Published online Jun 20, 2023. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v13.i3.127

Peer-review started: January 5, 2023

First decision: March 15, 2023

Revised: April 1, 2023

Accepted: April 27, 2023

Article in press: April 27, 2023

Published online: June 20, 2023

Processing time: 166 Days and 0.6 Hours

In 2019, the Nigerian Ministry of Health published the first operational guidelines for human immunodeficiency virus self-testing (HIVST) to improve access to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing services among undertested populations in the country. Also, as part of the campaign to increase HIV testing services in Nigeria, the Nigerian Ministry of Health developed standard operating procedures for using HIVST kits.

To systematically review the acceptability and strategies for enhancing the uptake of HIVST in Nigeria.

The systematic review was conducted and reported in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. Different databases were searched to get the necessary materials needed for this review. Standardized forms developed by the authors were used for data extraction to minimize the risk of bias and ensure that the articles used for the study were properly screened. Identified articles were first screened using the titles and their abstracts. The full papers were screened, and the similarities of the documents were determined. Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-method studies were evaluated using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme and Critical Appraisal Framework criteria.

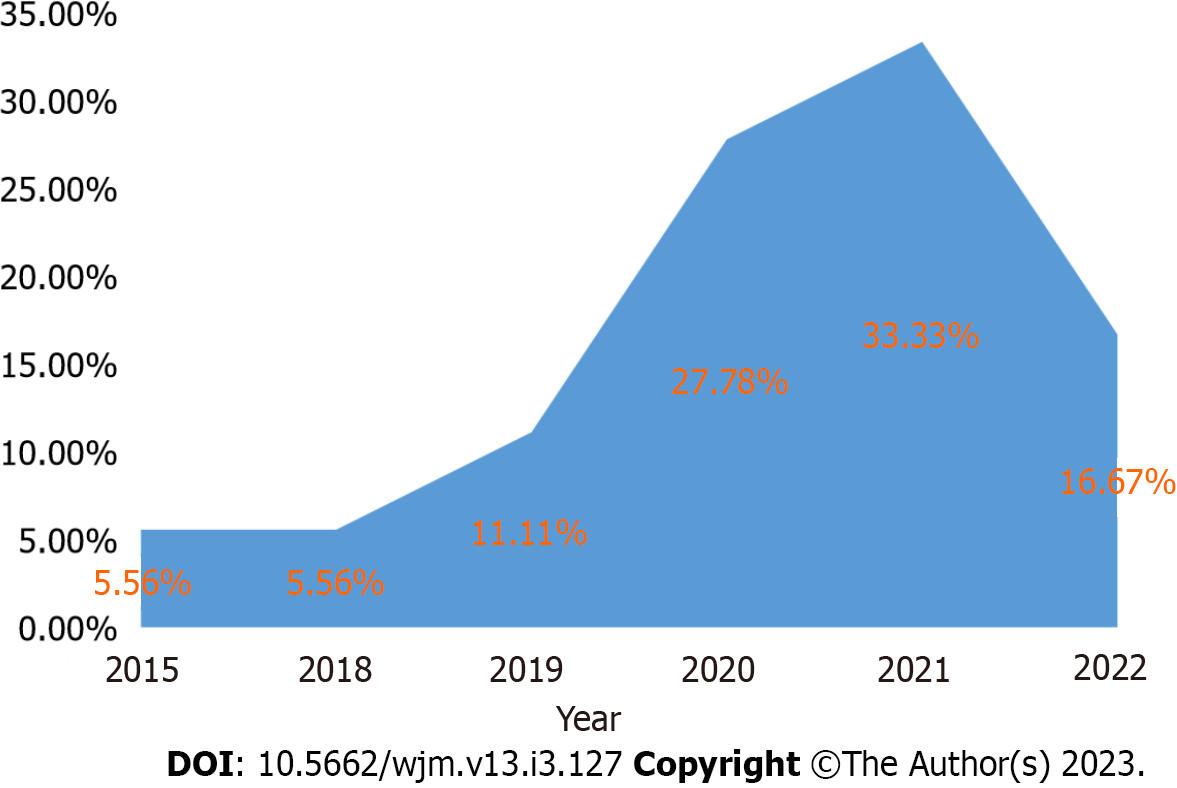

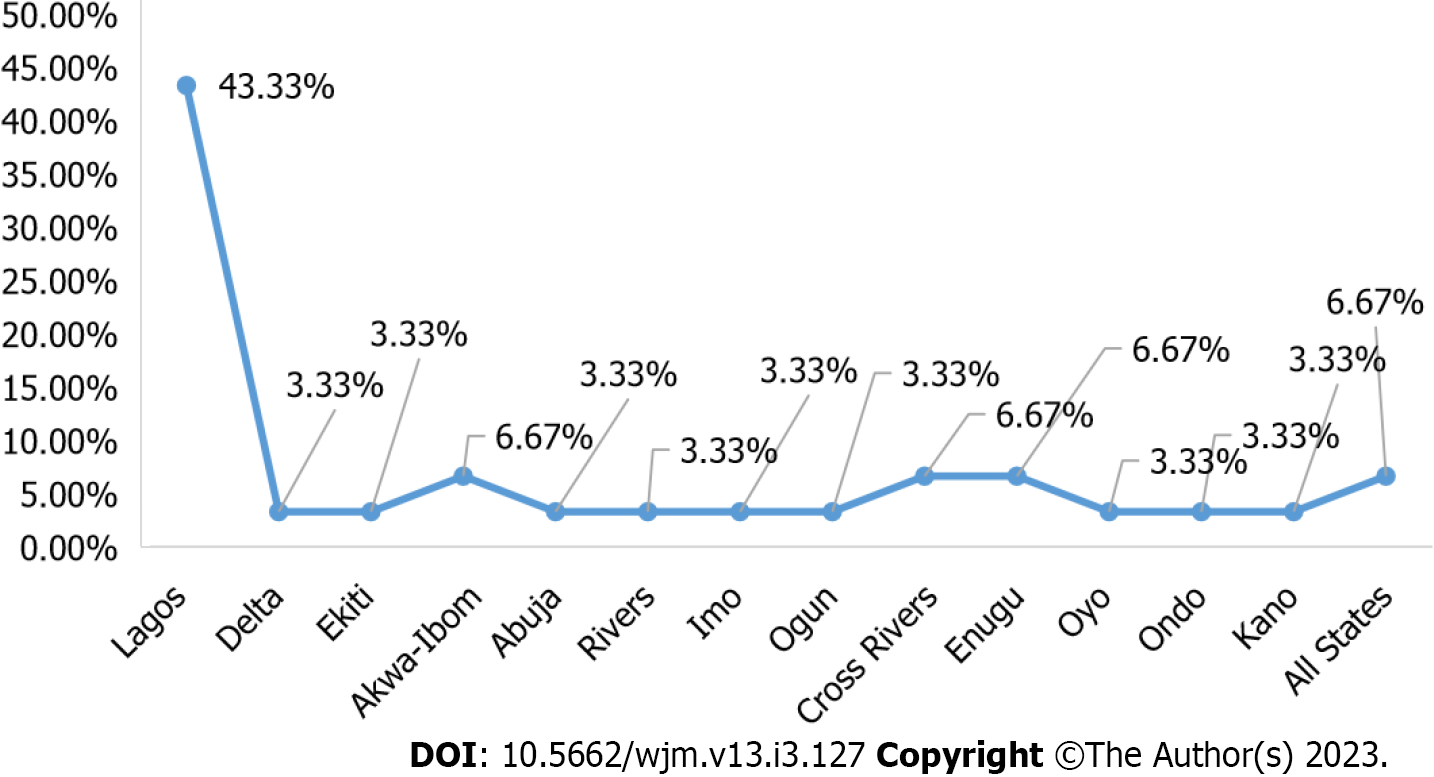

All the publications reviewed were published between 2015 and 2022, with 33.3% published in 2021. Most (77.8%) of the studies were cross-sectional, 43.3% were conducted in Lagos State, and 26.3% were conducted among young people. The study revealed a high level of acceptability of HIVST. Certain factors, such as gender, sexual activity, and previous testing experience, influence the acceptability of HIV self-testing, with some individuals more likely to opt-out. The cost of the kit was reported as the strongest factor for choosing HIVST services, and this ranged from 200 to 4000 Naira (approximately United States Dollar 0.55-11.07), with the majority willing to pay 500 Naira (approximately United States Dollar 1.38). Privately-owned, registered pharmacies, youth-friendly centres, supermarkets, and online stores were the most cited access locations for HIVST. The least influential attribute was the type of specimen needed for HIVST. Strategies addressing cost and preferred access points and diverse needs for social media promotion, local translation of product use instructions, and HIVST distribution led by key opinion leaders for key populations were found to significantly enhance HIVST uptake and linkage to care.

HIVST acceptability is generally high from an intention-to-use perspective. Targeted strategies are required to improve the acceptability of HIV self-testing, especially among males, sexually active individuals, and first-time testers. Identified and proposed uptake-enhancing strategies need to be investigated in controlled settings and among different populations and distribution models in Nigeria.

Core Tip: This is the first systematic literature review on the acceptability and uptake of human immunodeficiency virus self-testing (HIVST) in Nigeria. The findings suggested that the acceptability of HIVST is high in Nigeria. However, the actual use of HIVST in programmatic implementation was lower than expected. The use of key opinion leaders among key populations successfully increased the acceptability and uptake of HIVST. However, cost was a major barrier to the acceptability of HIVST. More studies are required to evaluate how the uptake of HIVST compares in routine programs vs real-life settings in the absence of support and resources that enhance HIVST uptake.

- Citation: Adepoju VA, Umebido C, Adelekan A, Onoja AJ. Acceptability and strategies for enhancing uptake of human immunodeficiency virus self-testing in Nigeria. World J Methodol 2023; 13(3): 127-141

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v13/i3/127.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v13.i3.127

Nigeria is ranked second among the countries with a high burden of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in the world[1]. In 2018, the national prevalence of HIV was 1.5%, with an estimated 1.9 million people living with HIV/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), of which only 30.0% were on antiretroviral therapy[2]. According to the Nigeria HIV/AIDS Indicator and Impact Survey, the national HIV prevalence rate in the group of 15-49 years of age was 1.4%, with a population of 201 million in 2019[3]. In Nigeria, 53000 people died of HIV/AIDS in 2018, while the rate of HIV/AIDS-related deaths appears to have remained constant in recent years, owing to the ongoing problem of advanced HIV disease[4].

Despite increased scientific and medical advancement in the understanding and management of HIV, a large number of those infected remains untested and unaware of their serostatus[5]. One of the reasons for the poor coverage of conventional health facility-based counselling and testing is the refusal to test due to the fear of societal stigma and discrimination that may result from a positive HIV test result[6] and the fear of long-term treatment, which may affect the quality of life of those infected[7].

The World Health Organization recommends HIV self-testing (HIVST) as a tool for improving the uptake of HIV testing services and achieving the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS 90-90-90 target[8]. HIVST is an unconventional and innovative strategy to reach the first 90% goal of the United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS by facilitating access to testing for early detection and prevention of HIV transmission[9]. Evidence shows that the deployment of HIVST has improved the uptake of HIV testing among men[10-13] in several countries implementing HIVST in Sub-Saharan Africa including South Africa, Zimbabwe, and Botswana[10-12].

Nigeria has identified the need to increase HIV counselling and testing, including the potential of a self-testing methodology[14]. In 2019, the national AIDS and sexually transmitted diseases control programme under the Federal Ministry of Health developed the operational guidelines for the delivery of HIVST in Nigeria. The document provides guidance for the operationalization of HIVST in Nigeria including the different service delivery and distribution models, procurement and supply chain management, monitoring, and evaluation among others[5]. HIVST addresses the gap in HIV testing, especially in clinical settings. Surveys conducted among diverse populations in Malawi, Spain, the United States, and Nigeria showed varying interest in HIVST and acceptability ranges between 22% and 88%[15-19]. There is no study that systematically documented evidence either on the acceptability of HIVST or the proposed strategies to enhance its uptake in Nigeria. HIVST, as an innovative tool, is still a growing intervention in Nigeria with potential barriers to its acceptance among populations and settings. This study, therefore, aimed to systematically review the acceptability, existing regulations, and strategies for enhancing the uptake of HIVST in Nigeria.

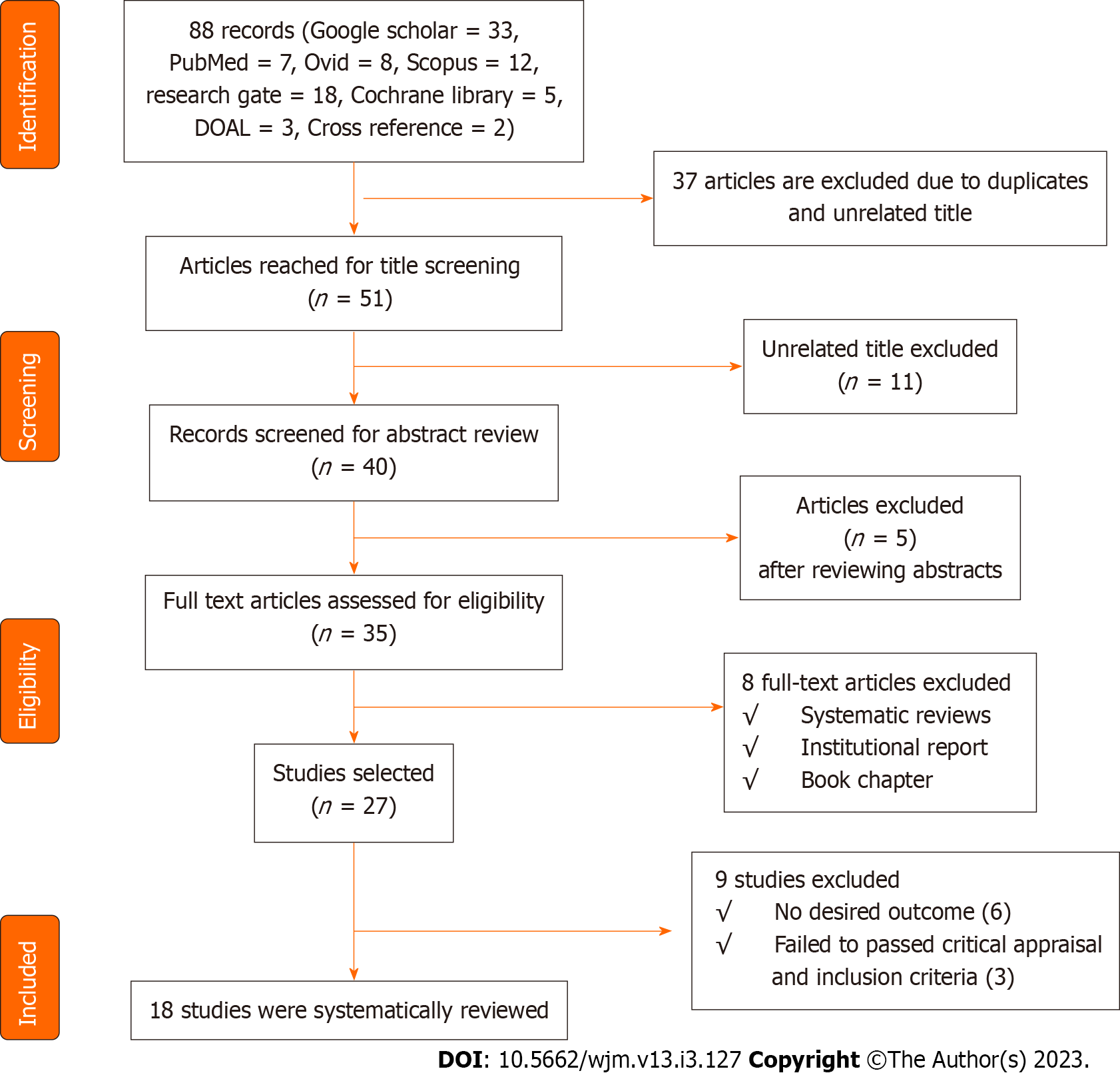

A systematic review was conducted and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (Figure 1).

Different databases were searched to get the necessary materials needed for this review. A scientific literature search was performed using Elsevier, Google Scholar, EMBASE, PubMed, Ovid, and Scopus databases. Grey literature was also searched from Google and Google literature, the largest databases for grey literature. Additionally, literature was systematically searched from ResearchGate, Cochrane library, and Directory of Open Access Journal. For studies that may have been missed in the electronic search, cross reference was undertaken using reference lists of all identified articles. The first search was conducted between April 4-8, 2022, while the second took place between April 15-20, 2022. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria were cautiously developed to match the review questions and have sufficient details to pinpoint all relevant studies and exclude irrelevant studies[20]. The literature search combined specific keywords with Boolean operators (Table 1). Although the Reference Citation Analysis tool was available for use, it was not utilized for this review. This decision was formed based on the nature of the research question and the inclusion and exclusion criteria developed for the review, which ensured that all relevant studies were identified through the comprehensive search strategy described above.

| Search terms | And | And |

| HIV self-testing | Acceptability | Nigeria |

| HIV regulatory | Nigeria | Self-testing |

| HIV self-testing | Preference | Nigeria |

| Nigeria HIV uptake | Self-testing Nigeria | |

| HIV self-testing | Nigeria treatment | Linkage |

Both qualitative and quantitative studies on HIVST in Nigeria were included in this study.

Articles were excluded if no data was found for the desired outcome. Editorials and short commentaries were also excluded. Papers that were not peer-reviewed and those that the full text could not be assessed were also excluded.

Standardized forms developed by the authors were used for data extraction to minimize the risk of bias. One of the authors extracted data from the included studies, while the other authors checked these datasets. Discrepancies were resolved by referring to the original studies. Data on acceptability, existing regulatory context, and preference level for HIVST in Nigeria were extracted. Other data extracted include the level of uptake, linkage to treatment, and strategies for enhancing the uptake of HIVST in Nigeria. Adelekan A and Adepoju VA independently evaluated the potential eligibility of each of the abstracts and titles from the retrieved citations after requesting full-text versions of these potentially eligible studies. Onoja AJ and Umebido C independently assessed the full text of the potentially eligible publications. Disagreements were resolved by consensus. Discrepancies were discussed between authors until a 100.0% agreement was achieved. The following information was extracted from the included studies: Authors, title, study population, study state, study objective(s), study design, and study findings.

The articles used for the review were properly screened. They were first screened using the titles and their abstracts. The full papers were screened, and the similarities of the papers were determined by reading the title, author(s), and abstract. The papers were then de-duplicated. The quality assessment of each study selected was based on set criteria[21,22].

The qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-method research were evaluated using the critical appraisal skills programme instrument[23] and critical appraisal framework criteria[24,25].

In compiling and summarizing the findings of the included studies, the researchers employed a variety of methodologies. Cleaning of data in the extraction sheet was an important step before analysis. The researchers structured the data from the extraction sheet into a format that analytical tools could read. The analysis was divided into qualitative and quantitative. Quantitative data analysis involved descriptive and narrative data. This technically followed the process of classification and tabulations. Content analysis technique was used for the qualitative data analysis.

The search results are shown in Figure 1, along with a synopsis of the papers consulted (the PRISMA flow chart). Although the databases contained 88 research articles, only 18 met the inclusion criteria for this systematic review (Table 2).

| Ref. | Title | Study population | State of study | Objectives/research question | Study design | Findings |

| Adebimpe et al[7], 2019 | How acceptable is the HIV/AIDS self-testing among women attending immunization clinics in Effurun, Southern Nigeria | All women of reproductive age (15-49 year) attending the immunization clinic (for their children) in Ekpan General Hospital | Delta | Assess the knowledge and acceptability of HIVST among women of childbearing age attending immunization clinics in Effurun, Southern Nigeria | Descriptive cross-sectional study | The study respondents’ high knowledge levels and acceptability of HIVST lend support to the fact that the procedure should be promoted in the stakeholders’ efforts to improve HIV testing among the general population |

| Adeoti et al[30], 2021 | Sexual practices, Risk perception, and HIV Self-Testing acceptability among long-distance truck drivers in Ekiti State, Nigeria | Adult male long-distance truck drivers in Ado-Ekiti, Southwestern Nigeria | Ekiti | Examined the sexual practices, risk perception, and HIVST acceptability among long-distance truck drivers in Ekiti State, Nigeria | Cross-sectional study | Many long-distance drivers were engaged in unsafe sexual practices and were at risk for HIV transmission. Increasing testing using HIVST has the potential to bridge the gap in the diagnosis of HIV among long-distance drivers who are willing to be tested |

| Brown et al[27], 2015 | HIVST in Nigeria: Public opinions and perspectives | Researchers, academics, journalists, community advocates, activists, and HIV policymakers and programmers, including those working in the development sectors, enlisted on the new HIV vaccine and microbicide advocacy society listserv | All states | Obtained perspectives of informed members of the Nigerian public on the use of the HIVST | Cross-sectional study | Cost-based pricing can be based on and directly tied to current product experiences and information as well as how crucial product monitoring is when pricing a product |

| Dirisu et al[28], 2020 | ‘I will welcome this one 101%, I will so embrace it’: A qualitative exploration of the feasibility and acceptability of HIV self-testing among MSM in Lagos, Nigeria | MSM | Lagos | Explored MSM perceptions of oral HIVST and potential barriers to and facilitators of HIVST use. In addition, it sought to identify operational and contextual issues that might affect the distribution of HIVST kits to MSM in the Nigerian context and the potential for linkage to care | Qualitative descriptive study | The potential of HIVST to increase the uptake of HIV testing among MSM in Nigeria was supportive of HIVST. Privacy and convenience offered by HIVST address concerns about stigma and waiting times associated with facility-based testing |

| Iliyasu et al[15], 2020 | Acceptability and correlates of HIV self-testing among university students in northern Nigeria | University students | Kano | Examine the acceptability of HIVST and identify factors associated with the uptake of HIVST services among university students in Kano, Nigeria | Cross-sectional study | HTS uptake was low among a sample of university students in northern Nigeria, but most university students were willing to self-test for HIV |

| Iwelunmor et al[36], 2020 | The 4 youth by youth HIV self-testing crowdsourcing contest: A qualitative evaluation | All young people between the ages of 10 year to 24 year in Nigeria | All states | Describe the responses to a crowdsourcing contest aimed at soliciting ideas on promoting HIVST among young people in Nigeria | Qualitative study | The study informed the development of innovative youth implementation strategies to increase the uptake of HIVST among adolescents and youth at risk for HIV |

| Agada et al[5], 2021 | Reaching out to the hard-to-reach populations with HIV self-testing services in South-south Nigeria | General population | Cross River and Akwa-Ibom | Assess the impact of the total market approach deployed in Cross River and Akwa Ibom States in South-south Nigeria to enhance the demand for HIVST to ensure product equity, accessibility, and sustainability | Retrospective cross-sectional study | The HIVST model demonstrated the potential to be a vital tool in expanding HIV testing services and linking HIV care services to populations who would otherwise not have been tested |

| Dirisu et al[34], 2020 | Exploring the regulatory context for HIV self-testing and PrEP market authorisation and use in Nigeria | PPMVs and CPs | Abuja, Rivers, Imo, Lagos, and Ogun | Assess HIVST/PrEP availability and market authorization; determine the facilitators and barriers to access; and identify existing systems that support the availability, appropriate use, affordability, and accessibility in the private sector in Nigeria | Cross-sectional study | About 63% of CPs and 27% of PPMVs sold HIVST kits, while 15% of CPs and no PPMV sold PrEP in their facilities. Most CPs (94%) and 33% of PPMVs who sold HIVST kits reported that their facilities were authorized to sell HIVST kits |

| Nwaozuru et al[26], 2019 | Preferences for HIV testing services among young people in Nigeria | Youth aged 14–24 year | Lagos | Assessed preferences for HIV testing options among young people in Nigeria | Cross-sectional study | HIV testing services was optimized to reach young people in various options to meet their unique preferences |

| Ong et al[33], 2021 | Designing HIV Testing and Self-Testing Services for young people in Nigeria: A discrete choice experiment | Nigerian youth (14-24 year) | Lagos | Examine the strength of Nigerian youth preferences related to HIV testing and HIVST | Discrete choice experiments | There could be demand for HIVST for Nigerian youth, who prefer HIVST kits that integrate testing for other STIs and is accessed from community health centres |

| Obiezu-Umeh et al[32], 2021 | Young people’s preferences for HIV self-testing services in Nigeria: A qualitative analysis | Young people (14–24 year) | Lagos | Use qualitative methods to examine HIVST preferences among Nigerian youth | Cross-sectional study | HIVST preferences among Nigerian youth appeared to be influenced by several factors, including lower cost, less invasive testing method, location of testing, and linkage to care and support post-testing. Findings underscored the need to address young people’s HIVST preferences as a foundation for implementing programs and research to increase the uptake of HIVST |

| Obiezu-Umeh et al[51], 2020 | Development of HIVST services through youth engagement: A qualitative evaluation of a health designation in Nigeria | Young people (14–24 year) | Lagos | Explore strategies for HIVST delivery developed at a designations contest in Nigeria | Cross-sectional study | Designations were a feasible method of facilitating meaningful youth engagement to develop deployable strategies to increase the uptake of HIV testing in young people in Nigeria |

| Durosinmi-Etti et al[38], 2021 | Communication needs for improved uptake of PrEP and HIVST services among key populations in Nigeria: A mixed-method study | MSM, FSWs, and key influencers of the KP groups (health providers, peer educators, HIV program officers) | Akwa Ibom, Cross River, and Lagos | Identify the communication needs and preferences of the KP groups as evidence for developing strategies and interventions to increase awareness and use of HIVST and PrEP services among the KPs in Nigeria | Cross-sectional study | KPs effectively networked to increase awareness and access to PrEP and HIVST services in Nigeria. They will make the peers receptive to the interventions and help them reach other peers in their network, especially the hard-to-reach |

| Sekoni et al[37], 2022 | Operationalizing the distribution of oral HIVST kits to MSM in a highly homophobic environment: the Nigerian experience | MSM and KOL | Lagos | Explore the operationalization of using KOLs to distribute HIVST kits to MSM | Cross-sectional study | This study showed the practical steps involved in operationalizing the KOL support system distribution of HIVST that positively influenced the testing experience for the participants irrespective of their HIV status and engagement in care. KOLs were a reliable resource to leverage for ensuring that HIVST kit was utilized, and HIV-positive individuals were linked to treatment and care in homophobic environments |

| Iwelunmor et al[52], 2022 | Enhancing HIVST among Nigerian youth: Feasibility and Preliminary Efficacy of the 4 youth by youth study using crowdsourced youth-led strategies | Youth (14-24 year) | Lagos, Enugu, Ondo, and Oyo | Examine the feasibility and efficacy of crowdsourced youth-led strategies to enhance HIVST and STI testing | Quasi-experimental | The study provided promising evidence of efficacy that youth-led, crowdsourced strategies led to higher uptake of HIV and STI testing |

| Tun et al[35], 2018 | Uptake of HIVST and linkage to treatment among MSM in Nigeria: A pilot programme using key opinion leaders to reach MSM | Males (17-59 year) | Lagos | Assess the feasibility, acceptability, uptake of HIVST, and linkage to HIV treatment among MSM through KOLs in Lagos, Nigeria | Cohort study | HIVST distribution through KOLs was feasible, and oral self-testing was highly acceptable among this urban MSM population. This study showed that linkage to treatment could be achieved with active follow-up and access to a trusted MSM-friendly community clinic that offers HIV treatment. HIVST should be considered an additional option to standard HIV testing models for MSM |

| Ugwu et al[29], 2020 | HIVST: Perspectives from primary healthcare workers in Enugu State, Southeast Nigeria | Health workers in the primary health facilities | Enugu | Assess issues surrounding the HIVST from the perspectives of the primary healthcare workers in Enugu State | Cross-sectional study | Most of the primary healthcare workers in Enugu State had poor knowledge of HIVST |

| Iliyasu et al[31], 2022 | HIVST and repeat testing in pregnancy and postpartum in Northern Nigeria | Pregnant women | Kano | Determine the predictors of willingness to self-test for HIV when retesting in pregnancy and postpartum among antenatal clients at a large teaching hospital in Northern Nigeria | Cross-sectional | The acceptability of HIVST for repeat testing in pregnancy and postpartum was low, but most respondents desired to be trained to self-test for HIV |

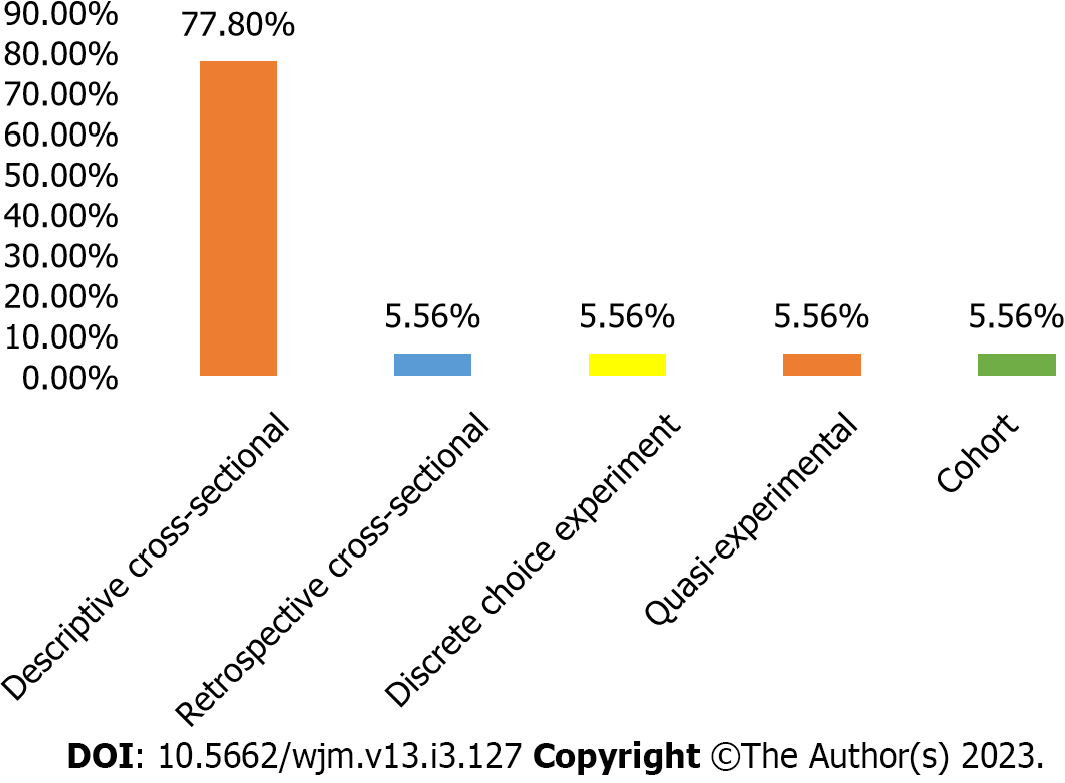

The included studies were published between 2015 and 2022, with 33.3% published in 2021 (Figure 2). Majority (77.8%) of the studies were cross-sectional in design (Figure 3), 43.3% were carried out in Lagos State (Figure 4), and 26.3% were conducted among young people (Table 3).

| Population | n | Frequency, % |

| Young people aged 15-24 yr | 5 | 26.3 |

| MSM | 3 | 15.8 |

| Key population influencers | 2 | 10.5 |

| Women of reproductive age | 1 | 5.3 |

| Long distance drivers | 1 | 5.3 |

| Professionals1 | 1 | 5.3 |

| Student at university | 1 | 5.3 |

| General population | 1 | 5.3 |

| PPMV and CP | 1 | 5.3 |

| FSW | 1 | 5.3 |

| Males aged 17-59 yr | 1 | 5.3 |

| Pregnant women | 1 | 5.3 |

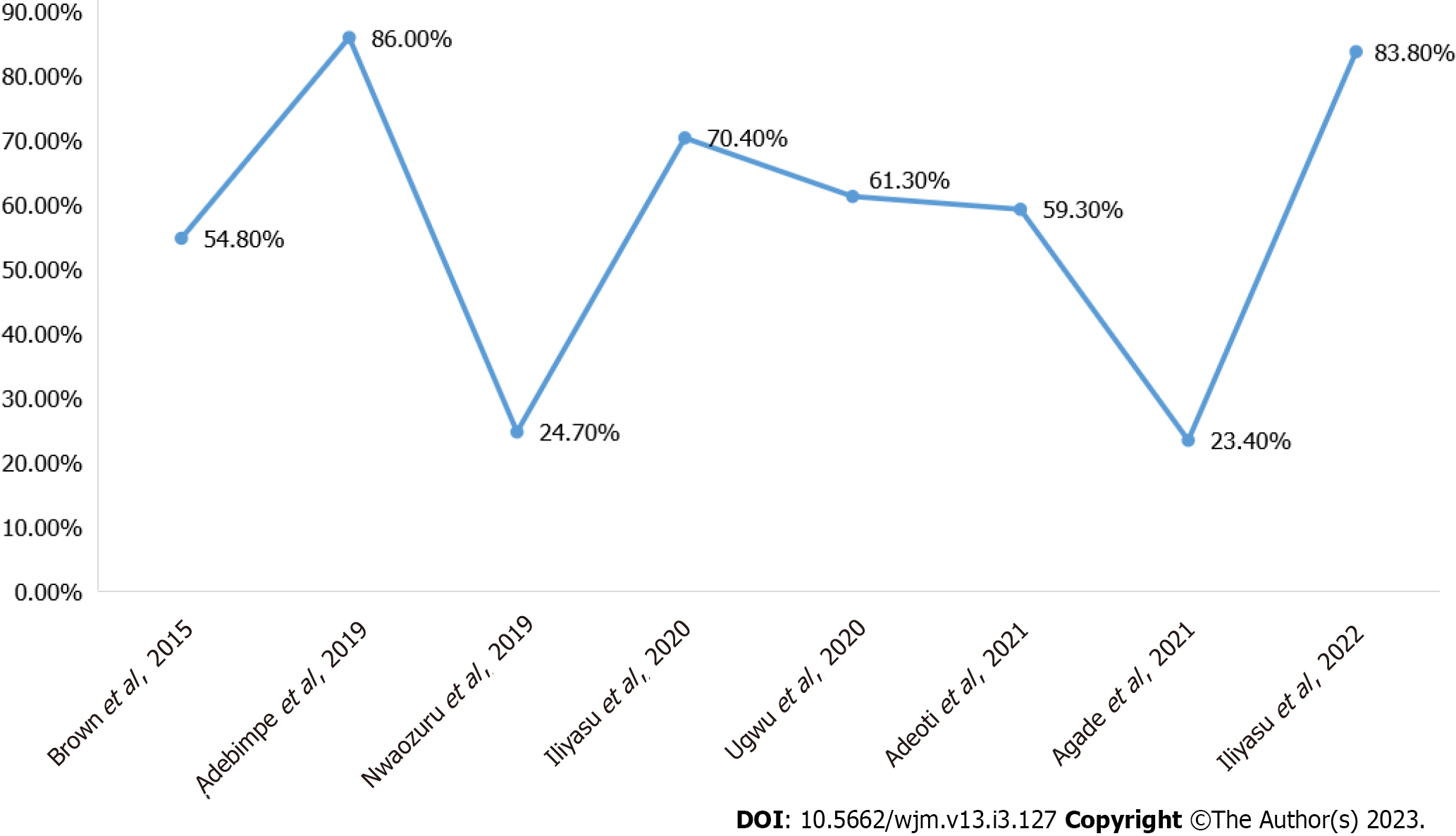

This review operationally defined the acceptability of HIVST as an intention to use, willingness to use, actual collection, and interest in use. The findings of most studies from Nigeria[5,7,26-31] revealed a high level of acceptability of HIVST compared to what was reported by a study from Northern Nigeria[15] (Figure 5). Brown et al[27] reported that 54.8% of the respondents supported having HIVST in Nigeria. Adebimpe et al[7] also reported that 86.0% of the respondents agreed that they would accept HIVST if kits were available, and 84.0% agreed that they would be willing to introduce and recommend HIVST to others. In another qualitative study by Dirisu et al[28] it was observed that most participants were willing to use oral HIVST kits.

Iliyasu et al[15] found that 70.4% of university students in northern Nigeria were willing to self-test for HIV and pay for the test kits. Specifically, 55.9% of the participants were willing to pay for the test kits themselves, and 14.5% were willing to pay for the test kits if they were cheaper. Additionally, 61.4% of the participants were willing to self-test with a sexual partner[15]. Also, Ugwu et al[29] reported that 61.3% of the health workers working in primary health care centres preferred HIVST over the facility-based testing modalities. In 2021, a study also reported that 59.3% of the respondents were interested in HIVST[30]. In another study, it was observed that nearly all (99.5%) of the pregnant women enrolled in the study preferred conventional HIV testing service at booking. However, 83.8% of these pregnant women were keen to learn how to self-test for HIV, and 85.7% of the respondents were willing to repeat the HIV test during pregnancy, of which 29.3% were willing to self-test[31]. Similarly, 94.6% of respondents were willing to retest for HIV after delivery, of which 27.4% were willing to self-test.

However, another study among young people in Nigeria noted that more than half (69.9%) of the participants indicated they would prefer a physician to administer the HIV test. In comparison, the proportions of those who preferred HIV tests administered by a nurse and self-administered HIV tests were 15.7% and 4.8%, respectively. Another study from Southern Nigeria reported that 23.4% of the respondents accepted HIVST, of which 33.3% of the clients were assisted[5]. In terms of preference of oral vs blood-based HIVST in Nigeria, another study by Obiezu-Umeh et al[32] reported that oral-based HIVST was preferred by most of the young participants when compared to blood-based HIVST.

Ong et al[33] used a discrete choice experiment to design HIVST services for young people in Nigeria. The authors reported that male individuals (compared with female individuals), those who never had sex (compared with sexually active), and those who had never tested for HIV before (compared with those who had previously tested) were more likely to opt-out of using an HIVST kit.

Only one study examined the regulatory context for HIVST in Nigeria. The study by Dirisu et al[34] examined the regulatory framework for HIVST in Nigeria, revealing several issues. Of the providers who marketed HIVST kits, 94.0% of community pharmacists (CPs) and 33.0% of patent proprietary medicine vendors (PPMVs) claimed to be authorized to sell them[34]. Despite the existence of a National Drug Policy and an automated product registration system administered by the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control, the process for authorizing, manufacturing, and distributing medical products was reported as cumbersome, time-consuming, and costly[34]. Furthermore, the National Drug Distribution Guideline was not implemented, leading to an uncoordinated supply chain. The study also found that less than half (45.6%) of PPMVs and CPs had a standard operating manual for administering HIVST, and about one-third had standard guidelines for HIV testing services. While 77.0% of providers offered counselling before selling HIVST, only 23.0% of CPs and 13% of PPMVs that sold HIVST were accredited HIV counselling and testing centres[34]. These findings demonstrate the need for improved regulatory oversight and support for HIVST imple

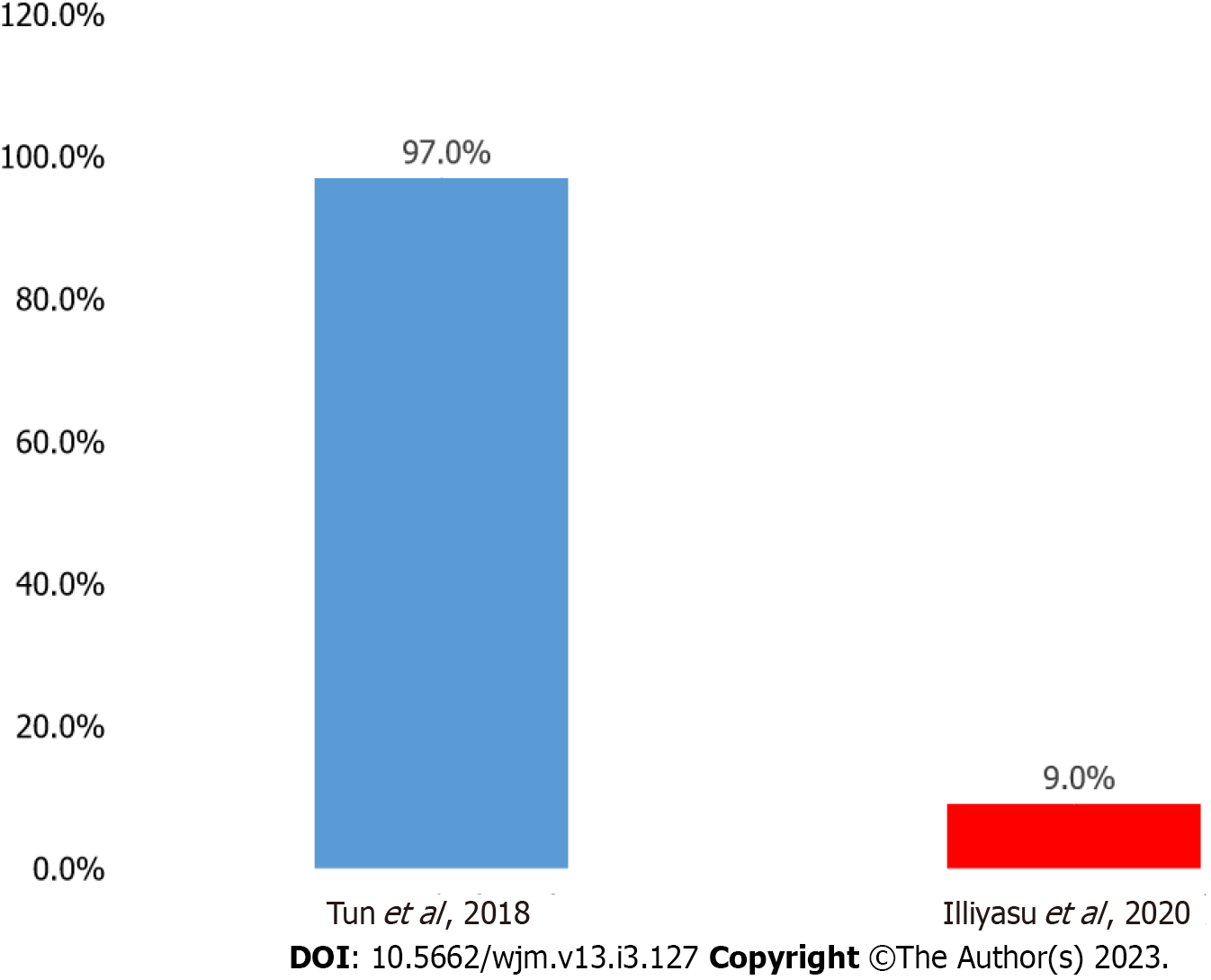

A cohort study on the uptake of HIVST revealed that 97.0% had used self-testing kits. Among these, almost a quarter (22.7%) tested themselves the same day they received the kit, and 49.4% tested within 1 week. About one-quarter (23.5%) reported that they had someone else present while they tested. Of these, 55.0% tested with a friend, 21.7% tested with a family member, 16.7% tested with a sex partner, and 6.7% tested with a key opinion leader (KOL)[35]. Another study revealed that 9.0% of the respondents reported previous HIVST[15] (Figure 6).

Regarding linkage to care after HIVST, it was reported that in Cross River State 14 of the 15 clients who reported reactive results (93.3%) were linked to confirmatory testing. Of the 14 linked to confirmatory testing, 13 (91.0%) were confirmed positive, and all (100.0%) were linked to HIV treatment[5]. Of the 24 who reported reactive results in Akwa Ibom State, 87.5% had confirmatory testing, 100.0% reported confirmed HIV-positive results, and 100.0% were successfully linked to HIV care and treatment[5]. Another study reported that the 14 participants who had a reactive HIV self-test sought post-test counselling and had confirmatory HIV testing at the community health centre[35].

Dirisu et al[34] highlighted barriers to linkage to care, including concerns around post-test counselling services and linkage to confirmatory HIV testing services following reactive HIVST results. For instance, men who have sex with men (MSM) were concerned that because self-testers would be testing alone, many would deny their HIV-positive test results and may not seek HIV treatment. In another interview that sought the opinions of the public and that of stakeholders and policy makers on the introduction of HIVST in Nigeria, participants expressed concerns about how to link individuals who tested HIVST reactive to confirmatory HIV testing services and care and treatment services as in the facility-based testing model[27]. Obiezu-Umeh et al[32] highlighted the motivations to seek a confirmatory HIV test in the event of a reactive HIVST result to include encouragement from peers, family members, or healthcare workers, denial about the initial HIVST test result, lack of satisfaction with the test result, and the possibility of living longer if initiated on treatment and care.

Studies conducted among young people in Nigeria by Obiezu-Umeh et al[32] and Iwelunmor et al[36] reported that the cost of HIVST was the strongest determinant for choosing HIVST services. The cost of HIVST ranged from 200 to 4000 Naira (approximately United States Dollar 0.55-11.07). However, the majority of young people suggested 500 Naira (approximately United States Dollar 1.38) as the preferred cost of the kit. Young people argued that the high cost of HIVST remained a major barrier to uptake since most young people might not be willing to purchase the kit given that HIVST kits are available in some hospitals and non-governmental organizations either free of charge or at a subsidized rate[32].

Ong et al[33] and Obiezu-Umeh et al[32] reported access location as a major driver and the most influential driver, respectively, of HIVST uptake. Obiezu-Umeh et al[32] reported privately-owned facilities, registered pharmacies, youth-friendly centres, supermarkets, and online stores as the most cited preferred locations to access HIVST kits. Ong et al[33] added that the least influential driver of HIVST uptake was the type of specimen needed for HIVST. Obiezu-Umeh et al[32] and Iwelunmor et al[36] suggested making HIVST more appealing to young Nigerians. This could be achieved by repackaging existing HIVST products with colours, taglines, designs, and youth-friendly animations[32,36]. Iwelunmor et al[36] also found that providing instruction for use translated into the three most common Nigerian languages (Igbo, Hausa, and Yoruba) would further enhance the appeal and uptake of the product among diverse segments of youths in Nigeria.

Studies among young people, MSM, and KOLs recommended using social media (Facebook/SMS and WhatsApp, etc.) and bulk SMS messages to enhance the uptake of HIVST[36,37]. In contrast, a quantitative study among key populations in Nigeria reported that 85% of female sex workers and 68% of MSM preferred an in-person modality of receiving information on HIVST services[37]. Furthermore, Sekoni et al[37] further suggested using KOLs to distribute and enhance the uptake of HIVST kits among MSM. Similarly, Iwelunmor et al[36] opined that recruiting local celebrities to join HIVST online campaigns and endorse HIVST-related hashtags could generate high demand for HIVST services and promote its uptake among their teeming fans who are mostly young people.

HIVST is a rapidly growing HIV testing strategy that is gradually gaining acceptability globally. However, the level of acceptability and strategies to enhance the uptake of HIVST varies across different populations and settings. In this systematic review, we examined the acceptability of HIVST and strategies to enhance the uptake of HIVST in Nigeria. Our findings revealed a high level of acceptability of HIVST in most of the studies included in this systematic review with many citing privacy and convenience as key factors in their willingness to use the service[5,7,15,27-31,38]. These findings are consistent with previous studies, which reported high acceptability and ease of use of HIVST in other settings such as United States, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe[39-41].

For instance, a recent cross-sectional study conducted in Tanzania among medical students showed a high level of knowledge, acceptability, and willingness to use oral fluid HIVST[39]. Similarly, a recent survey among people who use illicit drugs in the United States reported high acceptability of an HIVST program, and 77% of study participants were willing to use HIVST kits regularly if available[40]. In addition, a campus-based distribution of oral HIVST was highly acceptable among young adult students in Zimbabwe, with 97.1% of participants indicating willingness to use oral HIV self-tests[41]. However, some studies have reported low acceptability for HIVST among specific populations, such as MSM in Brazil, where less than half (47.3%) were willing to use HIVST[42].

Cost was a significant barrier to HIV testing among young people in Nigeria, and they preferred free or low-cost testing services[26]. The cost of HIVST in the private sector, especially in low-income contexts, may contribute to an unwillingness to use HIVST, which justifies the need for free distribution to key and priority groups in the public sector. Additionally, the fear of getting a positive result without being appropriately linked to a health service could also contribute to low acceptance of HIVST, thus emphasizing the importance of a peer navigator to support clients across the continuum of care.

The uptake of HIVST and linkage to care services varies across different population groups and countries. This systematic review found a high uptake of HIVST among MSM in Nigeria, similar to findings from Bangkok, Thailand[35,43], while low uptake of HIVST has been reported in South Africa and China[44,45]. This variation in findings could be attributed to differences in the level of awareness about HIVST among the studied populations. Factors such as education level, age, marital status, and knowledge about HIV can also influence the uptake of HIVST[27,28,35,44-46].

A study conducted in the Republic of Congo reported a high linkage to HIV care services (82.2%) among individuals with a reactive result from HIVST, which is consistent with the findings of another study in Nigeria[47]. However, studies have highlighted several barriers to linkage to care, such as social stigma, lack of communication about the benefits of testing, and the referral process after testing, as well as a lack of a supportive peer network to encourage linkage after testing[27,28,48]. Therefore, it is important to identify and address these barriers to linkage to care to ensure that HIVST programs are effective in reducing the burden of HIV and promoting early diagnosis and treatment.

Further research is needed to develop interventions that address the barriers to uptake and linkage to care. The systematic review on strategies to enhance HIVST uptake shows the importance of accessible points of HIVST distribution and involvement of young people in the development and design of HIVST services to address their preferences, which include privacy, confidentiality, convenience, and assurance of accuracy in order to enhance uptake[32,33,36]. These findings are supported by studies from Rwanda[49,50] which suggested that involving the target population in program design could improve HIVST uptake. The co-creation process that involved men in Rwanda identified the need for a comprehensive health education program to address barriers to HIVST uptake. Key stakeholders emphasized the need for community engagement, regulatory frameworks, and sustained political commitment to promote the increase of HIVST.

Furthermore, this systematic review also highlighted additional strategies to enhance HIVST uptake in Nigeria, including increasing awareness, regulating the sale of self-test kits, subsidizing the cost of self-test kits, maintaining consistent availability of self-test kits, and documenting HIVST standards and policies[35,38,51,52]. The articles also suggested that mobilization campaigns, training for people involved in implementation, and engaging key stakeholders such as religious and community leaders, employers, KOLs, celebrities, and health workers could accelerate HIV testing and promote uptake and linkage to care services.

Overall, the findings suggested that tailored communication strategies that address misinformation, misconceptions, and mistrust about HIVST and pre-exposure prophylaxis are needed for improved uptake of HIVST among key populations in Nigeria[38]. The involvement of stakeholders and the target population can lead to the design of HIVST programs that address the unique needs and preferences of each population, ultimately improving HIV testing and linkage to care services[49].

In summary, the landscape of HIVST in Nigeria is still in its infancy with a limited evidence base. Therefore, there is a compelling need for more high-quality research such as randomized clinical trials to advance our understanding of HIVST. This study revealed a shortage of implementation science research, despite the various self-testing activities ongoing in Nigeria. The investigators also noted lack of studies evaluating other HIVST distribution models, such as workplace, community distribution, and distribution among facility providers, and sub-populations, like pregnant women, people who inject drugs, and female sex workers. Only one study from Southern Nigeria evaluated programmatic HIVST distribution data among CPs. While the acceptability of HIVST is generally high in Nigeria when measured from the intention-to-use perspective, actual use in programmatic implementation was lower, primarily due to the cost barrier among pharmacy retail outlets. Therefore, innovative financing approaches targeting different population segments are necessary for effective scaling and growth of the HIVST market in Nigeria using demand side subsidy financing, total market approach, and social marketing.

More controlled implementation studies are required to test the acceptability of HIVST. The use of KOLs among key populations has been successful in increasing the acceptability and uptake of HIVST. The uptake of HIVST was generally high among reported studies, except for reported HIVST results. Therefore, more studies are needed to evaluate factors responsible for poor uptake of HIVST result retrieval and how uptake will compare in routine programs vs real-life settings in the absence of support and resources that enhance HIVST uptake. In conclusion, despite limitations, this is the first systematic literature review of HIVST in Nigeria, providing valuable insights into the evidence base on the acceptability and uptake of HIVST in the country.

Nigeria has a high burden of human immunodeficiency (HIV)/acquired immune deficiency syndrome, and a significant proportion of infected individuals remain untested due to fear of stigma and discrimination. HIV self-testing (HIVST) is recommended by the World Health Organization as a tool for imp

To systematically review the acceptability, existing regulations, and strategies for enhancing the uptake of HIVST in Nigeria.

To fill a crucial gap in understanding the HIVST landscape in Nigeria and provide insights into the evidence base on the acceptability and uptake of HIVST in the country.

A systematic literature review was conducted, and 18 articles were included in the analysis.

The study found that the acceptability of HIVST is generally high in Nigeria from the intention-to-use perspective. However, the actual use of HIVST in programmatic implementation was lower than expected. The study recommends more controlled implementation studies to test the acceptability of HIVST and to explore factors responsible for poor uptake. The use of key opinion leaders among key populations has been found to be successful in increasing the acceptability and uptake of HIVST. However, cost remains a major barrier to the acceptability of HIVST among pharmacy retail outlets.

The present study provided crucial understanding of the HIVST landscape in Nigeria, which is young and evolving. The study highlighted the need for further high-quality research in this area and recommended innovative financing approaches targeting different population segments for effective scaling of HIVST under the total market approach.

More studies are required to evaluate how the uptake of HIVST compares in routine programs vs real-life settings in the absence of support and resources that enhance HIVST uptake. Overall, this study contributed to the current knowledge base on HIVST in Nigeria and highlighted the need for further high-quality research in this area.

The investigators want to acknowledge all authors who shared the full text of their manuscripts with us. The investigators also wish to acknowledge Dr. Akintayo Ogunwale and Dr. (Mrs.) Omotayo Sindiku for their time and intellectual contribution while reviewing this manuscript.

| 1. | Busari AA, Oshikoya KA, Akinwumi AF, Usman SO, Badru WA, Olusanya AW, Oreagba IA. Antiretroviral Therapy Related Problems among Human Immunodeficiency Virus infected Patients: A Focus on Medication Adherence and Pill Burden. Nigerian Journal of Medicine. 2021;30:282-287. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | USAID, 2019. New survey results indicate that Nigeria has an HIV prevalence of 1.4%. Abuja/Geneva. UNAIDS press release. 14 Mar 2019. [cited April 8, 2023]. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/pressreleaseandstatementarchive/2019/march/20190314_nigeria. |

| 3. | Adekunjo FO, Rasiah R, Dahlui M, Ng CW. Assessing the willingness to pay for HIV counselling and testing service: a contingent valuation study in Lagos State, Nigeria. Afr J AIDS Res. 2020;19:287-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ajayi A, Awopegba O, Owolabi E, Ajala A. Coverage of HIV testing among pregnant women in Nigeria: progress, challenges and opportunities. J Public Health (Oxf). 2021;43:e77-e84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Agada P, Ashivor J, Oyetola A, Usang S, Asuquo B, Nuhu T. Reaching out to the hard-to-reach populations with HIV self-testing services in South-south Nigeria. Journal of Pre-Clinical and Clinical Research. 2021;15:155-161. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kitara DL, Aloyo J. HIV/AIDS Stigmatization, the Reason for Poor Access to HIV Counseling and Testing (HCT) Among the Youths in Gulu (Uganda). Afr J Infect Dis. 2012;6:12-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Adebimpe WO, Ebikeme D, Omobuwa O, Oladejo E. How acceptable is the HIV/AIDS self-testing among women attending immunization clinics in Effurun, Southern Nigeria. Marshall J Med. 2019;5:37. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | World Health Organization. Guidelines on HIV self testing and partner notification: Supplement to consolidated guidelines on HIV testing services. Dec 2016. [cited September 26, 2022]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/251655/9789241549868-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. |

| 9. | Steehler K, Siegler AJ. Bringing HIV Self-Testing to Scale in the United States: a Review of Challenges, Potential Solutions, and Future Opportunities. J Clin Microbiol. 2019;57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sharma M, Barnabas RV, Celum C. Community-based strategies to strengthen men's engagement in the HIV care cascade in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS Med. 2017;14:e1002262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 135] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 18.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Harichund C, Moshabela M, Kunene P, Abdool Karim Q. Acceptability of HIV self-testing among men and women in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. AIDS Care. 2019;31:186-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hensen B, Taoka S, Lewis JJ, Weiss HA, Hargreaves J. Systematic review of strategies to increase men's HIV-testing in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS. 2014;28:2133-2145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hlongwa M, Mashamba-Thompson T, Makhunga S, Muraraneza C, Hlongwana K. Men's perspectives on HIV self-testing in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-synthesis. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Indravudh PP, Choko AT, Corbett EL. Scaling up HIV self-testing in sub-Saharan Africa: a review of technology, policy and evidence. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2018;31:14-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Iliyasu Z, Kassim RB, Iliyasu BZ, Amole TG, Nass NS, Marryshow SE, Aliyu MH. Acceptability and correlates of HIV self-testing among university students in northern Nigeria. Int J STD AIDS. 2020;31:820-831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Krause J, Subklew-Sehume F, Kenyon C, Colebunders R. Acceptability of HIV self-testing: a systematic literature review. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 256] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Choko AT, Desmond N, Webb EL, Chavula K, Napierala-Mavedzenge S, Gaydos CA, Makombe SD, Chunda T, Squire SB, French N, Mwapasa V, Corbett EL. The uptake and accuracy of oral kits for HIV self-testing in high HIV prevalence setting: a cross-sectional feasibility study in Blantyre, Malawi. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1001102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 267] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gaydos CA, Hsieh YH, Harvey L, Burah A, Won H, Jett-Goheen M, Barnes M, Agreda P, Arora N, Rothman RE. Will patients "opt in" to perform their own rapid HIV test in the emergency department? Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58:S74-S78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Carballo-Diéguez A, Frasca T, Dolezal C, Balan I. Will gay and bisexually active men at high risk of infection use over-the-counter rapid HIV tests to screen sexual partners? J Sex Res. 2012;49:379-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Patino CM, Ferreira JC. Inclusion and exclusion criteria in research studies: definitions and why they matter. J Bras Pneumol. 2018;44:84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12275] [Cited by in RCA: 13049] [Article Influence: 435.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 22. | Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, Leeflang MM, Sterne JA, Bossuyt PM; QUADAS-2 Group. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:529-536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6953] [Cited by in RCA: 10409] [Article Influence: 693.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 23. | Singh J. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, CASP Appraisal Tools. J. Pharm. Pharmacol.. 2013;4:76. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wright AP, Fox AN, Johnson KG, Zinn K. Systematic screening of Drosophila deficiency mutations for embryonic phenotypes and orphan receptor ligands. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Cuschieri S. The STROBE guidelines. Saudi J Anaesth. 2019;13:S31-S34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 387] [Cited by in RCA: 2639] [Article Influence: 377.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 26. | Nwaozuru U, Iwelunmor J, Ong JJ, Salah S, Obiezu-Umeh C, Ezechi O, Tucker JD. Preferences for HIV testing services among young people in Nigeria. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:1003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Brown B, Folayan MO, Imosili A, Durueke F, Amuamuziam A. HIV self-testing in Nigeria: public opinions and perspectives. Glob Public Health. 2015;10:354-365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Dirisu O, Sekoni A, Vu L, Adebajo S, Njab J, Shoyemi E, Ogunsola S, Tun W. 'I will welcome this one 101%, I will so embrace it': a qualitative exploration of the feasibility and acceptability of HIV self-testing among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Lagos, Nigeria. Health Educ Res. 2020;35:524-537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Ugwu GO, Ochie CN, Asogwa TC, Onah CK, Enebe NO, Ezema GU. Human immunodeficiency virus self-testing: Perspectives from primary healthcare workers in Enugu state, southeast Nigeria. Nigerian Journal of Medicine. 2020;29:504-510. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Adeoti AO, Desalu OO, Oluwadiya KS. Sexual practices, risk perception and HIV self-testing acceptability among long-distance truck drivers in Ekiti State, Nigeria. Niger Postgrad Med J. 2021;28:273-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 31. | Iliyasu Z, Galadanci HS, Musa AH, Iliyasu BZ, Nass NS, Garba RM, Jibo AM, Okekenwa SC, Salihu HM, Aliyu MH. HIV self-testing and repeat testing in pregnancy and postpartum in Northern Nigeria. Trop Med Int Health. 2022;27:110-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Obiezu-Umeh C, Gbajabiamila T, Ezechi O, Nwaozuru U, Ong JJ, Idigbe I, Oladele D, Musa AZ, Uzoaru F, Airhihenbuwa C, Tucker JD, Iwelunmor J. Young people's preferences for HIV self-testing services in Nigeria: a qualitative analysis. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Ong JJ, Nwaozuru U, Obiezu-Umeh C, Airhihenbuwa C, Xian H, Terris-Prestholt F, Gbajabiamila T, Musa AZ, Oladele D, Idigbe I, David A, Okwuzu J, Bamidele T, Iwelunmor J, Tucker JD, Ezechi O. Designing HIV Testing and Self-Testing Services for Young People in Nigeria: A Discrete Choice Experiment. Patient. 2021;14:815-826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Dirisu O, Ilesanmi O, Akinola A, Adediran M, Tun W, Mpazanje R. Exploring the regulatory context for HIV self-testing and PrEP market authorisation and use in Nigeria. HIV and AIDS. 2021;. |

| 35. | Tun W, Vu L, Dirisu O, Sekoni A, Shoyemi E, Njab J, Ogunsola S, Adebajo S. Uptake of HIV self-testing and linkage to treatment among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Nigeria: A pilot programme using key opinion leaders to reach MSM. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21 Suppl 5:e25124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Iwelunmor J, Ezechi O, Obiezu-Umeh C, Gbaja-Biamila T, Nwaozuru U, Oladele D, Musa AZ, Idigbe I, Uzoaru F, Airhihenbuwa C, Muessig K, Conserve DF, Kapogiannis B, Tucker JD. The 4 youth by youth HIV self-testing crowdsourcing contest: A qualitative evaluation. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0233698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Sekoni A, Tun W, Dirisu O, Ladi-Akinyemi T, Shoyemi E, Adebajo S, Ogunsola F, Vu L. Operationalizing the distribution of oral HIV self-testing kits to men who have sex with men (MSM) in a highly homophobic environment: the Nigerian experience. BMC Public Health. 2022;22:33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Durosinmi-Etti O, Nwala EK, Oki F, Ikpeazu A, Godwin E, Umoh P, Shaibu A, Ogundipe A, Kalaiwo A. Communication needs for improved uptake of PrEP and HIVST services among key populations in Nigeria: a mixed-method study. AIDS Res Ther. 2021;18:88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Vara PA, Buhulula LS, Mohammed FA, Njau B. Level of knowledge, acceptability, and willingness to use oral fluid HIV self-testing among medical students in Kilimanjaro region, Tanzania: a descriptive cross-sectional study. AIDS Res Ther. 2020;17:56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Peiper NC, Shamblen S, Gilbertson A, Guest G, Kopp M, Guy L, Rose MR. Acceptability of a HIV self-testing program among people who use illicit drugs. Int J Drug Policy. 2022;103:103613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Koris AL, Stewart KA, Ritchwood TD, Mususa D, Ncube G, Ferrand RA, McHugh G. Youth-friendly HIV self-testing: Acceptability of campus-based oral HIV self-testing among young adult students in Zimbabwe. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0253745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Magno L, Leal AF, Knauth D, Dourado I, Guimarães MDC, Santana EP, Jordão T, Rocha GM, Veras MA, Kendall C, Pontes AK, de Brito AM, Kerr L; Brazilian HIV/MSM Surveillance Group. Acceptability of HIV self-testing is low among men who have sex with men who have not tested for HIV: a study with respondent-driven sampling in Brazil. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20:865. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Phongphiew P, Songtaweesin WN, Paiboon N, Phiphatkhunarnon P, Srimuan P, Sowaprux T, Wongharn P, Moonwong J, Kawichai S, Puthanakit T. Acceptability of blood-based HIV self-testing among adolescents aged 15-19 years at risk of HIV acquisition in Bangkok. Int J STD AIDS. 2021;32:927-932. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Awopegba OE, Ologunowa TO, Ajayi AI. HIV testing and self-testing coverage among men and women in South Africa: an exploration of related factors. Trop Med Int Health. 2021;26:214-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Liu Y, Wu G, Lu R, Ou R, Hu L, Yin Y, Zhang Y, Yan H, Zhao Y, Luo Y, Ye M. Facilitators and Barriers Associated with Uptake of HIV Self-Testing among Men Who Have Sex with Men in Chongqing, China: A Cross-Sectional Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Li J, Marley G, Zhang Y, Chen Y, Tang W, Rongbin Y, Fu G. Determinants of Recent HIV Self-Testing Uptake Among Men Who Have Sex With Men in Jiangsu Province, China: An Online Cross-Sectional Survey. Front Public Health. 2021;9:736440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Tonen-Wolyec S, Kayembe Tshilumba C, Batina-Agasa S, Tagoto Tepungipame A, Bélec L. Uptake of HIV/AIDS Services Following a Positive Self-Test Is Lower in Men Than Women in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:667732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Harrison L, Kumwenda M, Nyirenda L, Chilongosi R, Corbett E, Hatzold K, Johnson C, Simwinga M, Desmond N, Taegtmeyer M. "You have a self-testing method that preserves privacy so how come you cannot give us treatment that does too?" Exploring the reasoning among young people about linkage to prevention, care and treatment after HIV self-testing in Southern Malawi. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22:395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Dzinamarira T, Mulindabigwi A, Mashamba-Thompson TP. Co-creation of a health education program for improving the uptake of HIV self-testing among men in Rwanda: nominal group technique. Heliyon. 2020;6:e05378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Dzinamarira T, Kamanzi C, Mashamba-Thompson TP. Key Stakeholders' Perspectives on Implementation and Scale up of HIV Self-Testing in Rwanda. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Obiezu-Umeh C, Gbajabiamila T, Nwaozuru U, Uzoaru F, Mason S, Oladele D, Idigbe I, Musa A, Conserve D, Nkengasong S, Airhihenbuwa C, Ezechi O, Tucker J, Iwelunmor J. Development of HIV self-testing services through youth engagement: a qualitative evaluation of a health designathon in Nigeria. Lancet Glob. Health. 2020;8:S15. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Iwelunmor J, Ezechi O, Obiezu-Umeh C, Gbaja-Biamila T, Musa AZ, Nwaozuru U, Xian H, Oladele D, Airhihenbuwa CO, Muessig K, Rosenberg N, Conserve DF, Ong JJ, Nkengasong S, Day S, Tahlil KM, BeLue R, Mason S, Tang W, Ogedegbe G, Tucker JD. Enhancing HIV Self-Testing Among Nigerian Youth: Feasibility and Preliminary Efficacy of the 4 Youth by Youth Study Using Crowdsourced Youth-Led Strategies. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2022;36:64-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medical laboratory technology

Country/Territory of origin: Nigeria

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Liu D, China; Zhu C, China S-Editor: Liu XF L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Ju JL