Published online Dec 25, 2025. doi: 10.5527/wjn.v14.i4.109875

Revised: June 7, 2025

Accepted: September 19, 2025

Published online: December 25, 2025

Processing time: 208 Days and 1.6 Hours

Comorbid type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and chronic kidney disease (CKD) pose significant global health challenges, particularly in the Middle East and North Africa region. This review synthesizes current evidence and clinical guide

Core Tip: Effective management of type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease (CKD) in the Middle East and North Africa region requires culturally sensitive, evidence-based strategies. Protein intake should be tailored to 0.8–1.3 g/kg/day, emphasizing plant-based sources like legumes and soy to reduce kidney stress. Glycemic control focuses on reducing refined carbohydrates, choosing low-glycemic, high-fiber foods, and sequencing meals with carbohydrates consumed last. Heart-healthy fats such as olive oil, nuts, and fatty fish should replace saturated and trans fats to lower cardiovascular risk. Electrolyte and fluid management includes limiting sodium to less than 2 g per day, restricting potassium and phosphorus from processed sources, and adjusting fluid intake based on CKD stage. Cultural adaptations are key, allowing for traditional foods like hummus and whole grains within Mediterranean or dietary approach to stop hypertension diet patterns. During Ramadan, care plans should be personalized with attention to hydration and medication adjustments to ensure safe fasting practices.

- Citation: AlShammari A, AlSahow A. Dietary management of patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease: A comprehensive literature review. World J Nephrol 2025; 14(4): 109875

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-6124/full/v14/i4/109875.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5527/wjn.v14.i4.109875

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is the leading cause of chronic kidney disease (CKD) worldwide, and their coexistence substantially increases the risks of end-stage kidney disease and cardiovascular complications, which are the primary causes of mortality in this population[1,2]. Nutritional management plays a critical role in slowing disease progression and improving clinical outcomes[3,4]. As CKD advances, metabolic changes such as protein catabolism and nitrogen waste accumulation can alter patients' senses of taste and smell, reduce appetite, and contribute to muscle and fat wasting. Patients may also experience electrolyte and acid-base imbalances, fluid retention, and mineral and bone disorders, all requiring specialized dietary interventions[3,4].

Dietary recommendations must be tailored to specific populations. The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region faces a high burden of T2DM and obesity, with rates among the highest globally. Within MENA, the gulf cooperation council (GCC) countries-Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates-show particularly high prevalence[5,6]. This metabolic challenge is compounded by traditional dietary patterns high in refined carbohy

Available evidence was collated from international Diabetes and international CKD treatment guidelines. In addition, PubMed, Cochrane library, and Google scholar were searched on 30 November 2024 for full articles in English language with the search terms “(diabetes) AND (CKD) AND (nutrition) AND (Bahrain OR Kuwait OR Oman OR Qatar OR Saudi Arabia OR KSA OR UAE OR Emirates)” without a time range, to find articles on the prevalence and management of diabetes and of CKD in the GCC countries. Similar search was done for (CKD) AND (Ramadan). We excluded abstracts, non-English language articles, and papers focused on pediatric population.

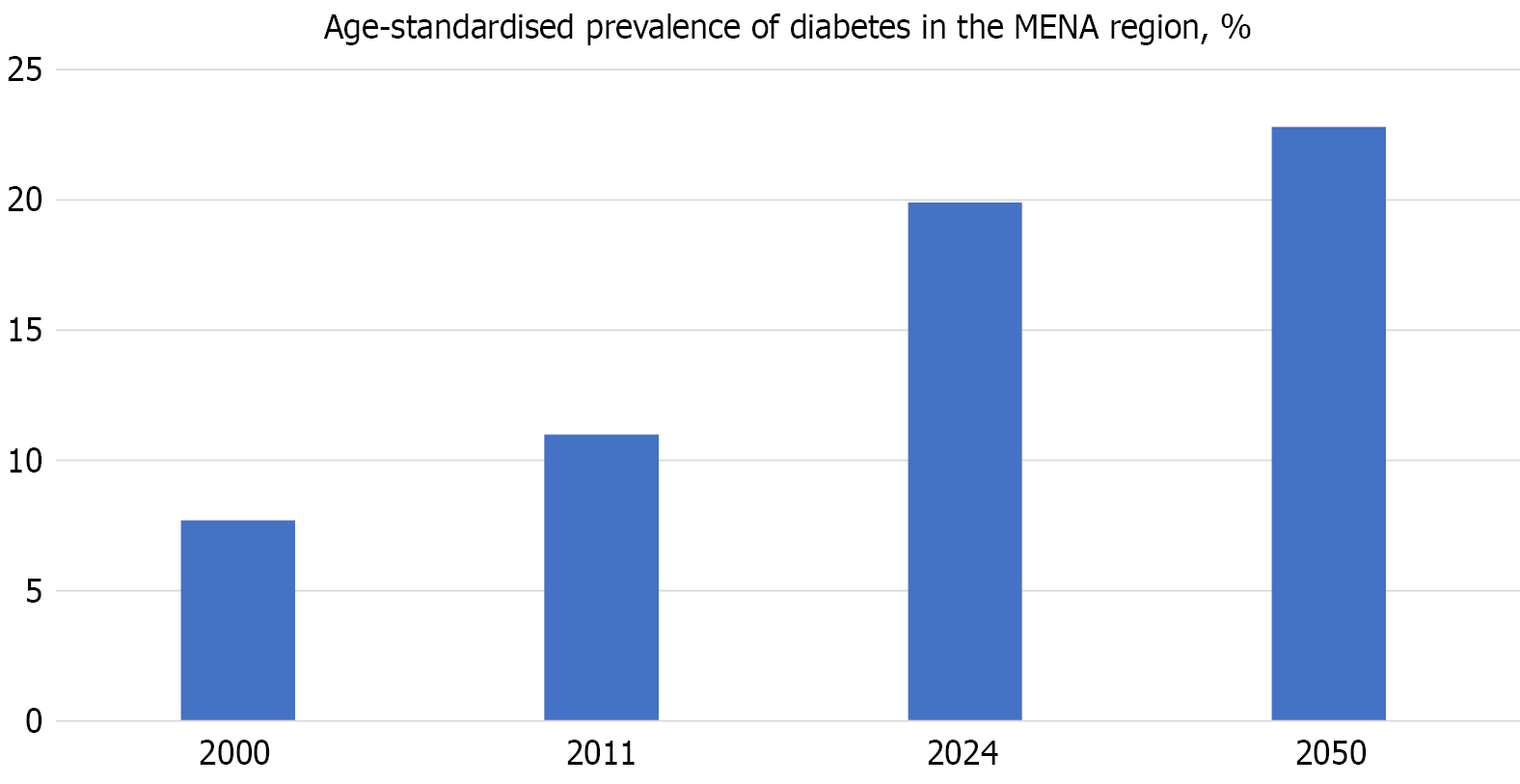

The MENA region has one of the highest global age-adjusted prevalence rates of T2DM, with approximately 73 million adults (almost 20% of adults) affected in 2021 and projections estimating an increase to 136 million by 2045[7]. This alarming increase, illustrated in Figure 1, highlights a growing public health challenge. In the Arabian Gulf, particularly within the GCC countries, the burden is especially severe. Moreover, T2DM is a leading cause of CKD, and over one-third of individuals with diabetes in the region develop CKD. The prevalence of CKD in patients with T2DM ranges from 20.6% in Saudi Arabia to 50.5% in Oman[1,8].

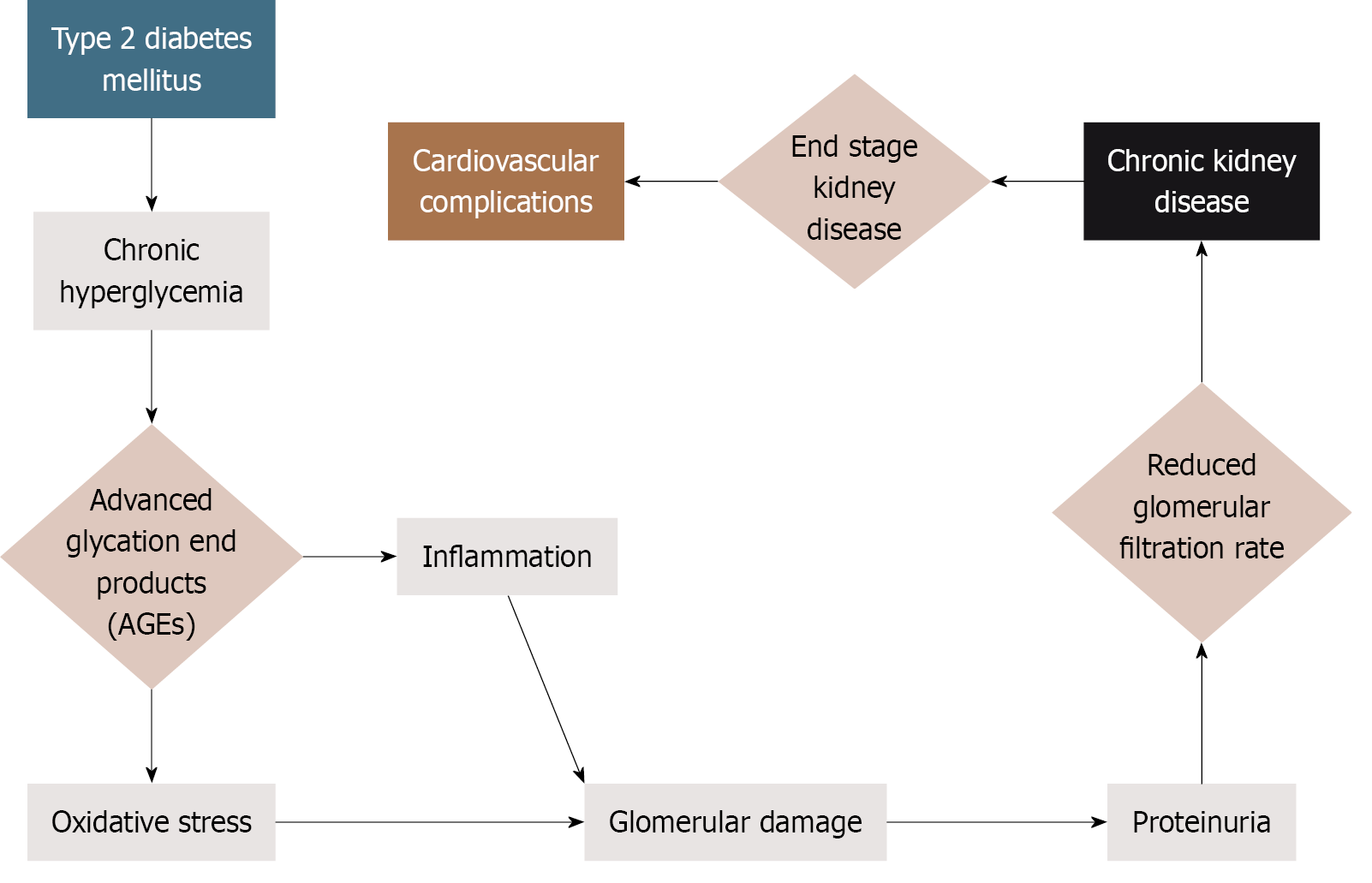

The coexistence of T2DM and CKD significantly accelerates disease progression[1,9]. Prolonged hyperglycemia and hypertension, which is characteristic of poorly controlled diabetes, trigger glomerular hyperfiltration, oxidative stress, and microvascular damage, all of which contribute to progressive renal decline[10,11]. Reduced kidney function impairs insulin clearance and glucose metabolism, establishing a self-perpetuating cycle that exacerbates clinical outcomes. Figure 2 illustrates this interconnected progression from T2DM to CKD and ultimately to cardiovascular disease, highlighting the importance of timely, regionally adapted nutritional interventions. In the GCC countries, this burden is further intensified by sedentary lifestyles, genetic predispositions (especially with high rates of consanguinity), and diets high in refined carbohydrates and sodium[12-14]. These factors demand culturally appropriate dietary strategies to slow disease progression and reduce cardiovascular risk in individuals with T2DM.

Protein intake: Dietary protein needs for patients with comorbid T2DM and CKD are generally similar to those of the general population. On average adults in the United States consume 1.34 g/kg of ideal body weight per day, exceeding the amount required to maintain nitrogen balance (0.8 g/kg of actual body weight per day)[15]. Intake varies by age, sex, and ethnicity. Individuals with T2DM frequently adopt high-protein diets to support weight loss and glycemic control[14,16]. However, high protein intake can increase the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and glomerular pressure as the kidneys work to clear nitrogen waste. This potentially accelerates renal decline[17,18]. While current guidelines, shown in Tables 1 and 2 do not recommend protein restriction for patients with T2DM only, avoiding excess intake may prevent renal complications and promote long-term kidney health[18].

| Nutrient | Key recommendations | Evidence and considerations |

| Protein | General DKD: About 0.8 g/kg/day (non-dialysis); dialysis: 1.0–1.2 g/kg/day; prioritize plant-based proteins (e.g., soy) | High protein intake may increase GFR and renal strain; plant proteins may reduce proteinuria and mortality risk vs red meat |

| Carbohydrates | Individualized intake; minimize refined sugars; consider “carbohydrate-last” eating pattern | CL eating may reduce postprandial spikes; cultural adaptations (e.g., Mediterranean diet) can improve glycemic control |

| Fats | Limit saturated fats (< 7%) and trans fats (< 1%); replace with omega-3 fatty acids (fish, flaxseeds) and monounsaturated fats (olive oil, nuts) | Mediterranean/DASH diets could lower CVD risk and improve lipids; cultural models (e.g., Levantine diet) enhance adherence |

| Nutrient | Key recommendations | Evidence and considerations |

| Potassium | Individualized restriction; prioritize natural sources (fruits/vegetables) over additives; limit processed foods with KCl | T2DM + CKD increases hyperkalemia risk (RAAS inhibitors, age); stepwise approach: Address non-dietary causes first, then limit low-nutrient sources (e.g., juices, chips); potassium additives in low sodium foods are highly bioavailable (↑ risk) |

| Phosphorus | Non-dialysis CKD: About 700 mg/day; hemodialysis: Monitor protein-bound phosphorus (1.2–1.4 g/kg/day ≈ 1450–1600 mg phosphorus) | Hyperphosphatemia drives vascular calcification; animal proteins and additives are major sources; however, strict restrictions risk malnutrition; education improves adherence in hemodialysis (limited evidence in other CKD stages) |

| Sodium | < 2 g/day (5 g salt); combine with DASH diet for BP control | High intake worsens HTN, CVD, and proteinuria; enhances RAAS-blocker efficacy but may transiently ↓eGFR (protective hyperfiltration reduction?); DASH diet + low sodium may slow CKD progression |

Protein recommendations in diabetic kidney disease (DKD) depend on the CKD stage and dialysis status. For patients not receiving dialysis, a target intake of approximately 0.8 g/kg/day is recommended to minimize uremic symptoms and slow the progression of kidney disease[19]. Patients receiving hemodialysis require 1.0-1.2 g/kg/day to compensate for treatment-related protein losses and maintain nutritional status[19]. Patients receiving peritoneal dialysis typically need 1.2-1.3 g/kg/day due to continuous protein loss through the dialysate[19]. Low-protein diets are defined as protein intake of 0.6–0.8 g/kg/day and may reduce proteinuria, oxidative stress, and metabolic burden, potentially slowing CKD progression[20]. Meta-analyses suggest modest improvements in estimated GFR (eGFR) with consistent adherence to low-protein diets; however, findings are mixed, and some studies have found no significant benefit or even potential harm[18-21]. Excessive restriction may lead to protein-energy wasting and malnutrition, particularly in older adults or those with poor nutritional status[21]. However, with adequate caloric intake and, when appropriate, keto acid supplementation, low-protein diets have been shown to preserve muscle mass, improve metabolic control, and avoid malnutrition. Thus, protein restriction should be individualized and monitored closely by a renal dietitian.

The source and quality of dietary protein critically influence DKD outcomes. While red meat intake is associated with increased risk of end-stage kidney disease[22,23], replacing it with plant-based proteins (particularly soy) can reduce proteinuria and improves metabolic markers[21]. Plant proteins are generally safe and may be renoprotective in CKD stages 1-3a, though stages 3b-5 require monitoring of potassium/phosphorus; techniques like soaking legumes and peeling vegetables can mitigate risks[12]. Although plant-based diets raise concerns about potassium/phosphate content, these nutrients are less bioavailable than in animal sources, and the higher fiber/alkaline content benefits CKD patients[12]. Higher plant protein intake is linked to lower all-cause mortality in CKD[24], supporting recommendations that > 50% of protein be plant-sourced, individualized by CKD stage, nutritional status, and cultural preferences[21-23].

Glycemic management and carbohydrate intake: Effective glycemic control is essential in managing T2DM and slowing DKD progression. While glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) remains the standard marker of long-term glycemia, its accuracy diminishes in the presence of advanced CKD due to anemia, reduced RBC lifespan, and iron deficiency[25]. Continuous glucose monitoring provides a more accurate assessment, particularly in later CKD stages[26,27]. Current guidelines recommend individualized HbA1c targets ranging from < 6.5%-8.0%, based on CKD stage, comorbidities, and hypogly

Medical nutrition therapy (MNT) is central to non-pharmacological glycemic management. Carbohydrate intake should be consistent across meals and individualized, with a focus on minimizing added sugars and refined carbohy

Implementing these recommendations requires cultural adaptation to address traditional Middle Eastern dietary patterns and religious practices. Traditional diets in the region are often high in refined grains (e.g., white rice), dates, and sugar-rich desserts like basbousa and baklava, posing challenges for patients with T2DM and CKD[30]. Glycemic management strategies must account for cultural factors including Ramadan fasting and communal eating traditions, necessitating collaboration between patients and dietitians to develop sustainable approaches[12]. Evidence-based diets like the Mediterranean diet can be adapted to local preferences by emphasizing whole grains, legumes, and unsweetened plant-based foods while respecting cultural food practices, which may improve glycemic control and renal outcomes in DKD[33].

Lifestyle modification remains central to glycemic control. Intensive glycemic management in early-stage CKD has been shown to reduce microvascular complications. The benefits of lifestyle modifications do become less pronounced in advanced disease. At this point the risks of hypoglycemia increase due to impaired renal insulin clearance, reduced gluconeogenesis, poor nutritional intake, and glucose losses during hemodialysis[29]. Nonetheless, studies suggest that a legacy effect where early intervention yields long-term benefits is present[34]. Furthermore, very low-calorie diets can normalize blood glucose and improve both insulin sensitivity and beta cell function, particularly in individuals who have had a shorter T2DM duration[35,36]. A comprehensive approach that integrates individualized dietary therapy, culturally appropriate counselling, physical activity, and pharmacological strategies offers the best opportunity to optimize glycemic control and slow the progression of DKD.

Fat intake: Patients with CKD face an elevated risk of cardiovascular complications. Indeed, heart-related conditions are the primary cause of mortality in this population[37,38]. To manage this risk patients with CKD are advised to follow the National Cholesterol Education Program (ATP III) guidelines, which recommend a total fat intake of 25%-35% of daily calories with saturated fat limited to less than 7% and trans fats to less than 1%[39]. Saturated fats are commonly found in fatty cuts of red meat, full-fat dairy products, butter, and palm oil, while trans fats are present in hydrogenated oils, processed baked goods, fried foods, and some margarine[40]. Reducing these harmful fats is essential, and replacing them with healthier fats can improve lipid profiles and reduce inflammation[41]. Polyunsaturated fats, especially omega-3 fatty acids from fatty fish such as salmon, mackerel, and sardines as well as from flaxseeds, chia seeds, and walnuts, have been shown to reduce inflammation and improve blood lipid levels[42]. Monounsaturated fats from sources such as olive oil, canola oil, avocados, and nuts are also associated with improved lipid profiles and reduced cardiovascular mortality[43]. However, further research is needed to clarify the benefits of these fats in patients with DKD[44].

Specific evidence-based diets offer a promising approach. The dietary approach to stop hypertension (DASH) diet was developed to lower blood pressure. However, it also reduces saturated fat intake and emphasizes plant-based foods, low-fat dairy, whole grains, and nuts. This dietary pattern improves low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, insulin sensitivity, and weight management[45]. Similarly, the Mediterranean diet emphasizes intake of olive oil, nuts, fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. It has been linked to better glycemic control and lower cardiovascular risk in patients with CKD and T2DM[46]. Traditional cuisine from the Arab Levantine (Palestine, Syria, Jordan, Lebanon), which includes culturally familiar foods such as hummus, tabbouleh, and grilled vegetables, aligns with the Mediterranean diet principles and offers a practical, culturally relevant way to improve cardiometabolic health while limiting harmful fat intake[47].

Potassium intake: Managing potassium intake is a critical component for individuals with T2DM and CKD. Diabetes independently increases the risk of hyperkalemia due to impaired potassium excretion and altered cellular shifts. This risk is further heightened by CKD, cardiovascular disease, advancing age, and the use of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors[48,49]. Hyperkalemia is defined by serum potassium levels over 5.0 mEq/L. It significantly elevates the risk of hospitalization and mortality in patients with heart failure and acute myocardial infarction, posing risks comparable to hypokalemia (< 3.5 mEq/L)[50].

As CKD progresses, MNT must adapt to changing nutritional needs. A patient in the early stages of CKD may tolerate a potassium-rich diet to address deficiencies. However, with disease progression, elevated serum potassium may necessitate dietary restrictions and medication adjustments. After a kidney transplantation potassium levels often normalize, and this potentially removes the need for dietary interventions[51]. These dynamic shifts underscore the need for ongoing oversight from a nephrology dietitian, who can tailor dietary guidance throughout the disease course[52].

While dietary potassium restriction is essential for managing hyperkalemia in patients with T2DM and CKD, an overgeneralized approach to restriction can exclude key components of traditional Middle Eastern diets. These diets are rich in potassium but also provide beneficial fiber and alkaline content to counteract metabolic acidosis, enhance bowel function, and support gut health[53]. A stepwise, individualized approach to potassium restriction that is led by a renal dietitian can maintain nutritional adequacy while mitigating hyperkalemia risk[54]. First non-dietary contributors such as hyperglycemia, acidosis, constipation, medications, and potassium-sparing diuretics must be addressed[55]. Then the patient can begin reducing low-nutrient potassium sources, such as fruit juice, chocolate, and potato chips, and modifying food preparation techniques like peeling, chopping, and boiling vegetables to lower their potassium content[55]. Empha

Another emerging concern is the food industry’s increasing reliance on potassium-based additives to reduce sodium content in processed foods. Many manufacturers have substituted sodium chloride with potassium chloride to maintain flavor in response to public health campaigns advocating for lower sodium intake[56]. However, foods now labelled as low-sodium may contain significantly higher levels of potassium than their regular counterparts. For example, reduced-sodium deli meats can contain up to 44% more potassium due to these additives[57]. Patients with CKD should be aware of this because potassium from additives is more bioavailable than from natural sources and may increase hyperkalemia risk[58]. Both patients and healthcare providers must be vigilant about hidden sources of potassium in processed foods to manage intake effectively and prevent adverse outcomes.

Phosphorus intake: Phosphorus is an essential mineral for cellular energy metabolism and skeletal integrity. It is regulated primarily by the kidneys, parathyroid hormone, and fibroblast growth factor-23[59,60]. In individuals with CKD reduced renal clearance impairs phosphorus excretion, leading to hyperphosphatemia. This condition along with unrestricted intake contributes to vascular calcification and increases the risk of CKD-related mineral and bone disorders[61]. Therefore, it is critical to manage dietary phosphorus intake. For healthy adults 700 mg/day is recommended. Children and pregnant women require higher levels. Patients undergoing hemodialysis need an increased amount of protein (1.2-1.4 g/kg/day), resulting in an estimated phosphorus intake of 1450-1600 mg/day[62].

Animal proteins and additives provide significant amounts of bioavailable phosphorus, with varying phosphorus-to-protein ratios. Control strategies include diet modification, phosphate binders, and dialysis. However, strict restrictions can lead to protein malnutrition, and there are limited data from patients with early CKD[59]. Phosphorus-rich foods often provide essential nutrients, complicating dietary restrictions without compromising nutrition. Widespread use of phosphorus additives, lack of labelling, and low awareness further challenge adherence and highlight the need for culturally sensitive guidance in DKD[63]. Education programs on phosphate restriction for patients undergoing hemo

Sodium intake: Sodium management is essential for patients with CKD and T2DM because of its role in controlling blood pressure, reducing cardiovascular risk, and slowing CKD progression[66]. High sodium intake exacerbates hypertension and fluid retention and increases the risk of cardiovascular events and kidney damage. Studies have linked elevated sodium consumption with heart failure and CKD progression[67]. Sodium restriction supported by dietary counselling and access to low-sodium foods significantly lowers blood pressure and reduces proteinuria, a key marker of kidney damage[68]. Current guidelines recommend restricting sodium intake to less than 2 g/day (about 5 g of salt), and gradual reductions can help patients adapt their taste preferences, promoting better adherence over time[67].

Many patients with CKD continue to excrete sodium at levels comparable to or exceeding those of the general population, indicating gaps in dietary adherence or ongoing high-risk behaviors[69]. Sodium restriction is beneficial for lowering blood pressure and enhancing the efficacy of renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors. The effects of sodium restriction are comparable to adding diuretics. However, it can also cause a slight decline in renal function due to neurohormonal activation or changes in renal blood flow[70].

The DASH-Sodium study evaluated the impact of sodium intake and the DASH diet on kidney function. The DASH diet alone had a minimal effect on eGFR. However, the combination of the DASH diet with low sodium intake led to a short-term decrease in eGFR[71]. This reduction may likely reflect reversible adaptive hemodynamics (e.g., reduced intraglomerular pressure) rather than actual kidney injury, as evidenced by stable long-term outcomes in the DASH-Sodium trial sub-analysis. Nonetheless, long-term studies are needed to confirm these effects. Furthermore, adherence to the DASH diet has been associated with a lower risk of developing CKD, supporting recommendations by the American Diabetes Association and Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes for diets rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and low-fat dairy.

Fluid intake: Fluid intake for patients with CKD and T2DM varies based on kidney function, dialysis modality for patients undergoing dialysis, and individual factors such as cardiac status[72]. Most people do not need to limit fluids until they reach stage 4 or 5 CKD. However, fluid needs can vary even at a late stage. Some patients may still produce urine even with reduced kidney function, while others may lose both filtration and fluid-removal capacity earlier. If urine production occurs, then fluid intake is typically acceptable[73]. Patients with heart failure require fluid restriction regardless of the CKD stage due to the risk of exacerbating heart stress and volume overload[74].

Fluid recommendations are further tailored according to the type of kidney replacement therapy. Patients undergoing hemodialysis often have strict fluid limits to prevent complications like cramping, high blood pressure, and cardiova

| Group | Fluid needs | Key notes |

| CKD stages 1–3 | Typically unrestricted | Adequate function; monitor for heart failure |

| CKD stages 4–5 (non-dialysis) | May need restriction | Depends on urine output and cardiac status |

| Heart failure (any stage) | Restriction often required | Prevent fluid overload regardless of CKD stage |

| Hemodialysis | Strict limits | Prevent complications from fluid shifts |

| Peritoneal dialysis | More liberal intake | Daily dialysis allows flexibility; monitor sodium/sugar intake |

Evidence-based diets and cultural adaptations: The implementation of several evidence-based diets has shown benefits for managing cardiometabolic and kidney health. However, cultural and practical considerations affect patient adherence[78]. The DASH diet effectively lowers blood pressure and improves insulin sensitivity, but its reliance on fresh produce and low-sodium foods may not align with all regional dietary patterns or food access[79]. Adapting it within the Levantine context can improve feasibility and acceptability. For example, grilled fish seasoned with sumac and lemon, whole grains like bulgur or freekeh, and salads such as fattoush made with reduced salt and generous herbs offer culturally resonant, DASH-aligned meals. Flavoring with za’atar, garlic, and citrus instead of salt helps preserve taste while supporting sodium reduction goals and improve compliance[80].

Similarly, the Mediterranean diet, rich in monounsaturated fats and anti-inflammatory components, has been associated with reduced inflammation and slower CKD progression[33]. To enhance affordability and cultural relevance in GCC settings, it can be adapted using traditional staples such as mujaddara (lentils and rice), tabbouleh prepared with modest olive oil, and baked falafel. These substitutions preserve the diet’s health benefits while improving accessibility and long-term adherence.

A plant-based diet also offers cardiometabolic benefits, such as improved glycemic control and reduced oxidative stress, while lowering the protein burden of the kidneys[81]. However, this diet requires careful planning to avoid deficiencies in iron, vitamin B12, and essential amino acids, and to manage electrolyte levels[82]. Practical strategies within the Levantine diet can support safe implementation. Dishes such as ful medames (fava beans), shorbat adas (lentil soup), and stuffed zucchini with vegetables offer protein from legumes, and soaking or boiling legumes can reduce potassium content[55]. Various dietary patterns are summarized in Table 4. Education is vital to help patients integrate these diets while respecting traditional preferences.

| Dietary pattern | Benefits | Challenges | Cultural adaptations |

| DASH diet | Lowers blood pressure; improves insulin sensitivity and glycemic control | Requires high adherence; limited access to fresh produce in some regions | Use grilled fish, bulgur, and herbs like za’atar/sumac instead of salt; emphasize traditional whole grains |

| Mediterranean diet | Reduces inflammation; improves kidney function; lowers T2DM/CKD risk | High cost of olive oil/seafood; unfamiliarity with dietary structure | Incorporate tabbouleh, hummus, grilled fish; adjust portion sizes; use local oils and nuts |

| Plant-based diet | High fiber for glycemic/gut health; reduces kidney protein load and inflammation | Risk of B12/iron deficiency; potential potassium/phosphorus imbalance in CKD | Include ful medames, vegetable stews, lentils/chickpeas; education on balanced inclusion of small meat portions |

Ramadan challenges: Ramadan fasting presents unique challenges for individuals with T2DM and CKD, particularly in hot climates or during extended daylight hours[83]. Although CKD puts patients at high-risk in fasting, many choose to fast anyway. Among patients with T2DM, 76% fast and increase the risk of glycemic complications[84]. However, evidence from East London suggests that an individualized risk assessment, medication adjustments, education, and close monitoring can increase the safety of fasting for those with stable stage 3 CKD and well-controlled T2DM[9]. The participants in that study experienced no significant changes in creatinine, HbA1c, or blood pressure, and adverse event rates were similar in the fasting and non-fasting groups. Nonetheless, the overall impact of fasting on kidney function remains unclear[54].

Regional guidelines from Morocco, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia recommend pre-Ramadan risk stratification based on eGFR thresholds (e.g., < 30 mL/minute/1.73 m² as high risk), proteinuria, comorbidities, and transplant status[9]. Fasting is generally considered safe for patients with CKD stages 1–3 and eGFR > 45 mL/minute/1.73 m², provided renal function is stable and dietary and pharmacologic adjustments are made. Patients with eGFR < 30, poorly controlled T2DM (HbA1c > 8%), or recent transplant are advised against fasting due to higher risks of acute kidney injury, electrolyte imbalance, and hypo and hyperglycemia[84]. Strategies for patients with comorbid T2DM and CKD who choose to fast are renal function monitoring, medication adjustment, and dietary modifications to maintain hydration and avoid electrolyte imbalances.

The 2024 RaK tool, validated in a United Arab Emirates-based cohort, showed that frailty, baseline eGFR < 45, and non-United Arab Emirates nationality independently predicted fasting-related adverse events[85]. Ultimately, fasting decisions require shared decision-making between patients, nephrologists, and dietitians. Personalized fasting plans should emphasize hydration, avoidance of nephrotoxic drugs, appropriate medication timing (e.g., suhoor vs iftar), and early intervention in the case of metabolic derangement. Table 5 summarizes recommendations on how to advice patients with T2DM and CKD regarding Ramadan fasting. Further research is needed in high-risk populations to define fasting thresholds and inform individualized care.

| Domain | Recommendation |

| Risk assessment | Perform individualized pre-Ramadan evaluation to understand risk and guide decision-making |

| Eligibility | Support fasting only for patients with stable CKD (stages 1–3) and well-controlled T2DM |

| Monitoring and safety | Monitor renal function and hydration status during Ramadan; advise breaking fast if clinical deterioration occurs |

| Care approach | Implement tailored plans with medication adjustments, hydration strategies, and diet guidance |

Comorbid T2DM and CKD demands individualized dietary management, particularly in the Arabian Gulf where cultural and religious practices significantly influence nutritional interventions. This review highlights the importance of tailored macronutrient/micronutrient adjustments, fluid/electrolyte balance, and culturally adapted strategies emphasizing plant-based proteins, reduced refined carbohydrates, and heart-healthy fats. Future research should prioritize region-specific interventions and technology integration (e.g., continuous glucose monitoring), while policymakers must estab

| 1. | Al-Ghamdi S, Abu-Alfa A, Alotaibi T, AlSaaidi A, AlSuwaida A, Arici M, Ecder T, El Koraie AF, Ghnaimat M, Hafez MH, Hassan M, Sqalli T. Chronic Kidney Disease Management in the Middle East and Africa: Concerns, Challenges, and Novel Approaches. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2023;16:103-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Aregawi K, Kabew Mekonnen G, Belete R, Kucha W. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease and associated factors among adult diabetic patients: a hospital-based cross-sectional study. Front Epidemiol. 2024;4:1467911. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chaudhry K, Karalliedde J. Chronic kidney disease in type 2 diabetes: The size of the problem, addressing residual renal risk and what we have learned from the CREDENCE trial. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2024;26 Suppl 5:25-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kalantar-Zadeh K, Fouque D. Nutritional Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1765-1776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 314] [Cited by in RCA: 430] [Article Influence: 47.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | de Boer IH, Khunti K, Sadusky T, Tuttle KR, Neumiller JJ, Rhee CM, Rosas SE, Rossing P, Bakris G. Diabetes Management in Chronic Kidney Disease: A Consensus Report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO). Diabetes Care. 2022;45:3075-3090. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 239] [Cited by in RCA: 487] [Article Influence: 121.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | American Diabetes Association. Introduction: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care. 2022;45:S1-S2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 241] [Article Influence: 60.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rhee CM, Wang AY, Biruete A, Kistler B, Kovesdy CP, Zarantonello D, Ko GJ, Piccoli GB, Garibotto G, Brunori G, Sumida K, Lambert K, Moore LW, Han SH, Narasaki Y, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Nutritional and Dietary Management of Chronic Kidney Disease Under Conservative and Preservative Kidney Care Without Dialysis. J Ren Nutr. 2023;33:S56-S66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | International Diabetes Federation. Middle East and North Africa. [cited 16 September 2025]. Available from: https://diabetesatlas.org/data-by-location/region/middle-east-and-north-africa/. |

| 9. | Naser AY, Alwafi H, Alotaibi B, Salawati E, Samannodi M, Alsairafi Z, Alanazi AFR, Dairi MS. Prevalence of Chronic Kidney Diseases in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus in the Middle East: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Endocrinol. 2021;2021:4572743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chowdhury A, Khan H, Lasker SS, Chowdhury TA. Fasting outcomes in people with diabetes and chronic kidney disease in East London during Ramadan 2018: The East London diabetes in Ramadan survey. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;152:166-170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ameer OZ. Hypertension in chronic kidney disease: What lies behind the scene. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:949260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Dasgupta I, Zac-Varghese S, Chaudhry K, McCafferty K, Winocour P, Chowdhury TA, Bellary S, Goldet G, Wahba M, De P, Frankel AH, Montero RM, Lioudaki E, Banerjee D, Mallik R, Sharif A, Kanumilli N, Milne N, Patel DC, Dhatariya K, Bain SC, Karalliedde J. Current management of chronic kidney disease in type-2 diabetes-A tiered approach: An overview of the joint Association of British Clinical Diabetologists and UK Kidney Association (ABCD-UKKA) guidelines. Diabet Med. 2025;42:e15450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | AlSahow A, AbdulShafy M, Al-Ghamdi S, AlJoburi H, AlMogbel O, Al-Rowaie F, Attallah N, Bader F, Hussein H, Hassan M, Taha K, Weir MR, Zannad F. Prevalence and management of hyperkalemia in chronic kidney disease and heart failure patients in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2023;25:251-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bhatt AA, Choudhari PK, Mahajan RR, Sayyad MG, Pratyush DD, Hasan I, Javherani RS, Bothale MM, Purandare VB, Unnikrishnan AG. Effect of a Low-Calorie Diet on Restoration of Normoglycemia in Obese subjects with Type 2 Diabetes. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2017;21:776-780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ding X, Li X, Ye Y, Jiang J, Lu M, Shao L. Epidemiological patterns of chronic kidney disease attributed to type 2 diabetes from 1990-2019. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2024;15:1383777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Moore LW, Byham-Gray LD, Scott Parrott J, Rigassio-Radler D, Mandayam S, Jones SL, Mitch WE, Osama Gaber A. The mean dietary protein intake at different stages of chronic kidney disease is higher than current guidelines. Kidney Int. 2013;83:724-732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Campbell AP, Rains TM. Dietary protein is important in the practical management of prediabetes and type 2 diabetes. J Nutr. 2015;145:164S-169S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Koppe L, Fouque D. The Role for Protein Restriction in Addition to Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System Inhibitors in the Management of CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;73:248-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Friedman AN. High-protein diets: potential effects on the kidney in renal health and disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44:950-962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Jin H, Huang L, Ye J, Wang J, Lin X, Wu S, Hu W, Lin Q, Li X. Enhancing nutritional management in peritoneal dialysis patients through a generative pre-trained transformers-based recipe generation tool: a pilot study. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024;11:1469227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Ria P, De Pascalis A, Zito A, Barbarini S, Napoli M, Gigante A, Sorice GP. Diet and Proteinuria: State of Art. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;24:44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bawazir A, Topf JM, Hiremath S. Protein restriction in CKD: an outdated strategy in the modern era. J Bras Nefrol. 2025;47:e2024PO03. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Anderson JW. Beneficial effects of soy protein consumption for renal function. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2008;17 Suppl 1:324-328. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Lew QJ, Jafar TH, Koh HW, Jin A, Chow KY, Yuan JM, Koh WP. Red Meat Intake and Risk of ESRD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:304-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 17.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Chen X, Wei G, Jalili T, Metos J, Giri A, Cho ME, Boucher R, Greene T, Beddhu S. The Associations of Plant Protein Intake With All-Cause Mortality in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;67:423-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Gan T, Liu X, Xu G. Glycated Albumin Versus HbA1c in the Evaluation of Glycemic Control in Patients With Diabetes and CKD. Kidney Int Rep. 2018;3:542-554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Triozzi JL, Parker Gregg L, Virani SS, Navaneethan SD. Management of type 2 diabetes in chronic kidney disease. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2021;9:e002300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hahr AJ, Molitch ME. Management of Diabetes Mellitus in Patients With CKD: Core Curriculum 2022. Am J Kidney Dis. 2022;79:728-736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Heo GY, Koh HB, Kim HW, Park JT, Yoo TH, Kang SW, Kim J, Kim SW, Kim YH, Sung SA, Oh KH, Han SH. Glycemic Control and Adverse Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Results from KNOW-CKD. Diabetes Metab J. 2023;47:535-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kang DH, Streja E, You AS, Lee Y, Narasaki Y, Torres S, Novoa-Vargas A, Kovesdy CP, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Rhee CM. Hypoglycemia and Mortality Risk in Incident Hemodialysis Patients. J Ren Nutr. 2024;34:200-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Sami W, Alabdulwahhab KM, Ab Hamid MR, Alasbal TA, Al Alwadani F, Ahmad MS. (2020). Dietary habits of type 2 diabetes patients: Frequency and diversity of nutrition intake – Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Prog Nutr. 2020;22:521-527. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 32. | Shukla AP, Andono J, Touhamy SH, Casper A, Iliescu RG, Mauer E, Shan Zhu Y, Ludwig DS, Aronne LJ. Carbohydrate-last meal pattern lowers postprandial glucose and insulin excursions in type 2 diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2017;5:e000440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Ren Q, Zhou Y, Luo H, Chen G, Han Y, Zheng K, Qin Y, Li X. Associations of low-carbohydrate with mortality in chronic kidney disease. Ren Fail. 2023;45:2202284. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Pérez-Torres A, Caverni-Muñoz A, González García E. Mediterranean Diet and Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD): A Practical Approach. Nutrients. 2022;15:97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Laiteerapong N, Ham SA, Gao Y, Moffet HH, Liu JY, Huang ES, Karter AJ. The Legacy Effect in Type 2 Diabetes: Impact of Early Glycemic Control on Future Complications (The Diabetes & Aging Study). Diabetes Care. 2019;42:416-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 363] [Cited by in RCA: 405] [Article Influence: 57.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Juray S, Axen KV, Trasino SE. Remission of Type 2 Diabetes with Very Low-Calorie Diets-A Narrative Review. Nutrients. 2021;13:2086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Steven S, Hollingsworth KG, Al-Mrabeh A, Avery L, Aribisala B, Caslake M, Taylor R. Very Low-Calorie Diet and 6 Months of Weight Stability in Type 2 Diabetes: Pathophysiological Changes in Responders and Nonresponders. Diabetes Care. 2016;39:808-815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 249] [Cited by in RCA: 279] [Article Influence: 27.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Said S, Hernandez GT. The link between chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease. J Nephropathol. 2014;3:99-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Jankowski J, Floege J, Fliser D, Böhm M, Marx N. Cardiovascular Disease in Chronic Kidney Disease: Pathophysiological Insights and Therapeutic Options. Circulation. 2021;143:1157-1172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 531] [Cited by in RCA: 1308] [Article Influence: 261.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 40. | Grundy SM, Stone NJ, Bailey AL, Beam C, Birtcher KK, Blumenthal RS, Braun LT, de Ferranti S, Faiella-Tommasino J, Forman DE, Goldberg R, Heidenreich PA, Hlatky MA, Jones DW, Lloyd-Jones D, Lopez-Pajares N, Ndumele CE, Orringer CE, Peralta CA, Saseen JJ, Smith SC Jr, Sperling L, Virani SS, Yeboah J. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:3168-3209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 634] [Cited by in RCA: 1282] [Article Influence: 160.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Sacks FM, Lichtenstein AH, Wu JHY, Appel LJ, Creager MA, Kris-Etherton PM, Miller M, Rimm EB, Rudel LL, Robinson JG, Stone NJ, Van Horn LV; American Heart Association. Dietary Fats and Cardiovascular Disease: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;136:e1-e23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 627] [Cited by in RCA: 926] [Article Influence: 102.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | United States Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025. [cited 16 September 2025]. Available from: https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/tools-action/browse-evidence-based-resources/dietary-guidelines-americans-2020-2025. |

| 43. | Harris WS, Mozaffarian D, Rimm E, Kris-Etherton P, Rudel LL, Appel LJ, Engler MM, Engler MB, Sacks F. Omega-6 fatty acids and risk for cardiovascular disease: a science advisory from the American Heart Association Nutrition Subcommittee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and Council on Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation. 2009;119:902-907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 536] [Cited by in RCA: 555] [Article Influence: 32.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Guasch-Ferré M, Babio N, Martínez-González MA, Corella D, Ros E, Martín-Peláez S, Estruch R, Arós F, Gómez-Gracia E, Fiol M, Santos-Lozano JM, Serra-Majem L, Bulló M, Toledo E, Barragán R, Fitó M, Gea A, Salas-Salvadó J; PREDIMED Study Investigators. Dietary fat intake and risk of cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality in a population at high risk of cardiovascular disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;102:1563-1573. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 21.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Kochan Z, Szupryczynska N, Malgorzewicz S, Karbowska J. Dietary Lipids and Dyslipidemia in Chronic Kidney Disease. Nutrients. 2021;13:3138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Siervo M, Lara J, Chowdhury S, Ashor A, Oggioni C, Mathers JC. Effects of the Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension (DASH) diet on cardiovascular risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Nutr. 2015;113:1-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 256] [Cited by in RCA: 380] [Article Influence: 31.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Esposito K, Maiorino MI, Bellastella G, Panagiotakos DB, Giugliano D. Mediterranean diet for type 2 diabetes: cardiometabolic benefits. Endocrine. 2017;56:27-32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Azizi F, Hadaegh F, Hosseinpanah F, Mirmiran P, Amouzegar A, Abdi H, Asghari G, Parizadeh D, Montazeri SA, Lotfaliany M, Takyar F, Khalili D. Metabolic health in the Middle East and north Africa. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7:866-879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Sarnowski A, Gama RM, Dawson A, Mason H, Banerjee D. Hyperkalemia in Chronic Kidney Disease: Links, Risks and Management. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2022;15:215-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Goia-Nishide K, Coregliano-Ring L, Rangel ÉB. Hyperkalemia in Diabetes Mellitus Setting. Diseases. 2022;10:20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Hougen I, Leon SJ, Whitlock R, Rigatto C, Komenda P, Bohm C, Tangri N. Hyperkalemia and its Association With Mortality, Cardiovascular Events, Hospitalizations, and Intensive Care Unit Admissions in a Population-Based Retrospective Cohort. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;6:1309-1316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Clegg DJ, Headley SA, Germain MJ. Impact of Dietary Potassium Restrictions in CKD on Clinical Outcomes: Benefits of a Plant-Based Diet. Kidney Med. 2020;2:476-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Ikizler TA, Burrowes JD, Byham-Gray LD, Campbell KL, Carrero JJ, Chan W, Fouque D, Friedman AN, Ghaddar S, Goldstein-Fuchs DJ, Kaysen GA, Kopple JD, Teta D, Yee-Moon Wang A, Cuppari L. KDOQI Clinical Practice Guideline for Nutrition in CKD: 2020 Update. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;76:S1-S107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 837] [Cited by in RCA: 1185] [Article Influence: 197.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 54. | Cases A, Cigarrán-Guldrís S, Mas S, Gonzalez-Parra E. Vegetable-Based Diets for Chronic Kidney Disease? It Is Time to Reconsider. Nutrients. 2019;11:1263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | AlSahow A. Moderate stepwise restriction of potassium intake to reduce risk of hyperkalemia in chronic kidney disease: A literature review. World J Nephrol. 2023;12:73-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 56. | MacLaughlin HL, Friedman AN, Ikizler TA. Nutrition in Kidney Disease: Core Curriculum 2022. Am J Kidney Dis. 2022;79:437-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Nurmilah S, Cahyana Y, Utama GL, Aït-Kaddour A. Strategies to Reduce Salt Content and Its Effect on Food Characteristics and Acceptance: A Review. Foods. 2022;11:3120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Martínez-Pineda M, Vercet A, Yagüe-Ruiz C. Are Food Additives a Really Problematic Hidden Source of Potassium for Chronic Kidney Disease Patients? Nutrients. 2021;13:3569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Stubbs J, Liu S, Quarles LD. Role of fibroblast growth factor 23 in phosphate homeostasis and pathogenesis of disordered mineral metabolism in chronic kidney disease. Semin Dial. 2007;20:302-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Shaman AM, Kowalski SR. Hyperphosphatemia Management in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease. Saudi Pharm J. 2016;24:494-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Saxena A, Sachan T, Gupta A, Kapoor V. Effect of Dietary Phosphorous Restriction on Fibroblast Growth 2 Factor-23 and sKlotho Levels in Patients with Stages 1-2 Chronic Kidney Disease. Nutrients. 2022;14:3302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Barreto FC, Barreto DV, Massy ZA, Drüeke TB. Strategies for Phosphate Control in Patients With CKD. Kidney Int Rep. 2019;4:1043-1056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | González-Parra E, Gracia-Iguacel C, Egido J, Ortiz A. Phosphorus and nutrition in chronic kidney disease. Int J Nephrol. 2012;2012:597605. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Lou-Arnal LM, Arnaudas-Casanova L, Caverni-Muñoz A, Vercet-Tormo A, Caramelo-Gutiérrez R, Munguía-Navarro P, Campos-Gutiérrez B, García-Mena M, Moragrera B, Moreno-López R, Bielsa-Gracia S, Cuberes-Izquierdo M; Grupo de Investigación ERC Aragón. Hidden sources of phosphorus: presence of phosphorus-containing additives in processed foods. Nefrologia. 2014;34:498-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Yin J, Yin J, Lian R, Li P, Zheng J. Implementation and effectiveness of an intensive education program on phosphate control among hemodialysis patients: a non-randomized, single-arm, single-center trial. BMC Nephrol. 2021;22:243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Ashurst Ide B, Dobbie H. A randomized controlled trial of an educational intervention to improve phosphate levels in hemodialysis patients. J Ren Nutr. 2003;13:267-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Mills KT, Chen J, Yang W, Appel LJ, Kusek JW, Alper A, Delafontaine P, Keane MG, Mohler E, Ojo A, Rahman M, Ricardo AC, Soliman EZ, Steigerwalt S, Townsend R, He J; Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study Investigators. Sodium Excretion and the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease. JAMA. 2016;315:2200-2210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 175] [Article Influence: 17.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Denker M, Boyle S, Anderson AH, Appel LJ, Chen J, Fink JC, Flack J, Go AS, Horwitz E, Hsu CY, Kusek JW, Lash JP, Navaneethan S, Ojo AO, Rahman M, Steigerwalt SP, Townsend RR, Feldman HI; Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Study Investigators. Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Study (CRIC): Overview and Summary of Selected Findings. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10:2073-2083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Al Saleh S, Dobre M, DeLozier S, Perez J, Patil N, Rahman M, Pradhan N. Isolated Diastolic Hypertension and Kidney and Cardiovascular Outcomes in CKD: The Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study. Kidney Med. 2023;5:100728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Humalda JK, Navis G. Dietary sodium restriction: a neglected therapeutic opportunity in chronic kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2014;23:533-540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | O'Callaghan CA. Dietary salt intake in chronic kidney disease: recent studies and their practical implications. Pol Arch Intern Med. 2024;134:16715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Morales-Alvarez MC, Nissaisorakarn V, Appel LJ, Miller ER 3rd, Christenson RH, Rebuck H, Rosas SE, William JH, Juraschek SP. Effects of Reduced Dietary Sodium and the DASH Diet on GFR: The DASH-Sodium Trial. Kidney360. 2024;5:569-576. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Lambert K, Neale E, Nichols L, Brauer D, Blomfield R, Caurana L, Isautier J, Jesudason S, Webster AC. Interventions for improving adherence to dietary salt and fluid restrictions in people with chronic kidney disease (stage 4 and 5). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;2022. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 75. | Segall L, Nistor I, Covic A. Heart failure in patients with chronic kidney disease: a systematic integrative review. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:937398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Brown M, Burrows L, Pruett T, Burrows T. Hemodialysis-Induced Myocardial Stunning: A Review. Nephrol Nurs J. 2015;42:59-66; quiz 67. [PubMed] |

| 77. | Zheng S, Auguste BL. Five Things to Know About Volume Overload in Peritoneal Dialysis. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2023;10:20543581221150590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Castera MR, Borhade MB. Fluid Management. 2025 Apr 29. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2025. [PubMed] |

| 79. | Wang W, Liu Y, Li Y, Luo B, Lin Z, Chen K, Liu Y. Dietary patterns and cardiometabolic health: Clinical evidence and mechanism. MedComm (2020). 2023;4:e212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Ramesh G, Wood AC, Allison MA, Rich SS, Jensen ET, Chen YI, Rotter JI, Bertoni AG, Goodarzi MO. Associations between adherence to the dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH) diet and six glucose homeostasis traits in the Microbiome and Insulin Longitudinal Evaluation Study (MILES). Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2022;32:1418-1426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Dougkas A, Vannereux M, Giboreau A. The Impact of Herbs and Spices on Increasing the Appreciation and Intake of Low-Salt Legume-Based Meals. Nutrients. 2019;11:2901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Kahleova H, Levin S, Barnard N. Cardio-Metabolic Benefits of Plant-Based Diets. Nutrients. 2017;9:848. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 196] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Zarantonello D, Brunori G. The Role of Plant-Based Diets in Preventing and Mitigating Chronic Kidney Disease: More Light than Shadows. J Clin Med. 2023;12:6137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Hassanein M, Yousuf S, Ahmedani MY, Albashier A, Shaltout I, Yong A, Hafidh K, Hussein Z, Kallash MA, Aljohani N, Wong HC, Buyukbese MA, Chowdhury T, Fadhila MERZOUKI, Taher SW, Belkhadir J, Malek R, Abdullah NRA, Shaikh S, Alabbood M. Ramadan fasting in people with diabetes and chronic kidney disease (CKD) during the COVID-19 pandemic: The DaR global survey. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2023;17:102799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Boobes Y, Afandi B, AlKindi F, Tarakji A, Al Ghamdi SM, Alrukhaimi M, Hassanein M, AlSahow A, Said R, Alsaid J, Alsuwaida AO, Al Obaidli AAK, Alketbi LB, Boubes K, Attallah N, Al Salmi IS, Abdelhamid YM, Bashir NM, Aburahma RMY, Hassan MH, Al-Hakim MR. Consensus recommendations on fasting during Ramadan for patients with kidney disease: review of available evidence and a call for action (RaK Initiative). BMC Nephrol. 2024;25:84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/