Published online Mar 18, 2026. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v16.i1.114592

Revised: October 24, 2025

Accepted: December 31, 2025

Published online: March 18, 2026

Processing time: 113 Days and 2 Hours

Stem cells are pluripotent cells that can divide and differentiate, forming many different types of cells. Stem cells can be obtained from various sources, with em

Core Tip: Treatment of some diseases in the pediatric population can be ineffective with standard therapy. The use of stem cells to treat various diseases in this population has increased over the last few years due to technological and genetic advancements that have allowed more targeted therapies to be used. Ethical and legal issues remain a significant hindrance in research and clinical studies related to stem cells.

- Citation: Mwita RP, Özdemir Ö. Stem cell transplantation in immuno-hematologic and infectious diseases. World J Transplant 2026; 16(1): 114592

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3230/full/v16/i1/114592.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v16.i1.114592

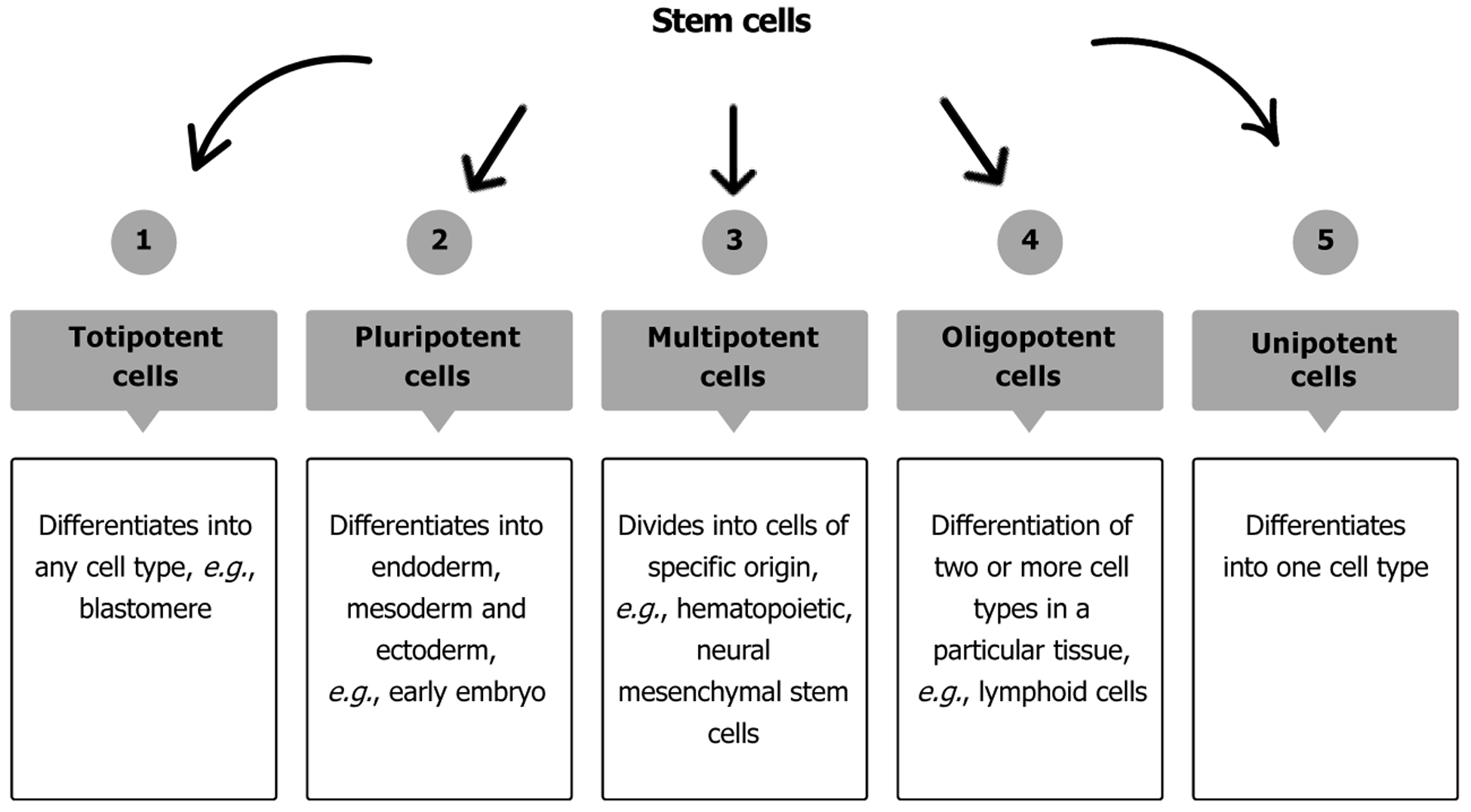

Stem cells are pluripotent cells that can regenerate and differentiate into various types of cells. Stem cells can be obtained from bone marrow, fat, dental pulp, blood, amniotic fluid, umbilical cord, and other tissues (Figure 1)[1-5]. Embryonic stem cells are derived from embryos at a specific period, nearly 4 or 5 days after fertilization[6]. Though not as effective in differentiation, adult stem cells can also be used[7,8]. Pluripotent cells can differentiate into many cells, while oligopotent cells can differentiate into a limited number. Oligopotent cells include myeloid cells, which can differentiate into any blood cells found in the body, such as hematopoietic stem cells, lymphoid progenitor cells, and mammary stem cells. Table 1 shows the difference between pluripotent and oligopotent stem cells and the types of pediatric diseases that can be treated[5,8]. The use of stem cells to treat different diseases, especially where the standard treatment is ineffective, has increased over the years.

| Pluripotent stem cells | Oligopotent stem cells |

| They can differentiate into any type of cell in the body | They can self-renew and differentiate into hematopoietic stem cells |

| The functions of the original cells are difficult to achieve | Non-controversial, accepted distinctly by patients |

| Immunogenicity i.e., immunological mismatch of the stem cells to the body is a major problem | Mainly found in bone marrow |

| Can be differentiated into endoderm, ectoderm, mesoderm, allowing a wide range of use in treatment. High rates of genetic instability increase tumorigenicity | Differentiate into red and white blood cells and platelets. Can also result in hematopoietic malignancy |

| Used to treat heart diseases e.g., long QT syndrome, Brugada syndrome, cardiomyopathies etc. muscle disorders, diabetes, kidney diseases, cystic fibrosis, spinal cord injury and many more | Used to treat: Malignancies e.g., leukemia, lymphoma, neuroblastoma, Ewing sarcoma, choriocarcinoma and phagocyte disorders. Congenital diseases e.g., lysosomal storage disorders, mucopolysaccharidoses, glycoproteinoses, ataxia telangiectasia, Di George syndrome, severe combined immunodeficiency, aplastic anemia etc. |

Usually, it is not used as the first-line treatment due to the availability of less invasive therapies, but also due to the complicated procedures used and the side effects of the transplantation process. Many studies have shown that many diseases could be treated by using stem cell therapy[9]. Still, ethical and legal issues, expenses, and many other factors hinder more studies. The new 2021 International Society for Stem Cell Research guideline, compared to the previous one, provided a more favorable environment to conduct advanced studies in this field by adding new recommendations that address recent advancements involving embryos, organoids, gene editing, chimeras, and stem cell-based embryo models[10].

In this article, we will review the applications of stem cells and their limitations, which are derived from these technologies, mainly focusing on immunohematologic and infectious diseases. The review consists of various sections, like acquisition of stem cells, where we explain in an orderly manner how stem cells are obtained, prepared, and purified before use. The next section addresses the use of stem cells in diseases such as Bruton’s agammaglobulinemia, Type 1 diabetes mellitus, aplastic anemia, colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii sepsis, Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection, and leukemia. In the discussion section, we discuss the stem cell developments over the years, the stem cell market, the prices, and the complications that occur because of stem cell use. The future expectations section explains the newly developed gene editing methods and discoveries that might cause significant improvements in this field.

The relevant literature was searched in PubMed and Google Scholar using the keywords “stem cells”, “immunology”, “hematology”, “infectious disease”, “Bruton”, “leukemia”, “diabetes”, “aplastic anemia”, and “sepsis” for the last 25 years (published from January 2000 to July 2025). Articles with titles that do not include these keywords are not screened.

Stem cells are acquired through a series of processes. Cells are cultured in isolated conditions to avoid complications resulting from cell overproduction[11]. In vitro stem cells can cause chromosomal abnormalities and mutations[8]. Stem cells undergo asymmetric division, producing slightly larger cells[12]. Stem cells are produced based on the number of cells required for a particular treatment. For example, pancreatic islet transplantation requires about 1 billion cells[13]. Other requirements include bioreactor dimensions for generating multiple cells, medium, and the duration necessary for the production. A culture medium is needed to produce specific cell types. Ongoing studies exist using xeno-free media to culture stem cells[14]. A matrix is required for the produced cells to attach. Bioreactors are necessary to provide a regulated and controlled environment for cell growth. Hematopoietic stem cells have shown the most successful results in producing various progenitor cells[15]. Sources of stem cells include bone marrow, peripheral blood, umbilical cord, etc.[16,17]. The stem cells are expanded and scaled up in vitro. The number of bone marrow cells has increased in the presence of CD34+ cells. The function of CD34+ is not entirely known yet, but experimental studies suggest that CD34+ regulates the proliferation and maintenance of stem cells[18,19]. Transcription markers are added depending on the cells produced[20,21].

The differentiated cells are enriched for safety and purity. The purification process involves both positive and negative selection. For example, in cardiomyocytes, the specific surface marker CD166/activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule is used to isolate cardiomyocytes from embryonic cultures to produce stem cells, which can be used in cardiac cell damage, like infarction, an irreversible damage to myocytes. These specific cells have also shown a decrease in post-transplant complications like transplant rejection. Cytotoxic monoclonal antibodies eliminate[22,23] undifferentiated cells to reduce complications like teratoma formation[24,25]. All types of stem cells have pros and cons as shown in the table below (Table 2). The stem cells obtained can be implanted after the donor and recipient’s matching human leukocyte antigen (HLA) is confirmed.

| Stem cells | Pros | Cons |

| Fetal cells | Safe and effective for transplantation | Tissue availability. Ethical issues |

| Embryonic stem cells | Pluripotent, have stable karyotype and can differentiate into a wide variety of cells. Autologous transplant so less risk of GVHD | Over proliferation can cause tumor formation. Ethical concerns. High rate of rejection. Limited supply and availability |

| Pluripotent stem cells | Reduces ethical issues. Lower rejection risk since used as specific therapy | High risk of tumor formation i.e., teratoma. High risk due to reprogramming. Hard to make standard therapy |

| Reprogrammed stem cells | Low tumor formation risk. Lower rejection risk. Reduced ethical issues. Undergoes simple formation process | Low efficiency. Not deeply understood due to lack of enough studies. Hard to standardize |

| Adult stem cells | No ethical issues | Restricted potentials |

Also known as X-linked agammaglobulinemia, Bruton agammaglobulinemia is an immunodeficiency disease commonly affecting pediatric patients aged 1-5[26]. It is caused by a genetic mutation of the Bruton tyrosine kinase gene[27]. It presents with low immunoglobulin levels due to a significantly reduced or complete lack of B cells in circulation[28,29]. Standard therapy includes gamma globulin therapy and antibiotics[30,31].

The patients undergo hydration therapy before transfusion, then are pretreated with hydrocortisone and anti

Pancreatic beta cells produce insulin, an essential regulator of energy metabolism throughout the body, by using carbohydrates, fats, and proteins[38,39]. The amount of insulin in the body varies depending on the energy required and the metabolites available. Type 1 diabetes mellitus is a disease that results from a lack of islet beta cells of the pancreas. In type 1 diabetes, insulin production is lacking because an autoimmune process selectively destroys β cells[40,41]. The lack of insulin causes an increase in blood glucose level, resulting in various metabolic complications due to non-functioning enzymatic reactions and deposition in different organs over the years. Keeping blood glucose levels as close to normal as possible is essential to avoid long-term complications such as cardiovascular, nephrogenic, and ophthalmologic diseases[42,43]. The standard treatment of type 1 diabetes is insulin replacement therapy.

The advancements in stem cell technologies have led to human clinical trials using stem cell-derived pancreatic products. In one study, stem cell-derived pancreatic endoderm cell population known as pancreatic endoderm cells was produced in vivo[44,45]. The Encaptra® device was designed to immunoprotect the cells using a cell-impermeable membrane[46]. The engraftment was tolerated but halted due to insufficient engraftment materials. Another study demonstrated glucose-responsive C-peptide production 6-9 months post-transplant as the grafted cells matured from pancreatic progenitors into endocrine cells[47,48]. The current differentiation methodologies have challenges, including producing different cell types resembling enterochromaffin cells, which are endocrine[49]. Also, the graft cells do not work exactly as the original cells, requiring a lot of cells to be engrafted. Currently, ongoing studies are developing more advanced islets through a multistep differentiation process that attempts to mimic stages of embryonic development[50]. A triple-blinded, randomized study using mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in 21 patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus showed impressive results, including reduction of hypoglycemic episodes, improved glycated hemoglobin levels, and improved quality of life[51].

Aplastic anemia is when the bone marrow fails to produce hematopoietic cells, resulting in various complications. It is a rare condition with different etiologies, including benzene, specific animal fertilizers, and pesticide exposure[52]. Infectious agents may cause aplastic anemia, though not commonly, because it usually presents as an immune-mediated disease. HLA-DR2 is over-represented among patients with aplastic anemia, and its presence predicts a better response to cyclosporine[53,54]. Despite an unknown mechanism of action, horse anti-thymocyte globulin is the only drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of aplastic anemia[55].

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation can offer a cure, especially in the pediatric population. Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation from a histocompatible matched sibling is most curative. Studies have shown a 5-year survival rate of approximately 77%[56]. The most important indications of stem cell transplantation include age and HLA matching to avoid graft-vs-host disease (GVHD)[57]. Evaluation of previous bacterial, viral, and fungal infections should be conducted and eradicated before the transplantation. Prophylaxis for GVHD includes a short course of methotrexate; some protocols add alemtuzumab[58]. Post-transplant cyclosporine levels should be maintained around 200-300 ng/mL, and tacrolimus levels between 10 and 15 ng/mL. This treatment should be continued for 9-12 months, followed by a taper over 3 months[36]. The graft failure rate has been reported to range from 0% to 26%[59]. Chimerism analysis is performed in 1-month, 3-month, 6-month, and 12-month post-transplant intervals. Survival rate has improved rapidly from 48% to 90% over the last 40 years[60,61], making stem cell transplant the most effective treatment for aplastic anemia. A retrospective study reviewed 127 patients with severe aplastic anemia treated with hematopoietic stem cells. The study showed decreased graft rejection and an overall 5-year survival of approximately 91%[62].

Sepsis is one of the leading causes of death globally. According to studies, the estimated number of cases ranges from 19.9 million to 48.9 million[63,64]. Colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii, a microorganism with multidrug resistance of approximately 33%[65], is very hard to treat with standard treatment. It has a mortality rate as high as 70%[66]. The standard therapy includes a colistin-fosfomycin combination with no significant side effects[67,68].

Currently, there are studies on using MSCs to treat this drug-resistant sepsis[69]. MSCs have antibacterial and anti-inflammatory properties, and they increase the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines [interleukin (IL)-10, IL-13] while decreasing the production of proinflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor-α, IL-1, IL-6). Although animal models have shown a successful response to MSC, it is not practical to explore findings on sepsis patients by relating them to animal studies[70]. The preliminary data for the Russian clinical trial of MSCs for septic shock (NCT01849237) have been reported[71]. Despite fewer published studies, treating colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii sepsis using MSCs and the colistin-fosfomycin regimen holds significant potential for reducing bacterial load and preventing disease progression. In an experimental model study design of mice, Acinetobacter baumannii was injected into the subjects after administering different treatment modalities, and then the bacterial clearance was observed. The clearance of bacterial load was highest in groups in which MSCs were administered. The study concluded that adding stem cells is essential for clearing bacterial load and preventing histopathologic damage[72].

Infection is the primary cause of death in the pediatric population[73], partly because the immune system is not fully developed enough to fight the pathogens. Pseudomonas aeruginosa is one of the most difficult microorganisms to treat due to the development of resistance strains even to newly developed treatments. Antibiotic exposure in neonates increases the incidence of superinfection, necrotizing enterocolitis, and death[74].

Studies have shown that using human umbilical cord MSCs extensively treats infectious diseases in neonates. These cells can proliferate and differentiate into various cells[75]. A study showed that human umbilical cord MSCs could be effective against Pseudomonas aeruginosa resistant strains[76]. The study assessed the effects of stem cells on Pseudomonas-resistant bacteria. Stem cells were infected with the bacteria for 6 hours. Then, the ability of stem cells to inhibit bacterial growth was evaluated by incubation. The results showed that the development of Pseudomonas was remarkably inhibited compared to the control medium, proving the effectiveness of the therapy. Stem cells proved to have a more potent antibacterial effect. An animal study was conducted to check the antimicrobial properties of MSCs against various bacteria affecting patients with cystic fibrosis. The study found that the number of Pseudomonas bacteria was decreased in groups where stem cells were administered and further showed additive effects with combination therapy with geneticin[77].

Leukemia is a condition that occurs due to abnormal proliferation and differentiation of hematopoietic cells. It is the most common malignancy of childhood. Leukemia can be divided into myeloid and lymphoblastic leukemia, subdivided into acute and chronic[78,79]. Leukemia is managed with multi-agent systemic chemotherapy for over 2 years to 3 years. A more targeted therapy has been developed for patients with a positive Philadelphia chromosome[80]. Targeted therapy has much lower side effects than non-targeted therapy, but cannot be used in all types of leukemia.

The production of hematopoietic cells from pluripotent stem cells requires a change from endothelial to hematopoietic progenitor cells[81]. Hematopoietic stem cells can be obtained from various types of cells, including human embryonic stem cells, induced pluripotent stem cells, tiny embryonic-like stem cells, and many others. Transcription factors res

In 1998, the first human embryonic stem cell line was derived, creating a significant revolution in the stem cell field. Over the years, research has been conducted, and in 2012, a Nobel Prize was awarded for the discovery of mature cell reprogramming to produce pluripotent cells. This allowed more studies to be undertaken due to the increased sources from which stem cells could be obtained. In 2014, the first clinical trial with human induced pluripotent stem cells was initiated[84]. The primary gene editing methods include clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats, organoids, and chimeric embryos. Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/CRISPR-associated protein 9 is a popular gene editing method involving adding, removing, or changing DNA sections. The preparation process involves the following steps: The CRISPR-associated protein 9 scans for a specific DNA protospacer adjacent motif, the adjacent DNA segment is unwound, and if it matches the sequence in crRNA, then CRISPR-associated protein 9 cuts both strands of the DNA, creating a double-stranded DNA break. The obtained products can then be introduced into the nu

Trials have shown outstanding results in hematologic diseases like sickle cell anemia[86,87]. Factors like genetic mismatching and the pre-transplantation treatments impede the use of stem cells. Stem cell therapy is a costly treatment method. Analysis of the global market showed that in 2022, the total budget was approximately US $287 million and is predicted to rise to US $1172 million within 8 years. For each treatment, the cost ranges from 10000$ to 60000$[88]. This prevents many patients from accessing therapy.

Stem cell transplantation leads to severe immune deficiency, thus a high risk of infection. The innate immune system recovers earlier, while the adaptive immune system, especially T-cells, remains impaired for years. Complications of stem cell therapy can be divided into two groups: Early and late complications. Early complications include infections, acute GVHD, transplant failure, pneumonitis, veno-occlusive disease, cardiac failure, hemorrhagic cystitis due to the use of highly cytotoxic agents for pretreatment, etc. Late complications include chronic GVHD, autoimmune disorders, secondary malignancy, infections, etc. Stem cell treatment has shown an increased success in treating different diseases, including drug-resistant infections. Since many studies are not conducted in clinical settings, understanding their effects on human beings is limited. Many clinical studies are limited by one or another factor, making it hard to utilize the therapy effectively[89,90]. Since the process is a multi-procedure and requires an extended follow-up, some studies showed several patients withdrawing from the study[91]. The limitations of performing studies in the pediatric population lead to insufficient information concerning this group. The previous guidelines on stem cell research restricted most studies from being conducted due to ethical and legal issues. The 2021 International Society for Stem Cell Research guideline consists of 3 categories of research: Category one research, exempted from review; category two research, reviewed but with specialized oversight; and category 3, into which research is not allowed. Despite being revised, there are still restrictions, especially on the use of embryonic stem cells, that prevent more trials from being performed[92]. For example, many studies directed to the nervous system are considered high risk, thus not performed clinically despite showing promising results in treating diseases like Parkinson’s disease, stroke, and spinal cord diseases[93]. This gives organoid studies an upper hand, creating the potential to study human development, regenerative medicines, and different diseases in detail[94].

To ensure even more successful future results, scientists are currently studying issues related to donor cells, cell pro

Regarding ethical issues, embryonic stem cells have been established from a more ethical source, i.e., surplus in vitro fertilization embryos[95]. Technological development has allowed studies like molecular regulation of myogenesis to be conducted, creating a new era of treatment of cardiac diseases[96]. Examples of studies conducted were explicitly aimed at myogenesis[97-99]. Genetic modification has also been shown to reduce the side effects and complications of the treatment since it’s more specific.

The application of stem cell therapy has been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality in groups of patients with favorable criteria for transplantation, i.e., age, comorbidities, type of stem cells used, etc. Using stem cells to treat diseases in the pediatric population is an emerging technology that still requires further research. The stem cell research guideline should be revised to create a more flexible environment for conducting research. Conditions enabling researchers to conduct studies across various fields and support from the healthcare system should be established. The long-term side effects should be studied comprehensively to establish more thorough pre- and post-transplant management procedures. The high prices prevent many patients from using the therapy. In addition, results obtained from various studies should be shared even if the survey was incomplete. Multiple solutions and study models can be constructed by understanding the weaknesses and strengths of studies. Also, by providing education about the use of embryonic stem cells and solving the ethical issues, stem cell treatment may become one of the best ways to treat drug-resistant and other conditions in pediatric patients.

| 1. | Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663-676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17989] [Cited by in RCA: 18593] [Article Influence: 929.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Takahashi K, Tanabe K, Ohnuki M, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Tomoda K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors. Cell. 2007;131:861-872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14327] [Cited by in RCA: 14570] [Article Influence: 809.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Barkeer S, Chugh S, Batra SK, Ponnusamy MP. Glycosylation of Cancer Stem Cells: Function in Stemness, Tumorigenesis, and Metastasis. Neoplasia. 2018;20:813-825. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chin MH, Mason MJ, Xie W, Volinia S, Singer M, Peterson C, Ambartsumyan G, Aimiuwu O, Richter L, Zhang J, Khvorostov I, Ott V, Grunstein M, Lavon N, Benvenisty N, Croce CM, Clark AT, Baxter T, Pyle AD, Teitell MA, Pelegrini M, Plath K, Lowry WE. Induced pluripotent stem cells and embryonic stem cells are distinguished by gene expression signatures. Cell Stem Cell. 2009;5:111-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 795] [Cited by in RCA: 736] [Article Influence: 43.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ratajczak MZ, Zuba-Surma E, Kucia M, Poniewierska A, Suszynska M, Ratajczak J. Pluripotent and multipotent stem cells in adult tissues. Adv Med Sci. 2012;57:1-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | An JH, Park H, Song JA, Ki KH, Yang JY, Choi HJ, Cho SW, Kim SW, Kim SY, Yoo JJ, Baek WY, Kim JE, Choi SJ, Oh W, Shin CS. Transplantation of human umbilical cord blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells or their conditioned medium prevents bone loss in ovariectomized nude mice. Tissue Eng Part A. 2013;19:685-696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Dulak J, Szade K, Szade A, Nowak W, Józkowicz A. Adult stem cells: hopes and hypes of regenerative medicine. Acta Biochim Pol. 2015;62:329-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Prentice DA. Adult Stem Cells. Circ Res. 2019;124:837-839. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mousaei Ghasroldasht M, Seok J, Park HS, Liakath Ali FB, Al-Hendy A. Stem Cell Therapy: From Idea to Clinical Practice. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:2850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 25.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hyun I, Clayton EW, Cong Y, Fujita M, Goldman SA, Hill LR, Monserrat N, Nakauchi H, Pedersen RA, Rooke HM, Takahashi J, Knoblich JA. ISSCR guidelines for the transfer of human pluripotent stem cells and their direct derivatives into animal hosts. Stem Cell Reports. 2021;16:1409-1415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Talleur AC, Flerlage JE, Shook DR, Chilsen AM, Hudson MM, Cheng C, Huang S, Triplett BM. Autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation for the treatment of relapsed/refractory pediatric, adolescent, and young adult Hodgkin lymphoma: a single institutional experience. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2020;55:1357-1366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bhartiya D. The need to revisit the definition of mesenchymal and adult stem cells based on their functional attributes. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2018;9:78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Emamaullee JA, Shapiro AM. Factors influencing the loss of beta-cell mass in islet transplantation. Cell Transplant. 2007;16:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Schugar RC, Robbins PD, Deasy BM. Small molecules in stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Gene Ther. 2008;15:126-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Orkin SH, Zon LI. Hematopoiesis: an evolving paradigm for stem cell biology. Cell. 2008;132:631-644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2046] [Cited by in RCA: 1894] [Article Influence: 105.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | THOMAS ED, LOCHTE HL Jr, LU WC, FERREBEE JW. Intravenous infusion of bone marrow in patients receiving radiation and chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 1957;257:491-496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 717] [Cited by in RCA: 636] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sheridan WP, Begley CG, Juttner CA, Szer J, To LB, Maher D, McGrath KM, Morstyn G, Fox RM. Effect of peripheral-blood progenitor cells mobilised by filgrastim (G-CSF) on platelet recovery after high-dose chemotherapy. Lancet. 1992;339:640-644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 610] [Cited by in RCA: 557] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Marvasti TB, Alibhai FJ, Weisel RD, Li RK. CD34(+) Stem Cells: Promising Roles in Cardiac Repair and Regeneration. Can J Cardiol. 2019;35:1311-1321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Krause DS, Fackler MJ, Civin CI, May WS. CD34: structure, biology, and clinical utility. Blood. 1996;87:1-13. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Enver T, Soneji S, Joshi C, Brown J, Iborra F, Orntoft T, Thykjaer T, Maltby E, Smith K, Abu Dawud R, Jones M, Matin M, Gokhale P, Draper J, Andrews PW. Cellular differentiation hierarchies in normal and culture-adapted human embryonic stem cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:3129-3140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 243] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Sperger JM, Chen X, Draper JS, Antosiewicz JE, Chon CH, Jones SB, Brooks JD, Andrews PW, Brown PO, Thomson JA. Gene expression patterns in human embryonic stem cells and human pluripotent germ cell tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:13350-13355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 506] [Cited by in RCA: 503] [Article Influence: 21.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hirata H, Murakami Y, Miyamoto Y, Tosaka M, Inoue K, Nagahashi A, Jakt LM, Asahara T, Iwata H, Sawa Y, Kawamata S. ALCAM (CD166) is a surface marker for early murine cardiomyocytes. Cells Tissues Organs. 2006;184:172-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rust W, Balakrishnan T, Zweigerdt R. Cardiomyocyte enrichment from human embryonic stem cell cultures by selection of ALCAM surface expression. Regen Med. 2009;4:225-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Laflamme MA, Chen KY, Naumova AV, Muskheli V, Fugate JA, Dupras SK, Reinecke H, Xu C, Hassanipour M, Police S, O'Sullivan C, Collins L, Chen Y, Minami E, Gill EA, Ueno S, Yuan C, Gold J, Murry CE. Cardiomyocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells in pro-survival factors enhance function of infarcted rat hearts. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:1015-1024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1672] [Cited by in RCA: 1619] [Article Influence: 85.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Xu C, Police S, Rao N, Carpenter MK. Characterization and enrichment of cardiomyocytes derived from human embryonic stem cells. Circ Res. 2002;91:501-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 696] [Cited by in RCA: 613] [Article Influence: 25.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Conley ME, Howard V. Clinical findings leading to the diagnosis of X-linked agammaglobulinemia. J Pediatr. 2002;141:566-571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Vetrie D, Vorechovský I, Sideras P, Holland J, Davies A, Flinter F, Hammarström L, Kinnon C, Levinsky R, Bobrow M. The gene involved in X-linked agammaglobulinaemia is a member of the src family of protein-tyrosine kinases. Nature. 1993;361:226-233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1093] [Cited by in RCA: 1085] [Article Influence: 32.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Conley ME. B cells in patients with X-linked agammaglobulinemia. J Immunol. 1985;134:3070-3074. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Nomura K, Kanegane H, Karasuyama H, Tsukada S, Agematsu K, Murakami G, Sakazume S, Sako M, Tanaka R, Kuniya Y, Komeno T, Ishihara S, Hayashi K, Kishimoto T, Miyawaki T. Genetic defect in human X-linked agammaglobulinemia impedes a maturational evolution of pro-B cells into a later stage of pre-B cells in the B-cell differentiation pathway. Blood. 2000;96:610-617. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Quartier P, Debré M, De Blic J, de Sauverzac R, Sayegh N, Jabado N, Haddad E, Blanche S, Casanova JL, Smith CI, Le Deist F, de Saint Basile G, Fischer A. Early and prolonged intravenous immunoglobulin replacement therapy in childhood agammaglobulinemia: a retrospective survey of 31 patients. J Pediatr. 1999;134:589-596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Plebani A, Soresina A, Rondelli R, Amato GM, Azzari C, Cardinale F, Cazzola G, Consolini R, De Mattia D, Dell'Erba G, Duse M, Fiorini M, Martino S, Martire B, Masi M, Monafo V, Moschese V, Notarangelo LD, Orlandi P, Panei P, Pession A, Pietrogrande MC, Pignata C, Quinti I, Ragno V, Rossi P, Sciotto A, Stabile A; Italian Pediatric Group for XLA-AIEOP. Clinical, immunological, and molecular analysis in a large cohort of patients with X-linked agammaglobulinemia: an Italian multicenter study. Clin Immunol. 2002;104:221-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Shillitoe BMJ, Ponsford M, Slatter MA, Evans J, Struik S, Cosgrove M, Doull I, Jolles S, Gennery AR. Haematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant for Norovirus-Induced Intestinal Failure in X-linked Agammaglobulinemia. J Clin Immunol. 2021;41:1574-1581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Nuñez C, Nishimoto N, Gartland GL, Billips LG, Burrows PD, Kubagawa H, Cooper MD. B cells are generated throughout life in humans. J Immunol. 1996;156:866-872. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Hentschke P, Remberger M, Mattsson J, Barkholt L, Aschan J, Ljungman P, Ringdén O. Clinical tolerance after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: a study of influencing factors. Transplantation. 2002;73:930-936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Woolfrey AE, Anasetti C, Storer B, Doney K, Milner LA, Sievers EL, Carpenter P, Martin P, Petersdorf E, Appelbaum FR, Hansen JA, Sanders JE. Factors associated with outcome after unrelated marrow transplantation for treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in children. Blood. 2002;99:2002-2008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Howard V, Myers LA, Williams DA, Wheeler G, Turner EV, Cunningham JM, Conley ME. Stem cell transplants for patients with X-linked agammaglobulinemia. Clin Immunol. 2003;107:98-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Abu-Arja RF, Chernin LR, Abusin G, Auletta J, Cabral L, Egler R, Ochs HD, Torgerson TR, Lopez-Guisa J, Hostoffer RW, Tcheurekdjian H, Cooke KR. Successful hematopoietic cell transplantation in a patient with X-linked agammaglobulinemia and acute myeloid leukemia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:1674-1676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Haeusler RA, McGraw TE, Accili D. Biochemical and cellular properties of insulin receptor signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018;19:31-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 482] [Cited by in RCA: 522] [Article Influence: 65.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Saltiel AR, Kahn CR. Insulin signalling and the regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. Nature. 2001;414:799-806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3583] [Cited by in RCA: 3709] [Article Influence: 148.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (11)] |

| 40. | Powers AC. Type 1 diabetes mellitus: much progress, many opportunities. J Clin Invest. 2021;131:e142242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | DiMeglio LA, Evans-Molina C, Oram RA. Type 1 diabetes. Lancet. 2018;391:2449-2462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 595] [Cited by in RCA: 1056] [Article Influence: 132.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group; Nathan DM, Genuth S, Lachin J, Cleary P, Crofford O, Davis M, Rand L, Siebert C. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:977-986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17510] [Cited by in RCA: 16442] [Article Influence: 498.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 43. | Nathan DM; DCCT/EDIC Research Group. The diabetes control and complications trial/epidemiology of diabetes interventions and complications study at 30 years: overview. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:9-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 866] [Cited by in RCA: 1062] [Article Influence: 88.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Kelly OG, Chan MY, Martinson LA, Kadoya K, Ostertag TM, Ross KG, Richardson M, Carpenter MK, D'Amour KA, Kroon E, Moorman M, Baetge EE, Bang AG. Cell-surface markers for the isolation of pancreatic cell types derived from human embryonic stem cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29:750-756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 256] [Cited by in RCA: 259] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Kroon E, Martinson LA, Kadoya K, Bang AG, Kelly OG, Eliazer S, Young H, Richardson M, Smart NG, Cunningham J, Agulnick AD, D'Amour KA, Carpenter MK, Baetge EE. Pancreatic endoderm derived from human embryonic stem cells generates glucose-responsive insulin-secreting cells in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:443-452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1331] [Cited by in RCA: 1317] [Article Influence: 73.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Agulnick AD, Ambruzs DM, Moorman MA, Bhoumik A, Cesario RM, Payne JK, Kelly JR, Haakmeester C, Srijemac R, Wilson AZ, Kerr J, Frazier MA, Kroon EJ, D'Amour KA. Insulin-Producing Endocrine Cells Differentiated In Vitro From Human Embryonic Stem Cells Function in Macroencapsulation Devices In Vivo. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2015;4:1214-1222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 47. | Ramzy A, Thompson DM, Ward-Hartstonge KA, Ivison S, Cook L, Garcia RV, Loyal J, Kim PTW, Warnock GL, Levings MK, Kieffer TJ. Implanted pluripotent stem-cell-derived pancreatic endoderm cells secrete glucose-responsive C-peptide in patients with type 1 diabetes. Cell Stem Cell. 2021;28:2047-2061.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 222] [Article Influence: 44.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Shapiro AMJ, Thompson D, Donner TW, Bellin MD, Hsueh W, Pettus J, Wilensky J, Daniels M, Wang RM, Brandon EP, Jaiman MS, Kroon EJ, D'Amour KA, Foyt HL. Insulin expression and C-peptide in type 1 diabetes subjects implanted with stem cell-derived pancreatic endoderm cells in an encapsulation device. Cell Rep Med. 2021;2:100466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 36.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Veres A, Faust AL, Bushnell HL, Engquist EN, Kenty JH, Harb G, Poh YC, Sintov E, Gürtler M, Pagliuca FW, Peterson QP, Melton DA. Charting cellular identity during human in vitro β-cell differentiation. Nature. 2019;569:368-373. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 400] [Article Influence: 57.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Hogrebe NJ, Maxwell KG, Augsornworawat P, Millman JR. Generation of insulin-producing pancreatic β cells from multiple human stem cell lines. Nat Protoc. 2021;16:4109-4143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 28.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Izadi M, Sadr Hashemi Nejad A, Moazenchi M, Masoumi S, Rabbani A, Kompani F, Hedayati Asl AA, Abbasi Kakroodi F, Jaroughi N, Mohseni Meybodi MA, Setoodeh A, Abbasi F, Hosseini SE, Moeini Nia F, Salman Yazdi R, Navabi R, Hajizadeh-Saffar E, Baharvand H. Mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in newly diagnosed type-1 diabetes patients: a phase I/II randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2022;13:264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Issaragrisil S, Kaufman DW, Anderson T, Chansung K, Leaverton PE, Shapiro S, Young NS. The epidemiology of aplastic anemia in Thailand. Blood. 2006;107:1299-1307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Nakao S, Takamatsu H, Chuhjo T, Ueda M, Shiobara S, Matsuda T, Kaneshige T, Mizoguchi H. Identification of a specific HLA class II haplotype strongly associated with susceptibility to cyclosporine-dependent aplastic anemia. Blood. 1994;84:4257-4261. [PubMed] |

| 54. | Maciejewski JP, Follmann D, Nakamura R, Saunthararajah Y, Rivera CE, Simonis T, Brown KE, Barrett JA, Young NS. Increased frequency of HLA-DR2 in patients with paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria and the PNH/aplastic anemia syndrome. Blood. 2001;98:3513-3519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Siddiqui S, Cox J, Herzig R, Palaniyandi S, Hildebrandt GC, Munker R. Anti-thymocyte globulin in haematology: Recent developments. Indian J Med Res. 2019;150:221-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Horowitz MM. Current status of allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in acquired aplastic anemia. Semin Hematol. 2000;37:30-42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Im SH, Kim BR, Park SM, Yoon BA, Hwang TJ, Baek HJ, Kook H. Better Failure-Free Survival and Graft-versus-Host Disease-Free/Failure Free Survival with Fludarabine-Based Conditioning in Stem Cell Transplantation for Aplastic Anemia in Children. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35:e46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Killick SB, Bown N, Cavenagh J, Dokal I, Foukaneli T, Hill A, Hillmen P, Ireland R, Kulasekararaj A, Mufti G, Snowden JA, Samarasinghe S, Wood A, Marsh JC; British Society for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of adult aplastic anaemia. Br J Haematol. 2016;172:187-207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 341] [Cited by in RCA: 547] [Article Influence: 49.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Peinemann F, Grouven U, Kröger N, Pittler M, Zschorlich B, Lange S. Unrelated donor stem cell transplantation in acquired severe aplastic anemia: a systematic review. Haematologica. 2009;94:1732-1742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Bacigalupo A, Socié G, Schrezenmeier H, Tichelli A, Locasciulli A, Fuehrer M, Risitano AM, Dufour C, Passweg JR, Oneto R, Aljurf M, Flynn C, Mialou V, Hamladji RM, Marsh JC; Aplastic Anemia Working Party of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (WPSAA-EBMT). Bone marrow versus peripheral blood as the stem cell source for sibling transplants in acquired aplastic anemia: survival advantage for bone marrow in all age groups. Haematologica. 2012;97:1142-1148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Gluckman E, Devergie A, Dutreix A, Dutreix J, Boiron M, Bernard J. Bone marrow grafting in aplastic anemia after conditioning with cyclophosphamide and total body irradiation with lung shielding. Haematol Blood Transfus. 1980;25:339-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Chen J, Lee V, Luo CJ, Chiang AK, Hongeng S, Tan PL, Tan AM, Sanpakit K, Li CF, Lee AC, Chua HC, Okamoto Y. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation for children with acquired severe aplastic anaemia: a retrospective study by the Viva-Asia Blood and Marrow Transplantation Group. Br J Haematol. 2013;162:383-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S, Moss M. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1546-1554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4208] [Cited by in RCA: 4338] [Article Influence: 188.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Chiu C, Legrand M. Epidemiology of sepsis and septic shock. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2021;34:71-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 29.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Paul M, Carrara E, Retamar P, Tängdén T, Bitterman R, Bonomo RA, de Waele J, Daikos GL, Akova M, Harbarth S, Pulcini C, Garnacho-Montero J, Seme K, Tumbarello M, Lindemann PC, Gandra S, Yu Y, Bassetti M, Mouton JW, Tacconelli E, Rodríguez-Baño J. European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) guidelines for the treatment of infections caused by multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacilli (endorsed by European society of intensive care medicine). Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022;28:521-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 667] [Article Influence: 133.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Karakonstantis S, Gikas A, Astrinaki E, Kritsotakis EI. Excess mortality due to pandrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infections in hospitalized patients. J Hosp Infect. 2020;106:447-453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Saelim W, Changpradub D, Thunyaharn S, Juntanawiwat P, Nulsopapon P, Santimaleeworagun W. Colistin plus Sulbactam or Fosfomycin against Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: Improved Efficacy or Decreased Risk of Nephrotoxicity? Infect Chemother. 2021;53:128-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Leelasupasri S, Santimaleeworagun W, Jitwasinkul T. Antimicrobial Susceptibility among Colistin, Sulbactam, and Fosfomycin and a Synergism Study of Colistin in Combination with Sulbactam or Fosfomycin against Clinical Isolates of Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. J Pathog. 2018;2018:3893492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Zheng G, Huang R, Qiu G, Ge M, Wang J, Shu Q, Xu J. Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicles: regenerative and immunomodulatory effects and potential applications in sepsis. Cell Tissue Res. 2018;374:1-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Doi K. How to replicate the complexity of human sepsis: development of a new animal model of sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:2722-2723. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Galstian GM, Parovichnikova EN, Makarova PM, Kuzmina LA, Troitskaya VV, Gemdzhian E, Drize NI, Savchenko VG. The Results of the Russian Clinical Trial of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells (MSCs) in Severe Neutropenic Patients (pts) with Septic Shock (SS) (RUMCESS trial). Blood. 2015;126:2220. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | İzci F, Ture Z, Dinc G, Yay AH, Eren EE, Bolat D, Gönen ZB, Ünüvar GK, Yıldız O, Aygen B. The efficacy of mesenchymal stem cell treatment and colistin-fosfomycin combination on colistin-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii sepsis model. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2023;42:1365-1372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Lawn JE, Cousens S, Zupan J; Lancet Neonatal Survival Steering Team. 4 million neonatal deaths: when? Lancet. 2005;365:891-900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2275] [Cited by in RCA: 2418] [Article Influence: 115.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Cotten CM. Adverse consequences of neonatal antibiotic exposure. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2016;28:141-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Nagamura-Inoue T, He H. Umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells: Their advantages and potential clinical utility. World J Stem Cells. 2014;6:195-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 258] [Cited by in RCA: 322] [Article Influence: 26.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 76. | Ren Z, Zheng X, Yang H, Zhang Q, Liu X, Zhang X, Yang S, Xu F, Yang J. Human umbilical-cord mesenchymal stem cells inhibit bacterial growth and alleviate antibiotic resistance in neonatal imipenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Innate Immun. 2020;26:215-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Sutton MT, Fletcher D, Ghosh SK, Weinberg A, van Heeckeren R, Kaur S, Sadeghi Z, Hijaz A, Reese J, Lazarus HM, Lennon DP, Caplan AI, Bonfield TL. Antimicrobial Properties of Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Therapeutic Potential for Cystic Fibrosis Infection, and Treatment. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016:5303048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Zakrzewski W, Dobrzyński M, Szymonowicz M, Rybak Z. Stem cells: past, present, and future. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10:68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 937] [Cited by in RCA: 1051] [Article Influence: 150.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (35)] |

| 79. | Brown G. Introduction and Classification of Leukemias. Methods Mol Biol. 2021;2185:3-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Schultz KR, Carroll A, Heerema NA, Bowman WP, Aledo A, Slayton WB, Sather H, Devidas M, Zheng HW, Davies SM, Gaynon PS, Trigg M, Rutledge R, Jorstad D, Winick N, Borowitz MJ, Hunger SP, Carroll WL, Camitta B; Children’s Oncology Group. Long-term follow-up of imatinib in pediatric Philadelphia chromosome-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia: Children's Oncology Group study AALL0031. Leukemia. 2014;28:1467-1471. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 299] [Cited by in RCA: 356] [Article Influence: 29.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Fitch SR, Kapeni C, Tsitsopoulou A, Wilson NK, Göttgens B, de Bruijn MF, Ottersbach K. Gata3 targets Runx1 in the embryonic haematopoietic stem cell niche. IUBMB Life. 2020;72:45-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Wang F, Zhao W, Kong N, Cui W, Chai L. The next new target in leukemia: The embryonic stem cell gene SALL4. Mol Cell Oncol. 2014;1:e969169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Suzuki D, Kobayashi R, Hori D, Kishimoto K, Sano H, Yasuda K, Kobayashi K. Stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia with pulmonary and cerebral mucormycosis. Pediatr Int. 2016;58:569-572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Haake K, Ackermann M, Lachmann N. Concise Review: Towards the Clinical Translation of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Blood Cells-Ready for Take-Off. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2019;8:332-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Sarkar E, Khan A. Erratic journey of CRISPR/Cas9 in oncology from bench-work to successful-clinical therapy. Cancer Treat Res Commun. 2021;27:100289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Mitra S, Sarker J, Mojumder A, Shibbir TB, Das R, Emran TB, Tallei TE, Nainu F, Alshahrani AM, Chidambaram K, Simal-Gandara J. Genome editing and cancer: How far has research moved forward on CRISPR/Cas9? Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;150:113011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Ma L, Yang S, Peng Q, Zhang J, Zhang J. CRISPR/Cas9-based gene-editing technology for sickle cell disease. Gene. 2023;874:147480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Bahari M, Mokhtari H, Yeganeh F. Stem Cell Therapy, the Market, the Opportunities and the Threat. Int J Mol Cell Med. 2023;12:310-319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Shang Z, Wanyan P, Zhang B, Wang M, Wang X. A systematic review, umbrella review, and quality assessment on clinical translation of stem cell therapy for knee osteoarthritis: Are we there yet? Stem Cell Res Ther. 2023;14:91. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Brianna, Ling APK, Wong YP. Applying stem cell therapy in intractable diseases: a narrative review of decades of progress and challenges. Stem Cell Investig. 2022;9:4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Centeno CJ, Al-Sayegh H, Freeman MD, Smith J, Murrell WD, Bubnov R. A multi-center analysis of adverse events among two thousand, three hundred and seventy two adult patients undergoing adult autologous stem cell therapy for orthopaedic conditions. Int Orthop. 2016;40:1755-1765. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Lovell-Badge R, Anthony E, Barker RA, Bubela T, Brivanlou AH, Carpenter M, Charo RA, Clark A, Clayton E, Cong Y, Daley GQ, Fu J, Fujita M, Greenfield A, Goldman SA, Hill L, Hyun I, Isasi R, Kahn J, Kato K, Kim JS, Kimmelman J, Knoblich JA, Mathews D, Montserrat N, Mosher J, Munsie M, Nakauchi H, Naldini L, Naughton G, Niakan K, Ogbogu U, Pedersen R, Rivron N, Rooke H, Rossant J, Round J, Saitou M, Sipp D, Steffann J, Sugarman J, Surani A, Takahashi J, Tang F, Turner L, Zettler PJ, Zhai X. ISSCR Guidelines for Stem Cell Research and Clinical Translation: The 2021 update. Stem Cell Reports. 2021;16:1398-1408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 226] [Article Influence: 45.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Cote DJ, Bredenoord AL, Smith TR, Ammirati M, Brennum J, Mendez I, Ammar AS, Balak N, Bolles G, Esene IN, Mathiesen T, Broekman ML. Ethical clinical translation of stem cell interventions for neurologic disease. Neurology. 2017;88:322-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Bredenoord AL, Clevers H, Knoblich JA. Human tissues in a dish: The research and ethical implications of organoid technology. Science. 2017;355:eaaf9414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 213] [Article Influence: 23.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Ishii T, Pera RA, Greely HT. Ethical and legal issues arising in research on inducing human germ cells from pluripotent stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2013;13:145-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Bentzinger CF, Wang YX, Rudnicki MA. Building muscle: molecular regulation of myogenesis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4:a008342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 617] [Cited by in RCA: 841] [Article Influence: 60.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Yokoyama S, Asahara H. The myogenic transcriptional network. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:1843-1849. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Tedesco FS, Dellavalle A, Diaz-Manera J, Messina G, Cossu G. Repairing skeletal muscle: regenerative potential of skeletal muscle stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:11-19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 446] [Cited by in RCA: 475] [Article Influence: 29.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Barreiro E, Tajbakhsh S. Epigenetic regulation of muscle development. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2017;38:31-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Das BC, Tyagi A. Stem Cells: A Trek from Laboratory to Clinic to Industry. In: Verma AS, Singh A, editors. Animal Biotechnology. CA: Academic Press, 2014: 425-450. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Pereira M, Birtele M, Rylander Ottosson D. Direct reprogramming into interneurons: potential for brain repair. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2019;76:3953-3967. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/