Published online Dec 25, 2025. doi: 10.5501/wjv.v14.i4.115071

Revised: November 19, 2025

Accepted: December 11, 2025

Published online: December 25, 2025

Processing time: 79 Days and 16.3 Hours

In tropical Asia, arbovirus-induced encephalitis continues to be a serious public health issue. Encephalitis is caused by wide range of neurotropic pathogens, and flaviviruses are one of the main causative agents in the area. Sri Lanka reports a considerable number of central nervous system infections annually. Both dengue and Japanese encephalitis are endemic, and cases of Zika and West Nile virus infections were reported occasionally in Sri Lanka. Although reported number of Japanese encephalitis cases has reduced in the past, aetiological diagnosis in ma

To detect dengue virus (DENV) infections in individuals in the central region of Sri Lanka who were clinically suspected of having encephalitis.

A retrospective observational analysis was conducted on 99 cerebrospinal fluid samples received to a virology laboratory from patients in the central part of Sri Lanka who were clinically suspected of having encephalitis. Samples were ana

DENV aetiology was detected in 6 (6.06%) cerebrospinal fluid samples, and all were confirmed as DENV infections. A single positive result (1.01%) was yielded through RT-PCR and was identified as DENV serotype 3. Serology testing detected 05 (5.05%) anti-dengue IgM positives and further investigation indicated probable DENV aetiology. Among positives 02 (33.33%) were children (aged less than 14 years), and rest were adults.

These findings underscore the presence of DENV-associated central nervous system infections and highlight the need for broader surveillance and more advanced diagnostic approaches in the future.

Core Tip: Encephalitis due to arbovirus infections is a significant public health problem in tropical Asia. Encephalitis is caused by wide range of neurotropic pathogens, and flaviviruses are one of the main causative agents in tropics. Sri Lanka reports a considerable number of central nervous system infections annually. Both dengue and Japanese encephalitis are endemic, and cases of Zika and West Nile virus infections were reported in Sri Lanka. This study describes dengue virus (DENV) infections in clinically suspected patients with encephalitis in the central part of the country. A retrospective observational analysis was conducted on 99 cerebrospinal fluid samples. One sample was positive for dengue serotype 3 RNA and five samples were positive for dengue immunoglobulin M indicating recent DENV infections. These findings highlight the presence of DENV central nervous system infections and emphasize the need for broader surveillance and advanced diagnostics in future.

- Citation: Perera I, Weerathunga A, Arachchige N, Rajamanthri L, Fernando S, Muthugala R. Detection of dengue virus encephalitis in central part of Sri Lanka. World J Virol 2025; 14(4): 115071

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3249/full/v14/i4/115071.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5501/wjv.v14.i4.115071

Central nervous system (CNS) infections encompass a broad range of pathological conditions, including meningitis, encephalitis, and brain abscesses[1]. These infections represent a significant global health concern, with an estimated incidence of 389 cases per 100000 individuals reported between 1990 and 2016[2]. In Sri Lanka, epidemiological data indicate that approximately 1000-1500 cases of meningitis and 150-250 cases of encephalitis are reported annually[3]. Notably, recent epidemiological reports highlight a considerable increase in the incidence of both conditions in 2023[4].

Over 100 different pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites, have been reported to cause CNS infections[5]. Among these, viruses are recognized as the predominant causative agents of meningitis and encephalitis[3]. Viruses from all families possess the potential to invade the CNS[6]. A significant proportion of viral CNS infections are attributed to arthropod-borne viruses (arboviruses), a diverse group of viruses transmitted by vectors such as mos

The family Flaviviridae comprises four genera: Flavivirus, Pestivirus, Hepacivirus, and Pegivirus[9]. Among these, the genus Flavivirus is responsible for some of the most severe arboviral infections known to affect humans[10]. Flaviviruses that have the ability to invade the CNS and cause infections are regarded as neurotropic[11]. Notable neuroinvasive flaviviruses include dengue virus (DENV), West Nile virus (WNV), Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), Zika virus (ZIKV), and tick-borne encephalitis virus, all of which demonstrate the ability to cross the blood-brain barrier and establish in

DENV is a mosquito-borne flavivirus that is primarily transmitted by Aedes species, which is classified into four distinct serotypes, DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3, and DENV-4[14]. Among these, DENV-2 and DENV-3 are more fre

Encephalitis and meningoencephalitis have been reported in approximately 4%-21% of dengue cases, which highlights the neuroinvasive potential of the virus. In Sri Lanka, dengue fever continues to pose a significant health burden, with the country recording its third-largest outbreak in 2023 (89799 cases and 62 deaths), following outbreaks in 2017 (186101 cases and 440 deaths) and 2019 (105049 cases and 157 deaths)[17]. Given the significant burden of dengue-related neurological diseases and other CNS infections, enhanced clinical awareness is essential.

Early and effective treatment of CNS infections depends on rapid and accurate diagnosis. However, clinical diagnosis is often challenging due to the non-specific and overlapping symptoms of CNS infections, which may be caused by a wide range of pathogens including viruses, bacteria, fungi, and protozoa. Clinical observations are not particularly useful in determining the specific CNS infection[18].

Therefore, laboratory-based investigations are essential[19]. These include molecular techniques such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), cell culture of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and serological tests like enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for detecting pathogen-specific immunoglobulin (Ig) M or IgG antibodies in CSF or serum[20]. Among these, CSF is the most widely used specimen type in the diagnosis of CNS infections[21]. In developing countries such as Sri Lanka where CNS infections are more prevalent, diagnosing them poses significant challenges. These are due to the limited access to rapid diagnostic facilities and lack of epidemiological data. Although nucleic acid-based diagnostics facilitate rapid and accurate diagnosis, they are not readily available in developing countries. In such contexts, pre

This was a retrospective, cross-sectional, observational study.

This study protocol was approved by the Research and Ethics Committee of the National Hospital Kandy, approval No. NHK/ERC/11/2021. Informed consent was waived due to retrospective nature of the study and data dissemination without any personal identification data.

This study was designed as a retrospective, observational analysis conducted at the Department of Molecular Biology, Medical Research Institute and National Hospital Kandy, Sri Lanka. The remaining portions of stored CSF samples received to the virology laboratory for routine diagnosis in central part of the country from patients with suspected CNS infections (meningitis and encephalitis) from January 2023 to December 2023 were utilized in this study.

During that period 211 CSF samples were received at the laboratory from clinically diagnosed patients with encephalitis for laboratory diagnosis. Of them only 198 samples had adequate remaining volume (at least 150 μL of volume), and every other sample was selected to the study based on laboratory serial number.

All the samples were stored at -80 °C under continuous temperature monitoring. The clinical diagnosis of CNS in

Reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) was performed on 99 CSF samples to detect flaviviral RNA according to the method described by Tanaka[22].

Viral RNA was extracted from CSF samples using the QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN®, Germany), a locally validated commercial kit, following the manufacturer’s protocol. From each sample, 60 μL of RNA eluate was obtained and subsequently stored at -70 °C until further analysis.

Universal primers targeting flaviviruses were selected based on the published protocol by Tanaka[22] and synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies, United States. The primer pair used in this study based on yellow fever (YF), YF-1 (5′-GGTCTCCTCTAACCTCTAG-3′) and YF-3 (5′-GAGTGGATGACCACGGAAGACATGC-3′) was originally designed to maximize homology across six flaviviruses (YF, MVE, JEV, DENV-2, DENV-3, and DENV-4)[22]. These primers were derived from the yellow fever virus 17D vaccine strain, based on the nucleotide sequence reported by Rice et al[23]. The primer binding region corresponds to a highly conserved sequence spanning the nonstructural protein 5 and the 3′-untranslated region, specifically nucleotides 10709-10052 of the yellow fever virus genome[22].

In-house RT-PCR was performed in 25 μL reaction volumes using Promega reagents (Promega, United States) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The final concentration of each Flavivirus universal primer (YF-1 and YF-3) was 20 μM. Each reaction mixture contained 12.5 μL of 2 × qPCR Master Mix, 0.5 μL of GoScript Reverse Transcriptase,

PCR products were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. A 20 g/L agarose gel was prepared in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer. For each sample, 10 μL of PCR product was mixed with 2 μL of loading dye and loaded onto the gel alongside a 100 bp DNA ladder. Electrophoresis was performed at 100 V for 50 minutes, and DNA bands were visualized under UV illumination. Gel images were captured using a POLAR camera system (Bio-Rad, United States) and analyzed using Quantity One® software.

The analytical sensitivity of the RT-PCR assay was evaluated using a serial dilution of the JE vaccine. The lowest detectable concentration was determined to be 2.7 × 10-1 infectious units per mL. Analytical specificity was assessed using RNA and DNA from non-flaviviral viruses, including Measles, Mumps, Rubella, severe acute respiratory distress syn

A real-time reverse transcription PCR assay was conducted to determine DENV serotypes in dengue-positive elutes using dengue-specific primers and probes. The final concentration of primers and probes was 20 μM. Each reaction was carried out in a total volume of 25 μL using Promega reagents (Promega, United States), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A volume of 5 μL of extracted RNA was added to the RT- real-time reverse transcription PCR mixture. Positive controls for each serotype (DENV-1 to DENV-4) and nuclease-free water as a negative control were included in each run. Amplification was conducted on a Bio-Rad CFX96 thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, United States) using a previously optimized thermal cycling protocol. The cycling conditions consisted of reverse transcription at 45 °C for 15 minutes, initial denaturation at 95 °C for 10 minutes, followed by 44 cycles of annealing at 95 °C for 0.15 minutes, and extension at 60 °C for 0.45 minutes. The reaction was held at 4 °C until further analysis.

Commercial dengue IgM-capture ELISA (IgM-ELISA) was carried out on 68 CSF samples with adequate sample volume to detect IgM antibodies indicative of a possible recent dengue/flavivirus infection.

The SERION ELISA classic DENV superior IgM kit (Cat No. ESR114m, Serion Immunodiagnostica, Germany), a com

The assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s protocol with modification to sample volume to accom

Clinical, laboratory and surveillance records of Dengue PCR and IgM positive samples were traced retrospectively and data was obtained. Only clinical diagnosis, age distribution (child or adult), resident district and microbiological investigation results analyzed anonymously.

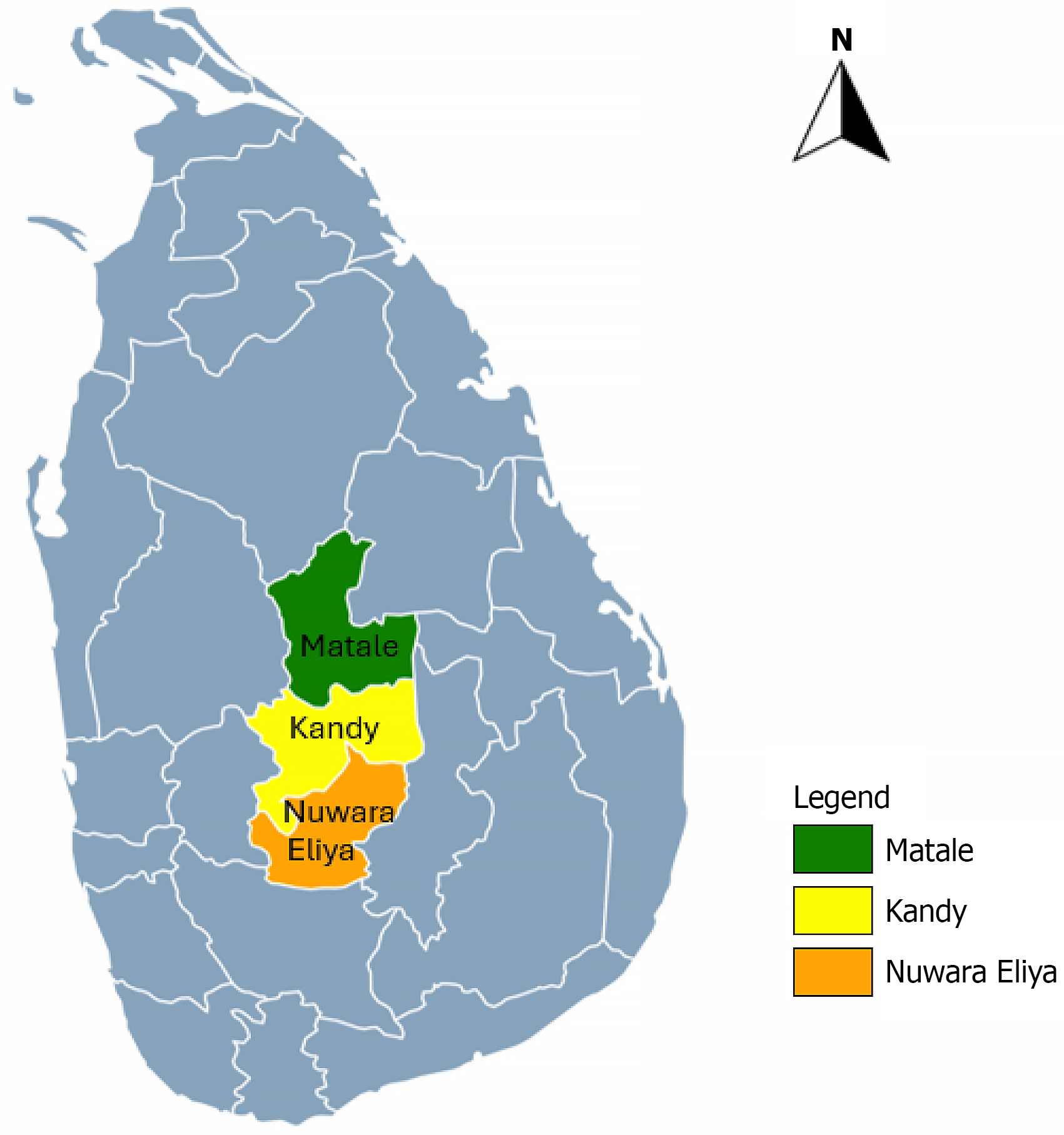

All selected CSF samples were collected from patients who had clinical features of encephalitis or both meningitis and encephalitis, according to the treating clinician. Of these patients, sixty were from pediatric (< 14 years) age group, and the remainder were from adults. Among the 99 CSF samples analyzed, probable DENV aetiology was identified in 6 samples (6.06%). Of these, one sample (1.01%) was confirmed by RT-PCR, while five samples (5.05%) were identified using IgM-ELISA. There was no overlap between the positive results of the two methods; the RT-PCR-positive sample tested negative by ELISA, and all five ELISA-positive samples were negative by RT-PCR. Positive cases were geographically concentrated in the Kandy and Matale districts (Figure 1). Among the six positive patients, two were pediatric cases and four were adults (Table 1).

| Number | Age (years) | Clinical syndrome | District | Diagnosis method |

| 1 | < 14 | Encephalitis | Kandy | RT-PCR |

| 2 | > 14 | Encephalitis | Kandy | IgM-ELISA |

| 3 | > 14 | Encephalitis | Matale | IgM-ELISA |

| 4 | < 14 | Encephalitis | Kandy | IgM-ELISA |

| 5 | > 14 | Encephalitis | Matale | IgM-ELISA |

| 6 | > 14 | Meningitis/encephalitis | Kandy | IgM-ELISA |

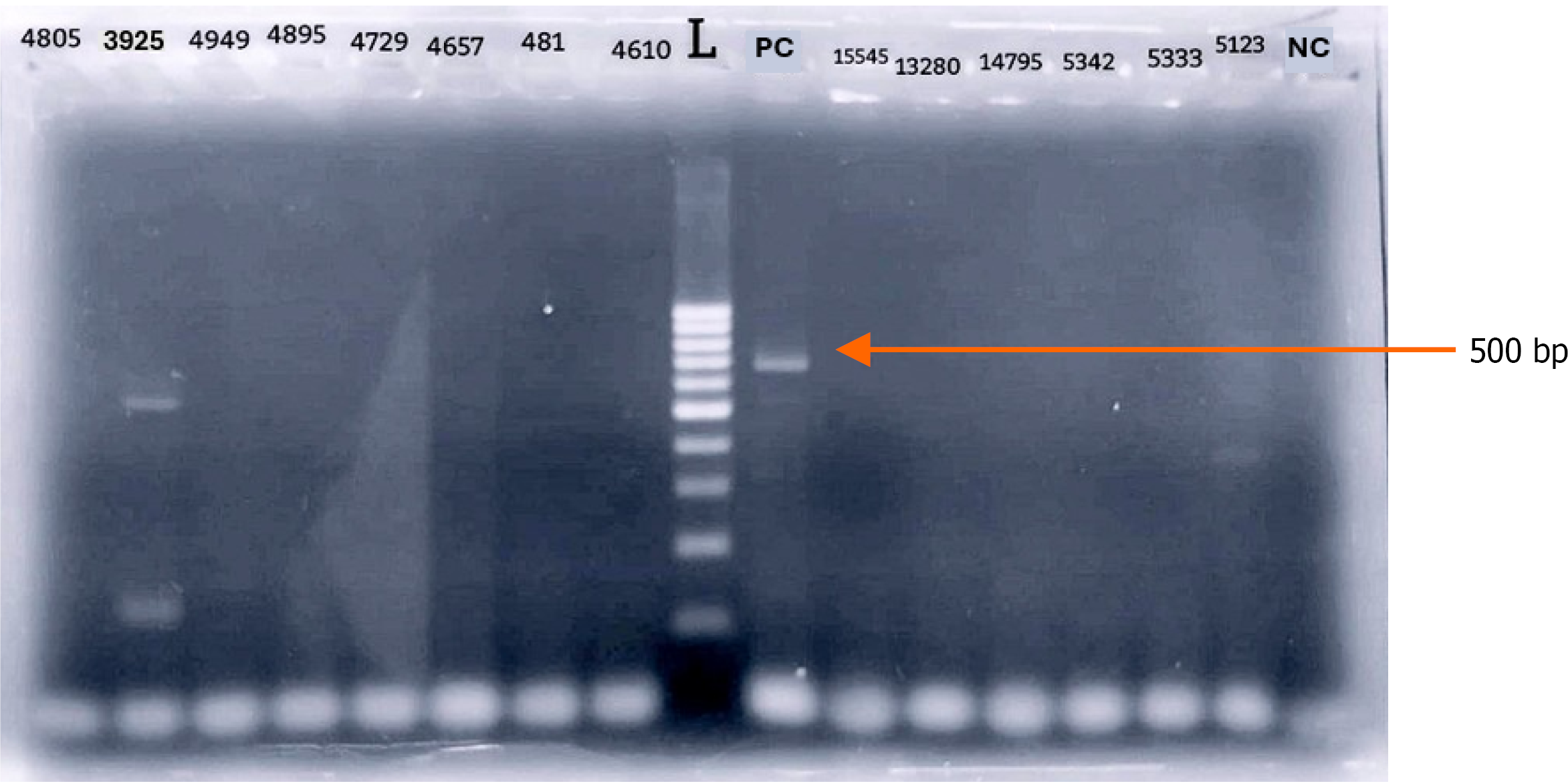

The RT-PCR positive sample produced a distinct band between 500-600 base pairs on agarose gel electrophoresis (Figure 2), consistent with DENV amplification as reported by Tanaka[22].

Based on this observation, real-time RT-PCR was conducted on the same eluate using DENV-specific primers and probes targeting all four serotypes (DENV-1 to DENV-4) to confirm the presence of DENV and identify the specific serotype. A clear amplification curve was observed (Figure 3), with a quantification cycle value of 23.27, confirming the presence of DENV-3 as the causative agent of CNS infection in this case.

IgM-ELISA was conducted on 68 CSF samples selected from the original pool of 99, based on the availability of adequate sample volume. Samples with insufficient remaining volume were excluded from ELISA testing. Of the 68 samples tested, five (7.35%) were positive for anti-dengue IgM antibodies. Since there was no overlap between the ELISA and RT-PCR positive results, these five ELISA-positive cases were considered out of the 99 samples analyzed, corresponding to an overall positivity rate of 5.05%.

Based on the diagnostic laboratory data, those five samples were negative for Herpes Simplex virus, Varicella zoster virus, Cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus and alphavirus genome by PCR and bacterial cultures were negative. Under acute encephalitis syndrome, all suspected cases with encephalitis are investigated for JE by the National JE Surveillance Laboratory and Epidemiology Unit. Based on surveillance data, these five cases were excluded for JE.

This study was conducted to identify the causative agents of CNS infections, with a particular focus on DENV due to their known role in viral meningitis and encephalitis globally, including in Sri Lanka. Notably, most published studies on flavivirus-associated CNS infections have focused on the Western Province. This study investigates the population in the Central Province, encompassing Kandy, Matale, and Nuwara Eliya districts, which collectively comprise the second-largest population in the country. A notable increase in dengue cases was recorded in this region in 2023, ranking third highest number of reported dengue cases in Sri Lanka, underscoring the need for region specific research into neuroinvasive viral pathogens.

A similar study by Lohitharajah et al[24] in Colombo identified a viral aetiology in 27.3% of patients, with flaviviruses accounting for 21.21%. This means that 78.79% of cases had no confirmed viral cause. Similarly, in the present study, flaviviral aetiology was identified in only 6.06% of samples. These discrepancies may reflect regional epidemiological variations, differences in the periods of data collection, or the use of different clinical samples and diagnostic methods. Across both developed and developing regions, a majority of meningitis and encephalitis cases remain without a confirmed cause, with undiagnosed proportions reported to exceed 50% and reach as high as 85% despite comprehensive diagnostic efforts[25,26].

Patients testing negative for flaviviruses may have been infected by other bacterial, viral (non-flaviviral), or autoim

In recent years, several molecular diagnostic techniques employing generic approaches have been developed for detecting flavivirus infections. Various research groups have proposed universal primer sets designed to amplify conserved regions particularly those encoding non-structural proteins across a broad range of flavivirus genomes[29,30]. Kuno[31] recommended a two-stage diagnostic strategy, an initial screening using broad-range, group-reactive primers to detect the presence of flaviviruses at the genus level, followed by the use of species-specific primers to accurately identify the infecting virus.

This two-step approach was adopted in the present study. Initial detection was performed using a conventional RT-PCR assay targeting conserved flavivirus genomic regions with universal primers, allowing broad-spectrum detection in a setting where multiple flaviviruses may co-circulate. Upon identification of a positive band, a second round of testing was carried out using real-time RT-PCR with DENV specific primers (targeting serotypes 1 to 4), which confirmed the presence of DENV-3. This sequential approach of broad-range detection followed by specific confirmation enhanced diagnostic sensitivity in the initial phase and improved specificity in the confirmatory step.

The patient who tested positive for DENV-3 was initially clinically diagnosed with suspected dengue fever and later developed encephalitis. This finding is consistent with previous research in Sri Lanka. In 2009, all four DENV serotypes co-circulate in the country, serotypes 2 and 3 have been the predominant causes of clinically apparent cases.

Although DENV-3 was the dominant strain prior to 2009, it was notably absent from surveillance data between 2009 and mid-2016. However, a resurgence of DENV-3 cases was observed from late 2019 onward[32]. A large-scale study conducted in western part of the country; among 1796 clinically suspected dengue patients between May 2019 and April 2021 revealed that 472 cases (37.97%) were due to DENV-3. Notably, all cases of dengue-associated encephalitis in that cohort were attributed to the DENV-3 serotype[33]. The findings of the current study align with this trend, further reinforcing the association between DENV-3 and neurological complications such as encephalitis.

This study used both RT-PCR and ELISA to identify DENV infections. RT-PCR targeted viral RNA while ELISA detected IgM antibodies. The RT-PCR-positive sample was negative in ELISA, and none of the ELISA-positive samples were confirmed by RT-PCR. These differences can be attributed to the distinct diagnostic windows of the two methods.

Although cross-reactivity with JEV was excluded through specific testing, the possibility of serological cross-reactivity with other flaviviruses such as ZIKV and WNV cannot be entirely ruled out. However, based on local epidemiological data, ZIKV infections show very low prevalence in Sri Lanka, with only a limited number of antibody positives reported in previous studies[34,35]. Similarly, WNV IgM detection in serum samples was reported once in Sri Lanka[36].

Flaviviruses typically exhibit a short viremic period, during which the virus can be detected in the serum or plasma of infected individuals, most often within the first 5 days after the onset of the disease. The likelihood of detection significantly decreases after the first week as viremia clears. The likelihood of detection significantly decreases after the first week as viremia clears. RT-PCR was likely unable to detect the virus in ELISA-positive cases because those samples were collected after the viremic phase had ended[37]. However, conducting RT-PCR during this brief viremic period is challenging and may not always be feasible.

In contrast, the decrease in viremia coincides with the appearance of IgM antibodies. Following the onset of symptoms, around 5-7 days into the infection, the body begins to mount an immune response against the invading virus. IgM antibodies are among the first antibodies to be produced during this immune response, and they reach their peak levels in the bloodstream around 15 days after the onset of symptoms. In some cases, such as with DENV infections, IgM antibodies may persist in the bloodstream for several months following the acute phase of the infection[38]. In other instances, such as WNV infection, IgM antibodies may persist in the bloodstream for even longer periods, lasting for years after the initial infection. The presence of IgM antibodies serves as a marker of recent or ongoing infection and can be detected through serological tests like ELISA[39]. Although IgM kit with less cross reactivity was used in this study, certain degree of cross reactivity cannot be ruled out without neutralization assays. Detection of IgM antibodies can serve as a valuable diagnostic tool for detecting flavivirus infections, particularly during the convalescent phase when viral RNA may no longer be detectable by PCR. These findings underscore the necessity of employing both serological and molecular methods in flavivirus diagnostics.

Although specific antiviral treatments for dengue and other flavivirus infections are currently unavailable, accurate diagnosis remains crucial for patient care and public health measures. Early identification enables timely supportive management, such as hydration, pain management, and supportive therapies to address neurological symptoms, which can significantly influence patient outcomes. Moreover, diagnosis of CNS infections of dengue facilitates better epidemiological understanding and informs region-specific surveillance and vector control strategies, particularly relevant in a country like Sri Lanka.

This study demonstrates the presence of DENV-associated CNS infections in the Central Province of Sri Lanka, with a 6.06% positivity rate among suspected encephalitis cases. DENV-3 was identified as the causative agent in one patient, reinforcing its established association with neurological complications. The differences observed between RT-PCR and IgM-ELISA results underscore the importance of integrating both molecular and serological tools to improve diagnostic accuracy. These findings underscore the importance of sustained surveillance, advanced diagnostic capacity, and broader investigation into other viral and immune-mediated causes of CNS infections to reduce the proportion of CNS infections that remain undiagnosed and improve patient outcomes in Sri Lanka.

The authors would like to acknowledge the staff of the Virology Laboratory, National Hospital Kandy and the Molecular Biology Laboratory at the Medical Research Institute, Sri Lanka, for their immense support. Support given by Dr. Atheeka Akram, acting consultant virologist is appreciated. We would like to acknowledge Prof Dr. Andreas Nitsche and his team at the Robert Koch Institute, Germany for the providing reagents for molecular studies under IDEA project.

| 1. | Giovane RA, Lavender PD. Central Nervous System Infections. Prim Care. 2018;45:505-518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Robertson FC, Lepard JR, Mekary RA, Davis MC, Yunusa I, Gormley WB, Baticulon RE, Mahmud MR, Misra BK, Rattani A, Dewan MC, Park KB. Epidemiology of central nervous system infectious diseases: a meta-analysis and systematic review with implications for neurosurgeons worldwide. J Neurosurg. 2019;130:1107-1126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dheerasekara WKH, Muthugala MARV, Liyanapathirana V. Epidemiology and diagnosis of viral and bacterial central nervous system infections in Sri Lanka: A Narrative review. Sri Lankan J Infec Dis. 2023;13. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Epidemiology Unit. Weekly Epidemiological Reports. [cited 06 October 2025]. Available from: https://www.epid.gov.lk/weekly-epidemiological-report. |

| 5. | Thanh TT, Casals-Pascual C, Ny NTH, Ngoc NM, Geskus R, Nhu LNT, Hong NTT, Duc DT, Thu DDA, Uyen PN, Ngoc VB, Chau LTM, Quynh VX, Hanh NHH, Thuong NTT, Diem LT, Hanh BTB, Hang VTT, Oanh PKN, Fischer R, Phu NH, Nghia HDT, Chau NVV, Hoa NT, Kessler BM, Thwaites G, Tan LV. Value of lipocalin 2 as a potential biomarker for bacterial meningitis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;27:724-730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Handique SK. Viral infections of the central nervous system. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2011;21:777-794, vii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Murugesan R, Prabhu S, Caleb JTD, Francis YM, Pulidindi IN. Arboviruses and COVID-19: Global Health Challenges and Human Enhancement Technologies. Bioengineering (Basel). 2025;12:725. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Varghese J, De Silva I, Millar DS. Latest Advances in Arbovirus Diagnostics. Microorganisms. 2023;11:1159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Simmonds P, Becher P, Bukh J, Gould EA, Meyers G, Monath T, Muerhoff S, Pletnev A, Rico-Hesse R, Smith DB, Stapleton JT; Ictv Report Consortium. ICTV Virus Taxonomy Profile: Flaviviridae. J Gen Virol. 2017;98:2-3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 391] [Cited by in RCA: 620] [Article Influence: 68.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sips GJ, Wilschut J, Smit JM. Neuroinvasive flavivirus infections. Rev Med Virol. 2012;22:69-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Maximova OA, Pletnev AG. Flaviviruses and the Central Nervous System: Revisiting Neuropathological Concepts. Annu Rev Virol. 2018;5:255-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Daep CA, Muñoz-Jordán JL, Eugenin EA. Flaviviruses, an expanding threat in public health: focus on dengue, West Nile, and Japanese encephalitis virus. J Neurovirol. 2014;20:539-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Marinho PES, Kroon EG. Flaviviruses as agents of childhood central nervous system infections in Brazil. New Microbes New Infect. 2019;31:100572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Meyding-Lamadé U, Craemer E, Schnitzler P. Emerging and re-emerging viruses affecting the nervous system. Neurol Res Pract. 2019;1:20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Dhenni R, Karyanti MR, Putri ND, Yohan B, Yudhaputri FA, Ma'roef CN, Fadhilah A, Perkasa A, Restuadi R, Trimarsanto H, Mangunatmadja I, Ledermann JP, Rosenberg R, Powers AM, Myint KSA, Sasmono RT. Isolation and complete genome analysis of neurotropic dengue virus serotype 3 from the cerebrospinal fluid of an encephalitis patient. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:e0006198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kulkarni R, Pujari S, Gupta D. Neurological Manifestations of Dengue Fever. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2021;24:693-702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Medical Statistics Unit, Ministry of Health. Annual Health Bulletin 2022-2023. [cited 06 October 2025]. Available from: https://www.health.gov.lk/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/AHB_2022-20232025-01-22-compressed.pdf. |

| 18. | Guo Y, Yang Y, Xu M, Shi G, Zhou J, Zhang J, Li H. Trends and Developments in the Detection of Pathogens in Central Nervous System Infections: A Bibliometric Study. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:856845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ranawaka UK. The challenge of treating central nervous system infections. Ceylon Med J. 2015;60:155-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Vila J, Bosch J, Muñoz-Almagro C. Molecular diagnosis of the central nervous system (CNS) infections. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin (Engl Ed). 2020;S0213-005X(20)30168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Archibald LK, Quisling RG. Central Nervous System Infections. In: Layon A, Gabrielli A, Friedman W, editors. Textbook of Neurointensive Care. London: Springer, 2013. |

| 22. | Tanaka M. Rapid identification of flavivirus using the polymerase chain reaction. J Virol Methods. 1993;41:311-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rice CM, Lenches EM, Eddy SR, Shin SJ, Sheets RL, Strauss JH. Nucleotide sequence of yellow fever virus: implications for flavivirus gene expression and evolution. Science. 1985;229:726-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 681] [Cited by in RCA: 669] [Article Influence: 16.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lohitharajah J, Malavige N, Arambepola C, Wanigasinghe J, Gamage R, Gunaratne P, Ratnayake P, Chang T. Viral aetiologies of acute encephalitis in a hospital-based South Asian population. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17:303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Wang H, Zhao S, Wang S, Zheng Y, Wang S, Chen H, Pang J, Ma J, Yang X, Chen Y. Global magnitude of encephalitis burden and its evolving pattern over the past 30 years. J Infect. 2022;84:777-787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Saha S. Unearthing the Unknown Causes of Meningitis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103:544-545. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hoang HE, Robinson-Papp J, Mu L, Thakur KT, Gofshteyn JS, Kim C, Ssonko V, Dugue R, Harrigan E, Glassberg B, Harmon M, Navis A, Hwang MJ, Gao K, Yan H, Jette N, Yeshokumar AK. Determining an infectious or autoimmune etiology in encephalitis. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2022;9:1125-1135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Gable MS, Sheriff H, Dalmau J, Tilley DH, Glaser CA. The frequency of autoimmune N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis surpasses that of individual viral etiologies in young individuals enrolled in the California Encephalitis Project. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:899-904. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 467] [Cited by in RCA: 527] [Article Influence: 37.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Daidoji T, Morales Vargas RE, Hagiwara K, Arai Y, Watanabe Y, Nishioka K, Murakoshi F, Garan K, Sadakane H, Nakaya T. Development of genus-specific universal primers for the detection of flaviviruses. Virol J. 2021;18:187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Vina-Rodriguez A, Sachse K, Ziegler U, Chaintoutis SC, Keller M, Groschup MH, Eiden M. A Novel Pan-Flavivirus Detection and Identification Assay Based on RT-qPCR and Microarray. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:4248756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kuno G. Universal diagnostic RT-PCR protocol for arboviruses. J Virol Methods. 1998;72:27-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Malavige GN, Jeewandara C, Ghouse A, Somathilake G, Tissera H. Changing epidemiology of dengue in Sri Lanka-Challenges for the future. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2021;15:e0009624. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Abeynayake J. Distribution of Dengue Virus Serotypes during the COVID 19 Pandemic in Sri Lanka. Virol Immunol J. 2022;6:000299. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 34. | Ngwe Tun MM, Raini SK, Fernando L, Gunawardene Y, Inoue S, Takamatsu Y, Urano T, Muthugala R, Hapugoda M, Morita K. Epidemiological evidence of acute transmission of Zika virus infection in dengue suspected patients in Sri-Lanka. J Infect Public Health. 2023;16:1435-1442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Abeygoonawardena H, Wijesinghe N, Navaratne V, Balasuriya A, Nguyen TTN, Moi ML, De Silva AD. Serological Evidence of Zika virus Circulation with Dengue and Chikungunya Infections in Sri Lanka from 2017. J Glob Infect Dis. 2023;15:113-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Lohitharajah J, Malavige GN, Chua AJ, Ng ML, Arambepola C, Chang T. Emergence of human West Nile Virus infection in Sri Lanka. BMC Infect Dis. 2015;15:305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Martins IC, Ricardo RC, Santos NC. Dengue, West Nile, and Zika Viruses: Potential Novel Antiviral Biologics Drugs Currently at Discovery and Preclinical Development Stages. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14:2535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Domingo C, de Ory F, Sanz JC, Reyes N, Gascón J, Wichmann O, Puente S, Schunk M, López-Vélez R, Ruiz J, Tenorio A. Molecular and serologic markers of acute dengue infection in naive and flavivirus-vaccinated travelers. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;65:42-48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Murray KO, Garcia MN, Yan C, Gorchakov R. Persistence of detectable immunoglobulin M antibodies up to 8 years after infection with West Nile virus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89:996-1000. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/