Published online Mar 25, 2024. doi: 10.5501/wjv.v13.i1.89104

Peer-review started: October 20, 2023

First decision: November 21, 2023

Revised: December 27, 2023

Accepted: January 24, 2024

Article in press: January 24, 2024

Published online: March 25, 2024

Processing time: 143 Days and 1.7 Hours

Reactivation of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a well-known risk that can occur spontaneously or following immunosuppressive therapies, including cancer chemotherapy. HBV reactivation can cause significant morbidity and even mortality, which are preventable if at-risk individuals are identified through screening and started on antiviral prophylaxis.

To determine the prevalence of chronic HBV (CHB) and occult HBV infection (OBI) among oncology and hematology-oncology patients undergoing chemo

In this observational study, the prevalence of CHB and OBI was assessed among patients receiving chemotherapy. Serological markers of HBV infection [hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)/anti-hepatitis B core antigen (HBc)] were evaluated for all patients. HBV DNA levels were assessed in those who tested negative for HBsAg but positive for total anti-HBc.

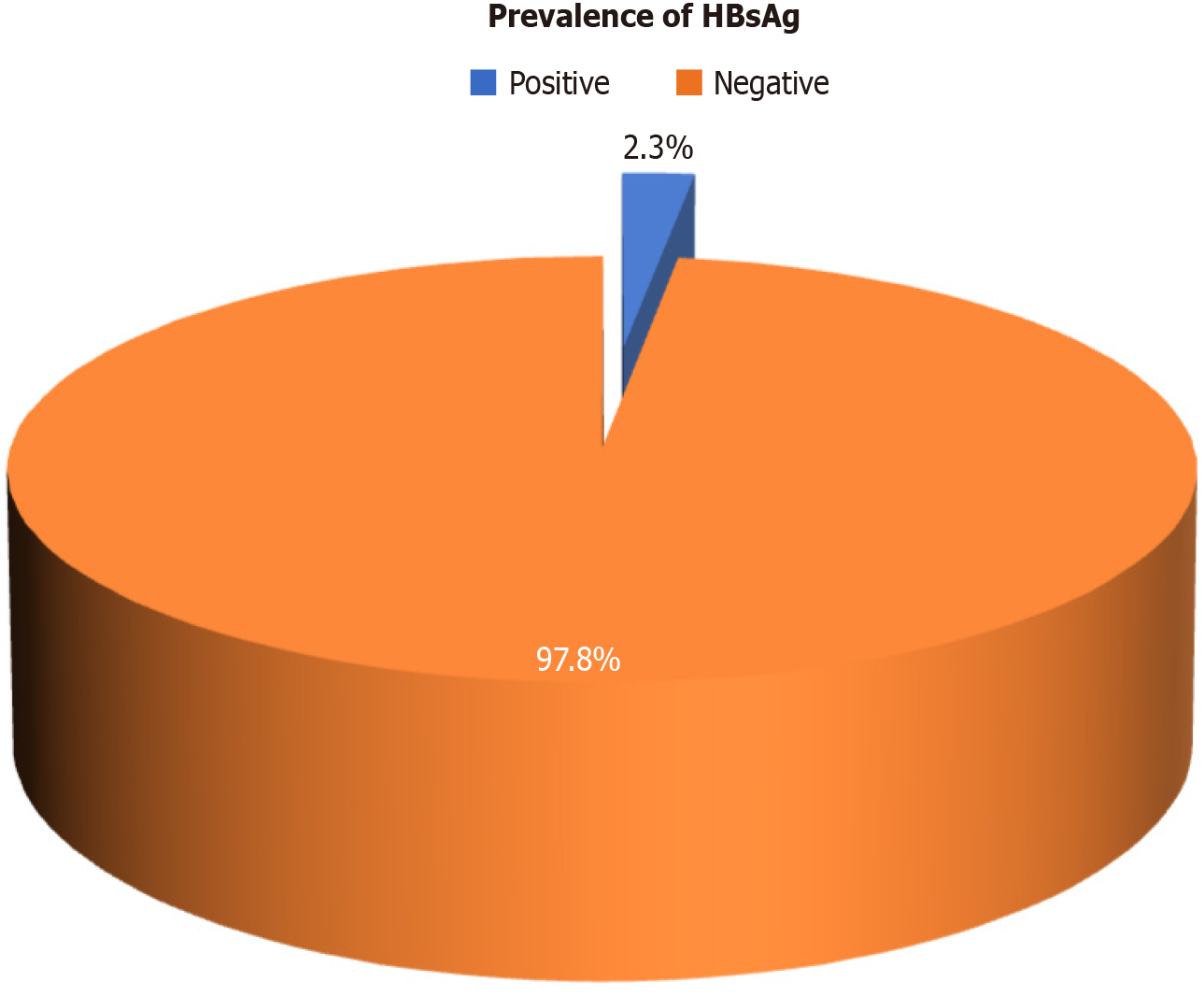

The prevalence of CHB in the study cohort was determined to be 2.3% [95% confidence interval (95%CI): 1.0-4.2]. Additionally, the prevalence of OBI among the study participants was found to be 0.8% (95%CI: 0.2-2.3).

The findings of this study highlight the importance of screening for hepatitis B infection in oncology and hematology-oncology patients undergoing chemotherapy. Identifying individuals with CHB and OBI is crucial for implementing appropriate antiviral prophylaxis to prevent the reactivation of HBV infection, which can lead to increased morbidity and mortality.

Core Tip: Hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation, a significant risk for individuals undergoing immunosuppressive therapy such as cancer chemotherapy, can lead to preventable morbidity and mortality. Our observational study determined the prevalence of chronic HBV (CHB) infection and occult HBV infection (OBI) in oncology and hematology-oncology patients receiving chemotherapy. Our results showed a 2.3% prevalence of CHB and 0.8% prevalence of OBI in our study cohort, underscoring the critical importance of routinely screening oncology and hematology-oncology patients for HBV infection. Identifying those with CHB and OBI is vital for promptly initiating antiviral prophylaxis, which can prevent the reactivation of HBV infection.

- Citation: Sudevan N, Manrai M, Tilak TVSVGK, Khurana H, Premdeep H. Chronic hepatitis B and occult infection in chemotherapy patients - evaluation in oncology and hemato-oncology settings: The CHOICE study. World J Virol 2024; 13(1): 89104

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3249/full/v13/i1/89104.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5501/wjv.v13.i1.89104

Reactivation of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a well-known risk that can occur spontaneously or following immunosuppressive therapies, including cancer chemotherapy[1]. This reactivation causes significant morbidity and mortality, which is preventable if at-risk individuals are identified through screening and started on antiviral prophylaxis[1]. The prevalence of chronic hepatitis B (CHB) infection and occult hepatitis B infection (OBI) among oncology and hemato-oncology patients receiving chemotherapy is an important area of study. CHB refers to persistent HBV infection characterized by the presence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) for more than 6 months. OBI, on the other hand, is defined as the presence of HBV DNA in the absence of detectable HBsAg[2]. Understanding the prevalence of CHB and OBI in this patient population is crucial for implementing appropriate preventive measures and antiviral prophylaxis to prevent HBV reactivation (HBVr). Previous studies have reported varying prevalence rates of CHB and OBI among cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy, highlighting the need for further investigation[3-5]. By determining the prevalence of CHB and OBI in this specific patient population, this study will contribute to the existing knowledge on HBV infection in the context of cancer chemotherapy. The findings will provide valuable insights into the need for routine screening, antiviral prophylaxis, and infection control measures to prevent HBVr and associated complications in oncology and hematology-oncology patients undergoing chemotherapy.

This observational study estimated the prevalence of CHB and OBI in newly diagnosed oncological and hematology-oncology patients before starting chemotherapy. The study population included both male and female patients from urban and rural areas, aged 18 years or older, who were seeking treatment at a tertiary care oncology center. Patients with solid organ cancer, leukemia, and lymphoma, as well as those planning to undergo chemotherapy (standard chemo

Data were collected from a total of 400 patients over 2 years. All patients underwent screening for HBsAg and total anti-HBc. Patients who tested positive for either of these markers were further tested for HBV DNA quantification using polymerase chain reaction. All patients who were identified as CHB or OBI were started on antiviral prophylaxis with entecavir or tenofovir and followed up at 6 and 12 months with HBV DNA and liver function tests. The data collected from the patients were recorded on an Excel spreadsheet for further analysis.

The collected data were analyzed using appropriate statistical methods. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population. The prevalence of CHB and OBI was estimated based on the number of patients testing positive for HBsAg, total anti-HBc, and HBV DNA. The statistical analysis determined the prevalence rates and associated confidence intervals (CIs) for CHB and OBI in the study population.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the relevant ethical committee. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before their inclusion in the study. Confidentiality and privacy of patient information were strictly maintained throughout the study.

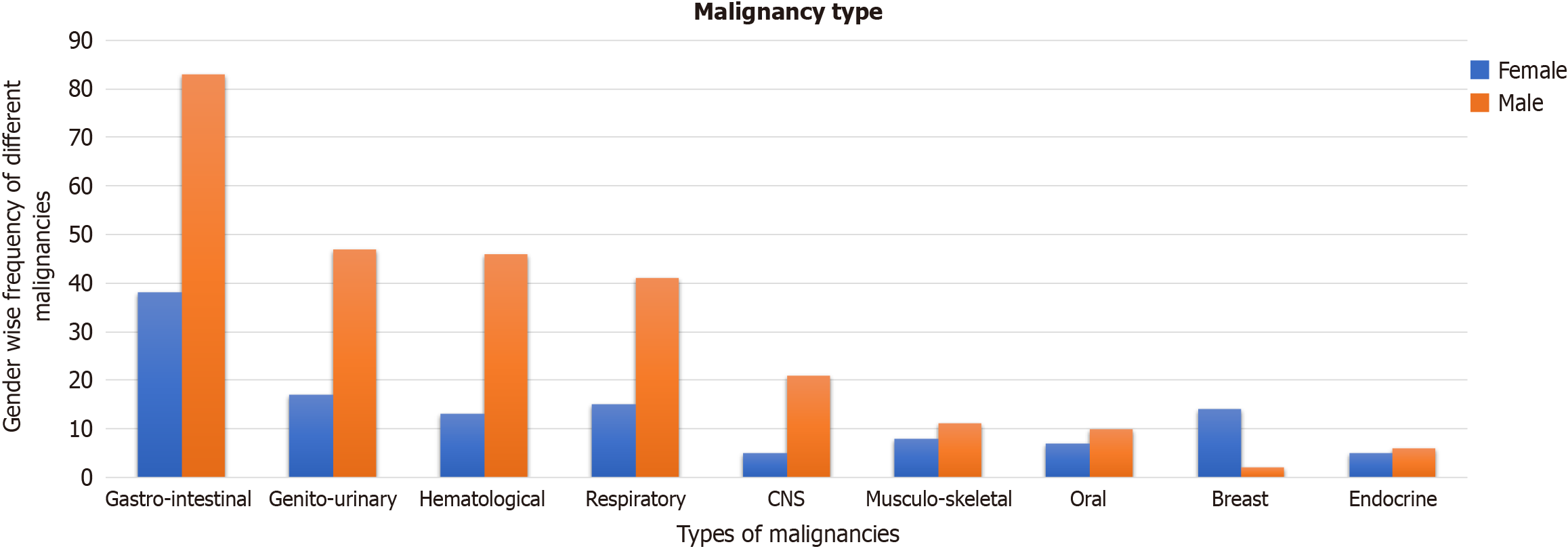

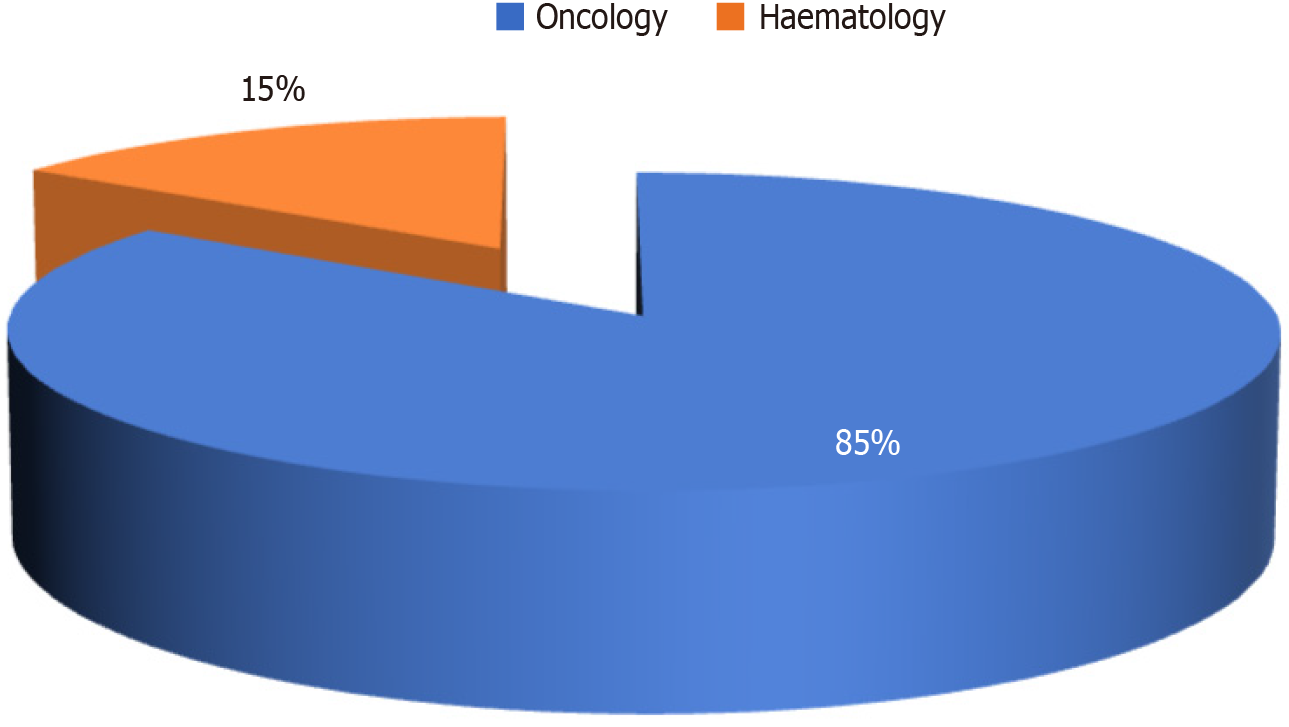

In this observational study, we investigated the prevalence of CHB and OBI in a cohort of 400 patients visiting the oncology and hematology departments with different types of malignancies (Figure 1). Among the 400 subjects studied, 129 (32.3%) were females and 271 (67.8%) were males. The mean age of the study group was 51.34 years (95%CI: 49.83-52.85). Most of the participants were oncology patients (339, 84.8%), with only (61, 15.3%) patients with hematolymphoid malignancies (Figure 2).

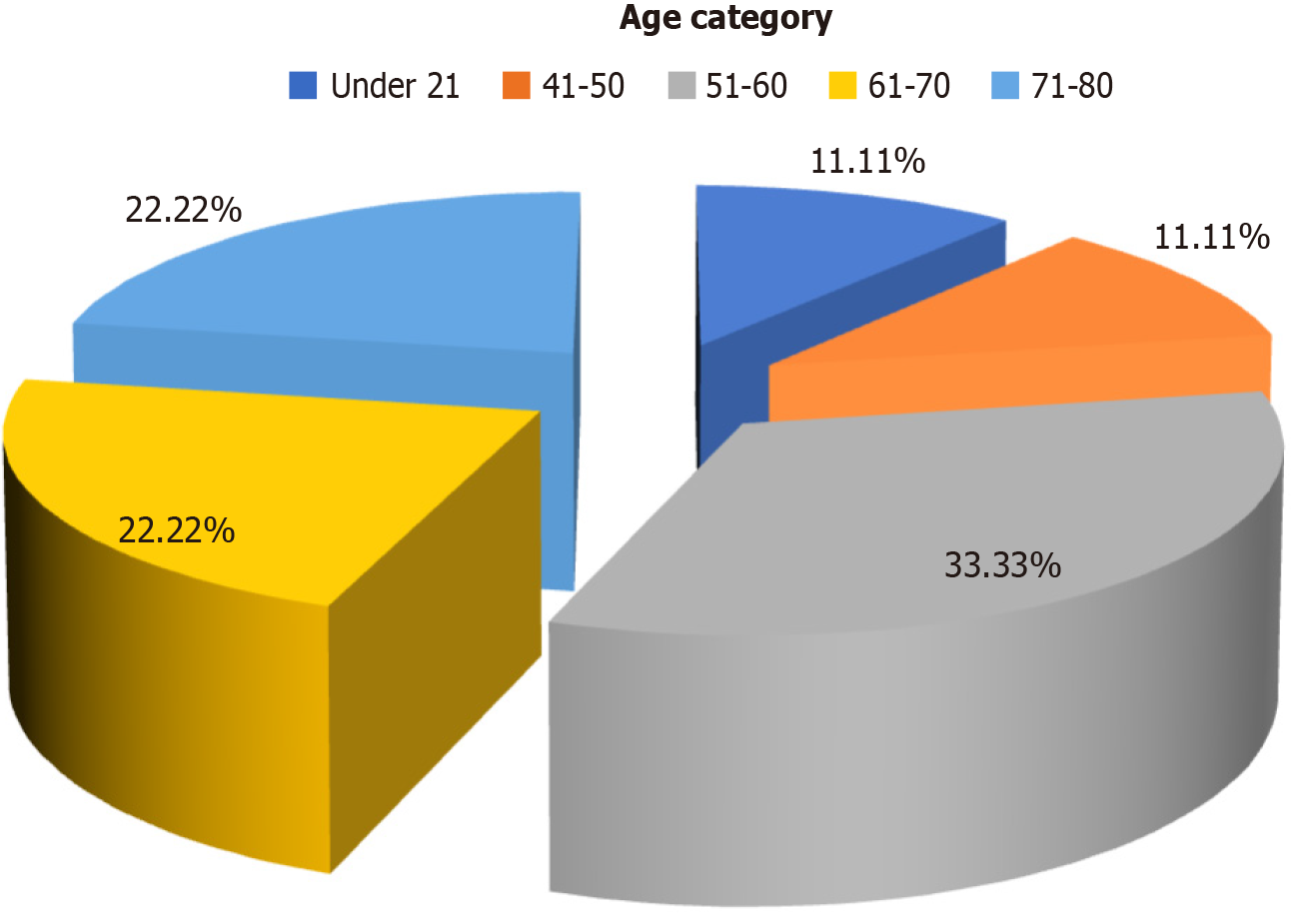

A total of 9 patients (2.3%) tested positive for HBsAg (Figure 3) of whom 7 were above the age of 50 years and 2 were below 50 years (Figure 4). The distribution of cancer types among these patients included 5 with hepatocellular carcinoma, 2 with colon cancer, 1 with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and 1 with pancreatic cancer. Five patients among them had a history of jaundice, of whom 3 were documented to have acute hepatitis B infection (Table 1). Only 2 of them had elevated liver enzymes. Two patients had high HBV DNA levels, which were undetectable at the 6- and 12-month follow-ups (Table 2). Among all HBsAg-negative cases, 3 patients tested positive for total anti-HBc. Among these patients, 1 had acute myeloid leukemia, 1 had a non-seminomatous germ cell tumor, and 1 had colon cancer (Table 3). Two of these patients had a history of jaundice in the past. None of the patients with OBI had detectable HBV DNA levels, and their liver enzymes were within the normal range (Table 4). All patients with CHB and OBI were started on antiviral prophylaxis (tenofovir or entecavir) and were followed up at 6 and 12 months. On follow-up, there was clearance of viral load and normalization of liver enzymes (Table 2).

| Patient demographics | Number of patients | Percentage | |

| Sex | Female | 1 | 11.1 |

| Male | 8 | 88.9 | |

| Malignancy | ALL | 1 | 11.1 |

| Colon | 2 | 22.2 | |

| HCC | 5 | 55.6 | |

| Pancreas | 1 | 11.1 | |

| USG | Coarse liver | 5 | 55.6 |

| Normal | 4 | 44.4 | |

| Past history of jaundice | No | 4 | 44.4 |

| Yes | 5 | 55.6 | |

| Positive family history | No | 8 | 88.9 |

| Yes | 1 | 11.1 | |

| Past history of surgeries | No | 8 | 88.9 |

| Yes | 1 | 11.1 | |

| History of transfusion in the past | No | 8 | 88.9 |

| Yes | 1 | 11.1 | |

| History of acute hepatitis B in the past | No | 6 | 66.6 |

| Yes | 3 | 33.3 | |

| Patient | 0 months | 6th months | 12th months | |||

| HBV DNA | Liver enzymes | HBV DNA | Liver enzymes | HBV DNA | Liver enzymes | |

| 1 | TND | Normal | TND | Normal | TND | Normal |

| 2 | TND | Normal | TND | Normal | TND | Normal |

| 3 | TND | Normal | TND | Normal | TND | Normal |

| 4 | TND | Normal | TND | Normal | TND | Normal |

| 5 | TND | Normal | TND | Normal | TND | Normal |

| 6 | TND | Normal | TND | Normal | TND | Normal |

| 7 | TND | Normal | TND | Normal | TND | Normal |

| 8 | HIGH | Elevated > 2X UNL | TND | Normal | TND | Normal |

| 9 | HIGH | Elevated > 2X UNL | TND | Normal | TND | Normal |

| Patient demographics | No. of patients | Percentage | |

| Age | 52 yr | 1 | 33.3 |

| 75 yr | 1 | 33.3 | |

| 78 yr | 1 | 33.3 | |

| Sex | Female | 1 | 33.3 |

| Male | 2 | 66.7 | |

| Malignancy | AML | 1 | 33.3 |

| Colon | 1 | 33.3 | |

| NSGCT | 1 | 33.3 | |

| USG | Normal | 1 | 33.3 |

| Coarse liver | 2 | 66.7 | |

| History of Jaundice | Yes | 2 | 66.7 |

| No | 1 | 33.3 | |

| History of blood transfusion in the past | Yes | 1 | 33.3 |

| No | 2 | 66.7 | |

| History of surgery in the past | Yes | 1 | 33.3 |

| No | 2 | 66.7 | |

| Family history | Yes | 0 | 0.0 |

| No | 3 | 100.0 | |

| Patient | 0 months | 6th months | 12th months | |||

| HBV DNA | Liver enzymes | HBV DNA | Liver enzymes | HBV DNA | Liver enzymes | |

| 1 | TND | Normal | TND | Normal | TND | Normal |

| 2 | TND | Normal | TND | Normal | TND | Normal |

| 3 | TND | Normal | TND | Normal | TND | Normal |

This study identified a prevalence of CHB of 2.3% (95%CI: 1.0-4.2) and OBI of 0.8% (95%CI: 0.2-2.3) within the study group. Two patients in the CHB subgroup had high HBV-DNA levels with deranged liver enzymes wherein none of these patients knew their HBV status before our study. This reiterates the importance of such screening tests before immunosuppressive therapies. Anti-viral prophylaxis was initiated in both the CHB and OBI (moderate to severe risk) patients. These patients were followed up at 6 and 12 months, but no reactivation was noted. For those who had high viral load, 6 and 12-months follow-up revealed clearance of viral load.

These results provide valuable insights into the burden of hepatitis B infection in this specific patient population and have important implications for clinical management and preventive strategies. The prevalence of CHB in the study cohort is consistent with previous studies reporting a wide range of prevalence rates among cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy[3]. Furthermore, the prevalence of OBI in the study group was estimated to be 0.8%. Although OBI is often considered a low-level infection, it can still pose a risk of transmission, especially in immunocompromised individuals[5]. Identifying OBI in this patient population underscores the importance of infection control measures to prevent HBV transmission in healthcare settings. Among the patients who tested positive for HBsAg, the majority were above the age of 50 years. This is in line with previous studies that have shown an increased risk of CHB infection with advancing age[6]. It is noteworthy that none of the patients with OBI had detectable HBV DNA levels, and their liver function tests were within the normal range. This suggests that these patients may have resolved their HBV infection or have very low-level viral replication. However, it is important to monitor these individuals closely, as OBI can still pose a risk of reactivation under immunosuppressive conditions. Loss of immune control over HBV is a crucial event in HBVr, leading to an increase in HBV DNA levels among individuals previously exposed to HBV[7]. The immune system plays a role in partially controlling viral replication in these individuals, and this control can be disrupted by exposure to immunosuppressive therapy[8]. HBVr can occur due to the ability of HBV to remain latent in the liver as covalently closed circular DNA and its capacity to alter the immune system of infected individuals[9]. Weakening of cellular immune responses during immunosuppressive therapy or chemotherapy can increase HBV replication, leading to HBVr[10]. In a study from Hong Kong, among 104 patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma undergoing treatment 46 were found to be HBsAg-negative and anti-HBc-positive. Twenty-one of these patients were treated with R-CHOP and twenty-five were treated with CHOP alone. Of patients treated with R-CHOP, 5 (25%) developed HBVr. None of the patients treated with CHOP therapy developed HBVr[11].

In another study, 115 patients with non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma (NHL) who were receiving at least one dose of rituximab were examined for the risk of HBVr. Fifteen of these patients were HBsAg-positive, and ten of them did not receive antiviral prophylaxis during treatment. In all, 80% of patients who were HBsAg-positive and received rituximab therapy without antiviral prophylaxis experienced HBV-related hepatitis. Of the 95 patients with NHL who were HBsAg-negative, 4 developed HBV-related hepatitis of whom 2 died due to fulminant hepatic failure[12].

The findings of this study have important clinical implications. Routine screening for hepatitis B infection should be considered in oncology and hematology patients before initiating chemotherapy or immunosuppressive therapies. Identifying individuals with CHB and OBI allows for appropriate management strategies, including antiviral prophy

The issue of reactivation of hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is often missed due to inadequate evaluation, especially for occult HBV infection (OBI). This reactivation following immunosuppression can lead to liver dysfunction, which in turn either impacts the continuation of therapy and/or increases the morbidity and mortality in an already immunocompromised patient. We attempted to study the same to know the current status of evaluation protocols and the prevalence of HBV infection as well as reactivation.

The protocols for the evaluation of patients with malignancy need to include checking for OBI as it carries risk of reactivation following chemotherapy during treatment. The presence of pre-existing HBV infection always involves a gastroenterology or hepatology consult regarding the consideration of antiviral therapy. On the other hand, OBI is not considered routinely in pretreatment evaluation and therefore any possible prophylaxis is delayed. More data are required in these specific situations to formulate better protocols for the future.

Our primary objective was to determine the prevalence of chronic HBV (CHB) and OBI among oncology and hema

In this observational study, the prevalence of CHB and OBI was assessed among patients receiving chemotherapy. Serological markers of HBV infection [hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)/anti-hepatitis B core antigen (HBc)/anti-hepatitis B surface antibody] were evaluated for all participants. Those who tested negative for HBsAg but positive for total anti-HBc were tested for HBV DNA levels. Due ethical clearance was taken and data of 400 patients were collected over 2 years. Appropriate statistics were applied for analysis in this observational study.

In our study, the prevalence of CHB within the study cohort was determined to be 2.3% [95% confidence interval (95%CI): 1.0-4.2]. Additionally, the prevalence of OBI among the study participants was found to be 0.8% (95%CI: 0.2-2.3). Although the prevalence seems low, on consideration of the people affected by malignancy worldwide, the numbers may be significant.

The findings of this study highlight the importance of screening for hepatitis B infection in oncology and hematology-oncology patients undergoing chemotherapy. Identifying individuals with CHB and OBI is crucial for implementing appropriate antiviral prophylaxis to prevent the reactivation of HBV infection, which can lead to increased morbidity and mortality.

The direction of future research should be to actively look for OBI.

| 1. | Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B: update 2009. Hepatology. 2009;50:661-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2125] [Cited by in RCA: 2176] [Article Influence: 128.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 2. | Franz C, Perez Rde M, Zalis MG, Zalona AC, Rocha PT, Gonçalves RT, Nabuco LC, Villela-Nogueira CA. Prevalence of occult hepatitis B virus infection in kidney transplant recipients. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2013;108:657-660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yeo W, Chan PK, Zhong S, Ho WM, Steinberg JL, Tam JS, Hui P, Leung NW, Zee B, Johnson PJ. Frequency of hepatitis B virus reactivation in cancer patients undergoing cytotoxic chemotherapy: a prospective study of 626 patients with identification of risk factors. J Med Virol. 2000;62:299-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer. 2015;136:E359-E386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20108] [Cited by in RCA: 20725] [Article Influence: 1884.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (23)] |

| 5. | Hwang JP, Lok AS. Management of patients with hepatitis B who require immunosuppressive therapy. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11:209-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 167] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kao JH, Chen DS. Global control of hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2:395-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 596] [Cited by in RCA: 615] [Article Influence: 25.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cornberg M, Wong VW, Locarnini S, Brunetto M, Janssen HLA, Chan HL. The role of quantitative hepatitis B surface antigen revisited. J Hepatol. 2017;66:398-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 271] [Article Influence: 30.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Perrillo RP, Gish R, Falck-Ytter YT. American Gastroenterological Association Institute technical review on prevention and treatment of hepatitis B virus reactivation during immunosuppressive drug therapy. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:221-244.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 352] [Cited by in RCA: 400] [Article Influence: 36.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 9. | Gentile G, Antonelli G. HBV Reactivation in Patients Undergoing Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: A Narrative Review. Viruses. 2019;11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Tavakolpour S, Alavian SM, Sali S. Hepatitis B Reactivation During Immunosuppressive Therapy or Cancer Chemotherapy, Management, and Prevention: A Comprehensive Review-Screened. Hepat Mon. 2016;16:e35810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yeo W, Chan TC, Leung NW, Lam WY, Mo FK, Chu MT, Chan HL, Hui EP, Lei KI, Mok TS, Chan PK. Hepatitis B virus reactivation in lymphoma patients with prior resolved hepatitis B undergoing anticancer therapy with or without rituximab. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:605-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 519] [Cited by in RCA: 507] [Article Influence: 29.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Smalls DJ, Kiger RE, Norris LB, Bennett CL, Love BL. Hepatitis B Virus Reactivation: Risk Factors and Current Management Strategies. Pharmacotherapy. 2019;39:1190-1203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: American Gastroenterological Association, 1050754; American College of Gastroenterology, 51519; American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, 151100.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: India

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Shahid M, Pakistan S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Zheng XM