Published online Dec 25, 2025. doi: 10.5501/wjv.v14.i4.113507

Revised: October 9, 2025

Accepted: December 16, 2025

Published online: December 25, 2025

Processing time: 114 Days and 2.6 Hours

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has had profound physical, psychological, and social consequences, with lasting effects on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) among people with a history of COVID-19.

To synthesize the current evidence on HRQoL and long-term health outcomes among people with a history of COVID-19 in India.

We incorporated studies from India reporting post-COVID HRQoL outcomes using validated instruments, including the 5-level EuroQol 5-Dimensional questionnaire, the EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale, the Short Form-36 Health Survey, the World Health Organization Quality of Life-Brief Version, and the European Health Interview Survey-Quality of Life. Pooled mean 5-level EuroQol 5-Dimensional questionnaire scores with 95%CIs were calculated for HRQoL. Adjusted odds ratios were pooled for comorbidity, disease severity, intensive care unit admission, age, sex, and vaccination status using random-effects models.

Three studies (n = 1526) reported EuroQol instruments, with the 5-level EuroQol 5-Dimensional questionnaire utility scores suitable for quantitative pooling. The pooled mean utility was 0.83 (95%CI: 0.75-0.92), although heterogeneity was high because the included studies represented clinically distinct populations. Across all studies, several determinants were consistently associated with impaired HRQoL. Older adults (≥ 60 years) had higher odds of poor HRQoL [pooled odds ratio (OR) = 1.83, 95%CI: 1.43-2.35], and females were more likely to experience impaired HRQoL (pooled OR = 1.74, 95%CI: 1.44-2.10), whereas males had a lower risk (pooled OR = 0.58, 95%CI: 0.48-0.70). Being unvaccinated increased the likelihood of persistent symptoms or reduced HRQoL (pooled OR = 1.60, 95%CI: 1.21-2.14). Comorbidity (pooled OR = 1.94, 95%CI: 1.43-2.63) and severe acute COVID-19 or intensive care unit admission (pooled OR = 2.77, 95%CI: 2.13-3.59) were also strongly associated with poorer HRQoL Six additional studies utilizing disparate instruments (EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale, Short Form-36 Health Survey, World Health Organization Quality of Life-Brief Version, European Health Interview Survey-Quality of Life) were excluded from quantitative synthesis due to measurement heterogeneity.

Post-COVID HRQoL in people with a history of COVID-19 in India is suboptimal, with greater impairment observed among older adults, females, patients with comorbidities or severe disease, and unvaccinated indi

Core Tip: This systematic review and meta-analysis is the first to comprehensively assess post- coronavirus disease 2019 health-related quality of life in India using validated instruments such as 5-level EuroQol 5-Dimensional questionnaire, Short Form-36 Health Survey, World Health Organization Quality of Life-Brief Version, and St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire. Findings highlight that overall health-related quality of life recovery was suboptimal, especially among vulnerable groups including older adults, women, and patients with chronic conditions who experienced disproportionately poorer outcomes. The study underscores the importance of targeted, multidisciplinary rehabilitation strategies that address physical, psychological, and social domains of health to improve long-term recovery in post- coronavirus disease 2019 populations.

- Citation: Roy S, Samanta P, Sen A, Ghosh A, Basu S. Post-COVID-19 health-related quality of life in India: A systematic review and meta-analytic assessment of recovery outcomes. World J Virol 2025; 14(4): 113507

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3249/full/v14/i4/113507.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5501/wjv.v14.i4.113507

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, instigated by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has resulted in unprecedented global health challenges, affecting millions of lives and healthcare systems worldwide[1]. Recent estimates from the World Health Organization suggest that 10%-20% of individuals globally experience long COVID following SARS-CoV-2 infection, with variation by age, sex, and severity of acute illness[2,3]. In India, cohort studies and national surveys have reported a prevalence ranging from 15% to 30% among recovered patients, with higher rates among those with comorbidities and severe disease[4]. As of 2024, India has recorded over 45 million confirmed cases and close to 5.5 Lakh deaths due to COVID-19, positioning itself as one of the hardest-hit nations globally[5]. While the acute phase of COVID-19 has been the primary focus of clinical management and research, subsequent evidence indicates that a significant proportion of individuals continue to experience persistent symptoms and health complications long after the resolution of the initial infection[6]. This condition, often referred to as "long COVID", has profound implications for patients' health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and long-term health outcomes[7].

HRQoL is a multidimensional construct that encompasses the physical, psychological, and social aspects of well-being[8] and serves as a crucial indicator of the overall impact of chronic diseases and medical conditions on individuals' daily lives. In the context of long-COVID, patients report a wide range of enduring symptoms, including fatigue (13%-87%), dyspnea (10%-71%), chest pain/tightness (12%-44%), cough (17%-34%), cognitive impairment, and psychological distress (13%-35%), which collectively impair their HRQoL[9-11]. Moreover, long-term health complications associated with COVID-19, such as cardiovascular, respiratory, neurological, and renal further accentuate the burden on affected individuals and healthcare systems[12,13].

A study conducted in Bangladesh found that while participants showed improvements in psychological and social domains of HRQoL over a year after contracting from COVID-19, physical health scores remained lower than pre-infection levels, indicating ongoing challenges for many survivors[14]. Similarly, a cross-sectional analysis in Italy revealed that factors such as gender, age, and disease severity significantly influenced HRQoL outcomes in long-term post COVID health implications with females and older adults reporting significantly poorer quality of life and the impact was more pronounced among those with severe disease[15].

These findings emphasize the necessity for comprehensive assessments of HRQoL in post-COVID-19 patients to identify specific needs and tailor interventions effectively. By addressing the multidimensional impacts of COVID-19 on health and well-being, healthcare providers can better support recovery and improve the overall quality of life for affected individuals.

Comparative studies have reported international variation in post-COVID HRQoL, with evidence from Italy and Belgium highlighting differences in symptom persistence and recovery trajectories. For example, a systematic review revealed that post-COVID-19 patients in countries such as Italy and Belgium experienced lower HRQoL scores compared to individuals who had not been infected with COVID-19, with notable impairments in both physical and mental health domains[16,17].

India's vast and demographically diverse population presents unique challenges in understanding and addressing the long-term consequences of COVID-19. Socioeconomic disparities, variations in healthcare access, and differences in population health profiles necessitate a comprehensive examination of HRQoL and long-term health outcomes in people with a history of COVID-19 across the country[18,19]. Existing studies have primarily concentrated on short-term out

However, only a limited number of studies from India have specifically examined post-COVID HRQoL, underscoring a major evidence gap. This systematic review and meta-analysis (SRMA) synthesize the current evidence on HRQoL and long-term health outcomes among people with a history of COVID-19 in India. By consolidating data from various studies, we aim to provide a nuanced understanding of the chronic manifestations of COVID-19 and their implications for public health and clinical practice.

The SRMA were carried out in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines[23]. This SRMA were prospectively designed and registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews under registration number of CRD42024511990.

A comprehensive and systematic literature search was conducted across five major electronic databases: PubMed, EMBASE, DOAJ, Google Scholar, and ProQuest, to identify studies evaluating HRQoL in post-COVID-19 patients from India. The search encompassed peer-reviewed publications from January 2020 to April 2024, and was designed to capture both general and India-specific literature.

The search strategy combined Medical Subject Headings and free-text keywords tailored to each database. Core search terms included: (1) “COVID-19” OR “SARS-CoV-2”; (2) “Health-related quality of life” OR “HRQoL”; (3) “Post-recovery”; (4) “Long COVID” OR “post-COVID syndrome”; and (5) “India”. Boolean operators such as “AND” and “OR” were applied to maximize coverage. Additional modifiers such as “Indian patients”, “South Asia”, and “India-specific” were included to ensure relevance to the target population (Table 1).

| Concept | Medical Subject Headings terms | Synonyms |

| COVID-19 | COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, coronavirus | 2019-nCoV, novel coronavirus, COVID |

| Health-Related Quality of Life | Health-related quality of life, HRQoL, quality of life, well-being | Patient-reported outcomes, life quality, wellness, health status |

| Post-COVID Recovery | Post-recovery, post-acute sequelae, long COVID, post-COVID syndrome | COVID-19 recovery, post-acute COVID, chronic COVID syndrome |

| India | India, Indian patients, South Asia | Indian population, India-specific |

| Measurement tools | SF-36, EuroQol 5-Dimensional questionnaire, PROMIS, WHOQOL, HRQoL instruments | Health-related quality of life scales, health surveys, patient-reported outcome measures |

The search was restricted to English-language, peer-reviewed articles that explicitly focused on Indian populations or presented disaggregated data relevant to India. Reference lists of the included studies were manually screened to identify additional eligible studies not captured through the initial search. Grey literature and regional repositories, including the Indian Citation Index, were also explored to enhance comprehensiveness.

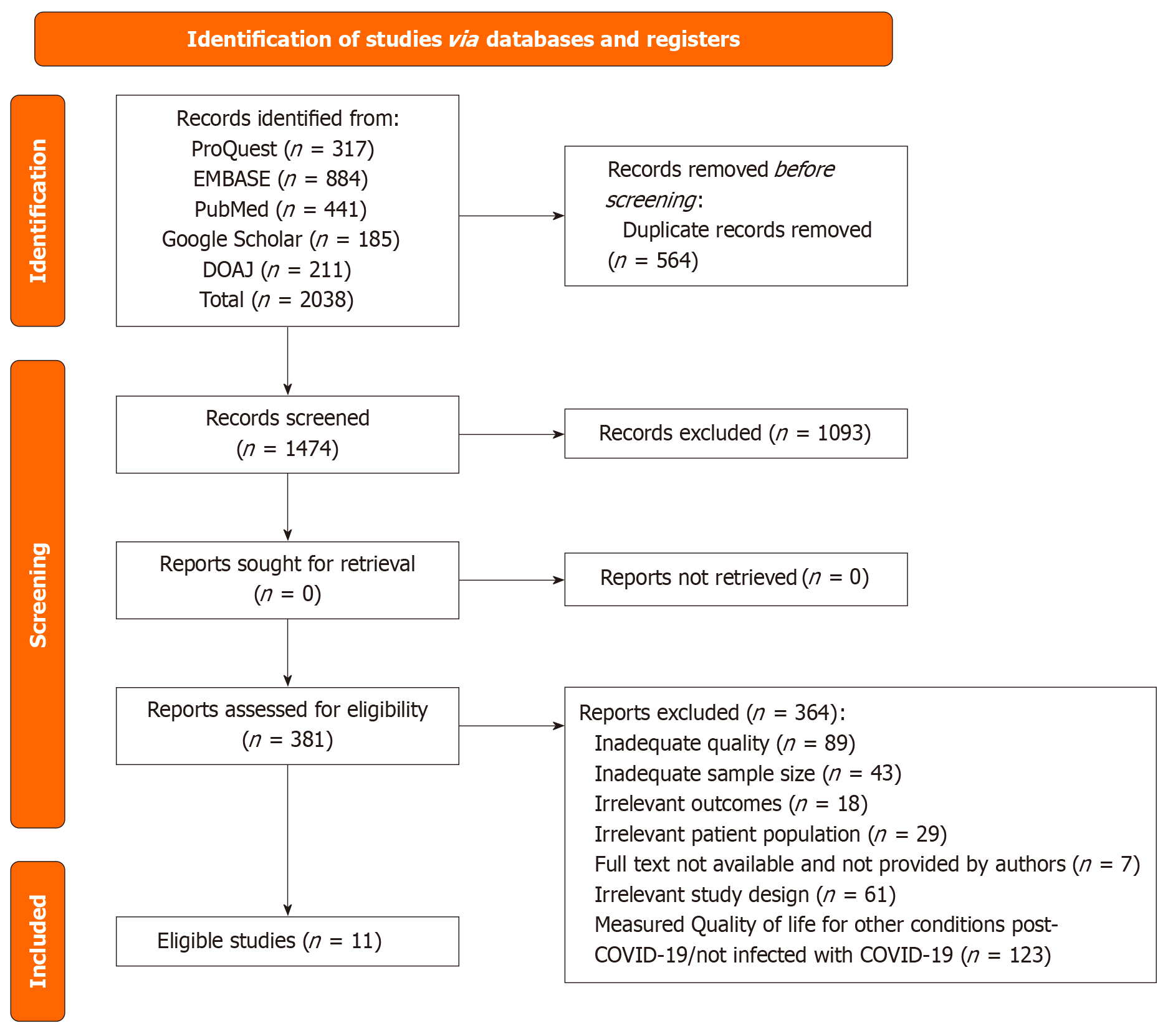

The study selection procedure was structured according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses standards[24]. After importing all search results into a reference management software, 564 duplicate records were removed, leaving 1474 studies for initial screening. Titles and abstracts were independently screened by four reviewers. Articles that clearly failed to meet the inclusion criteria were excluded at this stage. Full texts of 381 potentially eligible studies were retrieved for in-depth assessment. Of these, 370 studies were excluded due to various reasons: (1) Inadequate methodological quality (n = 88); (2) Small sample size (n = 41); (3) Irrelevant outcomes (n = 18); (4) Non-target populations (n = 31); (5) Inaccessible full texts (n = 7); (6) Inappropriate study design (n = 63); and (7) Focusing on quality of life unrelated to post-COVID-19 conditions (n = 120). Ultimately, 11 studies satisfied all inclusion criteria and were incorporated into the final analysis (Figure 1, Table 2). Disagreements during the selection and review stages were resolved through discussion and consensus among the reviewers.

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

| Population | Adults (≥ 18 years) with confirmed COVID-19 infection in India | Studies involving paediatric populations (< 18 years) |

| Focus area | Studies specifically assessing HRQoL post-COVID-19 in Indian patients | Studies focusing on other regions or populations outside of India |

| Outcome | HRQoL assessed using validated/standardized instruments (e.g., Short Form-36 Health Survey, EuroQol 5-Dimensional questionnaire, Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System) | Studies without HRQoL outcomes or using non-validated HRQoL measures |

| Study design | Observational, longitudinal, cohort, and cross-sectional studies | Case reports, editorials, reviews, and non-peer-reviewed sources |

| Language | Studies published in English | Studies published in languages other than English |

| Time period | Studies published from 2020 to 2024 | Studies published outside the specified time frame |

| COVID-19 specificity | Studies focused on patients’ post-COVID-19 recovery (including post-acute sequelae) | Studies involving other infectious diseases or comorbid conditions unrelated to COVID-19 |

Data were independently extracted by two authors using a standardized template. Extracted information included: (1) Study identifiers (author, year, setting); (2) Study design and sample size; (3) Participant demographics (age, gender); (4) COVID-19-specific variables [disease severity, hospitalization or intensive care unit (ICU) status, recovery duration]; and (5) HRQoL measures (tools used, domains assessed, utility scores). Any discrepancies in data extraction were resolved by consensus.

A narrative synthesis of the included studies was conducted to describe the HRQoL profiles of post-COVID-19 patients in India. The extracted data were summarized in tabular form (Table 3)[25-35].

| Ref. | Region | Study design | Sample size | HRQoL assessment tool | Type of comorbidities measured in the sample population | Duration of study | Age (in years) | Male | Female | Findings |

| Barani et al[30], 2022 | Tamil Nadu | Cross sectional study | 372 | EQ-5D-5 L | DM, HTN, CVD, CKD, RD, Cancer | 2 months (from November 2020 to December 2020) | 44.5 ± 15.3 | 57.5% | 42.5% | The mean EQ-5D utility score was 0.925 ± 0.150, and the mean EQ-VAS was 90.68 ± 11.81. Men had a higher utility value than women. Those with comorbidities and longer hospital stays had lower utility scores |

| Christopher et al[34], 2024 | Vellore, Tamil Nadu | Cross-sectional study | 207 | SGRQ | DM, HTN, Ischemic heart disease, RD, CKD, Cancer | 6 months (from August 2020 to January 2021) | 48.7 ± 14.2 | 68.1% | 31.9% | The COVID-19 pneumonia group when compared to the mild COVID-19 group had a greater mean total SGRQ score (29.2 vs 11.0; P < 0.0001). It was found that post-COVID-19 lung damage leads to significant impairment of lung function, and quality of life |

| Elumalai et al[35], 2023 | Tamil Nadu | Cross-sectional study | 1047 | EQ-5D-5 L | DM, HTN, CVD, RD, Thyroid | 7 months (from June 2020 to January 2021) | 38 (29-51) | 68% | 32% | The mean EQ-5D-5 L utility score was 0.98 ± 0.05 and EQ-VAS was 92.14 ± 0.39. The symptomatic group, older age group, female gender and those with comorbidity had persistent symptoms, had relatively low utility score for HRQoL |

| Gupta et al[32], 2022 | Kota, Rajasthan, India | Cross-sectional, semi-structured and questionnaire-based study | 173 | EQ-5D-5 L | Anemia, pre-eclampsia, antepartum eclampsia, hypothyroidism | 4 months (from March 2021 to June 2021) | 26.3 ± 6.6 | - | 100% | Post-COVID, 82.56% were asymptomatic, while 1744% had symptoms. Using EQ-5D-5 L, most reported no problems in any dimension, with some issues in mobility (3.46%), usual activities (5.2%), pain/discomfort (7.52%), and anxiety/depression (8.1%). Anxiety/depression reached level 2 in 1.73% of subjects |

| Hegde et al[27], 2022 | Karnataka, India | Retrospective observational study | 118 | EQ-5D-5 L | - | 7 months (from June 2020 to December 2020) | 45.28 ± 17.76 | 58.5% | 41.5% | Anxiety/depression scores changed significantly over time (at discharge, 4 weeks, and 8 weeks). Scores improved notably between discharge and 8 weeks. At 4 weeks, age was linked to higher anxiety/depression. Overall health index scores also showed significant differences across the three time points |

| Jain et al[29], 2023 | Jhansi | Multicentric cross sectional | 491 | EUROHIS-QOL 8, GAD-7, and MDI | - | 3 months (from July 2020 to September 2020) | 52.23 ± 7.31 | 62% | 38% | The mean EUROHIS-QOL score was found to be 328 ± 0.98. New-onset psychological disorders and sleep disturbances were observed in severe COVID-19 survivors. Long term quality of life and work ability remained poor for survivors who had prolong ICU admission. GAD-7 Scale: The mean score was 18.63 ± 3.28, reflecting moderate to severe anxiety levels. MDI: The mean score was 4.12 ± 1.45, indicative of mild to moderate depressive symptoms |

| Neelima and Chivukula[31], 2023 | Andhra Pradesh | Cross-sectional study | 107 | EQ-5D-5 L | DM, HTN, asthma, thyroid | 5 months (from August 2022 to January 2023) | 55.24 ± 9.94 | 66.6% | 33.4% | The mean EQ-5D-5 L utility score was 0.51 ± 0.43 and EQ-VAS was 68.97 ± 22.27. Patients with comorbidities had lower EQ-5D-5 L scores. A significant negative correlation between ICU stay duration and EQ-5D-5 L score was noted. COVID-19 patients with comorbidities had a significantly poorer quality of life |

| Revathishree et al[25], 2022 | Thandalam, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India | Prospective cross-sectional study | 250 | FCV-19S (fear/anxiety of COVID-19 individuals) | DM, HTN, asthma, thyroid, CAD | 1 month (from June 1, 2020 to June 30, 2020) | 41.13 ± 9.93 | 70.8% | 29.2% | High the clinical category score, higher FCV-19S. Post treatment score suggested COVID-19 survivors had a definite improvement in their quality of life, but still had mental stress even after full recovery. Survivors also faced social discrimination |

| Sarda et al[33], 2022 | Delhi | Cross-sectional study | 251 | Fatigue Severity Scale, WHOQOL-BREF | Musculoskeletal disorders, RD, fatigue, GID, ND, SD | 3 month (from May 2020 to July 2020) | 35.8 ± 12.5 | 67.3% | 32.7% | Long COVID-19 patients showed higher fatigue severity and lower WHOQOL-BREF scores than those without, with males having higher WHOQOL-BREF scores than females, and a negative correlation between WHOQOL-BREF scores and symptom duration |

| Shah et al[26], 2023 | Unclear | Prospective cross-sectional study | 388 | EQ-5D-3 L scale | DM, HTN, CVD, Thrombosis | 5 months (from February 2021 to June 2021) | 48 (36-59) | 62.6% | 37.4% | EQ-5D-3 L showed significant improvement in quality of life at 3 months compared to 1 month, especially in non-ICU patients. The mean EQ-VAS score also improved at 3 months. Illness severity correlated with quality of life. The study showed ongoing improvement in quality of life |

| Wasim and Kuriakose[28], 2024 | Bangaluru, Karnataka | Observational study | 264 | Short Form-36 Health Survey (RAND 36-Item Health Survey Instrument) questionnaire | Not reported | - | 22.37 ± 3.11 | 44% | 56% | Long COVID symptoms were found in 43.2% of subjects. The duration of symptoms ranged from less than one month (46.6%) to more than five months (10.2%). In the quality of life, mental health was the most affected domain. The overall averages for the physical component were 7111 ± 8.24 and 64.20 ± 10.73 for the mental component |

Continuous HRQoL scores were extracted from all eligible studies; however, due to substantial variation in mea

All other HRQoL instruments [EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale (EQ-VAS), Short Form-36 Health Survey (SF-36), World Health Organization Quality of Life-Brief Version (WHOQOL-BREF), European Health Interview Survey-Quality of Life (EUROHIS-QOL)] were not pooled quantitatively because of heterogeneity in scoring systems.

For binary outcomes, effect estimates and their 95%CI. Determinants included age (≥ 60 years), sex, vaccination status, comorbidity (≥ 1 chronic condition), and indicators of disease severity (e.g., ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, abnormal pulmonary function). We performed random-effects meta-analyses using the inverse-variance method to pool log-transformed odds ratios (ORs). When a study reported more than one HRQoL-related OR for the same determinant [e.g., multiple EuroQol 5-Dimensional questionnaire (EQ-5D) domains], domain-specific log(OR) values were combined using inverse-variance weighting to generate a single study-level estimate and avoid double counting. Heterogeneity was assessed using τ2 and I2 statistics.

Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic and interpreted according to Cochrane recommendations, with I2 > 50% indicating substantial heterogeneity. τ2 values were computed to quantify between-study variance. Funnel plots were visually inspected to assess publication bias; Egger’s test was performed when at least ten studies were available. All analyses were conducted using R under a random-effects framework to generate conservative, generalizable effect estimates.

The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed. Two authors utilised JBI critical evaluation techniques to independently assess the methodological quality and risk of bias in included research[36]. A third author resolved potential disagreements. We rated research based on their JBI ratings and classified them as low, moderate, or high risk of bias[36].

A total of 11 studies, comprising more than 3600 participants, were retained in the systematic review and included in the meta-analysis. Nine studies contributed extractable mean and standard deviation values for pooled analysis of HRQoL, while additional studies were included in subgroup analyses of predictors. The study sample sizes ranged from 107 participants to 1047 participants (Table 3) while the study duration in the different studies varied from one month to seven months post-discharge[25-35].

Table 3 summarizes the selected studies that assessed HRQoL following COVID-19[25-35]. Among these, eight were cross-sectional observational studies, including one multicentric study, with sample sizes ranging from 107 participants to 1047 participants. Two studies adopted a prospective follow-up observational design, with sample sizes of 250 and 388 participants[25,26]. One retrospective observational study included 118 participants, while another community-based cross-sectional study focused on 264 participants[27,28]. Collectively, these studies contribute to understanding HRQoL variations in diverse populations, with sample sizes ranging from 107 participants to 1047 participants.

Across the 11 included studies, a range of instruments were employed to assess HRQoL. The most widely applied tools were the EQ-5D-5 L used in 4 studies and the EQ-VAS in 2 studies. Other validated scales included the SF-36 in 1 study, WHOQOL-BREF in 1 study, EUROHIS-QOL in 1 study, and the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ) in 1 study. Additional domain-specific instruments were also used, such as the Fatigue Severity Scale in 1 study and the Fear of COVID-19 Scale (FCV-19S) in 1 study. While all instruments assessed multiple domains of HRQoL, the EQ-5D-5 L and EQ-VAS were the most consistently applied (Table 3)[25-35].

Ten studies across different Indian states reported varied impacts of COVID-19 on HRQoL. Comorbidities, prolonged hospital stays, older age, and female sex were consistently associated with lower EQ-5D utility scores and poorer outcomes. Several studies noted psychological disorders, fatigue, anxiety, and social stigma as persistent challenges, while others observed gradual improvements in mental health and quality of life over time. Severe disease and ICU admission were negatively correlated with HRQoL, whereas male participants generally reported higher scores. The prevalence of long COVID symptoms ranged from 17% to 43%, with mental health domains being particularly affected. These findings highlight the multifactorial determinants of post-COVID HRQoL in India, effected by demographic, clinical, and regional factors. The detailed sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are reported in Table 3[25-35].

The studies presented in Table 3 shows disparities in HRQoL outcomes stratified by gender and age among COVID-19 patients in India[25-35]. Male participants were overrepresented in most studies, accounting for a higher percentage of the sample populations, ranging from 57.5% to 70.8%, like Barani et al[30], where men had a higher EQ-5D-5 L utility score than women. Regarding age, younger patients generally showed better HRQoL outcomes compared to older adults. For example, in Neelima and Chivukula[31] which had a relatively higher mean age (55.24 years), HRQoL scores were notably lower, with a mean EQ-5D-5 L utility score of 0.51. In contrast, studies involving younger populations, such as Gupta et al[32] with a mean age of 26.3 years, showed higher HRQoL outcomes, with over 90% of participants reporting normal HRQoL dimensions like mobility and self-care. Additionally, older age was associated with persistent symptoms and slower HRQoL recovery in studies such as Hegde et al[27], where anxiety and depression scores were particularly high among older participants. Age emerged as a key factor, with older adults consistently reporting lower utility scores and delayed recovery. These findings suggest that older age, particularly beyond 50 years, is associated with greater deterioration in HRQoL, with comorbidities, disease severity, and female sex acting as additional determinants. Recovery duration varied, with studies such as Shah et al[26] noting improved EQ-VAS scores from one to three months post-discharge. Moreover, long COVID symptoms – particularly fatigue, breathlessness, and psychological distress – were prevalent and contributed to lower HRQoL, as highlighted by Wasim and Kuriakose[28], Sarda et al[33], and Christopher et al[34].

The spectrum of HRQoL outcomes reported in the selected studies. Considerable methodological heterogeneity was observed due to the use of different HRQoL assessment tools and scales. In the survey conducted by Barani et al[30], a mean ± SD EQ-5D-5 L utility score of 0.925 ± 0.150 (range from 0 to 1) and an EQ-VAS score of 90.68 ± 11.81 (ranges from 0 to 100) were reported that indicated strong recovery among the COVID patients. Similarly, a mean EQ-5D-5 L utility score of 0.98 ± 0.05 and an EQ-VAS score of 92.14 ± 0.39 were reported in the study conducted by Elumalai et al[35], indicating good recovery. In contrast, the survey conducted by Neelima and Chivukula[31] reported a low HRQoL mean utility score of 0.51 ± 0.43 and an EQ-VAS score of 68.97 ± 22.27, which was indicative of possible impairments post-recovery. In another study, Christopher et al[34] used the SGRQ (0-100, higher scores indicating worse respiratory health) and discovered that 41.0% of participants reported having persistent respiratory symptoms with SGRQ scores ≥ 25.90%. Using the EQ-5D-5 L, Gupta et al[32] found that over 90% of participants did not report any problems with mobility, self-care, or usual activities other than a few minor issues in mobility (3.46%), pain/discomfort (7.52%), and usual activities (5.2%). Hegde et al[27] used the EuroQol-5D-5 L to assess HRQOL scores at three-time points: At discharge, 4 weeks, and 8 weeks post-discharge. Mobility issues decreased from 9.8% at discharge to 4.9% at 8 weeks. Similarly, self-care pro

The most common comorbidities reported in the included studies were diabetes mellitus and hypertension (HTN) with prevalence estimates of diabetes mellitus ranging from 3.09% to 52.3%, and for HTN were 9.8% to 39%. Less common, comorbidities include chronic kidney disease (CKD), cancer, ischemic heart disease, and musculoskeletal disorders. CKD prevalence was reported at 6.5% by Neelima and Chivukula[31] and 1.9% by Christopher et al[34], while cancer appeared with rates of 0.3% in Barani et al[30] and 4.3% in Christopher et al[34]. Additionally, ischemic heart disease was identified at a prevalence of 8.2% in Christopher et al[34]. These lower frequencies suggest that while these conditions are less common than diabetes and HTN, they still represent significant health risks for COVID-19 patients.

Certain comorbidities appeared distinctly in specific studies, such as anaemia, pre-eclampsia, and antepartum eclampsia, which were exclusively reported by Gupta et al[32] with prevalence rates of 7.5%, 6.35%, and 3.47%, respectively. Similarly, thrombosis, with a low occurrence rate of 0.25%, was only noted in the study by Shah et al[26] (Supplementary material).

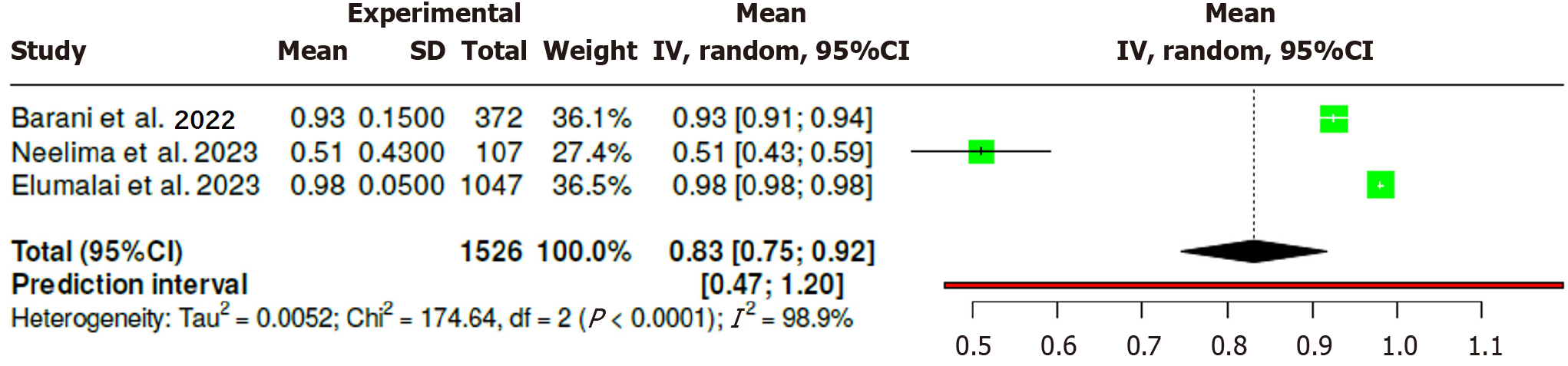

Three studies (n = 1526) reported EQ-5D utility scores. The pooled utility was 0.83 (95%CI: 0.75-0.92); however, heterogeneity was high (I2 = 98.9%), reflecting substantial differences in study populations. Elumalai et al[35] reported near-normal utility among mostly mild and moderate cases (0.98), Barani et al[30] showed moderately reduced utility (0.93), whereas Neelima et al[31] documented markedly impaired HRQoL among ICU survivors (0.51) (Figure 2).

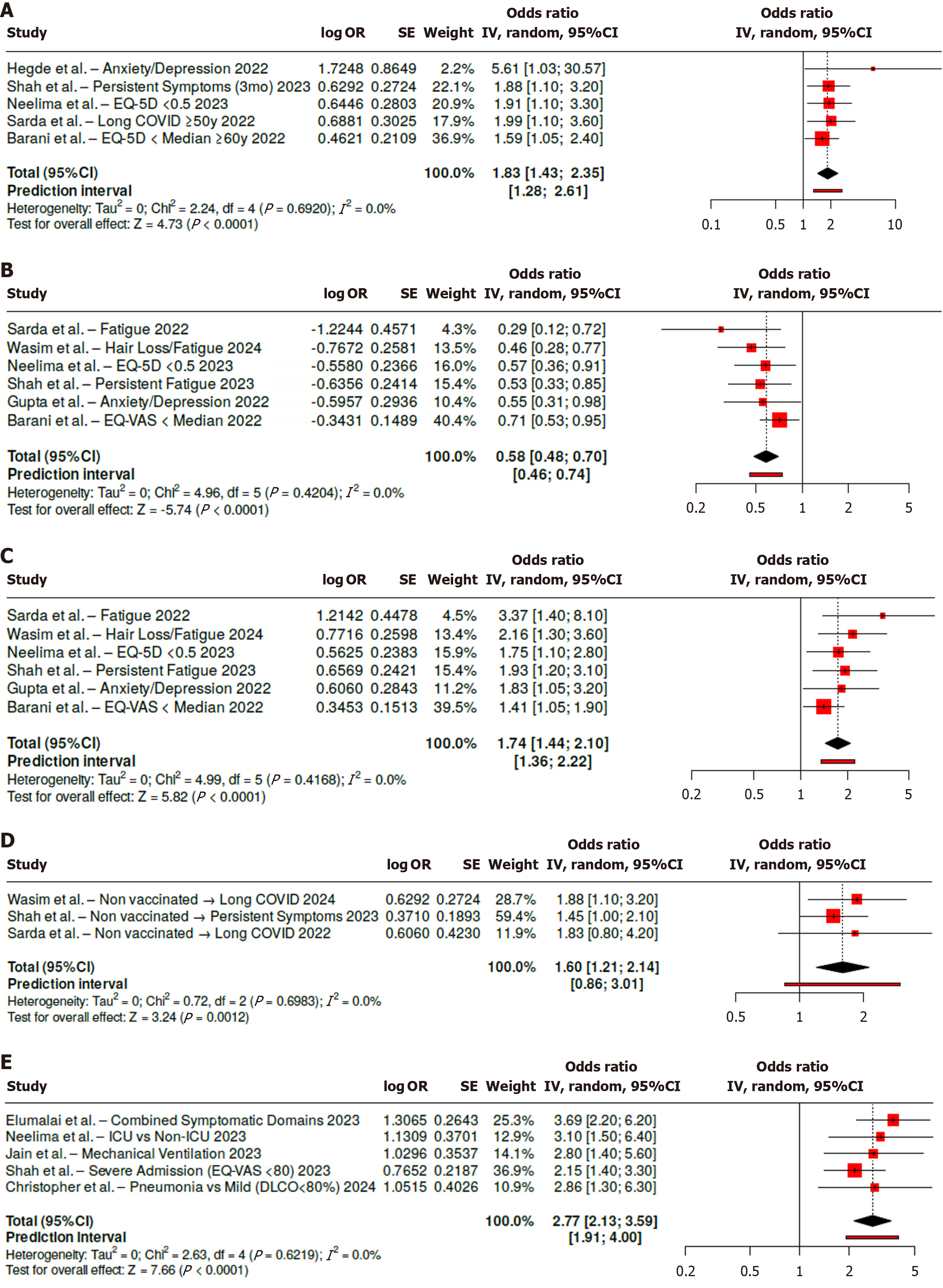

Age emerged as another key determinant. Participants aged ≥ 60 years had approximately twice the odds of persistent symptoms or reduced EQ-5D utility scores (pooled OR = 1.83, 95%CI: 1.43-2.35; I2 = 0%) (Figure 3A)[26,27,30,31,33]. Sex-stratified analyses revealed an explicit gender disparity: Females were more than twice as likely to experience impaired HRQoL (pooled OR = 1.74, 95%CI: 1.44-2.10; I2 < 30%), whereas males had a significantly lower risk (pooled OR = 0.58, 95%CI: 0.48-0.70), indicating a protective effect (Figure 3B and C)[26,28,30-33].

Vaccination status was also a significant predictor of outcomes. Across three studies, being unvaccinated was associated with 60% higher odds of lower HRQoL in long COVID (pooled OR = 1.60, 95%CI: 1.21-2.14; I2 = 0%), under

Several consistent determinants of impaired HRQoL were identified. Comorbidity was strongly associated with poor HRQoL, with a nearly two-fold higher risk compared with those without chronic conditions (pooled OR = 1.94, 95%CI: 1.43-2.63; I2 = 0%). Disease severity demonstrated stronger effect: Across five studies, severe COVID-19 or ICU admission nearly tripled the odds of poor HRQoL (pooled OR = 2.77, 95%CI: 2.13-3.59; I2 = 0%), with highly consistent findings (Figure 3E)[26,29,31,34,35].

The quality of the studies was assessed using the JBI Critical Appraisal tool[36] with most studies receiving a rating of "good". A total of 10 (90.9%) studies met all eight quality criteria, including clearly defined sample inclusion, detailed subject descriptions, reliable measurement of exposure and outcomes, and appropriate statistical analysis (Supple

This systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrate that COVID-19 has a substantial and lasting impact on HRQoL among people with a history of COVID-19 in India. The evidence consistently shows deterioration across physical, psychological, and social domains, particularly among individuals with advanced age, comorbidities, severe acute illness, or intensive care admission. Female participants were more likely to experience impaired HRQoL, while male sex appeared protective. Unvaccinated individuals also demonstrated worse recovery outcomes, underscoring the role of preventive measures.

The use of diverse but validated instruments including EQ-5D-5 L, EQ-VAS, SF-36, WHOQOL-BREF, and EUROHIS-QOL – adds strength to these findings by capturing multidimensional aspects of post-COVID well-being. Despite differences in tools and follow-up periods, a consistent pattern emerged: Patients with pre-existing conditions such as diabetes, HTN, and CKD, as well as those experiencing long-term fatigue, psychological stress, or social stigma, reported markedly lower HRQoL.

Extensive global research strongly corroborates these findings, indicating that the HRQoL repercussions of COVID-19 represent a significant and enduring challenge[37,38]. A study from Bangladesh observed that the participant’s physical health scores remained significantly lower than pre-infection levels even 12 months post-recovery[14]. Those who experienced severe COVID-19 or had pre-existing conditions faced considerable physical health limitations, particularly regarding mobility and daily activities, even 12 months after recovery[14]. This observation aligns with the current study's findings, which also indicate that in India, recovery of physical health and overall HRQoL is delayed by 25 days, ranges from 16 days to 34 days, particularly among individuals with chronic conditions whereas long COVID patients reported a median recovery time of approximately 7.9 months[39].

Similar findings have been reported in Europe, where research has examined the long-term effects of COVID-19 on quality of life across various health domains. Pooled results from Italian studies indicated that older adults, women, and patients with severe COVID-19 outcomes experienced poorer HRQoL, particularly in mental health and social interaction areas[16]. Individuals with more severe COVID-19 symptoms requiring hospitalization or intensive care had significantly lower HRQoL scores, emphasizing the correlation between disease severity and reduced post-recovery quality of life. Another national study from Italy based on analysis of death certificates, observed that COVID-19 was the underlying cause of death in 46.0% of cases associated with post-COVID conditions (n = 4752)[40].

The impact of comorbidities on HRQoL among people with a history of COVID-19 has also been investigated in other global contexts. A study conducted in Brazil a nationwide cross-sectional study found that comorbidities such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and obesity were significant predictors of decreased HRQoL following COVID-19[41]. Similar findings were observed in this review wherein patients with chronic diseases experienced inferior HRQoL during recovery post-COVID-19 since the pre-existing conditions exacerbated both physical and psychological symptoms associated with long COVID. The chronic conditions particularly diabetes and HTN often involve underlying immune system dysregulation, which is further accentuated by COVID-19, leading to prolonged inflammation and delayed recovery. Additionally, endothelial dysfunction, a common factor in both COVID-19 and chronic diseases, impairs vascular health and reduces oxygen delivery to tissues, contributing to persistent fatigue and diminished physical well-being[42]. Metabolic imbalances, frequently observed in conditions like diabetes, are also worsened by COVID-19, dis

Furthermore, gender-specific differences in HRQoL post-COVID-19 have been identified across various studies worldwide, with female patients often reporting lower quality of life reflected in higher levels of persistent fatigue, anxiety, and depressive symptoms compared to males[44,45]. A Prospective study conducted in India involving long COVID patients revealed that women's HRQoL scores, particularly in mental health and social domains were significantly lower than those of men, likely due to the additional psychological burdens and societal roles typically assumed by women[46]. Evidence from this systematic review including Indian studies also suggests that female patients tend to report higher burden of poorer mental health and increased anxiety compared to male patients. Although male participants were overrepresented in most included studies and generally reported higher HRQoL scores, the smaller proportion of female participants consistently demonstrated poorer outcomes, indicating a disproportionate burden of long-COVID among women.

The global studies on the social and psychological repercussions of COVID-19 indicated a widespread sense of isolation, stigma, and anxiety among survivors especially in the initial months after the pandemic[47-49]. A UK study emphasized the psychological toll on those affected by COVID-19, particularly among ethnic minorities who frequently encounter additional social discrimination and reduced access to quality healthcare services[50]. Similarly, this review found that studies employing the FCV-19S reported elevated levels of anxiety and psychological stress among those with a history of COVID-19 in India, some of whom also experienced social discrimination[25,33]. Addressing these psychological and social challenges is essential as they can impede recovery and intensify long-term mental health issues for survivors, especially in resource-limited settings.

Given the global consistency in challenges associated with long COVID, evidence strongly indicates that a multidisciplinary, patient-centred approach to post-COVID rehabilitation is crucial. Health systems worldwide are beginning to establish comprehensive post-COVID clinics and multidisciplinary rehabilitation programs that address physical, psychological, and social needs. For instance, Spain has launched a nationwide initiative offering tailored care for long COVID patients that includes physical rehabilitation, psychological counselling, and support for managing chronic comorbidities[51]. This model has shown promising results with improved HRQoL outcomes reported among participating patients. Implementing similar programs in India could prove highly beneficial due to the diverse range of post-COVID symptoms necessitating a holistic approach to care[52]. In addition to demographic and clinical determinants, post-COVID pulmonary sequelae such as lung fibrosis, reported in approximately 7% of survivors, represent an important factor that may further compromise HRQoL. The absence of high-resolution computed tomography-based assessment in most included studies limits our ability to directly evaluate this association, but it remains a critical area for future research. Specifically, targeted rehabilitation services for high-risk groups including older adults, women, and individuals with comorbidities – could help bridge gaps in long-term recovery from COVID-19.

This study offers several strengths that enhance its contributions to understanding the long-term impacts of COVID-19 on HRQoL. Firstly, it employed a comprehensive data collection approach using a variety of validated HRQoL assessment tools, such as the EQ-5D-5 L, SF-36, and WHOQOL-BREF, which allowed for a robust analysis of different dimensions of HRQoL among people with a history of COVID-19. The inclusion of a diverse patient population from various demo

The study acknowledges certain limitations. Interpretation of the pooled EQ-5D utility score requires caution due to the limited number of included studies (n = 3). Given the significant clinical diversity among these populations, the random-effects pooling serves primarily as a descriptive summary rather than a reliable prediction of the true post-COVID utility distribution. The sample size was limited in certain subgroups, potentially affecting the statistical power and generalizability of the results. The reliance on self-reported measures may introduce bias due to subjective interpretations of health status, with participants possibly overestimating or underestimating their symptoms. The findings may also be influenced by regional healthcare disparities and cultural factors specific to India, which might not be applicable to other contexts or countries. It is estimated that 7% of patients with COVID-19 develop persistent lung fibrosis[53]. However, the evaluation of COVID-19 related lung fibrosis in patients with respiratory symptoms using high-resolution computed tomography was not assessed in any of the studies which precluded assessment of this condition which is known to severely compromise HRQoL.

This systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrate that post-COVID HRQoL is suboptimal among people with a history of COVID-19 in India. Recovery outcomes are influenced by multiple determinants, with older age, female sex, comorbidities, severe disease, and lack of vaccination consistently associated with poorer HRQoL due to persistent impairment. These findings highlight the disproportionate burden faced by vulnerable groups and underscore the need for targeted interventions, including long-term follow-up, rehabilitation services, and integration of mental health support into post-COVID care. From a public health perspective, the evidence reinforces the importance of vaccination and proactive chronic disease management in mitigating the long-term consequences of COVID-19 in India.

| 1. | Cascella M, Rajnik M, Aleem A, Dulebohn SC, Di Napoli R. Features, Evaluation, and Treatment of Coronavirus (COVID-19). 2023 Aug 18. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan. [PubMed] |

| 2. | World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Post COVID-19 condition. 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/coronavirus-disease-(covid-19)-post-covid-19-condition. |

| 3. | World Health Organization. Post COVID-19 condition (Long COVID). 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/post-covid-19-condition. |

| 4. | Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government of India. National Comprehensive Guidelines for Management of Post-COVID Sequelae. Available from: https://covid19dashboard.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/NationalComprehensiveGuidelinesforManagementofPostCovidSequelae.pdf. |

| 5. | Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government of India. COVID-19 Statewise Status. Available from: https://covid19dashboard.mohfw.gov.in/. |

| 6. | Nalbandian A, Sehgal K, Gupta A, Madhavan MV, McGroder C, Stevens JS, Cook JR, Nordvig AS, Shalev D, Sehrawat TS, Ahluwalia N, Bikdeli B, Dietz D, Der-Nigoghossian C, Liyanage-Don N, Rosner GF, Bernstein EJ, Mohan S, Beckley AA, Seres DS, Choueiri TK, Uriel N, Ausiello JC, Accili D, Freedberg DE, Baldwin M, Schwartz A, Brodie D, Garcia CK, Elkind MSV, Connors JM, Bilezikian JP, Landry DW, Wan EY. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome. Nat Med. 2021;27:601-615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3262] [Cited by in RCA: 3161] [Article Influence: 632.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Long COVID Basics. 2025. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/covid/long-term-effects/index.html. |

| 8. | Cesnales NI, Thyer BA. Health-Related Quality of Life Measures. In: Michalos AC, editor. Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 2014: 2809-2814. |

| 9. | De Luca R, Bonanno M, Calabrò RS. Psychological and Cognitive Effects of Long COVID: A Narrative Review Focusing on the Assessment and Rehabilitative Approach. J Clin Med. 2022;11:6554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sapna F, Deepa F, Sakshi F, Sonam F, Kiran F, Perkash RS, Bendari A, Kumar A, Rizvi Y, Suraksha F, Varrassi G. Unveiling the Mysteries of Long COVID Syndrome: Exploring the Distinct Tissue and Organ Pathologies Linked to Prolonged COVID-19 Symptoms. Cureus. 2023;15:e44588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Huerne K, Filion KB, Grad R, Ernst P, Gershon AS, Eisenberg MJ. Epidemiological and clinical perspectives of long COVID syndrome. Am J Med Open. 2023;9:100033. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Touyz RM, Boyd MOE, Guzik T, Padmanabhan S, McCallum L, Delles C, Mark PB, Petrie JR, Rios F, Montezano AC, Sykes R, Berry C. Cardiovascular and Renal Risk Factors and Complications Associated With COVID-19. CJC Open. 2021;3:1257-1272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Silva Andrade B, Siqueira S, de Assis Soares WR, de Souza Rangel F, Santos NO, Dos Santos Freitas A, Ribeiro da Silveira P, Tiwari S, Alzahrani KJ, Góes-Neto A, Azevedo V, Ghosh P, Barh D. Long-COVID and Post-COVID Health Complications: An Up-to-Date Review on Clinical Conditions and Their Possible Molecular Mechanisms. Viruses. 2021;13:700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 270] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 49.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hawlader MDH, Rashid MU, Khan MAS, Liza MM, Akter S, Hossain MA, Rahman T, Barsha SY, Shifat AA, Hossian M, Mishu TZ, Sagar SK, Manna RM, Ahmed N, Debu SSSD, Chowdhury I, Sabed S, Ahmed M, Borsha SA, Al Zafar F, Hyder S, Enam A, Babul H, Nur N, Haque MMA, Roy S, Tanvir Hassan KM, Rahman ML, Nabi MH, Dalal K. Quality of life of COVID-19 recovered patients: a 1-year follow-up study from Bangladesh. Infect Dis Poverty. 2023;12:79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Mastrorosa I, Del Duca G, Pinnetti C, Lorenzini P, Vergori A, Brita AC, Camici M, Mazzotta V, Baldini F, Chinello P, Mencarini P, Giancola ML, Abdeddaim A, Girardi E, Vaia F, Antinori A. What is the impact of post-COVID-19 syndrome on health-related quality of life and associated factors: a cross-sectional analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2023;21:28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Figueiredo EAB, Silva WT, Tsopanoglou SP, Vitorino DFM, Oliveira LFL, Silva KLS, Luz HDH, Ávila MR, Oliveira LFF, Lacerda ACR, Mendonça VA, Lima VP, Mediano MFF, Figueiredo PHS, Rocha MOC, Costa HS. The health-related quality of life in patients with post-COVID-19 after hospitalization: a systematic review. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2022;55:e0741. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Moens M, Duarte RV, De Smedt A, Putman K, Callens J, Billot M, Roulaud M, Rigoard P, Goudman L. Health-related quality of life in persons post-COVID-19 infection in comparison to normative controls and chronic pain patients. Front Public Health. 2022;10:991572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kapoor M, Nidhi Kaur K, Saeed S, Shannawaz M, Chandra A. Impact of COVID-19 on healthcare system in India: A systematic review. J Public Health Res. 2023;12:22799036231186349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Gopalan HS, Misra A. COVID-19 pandemic and challenges for socio-economic issues, healthcare and National Health Programs in India. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:757-759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Mohamadi E, Olyaeemanesh A, Takian A, Yaftian F, Kiani MM, Larijani B. Short and Long-term Impacts of COVID-19 Pandemic on Health Equity: A Comprehensive Review. Med J Islam Repub Iran. 2022;36:179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Daodu TB, Rugel EJ, Lear SA. Impact of Long COVID-19 on Health Outcomes Among Adults With Preexisting Cardiovascular Disease and Hypertension: A Systematic Review. CJC Open. 2024;6:939-950. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bourmistrova NW, Solomon T, Braude P, Strawbridge R, Carter B. Long-term effects of COVID-19 on mental health: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2022;299:118-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 53.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | PRISMA statement. Available from: https://www.prisma-statement.org. |

| 24. | Cochrane Collaboration. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Available from: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook. |

| 25. | Revathishree K, Shyam Sudhakar S, Indu R, Srinivasan K. Covid-19 Demographics from a Tertiary Care Center: Does It Depreciate Quality-of-Life? Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2022;74:2721-2728. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Shah C, Keerthi BY, Gali JH. An observational study on health-related quality of life and persistent symptoms in COVID-19 patients after hospitalization at a tertiary care centre. Lung India. 2023;40:12-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hegde S, Sreeram S, Bhat KR, Satish V, Shekar S, Babu M. Evaluation of post-COVID health status using the EuroQol-5D-5L scale. Pathog Glob Health. 2022;116:498-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Wasim M, Kuriakose S. Assessment of long COVID symptoms and post-COVID quality of life in youth. Int J Epidemiol Health Sci. 2024;5:1-12. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 29. | Jain A, Gupta P, Mittal AA, Sengar NS, Chaurasia R, Banoria N, Kankane A, Saxena A, Brijendra, Sharma M. Long-term quality of life and work ability among severe COVID-19 survivors: A multicenter study. Dialogues Health. 2023;2:100124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Barani S, Bhatnagar T, Natarajan M, Gayathri K, Sonekar HB, Sasidharan A, Selvavinayagam TS, Bagepally BS. Health-related quality of life among COVID-19 individuals: A cross-sectional study in Tamil Nadu, India. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2022;13:100943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Neelima M, Chivukula SK. Assessment of health-related quality of life and its determinants among COVID-19 intensive care unit survivors. J Family Med Prim Care. 2023;12:3319-3325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Gupta V, Sharma A, Sharma S, Sharma A. Post-COVID symptoms and health-related quality of life in extended postpartum period. Asian J Med Sci. 2022;13:14-18. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Sarda R, Kumar A, Chandra A, Bir M, Kumar S, Soneja M, Sinha S, Wig N. Prevalence of Long COVID-19 and its Impact on Quality of Life Among Outpatients With Mild COVID-19 Disease at Tertiary Care Center in North India. J Patient Exp. 2022;9:23743735221117358. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Christopher DJ, Isaac BTJ, John FB, Shankar D, Samuel P, Gupta R, Thangakunam B. Impact of post-COVID-19 lung damage on pulmonary function, exercise tolerance and quality of life in Indian subjects. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2024;4:e0002884. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Elumalai R, Bagepally BS, Ponnaiah M, Bhatnagar T, Barani S, Kannan P, Kantham L, Sathiyarajeswaran P, D S; Post COVID-19 study team. Health-related quality of life and associated factors among COVID-19 individuals managed with indian traditional medicine: A cross-sectional study from south India. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2023;20:101250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | JBI. JBI Critical Appraisal Tools. Available from: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools. |

| 37. | Arab-Zozani M, Hashemi F, Safari H, Yousefi M, Ameri H. Health-Related Quality of Life and its Associated Factors in COVID-19 Patients. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2020;11:296-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Soare IA, Ansari W, Nguyen JL, Mendes D, Ahmed W, Atkinson J, Scott A, Atwell JE, Longworth L, Becker F. Health-related quality of life in mild-to-moderate COVID-19 in the UK: a cross-sectional study from pre- to post-infection. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2024;22:12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Szewczyk W, Fitzpatrick AL, Fossou H, Gentile NL, Sotoodehnia N, Vora SB, West TE, Bertolli J, Cope JR, Lin JS, Unger ER, Vu QM. Long COVID and recovery from Long COVID: quality of life impairments and subjective cognitive decline at a median of 2 years after initial infection. BMC Infect Dis. 2024;24:1241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Grippo F, Minelli G, Crialesi R, Marchetti S, Pricci F, Onder G. Deaths related to post-COVID in Italy: a national study based on death certificates. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024;11:1401602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | de Oliveira JF, de Ávila RE, de Oliveira NR, da Cunha Severino Sampaio N, Botelho M, Gonçalves FA, Neto CJF, de Almeida Milagres AC, Gomes TCC, Pereira TL, de Souza RP, Molina I. Persistent symptoms, quality of life, and risk factors in long COVID: a cross-sectional study of hospitalized patients in Brazil. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;122:1044-1051. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Nägele MP, Haubner B, Tanner FC, Ruschitzka F, Flammer AJ. Endothelial dysfunction in COVID-19: Current findings and therapeutic implications. Atherosclerosis. 2020;314:58-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 33.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Li J, Zhou Y, Ma J, Zhang Q, Shao J, Liang S, Yu Y, Li W, Wang C. The long-term health outcomes, pathophysiological mechanisms and multidisciplinary management of long COVID. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 24.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Lakbar I, Luque-Paz D, Mege JL, Einav S, Leone M. COVID-19 gender susceptibility and outcomes: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0241827. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Barbieri V, Piccoliori G, Mahlknecht A, Plagg B, Ausserhofer D, Engl A, Wiedermann CJ. Adolescent Mental Health during the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Interplay of Age, Gender, and Mental Health Outcomes in Two Consecutive Cross-Sectional Surveys in Northern Italy. Behav Sci (Basel). 2023;13:643. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Bai F, Tomasoni D, Falcinella C, Barbanotti D, Castoldi R, Mulè G, Augello M, Mondatore D, Allegrini M, Cona A, Tesoro D, Tagliaferri G, Viganò O, Suardi E, Tincati C, Beringheli T, Varisco B, Battistini CL, Piscopo K, Vegni E, Tavelli A, Terzoni S, Marchetti G, Monforte AD. Female gender is associated with long COVID syndrome: a prospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022;28:611.e9-611.e16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 398] [Article Influence: 79.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Dubey S, Biswas P, Ghosh R, Chatterjee S, Dubey MJ, Chatterjee S, Lahiri D, Lavie CJ. Psychosocial impact of COVID-19. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14:779-788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1000] [Cited by in RCA: 969] [Article Influence: 161.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Mazza MG, De Lorenzo R, Conte C, Poletti S, Vai B, Bollettini I, Melloni EMT, Furlan R, Ciceri F, Rovere-Querini P; COVID-19 BioB Outpatient Clinic Study group, Benedetti F. Anxiety and depression in COVID-19 survivors: Role of inflammatory and clinical predictors. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;89:594-600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 967] [Cited by in RCA: 1065] [Article Influence: 177.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Thye AY, Law JW, Tan LT, Pusparajah P, Ser HL, Thurairajasingam S, Letchumanan V, Lee LH. Psychological Symptoms in COVID-19 Patients: Insights into Pathophysiology and Risk Factors of Long COVID-19. Biology (Basel). 2022;11:61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Proto E, Quintana-Domeque C. COVID-19 and mental health deterioration by ethnicity and gender in the UK. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0244419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 30.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Harenwall S, Heywood-Everett S, Henderson R, Godsell S, Jordan S, Moore A, Philpot U, Shepherd K, Smith J, Bland AR. Post-Covid-19 Syndrome: Improvements in Health-Related Quality of Life Following Psychology-Led Interdisciplinary Virtual Rehabilitation. J Prim Care Community Health. 2021;12:21501319211067674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Chaudhry D, Khandelwal S, Bahadur C, Daniels B, Bhattacharyya M, Gangakhedkar R, Desai S, Das J; Long COVID India study group. Prevalence of long COVID symptoms in Haryana, India: a cross-sectional follow-up study. Lancet Reg Health Southeast Asia. 2024;25:100395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Duong-Quy S, Vo-Pham-Minh T, Tran-Xuan Q, Huynh-Anh T, Vo-Van T, Vu-Tran-Thien Q, Nguyen-Nhu V. Post-COVID-19 Pulmonary Fibrosis: Facts-Challenges and Futures: A Narrative Review. Pulm Ther. 2023;9:295-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/