Published online May 25, 2023. doi: 10.5527/wjn.v12.i3.40

Peer-review started: January 11, 2023

First decision: February 2, 2023

Revised: February 22, 2023

Accepted: March 14, 2023

Article in press: March 14, 2023

Published online: May 25, 2023

Processing time: 121 Days and 16.2 Hours

Preemptive living donor kidney transplantation (PLDKT) is recommended as the optimal treatment for end-stage renal disease.

To assess the rate of PLDKT among patients who accessed KT in our center and review the status of PLDKT in Egypt.

We performed a retrospective review of the patients who accessed KT in our center from November 2015 to November 2022. In addition, the PLDKT status in Egypt was reviewed relative to the literature.

Of the 304 patients who accessed KT, 32 patients (10.5%) had preemptive access to KT (PAKT). The means of age and estimated glomerular filtration rate were 31.7 ± 13 years and 12.8 ± 3.5 mL/min/1.73 m2, respectively. Fifty-nine patients had KT, including 3 PLDKTs only (5.1% of total KTs and 9.4% of PAKT). Twenty-nine patients (90.6%) failed to receive PLDKT due to donor unavailability (25%), exclusion (28.6%), regression from donation (3.6%), and patient regression on starting dialysis (39.3%). In multivariate analysis, known primary kidney disease (P = 0.002), patient age (P = 0.031) and sex (P = 0.001) were independent predictors of achievement of KT in our center. However, PAKT was not significantly (P = 0.065) associated with the achievement of KT. Review of the literature revealed lower rates of PLDKT in Egypt than those in the literature.

Patient age, sex, and primary kidney disease are independent predictors of achieving living donor KT. Despite its non-significant effect, PAKT may enhance the low rates of PLDKT. The main causes of non-achievement of PLDKT were patient regression on starting regular dialysis and donor unavailability or exclusion.

Core Tip: Patients with preemptive access to kidney transplantation (PAKT) may have significant differences from those with conventional access to KT, warranting more evaluation. In this study, known primary kidney disease was an independent factor of achievement of living donor KT (LDKT). In addition, the older age and female sex were independent predictors of non-achievement of LDKT. However, unavailability, regression, and exclusion of LDs and patient regression on starting dialysis may prevent achievement of preemptive LDKT (PLDKT) in patients with PAKT. Despite its non-significant effect, PAKT may improve the low rates of PLDKT. The current literature review may refer to that PLDKT has comparable or variably better outcomes than the conventional LDKT. Hence, PLDKT is recommended as the first choice for each candidate patient. In Egypt, the rate of PLDKT is still lower than that of other countries, warranting implementation of effective strategies to promote PLDKT.

- Citation: Gadelkareem RA, Abdelgawad AM, Reda A, Azoz NM, Zarzour MA, Mohammed N, Hammouda HM, Khalil M. Preemptive living donor kidney transplantation: Access, fate, and review of the status in Egypt. World J Nephrol 2023; 12(3): 40-55

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-6124/full/v12/i3/40.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5527/wjn.v12.i3.40

Preemptive kidney transplantation (PKT) is defined as receiving kidney transplantation (KT) before initiation of maintenance dialysis in patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD)[1,2]. This definition may vary from one KT program to another, where patients who receive dialysis sessions sporadically or as conditioning pre-transplantation sessions for no more than 1 wk may be included in this definition[2-6]. The evolution of PKT was more than 30 years ago[7], when it passed through an insidious course and gained variably insufficient interests among the physicians and surgeons in the KT community[1,5]. Many initiatives and programs have been triggered to promote PKT, especially in the sector of living donor kidney transplantation (LDKT). These initiatives promote living kidney donation (LKD) programs as the most effective contributor to PKT[4-7]. PKT is a time-based KT strategy controlled by setting the timing of KT surgery at a point just before the start of regular dialysis as much as possible. This philosophy represents the natural course of management of most diseases. However, it has generated debate along the different axes of KT, such as the proposed lead-time bias effect on the outcomes of PKT[8]. The incidence of PKT has improved gradually from 2% in its early years to 6%-7% in the last years. Most cases come from LDKT programs, where it may reach up to 34% in some countries that adopt LDKT programs[6,9]. The latter percentage refers to the fundamental role of LD in the promotion of PKT strategy[10]. Preemptive access to KT (PAKT) and waitlisting are other effective contributors to PKT. Hence, they are fundamental issues in PKT literature[1,11]. However, they have mostly been ignored in research from Egypt, where only LDKT is performed in adults[9,12-14] and pediatrics[15-17].

We assessed the percentage of patients with PAKT and their fate regarding the receipt of preemptive LDKT (PLDKT).

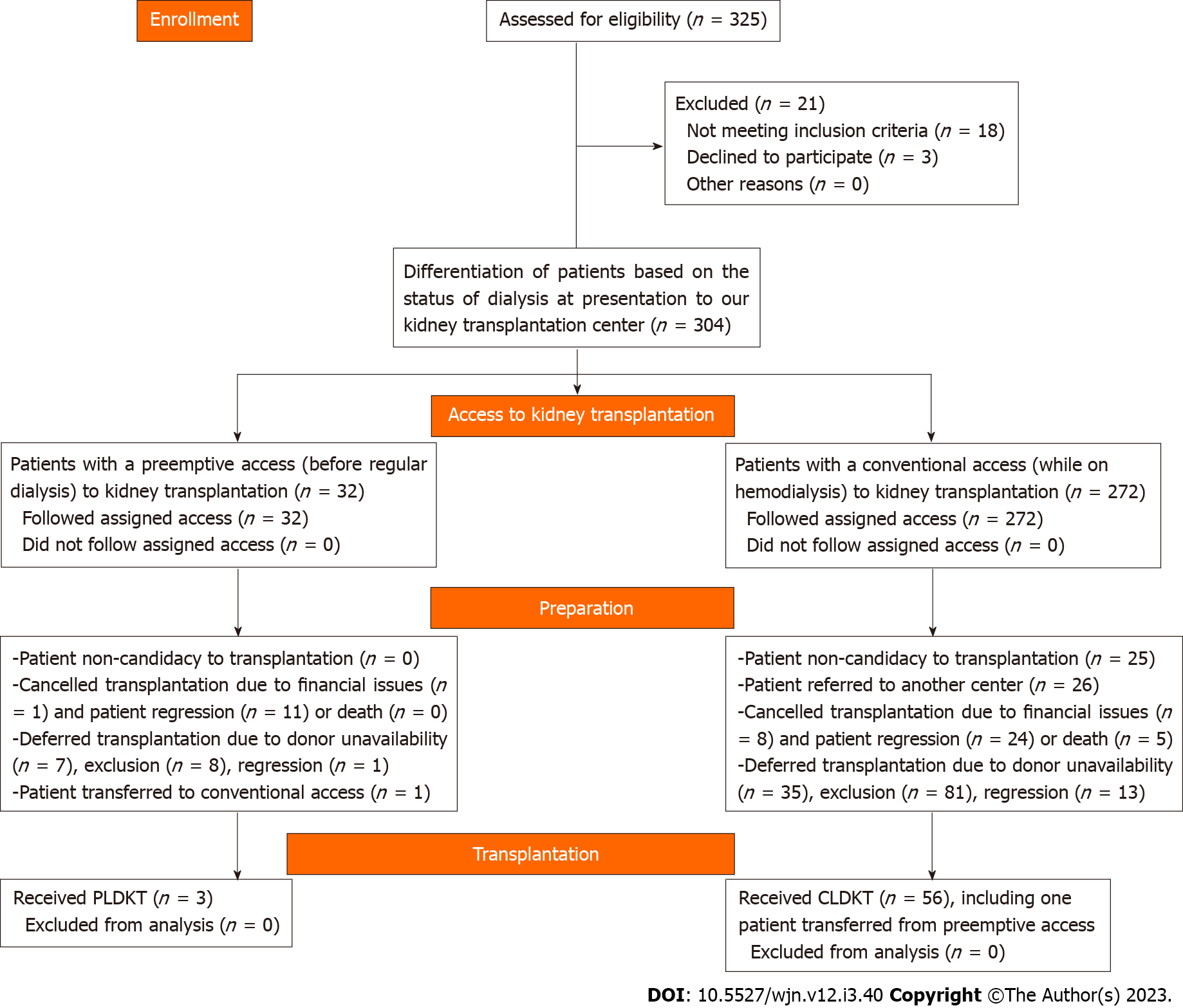

A retrospective review was performed for the electronic and manual records of patients with ESRD who sought LDKT in our center from November 2015 to November 2022. The study included both patients with PAKT, which was defined as the presentation of a patient with chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 4 or 5 for KT prior to the start of regular dialysis and those with conventional access to KT (CAKT). The exclusion criterion was patients who refused KT before starting the preparation for LDKT (Figure 1). The relevant demographic characteristics of the patients and potential donors including age, sex, and relatedness to the potential donors were reviewed. Also, the clinical data including the primary kidney disease, estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) at presentation, outcomes of preparation to KT, causes of deferring LDKT, and fate of the patients and donors were studied. We used the CKD-Epidemiology Collaboration creatinine equation to estimate eGFR for patients with PAKT[18].

Also, a review of the literature was performed to assess PLDKT in KT studies from Egypt. The KT center volume, pre-KT characteristics, and percentages and outcomes of PLDKT were reviewed. Furthermore, the literature was reviewed for the incidence of PLDKT in studies from other countries and large-volume KT registries.

This study was conducted as a topic in a KT research project regarding the outcomes of LDKT at our center. The institutional review board number is 17200148/2017.

Statistical analyses were performed with EasyMedStat (version 3.21.4; www.easymedstat.com). Continuous variables are presented as the mean ± standard deviation and range. However, categorical variables are presented as the number and percentage of each category. We created two groups (PAKT and CAKT) according to the status of dialysis at the time of access to transplantation. Normality and hetereoskedasticity of continuous data were assessed with the White test (or with Shapiro-Wilk in multivariate analysis) and Levene’s test, respectively. Continuous outcomes were compared with the unpaired Student t-test, Welch t-test, or Mann-Whitney U test according to the data distribution. Categorical outcomes were compared with the chi-squared or Fisher’s exact test accordingly. Multivariate logistic regression was performed to assess the factors contributing to achievement of KT in our center. Data were checked for multicollinearity with the Belsley-Kuh-Welsch technique. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Between November 2015 and November 2022, 325 patients attended our center for KT. Twenty-one (6.5%) patients changed their mind or were not serious in accessing KT. The remaining 304 patients were differentiated into PAKT and CAKT groups (Figure 1). The former group included 32 patients (10.5%) who were not on dialysis at the time of access to KT and the latter group included 272 (89.5%) patients with a mean (range) duration of hemodialysis of 6.3 ± 10.5 (0.5–108) mo. Both groups were compared for their demographic and clinical characteristics (Table 1). Follow-up after regression or exclusion decision varied from 3 mo to 6 years.

| Variables | PAKT, n = 32 | CAKT, n = 272 | P value |

| Age in yr, mean ± SD (range) | 31.7 ± 13 (13-60) | 32.1 ± 11.5 (12-66) | 0.677 |

| Sex | |||

| Men | 22 (68.8) | 213 (78.3) | 0.263 |

| Women | 10 (31.2) | 59 (21.7) | |

| Primary kidney disease | |||

| Glomerulonephritis | 3 (9.4) | 8 (2.9) | < 0.001 |

| Hereditary disease | 3 (9.4) | 6 (2.2) | |

| Obstructive uropathy | 4 (12.5) | 8 (2.9) | |

| Systemic disease | 4 (12.5) | 14 (5.2) | |

| Urolithiasis | 3 (9.4) | 7 (2.6) | |

| Unknown | 15 (46.9) | 229 (84.2) | |

| Number of potential donors1 | |||

| Patients presented without donors | 8 (25) | 36 (13.2) | 0.088 |

| With one donor | 17 (53.1) | 187 (68.8) | |

| With two donors | 4 (12.5) | 40 (14.7) | |

| With three donors | 3 (9.4) | 9 (3.3) | |

| Donor evaluation | 24 | 236 | |

| Patients with evaluated donors | 20 | 194 | |

| With accepted donor(s) | 10 (50) | 89 (45.9) | 0.232 |

| With one donor excluded | 7 (35) | 75 (38.7) | |

| With two donors excluded | 0 (0) | 15 (7.7) | |

| With three donors excluded | 1 (5) | 2 (1) | |

| With excluded and accepted donors | 2 (10) | 13 (6.7) | |

| Number of not evaluated donors per patient | 6 | 56 | |

| One donor | 3 (50) | 51 (91.1) | 0.024 |

| Two donors | 3 (50) | 4 (7.1) | |

| Three donors | 0 (0) | 1 (1.8) | |

| Order of the accepted donor | 12 | 102 | |

| First | 10 (83.3) | 87 (85.3) | 0.634 |

| Second | 1 (8.3) | 11 (10.8) | |

| Third | 1 (8.3) | 4 (3.9) | |

| Accepted donor age (yr), mean ± SD (range) | 38.1 ± 9 (25-53) | 40.6 ± 10.4 (21-60) | 0.39 |

| Patient-donor relatedness degree | |||

| First | 5 (41.7) | 55 (53.9) | 0.234 |

| Second | 5 (41.7) | 40 (39.2) | |

| Third | 1 (8.3) | 6 (5.9) | |

| Unrelated | 1 (8.3) | 1 (1) | |

| Sex of accepted donors | |||

| Women | 7 (58.3) | 66 (64.7) | 0.754 |

| Men | 5 (41.7) | 36 (35.3) | |

| Accepted donor commitment | |||

| Donated | 4 (33.3) | 55 (53.9) | 0.171 |

| Regressed | 1 (8.3) | 16 (15.7) | |

| Released | 7 (58.3) | 31 (30.4) | |

| Number of excluded donors per patient | |||

| One donor | 7 (77.8) | 84 (80) | 0.262 |

| Two donors | 1 (11.1) | 19 (18.1) | |

| Three donors | 1 (11.1) | 2 (1.9) | |

| Main causes of donor exclusion | |||

| Medical causes | 1 (10) | 51 (51.5) | 0.027 |

| Immunologic mismatch | 7 (70) | 34 (34.3) | |

| Combined medical and immunologic | 2 (20) | 14 (14.1) | |

| Main causes of donor release | 5 | 28 | |

| Financial causes | 0 (0) | 3 (10.7) | 0.235 |

| Patient death | 0 (0) | 3 (10.7) | |

| Patient non-candidacy | 0 (0) | 10 (35.7) | |

| Patient regression | 5 (100) | 12 (42.9) | |

| Achievement of kidney transplantation | |||

| Failed | 25 (78.1) | 191 (70.2) | 0.568 |

| Transplanted in our center | 4 (12.5) | 55 (20.2) | |

| Transplanted in another center | 3 (9.4) | 26 (9.6) | |

| Cause of non-achievement of transplantation in our center | 28 | 191 | |

| Donor exclusion | 8 (28.6) | 88 (40.6) | 0.035 |

| Donor regression | 1 (3.6) | 16 (7.4) | |

| Donor unavailability | 7 (25) | 37 (17.1) | |

| Financial causes | 1 (3.6) | 13 (5.6) | |

| Patient non-candidacy | 0 (0) | 25 (11.5) | |

| Patient death | 0 (0) | 5 (2.6) | |

| Patient regression | 11 (39.3) | 33 (15.2) | |

| Fate of recipients who failed to have transplantation in our center | |||

| Death | 0 (0) | 13 (6) | 0.213 |

| On hemodialysis | 24 (85.7) | 147 (67.7) | |

| Transplantation in another center | 3 (10.7) | 26 (12) | |

| Unknown | 1 (3.6) | 31 (14.3) | |

In the PAKT group, 29 patients (90.6%) failed to receive PLDKT due to original donor unavailability (25%), exclusion (28.6%), regression (3.6%), financial causes (3.6%), and patients’ regression from KT when starting regular dialysis (39.3%) (Table 1). Hence, PLDKT was carried out in 3 patients only, representing 5.1% of the total KTs and 9.4% of patients with PAKT. One of these three patients died from complications of the coronavirus disease 2019, 6 mo after KT. The other 2 patients were still living with a functioning graft for 68 and 12 mo at the time of writing of this article. The detailed characteristics of patients with PAKT are presented as individual patients (Table 2). The mean (range) age was 31.7 ± 13 (13-60) years. Most of the patients presented with stage 5 CKD. The mean (range) for serum creatinine level and eGFR was 6 ± 1.6 (3.2–9.8) mg/dL and 12.8 ± 4.8 (7–28) mL/min/1.73 m2, respectively.

| Case Number | Age in yr | Sex | No. of Potential donors relatedness | Primary kidney disease | Serum creatinine in mg/dL | Stage of CKD, eGFR as mL/min/ 1.73 m2 | PLDKT receipt | Cause of cancelled PLDKT | Fate of the patient |

| Case 1 | 48 | Male | 3 (Wife, Sister, daughter) | Unknown | 8.5 | 5 (7) | None | Donor exclusion | On HD for 20 m then CLDKT in our center |

| Case 2 | 25 | Male | 1 (Mother) | CMU | 5.5 | 5 (14) | None | Donor exclusion | On HD for 62 m |

| Case 3 | 28 | Male | 3 (Brothers) | Unknown | 8.2 | 5 (8) | None | Patient regression | On HD for 74 m |

| Case 4 | 59 | Female | 2 (Sons) | Diabetic nephropathy | 5.4 | 5 (11) | None | Patient regression | On HD 75 m |

| Case 5 | 47 | Male | 2 (Unrelated) | ADPCKD | 4.8 | 5 (14) | Yes | NA | Living with a functioning graft for 68 m |

| Case 6 | 26 | Male | 1 (Brother) | Urolithiasis | 7.8 | 5 (9) | None | Patient regression | On HD then lost to follow up |

| Case 7 | 27 | Male | 1 (Aunt) | Unknown | 6.9 | 5 (10) | None | Patient regression | On HD then CLDKT in another center |

| Case 8 | 38 | Male | 1 (Unrelated) | ADPCKD | 7.4 | 5 (9) | None | Donor exclusion | On HD for 34 m |

| Case 9 | 22 | Female | None | Unknown | 4.8 | 5 (12) | None | Donor unavailability | On HD for 33 m |

| Case 10 | 19 | Female | None | Unknown | 3.5 | 4 (19) | None | Donor unavailability | On HD for 24 m |

| Case 11 | 24 | Male | None | GN | 4.4 | 4 (18) | None | Donor unavailability | On HD then lost to follow-up |

| Case 12 | 13 | Male | 1 (Mother) | Congenital VURD | 4.6 | 4 (18) | Yes | NA | Died from COVID-19 complications |

| Case 13 | 14 | Male | 1 (Mother) | PUV | 5.3 | 4 (16) | None | Donor exclusion | On HD then CLDKT in another center |

| Case 14 | 23 | Male | 1 (Mother) | Urolithiasis | 5.1 | 5 (15) | None | Patient regression | On HD for 18 m |

| Case 15 | 34 | Female | 1 (Sister) | Unknown | 8.6 | 5 (8) | None | Donor regression | On HD for 6 m before death |

| Case 16 | 52 | Male | 1 (Brother) | ADPCKD | 6.2 | 5 (10) | None | Donor exclusion | On HD for 28 m |

| Case 17 | 19 | Male | None | VURD | 3.2 | 4 (28) | None | Donor unavailability | On HD 24 m |

| Case 18 | 36 | Male | 1 (Sister) | Hypertensive nephropathy | 6.8 | 5 (10) | None | Patient regression | On HD for 26 m |

| Case 19 | 34 | Male | 3 (Unrelated) | ADPCKD | 7.5 | 5 (9) | None | Donor exclusion | On HD for 27 m |

| Case 20 | 34 | Male | 2 (Brother, Sister) | Diabetic nephropathy | 8.4 | 5 (8) | None | Patient regression | On HD for 28 m |

| Case 21 | 15 | Male | 1 (Mother) | Unknown | 5.4 | 5 (15) | None | Donor exclusion | On HD for 6 m then lost to follow-up |

| Case 22 | 44 | Male | 1 (Brother) | Urolithiasis | 6.7 | 5 (10) | None | Patient regression | On HD for 8 m then lost to follow-up |

| Case 23 | 40 | Female | 1 (Cousin) | Unknown | 6.7 | 5 (7) | None | Donor regression | Unknown |

| Case 24 | 44 | Male | 1 (Brother) | Hyperuricemia | 5.6 | 5 (12) | None | Donor exclusion | On HD for 13 m |

| Case 25 | 19 | Male | 1 (Mother) | Congenital VURD | 4.7 | 4 (17) | Yes | NA | Living with a functioning graft for 12 m |

| Case 26 | 23 | Female | 1 (Mother) | Unknown | 6.3 | 5 (12) | None | Patient regression | On HD for 18 m |

| Case 27 | 60 | Male | None | Unknown | 5.6 | 5 (11) | None | Donor unavailability | On HD then CLDKT in another center |

| Case 28 | 29 | Male | 1 (Sister) | GN | 3.9 | 4 (19) | None | Donor exclusion | On HD 8 m |

| Case 29 | 25 | Female | 1 (Brother) | Unknown | 9.8 | 5 (7) | None | Patient regression | On HD for 6 m |

| Case 30 | 47 | Female | None | Unknown | 6.4 | 5 (12) | None | Patient regression | On HD for 16 m |

| Case 31 | 25 | Male | None | FSGS | 4.5 | 4 (18) | None | Donor unavailability | On HD for 5 m |

| Case 32 | 21 | Female | None | Unknown | 4.2 | 4 (18) | None | Donor unavailability | On HD for 3 m |

In the current cohort of patients, the total number of patients who had been transplanted at our center (59 patients) or at other centers (29 patients) was 88 (28.9%) patients. In a comparison between the patients who achieved (59 patients) and those who failed to achieve (245 patients) LDKT in our center, there were significant differences in age (P = 0.034), sex (P < 0.001), primary kidney disease (P = 0.008), number of potential donors (P = 0.003), and acceptance/exclusion rate of evaluated donors (P < 0.001) per patient (Table 3).

| Variables | Achievement, n = 59 | Non-achievement, n = 245 | P value | |

| Age in yr, mean ± SD (range) | 29 ± 9.9 (13-57) | 32.8 ± 11.9 (12-66) | 0.034 | |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 56 (94.9) | 179 (73.1) | < 0.001 | |

| Female | 3 (5.1) | 66 (26.9) | ||

| Dialysis status | ||||

| Preemptive access | 4 (6.8) | 28 (11.4) | 0.354 | |

| On regular dialysis | 55 (93.2 | 217 (88.6) | ||

| Primary kidney disease | ||||

| Unknown causes | 41 (69.5) | 202 (82.4) | 0.008 | |

| Systemic diseases | 3 (5.1) | 18 (7.4) | ||

| Renal diseases | 15 (25.4) | 25 (10.2) | ||

| Number of potential donors per patient1 | ||||

| Donor unavailability | 0 (0) | 44 (18) | 0.003 | |

| One donor | 43 (72.9) | 161 (65.7) | ||

| Two donors | 13 (22) | 31 (12.6) | ||

| Three donors | 3 (5.1) | 9 (3.7) | ||

| Outcome of donor evaluation1 | ||||

| Accepted | 48 (81.4) | 51 (32.9) | < 0.001 | |

| Excluded | 0 (0) | 100 (64.5) | ||

| Excluded and accepted | 11 (18.6) | 4 (2.6) | ||

| Number of not-evaluated donors per patient1 | ||||

| One donor | 4 (100) | 51 (86.4) | > 0.999 | |

| Two donors | 0 (0) | 7 (11.9) | ||

| Three donors | 0 (0) | 1 (1.7) | ||

| Chronological order of accepted donor1 | n = 59 | n = 55 | ||

| First | 48 (81.4) | 49 (89.1) | 0.596 | |

| Second | 8 (13.6) | 4 (7.3) | ||

| Third | 3 (5.1) | 2 (3.6) | ||

| Age of accepted donors, mean ± SD (range) | 40.2 ± 10.9 (21-60) | 40.5 ± 9.5 (26-58) | 0.937 | |

| Degree of relatedness of accepted donors1 | ||||

| First | 34 (57.6) | 26 (47.3) | 0.339 | |

| Second | 20 (33.9) | 25 (45.4) | ||

| Third | 3 (5.1) | 4 (7.3) | ||

| Unrelated | 2 (3.4) | 0 (0) | ||

| Sex of accepted donor1 | ||||

| Male | 20 (33.9) | 21 (38.2) | 0.779 | |

| Female | 39 (66.1) | 34 (61.8) | ||

| Number of excluded donors per patient1 | n = 11 | n = 102 | ||

| One donor | 8 (72.7) | 82 (80.4) | 0.572 | |

| Two donors | 3 (27.3) | 17 (16.7) | ||

| Three donors | 0 (0) | 3 (2.9) | ||

| Main causes of donor exclusion1 | n = 9 | n = 100 | ||

| Medical causes | 5 (55.6) | 47 (47) | 0.462 | |

| Immunologic mismatches | 2 (22.2) | 39 (39) | ||

| Combined medical and immunologic causes | 2 (22.2) | 14 (14) | ||

In multivariate analysis, known primary kidney disease (P = 0.002) was associated with higher rates of achievement of KT in our center. In addition, female sex (P = 0.001) and older patients (P = 0.031) were significantly associated with lower rates of achievement of KT in our center. However, PAKT (P = 0.065) and multiple potential donors (P = 0.529) were not significantly associated with the rate of achievement of KT in our center (Table 4).

| Variables | Modality | Odds ratio | P value |

| Age | Younger vs older | 0.97 (0.94-0.997) | 0.031 |

| Sex | Men vs women | 0.14 (0.04-0.46) | 0.001 |

| Dialysis status | Preemptive vs on dialysis | 0.31 (0.09-1.1) | 0.065 |

| Primary kidney disease | Known vs unknown | 3.24 (1.5-6.9) | 0.002 |

| Number of potential donors | One vs multiple | 0.81 (0.42–1.57) | 0.529 |

Review of the literature for PLDKT in studies from Egypt revealed that only eight articles addressed PLDKT (Table 5). These articles were from three academic centers only, including seven original research and one opinion article. The percentage of PLDKT varied between 6.4% in adults and 23% in pediatrics. No articles addressed the PAKT or waitlisting. The reported patient and graft survival rates were similar to those of conventional LDKT (CLDKT) in the literature.

| Ref. | Publishing place | Settings | Type | Aim | Scope relative to PLDKT | Target age group | Outcomes relative to ELDKT/ CLDKT | Number of patients; PLDKT/Total (Percentage of PLDKT) |

| El-Agroudy et al[12] | Transplantation | Mansoura University | Retrospective comparative | Compare outcomes of CLDKT & PLDKT | Specific | Mixed | Comparable, except in death with functioning graft was due to CVD in PLDKT vs respiratory infections in CLDKT | 82/1279 (6.4%) |

| Bakr and Ghoneim[14] | Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl | Mansoura University | Retrospective series | Present experience in KT | General | Mixed | Overall graft survival rates were 76% and 52% at five and 10-yr, respectively | 82/1690 (4.9%) |

| El-Husseini et al[15] | Pediatr Nephrol | Mansoura University | Retrospective series | Evaluate outcomes of pediatric LDKT | General | Pediatrics | 5-yr graft survival was 73.6% | 51/216 (23%) |

| Mosaad et al[16] | Dial Transpl | Mansoura University | Retrospective series | Study LDKT survival in low-weight children | General | Pediatrics | PLDKT might provide better graft survival | 9/63 (14.3%) |

| Saadi et al[13] | Egyptian J Int Med | Cairo University | Retrospective series | Identify KT Epidemiology in Cairo University hospitals | General | Mixed | Most of patients and donors were males, mostly as LDKT | 14/282 (5%) |

| 1Gadelkareem et al[9] | Afr J Urol | Assiut University | Prospective comparative | Compare short term outcomes of ELDKT & PLDKT | Specific | Adults | Comparable, except AR higher in ELDKT; Lymphocele incidence was higher in PLDKT | PLDKT 30/45; ELDKT 15/45 |

| Gadelkareem et al[8] | Exp Tech Urol Nephrol | Assiut University | Opinion | Suppose that lead time should not be a bias effect in PKT | Specific | Mixed | Lead time is a mere character of PKT rather than a bias | NA |

| Fadel et al[17] | Pediatr Transpl | Cairo University | Retrospective series | Present experience in pediatric KT | General | Pediatrics | Timely referral and parent education were recommended | PLDKT 11/148 (7%); ELDKT 59/148 (40%) |

| Index study | World J Nephrol | Assiut University | Retrospective series | Present experience | Specific | Mixed | Urological causes are main contributor | PLDKT 3/59 (5.1%) |

In addition, a review of the English literature for the incidence of PLDKT in other countries revealed higher rates than those from Egypt. However, they reported on PKT from both LDs and deceased donors. There were higher rates of PKT in patients who received LDKT than in those who received deceased donor KT (Table 6). In 1987, Migliori et al[19] were the first to evaluate the effects and outcomes of PKT in a large study from the United States, reporting a PKT rate of 7.6%. They were followed by two European studies with variable rates[20,21]. Then, five studies presented data from registries from United States and Canada and reported higher PKT rates up to 21% of the total KTs and more than 29% of LDKTs[22-26]. In addition, three studies from Japan, Australia, and Korea presented PLDKT rates up to 22% in patients receiving LDKT[27-29]. In 2009, two studies of mixed LD and deceased donor KTs showed higher rates of PLDKT about 39%[30,31]. Between 2011 and 2016, five studies of pediatric and adult KT showed similar rates[2,32-35]. In the last 3 years, many studies have reported high PLDKT rates more than 34%of LDKTs[36-38].

| Ref. | Countryand/or Registry | Total KT Number | PKT | LDKT number (Percentage of PLDKT) | PKT per donor type | |

| LD | DD | |||||

| Migliori et al[19] | United States | 1742 | 132 (7.6%) | 1056 (9.1) | 96 (73) | 36 (27) |

| Berthoux et al[20] | ERA-EDTA | 35348 | 2545 (7.2) | 1097 (73.3) | 804 (31.6) | 1741 (68.4) |

| Asderakis et al[21] | United Kingdom | 1463 | 161 (11) | 118 (19.5) | 23 (14) | 138 (86) |

| Papalois et al[22] | United States | 1849 | 385 (20.8) | 1074 (29.1) | 313 (81.3) | 72 (18.7) |

| 1Mange et al[23] | United States; USRDS | 8489 | 1819 (21.4) | 1819 (21.4) | 1819 (100) | NA |

| Kasiske et al[24] | United States; UNOS | 38836 | 5126 (13.2) | 13078 (24) | 3145 (61.4) | 1981 (38.6) |

| Gill et al[25] | Canada; CORR | 40963 | 5996 (14.6) | 11290 (26.6) | 2999 (50.5) | 2967 (49.5) |

| Ashby et al[26] | United States; OPTN/SRTR | 102331 | 17885 (17.5) | 44033 (26.3) | 11601 (65) | 6284 (35) |

| 1Ishikawa et al[27] | Japan; JRTR | 834 | 112 (13.4) | 834 (13.4) | 112 (100) | NA |

| 1Milton et al[28] | ANZDATA | 2603 | 578 (22) | 578 (22) | 578 (100) | NA |

| 1Yoo et al[29] | Korea | 499 | 81 (16.2) | 499 (16.2) | 81 (100) | NA |

| Gore et al[30] | United States; UNOS | 41090 | 11026 (26.8) | 15940 (39.4) | 6282 (57) | 4744 (43) |

| Witczak et al[31] | Norway | 3400 | 809 (24) | 1415 (36.3) | 514 (64) | 295 (36) |

| 2Kramer et al[32] | ERA-EDTA | 1829 | 444 (21.2) | 1073 (11.5) | 123 (72) | 321 (28) |

| Grams et al[33] | United States; UNOS | 152731 | 19471 (12.8) | NA | 11554 (59) | 7917 (41) |

| 1Grace et al[34] | ANZDATA | 4105 | 660 (16.1) | 2058 (16.1) | 660 (100) | NA |

| 2Patzer et al[35] | United States; USRDS | 5774 | 1117 (19.3) | 2598 (28.8) | 747 (67) | 370 (33) |

| Jay et al[2] | United States; UNOS | 141254 | 24609 (17) | 46373 (31) | 14503 (59) | 10106 (41) |

| Prezelin-Reydit et al[36] | France; REIN | 22345 | 3112 (14) | 2031 (34) | 690 (22.2) | 2422 (77.8) |

| 1Kim et al[37] | South Korea | 1984 | 429 (21.6) | 1984 (21.6) | 429 (100) | NA |

| 2Prezelin-Reydit et al[38] | France; REIN | 1911 | 380 (19.8) | 240 (37.5) | 90 (23.7) | 290 (76.3) |

We addressed the topic of PKT in Egypt, because there is a question that whether the reported incidence of PLDKT correlates with the international values. Because this question may entail addressing the barriers and the promoting strategies of PLDKT, we performed this retrospective study to assess the outcomes of patients accessed KT at our center. In addition, review of PLDKT publications coming from Egypt was carried out in the context of the international literature, either as specific studies for PLDKT within LDKT cohorts or as combined LDKT and deceased donor KT researches. There is significant variability in the rates of PKT all over the world. In most studies, the proportions of PLDKT are higher than those of PKT in deceased donor KT. Most of these studies showed significantly higher incidences in adults and pediatrics. However, because the total percentages of LDKT are lower than those of KT from deceased donors, the frequency of PKT from deceased donors represented the majority of cases of PKT in some studies. However, relative to the total numbers of donor source, the percentages of PLDKT of total LDKTs are steadily higher than those of PKT from the total deceased donor KTs (Table 6).

In Egypt, there is an obvious lack of research on PKT represented by the small number of studies that was found in this topic[12-16]. These studies were mostly retrospective and presented as few centers’ experiences or small cohorts of patients. Hence, the volume of research on PLDKT is relatively small, referring to that PKT does not seem to be in the focus of research. PLDKT has just been mentioned as a category within the total cohorts of KT from centers with well-established KT programs[13,17]. On the other hand, a few studies were specifically conducted to study PLDKT outcomes in comparison to CLDKT[9,12]. This may be a part of the lack in the international literature, which has a slowly propagating body of research on PKT[33,38]. Currently, the literature refers to some sort of practical negligence of PKT in many forms, including disparities in access to PKT among the waitlisted patients. In a study from the United States, relative to the rates of White (38%) and Black (31%) patients on the waiting list, there was a significant difference between the rates of White (65%) and Black (17%) patients who had PKT in 2019[1]. Also, there is a substantially lower rates of PAKT among certain demographic groups that may face challenges in engaging with complex health care systems. Patients with low levels of education and those with physician-dependent choice of KT are other groups with disparities in the access to PKT. Inequities in access to KT require substantial efforts and multiple remedies[1]. Unfortunately, there is no studies have been conducted in Egypt to measure the rates of access to PLDKT so far. The current study showed that PAKT represented only 10.5% of patients who were referred to KT in our center.

From the reviewed literature, the reported incidence of PLDKT in the different Egyptian KT centers was relatively lower than the international values (Tables 5 and 6). The range was 5%-6% of the total KTs that were performed in these centers[12,13]. However, the incidence was higher, when PLDKT was studied in a certain category of population, such as pediatrics with low-body weight[16,17]. Similarly, the rate of PLDKT was 5.1% in the current study. However, these values are still significantly lower than the values reported in the international literature (Table 6).

Patients with PAKT may have high education levels, payment resources, married status, residence near to KT centers, and younger age than those with CAKT. Unknown primary diseases and glomerulonephritis seemed to be the most common categories of primary kidney disease in adults[9,12,21]. Among pediatrics, reflux nephropathies, nephrotic syndromes, and congenital anomalies are the commonest primary diseases[15,16]. In addition, PLDKT patients had a lower likelihood of testing positive for hepatic viruses and receiving a blood transfusion than the CLDKT patients[12]. Of the 304 patients who accessed LDKT in our center, only 32 patients had PAKT. In turn, only 3 patients succeeded in having PLDKT and they included 2 children and 1 adult patient. They had congenital or hereditary diseases as primary causes of ESRD and the donors were unrelated donor in one case and mothers in the other 2 cases.

A large retrospective study from Mansoura Urology and Nephrology Center studied the course and outcomes of PLDKT and reported an incidence of 6.4%. In addition, it showed that there was only a significant difference in the percentages of patients who died with functioning grafts due to cardiovascular disorders and respiratory infections. The former cause was higher in PLDKT, while the latter was higher in CLDKT[12]. In a smaller prospective comparative study, we found that the incidence of acute graft rejection was significantly higher among early LDKT (ELDKT) patients than in PLDKT patients. However, the incidence of lymphoceles was significantly higher in PLDKT patients than in patients receiving ELDKT[9]. In the current study, the rates of non-candidacy and death during preparation to KT were lower in patients with PAKT (0%) than in patients with CAKT (10.7% and 35.7%, respectively). These rates may be because patients in the former group were healthier than those in the latter group.

The previous characteristic may be a surrogate of the concerns raised about the proposed effect of the lead-time bias on the advantaged outcomes of PLDKT. However, there may be a different perspective, regarding this postulation. We hypothesized that the proposed effects are a mere component of the strategy of PKT. This could simply be explained by considering the PKT and non-PKT as consecutive rather than parallel processes along the course of ESRD. PKT is an early step in the management of ESRD. So, the time factor should be considered a promotor rather than a confounder to PKT process. On the other hand, the idea of removal of the lead-time bias means discarding the spirit of the entire process of PKT[8]. The best support of this perspective is studying the outcomes of KT relative to the time-point at which KT is performed. Goldfarb-Rumyantzev et al[39] designed a study based on this idea and it revealed significant survival advantages when KT was performed before 180 d of dialysis.

Internationally, many articles have addressed the barriers of PKT. The unavailability of a suitable, willing donor is a major confounder to PLDKT[40-42]. In accordance, the current results revealed that younger age, male sex, and known primary kidney disease of patients accessing KT in our center were independent predictors of achievement of KT after preparation. However, the dialysis status (PAKT vs CAKT), number of potential donors, and their acceptance/exclusion rates were not significantly associated with the achievement of KT. The non-significant effect of PAKT may be attributed to the delayed access of the patients with ESRD. Most of our patients with PAKT were in stage 5 CKD and a mean eGFR of 12.8 ± 4.8 mL/min/1.73 m2, when they first presented to our clinic. This value of eGFR is comparable to the reported values that allow successful PLDKT[33,43], but these patients were not prepared or waitlisted before presentation to the KT unit. Hence, they needed long duration for preparation, which might be, with donor exclusion, the causes of missing the chance of PLDKT. In addition, the delayed access might be attributed to absence of a well-configured waitlisting programs in our country to refer and prepare patients at the suitable stages of ESRD. On the other hand, there are many underlying primary renal diseases that may predispose to a very late presentation of a significant proportion of patients, such as the status of pending dialysis at first discovery of their ESRD[44].

Problems of unavailability of a well-integrated healthcare system that facilitates early detection of CKD patients and timely referral to KT centers should be practically considered. Paradoxically and despite the observable social fear of ESRD, which may progress up to a disease phobia in developing countries[45], there are many patient-related factors that influence early diagnosis and management of CKD patients such as the cultural and health illiteracies[44]. As a developing country, the healthcare authorities in Egypt have a large burden of challenges which seem hard to be overcome due to factors such as low per-capita income and slowly progressing corrections of the healthcare systems[15]. Also, the ethical problems that have been raised about KT practice in Egypt represent another major confounder to correction[46]. However, the recent policies in the Egyptian national healthcare system seem to be promising as a mass modification to overcome these problems, including the new national health insurance coverage and national KT programs.

The limitations of the current study included the small number of patients who had PLDKT, which made us unable to perform statistical analyses for the independent factors of failure of most patients with PAKT to achieve PLDKT. However, this is the first study from Egypt to address this very viable topic at a national review basis. Hence, it may unmask the vague situation of PLDKT in Egypt by configuring a step forward in building more integrated KT systems.

Based on relevant literature review, we may recommend implementation of different strategies to promote PLDKT in Egypt. Encouragement of LKD is the main strategy that should be extensively studied, because our national KT program is currently devoted to LDKT only. Minimally-invasive approaches such as laparoscopic living donor nephrectomy should be introduced to all centers of KT. Also, the regulations of LKD should be organized under a well-configured national donation program, including donor exchange programs. Furthermore, promotion of healthcare facilities of early detection of CKD and education of the contributors of PLDKT process are crucial strategies for this topic. The latter includes the education of the physicians (representing the moderator of the process), ESRD patients (representing the key start of the process), and publics (representing the source of the potential donors) about the benefits of PKT.

Patients with PAKT may have significant differences from those with CAKT regarding age, sex, primary kidney disease, and number of potential donors at presentation to a KT center. A primary kidney disease diagnosis is an independent factor of achievement of LDKT. In addition, older age and female sex are independent predictors of non-achievement of LDKT. On the other hand, unavailability, regression, and exclusion of LDs and patient regression when reach dialysis may hinder the achievement of PLDKT in patients with PAKT. Despite its non-significant effect, PAKT may improve the low rates of PLDKT. The current literature review may refer to that PLDKT has comparable or slightly better outcomes than those of CLDKT. Hence, PLDKT is recommended as the first choice for each candidate patient. In Egypt, PLDKT may have similar barriers to those presented elsewhere in the literature, including the shortage of donors, delayed presentation of patients and socioeconomic factors. As a result, the rate of PLDKT is still low in Egypt, warranting implementation of many strategies to promote PLDKT. They include encouraging LKD, introduction of minimally-invasive living donor nephrectomy, configuring a specific program for LKD, and education of the physicians, patients and publics about the benefits of PKT.

Despite its low rates, preemptive living donor kidney transplantation (PLDKT) is recommended as the optimal treatment for end-stage renal disease. However, its rate is still lower than the expected rates worldwide.

Promotion of the rate of PLDKT seems to be a modifiable variable for improvement of the total outcomes of KT.

To assess the rate of achievement of PLDKT among patients accessing KT in our center and to review the status of PLDKT in Egypt in the context of the international literature.

We performed a retrospective review of the records of patients who accessed KT in our center from November 2015 to November 2022. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients and their potential donors were reviewed. Also, the literature was reviewed for PLDKT status in Egypt.

Of 304 patients accessed KT, 32 patients (10.5%) had preemptive access to KT (PAKT). The means of age and estimated glomerular filtration rate were 31.7 ± 13 years and 12.8 ± 3.5 mL/min/1.73 m2, respectively. Fifty-nine patients had KT, including three PLDKTs only (5.1% of the total KTs and 9.4% of PAKT). Twenty-nine patients (90.6%) failed to receive PLDKT due to donor unavailability (25%), exclusion (28.6%), regression from donation (3.6%), and patient regression on starting dialysis (39.3%). In multivariate analysis, known primary kidney disease (P = 0.002), patient age (P = 0.031) and sex (P = 0.001) were independent predictors of achievement of KT in our center. However, PAKT was not significantly (P = 0.065) associated with the achievement of KT. Review of the literature revealed lower rates of PLDKT in Egypt, including the current results, than the internationally reported rates.

Patient age, sex, and primary kidney disease are independent predictors of achieving LDKT. Despite its non-significant effect, PAKT may improve the low rates of PLDKT. The main causes of non-achievement of PLDKT were patient regression on starting regular dialysis and donor unavailability or exclusion.

Studying the factors that may promote the early access of ESRD patients to KT may improve the rates of PLDKT. This latter strategy may improve the whole outcomes of the process of KT, including avoidance of the inconveniences of dialysis and improvement of the graft and patient survival rates.

| 1. | Reese PP, Mohan S, King KL, Williams WW, Potluri VS, Harhay MN, Eneanya ND. Racial disparities in preemptive waitlisting and deceased donor kidney transplantation: Ethics and solutions. Am J Transplant. 2021;21:958-967. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Jay CL, Dean PG, Helmick RA, Stegall MD. Reassessing Preemptive Kidney Transplantation in the United States: Are We Making Progress? Transplantation. 2016;100:1120-1127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Chopra B, Sureshkumar KK. Kidney transplantation in older recipients: Preemptive high KDPI kidney vs lower KDPI kidney after varying dialysis vintage. World J Transplant. 2018;8:102-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Helmick RA, Jay CL, Price BA, Dean PG, Stegall MD. Identifying Barriers to Preemptive Kidney Transplantation in a Living Donor Transplant Cohort. Transplant Direct. 2018;4:e356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Abramowicz D, Hazzan M, Maggiore U, Peruzzi L, Cochat P, Oberbauer R, Haller MC, Van Biesen W; Descartes Working Group and the European Renal Best Practice (ERBP) Advisory Board. Does pre-emptive transplantation vs post start of dialysis transplantation with a kidney from a living donor improve outcomes after transplantation? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31:691-697. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Friedewald JJ, Reese PP. The kidney-first initiative: what is the current status of preemptive transplantation? Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2012;19:252-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Abecassis M, Bartlett ST, Collins AJ, Davis CL, Delmonico FL, Friedewald JJ, Hays R, Howard A, Jones E, Leichtman AB, Merion RM, Metzger RA, Pradel F, Schweitzer EJ, Velez RL, Gaston RS. Kidney transplantation as primary therapy for end-stage renal disease: a National Kidney Foundation/Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (NKF/KDOQITM) conference. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;3:471-480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 404] [Cited by in RCA: 445] [Article Influence: 24.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gadelkareem RA, Zarzour MA, Khalil M, Azoz NM, Reda A, Abdelgawad AM, Mohammed N, Hammouda HM. Advantaged Outcomes of Preemptive Living Donor Kidney Transplantation and the Effect of Bias. Exp Tech Urol Nephrol. 2019;. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Gadelkareem RA, Hameed DA, Moeen AM, El-Araby AM, Mahmoud MA, El-Taher AM, El-Haggagy AA, Ramzy MF. Living donor kidney transplantation in the hemodialysis-naive and the hemodialysis-exposed: A short term prospective comparative study. Afr J Urol. 2017;23:56-61. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Matter YE, Abbas TM, Nagib AM, Fouda MA, Abbas MH, Refaie AF, Denewar AA, Elmowafy AY, Sheashaa HA. Live donor kidney transplantation pearls: a practical review. Urol Nephrol Open Access J. 2017;5:00178. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | Vinson AJ, Kiberd BA, West K, Mannon RB, Foster BJ, Tennankore KK. Disparities in Access to Preemptive Repeat Kidney Transplant: Still Missing the Mark? Kidney360. 2022;3:144-152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | El-Agroudy AE, Donia AF, Bakr MA, Foda MA, Ghoneim MA. Preemptive living-donor kidney transplantation: clinical course and outcome. Transplantation. 2004;77:1366-1370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Saadi MG, El-Khashab SO, Mahmoud RMA. Renal transplantation experience in Cairo University hospitals. Egypt J Intern Med. 2016;28:116-122. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bakr MA, Ghoneim MA. Living donor renal transplantation, 1976 - 2003: the mansoura experience. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2005;16:573-583. [PubMed] |

| 15. | El-Husseini AA, Foda MA, Bakr MA, Shokeir AA, Sobh MA, Ghoneim MA. Pediatric live-donor kidney transplantation in Mansoura Urology & Nephrology Center: a 28-year perspective. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006;21:1464-1470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mosaad M, Hamdy AFA, Hassan NMA, Fouda MA, Mahmoud KM, Salem ME, El-Shahawy EL, Shokeir AA, Bakr MA, Ghoniem MA. Evaluation of live-donor kidney transplant survival in low body weight Egyptian children: 25 year-experience. Dial Transpl. 2012;33:1-8. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Fadel FI, Bazaraa HM, Badawy H, Morsi HA, Saadi G, Abdel Mawla MA, Salem AM, Abd Alazem EA, Helmy R, Fathallah MG, Ramadan Y, Fahmy YA, Sayed S, Eryan EF, Atia FM, ElGhonimy M, Shoukry AI, Shouman AM, Ghonima W, Salah Eldin M, Soaida SM, Ismail W, Salah DM. Pediatric kidney transplantation in Egypt: Results of 10-year single-center experience. Pediatr Transplant. 2020;24:e13724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Greene T, Zhang YL, Beck GJ, Froissart M, Hamm LL, Lewis JB, Mauer M, Navis GJ, Steffes MW, Eggers PW, Coresh J, Levey AS. Comparative performance of the CKD Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) and the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) Study equations for estimating GFR levels above 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;56:486-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 478] [Cited by in RCA: 480] [Article Influence: 30.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Migliori RJ, Simmons RL, Payne WD, Ascher NL, Sutherland DE, Najarian JS, Fryd D. Renal transplantation done safely without prior chronic dialysis therapy. Transplantation. 1987;43:51-55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Berthoux FC, Jones EH, Mehls O, Valderrábano F. Transplantation Report. 2: Pre-emptive renal transplantation in adults aged over 15 years. The EDTA-ERA Registry. European Dialysis and Transplant Association-European Renal Association. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996;11 Suppl 1:41-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Asderakis A, Augustine T, Dyer P, Short C, Campbell B, Parrott NR, Johnson RW. Pre-emptive kidney transplantation: the attractive alternative. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1998;13:1799-1803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Papalois VE, Moss A, Gillingham KJ, Sutherland DE, Matas AJ, Humar A. Pre-emptive transplants for patients with renal failure: an argument against waiting until dialysis. Transplantation. 2000;70:625-631. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Mange KC, Joffe MM, Feldman HI. Effect of the use or nonuse of long-term dialysis on the subsequent survival of renal transplants from living donors. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:726-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 352] [Cited by in RCA: 362] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kasiske BL, Snyder JJ, Matas AJ, Ellison MD, Gill JS, Kausz AT. Preemptive kidney transplantation: the advantage and the advantaged. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:1358-1364. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 350] [Cited by in RCA: 361] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Gill JS, Tonelli M, Johnson N, Pereira BJ. Why do preemptive kidney transplant recipients have an allograft survival advantage? Transplantation. 2004;78:873-879. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ashby VB, Kalbfleisch JD, Wolfe RA, Lin MJ, Port FK, Leichtman AB. Geographic variability in access to primary kidney transplantation in the United States, 1996-2005. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:1412-1423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Ishikawa N, Yagisawa T, Sakuma Y, Fujiwara T, Nukui A, Yashi M, Miyamoto N. Preemptive kidney transplantation of living related or unrelated donor-recipient combinations. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:2294-2296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Milton CA, Russ GR, McDonald SP. Pre-emptive renal transplantation from living donors in Australia: effect on allograft and patient survival. Nephrology (Carlton). 2008;13:535-540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Yoo SW, Kwon OJ, Kang CM. Preemptive living-donor renal transplantation: outcome and clinical advantages. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:117-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Gore JL, Danovitch GM, Litwin MS, Pham PT, Singer JS. Disparities in the utilization of live donor renal transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:1124-1133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Witczak BJ, Leivestad T, Line PD, Holdaas H, Reisaeter AV, Jenssen TG, Midtvedt K, Bitter J, Hartmann A. Experience from an active preemptive kidney transplantation program--809 cases revisited. Transplantation. 2009;88:672-677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kramer A, Stel VS, Geskus RB, Tizard EJ, Verrina E, Schaefer F, Heaf JG, Kramar R, Krischock L, Leivestad T, Pálsson R, Ravani P, Jager KJ. The effect of timing of the first kidney transplantation on survival in children initiating renal replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:1256-1264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Grams ME, Massie AB, Coresh J, Segev DL. Trends in the timing of pre-emptive kidney transplantation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:1615-1620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Grace BS, Clayton PA, Cass A, McDonald SP. Transplantation rates for living- but not deceased-donor kidneys vary with socioeconomic status in Australia. Kidney Int. 2013;83:138-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Patzer RE, Sayed BA, Kutner N, McClellan WM, Amaral S. Racial and ethnic differences in pediatric access to preemptive kidney transplantation in the United States. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:1769-1781. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Prezelin-Reydit M, Combe C, Harambat J, Jacquelinet C, Merville P, Couzi L, Leffondré K. Prolonged dialysis duration is associated with graft failure and mortality after kidney transplantation: results from the French transplant database. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2019;34:538-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Kim HY, Choi JY, Kwon HW, Jung JH, Han M, Park SK, Kim SB, Lee SK, Kim YH, Han DJ, Shin S. Comparison of Clinical Outcomes Between Preemptive Transplant and Transplant After a Short Period of Dialysis in Living-Donor Kidney Transplantation: A Propensity-Score-Based Analysis. Ann Transplant. 2019;24:75-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Prezelin-Reydit M, Madden I, Macher MA, Salomon R, Sellier-Leclerc AL, Roussey G, Lahoche A, Garaix F, Decramer S, Ulinski T, Fila M, Dunand O, Merieau E, Pongas M, Zaloszyc A, Baudouin V, Bérard E, Couchoud C, Leffondré K, Harambat J. Preemptive Kidney Transplantation Is Associated With Transplantation Outcomes in Children: Results From the French Kidney Replacement Therapy Registry. Transplantation. 2022;106:401-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Goldfarb-Rumyantzev A, Hurdle JF, Scandling J, Wang Z, Baird B, Barenbaum L, Cheung AK. Duration of end-stage renal disease and kidney transplant outcome. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:167-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Davis CL. Preemptive transplantation and the transplant first initiative. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2010;19:592-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Kallab S, Bassil N, Esposito L, Cardeau-Desangles I, Rostaing L, Kamar N. Indications for and barriers to preemptive kidney transplantation: a review. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:782-784. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Boulware LE, Hill-Briggs F, Kraus ES, Melancon JK, Senga M, Evans KE, Troll MU, Ephraim P, Jaar BG, Myers DI, McGuire R, Falcone B, Bonhage B, Powe NR. Identifying and addressing barriers to African American and non-African American families' discussions about preemptive living related kidney transplantation. Prog Transplant. 2011;21:97-104; quiz 105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Alsharani M, Basonbul F, Yohanna S. Low Rates of Preemptive Kidney Transplantation: A Root Cause Analysis to Identify Opportunities for Improvement. J Clin Med Res. 2021;13:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Coorey GM, Paykin C, Singleton-Driscoll LC, Gaston RS. Barriers to preemptive kidney transplantation. Am J Nurs. 2009;109:28-37; quiz 38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Gadelkareem RA, Azoz NM, Shahat AA, Abdelhafez MF, Faddan AA, Reda A, Farouk M, Fawzy M, Osman MM, Elgammal MA. Experience of a tertiary-level urology center in the clinical urological events of rare and very rare incidence. III. Psychourological events: 2. Phobia of renal failure due to loin pain. Afr J Urol. 2020;26:35. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Paris W, Nour B. Organ transplantation in Egypt. Prog Transplant. 2010;20:274-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Egyptian Urological Association.

Specialty type: Transplantation

Country/Territory of origin: Egypt

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Salvadori M, Italy; Sureshkumar KK, United States S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Ma YJ