Published online Jun 20, 2023. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v13.i3.142

Peer-review started: January 18, 2023

First decision: April 20, 2023

Revised: April 22, 2023

Accepted: May 24, 2023

Article in press: May 24, 2023

Published online: June 20, 2023

Processing time: 153 Days and 1.8 Hours

The evidence on preferences for oral- vs blood-based human immunodeficiency virus self-testing (HIVST) has been heterogenous and inconclusive. In addition, most evaluations have relied on hypothetical or stated use cases using discreet choice experiments rather than actual preferences among experienced users, which are more objective and critical for the understanding of product uptake. Direct head-to-head comparison of consumer preferences for oral- versus blood-based HIVST is lacking.

To examine the existing literature on preferences for oral- vs blood-based HIVST, determine the factors that impact these preferences, and assess the potential implications for HIVST programs.

Databases such as PubMed, Medline, Google Scholar, and Web of Science were searched for articles published between January 2011 to October 2022. Articles must address preferences for oral- vs blood-based HIVST. The study used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses checklist to ensure the quality of the study.

The initial search revealed 2424 records, of which 8 studies were finally included in the scoping review. Pooled preference for blood-based HIVST was 48.8% (9%-78.6%), whereas pooled preference for oral HIVST was 59.8% (34.2%-91%) across all studies. However, for male-specific studies, the preference for blood-based HIVST (58%-65.6%) was higher than that for oral (34.2%-41%). The four studies that reported a higher preference for blood-based HIVST were in men. Participants considered blood-based HIVST to be more accurate and rapid, while those with a higher preference for oral HIVST did so because these were considered non-invasive and easy to use.

Consistently in the literature, men preferred blood-based HIVST over oral HIVST due to higher risk perception and desire for a test that provides higher accuracy coupled with rapidity, autonomy, privacy, and confidentiality, whereas those with a higher preference for oral HIVST did so because these were considered non-invasive and easy to use. Misinformation and distrust need to be addressed through promotional messaging to maximize the diversity of this new biomedical technology.

Core Tip: We conducted a scoping review of the literature to determine the preferences for oral- vs blood-based human immunodeficiency virus self-testing (HIVST) and related factors. We searched PubMed, Medline, Google Scholar, and Web of Science databases for articles published between January 2011 and October 2022 that addressed preferences for oral- vs blood-based HIVST. The pooled preferences for blood- and oral-based HIVST were 48.8% and 59.8%, respectively. For male-specific studies, the preference for blood-based HIVST was higher than for oral. These results highlight the need to address misinformation and distrust through promotional messaging to maximize the diversity of this new biomedical technology.

- Citation: Adepoju VA, Imoyera W, Onoja AJ. Preferences for oral- vs blood-based human immunodeficiency virus self-testing: A scoping review of the literature. World J Methodol 2023; 13(3): 142-152

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v13/i3/142.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v13.i3.142

The Joint United Nations Programme on human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) (UNAIDS) has set 95:95:95 as a strategy to end HIV/AIDS by 2030. Although much progress has been made in achievement of the first 95 (i.e. 95% of individuals with HIV should test and know their HIV status), progress has been slow among hard-to-reach populations such as men, key populations, adolescents, and young persons. Men living with HIV perform less than women, with only 82% of men living with HIV knowing their HIV status[1]. Compared to women living with HIV, there are 740000 more men living with HIV who do not know their HIV status, 1.3 million more men who are not on treatment, and 920000 more men who are not virally suppressed[2]. The World Health Organization (WHO) released the first normative guideline on HIV self-testing (HIVST) in 2016[3]. WHO recommended HIVST as an additional approach to HIV testing services and recently added that both oral- and blood-based options should be provided. HIVST is safe, private, confidential, and convenient with the potential to improve access to testing for hard-to-reach populations such as men, adolescents, and young people as well as key populations. ST, being the first step in the care continuum, presents an enormous opportunity to close the HIV testing gap and achieve the global 95:95:95 fast track target set by UNAIDS. Self-testing empowers consumers to control when, where, and how they test for any of these diseases. Given the challenges in accessing traditional, provider-led testing services such as long distance from facilities, limited operating hours of conventional clinics, competing client priorities such as job and schooling, stigma, high cost, poor awareness, and dearth of culturally competent healthcare workers[4,5], ST as an alternative testing model, is a useful tool to expand access to testing for HIV, especially among vulnerable groups.

As of August 2022, six HIVST have been prequalified by the WHO (one using oral fluid and five using whole blood), i.e. Wondfo, Mylan, Insti, Check Now, Sure Check, and OraQuick[6,7]. However, evidence on preferences for oral- vs blood-based options has been heterogenous and inconclusive[8,9]. In addition, most evaluations have relied on hypothetical or stated use cases using discreet choice experiments[10,11] rather than actual use preferences from experienced end-users, which are more objective and critical for uptake. Two main types of HIVST are available: oral- and blood-based tests. While both tests have demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity, the preferences of individuals for one test type over the other remain unclear. Understanding these preferences is crucial to promoting the widespread adoption and usage of HIVST.

The purpose of this scoping review is to provide a comprehensive overview of the literature on preferences for oral- vs blood-based HIVST, identify factors influencing these preferences, and explore the implications of these preferences for the promotion and implementation of HIVST programs. By synthesizing existing evidence, this review aims to inform policy-makers, healthcare providers, and other stakeholders involved in the design and implementation of HIVST programs, in order to maximize uptake and improve overall public health outcomes.

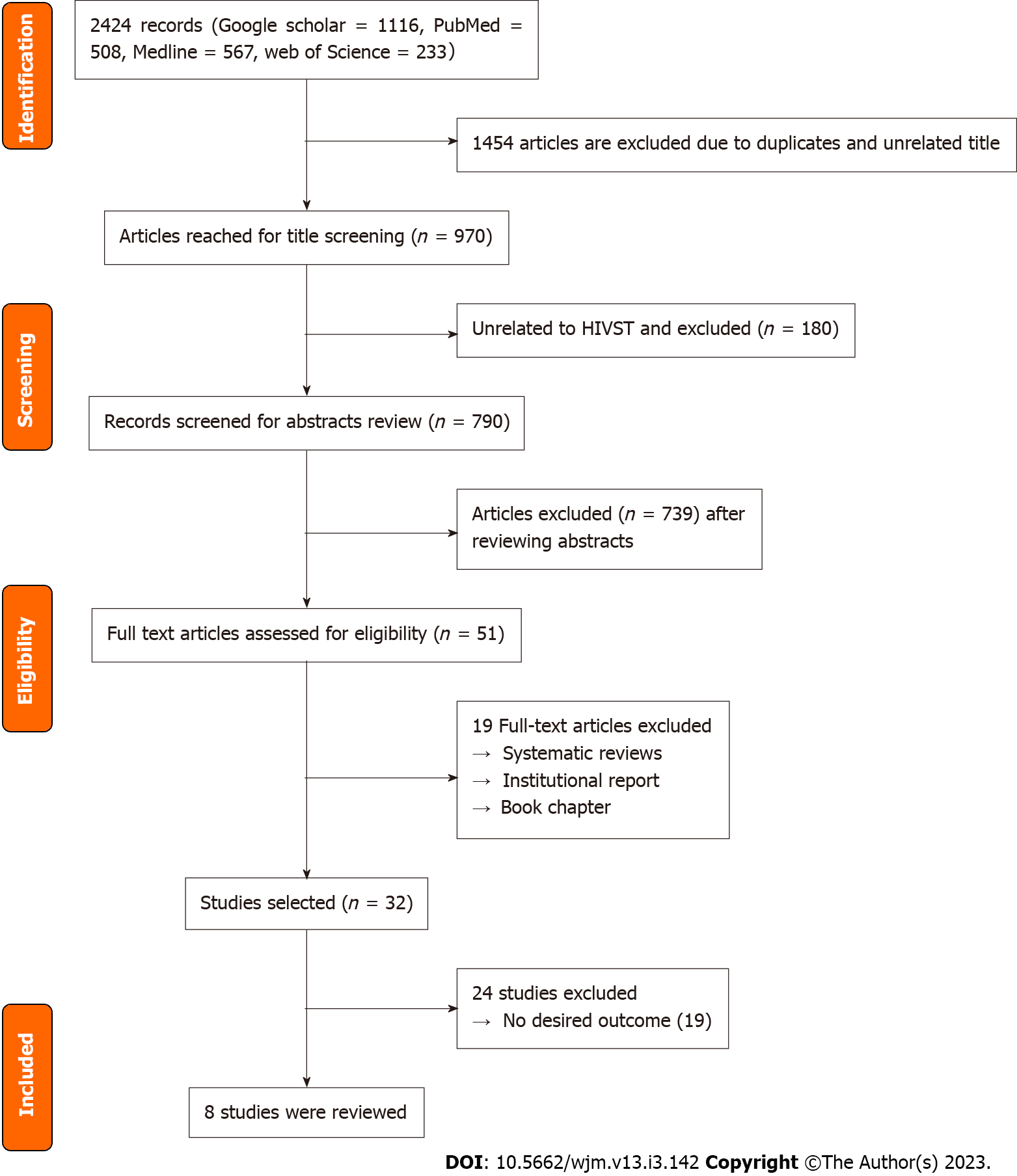

The scoping review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Figure 1). These reviews follow explicit, pre-specified and reproducible methods in order to identify, evaluate, and summarize the findings of all relevant individual studies (Grant and Booth, 2009)[12].

One of the authors (Adepoju VA) searched for eligible studies between October 15 and 20, 2022. The Arksey and O'Malley[13] (2005) methodological framework guided the scoping of the published data. The scoping review conducted in this study was not registered in a registry such as PROSPERO. We chose not to register this scoping review, as registration is not a mandatory requirement for scoping reviews and our primary aim is to provide a broad overview of the literature rather than conduct a systematic assessment of the evidence. Although the Reference Citation Analysis tool was available for use, it was not utilized for this review. This decision was made based on the nature of the research question and the inclusion and exclusion criteria developed for the review, which ensured that all relevant studies were identified through the comprehensive search strategy described above.

Searched databases included PubMed, MEDLINE, Web of Science, and Google Scholar. For studies that may have been missed in the electronic search, we used reference lists of all the articles identified for cross-referencing. The first search took place between October 1 and 6, 2022, whereas the second took place between October 8 and 14, 2022. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria were developed with caution, to make sure that they matched the review questions and involved sufficient details to help point out all relevant studies and exclude irrelevant ones. The researchers then embarked on a two-stage process in which two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts for eligibility to be included in the final selection of papers. A combination of terms was used in the database searches; specifically: “HIV self-testing,” OR “HIVST” OR “HIV self-screening” OR “HIVSS” AND “preferences” AND “values” AND “oral- and blood-based” OR “oral and fingerstick HIVST” OR Oral and capillary” OR “oral- vs blood-based.” Specific keywords were combined with Boolean operators in the literature search (Table 1).

| Search terms | OR | AND | AND |

| HIVST | HIV self-testing | HIV self-screening | |

| HIV self-testing | |||

| HIVSS | HIV self-screening | ||

| HIV self-screening | |||

| Blood-based HIVST | Fingerstick HIVST | Capillary HIVST | |

| Fingerstick HIVST | |||

| Capillary HIVST | Oral HIVST | ||

| Oral HIVST | |||

| Preference |

The systematic searches for eligible articles retrieved 2424 studies and 1454 duplicates were eventually removed. The authors (Adepoju VA, Imoyera W) independently screened the titles and abstracts for eligibility with the condition that if one or both authors identified the article as relevant, then the full-text review would be carried out. The researchers solved any disagreements via discussions and reached a consensus. After the title and abstract screening, two reviewers (Adepoju VA, Imoyera W) independently screened the full text of selected articles. Disagreements were resolved through discussions with a third reviewer (Onoja AJ) for final inclusion. The articles were selected in several parts, which allowed the reviewers to have a regular discussion of the eligibility criteria, ensuring the same understanding of the criteria, and the criteria remaining the same throughout the article selection phase. The researchers did not assess the risk of bias of the included studies. As in many scoping reviews, the goal was to describe preferences for oral- vs blood-based HIVST.

Studies published in peer-reviewed journals between January 2011 and October 2022 and focusing on preferences of oral- vs blood-based HIVST among actual users were reviewed.

Inclusion criteria were: primary studies with participants aged 15 years or more with no geographic or population limitations; studies reporting on user preferences for HIVST with only two comparison groups (i.e. oral- vs blood-based HIVST); studies that adapted HIV Point of Care for HIVST for research purpose only; and studies that included actual users of oral- and blood-based HIVST. Exclusion criteria were studies comparing either oral- or blood-based HIVST with facility-based test or any other HIV testing approaches (e.g., Voluntary Counselling and Testing, mail-in, Dry Blood Sample); studies evaluating user preferences for one type of HIVST only (i.e. oral- or blood-based specimen); studies where comparison group for preferences was not clear, not stated or measured qualitatively; and studies including hypothetical users rather than actual users of HIVST. Also excluded were articles published before January 2011, conference papers, books, studies with no full-text available, and magazines. This is because HIVST was not popular before this period and publications on this subject matter were either scarce or non-existent before this period. In accordance with PRISMA guideline 16b, we have cited and explained the exclusion of studies that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria but were ultimately excluded. The reasons for their exclusion are provided in the results and appendix section (Supplementary Table 1) ensuring transparency in the review process.

The authors extracted relevant data using a standard excel-based template. Two authors (Adepoju VA, Imoyera W) independently extracted the data, and the results were reviewed and verified by both authors for quality and clarity. Two authors (Adepoju VA, Onoja AJ) separately and independently assessed the full text of the potentially eligible publications. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. Initial agreement was obtained on 90% of the items, and discrepancies were discussed between authors until 100% agreement was obtained. The following information was extracted from the included studies: author name and year of study, study design, type of specimen, product type, population and age, prevalence of preference for oral- and blood-based HIVST and major findings (Table 2). After extracting relevant information from the studies, the authors constructed a more specific classification for preferences of oral- vs blood-based HIVST.

| Ref. | Country | Study design | Type of specimen | Product type | Population, age in yr | Preference for oral, % | Preference for blood, % | Other findings |

| Tonen-Wolyec et al[14], 2020 | The Republic of Congo | Cross-sectional | Oral vs Fingerstick | Oraquick, Exacto | General population,18-49 | 85.6 | 78.6 | Comparable accuracy. University education and higher risk increases BB preference |

| Trabwongwitaya et al[15], 2022 | Thailand | Cross-sectional | Oral vs Fingerstick | Oraquick, INSTI | Young adult KP,18-24 | 34.4 | 65.6 | Performance and interpretation, O-93.3%, 100%; B-89.5%,98% |

| Cassell et al[19] , 2022 | Cambodia | Cross-sectional | Oral vs Fingerstick | Oraquick, CombokitsAbbot | KPs, 15+ | 88.5 | 11.5 | Assisted-98.6%; Unassisted-1.4% |

| Shapiro et al[20], 2020 | South Africa | Cross-sectional | Oral vs Fingerstick | Oraquick, Atomo | Adult men, 18+ | 42 | 58 | 10% and 90% will prefer different and the same kit for repeat tests, respectively |

| Lippman et al[17], 20181 | South Africa | Cross-sectional | Oral vs Fingerstick BB | Oraquick, Atomo | MSM | 34.2 | 64.6 | 97% will use HIVST again if available in the future |

| Lee et al[16], 2022 | Australia | Randomized Clinical Trial (RCT) | Oral vs Fingerstick | Oraquick, Atomo | MSM,18+ | 41 | 58 | O-not swabbing both gum, placing buffer on stand; BB-filling test channel, squeezing finger for blood drop |

| Ritchwood et al[18], 2019 | South Africa | Qualitative | Oral vs Fingerstick | Not stated | Young adult,18-24 | 80 | 20 | Post-test opinion change on ease of use and trust in result |

| Gaydos et al[21], 2011 | United State | Crosssectional | Oral vs Fingerstick | Oraquick, Unigold | Emergency department, 18-64 | 91 | 9 | ‘Trust in result’ O-similar for initial HCW-led and client ST (91%); B-client BBST result more (91.7%) than HCW provided HIV test (77.8%) |

The search results are shown in Figure 1, along with a summary of the papers consulted (the PRISMA flow chart). Although 2424 research articles were retrieved initially from the databases, only 8 met the inclusion criteria for this scoping review.

During the study selection process, we identified several studies that initially appeared to meet our inclusion criteria but were ultimately excluded upon closer examination and based on the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. We have provided a comprehensive list of these excluded studies and the reasons for their exclusion in the Supplementary Table 1. By documenting this information, we aim to ensure transparency and reproducibility in our review and study selection process and to demonstrate compliance with PRISMA 16B.

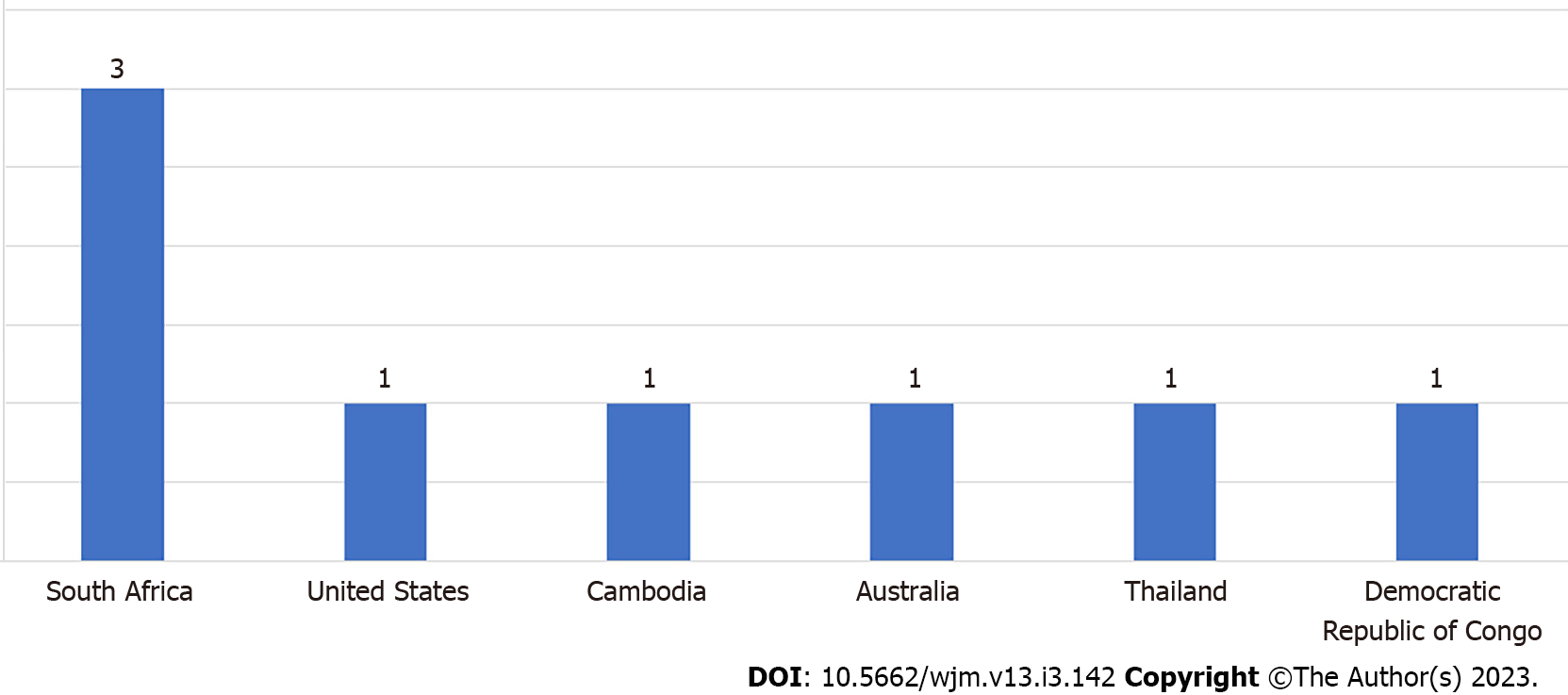

The total number of participants across the 8 studies was 7129 (40-4496). Of the eight studies reviewed, three studies were from South Africa and one each was from Cambodia, the United States, Thailand, Australia, and the Democratic Republic of Congo Figure 2. Three studies involved the general population (n = 3)[14-16], four involved the key population (n = 4)[14-17], and one involved young people (n = 1)[18]. A total eight studies, i.e. 6 quantitative studies[14,15,17,19-21], 1 randomized control trial[16], and 1 qualitative[18], were included in the study.

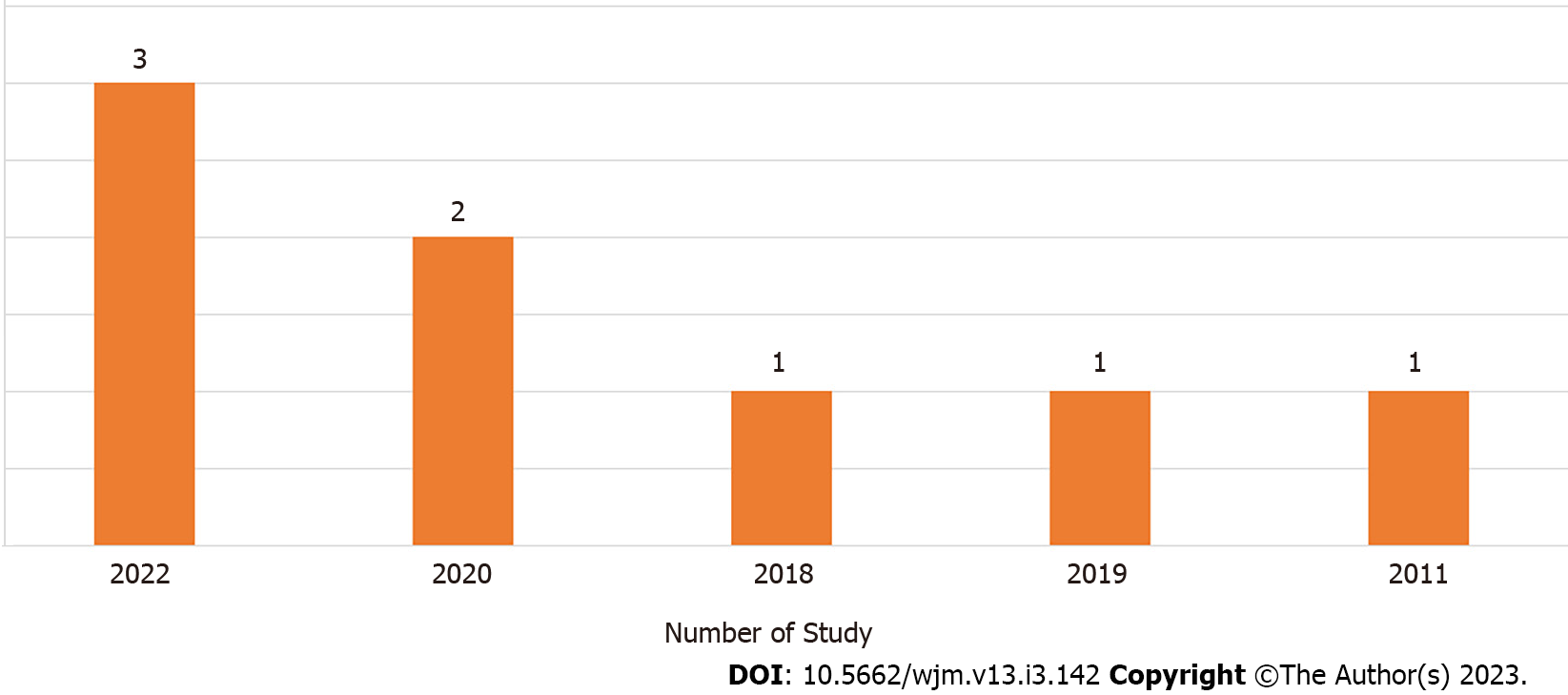

Out of the eight articles included, three were published in 2022[15,16,19], two in 2020[14,20], one in 2018[17], one in 2019[18], and one in 2011[21] (Figure 3).

One hundred percent of the studies reported preference based on the actual use of HIVST, and 50% reported usability. Four of the eight studies (50%) reported a higher preference for blood-based HIVST[16,18-20], whereas four of the eight studies (50%) reported a higher preference for oral HIVST[14,15,17,21]. Pooled preference for blood-based HIVST was 48.8% (9%-78.6%), whereas pooled preference for oral HIVST was 59.8% (34.2%-91%) across all studies. However, for male-specific studies[16,18-20], preference for blood-based HIVST (58%-65.6%) was higher than that for oral (34.2%-41%). The four studies that reported a higher preference for blood-based HIVST were in men, and participants considered blood-based HIVST to be more accurate and rapid whereas studies reporting higher preference for oral HIVST did so because they were considered non-invasive and easy to use with few false-negative results.

Overall, the study observed a slightly higher preference for oral than fingerstick HIVST. Similar to this finding, in studies among pregnant women in India[22], primary healthcare attendees in South Africa[23], female sex workers in China[24], and young people in Nigeria[25], participants who chose oral HIVST (over blood-based) cited ease of use and ability to avoid needle prick as reasons for choosing oral HIVST. Those who did not choose oral HIVST distrusted its capacity to detect HIV in saliva specimens. The distrust in HIV detection in saliva may have stemmed from HIV messaging that has historically emphasized that HIV can neither be acquired nor transmitted through kissing and oral sex[26,27]; hence, clients have questioned the scientific basis for HIV detection in oral fluid.

Furthermore, a significantly higher preference for blood-based HIVST than oral HIVST was noted in male-specific studies in this scoping review. Consistent with this finding, preferences for blood-based HIVST in men who have sex with men (MSM) in the United Kingdom and heterosexual men in Singapore were higher due to its accuracy, rapidity of results, and minimal false-negative results[28-30]. Preferences were also associated with certain factors such as previous testing, type of product used for recent testing, and presence of high-risk sexual behavior, indicating that these factors may influence individual preferences[31-33]. For instance, a study previously highlighted that individuals reporting recent high-risk sexual behaviors (e.g., unprotected sex, sex when drunk) were less likely to use oral HIVST[32], whereas the likelihood of using blood-based HIVST increased when offered with information on other sexually transmitted infections[33]. Men’s greater preference for blood-based HIVST was influenced by perceived higher risk, desire for accuracy, and perception of having lesser false-negative results[30]. Previous studies have also suggested that the accuracy of blood-based self-tests is higher than that of oral-fluid self-tests due to the lower quantity of HIV antibodies in oral fluid compared with whole blood[34] and reduced sensitivity for oral fluid testing for antibody detection (compared with blood testing) when specimen was obtained early after HIV infection[35]. Moreover, evaluation report of the third-generation blood-based HIVST showed very high sensitivity of 100% and high specificity of 99.9% and the ability of this product to detect HIV infections 7 d sooner than second-generation tests (i.e. from day 21 of infection instead of 28 d associated with most second-generation oral- and blood-based HIVST)[36]. One would expect usability of blood-based testing to be a major barrier, especially among men where preference was high. By contrast, a usability index average of 92.8% (92.2%-95.5% for oral HIVST; 84.2%-97.6% for blood-based HIVST) was reported in a study that evaluated the usability of seven WHO Prequalified HIVST kits (five blood-based and two oral HIVST) in South Africa[37]. Since both oral- and blood-based HIVST are complementary, a choice-based approach is therefore needed to optimize HIV testing programs and close the gaps between HIV testing and treatment.

There are several limitations to consider when interpreting our findings. First, we only used four databases to search the literature and may have missed articles not embedded. That notwithstanding, these databases are the basic sources of public health literature. Also, by not including conference abstracts, more recent unpublished articles may have been missed. Moreover, by reviewing citations of scoping and systematic reviews, the chances of incorporating the full breadth of the research through our search strategies were increased. We are convinced of having reached saturation with our methods. The real strength of the study lies in the inclusion of studies that offered both oral- and blood-based HIVST to actual users in real-world situations rather than experimental studies. This has removed the generalizability bias often seen in studies that offer only one type of HIVST or measure preferences from an intention-to-use perspective[38,39].

The scoping review consistently showed that men preferred blood-based HIVST than oral HIVST due to a higher risk perception and desire for a test that provides higher accuracy coupled with autonomy, rapidity, privacy, and confidentiality. The UNAIDS 2021 report showed a huge gap in knowledge of HIV status among general men and MSM, whereas AIDS-related death was higher in men than women due to late diagnosis, hence providing a blood-based HIVST option that can facilitate acceptability and the earlier diagnosis of HIV in men.

Similarly, the scoping review highlighted the diversity in preferences for oral- and blood-based HIVST and found that a single type of self-test kit is unlikely to cater for the preferences of diverse population and achieve high testing coverage. Integrating novel biomedical instruments into standard clinical and community procedures can occasionally prove difficult, as evidenced by the adoption of oral and injectable preexposure prophylaxis along with contemporary contraceptive methods. That notwithstanding, Ministries of Health and country programs should consider both blood and oral HIVST options. Offering choices among multiple kits may be the best way to maximize uptake and reach populations who may not otherwise test for HIV. Offering broader choices for HIVST could have a greater impact on testing uptake, but more research is needed to address misconceptions that drive HIVST and identify effective, population-specific dissemination channels needed to promote HIVST choices so people can make appropriately informed choices.

Human immunodeficiency virus self-testing (HIVST) has been shown to increase testing rates and improve early HIV diagnosis. However, there are different testing modalities, including oral- and blood-based HIVST, and little is known about the preferences for these different types of HIVST.

Identifying preferences for oral- vs blood-based HIVST is crucial for the development and implementation of effective HIVST programs. Understanding the factors that influence these preferences can also inform strategies for increasing uptake of HIVST.

The main objective of this scoping review was to provide a comprehensive overview of the literature on preferences for oral- vs blood-based HIVST. Specific objectives included identifying factors that influence preferences, exploring the implications of these preferences for the promotion and implementation of HIVST programs, and highlighting gaps in the literature.

A scoping review methodology was used to identify and synthesize relevant literature on preferences for oral- vs blood-based HIVST. The review included studies published in English between 2011 and 2021 that focused on actual and not hypothetical users of HIVST.

The search yielded 2424 records, of which 8 studies were included in the review. Across all studies, pooled preference for oral HIVST was 59.8%, whereas for blood-based HIVST, it was 48.8%. However, in studies specific to men, the preference for blood-based HIVST (58%-65.6%) was higher than oral (34.2%-41%). Men favored blood-based HIVST because of its perceived accuracy and rapidity, whereas oral HIVST was preferred for being non-invasive and easy to use.

Preferences for oral- vs blood-based HIVST are influenced by various factors, including user characteristics such as sex, testing context, and perceived test accuracy. Programs promoting HIVST should consider these factors when designing and implementing HIVST programs. Further research is needed to explore the impact of these preferences on HIV testing rates and to identify effective strategies for increasing the uptake of HIVST.

Future research should focus on identifying effective strategies for increasing the uptake of HIVST, particularly among populations that may have unique preferences or barriers to testing. Longitudinal studies could also help to explore the impact of these preferences on HIV testing rates and linkage to care. Additionally, studies should continue to explore the accuracy and feasibility of new HIVST technologies.

We would like to acknowledge all of the authors who shared the full text of their manuscripts with us.

| 1. | UNAIDS Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Confronting Inequalities: Lessons for Pandemic Responses From 40 Years of AIDS. UNAIDS Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2021. |

| 2. | UNAIDS. Missing men living with HIV. Jan 24, 2022. [cited 3 May 2023]. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/featurestories/2022/january/20220124_missing-men-living-with-hiv. |

| 3. | World Health Organization. Guidelines on HIV self-testing and partner notification: supplement to consolidated guidelines on HIV testing services. Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2016. [cited 3 May 2023]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/251655. |

| 4. | Wise JM, Ott C, Azuero A, Lanzi RG, Davies S, Gardner A, Vance DE, Kempf MC. Barriers to HIV Testing: Patient and Provider Perspectives in the Deep South. AIDS Behav. 2019;23:1062-1072. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bott S, Neuman M, Helleringer S, Desclaux A, Asmar KE, Obermeyer CM; MATCH (Multi-country African Testing and Counselling for HIV) Study Group. Rewards and challenges of providing HIV testing and counselling services: health worker perspectives from Burkina Faso, Kenya and Uganda. Health Policy Plan. 2015;30:964-975. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | The Global Fund. List of HIV Diagnostic test kits equipments classified according to the Global Fund Quality Assurance Policy. 2022. [cited 20 November 2022]. Available from: https://www.theglobalfund.org/media/5878/psm_productshiv-who_list_en.pdf. |

| 7. |

World Health Organization.

WHO List of Prequalified |

| 8. | Njau B, Covin C, Lisasi E, Damian D, Mushi D, Boulle A, Mathews C. A systematic review of qualitative evidence on factors enabling and deterring uptake of HIV self-testing in Africa. BMC Public Health. 19:1289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mantell JE, Khalifa A, Christian SN, Romo ML, Mwai E, George G, Strauss M, Govender K, Kelvin EA. Preferences, beliefs, and attitudes about oral fluid and blood-based HIV self-testing among truck drivers in Kenya choosing not to test for HIV. Front Public Health. 2022;10:911932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Strauss M, George G, Lansdell E, Mantell JE, Govender K, Romo M, Odhiambo J, Mwai E, Nyaga EN, Kelvin EA. HIV testing preferences among long distance truck drivers in Kenya: a discrete choice experiment. AIDS Care. 2018;30:72-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Indravudh PP, Sibanda EL, d'Elbée M, Kumwenda MK, Ringwald B, Maringwa G, Simwinga M, Nyirenda LJ, Johnson CC, Hatzold K, Terris-Prestholt F, Taegtmeyer M. 'I will choose when to test, where I want to test': investigating young people's preferences for HIV self-testing in Malawi and Zimbabwe. AIDS. 2017;31 Suppl 3:S203-S212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009;26:91-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3665] [Cited by in RCA: 3717] [Article Influence: 218.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005;8 pp:19-32. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Tonen-Wolyec S, Sarassoro A, Muwonga Masidi J, Twite Banza E, Nsiku Dikumbwa G, Maseke Matondo DM, Kilundu A, Kamanga Lukusa L, Batina-Agasa S, Bélec L. Field evaluation of capillary blood and oral-fluid HIV self-tests in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0239607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Trabwongwitaya P, Songtaweesin WN, Paiboon N, Wongharn P, Moonwong J, Phiphatkhunarnon P, Sowaprux T, Sophonphan J, Hansasuta P, Puthanakit T. Preference and ability to perform blood-versus oral-fluid-based HIV self-testing in adolescents and young adults in Bangkok. Int J STD AIDS. 2022;33:492-498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lee DY, Ong JJ, Smith K, Jamil MS, McIver R, Wigan R, Maddaford K, McNulty A, Kaldor JM, Fairley CK, Bavinton B, Chen M, Chow EP, Grulich AE, Holt M, Conway DP, Stoove M, Wand H, Guy RJ. The acceptability and usability of two HIV self-test kits among men who have sex with men: a randomised crossover trial. Med J Aust. 2022;217:149-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lippman SA, Lane T, Rabede O, Gilmore H, Chen YH, Mlotshwa N, Maleke K, Marr A, McIntyre JA. High Acceptability and Increased HIV-Testing Frequency After Introduction of HIV Self-Testing and Network Distribution Among South African MSM. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;77:279-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 92] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Ritchwood TD, Selin A, Pettifor A, Lippman SA, Gilmore H, Kimaru L, Hove J, Wagner R, Twine R, Kahn K. HIV self-testing: South African young adults' recommendations for ease of use, test kit contents, accessibility, and supportive resources. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cassell MM, Girault P, Nith S, Rang C, Sokhan S, Tuot S, Kem V, Dork P, Chheav A, Sos M, Im C, Meach S, Mao K, Ly PS, Khol V, Samreth S, Ngauv B, Ouk V, Seng S, Wignall FS. A Cross-Sectional Assessment of HIV Self-Testing Preferences and Uptake Among Key Populations in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2022;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Shapiro AE, van Heerden A, Krows M, Sausi K, Sithole N, Schaafsma TT, Koole O, van Rooyen H, Celum CL, Barnabas RV. An implementation study of oral and blood-based HIV self-testing and linkage to care among men in rural and peri-urban KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020;23 Suppl 2:e25514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Gaydos CA, Hsieh YH, Harvey L, Burah A, Won H, Jett-Goheen M, Barnes M, Agreda P, Arora N, Rothman RE. Will patients "opt in" to perform their own rapid HIV test in the emergency department? Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:S74-S78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sarkar A, Mburu G, Shivkumar PV, Sharma P, Campbell F, Behera J, Dargan R, Mishra SK, Mehra S. Feasibility of supervised self-testing using an oral fluid-based HIV rapid testing method: a cross-sectional, mixed method study among pregnant women in rural India. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19:20993. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kelvin EA, Cheruvillil S, Christian S, Mantell JE, Milford C, Rambally-Greener L, Mosery N, Greener R, Smit JA. Choice in HIV testing: the acceptability and anticipated use of a self-administered at-home oral HIV test among South Africans. Afr J AIDS Res. 2016;15:99-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Marley G, Kang D, Wilson EC, Huang T, Qian Y, Li X, Tao X, Wang G, Xun H, Ma W. Introducing rapid oral-fluid HIV testing among high risk populations in Shandong, China: feasibility and challenges. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Obiezu-Umeh C, Gbajabiamila T, Ezechi O, Nwaozuru U, Ong JJ, Idigbe I, Oladele D, Musa AZ, Uzoaru F, Airhihenbuwa C, Tucker JD, Iwelunmor J. Young people's preferences for HIV self-testing services in Nigeria: a qualitative analysis. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Alcorn K, Oral Sex the Risk of HIV Transmission. NAM AIDS Map. 2019. [cited 31 March 2022]. Available from: https://www.aidsmap.com/about-hiv/oral-sex-and-risk-hiv-transmission. |

| 27. | Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Ways HIV Can Be Transmitted. [cited 31 March 2022]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/hiv-transmission/ways-people-get-hiv.html#:~:text=Deep%2C%20Open%2DMouth%20Kissing, t%20transmit%20HIV%20through%20saliva. |

| 28. | Tan YR, Kaur N, Ye AJ, Zhang Y, Lim JXZ, Tan RKJ, Ho LP, Chen MI, Wong ML, Wong CS, Yap P. Perceptions of an HIV self-testing intervention and its potential role in addressing the barriers to HIV testing among at-risk heterosexual men: a qualitative analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2021;97:514-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Witzel TC, Rodger AJ, Burns FM, Rhodes T, Weatherburn P. HIV Self-Testing among Men Who Have Sex with Men (MSM) in the UK: A Qualitative Study of Barriers and Facilitators, Intervention Preferences and Perceived Impacts. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0162713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Frye V, Wilton L, Hirshfield S, Chiasson MA, Lucy D, Usher D, McCrossin J, Greene E, Koblin B; All About Me Study Team. Preferences for HIV test characteristics among young, Black Men Who Have Sex With Men (MSM) and transgender women: Implications for consistent HIV testing. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0192936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ostermann J, Njau B, Brown DS, Mühlbacher A, Thielman N. Heterogeneous HIV testing preferences in an urban setting in Tanzania: results from a discrete choice experiment. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Olakunde BO, Alemu D, Conserve DF, Mathai M, Mak'anyengo MO; NAHEDO Study Group, Jennings Mayo-Wilson L. Awareness of and willingness to use oral HIV self-test kits among Kenyan young adults living in informal urban settlements: a cross-sectional survey. AIDS Care. 2022;1-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Balán I, Frasca T, Ibitoye M, Dolezal C, Carballo-Diéguez A. Fingerprick Versus Oral Swab: Acceptability of Blood-Based Testing Increases If Other STIs Can Be Detected. AIDS Behav. 2017;21:501-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Figueroa C, Johnson C, Ford N, Sands A, Dalal S, Meurant R, Prat I, Hatzold K, Urassa W, Baggaley R. Reliability of HIV rapid diagnostic tests for self-testing compared with testing by health-care workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet HIV. 2018;5:e277-e290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Luo W, Masciotra S, Delaney KP, Charurat M, Croxton T, Constantine N, Blattner W, Wesolowski L, Owen SM. Comparison of HIV oral fluid and plasma antibody results during early infection in a longitudinal Nigerian cohort. J Clin Virol. 2013;58 Suppl 1:e113-e118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Abbott. CheckNOWTM HIV self test. [cited 10 May 2023]. Available from: https://www.globalpointofcare.abbott/en/product-details/checknow-hiv-self-test.html. |

| 37. | Majam M, Mazzola L, Rhagnath N, Lalla-Edward ST, Mahomed R, Venter WDF, Fischer AE. Usability assessment of seven HIV self-test devices conducted with lay-users in Johannesburg, South Africa. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0227198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Kelvin EA, Akasreku B. The Evidence for HIV Self-Testing to Increase HIV Testing Rates and the Implementation Challenges that Remain. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2020;17:281-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Merchant RC, Clark MA, Liu T, Romanoff J, Rosenberger JG, Bauermeister J, Mayer KH. Comparison of Home-Based Oral Fluid Rapid HIV Self-Testing Versus Mail-in Blood Sample Collection or Medical/Community HIV Testing By Young Adult Black, Hispanic, and White MSM: Results from a Randomized Trial. AIDS Behav. 2018;22:337-346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medical laboratory technology

Country/Territory of origin: Nigeria

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Kocazeybek B, Turkey S-Editor: Li L L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Li L