Published online Dec 25, 2025. doi: 10.5527/wjn.v14.i4.111723

Revised: August 23, 2025

Accepted: October 21, 2025

Published online: December 25, 2025

Processing time: 168 Days and 21.3 Hours

Tacrolimus is a key immunosuppressive agent used to prevent allograft rejection in kidney transplant recipients. Due to its narrow therapeutic index, careful moni

A 61-year-old male with end-stage kidney disease underwent a living-unrelated donor kidney transplant at age 46 and has maintained a stable tacrolimus regimen for 15 years. He was later diagnosed with hepatocellular car

This is the first reported case of acute tacrolimus neurotoxicity and nephrotoxicity in a kidney transplant recipient following liver resection. It highlights the critical need for vigilant therapeutic drug monitoring of tacrolimus after liver surgery to prevent severe adverse effects.

Core Tip: We report the first case of tacrolimus toxicity in a kidney-transplant recipient after wedge liver resection for he

- Citation: Naiyarakseree N, Wuttiputhanun T, Townamchai N, Sutherasan M, Avihingsanon Y, Udomkarnjananun S. Tacrolimus toxicity in kidney transplant recipient after wedge liver resection: A case report and review of literature. World J Nephrol 2025; 14(4): 111723

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-6124/full/v14/i4/111723.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5527/wjn.v14.i4.111723

Tacrolimus is currently the backbone of immunosuppressive medications after solid organ transplantation because of its excellent efficacy in preventing allograft rejection and improving allograft survival[1,2]. Tacrolimus is a calcineurin inhi

Since tacrolimus in the blood is metabolized mainly in the liver via cytochrome P450 3A5 (CYP3A5) as a major meta

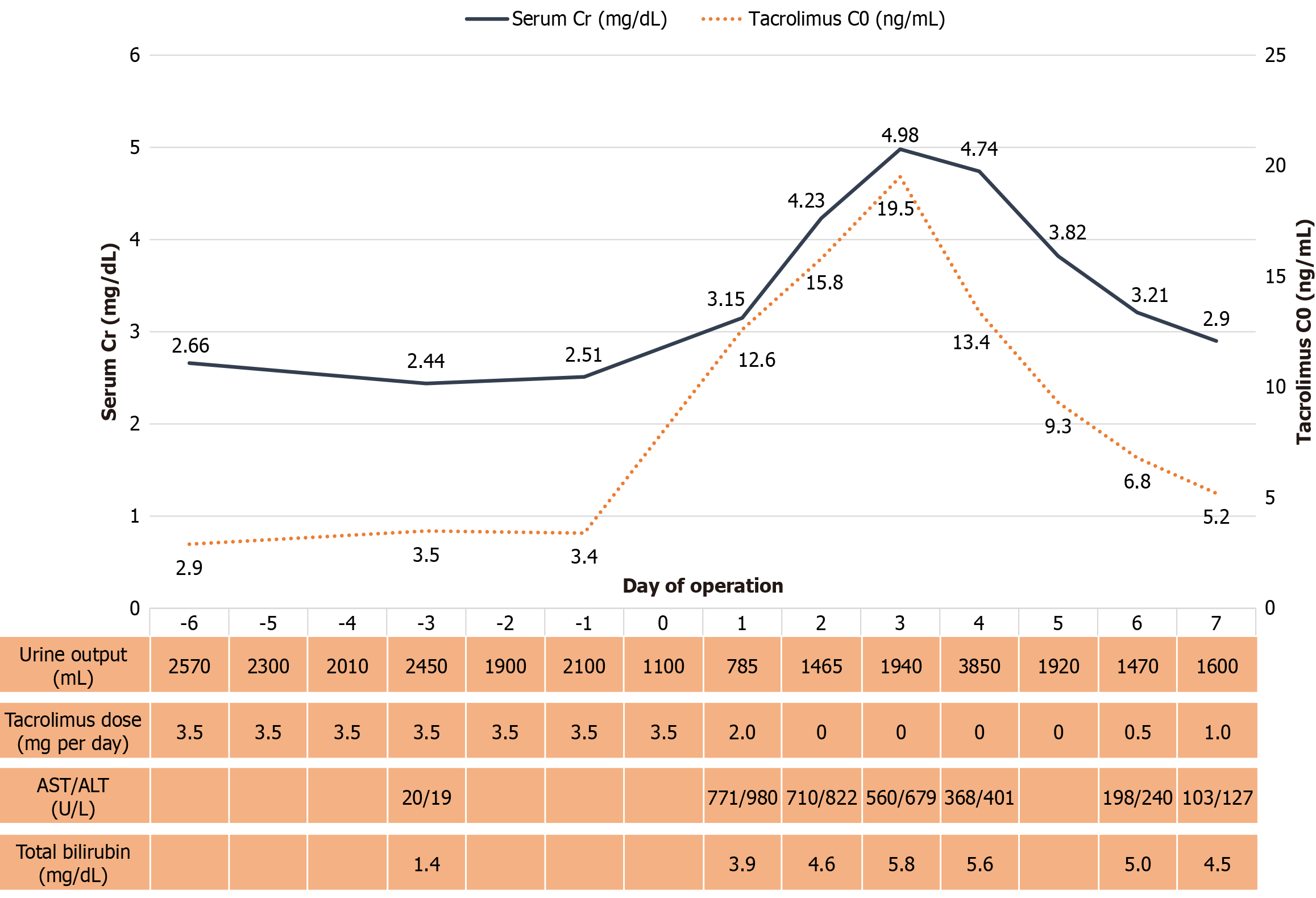

Increased serum creatinine (Cr) levels after wedge liver resection.

A 61-year-old Thailand male with end-stage kidney disease due to diabetic nephropathy underwent a living-unrelated donor kidney transplantation from his wife 15 years ago, at the age of 46. At 14 years after transplantation, abdominal ul

The human leukocyte antigen mismatches were 2-2-2 with 0% panel reactive antibodies and negative cytotoxic-depen

Seven years after transplantation, his serum Cr level increased from 1.50 mg/dL to 1.81 mg/dL with increased pro

No significant personal or family history was found.

He was afebrile; his blood pressure, heart rate, and respiratory rate were 138/86 mmHg, 80 beats/minutes, and 16 brea

On postoperative day 1, transient abnormal liver function was observed, with alanine transaminase increasing from 19 U/L to 980 U/L and aspartate aminotransferase increasing from 20 U/L to 771 U/L. Both enzymes returned to normal levels by postoperative day 10 following supportive intravenous fluid administration, with alanine transaminase at 24

The tacrolimus C0 was elevated to 12.6 ng/mL on the morning of postoperative day 1, despite no change in the tac

No imaging examinations were performed.

HCC in a kidney transplant recipient with tacrolimus toxicity after wedge liver resection and transient ischemic liver injury.

The primary management consisted of supportive care, and tacrolimus was temporarily withheld during the period of transient liver injury and ischemic hepatitis. It was reinitiated when the trough concentration returned to the target range and the liver function tests had improved.

During the period of elevated tacrolimus C0, serum Cr also increased, peaking at 4.98 mg/dL on postoperative day 3. It gradually returned to baseline by postoperative day 7, coinciding with the normalization of tacrolimus C0 and liver func

We report the case of a kidney transplant recipient with HCC who developed acute CNI toxicity following liver resection. Tacrolimus C0 was significantly elevated, accompanied by new-onset tremor, headache, and acute kidney injury (AKI). Other than tacrolimus toxicity, no other identifiable causes for the patient’s symptoms were found. After tacrolimus was withdrawn and its concentration returned to therapeutic levels, both AKI and the tremor resolved, supporting the diagnosis of tacrolimus-induced kidney injury and neurotoxicity following liver resection.

Tacrolimus is recognized as a drug with a narrow therapeutic index, where its concentrations are closely related to both its efficacy (e.g., prevention of rejection) and its potential toxicities. It is well documented that the long-term use of tacrolimus in kidney and non-kidney transplantations causes nephrotoxicity and neurotoxicity[7-9]. However, the to

Several factors have been reported in the literature that contribute to the development of AKI after liver surgery in non-transplant patients, including massive intraoperative blood loss leading to renal hypoperfusion, liver failure after hepatectomy, hepatorenal syndrome, sepsis, and nephrotoxic drugs[10,11]. However, CNI nephrotoxicity is an additional important factor in kidney transplant recipients. The differential diagnosis and approach to AKI after liver surgery are shown in Table 1[12-14].

| Conditions | Clinical clues |

| Renal hypoperfusion from intraoperative blood loss | Prolonged MAP < 65 mmHg, oliguria, history of large volume loss, improvement with fluids/transfusion |

| Abdominal compartment syndrome | Tense abdomen, rising airway pressures, refractory oliguria, large-volume resuscitation/bleeding/packing in major liver resection (IAH ≥ 12 mmHg; ACS > 20 mmHg + organ dysfunction) |

| Hepatorenal syndrome | Bland urine; no shock/nephrotoxins; no response after adequate volume resuscitation, low FENa, decompensated liver disease, usually with ascites |

| Ischemic ATI | Persistent creatinine rise with history of poor renal perfusion, granular casts, FENa > 2% (caution with diuretics), slow recovery, poor response to fluid resuscitation |

| Sepsis-associated AKI | Sepsis definition (based on Sepsis-3 criteria; infection + SOFA score) with AKI |

| Bile cast nephropathy | Marked cholestasis (total bilirubin usually > 20 mg/dL), bilirubinuria, bland or bile-pigmented casts |

| Nephrotoxic drugs (non-CNI) | Recent exposure: IV contrast, aminoglycosides, amphotericin, NSAIDs, etc. (also considered antibiotics or other drugs-associated AIN) |

| Acute CNI nephrotoxicity | Acute, dose-dependent afferent arteriolar vasoconstriction, temporal relation to high troughs, improves with dose reduction/cessation, biopsy rarely needed if rapid reversal |

Tacrolimus is metabolized by CYP3A5 isoenzymes in the liver and intestinal wall, with highly variable expression among individuals. It is primarily eliminated via the biliary route, with more than 95% of its metabolites being excreted this way[15,16]. Therefore, hepatic dysfunction is one of the most critical factors affecting tacrolimus pharmacokinetics. Poor liver function can reduce tacrolimus clearance by up to two-thirds and prolong its elimination half-life by up to threefold[15]. Our patient underwent liver surgery involving an estimated 30%-40% resection of total liver tissue, along with prolonged cold ischemia time and reperfusion injury. These factors could have significantly impaired tacrolimus clearance, leading to systemic accumulation and subsequent toxicity.

A previous study reported a 19% incidence of tacrolimus-induced neurotoxicity in the early post-liver transplant pe

Although the effect of the donor CYP3A5 genotype on liver allografts has been well documented, its impact on kidney allografts remains inconclusive. Some studies have suggested that the donor CYP3A5*3/*3 genotype (non-expressor phenotype) is associated with increased CNI nephrotoxicity due to reduced intra-allograft tacrolimus clearance. Con

Importantly, no prior reports have described CNI toxicity in a kidney transplant recipient following liver resection, as in the present case. However, tacrolimus toxicity following liver surgery has been frequently reported in liver transplant recipients[17-19,24]. Furthermore, tacrolimus toxicity has been reported in cases of cholestasis and biliary tract obstru

Several mechanisms have been proposed for tacrolimus-induced neurotoxicity, including the dysregulation of vasoconstrictive pathways and alterations in blood-brain barrier permeability[27,28]. Interestingly, among solid organ transplants, liver transplantation has the highest reported incidence of neurotoxicity, likely due to impaired tacrolimus metabolism in the early post-transplant period. Most evidence suggests a correlation between peak tacrolimus concentrations and neurotoxicity[27]. A study demonstrated that extended-release tacrolimus, which produces lower peak concentrations, was associated with a lower incidence of tremors compared with immediate-release tacrolimus[29]. However, the relationship between tacrolimus concentrations and nephrotoxicity remains less well-defined and may involve the free form of tacrolimus found in anemic patients or local tacrolimus metabolism within the kidney allograft in addition to systemic exposure[21,30]. Approximately 85% of tacrolimus partitions into erythrocytes. The erythrocyte-bound fraction decreases and the plasma free fraction increases in patients with anemia. If standard whole-blood trough targets are applied without adjustment for anemia, the higher free fraction can lead to overexposure and toxicity; therefore, reduced whole-blood targets may be appropriate in patients with anemia[3,31]. Decreased intragraft tacrolimus metabolism - observed in kidneys from CYP3A5 non-expressing donors - is associated with an increased risk of tacrolimus nephrotoxicity, likely due to impaired allograft clearance[21].

We hypothesized that the tacrolimus toxicity in our patient was driven by abnormally high peak concentrations, reflected by elevated tacrolimus C0 levels. Although other perioperative factors may have contributed to tacrolimus toxicity, the rapid postoperative increase in tacrolimus concentration, along with the onset and resolution of symptoms correlating with drug levels, strongly suggests an operative impact on tacrolimus pharmacokinetics.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of CNI-induced neurotoxicity and nephrotoxicity in a kidney transplant recipient following wedge liver resection - a scenario distinct from previously reported cases in liver transplant recipients. Because tacrolimus is primarily metabolized in the liver, a reduction in liver mass and ischemic injury to the remaining liver tissue may impair drug metabolism and clearance, leading to prolonged elevations in whole-blood tacrolimus concentrations, even after the drug is discontinued. This case highlights the need for close monitoring of tacrolimus levels following non-transplant liver surgery as part of therapeutic drug management in such patients.

| 1. | Ekberg H, Tedesco-Silva H, Demirbas A, Vítko S, Nashan B, Gürkan A, Margreiter R, Hugo C, Grinyó JM, Frei U, Vanrenterghem Y, Daloze P, Halloran PF; ELITE-Symphony Study. Reduced exposure to calcineurin inhibitors in renal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2562-2575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1362] [Cited by in RCA: 1417] [Article Influence: 74.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Udomkarnjananun S, Schagen MR, Hesselink DA. A review of landmark studies on maintenance immunosuppressive regimens in kidney transplantation. Asian Biomed (Res Rev News). 2024;18:92-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Udomkarnjananun S, Eiamsitrakoon T, de Winter BCM, van Gelder T, Hesselink DA. Should we abandon therapeutic drug monitoring of tacrolimus in whole blood and move to intracellular concentration measurements? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2025;91:1530-1541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Udomkarnjananun S, Townamchai N, Virojanawat M, Avihingsanon Y, Praditpornsilpa K. An Unusual Manifestation of Calcineurin Inhibitor-Induced Pain Syndrome in Kidney Transplantation: A Case Report and Literature Review. Am J Case Rep. 2018;19:442-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Braithwaite HE, Darley DR, Brett J, Day RO, Carland JE. Identifying the association between tacrolimus exposure and toxicity in heart and lung transplant recipients: A systematic review. Transplant Rev (Orlando). 2021;35:100610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Farouk SS, Rein JL. The Many Faces of Calcineurin Inhibitor Toxicity-What the FK? Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2020;27:56-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 28.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | van Dommelen JEM, Grootjans H, Uijtendaal EV, Ruigrok D, Luijk B, van Luin M, Bult W, de Lange DW, Kusadasi N, Droogh JM, Egberts TCG, Verschuuren EAM, Sikma MA. Tacrolimus Variability and Clinical Outcomes in the Early Post-lung Transplantation Period: Oral Versus Continuous Intravenous Administration. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2024;63:683-693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Suilik HA, Al-Shammari AS, Soliman Y, Suilik MA, Naeim KA, Nawlo A, Abuelazm M. Efficacy of tacrolimus versus cyclosporine after lung transplantation: an updated systematic review, meta-analysis, and trial sequential analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2024;80:1923-1935. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Walters S, Yerkovich S, Hopkins PM, Leisfield T, Winks L, Chambers DC, Divithotawela C. Erratic tacrolimus levels at 6 to 12 months post-lung transplant predicts poor outcomes. JHLT Open. 2024;3:100043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Peres LA, Bredt LC, Cipriani RF. Acute renal injury after partial hepatectomy. World J Hepatol. 2016;8:891-901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bredt LC, Peres LAB. Risk factors for acute kidney injury after partial hepatectomy. World J Hepatol. 2017;9:815-822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cullaro G, Kanduri SR, Velez JCQ. Acute Kidney Injury in Patients with Liver Disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022;17:1674-1684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 13. | Nadim MK, Kellum JA, Forni L, Francoz C, Asrani SK, Ostermann M, Allegretti AS, Neyra JA, Olson JC, Piano S, VanWagner LB, Verna EC, Akcan-Arikan A, Angeli P, Belcher JM, Biggins SW, Deep A, Garcia-Tsao G, Genyk YS, Gines P, Kamath PS, Kane-Gill SL, Kaushik M, Lumlertgul N, Macedo E, Maiwall R, Marciano S, Pichler RH, Ronco C, Tandon P, Velez JQ, Mehta RL, Durand F. Acute kidney injury in patients with cirrhosis: Acute Disease Quality Initiative (ADQI) and International Club of Ascites (ICA) joint multidisciplinary consensus meeting. J Hepatol. 2024;81:163-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 61.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zarbock A, Nadim MK, Pickkers P, Gomez H, Bell S, Joannidis M, Kashani K, Koyner JL, Pannu N, Meersch M, Reis T, Rimmelé T, Bagshaw SM, Bellomo R, Cantaluppi V, Deep A, De Rosa S, Perez-Fernandez X, Husain-Syed F, Kane-Gill SL, Kelly Y, Mehta RL, Murray PT, Ostermann M, Prowle J, Ricci Z, See EJ, Schneider A, Soranno DE, Tolwani A, Villa G, Ronco C, Forni LG. Sepsis-associated acute kidney injury: consensus report of the 28th Acute Disease Quality Initiative workgroup. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2023;19:401-417. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 410] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Staatz CE, Tett SE. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of tacrolimus in solid organ transplantation. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004;43:623-653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 579] [Cited by in RCA: 697] [Article Influence: 31.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Möller A, Iwasaki K, Kawamura A, Teramura Y, Shiraga T, Hata T, Schäfer A, Undre NA. The disposition of 14C-labeled tacrolimus after intravenous and oral administration in healthy human subjects. Drug Metab Dispos. 1999;27:633-636. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Alissa DA, Alkortas D, Alsebayel M, Almasuood RA, Aburas W, Altamimi T, Devol EB, Al-Jedai AH. Tacrolimus-Induced Neurotoxicity in Early Post-Liver Transplant Saudi Patients: Incidence and Risk Factors. Ann Transplant. 2022;27:e935938. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lué A, Martinez E, Navarro M, Laredo V, Lorente S, Jose Araiz J, Agustin Garcia-Gil F, Serrano MT. Donor Age Predicts Calcineurin Inhibitor Induced Neurotoxicity After Liver Transplantation. Transplantation. 2019;103:e211-e215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Balderramo D, Prieto J, Cárdenas A, Navasa M. Hepatic encephalopathy and post-transplant hyponatremia predict early calcineurin inhibitor-induced neurotoxicity after liver transplantation. Transpl Int. 2011;24:812-819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Liu J, Chen D, Yao B, Guan G, Liu C, Jin X, Wang X, Liu P, Sun Y, Zang Y. Effects of donor-recipient combinational CYP3A5 genotypes on tacrolimus dosing in Chinese DDLT adult recipients. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;80:106188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Udomkarnjananun S, Townamchai N, Chariyavilaskul P, Iampenkhae K, Pongpirul K, Sirichindakul B, Panumatrassamee K, Vanichanan J, Avihingsanon Y, Eiam-Ong S, Praditpornsilpa K. The Cytochrome P450 3A5 Non-Expressor Kidney Allograft as a Risk Factor for Calcineurin Inhibitor Nephrotoxicity. Am J Nephrol. 2018;47:182-190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Warzyszyńska K, Zawistowski M, Karpeta E, Jałbrzykowska A, Kosieradzki M. Donor CYP3A5 Expression Decreases Renal Transplantation Outcomes in White Renal Transplant Recipients. Ann Transplant. 2022;27:e936276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Joy MS, Hogan SL, Thompson BD, Finn WF, Nickeleit V. Cytochrome P450 3A5 expression in the kidneys of patients with calcineurin inhibitor nephrotoxicity. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:1963-1968. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kahveci F, Kendirli T, Gurbanov A, Botan E, Koloğlu M, Bektaş Ö, Kuloglu Z, Balcı D, Kansu A. Tacrolimus toxicity-related chorea in an infant after liver transplantation. Acute Crit Care. 2022;37:477-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Chan S, Burke MT, Johnson DW, Francis RS, Mudge DW. Tacrolimus Toxicity due to Biliary Obstruction in a Combined Kidney and Liver Transplant Recipient. Case Rep Transplant. 2017;2017:9096435. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Furukawa H, Imventarza O, Venkataramanan R, Suzuki M, Zhu Y, Warty VS, Fung J, Todo S, Starzl TE. The effect of bile duct ligation and bile diversion on FK506 pharmacokinetics in dogs. Transplantation. 1992;53:722-725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 27. | Verona P, Edwards J, Hubert K, Avorio F, Re VL, Di Stefano R, Carollo A, Johnson H, Provenzani A. Tacrolimus-Induced Neurotoxicity After Transplant: A Literature Review. Drug Saf. 2024;47:419-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Bentata Y. Tacrolimus: 20 years of use in adult kidney transplantation. What we should know about its nephrotoxicity. Artif Organs. 2020;44:140-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Langone A, Steinberg SM, Gedaly R, Chan LK, Shah T, Sethi KD, Nigro V, Morgan JC; STRATO Investigators. Switching STudy of Kidney TRansplant PAtients with Tremor to LCP-TacrO (STRATO): an open-label, multicenter, prospective phase 3b study. Clin Transplant. 2015;29:796-805. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 30. | Chienwichai K, Phirom S, Wuttiputhanun T, Leelahavanichkul A, Townamchai N, Avihingsanon Y, Udomkarnjananun S. A systematic review and meta-analysis of factors contributing to post-kidney transplant anemia and the effect of erythropoietin-stimulating agents. Syst Rev. 2024;13:278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Piletta-Zanin A, De Mul A, Rock N, Lescuyer P, Samer CF, Rodieux F. Case Report: Low Hematocrit Leading to Tacrolimus Toxicity. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:717148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/