Published online Dec 25, 2025. doi: 10.5527/wjn.v14.i4.112066

Revised: August 18, 2025

Accepted: November 21, 2025

Published online: December 25, 2025

Processing time: 160 Days and 0 Hours

Background diabetic nephropathy (DN), a major complication of diabetes, is linked to gut microbiota dysbiosis. Elevated trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO), a microbiota-derived metabolite, plays a central role in inducing renal injury during DN pathogenesis.

To investigate the role of TMAO in renal dysfunction and intestinal microbiota alterations associated with DN, hypothesizing that TMAO exacerbates renal injury and fibrosis through gut microbiota-dependent mechanisms.

A DN model was successfully established using Zucker diabetic fatty (ZDF) rats. Blood samples were analyzed for renal function parameters, and serum TMAO levels were quantified via high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Renal tissue morphology and fibrosis were assessed using hema

After 8 weeks of modeling, the ZDF rat model group exhibited blood glucose levels surpassing 16.7 mmol/L, and compared to the control group, renal function indicators, including β2-microglobulin, cystatin C, uric acid, and creatinine, were significantly elevated (P < 0.05). Renal fibrosis was more pronounced in the ZDF model group, accompanied by heightened P-smad3 expression, in contrast to the TMAO inhibition group. Although Masson staining results did not reach stati

DN is associated with gut microbiota alterations that potentiate TMAO generation, contributing to renal injury and fibrotic progression. While TMAO’s role in fibrosis warrants further validation, these findings implicate the gut-kidney axis in DN pathogenesis.

Core Tip: Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is characterized by significant renal dysfunction and gut microbiota dysbiosis, which enhances the microbiota’s capacity to produce trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO). In Zucker diabetic fatty rats, elevated TMAO levels were associated with aggravated renal injury, fibrosis, and upregulated P-smad3 expression. Fecal microbiota transplantation from DN rats further increased TMAO production, confirming TMAO as a key microbiota-derived mediator in DN progression.

- Citation: Song YJ, Yang B, Feng QS, Ma FF, Xing B, Bin XL, Ha XQ. Gut microbiota-derived trimethylamine N-oxide exacerbates diabetic nephropathy by promoting renal fibrosis. World J Nephrol 2025; 14(4): 112066

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-6124/full/v14/i4/112066.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5527/wjn.v14.i4.112066

Diabetes mellitus is a multifaceted metabolic disorder influenced by both environmental and genetic factors. In 2017, the global diabetic population stood at approximately 425 million, with China reporting a prevalence rate of 10.9%. This number is projected to soar to 629 million[1]. As the diabetic patient population continues to grow and preventive and therapeutic interventions remain inadequate, the complications of diabetes mellitus, particularly diabetic nephropathy (DN), increasingly compromise patients’ quality of life and survival. Notably, DN affects roughly one-third of diabetic individuals[2], emerging as the leading cause of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and the most prevalent contributor to end-stage renal disease.

The human gastrointestinal tract constitutes a vast microbial ecosystem and gene repository, harboring trillions of microbial cells[3], and plays a pivotal role in the maturation and stabilization of the host immune system, safeguarding against pathogen overgrowth, influencing host cell proliferation as well as vascularization, and regulating enteroendocrine functions. Our research has revealed significant alterations in the intestinal flora of diabetic rat models. Furthermore, existing literature supports that kidney function changes can impact the intestinal flora structure[4]. Such structural shifts in the intestinal flora directly influence the synthesis of key metabolites, including short-chain fatty acids, decyl sulfate, and p-cresol sulfate. Trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) appears to occupy a central “hub” position in the interplay between DN and intestinal microecology.

TMAO, a compound that has garnered increasing attention in recent years, circulates in the bloodstream and is closely linked to CKD and cardiovascular conditions. Elevated TMAO levels are particularly prominent in patients suffering from obesity, diabetes, and kidney impairment[5]. TMAO is primarily generated from the dietary conversion of choline[5], which is first metabolized by gut bacteria into trimethylamine[6]. Trimethylamine is then absorbed into the bloodstream, where it is oxidized by liver monooxygenase to form TMAO[7]. Choline, abundant in foods like eggs and liver and present to some extent in most foods[8], exists in food as both free choline and choline ester[9]. These forms are absorbed differently by the intestine: Free choline via active transport, and choline esters through the lymphatic system, where they are either absorbed directly or hydrolyzed by pancreatic lipase before being absorbed as glycerol phosphate choline[10]. Due to its small molecular weight, TMAO is easily filtered and secreted in the proximal tubules. Following the administration of radiolabeled TMAO, studies have shown that 94.5% of it is excreted in the urine within 24 hours, with only 4% excreted in feces and 1% through the respiratory system[11]. Initially, it was believed that TMAO was solely acquired through dietary intake, overlooking the crucial role of intestinal microbes, but sterile mice studies have demonstrated that TMAO synthesis is inhibited in the absence of microbial metabolism of trimethylamine[12,13]. Notably, no research, either domestic or international, has thoroughly explored the relationship between intestinal microecology and TMAO in the context of DN, and insufficient attention has been paid to alterations in the intestinal flora during the progression of DN. The significance of these relationships requires further exploration to better understand and potentially manage DN.

To investigate the relationship between intestinal flora changes, blood TMAO levels, and TMAO-induced renal damage in DN, this study employed 16S rRNA sequencing technology to analyze DN in rats. Changes in the bacterial flora and blood TMAO concentrations were observed, and the capacity of TMAO to induce DN was utilized by fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). Furthermore, bioinformatics approaches were applied to assess the potential of intestinal bacterial group-based biomarkers, thereby establishing a robust theoretical foundation for therapeutic strategies. Finally, cellular experiments were conducted to elucidate the underlying mechanism of TMAO-induced kidney injury.

Twelve male Zucker diabetic fatty (ZDF) rats (fa/fa, leptin receptor-deficient), aged 8 weeks, weighing 240-260 g, and twelve male ZDF control rats (fa/+, normal leptin receptor), aged 8 weeks, weighing 190-210 g, were purchased from Beijing Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. [License No. SCXK (Jing) 2016-0011; Certification No. 11400700242853]. The rats were housed in the Animal Experiment Department of the 940th Hospital of the Joint Logistics Support Force under the following conditions: Single-cage housing, weekly bedding replacement, temperature maintained at 21-26 °C, 12/12 hours light/dark cycle, and relative humidity of 50%-80%. They were fed with Purina #5008 diet (crude protein 23.5%, crude fat 6.5%) purchased from Yongli (Shanghai) Biotechnology Co., Ltd., with free access to food and water.

Additionally, twelve male BALB/c mice, aged 4 weeks and weighing 13-15 g, were obtained from the Animal Experiment Department of the 940th Hospital of the Joint Logistics Support Force [License No. SCXK (Jun) 2012-0029]. The mice were housed under the same conditions (single-cage housing, weekly bedding replacement) and provided with a standard diet and free access to food and water.

Starting from the initiation of the DN rat model, blood glucose levels and body weights of the rats were monitored weekly using a blood glucose meter. Following 2 weeks of specific dietary feeding, a notable increase in blood glucose levels was observed; by the fourth week, levels exceeded 16.7 mmol/L and remained elevated in some rats through the eighth week, resulting in significant kidney damage. A blood glucose level exceeding 16.7 mmol/L at the fourth week of model development served as an indicator of successful DN rat model establishment. By the eighth week, in contrast to the renal tissue of the C1 group (ZDF normal rats), the renal tissue of the E1 group (ZDF diabetes model rats) exhibited distinct pathological changes. The DN model was deemed successfully established when renal injury and serum renal function indicators were significantly increased.

Prior to FMT, mice were individually housed in separate cages with a 1-week acclimation period, during which cages were systematically rotated to maintain microbial homogeneity among animals. Following acclimation, the mice were stratified into experimental and control groups, and baseline fecal samples were collected and designated as experimental group before transplantation group and control group before transplantation group. To deplete indigenous gut microbiota, mice received a 1-week course of non-absorbable broad-spectrum antibiotics in drinking water (0.5 g/L vancomycin, 1 g/L ampicillin, 1 g/L metronidazole, and 1 g/L neomycin sulfate). For FMT procedures, twelve BALB/c mice were randomly allocated to experimental or control groups. Fresh fecal samples (0.1 g) from donor mice (E1 group for experimental recipients, C1 group for controls) were homogenized in 1.5 mL phosphate buffered solution, centrifuged, and the supernatant was administered via oral gavage for 7 consecutive days. Prior to each transplantation, gastric acid was neutralized with sodium bicarbonate to ensure microbial viability. One week post-FMT completion, fecal samples were collected and designated as post-FMT experimental and control groups, while blood samples were simultaneously obtained for TMAO quantification.

Serum samples (40 μL) were mixed with a 2-3-fold volume of acetonitrile at 4 °C, followed by the addition of 80 μL of a 10 μmol/L internal standard solution containing d9-TMAO. The mixture was then centrifuged at 12000 r/minute for 10 minutes, and the supernatant was collected for analysis. The following analytical parameters were employed: Stationary phase, Ultimate SiO2 column (2.1 mm × 100 mm, 5 μm; Wechmaterials, Inc.); mobile phase, acetonitrile: 10 mmol/ammonium formate (pH 3.0) in a 70%:30% (volume/volume) ratio, under isocratic elution conditions; flow rate, 0.4 mL/min; injection volume, 5 μL; column temperature, 30 °C; ion source, electrospray ionization; dry gas temperature, 300 °C; nebulizing gas (N2) flow rate, 8 L/minute; scanning method, multiple reaction monitoring for both quantitative and qualitative ion transitions.

At the start of the experiment, all mice were four weeks old. A cohort of 20 mice underwent a one-week treatment regimen with broad-spectrum, poorly absorbed antibiotics: Vancomycin (100 mg/kg), neomycin sulfate (200 mg/kg), metronidazole (200 mg/kg), and ampicillin (200 mg/kg). Following this pretreatment, the mice were randomly assigned to two groups. Both groups received FMT with fecal samples sourced from either patients with CKD or healthy controls. To ensure distinct microbial environments, the two groups of mice were housed in separate isolators while maintaining consistent microbial conditions. Fecal samples were collected from 10 randomly selected CKD rats and 10 healthy controls. Each fecal sample (0.1 g) was suspended in 1.5 mL of reduced sterile phosphate-buffered saline, and equal volumes of the donor suspensions were combined to create pooled mixtures. For one week, samples were collected from adult (five-week-old) male C57BL/6 mice that had been treated with antibiotics and received FMT from CKD rats or healthy controls. The fecal suspension was centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 10 minutes, and the supernatant was collected. Each mouse received 200 μL of the supernatant via intragastric administration once daily for one week. On day three post-FMT, plasma samples were collected from the mice and immediately stored at -80 °C for further analysis.

Western blotting was employed to detect phosphorylated P-smad3 proteins, known for their rapid expression. Protein extraction was performed using radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer lysis buffer supplemented with phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride and a protein phosphatase inhibitor cocktail, following the manufacturer’s guidelines. The protein concentration was precisely quantified using a bicinchoninic acid assay protein assay kit and subsequently normalized across samples. Then, 10 μL of the normalized protein samples were resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Following thorough washing, the membranes were exposed, and the gray values of the bands were analyzed to quantify protein expression levels.

Statistical analyses were conducted utilizing one-way analysis of variance followed by least significant difference t-tests, with SPSS 22.0 and GraphPad Prism 6.0 software. Statistical significance was indicated when P < 0.05.

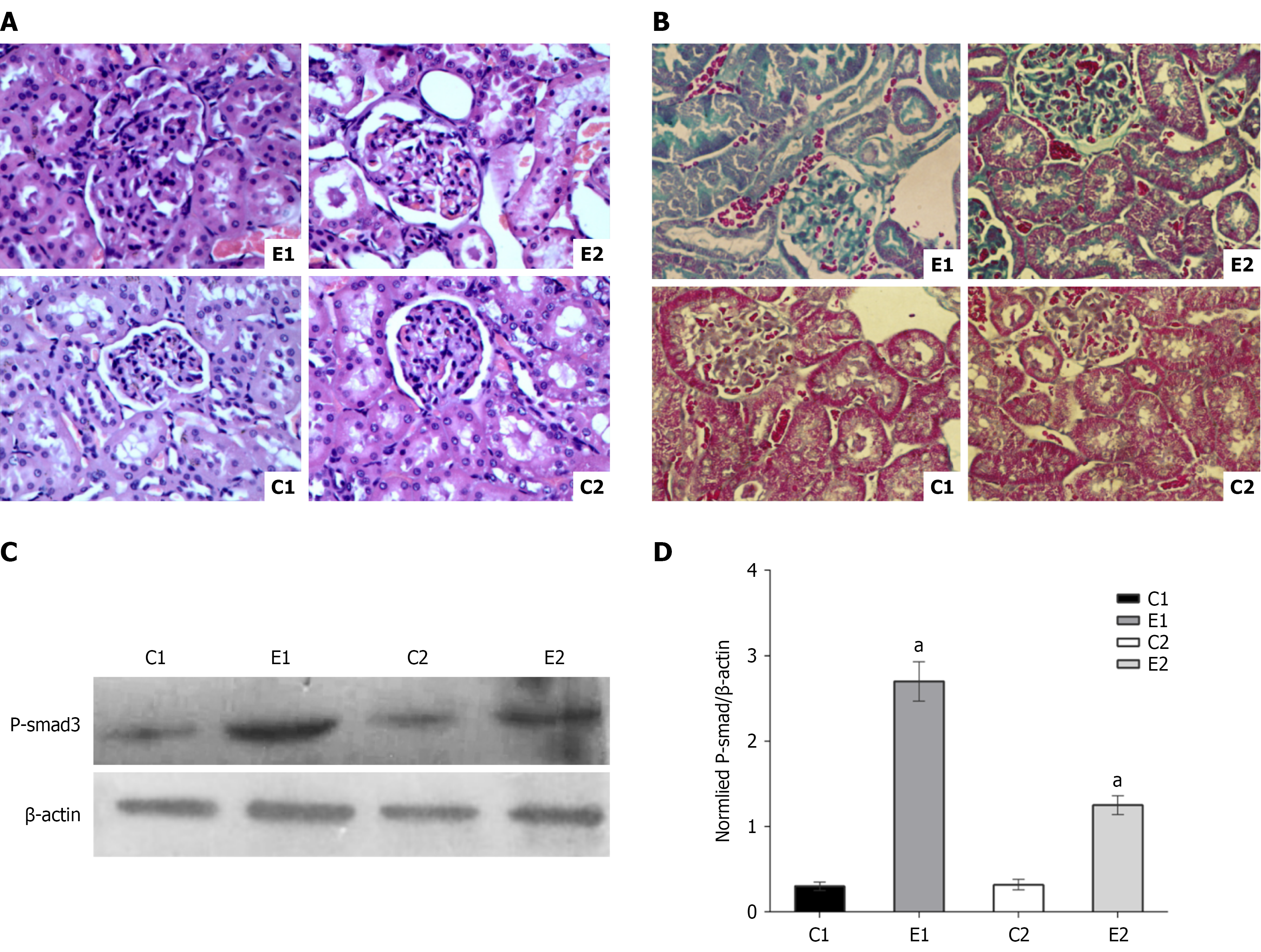

Rats were categorized into four distinct groups: C1 (ZDF normal rats), E1 (ZDF diabetes model rats), C2 [ZDF normal rats treated with 3,3-dimethyl-1-butanol (DMB) to inhibit intestinal TMAO production], and E2 (ZDF diabetes model rats treated with DMB). Following an 8-week modeling period, kidney function indicators and TMAO levels were assessed, with results detailed in Table 1. Renal tissues were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and structural changes were examined, as depicted in Figure 1A. Notably, the E1 group exhibited the most pronounced renal structural damage, while the E2 group exhibited partial damage, and the C1 and C2 groups maintained normal renal structure.

| Groups | Renal function index | ||||

| β2-microglobulin (mg/L) | Cystatin C (mg/L) | Uric acid (μmol/L) | Creatinine (μmol/L) | TMAO (mmol/L) | |

| C1 | 0.03 ± 0.002 | 0.02 ± 0.005 | 88.4 ± 3.2 | 41.2 ± 2.1 | 6.2 ± 0.3 |

| E1 | 0.18 ± 0.03a | 1.73 ± 0.1a | 142.8 ± 6.3a | 55.3 ± 3.6a | 14.6 ± 2.1a |

| C2 | 0.03 ± 0.003 | 0.03 ± 0.008 | 82.5 ± 6.5 | 40.1 ± 1.6 | 3.2 ± 0.3 |

| E2 | 0.10 ± 0.02a,b | 1.03 ± 0.07a,b | 113.5 ± 5.1a,b | 49.7 ± 2.5a,b | 10.3 ± 1.5a,b |

Diabetic kidney disease is strongly associated with renal fibrosis. To further assess this, renal fibrosis was evaluated using Masson staining and by detecting the P-smad3 protein in kidney tissue. The results are illustrated in Figure 1B-D. Masson staining revealed significantly more intense fibrosis in the E1 group compared to the other groups. The E1 group exhibited slightly more glomerular fibrosis than the E2 group and significantly increased renal tubular fibrosis relative to the E2 group. No notable fibrosis was observed in the C1 and C2 groups. The results for P-smad3 protein detection paralleled these observations.

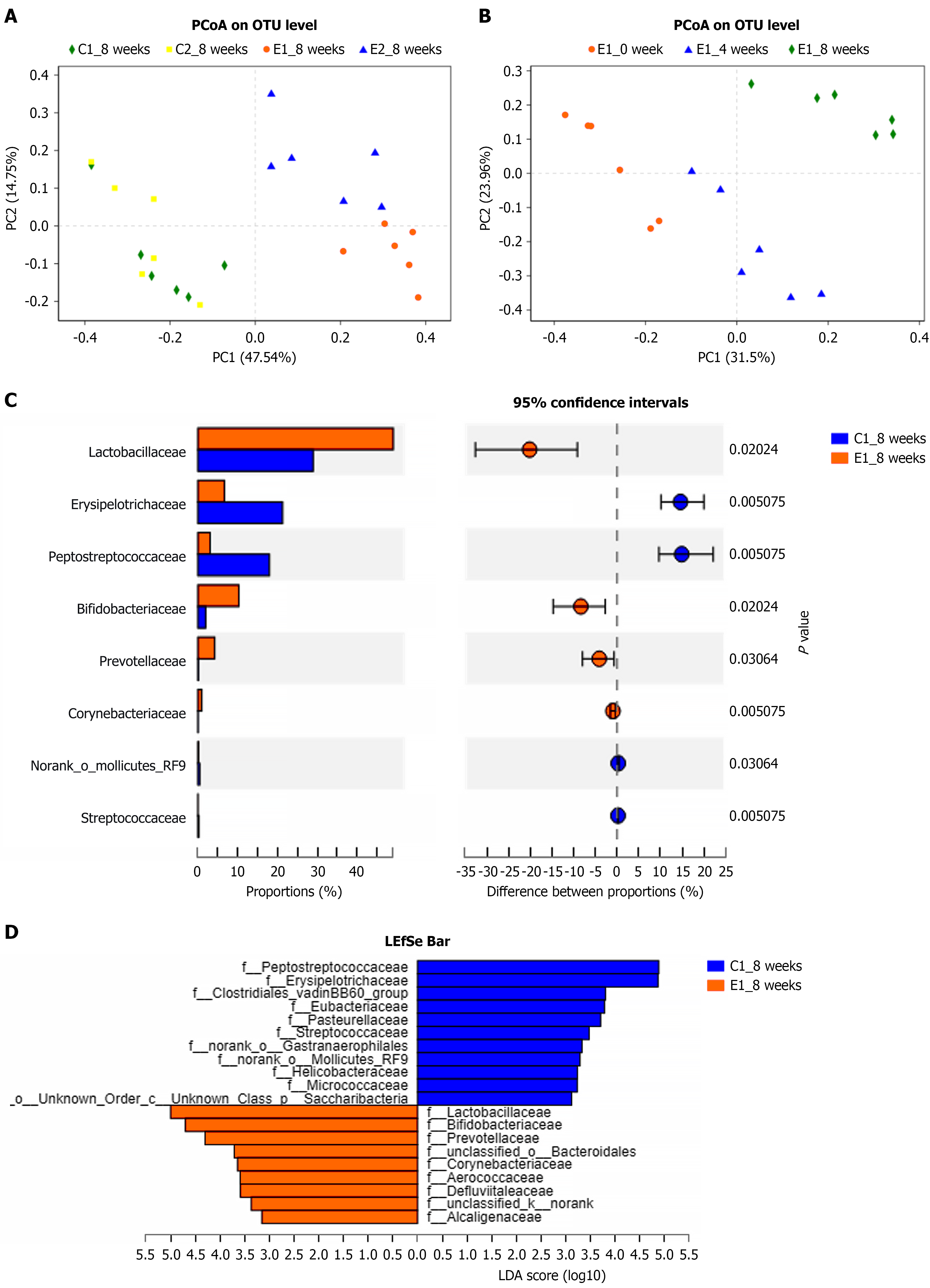

The principal coordinate analysis results at the 8th week, following the successful establishment of the DN rat model, are depicted in Figure 2A. Notably, there were significant differences in the intestinal bacterial compositions between the E1 and E2 groups, with clear separation of samples within these groups. The colony compositions in the C1 and C2 groups were similar, and the intestinal flora of rats in the E1 group underwent notable changes during modeling, as illustrated in Figure 2B.

The results of the level difference test between the E1 and C1 groups at the 8th week of modeling, analyzed using linear discriminant analysis effect size revealed significant enrichment of specific bacterial genera in the stool samples, and the Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, and Prevotellaceae genera were significantly more enriched in the E1 group compared to the C1 group; conversely, Peptostreptococcaceae and Erysipelotrichaceae were more prevalent in the C1 group samples. As depicted in Figure 2C and D, the comparison of differential flora between the two groups suggests that these particular bacteria are associated with the onset of DN in rats.

Through a screening of intestinal flora biomarkers, samples were categorized into normal, diabetic, and DN groups. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis is presented in Figure 3A. The area under the ROC curve for distinguishing between the normal and DN groups was 0.93 (Figure 3A). When comparing the diabetic and normal groups, the area under the ROC curve was 0.83 (Figure 3B), and for the diabetic and DN groups, it was 0.64 (Figure 3C). These findings indicate that the intestinal flora is a promising biomarker for differentiating among healthy people, diabetic patients, and those with DN.

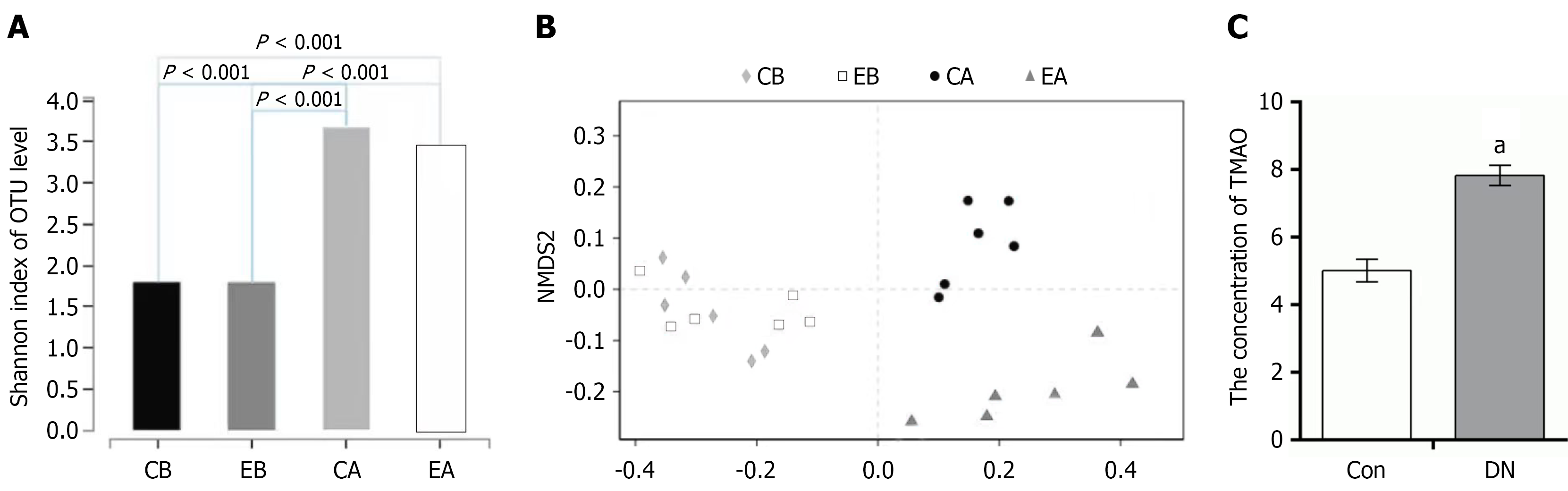

To assess the quality of sequencing data obtained from bacteria before and after transplantation, the coverage of the sequencing results was determined. The α diversity coverage index at the operational taxonomic unit (OTU) level was employed for analysis, with results depicted in Figure 4A. Samples were categorized into four groups: Pretransplant control (CB), pretransplant experimental (EB), posttransplant control (CA), and posttransplant experimental (EA). No significant difference in species diversity was observed between the CB and EB groups (P > 0.05), but the CB group exhibited significantly lower diversity compared to the CA group, and the EB group showed significantly lower diversity than the EA group (P < 0.001). Overall, bacterial diversity in both the CB and EB groups was lower than that in their respective posttransplant counterparts, the CA and EA groups.

Species differences before and after transplantation were assessed using partial least squares-discriminant analysis, with results illustrated in Figure 4B. Prior to transplantation, the intestinal flora exhibited relatively minor differences. Following transplantation, the experimental and the control groups demonstrated similar changes in species diversity to those observed in the pretransplant flora. The TMAO content in the sera of the transplanted rats was then examined, with results shown in Figure 4C. The TMAO levels in the experimental group’s intestinal flora were significantly elevated compared to those in the control group post-transplantation (P < 0.01).

Previous studies have consistently identified TMAO as a biomarker for kidney damage, but the biological activity of TMAO itself and its direct impact on renal injury remain underexplored. Clinical studies have revealed a negative correlation between TMAO levels and renal function in patients with CKD, with serum TMAO content serving as a predictor for the five-year survival rate of uremic patients[14]. Even among patients with normal renal function, elevated TMAO levels stemming from diverse causes are linked to various kidney diseases[15], and urinary TMAO concentration correlates significantly with tubulointerstitial lesions. Despite the extensive clinical investigations, research into the in vivo and in vitro effects of TMAO on kidney injury, as well as the underlying mechanisms, remains scarce.

In this study, TMAO was employed to evaluate kidney damage in a DN animal model. TMAO is primarily excreted via the kidneys, and a decline in renal function inevitably leads to its significant accumulation in the body, exacerbating illness. In DN, diabetes elevates blood TMAO levels, which further increase with diabetic renal dysfunction. This study is pioneering in determining alterations in TMAO content within a DN animal model, revealing increased TMAO levels during DN. Furthermore, increased TMAO was demonstrated to induce kidney damage and renal fibrosis, a critical mechanism affecting renal function in DN. Renal fibrosis represents the most prevalent pathological manifestation of end-stage renal disease from all causes and serves as a reliable predictor of DN progression to end-stage renal failure[16]. Choline, the precursor to DMB and TMAO, shares structural similarities with TMAO and can inhibit its formation. In this study, administering 1% DMB in drinking water reduced blood TMAO formation, a finding also verified in DN. DMB may exert protective effects against TMAO-induced damage and warrants further investigation, and Wang et al[6] reported no side effects in mice given DMB-containing drinking water for 16 weeks. However, further experimental or clinical studies are needed to validate these results, as the toxic side effects of DMB warrant attention while exploring its renal protective effects.

This experiment further analyzed the rats’ intestinal flora, often referred to as the “second genome” in humans due to its remarkable metabolic capacity and significant influence on various diseases. Our study focused on the intestinal flora of normal control, diabetic, and DN groups. Notably, DMB had minimal impact on the intestinal flora composition, but significant differences emerged between the DN group (E1) and the normal control group (C1), closely linked to the diabetic state and renal function damage. Differences were also evident between the C1 and C2 groups, reflecting the diabetic condition and mild kidney damage. The intestinal flora disparities between the E1 and E2 groups, both sharing the same diabetic pathogenesis, were striking. Despite similar blood sugar levels and body weights, the intestinal flora differences were attributed to variations in renal function. This finding underscores the influence of kidney function on intestinal flora composition. Further investigation through FMT revealed that the fecal flora from the E1 group produced more TMAO than that from the C1 group post-transplantation, indicating that alterations in intestinal flora in DN can lead to changes in blood TMAO levels, subsequently causing kidney damage. Importantly, the relationship between kidney damage and intestinal microbes is bidirectional: DN affects intestinal microbes, and microbial dysbiosis plays a key role in DN progression, further exacerbating the disease. DN induces dysbacteriosis, and flora changes further elevate blood TMAO levels, leading to increased renal fibrosis and renal function decline. As renal function deteriorates, the proportion of TMAO-producing bacteria rises, causing TMAO accumulation in the body and forming a vicious circle. The intestinal flora serves as a link between the intestines and kidneys, a relationship termed the “enteric-renal axis”.

In-depth analysis of intestinal flora and selection of DN biomarkers in the intestinal flora were conducted. By averaging the OTU counts across samples and focusing on the top ten species with the highest abundance, it is revealed that the diagnostic value for DN surpassed that for diabetes, with OTU values of 0.93 and 0.83, respectively. For clinical differentiation between diabetes and DN, the area under the ROC curve was 0.64, indicating a need to enhance accuracy by expanding the sample size or incorporating more species to minimize false positives and negatives. Differential flora analysis enables the screening of various disease states. Although this area of research is relatively new, Zeller et al[17] have previously explored diagnostic biomarkers using metagenomic genome sequence data to characterize the flora in colorectal cancer patients. Their detection accuracy was comparable to that of a standard fecal occult blood test, and combining the two methods increased sensitivity by 45% compared to fecal occult blood test alone, while maintaining specificity.

This study has certain limitations. Firstly, it did not directly investigate the impact of TMAO on renal cell fibrosis or confirm its definitive role in inducing glomerular and tubular fibrosis in the kidneys, necessitating further research for validation. Secondly, metagenomic sequencing was not employed to analyze the functional aspects of the intestinal flora, highlighting the need for more in-depth exploration of functional genomic changes in the TMAO-associated flora. Third, while the study results described alterations in the gut microbiota, they failed to specifically identify which bacterial taxa were affected and did not establish the correlations between these bacterial changes and clinical indicators of DN. However, this study is pioneering in reporting that TMAO contributes to kidney damage in DN, laying the foundation for further study of the mechanisms of TMAO-specific injury and the prevention of DN.

DN is associated with gut microbiota alterations that potentiate TMAO generation, contributing to renal injury and fibrotic progression. While TMAO’s role in fibrosis warrants further validation, these findings implicate the gut-kidney axis in DN pathogenesis.

We thank our competent technicians for their diligent and accurate work during the data-collection process. We would also like to thank the staff at the Microbiology Laboratory, the 940th Hospital, for consecutively including cases and sending registration forms to physicians treating patients in the wards.

| 1. | Ogurtsova K, da Rocha Fernandes JD, Huang Y, Linnenkamp U, Guariguata L, Cho NH, Cavan D, Shaw JE, Makaroff LE. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Global estimates for the prevalence of diabetes for 2015 and 2040. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2017;128:40-50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2306] [Cited by in RCA: 2599] [Article Influence: 288.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 2. | Reutens AT, Atkins RC. Epidemiology of diabetic nephropathy. Contrib Nephrol. 2011;170:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lin S, Wang Z, Lam KL, Zeng S, Tan BK, Hu J. Role of intestinal microecology in the regulation of energy metabolism by dietary polyphenols and their metabolites. Food Nutr Res. 2019;63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chu C, Behera TR, Huang Y, Qiu W, Chen J, Shen Q. Research progress of gut microbiome and diabetic nephropathy. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024;11:1490314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Subramaniam S, Fletcher C. Trimethylamine N-oxide: breathe new life. Br J Pharmacol. 2018;175:1344-1353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wang Z, Roberts AB, Buffa JA, Levison BS, Zhu W, Org E, Gu X, Huang Y, Zamanian-Daryoush M, Culley MK, DiDonato AJ, Fu X, Hazen JE, Krajcik D, DiDonato JA, Lusis AJ, Hazen SL. Non-lethal Inhibition of Gut Microbial Trimethylamine Production for the Treatment of Atherosclerosis. Cell. 2015;163:1585-1595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1160] [Cited by in RCA: 1017] [Article Influence: 92.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fouque D, Cruz Casal M, Lindley E, Rogers S, Pancířová J, Kernc J, Copley JB. Dietary trends and management of hyperphosphatemia among patients with chronic kidney disease: an international survey of renal care professionals. J Ren Nutr. 2014;24:110-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Koppe L, Mafra D, Fouque D. Probiotics and chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2015;88:958-966. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Vaziri ND, Pahl MV, Crum A, Norris K. Effect of uremia on structure and function of immune system. J Ren Nutr. 2012;22:149-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Claus SP, Tsang TM, Wang Y, Cloarec O, Skordi E, Martin FP, Rezzi S, Ross A, Kochhar S, Holmes E, Nicholson JK. Systemic multicompartmental effects of the gut microbiome on mouse metabolic phenotypes. Mol Syst Biol. 2008;4:219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 266] [Cited by in RCA: 273] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ramezani A, Raj DS. The gut microbiome, kidney disease, and targeted interventions. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25:657-670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 423] [Cited by in RCA: 549] [Article Influence: 42.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Vaziri ND, Wong J, Pahl M, Piceno YM, Yuan J, DeSantis TZ, Ni Z, Nguyen TH, Andersen GL. Chronic kidney disease alters intestinal microbial flora. Kidney Int. 2013;83:308-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 636] [Cited by in RCA: 858] [Article Influence: 61.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Sun G, Yin Z, Liu N, Bian X, Yu R, Su X, Zhang B, Wang Y. Gut microbial metabolite TMAO contributes to renal dysfunction in a mouse model of diet-induced obesity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;493:964-970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Missailidis C, Hällqvist J, Qureshi AR, Barany P, Heimbürger O, Lindholm B, Stenvinkel P, Bergman P. Serum Trimethylamine-N-Oxide Is Strongly Related to Renal Function and Predicts Outcome in Chronic Kidney Disease. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0141738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 273] [Article Influence: 27.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tang WH, Wang Z, Kennedy DJ, Wu Y, Buffa JA, Agatisa-Boyle B, Li XS, Levison BS, Hazen SL. Gut microbiota-dependent trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) pathway contributes to both development of renal insufficiency and mortality risk in chronic kidney disease. Circ Res. 2015;116:448-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 666] [Cited by in RCA: 978] [Article Influence: 81.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Webster AC, Nagler EV, Morton RL, Masson P. Chronic Kidney Disease. Lancet. 2017;389:1238-1252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1654] [Cited by in RCA: 2622] [Article Influence: 291.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Zeller G, Tap J, Voigt AY, Sunagawa S, Kultima JR, Costea PI, Amiot A, Böhm J, Brunetti F, Habermann N, Hercog R, Koch M, Luciani A, Mende DR, Schneider MA, Schrotz-King P, Tournigand C, Tran Van Nhieu J, Yamada T, Zimmermann J, Benes V, Kloor M, Ulrich CM, von Knebel Doeberitz M, Sobhani I, Bork P. Potential of fecal microbiota for early-stage detection of colorectal cancer. Mol Syst Biol. 2014;10:766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 651] [Cited by in RCA: 931] [Article Influence: 77.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/