Published online Sep 25, 2025. doi: 10.5527/wjn.v14.i3.107955

Revised: April 22, 2025

Accepted: June 23, 2025

Published online: September 25, 2025

Processing time: 169 Days and 14.1 Hours

Hydatid disease, caused by the Echinococcus granulosus parasite, is traditionally associated with liver and lung involvement. However, recent years have seen an increase in cases with atypical localizations, such as the kidneys, thyroid, soft tissues, and bones. The study by Celik et al presents a series of five clinical cases where hydatid cysts were found in these rare anatomical regions, challenging conventional diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. The paper emphasizes the importance of differential diagnosis, as these cases can mimic other conditions, such as cancer, abscesses, or cysts. Advanced imaging techniques, such as com

Core Tip: Hydatid disease in atypical anatomical sites presents significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges due to its rarity and variable clinical manifestations. This editorial summarizes the current evidence on cystic echinococcosis in unusual localizations, emphasizing imaging strategies, surgical management, and the limitations of serological testing. The paper also critiques a recent case series by Celik et al, underlining the importance of multidisciplinary care and standardized reporting in these complex scenarios.

- Citation: Semash K, Voskanov M. Diagnostic challenges and treatment approaches for hydatid cysts in atypical localizations. World J Nephrol 2025; 14(3): 107955

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-6124/full/v14/i3/107955.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5527/wjn.v14.i3.107955

Echinococcosis is a parasitic disease caused by the larval stage of the tapeworm Echinococcus granulosus[1]. The main intermediate hosts are livestock (such as sheep and goats), while the definitive hosts are dogs and other carnivores. Humans become infected accidentally through ingestion of parasite eggs via contaminated food, water, or direct contact with infected animals. Once inside the human body, the eggs transform into larvae that migrate through the portal vein or lymphatic system, forming cysts in various organs[2].

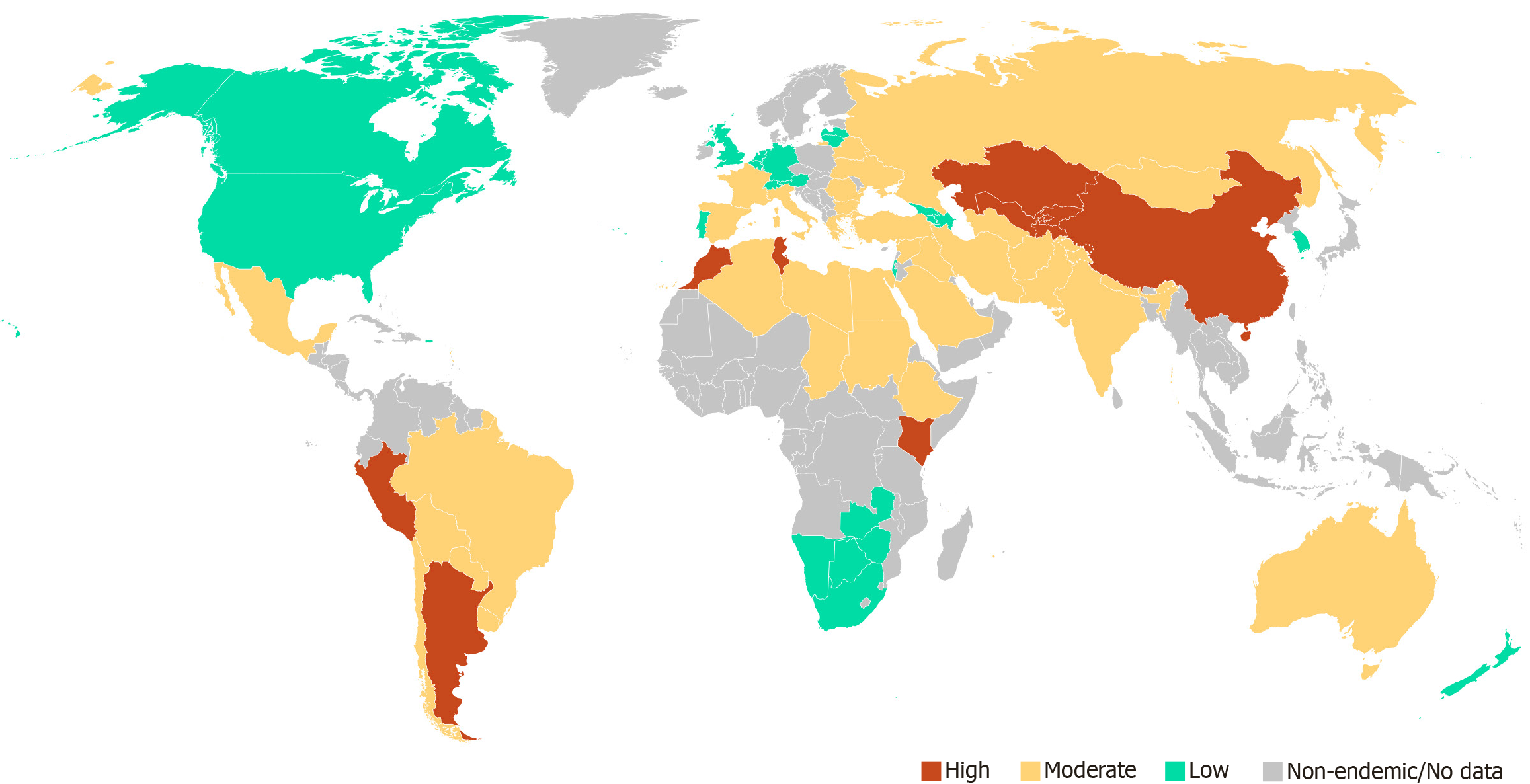

According to literature data, renal hydatid cysts occur in 1%-3% of cases, osseous involvement in fewer than 2%, while involvement of the thyroid, pancreas, soft tissues, facial bones, and other unusual sites is mostly limited to isolated case reports. In endemic regions such as Turkey, Iran, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, North Africa, and South America, the incidence of echinococcosis may reach 6-30 cases per 100000 population annually and exceed 50 per 100000 in some rural areas (Figure 1)[2-4]. In resource-limited countries, accurate disease surveillance and epidemiological monitoring are often difficult, leading to underestimation of the true disease burden. Similarly, limited access to diagnostic tools—especially imaging and laboratory confirmation—can result in missed or incorrect diagnoses[1-3].

The most common localizations of hydatid cysts are the liver (up to 65%-70% of cases) and lungs (20%-25%)[2]. These forms are well-studied and benefit from standardized diagnostic algorithms and treatment protocols. However, echinococcosis can affect nearly any organ, including the kidneys, spleen, brain, heart, bones, pancreas, thyroid gland, and soft tissues[5]. These rare (atypical) forms pose significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges for clinicians.

Recent literature emphasizes the increasing clinical relevance of hydatid disease in atypical anatomical locations beyond the liver and lungs. Shahriarirad et al[5] reported that up to 9.2% of echinococcosis cases involve unusual sites such as the spleen, pelvis, bones, and soft tissues, emphasizing the diagnostic variety. Alekya et al[6] documented similar presentations in the orbit, breast, retroperitoneum, and muscles. Bennane et al[7] described disseminated involvement including the liver, kidneys, mediastinum, and pancreas, stressing the limited sensitivity of serological tests in extrahepatic disease. Gader et al[8] presented an extremely rare brainstem hydatid cyst in a child, successfully treated with surgery and albendazole. Yordanov et al[9] reported a case of pelvic hydatid disease mimicking gynecologic pathology, while Di Giambenedetto et al[10] documented retroperitoneal disease in a non-endemic region, highlighting the global need for clinical suspicion. Celik et al[11] presented a case series involving the kidney, thyroid gland, bones, and soft tissue, highlighting the diagnostic challenge posed by atypical cystic lesions. Collectively, these studies underscore the need for a multidisciplinary approach, relying on advanced imaging, targeted serology, and tailored surgical and pharmacological strategies—particularly in resource-limited settings.

Rare forms of echinococcosis often mimic other conditions, such as tumors, abscesses, cysts, or fibrotic lesions. This can lead to diagnostic errors and delayed treatment[12].

Diagnosis of echinococcosis relies on a combination of clinical history, epidemiological context, serological tests, and imaging. The key imaging modalities are ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)[1,12]. CT is particularly effective in detecting calcifications, daughter cysts, and multivesicular architecture, making it the preferred modality for evaluating osseous and thoracoabdominal involvement[13]. MRI provides superior soft tissue contrast and is indispensable for assessing lesions in the brain, spinal cord, or musculature. In hepatic and pelvic disease, MRI can delineate cyst morphology and adjacent organ invasion with high precision. Both modalities not only support the diagnosis but also aid in surgical planning by accurately mapping the extent of the disease. Integration of imaging data with clinical and serological findings is essential for the comprehensive evaluation and management of patients with suspected echinococcosis.

Ultrasonography is a crucial first-line tool in endemic regions for evaluating cystic thyroid nodules, and when echinococcosis is suspected, fine-needle aspiration (FNA) should be avoided due to the risk of cyst rupture[14].

Diagnosis of complicated and rare forms of echinococcosis presents significant challenges, particularly in the presence of secondary changes within the cyst structure. The development of superinfection, intracystic hemorrhage, or rupture into the biliary tract, peritoneal cavity, or surrounding tissues can significantly alter the ultrasound and tomographic appearance, potentially leading to diagnostic errors[15]. Diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for rare forms of echinococcosis—those occurring outside the liver and lungs—require a tailored, case-specific approach due to their atypical clinical and radiological presentations. As highlighted in multiple case-based studies, uncommon localizations such as the kidneys, bones, central nervous system, thyroid gland, and soft tissues often mimic neoplastic, inflammatory, or congenital lesions[5-11]. Therefore, differential diagnosis plays a central role, and radiological imaging becomes the cornerstone of evaluation. In rare cases, where imaging findings are inconclusive, FNA or biopsy may be considered cautiously, although it carries a risk of cyst rupture and dissemination. The authors emphasize that diagnostic difficulty increases in the absence of an informative clinical history and when typical features of echinococcosis are lacking.

In their comprehensive imaging-based review, Srinivas et al[13] underscore the diagnostic complexity of hydatid disease in unusual anatomical locations, particularly due to its ability to mimic neoplastic, cystic, or infectious processes. The authors highlight that the radiological appearance of cystic echinococcosis varies significantly across organ systems, often lacking classical features when located outside the liver and lungs. Notably, they emphasize the role of multiplanar MRI in characterizing cystic lesions in the central nervous system and musculoskeletal tissues, where ultrasound is often limited. Moreover, the paper draws attention to specific complications such as internal rupture and superinfection, which can alter typical imaging patterns and further delay diagnosis. Their analysis suggests that awareness of these atypical imaging signatures, combined with high clinical suspicion in endemic regions, is critical to avoid misdiagnosis and unnecessary invasive procedures. These insights reinforce the need for radiologists to consider hydatid disease even in highly unusual presentations.

Aledavoud et al[16] conducted a systematic review of 75 reported cases of thyroid hydatid cysts from 57 publications, highlighting the extreme rarity and diagnostic challenge of this localization. The majority of patients presented with a slowly enlarging cervical mass (94.5%), with the left thyroid lobe being more frequently involved. Ultrasound was the primary diagnostic tool, revealing cystic nodules in over 90% of cases, though in some instances the findings mimicked neoplastic lesions.

In a retrospective study, Shahriarirad et al[5] reported 46 cases of cystic echinococcosis involving rare anatomical sites among 501 surgically managed patients in Southern Iran. The most frequently affected atypical organs included the spleen (43.5%), pancreas, pelvic cavity, ovary, brain, spine, and mediastinum. The authors underscore that these uncommon sites often lead to misdiagnosis, with many cases initially suspected as malignancies or abscesses. Cross-sectional imaging, particularly CT and MRI, was pivotal in preoperative identification and planning.

Mutafchiyski et al[17] conducted a systematic review identifying 121 cases of breast CE, with only 52 providing sufficient clinical and diagnostic information. The majority of patients were women with a mean age of 40.5 years. The clinical presentation was typically a slowly growing, painless lump, often present for years prior to diagnosis. Ultrasound was the most frequently employed diagnostic tool (83%), while mammography and FNA were also utilized, though FNA yielded definitive findings in only 59% of cases and carried risks of dissemination. Most cysts were classified as active (CL and CE1-2 stages). Notably, in contrast to hepatic or pulmonary CE, the breast’s anatomical accessibility makes complete surgical excision the preferred and most effective treatment option. The authors recommend total cystectomy as the gold standard for diagnosis and management, with limited justification for albendazole therapy in isolated cases without dissemination. This study highlights both the diagnostic challenges and the clear therapeutic strategy for this rare localization.

Serological diagnosis includes several techniques, each with varying sensitivity depending on the cyst location. The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is widely used due to its high sensitivity (up to 95%) for hepatic echinococcosis, but its accuracy decreases significantly for extrahepatic sites, sometimes falling below 50%[2]. Indirect hemagglutination (IHA) provides complementary diagnostic support but can yield false positives in other parasitic diseases[14]. Immunoblotting (Western blot) is highly specific and useful for confirming equivocal ELISA or IHA results, especially in complex clinical scenarios. In extrahepatic or atypical cases, serological results should be interpreted cautiously and in conjunction with imaging and epidemiological context[2,14,17]. Despite its diagnostic value in hepatic echinococcosis, serological testing—especially ELISA—demonstrates significantly reduced sensitivity in atypical localizations, with some studies reporting rates below 50%. This limitation is particularly evident in subcutaneous, osseous, and central nervous system involvements, where the immune response may be muted or nonspecific[2,14]. Consequently, negative serologic results cannot reliably exclude echinococcosis in patients with compatible imaging and clinical context. Physicians should be cautious when interpreting serology in these cases and rely on integrative diagnostic approaches. Overall, the limited reliability of serology in non-hepatic echinococcosis underscores the essential role of radiological imaging in diagnostic confirmation.

However, the diagnosis cannot always be made based on the available diagnostic capabilities. Thus, Kbir et al[18] presented a rare case of a primary gallbladder hydatid cyst, accounting for less than 0.4% of all echinococcosis cases. The diagnosis was made intraoperatively, as preoperative imaging could not reliably distinguish the lesion’s origin[18]. Koppen et al[19] described the first case of alveolar echinococcosis involving the parotid gland, highlighting the diagnostic complexity due to atypical localization and non-specific clinical presentation. Imaging, including MRI, was crucial for identifying the lesion, but definitive diagnosis relied on histopathology and immunohistochemistry[19].

Ramos Pascua et al[20] and Chablou et al[21] presented a rare case of subcutaneous echinococcosis localized to the gluteal region in patients from an endemic area. The diagnostic process was challenging due to the non-specific clinical presentation and limited sensitivity of serological testing for soft tissue involvement. Imaging techniques, particularly MRI and CT, were essential in visualizing the cystic structure, although the features could mimic other soft tissue pathologies such as abscesses or tumors.

All these studies reinforce the diagnostic complexity and surgical importance of managing hydatid disease in rare localizations.

The treatment of echinococcosis is multimodal. Management strategies for cystic echinococcosis must be individualized and guided by cyst stage, localization, patient condition, and available resources. According to WHO guidelines, observation (“watch and wait”) is appropriate for asymptomatic patients with small (< 5 cm), calcified, or degenerative cysts (CE4-CE5), especially in elderly or high-risk patients. This conservative approach includes serial imaging (CT or ultrasound every 3-6 months for the first two years, then annually), serologic monitoring, and clinical follow-up[1].

Medical therapy with albendazole is indicated for cysts measuring 5-7 cm, inoperable cases, patients with multiple cysts, or when there is a high risk of intraoperative dissemination. Albendazole is also used as perioperative prophylaxis (4-6 weeks before and up to 3 months after surgery)[1,12,22]. The standard dosage is 10-15 mg/kg/day in two divided doses, administered in 28-day cycles with 14-day breaks. Treatment monitoring includes liver function tests, leukocyte counts, and periodic imaging.

In selected cases, particularly involving accessible cysts in the abdominal cavity or soft tissues, the puncture, aspiration, injection, and reaspiration (PAIR) technique may be considered as a minimally invasive treatment option[1]. This ultrasound- or CT-guided procedure is generally reserved for patients with uncomplicated cysts who are either unfit for surgery or in whom surgery poses excessive risk. PAIR has demonstrated good outcomes in hepatic disease and may be cautiously extrapolated to rare localizations, provided there is no communication with hollow organs or evidence of cyst wall calcification. Nevertheless, its use is contraindicated in osseous, central nervous system, or superficially located cysts due to the high risk of leakage, dissemination, and anaphylaxis. Comprehensive preprocedural imaging is essential for patient selection[12,22].

Surgery remains the mainstay for symptomatic, complicated, or high-risk cysts. Indications include cyst rupture, infection, compression of adjacent structures, and locations with high rupture risk (e.g., brain, spine, bones)[22]. Radical pericystectomy is preferred when feasible. Partial resection is reserved for anatomically complex cases. Laparoscopic approaches are possible for accessible locations such as the liver and spleen[2]. Intraoperative use of scolicidal agents (e.g., hypertonic saline, povidone-iodine) and continuation of antiparasitic therapy in the postoperative period are strongly recommended to reduce recurrence[1].

Surgical management of hydatid cysts in rare locations requires meticulous preoperative planning, particularly for the involvement of bones, kidneys, the central nervous system, soft tissues, and the thyroid gland[14,16,22-24]. Whenever feasible, organ-preserving approaches are preferred, including complete or partial pericystectomy. Bone involvement may necessitate resection followed by reconstruction or prosthetic replacement[9,23]. Neck and soft tissue surgeries demand oncological precautions due to the risk of cyst rupture and dissemination of protoscolices[14]. On the other hand, despite the risk of cyst rupture and anaphylaxis, FNA biopsy was performed in approximately 28% of thyroid involvement cases, as reported by Aledavoud et al[16] Surgical treatment—ranging from lobectomy to total thyroidectomy—remains the mainstay of therapy, often complemented by albendazole administration.

The overall prognosis of patients with cystic echinococcosis in atypical or rare anatomical sites largely depends on the timing of diagnosis, the involved organ, and the adequacy of treatment[2,4]. In general, when diagnosed early and treated appropriately, the outcomes are favorable in most cases. However, rare localizations present unique challenges.

A favorable prognosis is typically observed in superficial localizations (e.g., subcutaneous tissue, breast, thyroid), where surgical excision is feasible and complete removal is possible[14,17,21,22]. Most reported cases in the literature involving these sites achieved full recovery without recurrence. Intermediate prognosis is often seen in deeper structures such as the spleen, pancreas, mediastinum, and retroperitoneum. These locations may lead to delayed diagnosis due to nonspecific symptoms and a higher risk of intraoperative spillage or recurrenceх[5,22]. Nonetheless, with proper surgical planning and adjunctive albendazole therapy, good outcomes are still achievable.

An unfavorable prognosis may be associated with involvement of the central nervous system, heart, bones, or spinal canal. These sites are associated with higher risks of complications such as rupture, neurological deficits, or anaphylaxis[24,25]. Surgery in these areas is often complex, and recurrence rates may be higher. In bone echinococcosis, in particular, the disease tends to be infiltrative and relapsing, requiring prolonged treatment and sometimes multiple interventions[26].

Delays in diagnosis, particularly in non-endemic countries or among non-specialist clinicians, can worsen outcomes due to complications such as infection, rupture, or mass effect[1-4]. Recurrence risk is reported in up to 10-20% of rare-location CE cases, especially if surgery was incomplete or there was intraoperative spillage. Mortality is low when managed properly but can increase significantly in cases involving the brain, heart, or disseminated disease[1].

The report by Celik et al[11] is valuable in illustrating the diversity of possible localizations and reinforces the importance of considering echinococcosis in the differential diagnosis, even in the absence of classic symptoms. The article is well-illustrated, and each case is accompanied by imaging, enhancing clinical insight. However, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the article does not include descriptions of surgical strategies or antiparasitic protocols used. Second, there is no follow-up data, making it difficult to assess the efficacy and safety of the chosen approaches. Third, the discussion lacks sufficient detail on differential diagnosis, laboratory confirmation, and specific challenges of surgical planning in complex anatomical areas.

Despite these limitations, the article by Celik et al[11] offers practical value to clinicians and highlights the importance of clinical awareness regarding atypical echinococcosis. The authors convey a key message: Management of unusual hydatid disease requires a multidisciplinary team involving infectious disease specialists, radiologists, surgeons, and, when necessary, oncologists. Treatment decisions should be based on cyst location, size, viability, and overall patient condition. The development of clear management algorithms and case registries is crucial for improving outcomes. The case series by Celik et al[11] holds particular clinical relevance for practitioners in endemic regions, where atypical presentations may be overlooked. By highlighting diverse localizations and imaging findings, the study reinforces the need to incorporate hydatid disease into differential diagnoses for cystic or tumor-like lesions, potentially prompting earlier imaging and referral. This may contribute to the refinement of local diagnostic algorithms and treatment protocols.

Therapeutically, surgery remains the mainstay for most rare echinococcal localizations, particularly when cysts are symptomatic, rapidly enlarging, or pose a risk of rupture[27]. Radical excision (e.g., pericystectomy, en bloc resection) is the preferred strategy, although technical complexity varies by location—neurosurgical intervention for brain cysts, orthopedic stabilization for osseous forms, or organ-preserving resection for thyroid or urogenital involvement. Table 1 summarizes current diagnostic and treatment strategies for rare hydatid localizations, integrating recent literature and anatomical considerations. This table integrates current literature findings and reflects the variability in clinical strategies depending on the anatomical site of the lesion.

| Localization | Preferred imaging | Surgical considerations | Medical therapy | Special notes |

| Brain/CNS | MRI | Craniotomy with cyst excision | Albendazole perioperatively | High risk of rupture; pre-op imaging critical |

| Bone/spine | CT/MRI | En bloc resection ± stabilization | Long-term albendazole | Often mimics tumors; recurrence risk high |

| Kidneys | CT/US | Partial/total nephrectomy | Albendazole + scolicidal agents | Differentiate from neoplasms |

| Thyroid/neck | MRI/US | Organ-preserving resection if feasible | Short course albendazole | Careful dissection to avoid dissemination. FNAB is also appropriate |

| Breast | US, MRI | Pericystectomy | Albendazole pre- and postoperatively | Rare; can mimic malignancy. Diagnosis requires high index of suspicion. |

| Retroperitoneum | CT/MRI | Surgical excision where accessible | Albendazole pre- and postoperatively | Risk of incomplete resection |

| Soft tissues/muscle | MRI | Complete cyst removal | Adjunctive therapy recommended | Often misdiagnosed as sarcoma or abscess |

| Pelvic organs | MRI | Organ-sparing surgery if possible | Albendazole + scolicidal agents | May mimic gynecologic tumors |

These findings reinforce the notion that successful management of echinococcosis in atypical locations relies on individualized diagnostic and therapeutic strategies, built upon a multidisciplinary foundation and informed by an evolving global literature.

In conclusion, the presented clinical review not only broadens our understanding of the potential manifestations of hydatid disease in rare localization but also reinforces the need for a systematic, multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis and treatment. It serves as a reminder that even rare localizations of parasitic diseases require clinical attention and integrated care strategies. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for echinococcosis even in rare anatomical sites, especially in endemic areas. Development of standardized diagnostic and therapeutic algorithms and reporting systems will be critical in improving outcomes for these complex cases.

| 1. | Brunetti E, Kern P, Vuitton DA; Writing Panel for the WHO-IWGE. Expert consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in humans. Acta Trop. 2010;114:1-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1638] [Cited by in RCA: 1414] [Article Influence: 88.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wen H, Vuitton L, Tuxun T, Li J, Vuitton DA, Zhang W, McManus DP. Echinococcosis: Advances in the 21st Century. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2019;32:e00075-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 421] [Cited by in RCA: 702] [Article Influence: 100.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Vuitton DA, McManus DP, Rogan MT, Romig T, Gottstein B, Naidich A, Tuxun T, Wen H, Menezes da Silva A; World Association of Echinococcosis. International consensus on terminology to be used in the field of echinococcoses. Parasite. 2020;27:41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 33.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Deplazes P, Rinaldi L, Alvarez Rojas CA, Torgerson PR, Harandi MF, Romig T, Antolova D, Schurer JM, Lahmar S, Cringoli G, Magambo J, Thompson RC, Jenkins EJ. Global Distribution of Alveolar and Cystic Echinococcosis. Adv Parasitol. 2017;95:315-493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 432] [Cited by in RCA: 685] [Article Influence: 76.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Shahriarirad R, Erfani A, Eskandarisani M, Rastegarian M, Sarkari B. Uncommon Locations of Cystic Echinococcosis: A Report of 46 Cases from Southern Iran. Surg Res Pract. 2020;2020:2061045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Alekya K, Meraj M, Moorthy NLN. Imaging features of hydatid cyst in unusual locations: A case series. Indian J Med Sci. 2024;0:1-4. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 7. | Bennane W, Moussahim A, Chakir Y, Soussi Abdallaoui M, Fadil A, Aboutaeib R. Multiple Disseminated Hydatidosis with Rare Locations: Mediastinal, Pancreatic and Pelvic (Case Report). Eur J Med Health Sci. 2024;6:20-22. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Gader G, Slimane A, Sliti F, Kherifech M, Belhaj A, Bouhoula A, Kallel J. Hydatid cyst of the brainstem: The rarest of the rare locations for echinococcosis. Radiol Case Rep. 2024;19:4422-4425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yordanov A, Boncev R, Kostov S, Kornovski Y, Ivanova Y, Slavchev S, Todorova V, Karakadieva K, Tranchev L, Vasileva-Slaveva M. A very rare case of echinococcus granulosus arising in the ovary and the uterus. Prz Menopauzalny. 2023;22:236-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Di Giambenedetto S, Fagotti A, Quaranta G, Iannone V, Fancello G, Steiner RJ, Mazzon G, Masucci L, Teodorico E, Borghetti A, Naldini A, Scambia G. Reporting a single case of cystic echinococcosis in retroperitoneal mass of uncertain origin. Parasitol Res. 2023;123:40. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Celik AS, Yosunkaya H, Yayilkan Ozyilmaz A, Memis KB, Aydin S. Echinococcus granulosus in atypical localizations: Five case reports. World J Nephrol. 2025;14:103027. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yuksel M, Demirpolat G, Sever A, Bakaris S, Bulbuloglu E, Elmas N. Hydatid disease involving some rare locations in the body: a pictorial essay. Korean J Radiol. 2007;8:531-540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Srinivas MR, Deepashri B, Lakshmeesha MT. Imaging Spectrum of Hydatid Disease: Usual and Unusual Locations. Pol J Radiol. 2016;81:190-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Aydin S, Tek C, Dilek Gokharman F, Fatihoglu E, Nercis Kosar P. Isolated hydatid cyst of thyroid: An unusual case. Ultrasound. 2018;26:251-253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Karmazanovsky GG, Stepanova YA, Kondratyev EV, Stashkiv VI. Hepatic echinococcosis: difficulties in diagnosis at the early stages of progression and with complications (literature review). Ann Hir Gepatol. 2021;26:18-23. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Aledavoud A, Mohammadi M, Ataei A, Shahesmaeilinejad A, Harandi MF. Thyroid involvement in cystic echinococcosis: a systematic review. BMC Infect Dis. 2024;24:889. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mutafchiyski VM, Popivanov GI, Tabakov MS, Vasilev VV, Kjossev KT, Cirocchi R, Philipov AT, Vaseva VS, Baitchev GT, Ribarov R, Konaktchieva MN. Cystic Echinococcosis of the Breast - Diagnostic Dilemma or just a Rare Primary Localization. Folia Med (Plovdiv). 2020;62:23-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kbir GH, Messaoudi S, Selmi M, Maatouk M, Bouzidi MT, Ennaceur F, Ben Moussa M. An unusual localization of echinococcosis: Gallbladder hydatid cyst. IDCases. 2022;27:e01455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Koppen T, Barth TFE, Eichhorn KW, Gabrielpillai J, Kader R, Bootz F, Send T. Alveolar Echinococcosis of the Parotid Gland-An Ultra Rare Location Reported from Western Europe. Pathogens. 2021;10:426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ramos Pascua L, Santos Sanchez JA, Samper Wamba JD, Alvarez Castro A, Rodriguez Altonaga J. Atypical image findings in a primary subcutaneous hydatid cyst in the gluteal area. Radiography (Lond). 2017;23:e65-e67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Chablou M, Id M'barek A, Chacha R, Merhom A, Tahi M. A Solitary Abscessed Hydatid Cyst of the Buttock: A Rare Case. Cureus. 2023;15:e38823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Mona C, Meryam M, Nizar K, Yazid B, Amara A, Haithem Z, Dhafer H, Anis BM. Exploring rare locations of hydatid disease: a retrospective case series. BMC Surg. 2024;24:160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | El Mahi N, Siouri H, Mojahid A, Haddar K, Ziani H, Nasri S, Kamaoui I, Skiker I. Femoral hydatid cyst: A rare localization of bone echinococcosis: A case report. Radiol Case Rep. 2025;20:1691-1694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yousofi Darani H, Jafari R. Renal echinococcosis; the parasite, host immune response, diagnosis and management. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2020;14:420-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Firouzi A, Neshati Pir Borj M, Alizadeh Ghavidel A. Cardiac hydatid cyst: A rare presentation of echinococcal infection. J Cardiovasc Thorac Res. 2019;11:75-77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Martinese G, Lucidi V, Masi PD, Adduci F, Cappelli A, Renzulli M, De Paolis M, Fiore M, Golfieri R. Bone echinococcosis with hip localization: A case report with evaluation of imaging features. Radiol Case Rep. 2022;17:3389-3394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Versaci A, Scuderi G, Rosato A, Angiò LG, Oliva G, Sfuncia G, Saladino E, Macrì A. Rare localizations of echinococcosis: personal experience. ANZ J Surg. 2005;75:986-991. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/