Published online Dec 25, 2025. doi: 10.5527/wjn.v14.i4.110749

Revised: June 30, 2025

Accepted: October 15, 2025

Published online: December 25, 2025

Processing time: 192 Days and 23.9 Hours

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are the most common bacterial infections. Esche

Core Tip: Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are prevalent and often require timely diagnosis to prevent complications. The emerging urinary biomarkers, including neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin, kidney injury molecule-1, interleukin (IL)-6, IL-8, heparin-binding protein, procalcitonin, lipopolysaccharide-binding protein, xanthine oxidase, cell-free DNA, and transrenal DNA, have shown potential in identifying infection severity, organ dysfunction, and antibiotic resistance. The review further examines how integrating these biomarkers with advanced biosensor-based diagnostic tools can enhance diagnostic sensitivity, facilitate point-of-care testing, and improve clinical outcomes. The review also underscores the im

- Citation: Pandey S, Aravaanan ASK, Bhaskar E, Silambanan S. Biomarkers innovation in urinary tract infections: Insights into pathophysiology, antibiotic resistance, and clinical applications. World J Nephrol 2025; 14(4): 110749

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-6124/full/v14/i4/110749.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5527/wjn.v14.i4.110749

The urinary system is an excretory system made up of the kidneys, ureters, urinary bladder, and urethra. Its main functions are to filter blood to remove waste and to regulate water and electrolyte balance. Infections of the urinary tract can affect any part of the urinary system. Most urinary tract infections (UTIs) involve the lower urinary tract, which includes the bladder and urethra. However, the infection can ascend to affect the kidneys also[1]. Each year, approximately 150 million people are affected by these infections, resulting in significant health issues and economic costs[2]. In 2019, India had the highest number of UTI-related deaths with 55558 fatalities[3]. UTIs can impact individuals of any age, but are common in pediatric and elderly populations. Among adults, females are the most affected due to differences in the anatomical structure and the proximity of the urethra to the anus. In clinical practice, nearly 25% of infections in women are UTIs. Between 50% and 60% of women will experience at least one episode of UTI during their lifetime. About 80% of recurrent UTIs are reinfections, with recurrences often occurring within three months of the initial infection[4]. Predisposing factors of recurrent UTIs may be structural abnormalities, poor personal hygiene, or the presence of disorders such as diabetes mellitus or an impaired immune system.

Generally, the microbiota present in the urinary tract system tend to cause impacts on other systems, such as the gas

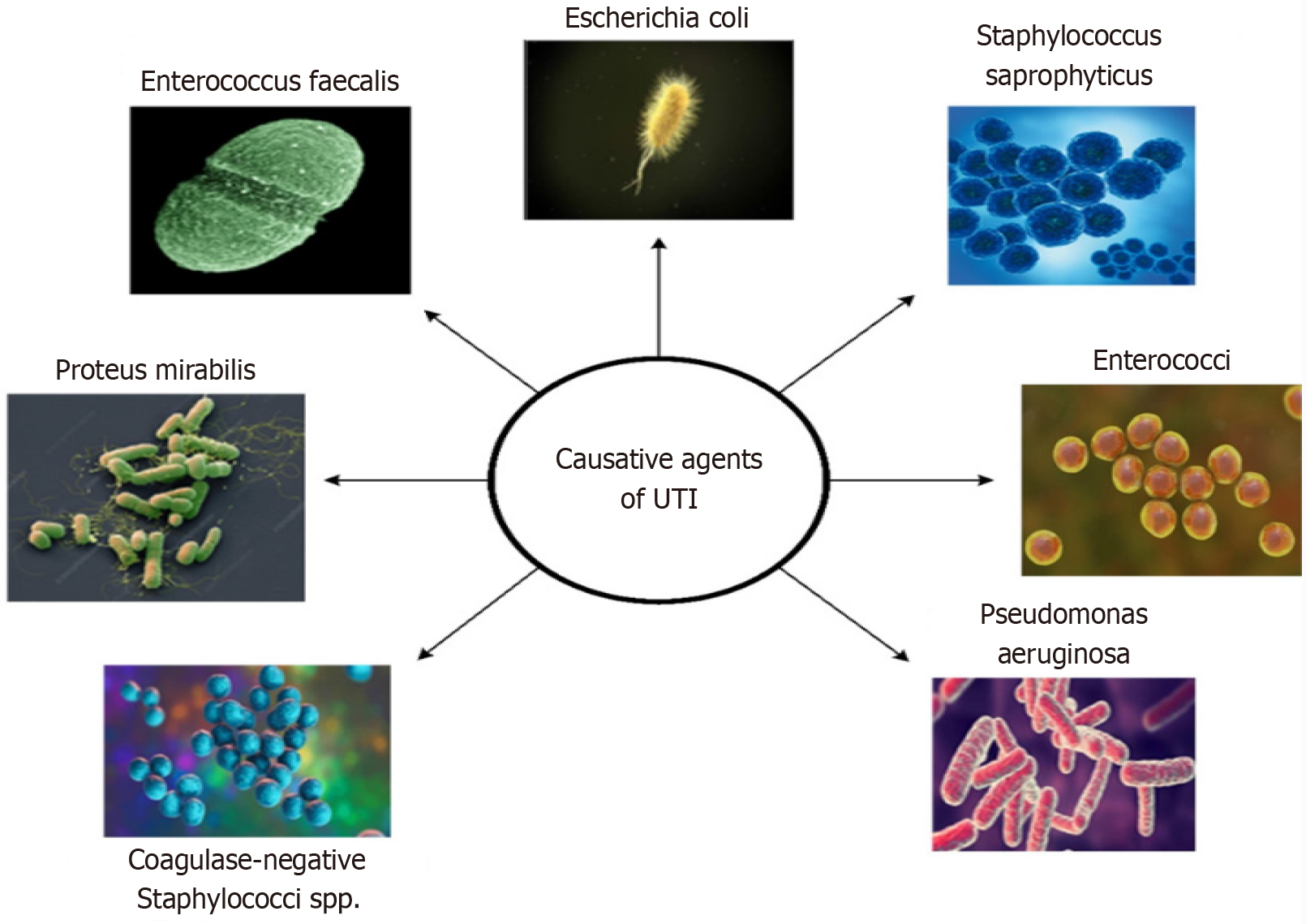

Escherichia coli is a common facultative anaerobe responsible for 85% of UTIs diagnosed at primary health facilities and approximately 50% of hospital-acquired cases[6]. Other uropathogens include Proteus mirabilis, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Enterococcus faecalis. Various virulence factors in these uropathogens enable them to adhere to the mucosal surfaces of the urinary tract, leading to infection[6]. Candida species are the most common cause of fungal UTIs, particularly among hospitalized patients, accounting for approximately 10% to 15% of all UTIs. This illness is common in diabetic patients with uncontrolled hyperglycemia and those having indwelling urinary catheters[7]. Some of the common microorganisms associated with UTIs are displayed in Figure 1 and Table 1[8,9].

| Bacteria | Factors of UTI |

| Escherichia coli | The most common cause of UTI; the pathogen ascends from the urethra to the bladder or descends from the kidneys to lower urinary tract |

| Staphylococcus saprophyticus | Present as skin flora; cause UTIs, especially in young women |

| Enterococcus faecalis | It is an opportunistic pathogen; associated with complicated UTIs, especially in hospitalized patients |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Cause antibiotic resistance; form biofilms, infect patients with catheters or those who are immunocompromised |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Affect individuals with underlying health conditions that are resistant to multiple antibiotics |

| Proteus mirabilis | Associated with catheter use and urinary retention; produces urease, which contributes to struvite stones |

| Enterobacter spp. | Cause UTIs in hospitalized patients; resistant to multiple antibiotics |

| Coagulase-negative Staphylococci spp. | Present in skin flora; cause UTIs in immunocompromised individuals or those with catheters |

To date, the diagnosis of UTI involves both clinical features and identifying the causative organism through a urine culture[10]. Clinical features of UTI include dysuria, frequent micturition, nocturia, urgency, cloudy urine, hematuria, pyuria, low back pain, high temperature, etc. The symptom-based approach is appropriate in most situations, except in specific patient groups, such as small children, the elderly, long-term catheter users, and individuals with urologic diseases. This group of patients tends to present with nonspecific clinical features[11].

White blood cells, nitrites, leukocyte esterase, or other substances present in urine also indicate the presence of infection. Timely antibiotic administration may prevent complications and facilitate a quicker recovery. Analyzing va

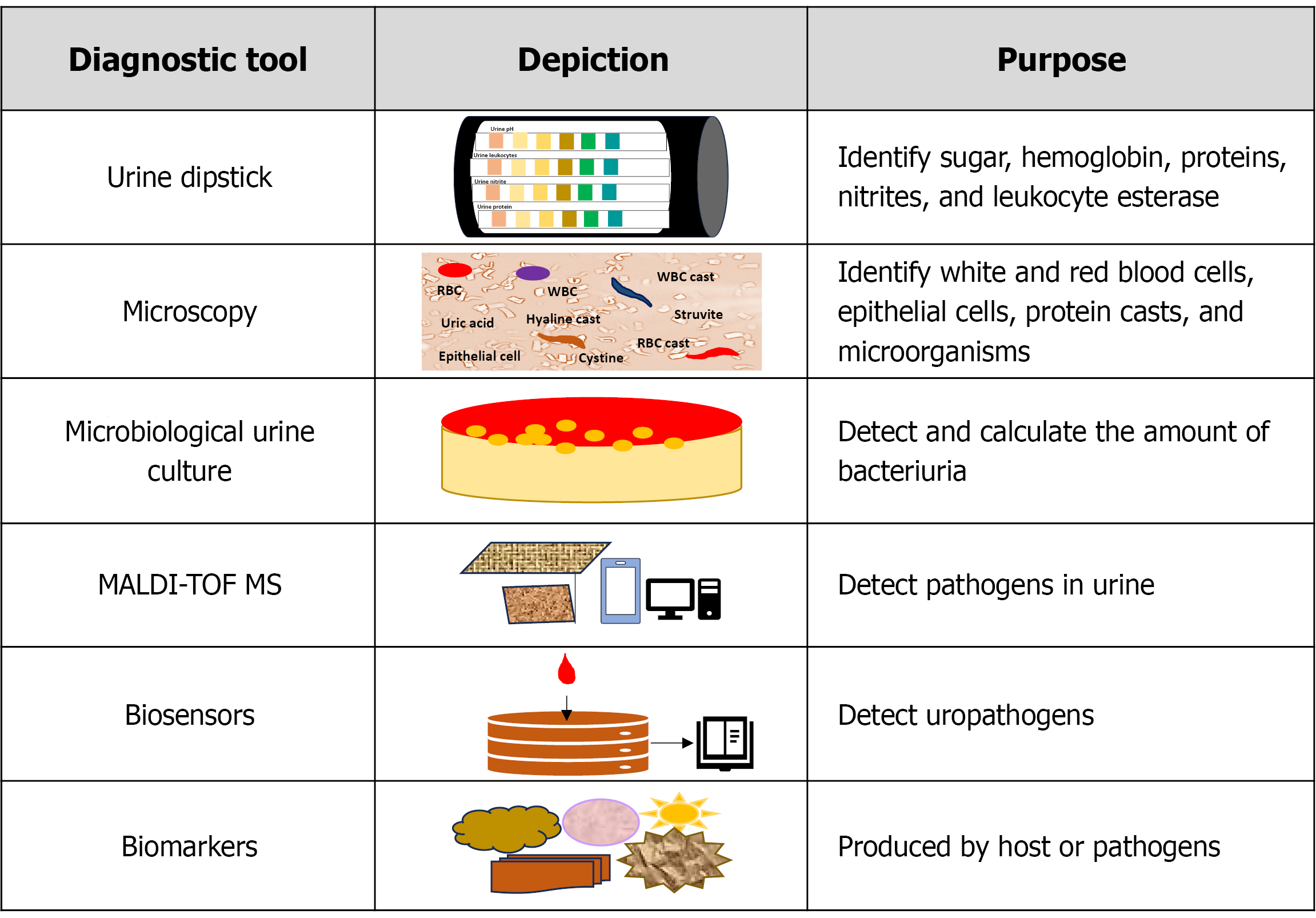

The dipstick test is a widely used point-of-care test for detecting substances in urine such as sugar, hemoglobin, proteins, nitrites, and leukocyte esterase[13]. It is a valuable tool for screening bacteriuria, especially when both nitrites and leu

Microscopic evaluation primarily focuses on identifying white and red blood cells, epithelial cells, protein casts, and microorganisms[15]. In clinical practice, the presence of white blood cells and nitrites indicates bacteriuria, and the presence of red blood cells indicates severe inflammation[15].

The culture is considered to be the standard method for the identification of pathogens causing UTIs. The culture takes at least 48 hours to 72 hours to produce definite results[16]. Urine culture using midstream urine is used to identify the pa

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) detects UTI pathogens and provides results within 18 hours to 30 hours. In the majority of clinical settings, it is essential to identify the bacteria at the species level accurately. MALDI-TOF MS can detect the strains from blood cultures, cerebrospinal fluid, and urine in addition to strains grown on solid media. Gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, aerobes, anaerobes, mycobacteria, Nocardia, yeasts, filamentous fungus, and viruses are identified by MALDI-TOF MS[19].

Developments in nanoscience and sensing technologies have led to a significant increase in the development of bio

Cystoscopy and urinary tract imaging are rarely beneficial, hence not advised for simple UTIs. But in situations where in

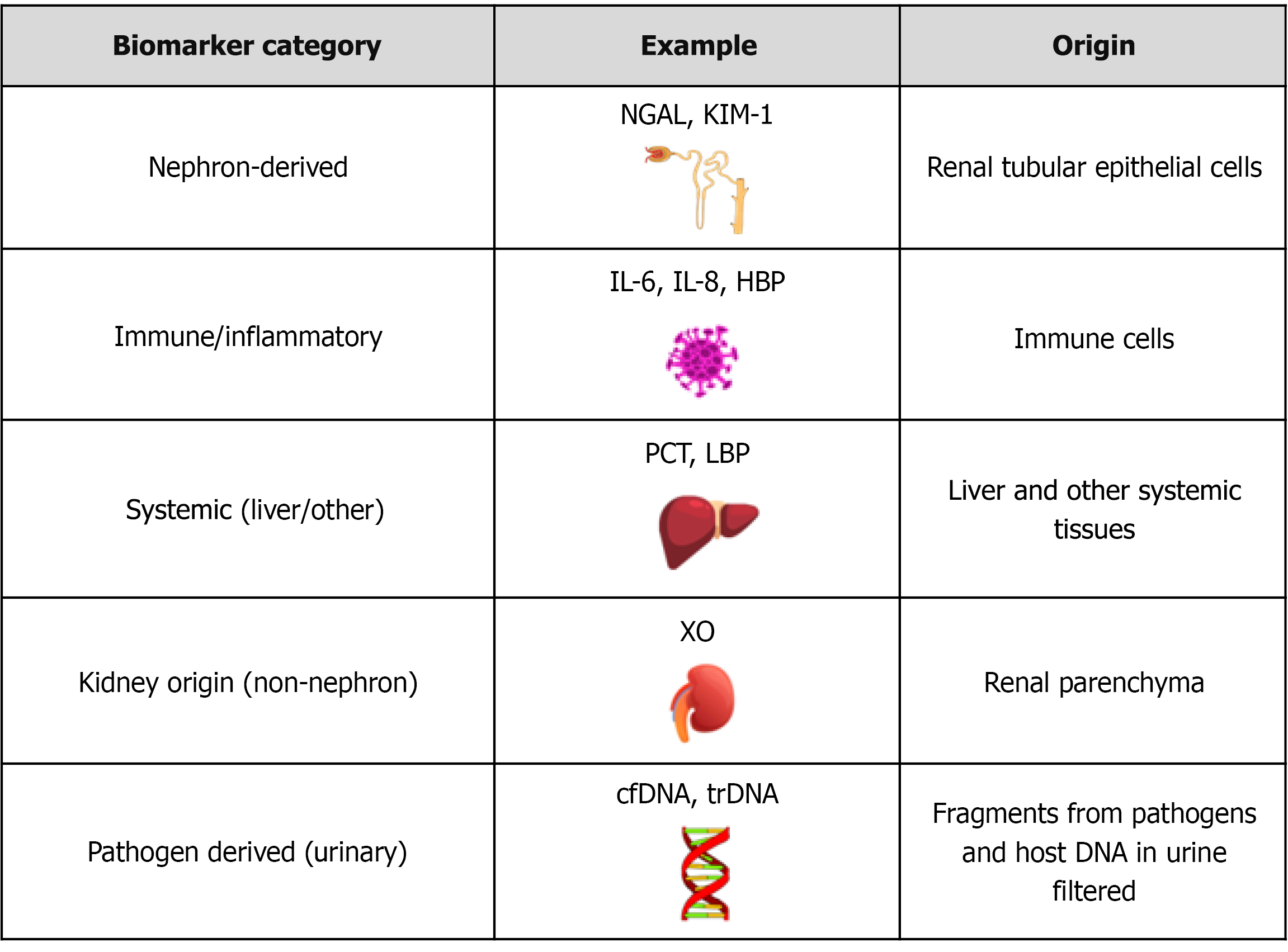

Technological advancements have enhanced the detection of UTIs and related renal involvement, particularly upper UTIs. During UTI, biomarkers are produced either by the host, as part of the immune or inflammatory response, or by the pathogenic bacteria themselves. These biomarkers become elevated in biological fluids, such as urine, blood, and other fluids. They help the clinicians in early diagnosis, assess infection severity, and monitor treatment response[21,22]. As illustrated in Figure 3, urinary biomarkers can be classified based on biological origin[21,22].

Nephron-derived biomarkers: In the presence of upper UTIs such as pyelonephritis, tubular epithelial cells may become injured and release proteins, including kidney injury molecule-1 (KIM-1) and neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), into the urine. These molecules serve as indicators of tubular damage and are valuable in distinguishing be

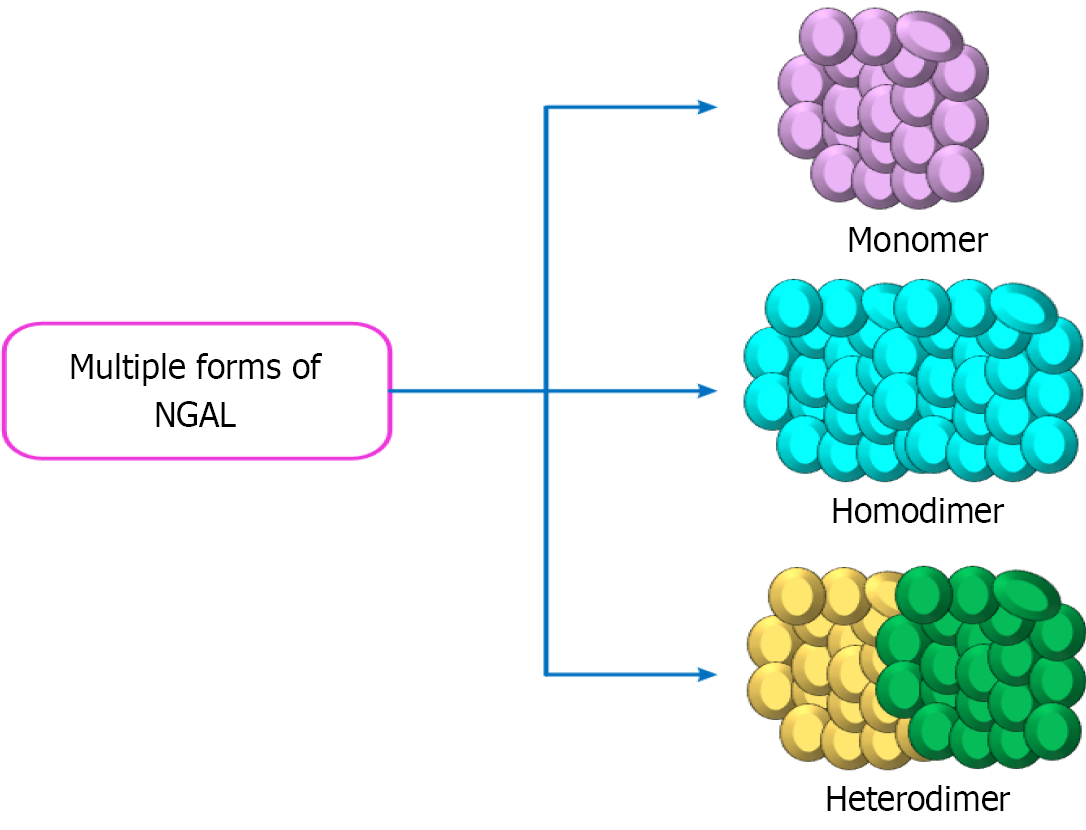

NGAL: NGAL, an acute-phase protein, was initially identified in acute kidney injury cases, especially those affecting the proximal renal tubules[21]. NGAL production also occurs within the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle and the intercalated cells of the collecting duct[21]. NGAL exists in multiple forms, including monomeric, homodimeric, and heterodimeric complexes with gelatinase, as displayed in Figure 4[23]. The monomeric form, produced by injured renal epithelial cells, is the most clinically relevant form. NGAL is also abundantly expressed by activated neutrophils during infection and inflammation[23].

NGAL is generally responsible for iron trafficking throughout the genitourinary tract, as well as for epithelial cell proliferation, differentiation, and the response to infection. Iron availability directly influences bacterial growth[24]. Most gram-negative bacteria, which require iron to survive, produce enterochelin to scavenge free iron and transport it into their cells[25]. NGAL binds to the enterochelin-iron complex, promoting its excretion through urine and exerting a ba

Infected patients exhibit elevated plasma levels of NGAL, which enhances proteolytic activity, particularly of ge

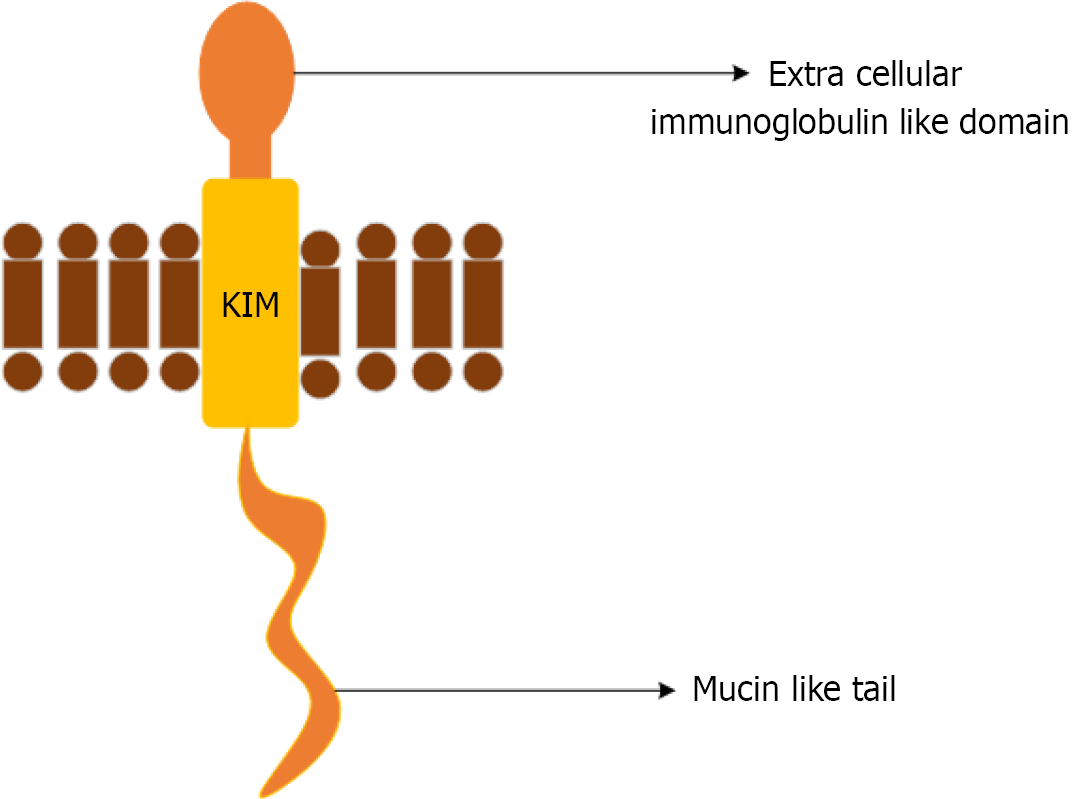

KIM-1: KIM-1 is a multifunctional protein that is rarely found in normal kidney tissues, but is expressed in proximal renal tubular epithelial cells that recover following injury. It is a transmembrane glycoprotein with an extracellular do

Clinically, KIM-1 is used to detect acute kidney injury, monitor renal function, and assess the risk of progression of kidney disease[32]. KIM-1 is highly expressed following acute ischemic, hypoxic, and toxic injuries, as well as in certain renal tubular interstitial and polycystic kidney diseases[29]. Urinary KIM-1 correlates with the severity and duration of UTIs, particularly in cases involving multidrug-resistant (MDR) uropathogens. KIM-1 levels rise dramatically within hours of UTIs, and they are associated with the severity of kidney injury[29]. But, KIM-1 lacks specificity, elevated levels are observed in non-infectious states, including renal cell carcinoma, chronic kidney disease, and other forms of toxic or ischemic injuries of kidneys[33]. Gender-related differences have also been observed in KIM-1 expression. Pediatric populations have reported higher urinary KIM-1 levels especially in females than in males, and these levels increase with age during adolescence[34].

Immune/inflammatory biomarkers: These biomarkers are produced by activated immune cells during infection or inflammation, thus reflecting the inflammatory response of the host to bacterial invasion[35]. Upon detecting pathogen invasion, urinary tract epithelial cells quickly mobilize resident tissue cells or circulating immune cells to the infection site to clear the bacteria. The primary innate immune cells that combat UTIs, in the early stages, are neutrophils. In infected tissue, toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) on bladder epithelial cells initiates intracellular signaling, leading to the release of inflammatory mediators and cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-6, and IL-8, which are correlated with the removal of infectious agents. Following infection, the adhesion molecules, P-selectin and E-selectin, are rapidly upregulated to facilitate neutrophil recruitment[36]: (1) IL-6: As a multifunctional cytokine, it controls several processes, including inflammation, organ development, and the acute phase response. T-helper cells, neutrophils, macrophages, hepatocytes, and podocytes express the IL-6 receptor, to which IL-6 directly binds. Additionally, a soluble IL-6 receptor exists, which enables IL-6 to influence a wide range of target cells. Macrophages respond to TNF-α, IL-1, and IL-2 by producing the chemokine, Il-8. In the nephron, IL-6 is primarily expressed by proximal tubular epithelial cells in response to inflammatory stimuli[37]. In older persons, urine IL-6 levels differentiate individuals with ABU from symptomatic UTI[38]; (2) IL-8: IL-8 functions primarily as a chemoattractant for neutrophils, facilitating their migration to sites of infection within the urinary tract. Its expression is typically localized and correlates with inflammation of the lower urinary tract[39]. Urinary levels of IL-6 and IL-8 are significantly higher in children with febrile UTIs compared to those with other febrile illnesses[40]. The urine of healthy individuals contains negligible levels of both IL-6 and IL-8. Urinary IL-6 and IL-8 levels may be helpful in the acute phase of UTI, but are not able to differentiate upper from lower UTI[39]. Systemic inflammation can cause serum IL-8 levels to increase, even when the urinary tract is not involved. Hence, using IL-8 alone may not be sufficient. When used in conjunction with clinical symptoms or in combination with NGAL or KIM-1, the likelihood of obtaining an accurate diagnosis is high[39]; and (3) Heparin-binding protein: The 37 kDa heparin-binding protein (HBP) is found in the azurophilic and secretory granules of human neutrophils. HBP works as a chemoattractant and monocyte activator while also causing vascular leakage. HBP possesses a wide range of antibacterial activity and might aid in the direct opsonization of bacteria. In children with UTIs, HBP shows elevated levels in urine. Urine HBP may distinguish pyelonephritis from cystitis. HBP is a potential UTI biomarker in ABU, as well as in those who have urogenital pathology[41,42]. Urine HBP have proven to have a higher diagnostic value than WBC, IL-6, and nitrite in children to differentiate bacterial from non-bacterial UTI. In contrast to IL-6, it exhibits a modest discriminating value between elderly patients with UTI and those who have ABU[43].

Systemic biomarkers: Acute pyelonephritis and febrile UTIs trigger a systemic host response, whereas ABU usually elicits no response or only a localized one. Afebrile, symptomatic lower UTIs produce local mucosal reactions. Because C-reactive protein (CRP), urine nitrite, leukocyte esterase, pyuria, and proteinuria have limited sensitivity and specificity, UTI diagnosis may be inaccurate, leading to overtreatment or undertreatment, which in turn risks kidney damage, an

(2) LBP: LBP is an acute-phase protein that recognizes lipopolysaccharides (LPS) on the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria. By binding to LPS and presenting it to receptors such as a cluster of differentiation (CD)14 and TLR4, LBP initiates signaling pathways that activate the innate immune response against bacterial infection. In the kidney, pericytes are found in the glomeruli (where they function as mesangial cells) and around peritubular capillaries and vasa recta in both cortex and medulla[46,47]. In disease states like sepsis, elevated LBP can interact with pericytes, making them essential targets of injury and pathology[48]. LBP is primarily secreted from the liver with substantial concentrations also released from pulmonary and gut epithelial cells. LBP facilitates the transfer of multimers of LPS to its sensing receptor consisting of CD14, TLR4, and myeloid differentiation factor (MD)2, initiating the inflammatory response. It plays a role in detoxification of LPS by transferring LPS to lipoproteins. LBP is also able to bind lipopeptides originating from both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria and to mediate their pro-inflammatory effects. It is associated with bacterial translocation in the gut, potentially adding function to this molecule by sensing/scavenging bacterial material entering the body through a deranged gut wall[49]. LBP serves as an indicator of systemic inflammation caused by bacterial infection, including gut dysbiosis. When LPS is released into the bloodstream, it leads to endotoxemia[48]. Serum LBP concentration constitutes a reliable biologic marker for the diagnosis of afebrile UTI in children[49]. However, in cases of upper UTIs, such as pyelonephritis, LBP accumulates in the urine due to release and filtration in the kidneys. Elevated levels of urinary LBP can indicate the severity of the infection in the kidney tissue, but the infection does not produce LBP[50]. Since LBP levels are influenced by systemic infections, inflammatory conditions, and liver function, LBP may not be used in isolation to diagnose UTI[50].

Non-nephron kidney-origin biomarkers: These biomarkers are released from kidney cells or tissues outside the nephron structure. These markers include xanthine oxidase (XO) and myeloperoxidase (MPO): (1) XO: XO is predominantly found in the liver, kidney, and endothelium within the human body. In the kidney, it originates from the renal vasculature, including the renal arteries and veins. The breakdown of purines by XO generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) and hydrogen peroxide, contributing to oxidative stress and inflammation. This oxidative activity makes XO a promising bio

Molecular markers: Molecular markers such as cell-free DNA (cfDNA), transrenal DNA (tr-DNA), and 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) have been applied to the diagnosis of UTI[22]. In UTI, cfDNA originates from host cells in the urinary tract or blood, while trDNA is a subset of cfDNA that crosses the kidney barrier from the blood into the urine. 16S rRNA comes from bacterial DNA and is used to identify the specific types of bacteria present in the urine, aiding in the dia

The 16S rRNA gene, present only in the bacterial chromosomal genome, contains nine hypervariable regions that allow differentiation of bacterial species through evolutionary polymorphisms[61]. This approach offers higher sensitivity and specificity compared with conventional diagnostic methods. A study demonstrated that 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing can characterize the diversity of the female urinary flora and improve species-level identification of pathogenic bacteria, even in healthy women[62]. Furthermore, it has potential utility in children when urine culture results are inconclusive, as well as in identifying urinary microbiota genera associated with UTIs in vesicoureteral reflux[63,64]. However, 16S rRNA amplicon sequencing is limited by its reliance on primer-specified amplicons, which restricts detection across all taxa (Table 2).

| Biomarkers | Clinical application | Ref. |

| NGAL | Guides UTI diagnosis and therapy, reduces unnecessary antibiotic use, and serves as a marker for disease severity | [23] |

| KIM-1 | Used for diagnosis and prognosis of renal diseases | [34] |

| IL-8 | Aids in diagnosing neonatal sepsis and serves as a marker for inflammation | [41] |

| IL-6 | Evaluate impact of therapeutic agents on urinary bacteria and systemic inflammation | [41] |

| XO | Measures nitrite levels during UTI, allowing real-time monitoring of bacterial activity and treatment efficacy | [53] |

| cfDNA and Tr-DNA | Enables early identification of bacterial infections, particularly in UTIs and post-transplant monitoring | [59] |

| HBP | Functions as an auxiliary marker for detecting bacteremia and assessing severity of infection | [44] |

| PCT | Facilitates early diagnosis and differentiation of bacterial UTIs | [63] |

| LBP | Serves as a biomarker for diagnosing febrile UTIs, particularly in pediatric patients | [51] |

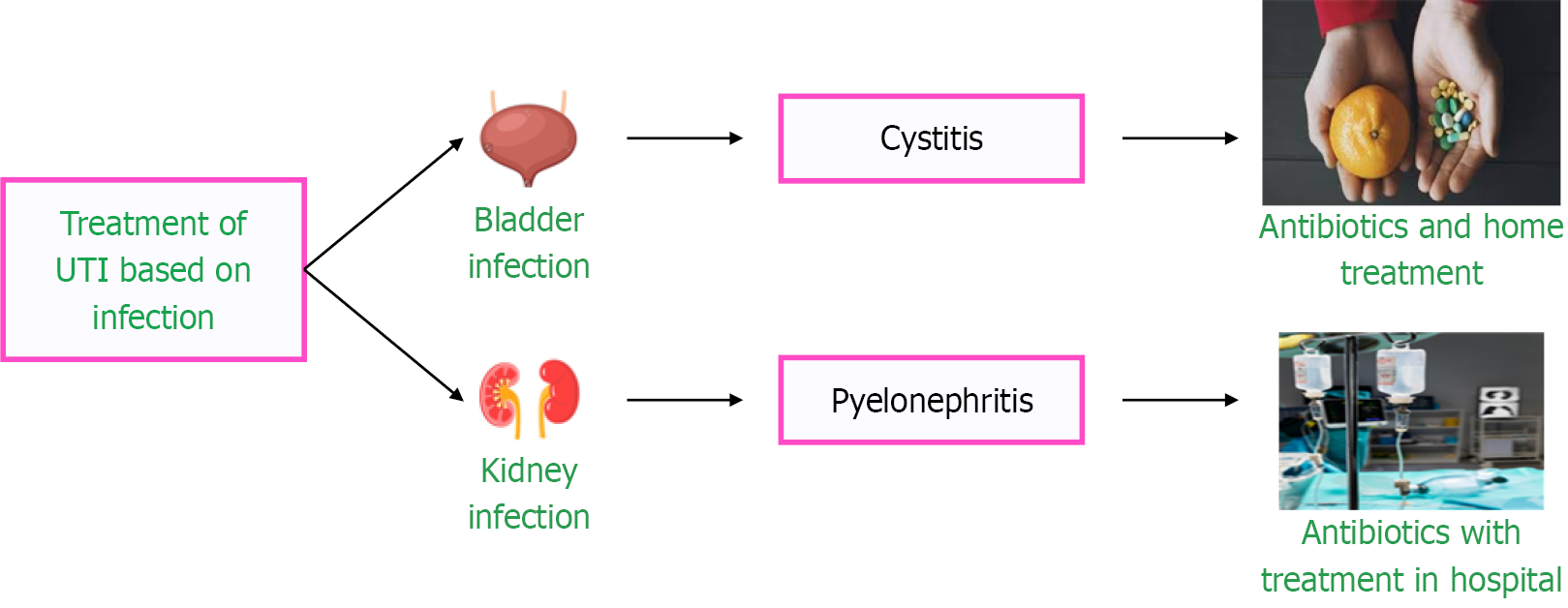

UTI treatment varies depending on the location of the infection and the causative agent, as illustrated in Figure 6. Acute uncomplicated cystitis is treated with oral antibiotics. Complicated UTIs have the risk of multi-organ dysfunction and carry high morbidity and mortality when complicated by septic shock. They are treated with injectable antibiotics, such as Ceftriaxone, Cefepime, Piperacillin-Tazobactam, and Carbapenems. A delay in appropriate antibiotic initiation can result in acute kidney injury and renal replacement therapy in severe cases[65] (Figure 6).

Globally, resistance has been developing against antibiotics used to treat bacterial infections linked to UTIs, particularly for commonly used antimicrobial medicines. Thus, it is crucial to start the appropriate empirical antibiotic treatment based on the typical etiological agents that are present in particular geographic areas. Imipenem, meropenem, amikacin, and gentamicin are the best antibiotics for treating isolates of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella spp., the most often isolated bacterial species in pediatric UTIs. Pseudomonas species exhibit resistance to imipenem, meropenem, amikacin, gen

| Bacteria | Antibiotics |

| Escherichia coli | Nitrofurantoin, Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, Fosfomycin |

| Staphylococcus saprophyticus | Nitrofurantoin, Norfloxacin Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole |

| Enterococcus faecalis | Ampicillin, Vancomycin (for resistant strains) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Ceftazidime, Piperacillin-tazobactam, Meropenem, Ciprofloxacin, Aminoglycosides |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | Ceftriaxone, Piperacillin-tazobactam, Fluoroquinolones (if susceptible), Aminoglycosides |

| Proteus mirabilis | Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, Ciprofloxacin |

| Enterobacter spp. | Cefepime (less resistant strains), Fluoroquinolones (susceptible), Aminoglycosides (serious infections) |

| Coagulase-negative Staphylococci spp. | Vancomycin (for resistant strains), Oxacillin (if susceptible) |

Diagnosing, monitoring, and predicting the progression of UTIs largely depends on the presence of biomarkers. Recent studies have highlighted the crucial role of microbiology in the early detection of infections, evaluating antibiotic resistance, and facilitating more personalized treatments[22].

Doctors conducting regular urine cultures must wait 48-72 hours before deciding on a course of treatment. NGAL, KIM-1, IL-6, and IL-8 have been identified as rapid diagnostic markers for diseases. Measuring NGAL in urine can distinguish between lower and upper UTIs with a 93% and a 90%accuracy, respectively. KIM-1 appears early in the kidneys when a patient develops an infectious UTI, particularly in cases of pyelonephritis[41].

Biomarkers help to monitor the progress when fighting MDR bacteria. High levels of IL-6 and IL-8 indicate that inflammation persists in these infections. The presence of cfDNA and trDNA in urine reflects the number of bacteria and the outcome of antibiotic administration, ensuring real-time monitoring[68].

Biomarkers such as HBP and PCT assist doctors in predicting the occurrence of urosepsis. HBP levels significantly in

Separate biosensors have been created to identify markers: NGAL, IL-6, leukocyte esterase, and nitrite. A comprehensive device that combines all four markers could enhance diagnostic efficiency and promote more precise antibiotic use in the future[70].

Biomarkers play a crucial role in diagnosing UTIs, especially in groups where common symptoms can be ambiguous, such as infants and the elderly. Urinary LBP aids in distinguishing febrile UTIs from other fever-related conditions in children. For elderly patients experiencing recurrent UTIs, biomarkers such as NGAL and KIM-1 can facilitate the early detection of kidney damage[71]. Five urine markers: IL-6, azurocidin, NGAL, TIMP-2, and CXCL-9 show good diagnostic accuracy for UTI in older women. This biomarker panel can distinguish ABU from UTI[72].

Figure 7 depicts the clinical management timeline for these biomarkers, which depends on the intensity of the patient's disease. Screening samples using these indicators enables faster decision-making, allowing for short, targeted treatment at the early onset of UTI, while severe cases require long-term intervention.

To alleviate discomfort and prevent potential UTI problems, effective time management, prompt detection, and timely treatment are considered essential. Neither existing screening procedures, urine test strip analysis, nor microscopic exa

This review highlighted the integration and characterization of UTI pathology, emphasizing the diagnostic applications of urinary biomarkers, including NGAL, KIM-1, IL-8, IL-6, XO, HBP, LBP, cfDNA, and trDNA. Advances in molecular profiling techniques for urine, combined with biosensors that target specific disease markers, have enhanced the precise detection and monitoring of UTIs. The development of molecular diagnostic biosensors for detecting antibiotic sensitivity at the point of care promises to transform clinical diagnostics by providing a fast, accurate, robust, and cost-effective platform for UTI diagnosis.

| 1. | Bono MJ, Leslie SW. Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infections. 2025 Feb 21. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2025. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Mancuso G, Midiri A, Gerace E, Marra M, Zummo S, Biondo C. Urinary Tract Infections: The Current Scenario and Future Prospects. Pathogens. 2023;12:623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sujith S, Solomon AP, Rayappan JBB. Comprehensive insights into UTIs: from pathophysiology to precision diagnosis and management. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2024;14:1402941. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Al-Badr A, Al-Shaikh G. Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections Management in Women: A review. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2013;13:359-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Jones-Freeman B, Chonwerawong M, Marcelino VR, Deshpande AV, Forster SC, Starkey MR. The microbiome and host mucosal interactions in urinary tract diseases. Mucosal Immunol. 2021;14:779-792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Flores-Mireles AL, Walker JN, Caparon M, Hultgren SJ. Urinary tract infections: epidemiology, mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13:269-284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1513] [Cited by in RCA: 2394] [Article Influence: 217.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kauffman CA, Vazquez JA, Sobel JD, Gallis HA, McKinsey DS, Karchmer AW, Sugar AM, Sharkey PK, Wise GJ, Mangi R, Mosher A, Lee JY, Dismukes WE. Prospective multicenter surveillance study of funguria in hospitalized patients. The National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Mycoses Study Group. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30:14-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 321] [Cited by in RCA: 278] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Flores C, Rohn JL. Bacterial adhesion strategies and countermeasures in urinary tract infection. Nat Microbiol. 2025;10:627-645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Foxman B. The epidemiology of urinary tract infection. Nat Rev Urol. 2010;7:653-660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 836] [Cited by in RCA: 1083] [Article Influence: 72.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lin K, Fajardo K; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults: evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:W20-W24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kurotschka PK, Gágyor I, Ebell MH. Acute Uncomplicated UTIs in Adults: Rapid Evidence Review. Am Fam Physician. 2024;109:167-174. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Al-Musawi Z, Ali Al-Obaidy Q, Husein Z. The utility of urinary dipstick in the diagnosis of urinary tract infection in children. Biomed Biotechnol Res J. 2020;4:61. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Malia L, Strumph K, Smith S, Brancato J, Johnson ST, Chicaiza H. Fast and Sensitive: Automated Point-of-Care Urine Dips. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2020;36:486-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Zamanzad B. Accuracy of dipstick urinalysis as a screening method for detection of glucose, protein, nitrites and blood. East Mediterr Health J. 2009;15:1323-1328. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Suresh J, Krishnamurthy S, Mandal J, Mondal N, Sivamurukan P. Diagnostic Accuracy of Point-of-care Nitrite and Leukocyte Esterase Dipstick Test for the Screening of Pediatric Urinary Tract Infections. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2021;32:703-710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Anger J, Lee U, Ackerman AL, Chou R, Chughtai B, Clemens JQ, Hickling D, Kapoor A, Kenton KS, Kaufman MR, Rondanina MA, Stapleton A, Stothers L, Chai TC. Recurrent Uncomplicated Urinary Tract Infections in Women: AUA/CUA/SUFU Guideline. J Urol. 2019;202:282-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 280] [Article Influence: 40.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Schmiemann G, Kniehl E, Gebhardt K, Matejczyk MM, Hummers-Pradier E. The diagnosis of urinary tract infection: a systematic review. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010;107:361-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wilson ML, Gaido L. Laboratory diagnosis of urinary tract infections in adult patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:1150-1158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 336] [Cited by in RCA: 385] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Chen XF, Hou X, Xiao M, Zhang L, Cheng JW, Zhou ML, Huang JJ, Zhang JJ, Xu YC, Hsueh PR. Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) Analysis for the Identification of Pathogenic Microorganisms: A Review. Microorganisms. 2021;9:1536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hwang C, Lee WJ, Kim SD, Park S, Kim JH. Recent Advances in Biosensor Technologies for Point-of-Care Urinalysis. Biosensors (Basel). 2022;12:1020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Horváth J, Wullt B, Naber KG, Köves B. Biomarkers in urinary tract infections - which ones are suitable for diagnostics and follow-up? GMS Infect Dis. 2020;8:Doc24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sun J, Cheng K, Xie Y. Urinary Tract Infections Detection with Molecular Biomarkers. Biomolecules. 2024;14:1540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cai L, Rubin J, Han W, Venge P, Xu S. The origin of multiple molecular forms in urine of HNL/NGAL. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:2229-2235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 191] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Forster CS, Devarajan P. Neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin: utility in urologic conditions. Pediatr Nephrol. 2017;32:377-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Klebba PE, Newton SMC, Six DA, Kumar A, Yang T, Nairn BL, Munger C, Chakravorty S. Iron Acquisition Systems of Gram-negative Bacterial Pathogens Define TonB-Dependent Pathways to Novel Antibiotics. Chem Rev. 2021;121:5193-5239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (15)] |

| 26. | Schmidt-Ott KM, Mori K, Li JY, Kalandadze A, Cohen DJ, Devarajan P, Barasch J. Dual action of neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:407-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 525] [Cited by in RCA: 578] [Article Influence: 30.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Romejko K, Markowska M, Niemczyk S. The Review of Current Knowledge on Neutrophil Gelatinase-Associated Lipocalin (NGAL). Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:10470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Urbschat A, Obermüller N, Paulus P, Reissig M, Hadji P, Hofmann R, Geiger H, Gauer S. Upper and lower urinary tract infections can be detected early but not be discriminated by urinary NGAL in adults. Int Urol Nephrol. 2014;46:2243-2249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Zhang PL, Liu ML. From acute tubular injury to tubular repair and chronic kidney diseases - KIM-1 as a promising biomarker for predicting renal tubular pathology. urr Res Physiol. 2025;8:100152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Han WK, Bailly V, Abichandani R, Thadhani R, Bonventre JV. Kidney Injury Molecule-1 (KIM-1): a novel biomarker for human renal proximal tubule injury. Kidney Int. 2002;62:237-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1240] [Cited by in RCA: 1381] [Article Influence: 57.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Li ZL, Li XY, Zhou Y, Wang B, Lv LL, Liu BC. Renal tubular epithelial cells response to injury in acute kidney injury. EBioMedicine. 2024;107:105294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Zhang Y, Chen C, Mitsnefes M, Huang B, Devarajan P. Evaluation of diagnostic accuracy of urine neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin in patients with symptoms of urinary tract infections: a meta-analysis. Front Pediatr. 2024;12:1368583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Puia D, Ivănuță M, Pricop C. Kidney Injury Molecule-1 as a Biomarker for Renal Cancer: Current Insights and Future Perspectives-A Narrative Review. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26:3431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Tomczak J, Wasilewska A, Milewski R. Urine NGAL and KIM-1 in children and adolescents with hyperuricemia. Pediatr Nephrol. 2013;28:1863-1869. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | de Nooijer AH, Pickkers P, Netea MG, Kox M. Inflammatory biomarkers to predict the prognosis of acute bacterial and viral infections. J Crit Care. 2023;78:154360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Hou Y, Lv Z, Hu Q, Zhu A, Niu H. The immune mechanisms of the urinary tract against infections. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2025;15:1540149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Su H, Lei CT, Zhang C. Interleukin-6 Signaling Pathway and Its Role in Kidney Disease: An Update. Front Immunol. 2017;8:405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 392] [Article Influence: 43.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Sundén F, Wullt B. Predictive value of urinary interleukin-6 for symptomatic urinary tract infections in a nursing home population. Int J Urol. 2016;23:168-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Al Rushood M, Al-Eisa A, Al-Attiyah R. Serum and Urine Interleukin-6 and Interleukin-8 Levels Do Not Differentiate Acute Pyelonephritis from Lower Urinary Tract Infections in Children. J Inflamm Res. 2020;13:789-797. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Hosseini M, Ahmadzadeh H, Toloui A, Ahmadzadeh K, Madani Neishaboori A, Rafiei Alavi SN, Gubari MIM, Jones ME, Ataei F, Yousefifard M, Ataei N. The value of interleukin levels in the diagnosis of febrile urinary tract infections in children and adolescents; a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pediatr Urol. 2022;18:211-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Tan D, Zhao L, Peng W, Wu FH, Zhang GB, Yang B, Huo WQ. Value of urine IL-8, NGAL and KIM-1 for the early diagnosis of acute kidney injury in patients with ureteroscopic lithotripsy related urosepsis. Chin J Traumatol. 2022;25:27-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Kjölvmark C, Påhlman LI, Åkesson P, Linder A. Heparin-binding protein: a diagnostic biomarker of urinary tract infection in adults. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2014;1:ofu004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Taha AM, Abouelmagd K, Omar MM, Najah Q, Ali M, Hasan MT, Allam SA, Arian R, Rageh OES, Abd-ElGawad M. The diagnostic utility of heparin-binding protein among patients with bacterial infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2024;24:150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Lee GH, Lee YJ, Kim YW, Park S, Park J, Park KM, Jin K, Park BS. A study of the effectiveness of using the serum procalcitonin level as a predictive test for bacteremia in acute pyelonephritis. Kosin Med J. 2018;33:337-346. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Vijayan AL, Vanimaya, Ravindran S, Saikant R, Lakshmi S, Kartik R, G M. Procalcitonin: a promising diagnostic marker for sepsis and antibiotic therapy. J Intensive Care. 2017;5:51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 248] [Cited by in RCA: 287] [Article Influence: 31.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Mazgaeen L, Gurung P. Recent Advances in Lipopolysaccharide Recognition Systems. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 259] [Article Influence: 43.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Kumpf O, Gürtler K, Sur S, Parvin M, Zerbe LK, Eckert JK, Weber ANR, Oh DY, Lundvall L, Hamann L, Schumann RR. A Genetic Variation of Lipopolysaccharide Binding Protein Affects the Inflammatory Response and Is Associated with Improved Outcome during Sepsis. Immunohorizons. 2021;5:972-982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Al-Saowdy AHQ, Abbas IS. Estimation of Lipopolysaccharide Binding Protein in Urinary Tract Infection Patients. Eur J Mod Med Pract. 2024;4:240-247. |

| 49. | Tsalkidou EA, Roilides E, Gardikis S, Trypsianis G, Kortsaris A, Chatzimichael A, Tentes I. Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein: a potential marker of febrile urinary tract infection in childhood. Pediatr Nephrol. 2013;28:1091-1097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Schwartz L, de Dios Ruiz-Rosado J, Stonebrook E, Becknell B, Spencer JD. Uropathogen and host responses in pyelonephritis. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2023;19:658-671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Ciragil P, Kurutas EB, Miraloglu M. New markers: urine xanthine oxidase and myeloperoxidase in the early detection of urinary tract infection. Dis Markers. 2014;2014:269362. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Giler S, Henig EF, Urca I, Sperling O, de Vries A. Urine xanthine oxidase activity in urinary tract infection. J Clin Pathol. 1978;31:444-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Yu H, Chen X, Guo X, Chen D, Jiang L, Qi Y, Shao J, Tao L, Hang J, Lu G, Chen Y, Li Y. The clinical value of serum xanthine oxidase levels in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Redox Biol. 2023;60:102623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Rizo-Téllez SA, Sekheri M, Filep JG. Myeloperoxidase: Regulation of Neutrophil Function and Target for Therapy. Antioxidants (Basel). 2022;11:2302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Bai M, Feng J, Liang G. Urinary myeloperoxidase to creatinine ratio as a new marker for monitoring treatment effects of urinary tract infection. Clin Chim Acta. 2018;481:9-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Hu Y, Zhao Y, Zhang Y, Chen W, Zhang H, Jin X. Cell-free DNA: a promising biomarker in infectious diseases. Trends Microbiol. 2025;33:421-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 21.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Bronkhorst AJ, Ungerer V, Holdenrieder S. The emerging role of cell-free DNA as a molecular marker for cancer management. Biomol Detect Quantif. 2019;17:100087. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 376] [Cited by in RCA: 410] [Article Influence: 58.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Burnham P, Dadhania D, Heyang M, Chen F, Westblade LF, Suthanthiran M, Lee JR, De Vlaminck I. Urinary cell-free DNA is a versatile analyte for monitoring infections of the urinary tract. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Zhao Y, Zhang W, Ma Y, Zhang X. The role of cell‐free DNA in non‐invasive diagnosis of urinary tract infection. UroPrecision. 2024;2:41-50. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 60. | Umansky SR, Tomei LD. Transrenal DNA testing: progress and perspectives. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2006;6:153-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Brubaker L, Wolfe AJ. The new world of the urinary microbiota in women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015; 213: 644-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Siddiqui H, Nederbragt AJ, Lagesen K, Jeansson SL, Jakobsen KS. Assessing diversity of the female urine microbiota by high throughput sequencing of 16S rDNA amplicons. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Marshall CW, Kurs-Lasky M, McElheny CL, Bridwell S, Liu H, Shaikh N. Performance of Conventional Urine Culture Compared to 16S rRNA Gene Amplicon Sequencing in Children with Suspected Urinary Tract Infection. Microbiol Spectr. 2021;9:e0186121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Vitko D, McQuaid JW, Gheinani AH, Hasegawa K, DiMartino S, Davis KH, Chung CY, Petrosino JF, Adam RM, Mansbach JM, Lee RS. Urinary Tract Infections in Children with Vesicoureteral Reflux Are Accompanied by Alterations in Urinary Microbiota and Metabolome Profiles. Eur Urol. 2022;81:151-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Trautner BW, Cortés-Penfield NW, Gupta K, Hirsch EB, Horstman M, Moran GJ, Colgan R, O’Horo JC, Ashraf MS, Connolly S, Drekonja DM, Grigoryan L, Huttner A, Lazenby G, Nicolle L, Schaeffer A, Yawetz S, Lavergne V. Clinical Practice Guideline by Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA): 2025 Guideline on Management and Treatment of Complicated Urinary Tract Infections. [cited 25 September 2025]. Available from: https://www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/complicated-urinary-tract-infections/. |

| 66. | Altaf U, Saleem Z, Akhtar MF, Altowayan WM, Alqasoumi AA, Alshammari MS, Haseeb A, Raees F, Imam MT, Batool N, Akhtar MM, Godman B. Using Culture Sensitivity Reports to Optimize Antimicrobial Therapy: Findings and Implications of Antimicrobial Stewardship Activity in a Hospital in Pakistan. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59: 1237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Pai A, Ram HA, Chandrashekar KS, Treasa A. Towards Effective Realization of Sustainable Development Goals With Impetus on Tackling The Menace Of Drug-Resistant Urinary Tract Infection. Rasayan J Chem. 2022;19-28. |

| 68. | Berlina AN, Zherdev AV, Dzantiev BB. Monitoring Antibiotics and Inflammatory Markers in Human Blood: Impact in Choice of Antibiotic Therapy and used Methods. Biomed Pharmacol J. 2020;13:1075-1093. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 69. | Zhang GM, Guo XX. Combining PCT with CRP is better than separate testing for patients with bacteriuria in the intensive care unit: a retrospective study. Eur J Med Res. 2024;29:441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Sequeira-Antunes B, Ferreira HA. Urinary Biomarkers and Point-of-Care Urinalysis Devices for Early Diagnosis and Management of Disease: A Review. Biomedicines. 2023;11:1051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Shaikh N, Kurs-Lasky M, Liu H, Rajakumar V, Qureini H, Conway IO, Lee MC, Lee S. Biomarkers for febrile urinary tract infection in children. Front Pediatr. 2023;11:1163546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Bilsen MP, Treep MM, Aantjes MJ, van Andel E, Stalenhoef JE, van Nieuwkoop C, Leyten EMS, Delfos NM, van Uhm JIM, Sijbom M, Akintola AA, Numans ME, Achterberg WP, Mooijaart SP, van der Beek MT, Cobbaert CM, Conroy SP, Visser LG, Lambregts MMC. Diagnostic accuracy of urine biomarkers for urinary tract infection in older women: a case-control study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2024;30:216-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/