nocturia[29], which was further supported by observations from an observational study[18]. High dietary intake of fruits and vegetables was shown to be associated with nocturia, while high intake of tea was associated with nocturia in observational studies. In patients with leg edema, wearing compression stockings and leg elevation before going to bed can reduce edema, which in turn reduces nocturnal fluid flow and thus NP[30]. Sleep-related modifications can also help to manage urinary symptoms, as shown in a recent RCT of sleep behavioral interventions for patients with nocturia[31]. Over the 14-day assessment period, total nocturnal urination decreased by 6.5 ± 4.8 in the brief behavioral therapy for insomnia (BBTI) group and increased by 1.3 ± 7.3 in the information control (IC) group (P = 0.04, effect size 0.82), which suggests that patients follow the principles of BBTI for insomnia, which include reducing bedtime, waking up at the same time each day, going to bed only when sleepy, and staying in bed only when asleep.

Exercise therapy: Pelvic floor muscle function training as a non-pharmacological intervention can effectively improve the related symptoms. The specific training method is as follows: patients are instructed to consciously contract the pelvic floor muscle groups while relaxing the abdominal muscle groups for 2-10 seconds each time, and the total number of daily training is not less than 45 times. As the training continues, the duration of each contraction should be gradually extended[32]. Exercising the pelvic floor muscles may strengthen urethral control on the one hand, and also contribute to the reestablishment of inhibitory neural pathways during the storage phase, which in turn improves urinary frequency and urgency symptoms.

There are few RCTs of behavioral measures for nocturia as a primary outcome. Lifestyle-based guidance and behavioral treatments do not involve the use of medications and have no side effects on humans, and more behavioral treatments for nocturia need to be invested in clinical studies for nocturia in the future in order to provide sufficient evidence for it.

Treatment of BOO

Some studies have shown that the most common etiology causing BOO in men is prostate obstruction caused by BPH[33], which causes a series of LUTS, and nocturia is a part of its LUTS, and its treatment options have been recommended by domestic and international guidelines or consensus[34], regarding the pharmacological treatment of BPH-related nocturia in men with BPH However, the latest guidelines or consensus at home and abroad list α1 receptor blockers as first-line or preferred drugs, which can be used alone or in combination with 5α-reductase inhibitors, but their common adverse effects (postural hypotension) are prone to cause falls in the elderly and even induce cardiovascular and cerebral vascular events, and highly selective α-blockers (e.g., tamsulosin) have a weak affinity for the α1B receptor, and compared with other α1-blocking agents, the incidence of hypotension related adverse effects have a lower incidence and a relatively high safety profile[33]. However, a high-quality meta-analysis by the EAU[34] pointed out that the evidence for alpha1 receptor blockers in the treatment of nocturia derived from the majority of clinical studies that included nocturia as a secondary outcome while failing to identify and exclude patients with coexisting NPs was not sufficient. Patients with BPH who have moderate to severe LUTS and have significantly affected their QOL may choose surgery and minimally invasive treatment, especially those who have poor results from medication or who refuse to accept medication, and refer to the relevant Western medical guidelines for the surgical approach, among others.

Treatment of OAB syndrome

OAB is defined as a syndrome of storage symptoms characterized by urinary urgency, with or without urge incontinence, with frequent nocturia, the etiology of which is unclear, and although all theories relate to the term “DO”, not all patients with OAB suffer from DO, which has been confirmed in only about 50% of cases[35].

Currently, cholinergic receptor antagonists and adrenergic beta agonists are still the mainstay of first-line pharmacological treatment. Cholinergic receptor antagonists (tolterodine, solifenacin) have been shown to significantly improve symptoms and QOL, but the main problem with these drugs is that the muscarinic receptors on which they act are found in many of the organs of the body, which leads to the occurrence of many common side effects: Dryness of the mucous membranes (dry mouth, eyes , vaginal dryness), constipation, palpitations, arrhythmias, tachycardia and cognitive disturbances (somnolence, hallucinations, confusion, delirium, blurred vision, memory problems) or urinary retention[36], which leads to poor compliance and inability of patients to regulate their treatment in the long term. Of the three β-adrenergic receptors present in the bladder, findings have shown that β3 is the main one and is responsible for the relaxation of the forcing muscle during the filling phase[36,37]. β3 receptor agonists (mirabolone) are comparable in effectiveness to anti-muscarinic drugs, but have fewer side effects, resulting in greater patient compliance, and in patients refractory to monotherapy, cholinergic receptor antagonists may be used in conjunction with mirabolone, with outcomes superior to those of monotherapy[35,38].

For refractory OAB (where behavioral control combined with pharmacotherapy is ineffective), intravesical injection of botulinum toxin type A (OBTA) temporary bladder detrusor chemical denervation, posterior tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS), and Sacral Nerve Stimulation (SNS) are often used, all three of which have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2013, 2005, and 1997, and also recommended by ICS for SNS and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation as second-line treatment options for refractory OAB. However, while OBTA improves OAB symptoms, the risk of increased postvoid residual urine volume and symptomatic urinary retention, clean intermittent self-catheterization with urinary tract infections is significant[39-41], and questions remain regarding optimal administration of botulinum toxin A in OAB patients as well as post-treatment tolerability[39,40]. Neurostimulation modulation therapies such as PTNS and SNS have been a validated and widely used treatment option for lower urinary tract dysfunction for decades, and a wearable, smartphone-controlled, rechargeable percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (TTNS) device has emerged in recent years, which offers a more convenient and easier-to-maintain treatment modality for patients with OAB[42,43]. Currently available nerve stimulation techniques vary from very low invasive treatments to more highly invasive treatments requiring delicate surgery. Some experimental techniques look promising, but follow-up studies in larger cohorts to determine efficacy are lacking. The high incidence of treatment-related adverse events (AEs) has prevented their wider use[39,40,44,45].

In terms of surgical treatment, some studies have reported treating OAB by surgery, and the main surgical modalities include bladder enlargement, bladder denervation control, forced urethrotomy, and even total cystectomy. However, due to the permanent damage caused by surgery, its long-term outcome and complications are of concern. Therefore, surgical approaches should be used with caution and should only be considered in patients with OAB who have failed to respond to all of the above.

Treatment with desmopressin

Desmopressin acetate has been widely used in the treatment of urosepsis and nocturia since its introduction to the market in 1974, and it is a human-synthesized antidiuretic hormone analog commonly used in clinical practice, and a large number of clinical studies have demonstrated the efficacy of desmopressin acetate in the treatment of nocturia[46]. Antidiuretic hormone regulates the total fluid volume and osmotic balance in the body. Elevated plasma osmolality stimulates the pituitary gland to secrete arginine antidiuretic hormone, which promotes renal reabsorption of water and reduces urine output. Desmopressin can mimic the binding of arginine antidiuretic hormone to V2 receptors on the distal renal collecting tubules to concentrate urine and reduce total urine output[47]. Although many clinical studies have demonstrated that desmopressin is effective in reducing the severity of nocturia while improving patients' QOL. A new formulation suggests that a minimum dose of 25 μg of oral sublingual desmopressin appears to be ideal for women, while men usually benefit from at least 50 μg[48]. However, the safety of desmopressin is critical to its clinical use. Only a few clinical trials of long-term use of desmopressin have been reported[49-51], and it is noteworthy that the drug is also associated with a variety of adverse effects such as abdominal pain, headache, insomnia, and hyponatremia. Among them, hyponatremia is the only serious complication associated with the drug, and the risk of hyponatremia increases with age. The conclusions of these long-term clinical studies are inconsistent, and the incidence of adverse reactions varies significantly. The occurrence of adverse reactions is mostly related to the patient's age, gender, basal blood sodium concentration, renal functional status, hemoglobin level, and cardiac functional status[52].

Female, elderly patients with low basal sodium concentration have a higher incidence of hyponatremia and should be used with caution[47]. Early monitoring of blood sodium concentration is recommended, starting on the third day of administration, once a week for 2 weeks, and then periodically reviewed every 1-2 months; if the blood sodium concentration is lower than the range of normal values, it is recommended that the drug be discontinued, and most of the adverse effects can be alleviated or disappeared on their own after the discontinuation of the drug[50,53]. Between the high sustained use of desmopressin as well as its efficacy, adjusting the dosage according to the patient's gender and age in the clinic may improve the therapeutic window and minimize the risk of hyponatremia without compromising clinical efficacy. Additional long-term safety studies of desmopressin in patients with nocturia of different ages and gender are still lacking.

Melatonin

Melatonin, as an endogenous hormone, is mainly secreted by the pineal gland and is able to regulate circadian rhythms and the sleep-wake cycle. Melatonin secretion is increased in darkness and inhibited by light, a process regulated by the supraoptic nucleus of the hypothalamus[54]. In recent years, studies on melatonin in the treatment of nocturia have gradually increased. Animal model studies have shown that melatonin, as an endogenous hormone, has an inhibitory effect on the contractility of mammalian bladder smooth muscle[55], as well as improves nocturnal bladder capacity and reduces nocturnal urine output[56,57]; however, melatonin may have different effects on humans and animals, and there are now a growing number of clinical trials that demonstrate that 2 mg melatonin is a safe and effective therapeutic method[58-60], especially in BPH, women and elderly patients. only by reducing the number of nocturnal voiding episodes without affecting bladder capacity or nocturnal urine output. In addition, nocturnal serum melatonin levels are lower in older adults with nocturia than in those without nocturia[61]. Documented side effects include decreased body temperature, sedation, dizziness and headache, depression, tachycardia, and pruritus[58].

Melatonin has been shown to be effective in the treatment of nocturia, but the therapeutic mechanism is not clear, and the following studies are available: (1) Melatonin increases bladder capacity and reduces urine output via γ-aminobutyric acid A receptors in the brain[61]; (2) Inhibitory effects on contractility of the detrusor muscle (directly through intracellular mechanisms)[62-65]; (3) Inhibitory effect on bladder afferents (via MT2 receptors expressed on the bladder of low-threshold stretch-sensitive muscle mucosa)[64]; (4) Prevention of age-related changes in bladder contractility due to its potent antioxidant effects[65]. More studies in animals are needed to fully validate the proposed multiple mechanisms of action of melatonin to ameliorate nocturia.

Traditional Chinese medicine

Currently, due to the limited efficacy, low durability, and high incidence of AE of OAB treatments, clinicians in Asia commonly use traditional Chinese medicine as an alternative to OAB treatment, such as acupuncture and acupressure. In recent years, more and more clinical studies and experimental data have supported the effectiveness of traditional Chinese medicine in the treatment of OAB. Some modern studies have shown that acupoint patches can be more effective in relieving OAB symptoms, with significant effects in improving the OABSS, Urinary Urgency Severity Scale, and PPBC[66,67]. Meanwhile, the side effects of acupressure are relatively small and can be used in combination with western medicines to achieve better therapeutic effects. Tang et al[67] showed that cinnamon (Cinnamomum cassia) and cinnamaldehyde, the main components of acupressure, inhibited the inflammatory and fibrotic signals in cyclophosphamide-induced OAB disease in mice. Shen et al[68] pointed out that electroacupuncture, whose mechanism is similar to that of SNM, can be utilized to assess the therapeutic effects of SNM, thus providing a reference for patients and clinicians to determine whether SNM treatment is effective. Although these studies did not use nocturia symptoms as the primary endpoint, they provide a new strategy for clinical treatment of nocturia.

Other medication

Some studies have shown that diuretics can be used as a second-line treatment option for nocturia. Diuretics have an onset of effect at 2 h after administration, peak at 4-6 hour, and last for 6-12 hour[69] Commonly used diuretics include hydrochlorothiazide and furosemide, which are recommended for use in the morning. NSAIDs are effective in the treatment of patients with refractory nocturia associated with BPH[70], commonly used NSAIDs include celecoxib and loxoprofen. Studies on the use of these drugs in the treatment of nocturia are few and far between, and more research is needed to prove their efficacy and safety.

CONCLUSION

Nocturia has been comprehensively studied as a pathological condition that severely affects patients' QOL, and its management strategy depends on the underlying mechanisms. Currently, with more exploration of the pathogenesis of nocturia, the multifactorial etiology of nocturia is becoming clearer, and the different etiologies require the selection of appropriate treatments to improve the patient's condition faster and better, which suggests the need for standard diagnostic strategies, which are not currently available, except for detailed history taking, bladder diaries, FVC, factors affecting fluids and sleep, history of illness, and history of medications, which have reached a consensus in all modern guidelines , neither the choice of questionnaire nor other diagnostic strategies have reached consensus. Behavior modification remains the first line of treatment, pharmacological modalities are becoming more abundant, but pharmacological treatments are associated with adverse effects and a lack of extensive long-term clinical trials; the increased risk of hyponatremia associated with desmopressin has been debated; the evidence for the effectiveness of melatonin is becoming more extensive but still lacks a clear mechanism of action; and more advanced therapeutic techniques, such as TTNS, are appearing for BOO and OAB in addition to initial pharmacological treatments. technologies, such as TTNS, which require future follow-up studies in larger cohorts to determine efficacy; the better efficacy and fewer adverse effects of Chinese medicine in the treatment of OAB are its strengths, such as acupressure and electro-acupuncture, but there is less evidence of its clinical efficacy and the mechanism of action is unclear, further evidence is needed. Although the treatment modalities are not comprehensive enough, this provides a large number of directions for individualized therapeutic management. Our goal is to make it easier for clinicians to diagnose and treat nocturia and to shorten the nocturia journey for patients. Further research is necessary to reach a consensus on diagnostic and treatment algorithms for nocturia based on underlying mechanisms, to standardize the diagnosis and to improve the management of nocturia.