Published online Mar 18, 2026. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v16.i1.114367

Revised: September 27, 2025

Accepted: November 26, 2025

Published online: March 18, 2026

Processing time: 119 Days and 16.9 Hours

Kidney transplantation (KT) accounts for nearly three-fourths of organ transplants in India, with living donors contributing to 82% of cases. Induction immunosuppression is essential to optimize initial immunosuppression, reduce acute rejections, and enable tailored use of maintenance agents. Rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin (rATG) and interleukin-2 receptor anatagonists (IL-2RA/IL-2RBs) are the most widely used induction therapies. However, data on induction practices across India are limited. To evaluate induction immunosuppression practices across KT centers in India and establish a consensus for different subsets of KT recipients. A nationwide online survey was conducted by the Indian Society of Organ Transplantation (ISOT) among its members (400 KT centers). Responses were analyzed to assess induction practices across diverse donor types, age groups, and immunological risk profiles. Heterogeneity in practices prompted consensus building using a modified Delphi process. Literature review and expert panel discussions (April 2024) were followed by structured voting, and 16 consensus statements were finalized. Of 400 centers approached, 254 participated. rATG was the most commonly used induction therapy, followed by IL-2RBs; alemtuzumab was least used. Significant heterogeneity was observed in type, dose, and duration of induction therapy. Consensus recommendations were framed: rATG for high immunological risk recipients and deceased donor KTs; IL-2RB or low-dose rATG for low immunological risk; rituximab in ABO-incompatible KTs; and tailoring based on age, diabetes, donor type, infection risk, and affordability. This first ISOT consensus provides 16 India-specific statements on induction therapy in KT. It emphasizes risk-stratified, evidence-informed, and context-appropriate induction strategies, supporting standardization of care across the country.

Core Tip: Kidney transplantation is the most common solid organ transplantation in India, yet induction immunosuppression practices vary widely across centers. The Indian Society of Organ Transplantation (ISOT) conducted a nationwide survey and identified significant heterogeneity in induction therapy choice, dose, and duration. Through a structured Delphi consensus, ISOT developed 16 statements to guide practice. Rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin (rATG) remains the preferred induction for high immunological risk and deceased donor recipients, while interleukin-2 receptor anatagonists or low-dose rATG is suitable for low-risk cases. Rituximab is recommended for ABO-incompatible transplants. These India-specific guidelines provide a standardized framework to optimize patient outcomes and rationalize induction therapy.

- Citation: Kute VB, Balwani MR, Shrimali JB, Pasari A, Kher V, Patel MP, Chafekar D, Guditi S, Das P, Siddaiah GM, Godara SM, Bhargava V, Gupta A, Ramteke V, Deshpande N, Tolani P, Prasad N, Patil RK, Mohanka R, Mahajan S, Sharma S, Banerjee S, Engineer DP, Agarwal D, Kashiv P, Lahiri A, Khullar D, Srivastava A. Induction therapy in kidney transplant recipients: A consensus statement of Indian Society of Organ Transplantation. World J Transplant 2026; 16(1): 114367

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3230/full/v16/i1/114367.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v16.i1.114367

Kidney transplants (KTs) account for 75% of organ transplants in India[1]. All KT recipients (KTRs) need induction immunosuppressive therapy given perioperatively[2,3]. Induction therapy depletes or modulates the T-cell responses at the time of antigen (KT) presentation in the recipient. Thus, it helps improve the efficacy of immunosuppression, thereby reducing the incidence and severity of acute rejections and by balancing the use of other immunosuppressive therapies, such as calcineurin inhibitors, antimetabolites or corticosteroids[2,4].

Induction therapy in KT mainly consists of biological T-cell (lymphocyte) depleting antibodies, such as rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin (rATG) (thymoglobulin), anti-human-T-lymphocyte immunoglobulin (ATLG), humanized anti-CD52 monoclonal antibodies (mAb) (alemtuzumab); and non-lymphocyte depleting agents such as mAb directed against the interleukin 2 receptor (IL2R) or IL2R blockers (IL-2RB/IL-2RA) (basiliximab); and preconditioning agent such as rituximab used for ABO-incompatible KT (ABOiKT)[2,3,5-7].

“The Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO)” guidelines recommend starting a combination immunosuppressive therapy before or at the time of KT[2]. There are no guidelines from India on the choice of induction therapy in KT, and the KDIGO guidelines may not be applicable in India as the risk assessment criteria in the KDIGO guidelines were based on clinical evidence in the Caucasian population and the majority of KTs in the West are from deceased donors[4]. Further, the KDIGO guidelines were published during a time when cyclosporine immunosuppression was practiced, as opposed to tacrolimus-based immunosuppression, which is practiced today[4]. Revised KDIGO guidelines were not published when this consensus was developed. Moreover, literature on the induction practices followed in India for various subsets of KTRs is lacking.

Hence, the Indian Society of Organ Transplant (ISOT) conducted a pan-India online survey with its members to understand the practice patterns of induction therapies used for the different types of KTRs across different age groups, with different immunological risk profiles and receiving kidneys from different types of donors (living, deceased, ABOiKT, etc.). As the survey showed great heterogeneity in the induction therapy practiced across KT centers in India, hence, ISOT decided to build a consensus on induction practices in KT in India. The need for a consensus on induction therapy in KT based on patient profiles seen in routine clinical practice arose as there are no guidelines on this aspect of KTs, and it would help the younger professionals involved in KTs before gaining experience in a large KT patient population.

Three members of the ISOT team, along with the medical writing team, deliberated on various questions regarding type, dose, and duration of induction therapy across all types of KT recipients that would help understand the decision-driving factors. The survey originally consisted of 35 questions; nine were considered repetitive or likely to generate ambiguous responses and hence discarded; finally, 26 questions on type, dose, and duration of induction therapy in KT were included. Of these five questions were on the number of KTs carried out in the transplant center in the last decade (2013-2023), last year (2023), and from different types of donors (living, deceased, ABOiKT); four questions were about most to least common induction therapy practiced in the transplant center; six questions were on the choice of induction therapy in KT recipients from living donors (based on the age of recipient and diabetes status); four questions were on choice of induction therapy in recipients from deceased donors [(based on standard and expanded criteria, acute kidney injury (AKI), and infections]; three questions were on ABOiKT; two questions were on factors influencing decisions on choice of induction therapy or no induction therapy; two questions were on choice of induction therapy by immunological risk stratification.

The questions around the choice of induction therapy had six options: RATG, IL-2RB (basiliximab), ATLG, rituximab, alemtuzumab, and no induction. Once a user selected a type of therapy, the respondent was prompted to enter the most common dose and duration used in the respondent’s center. The questions around factors influencing the choice of induction therapy included 11 factors to consider before choosing an induction therapy, six factors to consider before choosing whether to give or not give induction therapy, and 11 factors to consider before choosing an induction therapy in ABOiKT transplants. The user had the option to choose multiple factors for each question.

The online survey was designed using the Microsoft Survey Form, and a respondent could not submit the form unless all 26 questions were answered. The survey was first piloted with 10 ISOT members specializing in organ donation and transplantation who were not a part of the core team. The survey link was sent to ISOT members across India via email and WhatsApp on February 26, 2024. A reminder to complete the surveys with the survey link was sent weekly. The survey was closed on March 17, 2024 and results analyzed. The results were presented as percentages.

The survey results showed great heterogeneity in responses regarding the type, dose, and duration of induction therapy. Hence, a decision was made to develop an India-specific consensus on induction therapy in KT. This work was designed and conducted as a formal national consensus statement and guideline rather than as a traditional observational study.

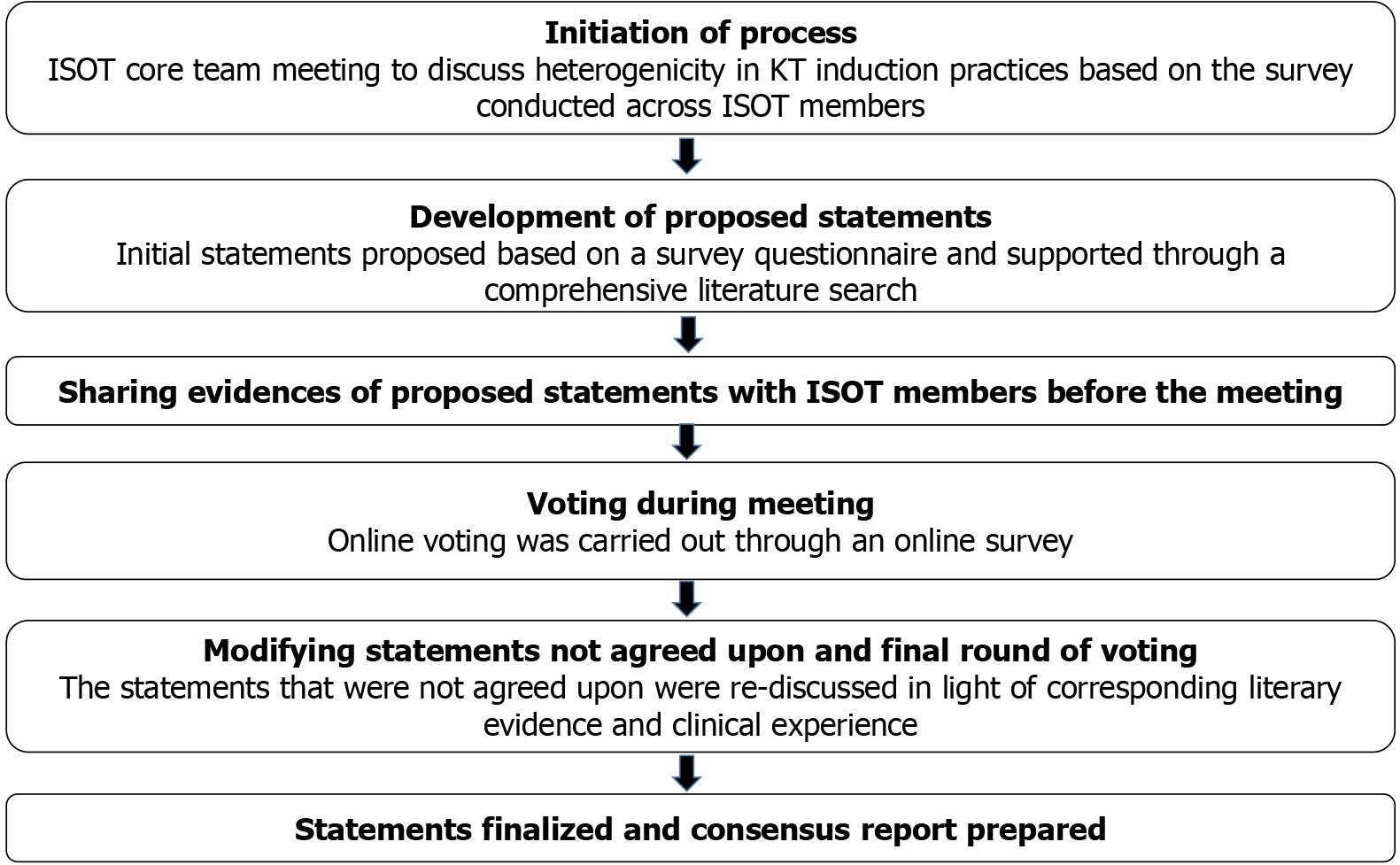

A modified Delphi process was used to develop the consensus (Figure 1)[8]. First, a comprehensive literature search was carried out on MEDLINE and Google Scholar to identify Indian and international literature and guidelines on induction therapy in KT. Based on the survey questionnaire and subsequent literature review, consensus statements were formulated before the advisory board meeting on April 27-28, 2024. The consensus statements and supporting literature were circulated with the ISOT members before the meeting.

An expert panel of 15-20 ISOT members was created before the advisory board meeting to deliberate on the consensus statements during the meeting. Each consensus statement and its supporting literature were presented during the meeting. This was followed by a detailed discussion among the panel members, which the Chair mediated. The experts also shared their clinical experience during the discussions. After discussing each statement, four voting options were used: “Strongly agree”, “Agree”, “Disagree”, and “Strongly Disagree”. A statement for which ≥ 70% of ISOT members voted as “Strongly Agree” or “Agree” was accepted as “Consensus”. Any statement for which ≥ 70% of ISOT members voted as “Disagree” or “Strongly Disagree” was further discussed and revised as per suggestions. A second set of voting was carried out for these statements. If ≥ 70% of ISOT members voted for the statement, it was accepted as “Consensus”.

At the time of this survey, ISOT had 2000 members with multidisciplinary expertise in intensive care, organ donation and transplantation, immunology, and pathology. Of these, only 1200 members involved in clinical care of patients were eligible to participate in the survey. These 1200 members were part of 400 KT centers across India. Members of each transplant center collectively filled out the form, so there was one response per center. Of the 400 centers contacted to fill out the survey, 254 centers filled out the survey. All 254 surveys were used to analyze the induction therapy practice patterns in KT recipients across India.

Between 2013 and 2023, 68% of the centers had carried out < 500 KTs, and 16.5% had carried out > 1000 KTs. In 2023, 13.4% had carried out < 10 KTs; 44.9% of the centers had carried out 11 KTs to 50 KTs; and 15% had carried out > 200 KTs. The majority of transplants occurred from living donors (81%-100%; 59.4% of the centers); in 61% of centers < 10% of total transplants were from deceased donors; in 66% of centers < 10% of total transplants from ABOiKT donors.

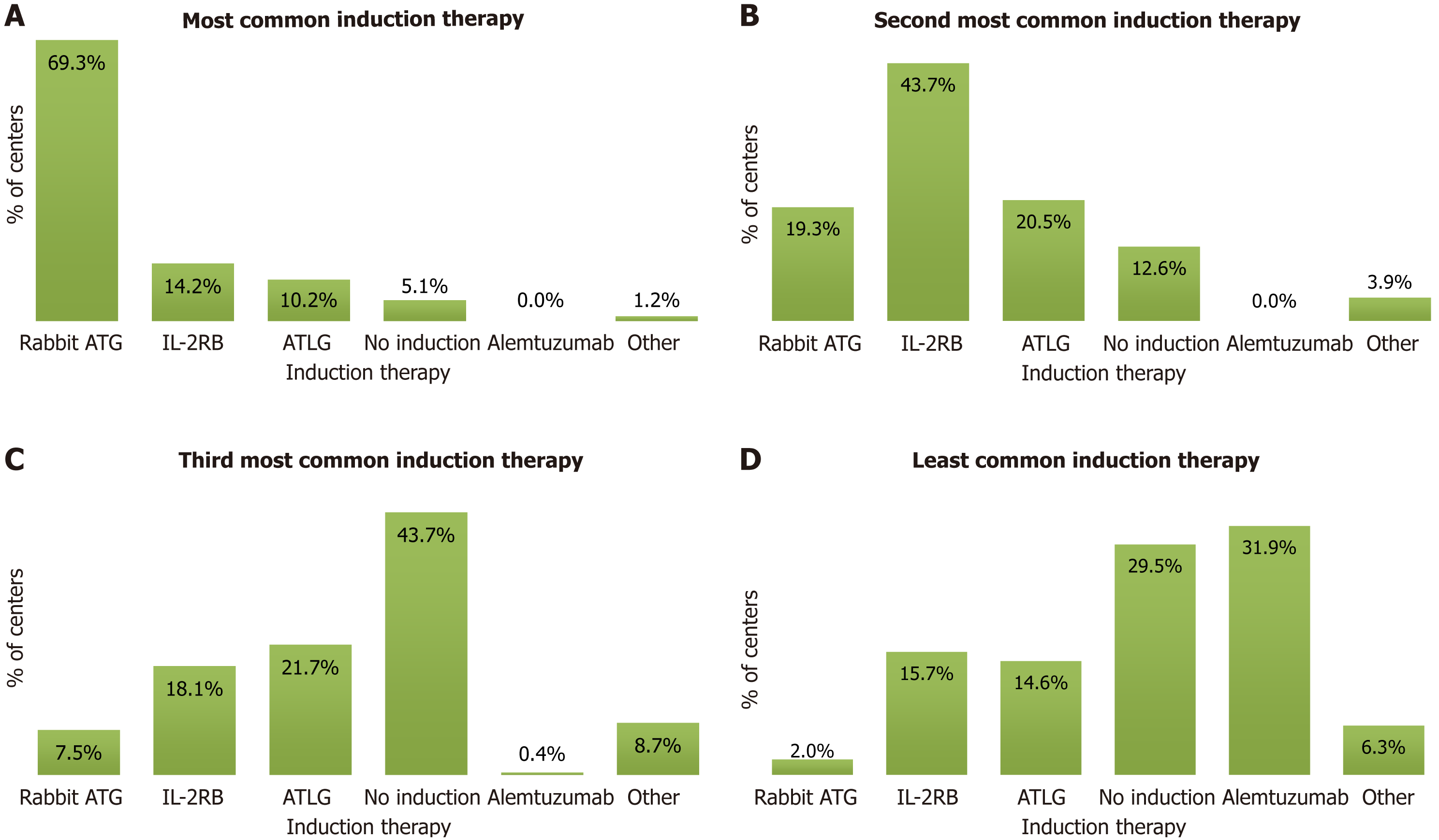

rATG was the most common overall induction therapy practiced in the centers. Studies from the United States have also shown that rATG was the most common induction therapy used for KT in the United States[9,10].

The survey responses showed that IL-2RB was the second most common induction therapy, and giving no induction was the third most common practice. Alemtuzumab was the least common induction therapy practiced by the specialists. The survey responses on the use of induction therapies are presented in Figure 2.

Since rATG, IL-2RB, and giving no induction were India’s three most common induction practices, the experts considered these while developing the consensus statements.

The survey showed that all centers used IL-2RB (basiliximab) in a standard dose of 20 mg on days 0 (day of KT) and day 4 (posttransplant). Basiliximab (IL-2RB), a chimeric antibody, can suppress T cells for up to 25 days to 35 days[11]. Two 20 mg doses of basiliximab administered intravenously were approved in 1998 for the prevention of acute rejection in kidney and liver transplantation[7,11]. For pediatric patients weighing < 35 kg, 10 mg may be used.

Statement 1: The experts unanimously accepted that basiliximab should be administered at 20 mg on days 0 (day of KT) and day 4 (posttransplant).

The survey showed that despite the frequent use of rATG across different subsets of KTRs, the dose of rATG used by the centers varied from a single dose of 0.2 mg/kg to 10 mg/kg (Table 1)[12-19].

| Type of recipients with specialists using rATG as preferred dose unless otherwise specified | Lowest dose (mg/kg in single dose or given twice if required) | Highest dose (mg/kg in single dose) | Using 1.5 mg/kg dose (in single dose or fraction of cumulative dose)1, % |

| High immunological risk | 0.2 | 6 | 10.6 (27/254) |

| Low immunological risk3 | 0.25 | 3 | 4.7 (12/254) |

| ABOiKT | 0.5 | 6 | 7.9 (20/254) |

| Adults with low immunological risk3 | 0.25 | 5 | 7.5 (19/254) |

| Adults with high immunological risk | 0.25 | 6 | 11.4 (29/254) |

| Elderly | 0.5 | 4 | 5.1 (13/254) |

| Adolescents | 0.4 | 5 | 7.1 (18/254) |

| Paediatric | 0.2 | 5 | 9.1 (23/254) |

| Kidney from living donor with diabetes | 0.25 | 10 | 11.4 (29/254) |

| Kidney from SCD | 0.2 | 7-8 | 8.3 (21/254) |

| Kidney from ECD | 0.2 | 6 | 7.9 (20/254) |

| Kidney from deceased donor with AKI | 0.5 | 5 | 9.1 (23/254) |

| Kidney from deceased donor with infection | 0.5 | 32 | 6.7 (17/254) |

The experts deliberated on the available evidence and their clinical experience and unanimously suggested two broad rATG dosing strategies. However, the experts cautioned that the rATG dose may be further modified based on the individual risk profiles of the KTRs.

Statement 2: A 3 mg (2.5 to 3.5) mg/kg dose in single or divided doses was suggested for higher-risk immunological profiles. A 1.5 mg/kg to 2 mg/kg dose in single or divided doses was suggested for lower immunological risk assessment profiles.

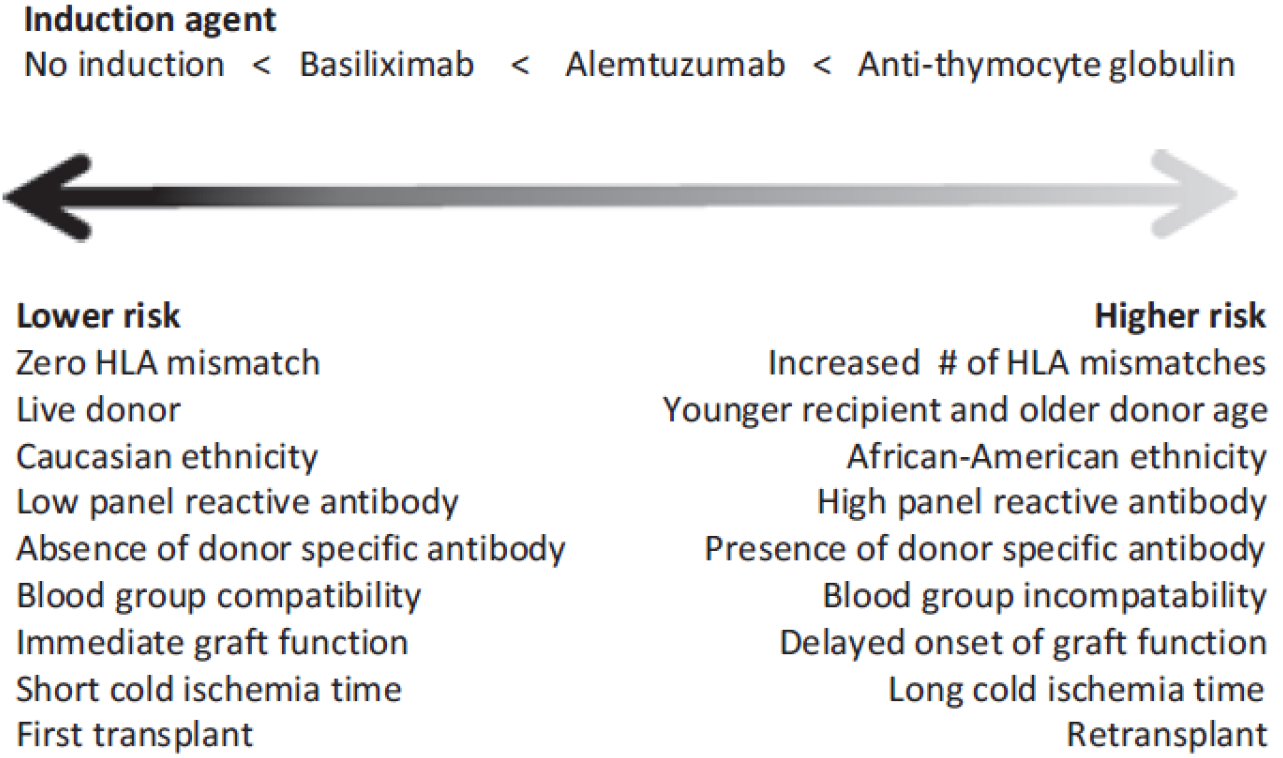

The risk stratification assessment criteria in KDIGO guidelines were stratified into three levels based on universal agreement (A), majority agreement (B), and evidence from a single study (C) (Table 2); the majority of the risk criteria fell into category B[2]. The Indian risk stratification used all the criteria suggested by KDIGO guidelines except ethnicity but stratified them as having strong, moderate, mild, or no effect on acute rejection (Table 3)[4,20]. Clinical practice in India has also emphasised the role of infection status when tailoring immunosuppression in transplant recipients[20]. Table 4 provides the relative importance of pretransplant risk factors for acute rejection after KTs, derived from a review article[21,22]. KTRs with the lowest immunological risk may not require induction therapy, while IL-2RB may be preferred in lower immunological risk profile KTRs, and rATG induction therapy is preferred in those with the highest immunological risk (Figure 3)[7].

| Universal agreement (A) | Majority agreement (B) | Evidence from single study (C) |

| > 1 HLA mismatches | Younger recipient age – no age threshold; older donor age – no age threshold; Black ethnicity (in the United States); PRA > 0%; presence of DSA; blood group incompatibility; delayed onset of graft function, especially with ECD | Cold ischemia time > 24 hours |

| Strong | Moderate | Mild | No effect | |

| Donor-related factors | Donor-recipient age matching | Older donor age | - | Deceased donor; ECD/cause of death/non-heart beating1; diabetes/hypertension, polycystic kidney disease; HCV status |

| Recipient-related factors | Donor-recipient age matching; HLA mismatch; presence of anti-HLA antibodies; presence of pre-transplant DSA and DSA titer | PRA | Re-transplantation | - |

| Transplant-related factors | Delayed graft function | - | Cold ischemia time | CMV/HIV/HCV infection1; gender; high BMI |

| Risk factor | Reason for considering | Importance |

| Younger recipient age | Stronger immune response | ++ |

| Adolescent recipient | Higher risk for nonadherence | +++ |

| Donor age | Older organs: Higher immunogenicity | + |

| Recipient gender | Males: Fewer rejections | + |

| Ethnicity | African Americans: Significantly higher risk | +++ |

| Deceased vs living donor | Insignificant differences. DD: Insignificant differences between donation after cardiac vs brain death, or ECD vs SCD | + |

| Previous-transfusion | low immunologic responder: If unsensitized despite previous transfusion | + |

| Previous-transplantation | Unsensitized recipient: No significant increase in risk; early loss of previous graft to immunological causes → increased risk of next graft rejection | ++1 |

| Previous-pregnancy | Increasing risk with successive pregnancies | ++ |

| PRA > 0% (HLA antibodies) | Includes both historic and current PRA level HLA antibodies class I and/or class II | +++ |

| Preformed HLA, DSA (> 500 MFI) | Having no preformed HLA DSA at transplant: Low immunological risk. Low noncytotoxic HLA antibodies level: Intermediate risk. Required de novo HLA DSA posttransplant monitoring | ++++ |

| Sensitized patients after desensitization | Increased AMR risk, which may persist after desensitization in DSA-positive patients: Negative cytotoxicity and negative flow cross-match (low risk); flow cross-match (moderate increase in risk); positive cytotoxicity (profound increase in risk) | ++/+++ |

| HLA mismatch | Marked and well-documented effect on cellular and antibody-mediated rejection. Particularly pronounced for HLA DR mismatch | +++ |

| CMV1 mismatch | No association between CMV mismatch and acute rejection due to CMV prophylaxis | – |

| EBV1 mismatch | No effect per se on acute rejection | – |

| Cold ischemia time | Less important with current shorter ischemic times | + |

| Delayed graft function | Delayed function may prompt changes to the planned protocol in the first few days posttransplant | +++ |

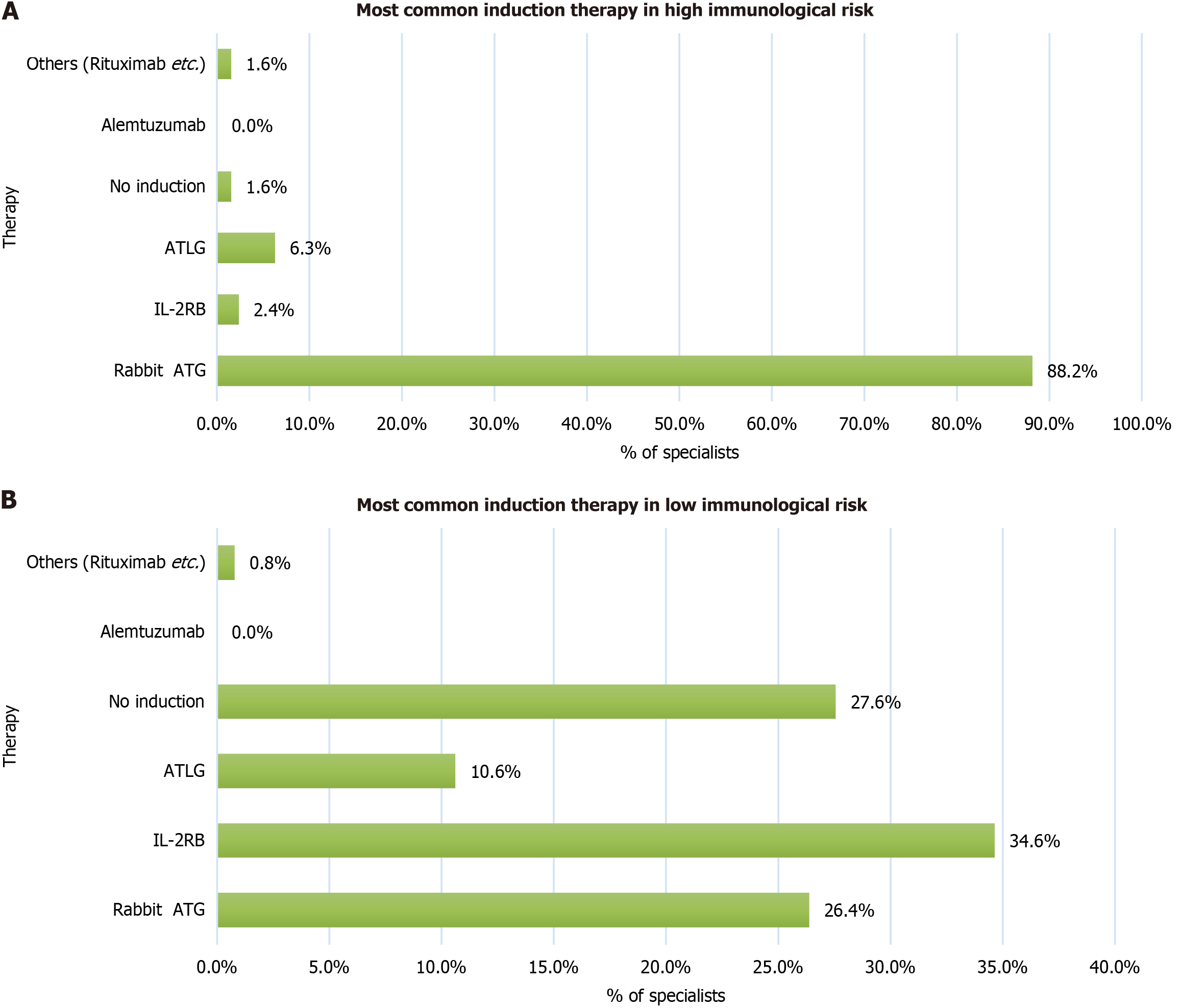

Survey results: Preferred induction therapy in KTRs with high immunological risk. rATG was used as the induction therapy by 88.2% of specialists in KTRs with high immunological risk. However, 11.8% of centers used other induction therapies in recipients with high immunologic risk is shown in Figure 4. Similar findings on the effectiveness of rATG in high-risk recipients have been reported in clinical studies[23-25].

Preferred induction therapy in adult (> 18 years to < 65 years) LDKTRs with high immunological risk. In adult recipients with high immunological risk, 83.1% of the specialists used rATG as the induction therapy. However, 16.9% of centers used other induction therapies in recipients with high immunologic risk as shown in Figure 4. The role of rATG in adult high-risk recipients has also been supported by randomized trials and long-term registry data[26-28].

Statement 3: ISOT suggests that rATG should be used as induction therapy in high immunologic risk (for example, retransplant, sensitized) recipients of KT from living donors in a total dose of 3 (2.5 to 3.5) mg/kg in single or divided doses. The above statement was accepted as consensus with voting results: Strongly agree (60.9%), agree (26.1%), neutral (13%), disagree/strongly disagree (0%).

Statement 4: ISOT suggests that rATG should be used as induction therapy in adults (> 18 years to < 65 years) with high immunologic risk receiving KT from a living donor in a dose of 3 (2.5 to 3.5) mg/kg in single or divided doses.

The above statement was accepted as consensus with voting results: Strongly agree (44%), agree (56%), neutral (0%), disagree/strongly disagree (0%).

Survey results: Preferred induction therapy in KTRs with low immunological risk. In recipients with low immunological risk, 34.6% of centers used IL-2RB, 27.6% used no induction therapy, and 26.4% used rATG as the induction therapy. Similar variations in practice have been reported in international and Indian studies[29-34].

Preferred induction therapy in adults LDKTRs (> 18 years to < 65 years) with low immunological risk. IL-2RB was the most common induction therapy used by 34.3% of the centers in adult recipients with low immunological risk, followed by rATG by 28.3% of centers. These findings are consistent with additional published evidence[35-39].

Statement 5: ISOT suggests that IL-2RB or low-dose rATG should be used as induction therapy in low-immunologic-risk recipients of KT from living donors. IL-2RB should be used in a standard dose of 20 mg, given in two doses on day 0 and day 4. rATG should be given in a total dose of 1.5 mg/kg to 2 mg/kg in single or divided doses. The above statement was accepted as consensus with voting results: Strongly agree (27.3%), agree (50%), neutral (9.1%), disagree (9.1%), strongly disagree (4.5%).

Statement 6: ISOT suggests that IL-2RB or low dose rATG should be used as induction therapy in adult (> 18 years to < 65 years) with low immunologic risk receiving KT from living donor. IL-2RB should be used in a standard dose of 20 mg two doses on day 0 and day 4. rATG should be given in a total dose of 1.5 mg/kg to 2 mg/kg in single or divided doses. The above statement was accepted as consensus with voting results: Strongly agree (40%), agree (36%), neutral (12%), disagree (12%), strongly disagree (0%).

Survey results: Preferred induction therapy in ABO-incompatible KTRs. The survey indicated heterogeneity in the induction practices for ABO-incompatible kidney transplantation, which is in line with international and Indian reports[40-47].

Statement 7: ISOT suggests that rituximab should be given in a single dose of 200 mg for ABOiKT. The above statement was accepted as consensus with voting results: Strongly agree (48.1%), agree (29.6%), neutral (14.8%), disagree (7.4%), strongly disagree (0%).

Survey results: Preferred induction therapy in elderly (> 65 years) LDKTRs. rATG was the induction therapy used by 31.9% of the centers in elderly recipients. IL-2RB was used by 28% of the centers, and 20.4% used the same induction therapy as used in adults (did not change induction therapy because of age). Similar concerns about induction in elderly recipients have been described internationally[48-50].

Preferred induction therapy in adolescents (> 12 years to < 18 years) LDKTRs. rATG was used as the induction therapy by 49.6% of the specialists in adolescent recipients; 20% of the specialists used the same induction therapy as that for adults; and 19.7% used IL-2RB. Published reports have evaluated outcomes with rATG and basiliximab in younger age groups[51-53].

Preferred induction therapy in paediatric (< 12 years) LDKTRs. In pediatric recipients, 46.5% of the centers used rATG as the induction therapy; 19.3% used IL-2RB, and 23.6% used the same induction therapy as in adults (did not change induction therapy because of age). Evidence from paediatric transplantation also supports the use of rATG or IL-2RB[51-53].

Statement 8: ISOT suggests that the induction therapy used in adults should also be used in elderly (> 65 years) recipients of KT from living donors according to their risk profile. There should be no change in induction therapy in the elderly because of age. The dose of the induction therapy should be according to the immunological profile, as followed for adults. The above statement was accepted as consensus with voting results: Strongly agree (32%), agree (52%), neutral (12%), disagree (0%), strongly disagree (4%).

Statement 9: ISOT suggests that rATG should be used as induction therapy in adolescent (12 years to < 18 years) recipients of KT from living donors. The dose of the induction therapy should be according to the immunological profile as followed for adults. The above statement was accepted as consensus with voting results: Strongly agree (34.8%), agree (52.2%), neutral (13%), disagree (0%), strongly disagree (0%).

Statement 10: ISOT suggests that rATG should be used as induction therapy in paediatric (< 12 years) recipients of KT from living donors. The dose of the induction therapy should be according to the immunological profile as followed for adults. The above statement was accepted as consensus with voting results: Strongly agree (34.8%), agree (43.5%), neutral (21.7%), disagree (0%), strongly disagree (0%).

Survey results: Preferred induction therapy in LDKTRs with diabetes. rATG was used as the induction therapy by 46.9% of the centers in LDKTRs with diabetes; 19.3% used IL-2RB; and 18.1% selected the induction therapy based on immunological risk assessment. The importance of diabetes and new-onset diabetes after transplantation in guiding post-transplant outcomes has been highlighted in prior studies[54-56].

Statement 11: ISOT suggests that in recipients with diabetes, strict blood sugar control is mandatory. Diabetes as a co-morbidity should not dictate the change in the use or dose of either rATG or IL-2RB. The dose of induction should be as per the immunologic risk profile of the KT recipient. The above statement was accepted as consensus with voting results: Strongly agree (45.5%), agree (40.9%), neutral (13.6%), disagree/strongly disagree (0%).

Survey results: Preferred induction therapy in recipients of kidney from deceased donors. Recipients of standard criteria deceased donor; recipients of expanded criteria deceased donor (ECD). Similar practice patterns with rATG and basiliximab have been reported in Indian and international studies[57-59].

Statement 12: ISOT suggests that rATG should be used as induction therapy in recipients of kidney from deceased donors (both standard criteria and expanded criteria) in a total dose of 2 mg/kg to 3 mg/kg in single or divided doses. The above statement was accepted as consensus with voting results: Strongly agree (38.1%), agree (38.1%), neutral (14.3%), disagree (9.5%), strongly disagree (0%).

Survey results: Preferred induction therapy in KTRs from deceased donor with AKI. rATG was used as the induction therapy by 72.4% of the centers in KT recipients from deceased donors with AKI.

Statement 13: ISOT suggest that induction used in deceased donor kidney transplant (DDKT) needs no change just because of presence of AKI. rATG should be used in a total dose of 3 (2.5 to 3.5) mg/kg in single or divided doses. The above statement was accepted as consensus with voting results: Strongly agree (33.3%), agree (38.1%), neutral (19.0%), disagree (4.8%), strongly disagree (4.8%).

Survey results: Preferred induction therapy in KTRs from deceased donors with potential infections. When risk of infection was present, many centres preferred to reduce the intensity of induction by using IL-2RB or low-dose rATG. Similar approaches have been described in Indian cohorts, infection-focused studies, and South Asian transplant guidelines[60-64].

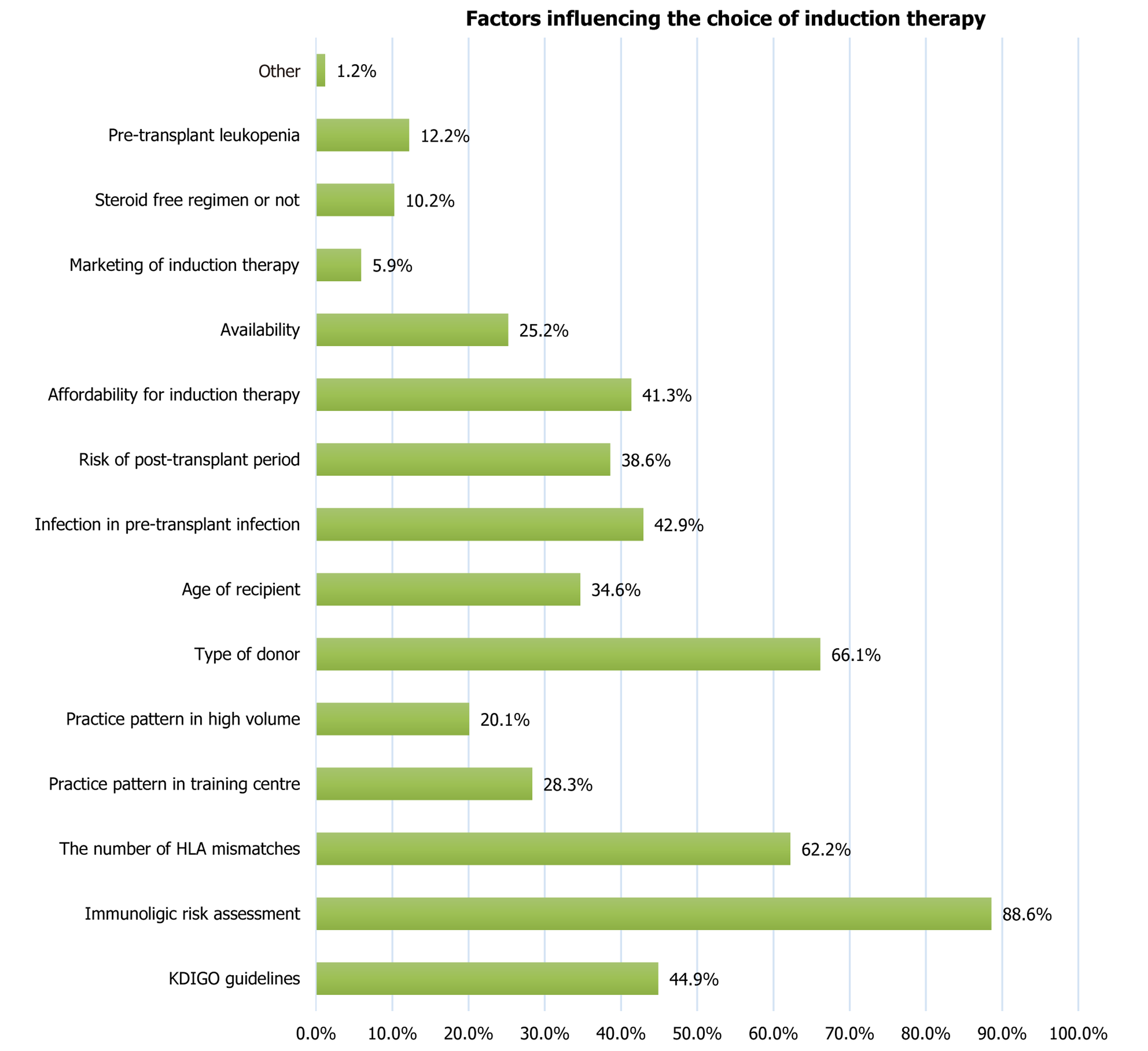

Statement 14: ISOT suggests that IL-2RB or low dose rATG should be used as induction therapy in recipients of kidney from deceased donors with potential infections. IL-2RB should be used in a standard dose of 20 mg two doses on day 0 and day 4. rATG should be given in a total dose of 1.5 mg/kg to 2 mg/kg in single or divided doses. The above statement was accepted as consensus with voting results: Strongly agree (24.0%), agree (33.0%), neutral (19.0%), disagree (24.0%), strongly disagree (0%). Factors considered by the centers before choosing the induction therapy are captured in Figure 5. Anti-thymocyte globulin dose was modified according to white blood cell and platelet count (Table 5)[16].

| Lab value | ATG dose | |

| WBC | 2000/mm3 to 3000/mm3 | Dose halved |

| < 2000/mm3 | ATG stopped | |

| Platelet | < 75000/mm3 but > 50000/mm3 | Dose halved |

| < 50000/mm3 | ATG stopped |

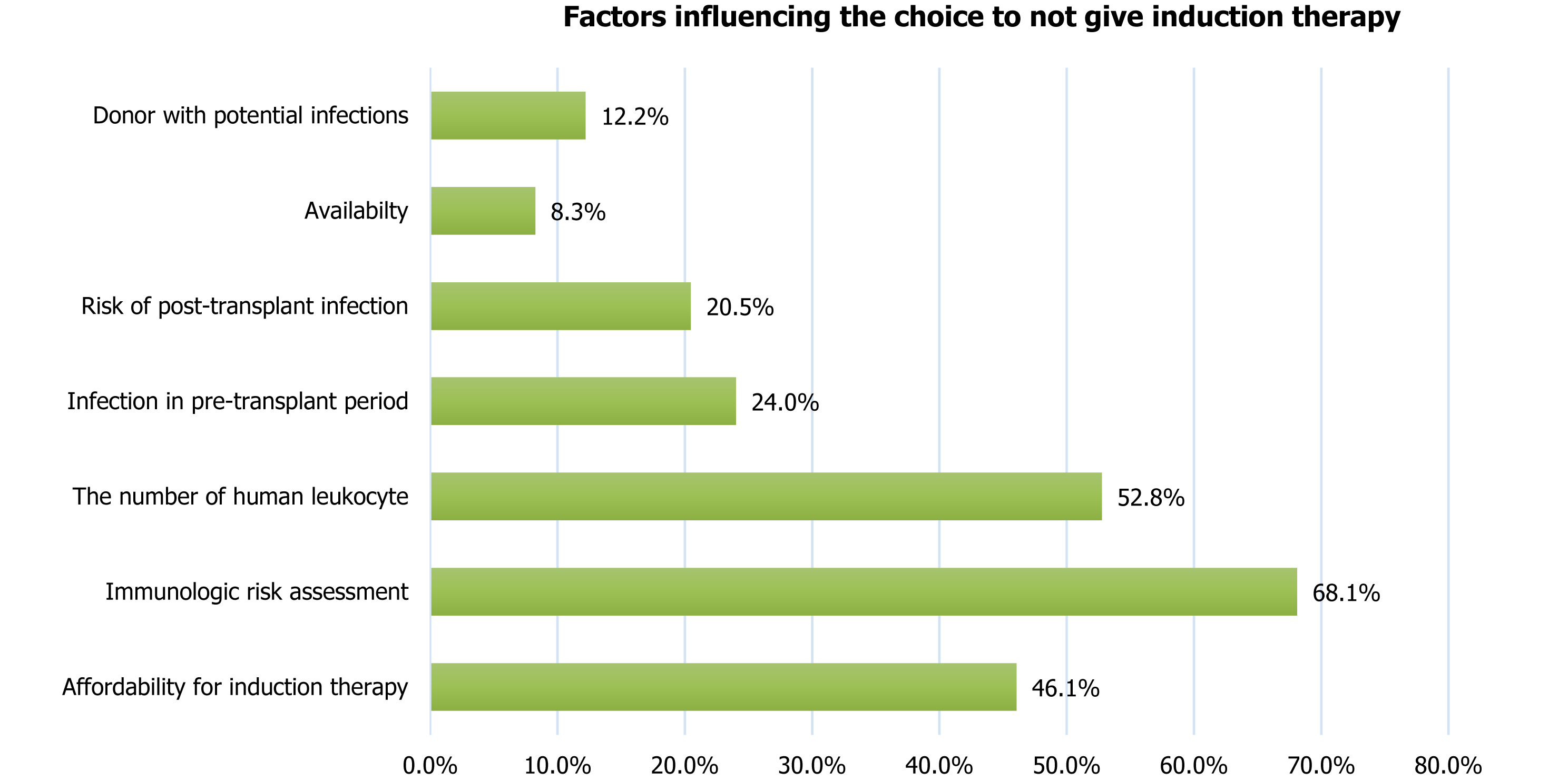

The survey showed that the choice of not giving an induction therapy was predominantly influenced by immunological risk assessment (68.1%), the number of human leucocyte antigen (HLA) mismatches (52.8%), and the affordability of induction therapy (46.1%). Other factors considered by the specialists before deciding not to give an induction therapy are shown in Figure 6. Similar determinants - including affordability, inequities in access, steroid-free regimens, and centre-level practice variation - have also been highlighted in previous studies[65-72].

Statement 15: ISOT suggests that the choice of induction therapy should be based on: Immunologic risk assessment (low/intermediate/high), number of HLA mismatches, type of donor (living/deceased), age of recipient, infection in pre-transplant period, risk of post-transplant infection and diabetes, affordability and availability for induction therapy, steroid free regimen or not, and pre-transplant leukopenia. The above statement was accepted as consensus with voting results: Strongly agree (39.4%), agree (45.5%), neutral (9.1%), disagree (3.0%), strongly disagree (3.0%).

Statement 16: ISOT suggests that the choice of not giving an induction therapy should be based on affordability and availability for induction therapy; immunologic risk assessment (low/intermediate/high); number of HLA mismatches; infection in pre-transplant period; risk of post-transplant infection and diabetes; and donor with potential infections. The above statement was accepted as consensus with voting results: Strongly agree (42.9%), agree (39.3%), neutral (3.6%), disagree (3.6%), strongly disagree (10.7%).

This consensus document has certain limitations. The recommendations are primarily based on reported practice patterns and expert opinion rather than outcome-based clinical evidence. Heavy reliance on survey responses may reduce the overall scientific rigor. Some strategies are extrapolated from adult data to elderly and pediatric recipients due to the lack of robust age-specific outcome studies. Comorbidity-driven variations, such as diabetes and infection risk, are not fully addressed because of limited evidence. Future research should focus on multicenter prospective outcome studies and longitudinal follow-up, with the development of age-, risk-, and comorbidity-specific induction protocols to validate and refine these recommendations.

KT is the most common organ transplant in India. A survey conducted by ISOT showed great heterogeneity in the choice of induction therapy in LDKTRs and DDKTRs of different immunological risk profiles, age, and comorbidities like diabetes or when they received kidneys from DDs with AKI. The survey showed that rATG was the most common induction used in DDKTRs, followed by IL-2RB. The 16 consensus statements cover the choice of induction during common KT clinical scenarios in India and the factors the treating specialist should consider before choosing an induction therapy. rATG was the choice of induction in most high immunological risk cases, and IL-2RB was the choice of induction in most low immunological risk cases.

| 1. | Ghosh S. Kidney transplants remain highest in India, followed by liver and heart: Govt data. Mint. 2023. [cited 15 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.livemint.com. |

| 2. | Kasiske BL, Zeier MG, Chapman JR, Craig JC, Ekberg H, Garvey CA, Green MD, Jha V, Josephson MA, Kiberd BA, Kreis HA, McDonald RA, Newmann JM, Obrador GT, Vincenti FG, Cheung M, Earley A, Raman G, Abariga S, Wagner M, Balk EM; Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the care of kidney transplant recipients: a summary. Kidney Int. 2010;77:299-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 442] [Cited by in RCA: 533] [Article Influence: 31.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wiseman AC. Induction Therapy in Renal Transplantation: Why? What Agent? What Dose? We May Never Know. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10:923-925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Pal DK, Roy PPS. Factors Influencing Delayed Graft Function in Deceased Renal Transplant: A Single Tertiary Care Center Experience. Indian J Transplant. 2023;17:209-214. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | George J. Perspective Chapter: Low Cost Immunosuppressive Strategies in Renal Transplantation. In: Tyagi RK, Sharma P, Sharma P. Immunosuppression and Immunomodulation. London: IntechOpen, 2023. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 6. | Gang S, Gulati S, Bhalla AK, Varma PP, Bansal R, Abraham A, Ray DS, John MM, Bansal SB, Sharma RK, Vishwanath S; ATLG Registry Investigators Group. One-Year Outcomes with Use of Anti-T-Lymphocyte Globulin in Patients Undergoing Kidney Transplantation: Results from a Prospective, Multicentric, Observational Study from India. Adv Ther. 2022;39:4533-4541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hardinger KL, Brennan DC, Klein CL. Selection of induction therapy in kidney transplantation. Transpl Int. 2013;26:662-672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Linstone HA, Turoff M. The Delphi Method: Techniques and Applications. United States: Addison-Wesley, 1975. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Singh N, Rossi AP, Savic M, Rubocki RJ, Parker MG, Vella JP. Tailored Rabbit Antithymocyte Globulin Induction Dosing for Kidney Transplantation. Transplant Direct. 2018;4:e343. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Dharnidharka VR, Naik AS, Axelrod DA, Schnitzler MA, Zhang Z, Bae S, Segev DL, Brennan DC, Alhamad T, Ouseph R, Lam NN, Nazzal M, Randall H, Kasiske BL, McAdams-Demarco M, Lentine KL. Center practice drives variation in choice of US kidney transplant induction therapy: a retrospective analysis of contemporary practice. Transpl Int. 2018;31:198-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sharma A. Induction Agent in Low Immunological Risk; the Indian Scenario. Urol Nephrol Open Access J. 2016;3. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 12. | Bavikar S, Ganjewar V, Oswal A, Bavikar P. ABO-Incompatible and Human Leukocyte Antigen-Incompatible Kidney Transplant in a Highly Sensitized Patient with Hepatitis-B. Indian J Transplant. 2023;17:245-248. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Stevens RB, Wrenshall LE, Miles CD, Farney AC, Jie T, Sandoz JP, Rigley TH, Osama Gaber A. A Double-Blind, Double-Dummy, Flexible-Design Randomized Multicenter Trial: Early Safety of Single- Versus Divided-Dose Rabbit Anti-Thymocyte Globulin Induction in Renal Transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:1858-1867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Stevens RB, Mercer DF, Grant WJ, Freifeld AG, Lane JT, Groggel GC, Rigley TH, Nielsen KJ, Henning ME, Skorupa JY, Skorupa AJ, Christensen KA, Sandoz JP, Kellogg AM, Langnas AN, Wrenshall LE. Randomized trial of single-dose versus divided-dose rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin induction in renal transplantation: an interim report. Transplantation. 2008;85:1391-1399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Stevens RB, Foster KW, Miles CD, Lane JT, Kalil AC, Florescu DF, Sandoz JP, Rigley TH, Nielsen KJ, Skorupa JY, Kellogg AM, Malik T, Wrenshall LE. A randomized 2×2 factorial trial, part 1: single-dose rabbit antithymocyte globulin induction may improve renal transplantation outcomes. Transplantation. 2015;99:197-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Genzyme Corporation. Highlights of prescribing information: Thymoglobulin (anti-thymocyte globulin [rabbit]) for intravenous use. Cambridge: Genzyme, 2017. |

| 17. | Frutos MÁ, Crespo M, Valentín MO, Alonso-Melgar Á, Alonso J, Fernández C, García-Erauzkin G, González E, González-Rinne AM, Guirado L, Gutiérrez-Dalmau A, Huguet J, Moral JLLD, Musquera M, Paredes D, Redondo D, Revuelta I, Hofstadt CJV, Alcaraz A, Alonso-Hernández Á, Alonso M, Bernabeu P, Bernal G, Breda A, Cabello M, Caro-Oleas JL, Cid J, Diekmann F, Espinosa L, Facundo C, García M, Gil-Vernet S, Lozano M, Mahillo B, Martínez MJ, Miranda B, Oppenheimer F, Palou E, Pérez-Saez MJ, Peri L, Rodríguez O, Santiago C, Tabernero G, Hernández D, Domínguez-Gil B, Pascual J. Recommendations for living donor kidney transplantation. Nefrologia (Engl Ed). 2022;42 Suppl 2:5-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Shim YE, Ko Y, Lee JP, Jeon JS, Jun H, Yang J, Kim MS, Lim SJ, Kwon HE, Jung JH, Kwon H, Kim YH, Lee J, Shin S; Korean Organ Transplantation Registry (KOTRY) study group. Evaluating anti-thymocyte globulin induction doses for better allograft and patient survival in Asian kidney transplant recipients. Sci Rep. 2023;13:12560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Park BH, Kim YN, Shin HS, Jung Y, Rim H. Current use of antithymoglobulin as induction regimen in kidney transplantation: A review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024;103:e37242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Mehra A, Bansal N, Koushal V. A study of sociodemographic profile and level of awareness of the decision makers for organ donation of deceased organ donors in a Tertiary Care Hospital. Indian J Transplant. 2019;13:82. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Shi X, Lv J, Han W, Zhong X, Xie X, Su B, Ding J. What is the impact of human leukocyte antigen mismatching on graft survival and mortality in renal transplantation? A meta-analysis of 23 cohort studies involving 486,608 recipients. BMC Nephrol. 2018;19:116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Sureshkumar KK, Chopra B. Induction Type and Outcomes in HLA-DR Mismatch Kidney Transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2019;51:1796-1800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Miller JT, Collins CD, Stuckey LJ, Luan FL, Englesbe MJ, Magee JC, Park JM. Clinical and economic outcomes of rabbit antithymocyte globulin induction in adults who received kidney transplants from living unrelated donors and received cyclosporine-based immunosuppression. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29:1166-1174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hardinger KL, Schnitzler MA, Koch MJ, Labile E, Stirnemann PM, Miller B, Enkvetchakul D, Brennan DC. Thymoglobulin induction is safe and effective in live-donor renal transplantation: a single center experience. Transplantation. 2006;81:1285-1289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Schenker P, Ozturk A, Vonend O, Krüger B, Jazra M, Wunsch A, Krämer B, Viebahn R. Single-dose thymoglobulin induction in living-donor renal transplantation. Ann Transplant. 2011;16:50-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Alloway RR, Woodle ES, Abramowicz D, Segev DL, Castan R, Ilsley JN, Jeschke K, Somerville KT, Brennan DC. Rabbit anti-thymocyte globulin for the prevention of acute rejection in kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2019;19:2252-2261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Brennan DC, Daller JA, Lake KD, Cibrik D, Del Castillo D; Thymoglobulin Induction Study Group. Rabbit antithymocyte globulin versus basiliximab in renal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1967-1977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 573] [Cited by in RCA: 561] [Article Influence: 28.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Lentine KL, Schnitzler MA, Xiao H, Brennan DC. Long-term safety and efficacy of antithymocyte globulin induction: use of integrated national registry data to achieve ten-year follow-up of 10-10 Study participants. Trials. 2015;16:365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Boucquemont J, Foucher Y, Masset C, Legendre C, Scemla A, Buron F, Morelon E, Garrigue V, Pernin V, Albano L, Sicard A, Girerd S, Ladrière M, Giral M, Dantal J; DIVAT consortium. Induction therapy in kidney transplant recipients: Description of the practices according to the calendar period from the French multicentric DIVAT cohort. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0240929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Jeong ES, Lee KW, Kim SJ, Yoo HJ, Kim KA, Park JB. Comparison of clinical outcomes of deceased donor kidney transplantations, with a focus on three induction therapies. Korean J Transplant. 2019;33:118-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Hellemans R, Bosmans JL, Abramowicz D. Induction Therapy for Kidney Transplant Recipients: Do We Still Need Anti-IL2 Receptor Monoclonal Antibodies? Am J Transplant. 2017;17:22-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Qiu J, Li J, Chen G, Huang G, Fu Q, Wang C, Chen L. Induction therapy with thymoglobulin or interleukin-2 receptor antagonist for Chinese recipients of living donor renal transplantation: a retrospective study. BMC Nephrol. 2019;20:101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Webster AC, Ruster LP, McGee R, Matheson SL, Higgins GY, Willis NS, Chapman JR, Craig JC. Interleukin 2 receptor antagonists for kidney transplant recipients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;2010:CD003897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Jha PK, Bansal SB, Sharma R, Sethi SK, Bansal D, Nandwani A, Kher A, Yadav DK, Gadde A, Mahapatra AK, Rana AS, Sodhi P, Jain M, Kher V. Role of Induction in a Haplomatch, Related, Low-Risk, Living-Donor Kidney Transplantation with Triple Drug Immunosuppression: A Single-Center Study. Indian J Nephrol. 2024;34:246-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Abou-Jaoudé M, Akiki D, Moussawi A, Abou-Jaoudé W. The impact of induction therapy in low-immunological risk kidney transplant recipients regardless of HLA matching. Transpl Immunol. 2023;76:101773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Gosain V, Kar C, Rout S. SAT-338 the dilemma of induction immunosuppression in low immunological risk kidney transplant recipients- a prospective randomised study from eastern india comparing basiliximab versus no induction immunosuppression. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5:S141-S142. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Kaushal R, Srivastava A, Singh K. A Case Report of ABO-Incompatible Kidney Transplant in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Positive Patient Coinfected with Both Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C Viruses. Indian J Transplant. 2022;16:455-457. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Bansal S, Pathania D, Sethi S, Jha P, Nandwani A, Jain M, Mahapatra A, Kher V. Basiliximab induction in living donor kidney transplant with tacrolimus-based triple immunosuppression. Indian J Transplant. 2019;13:104. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Basu G, Radhakrishnan R, Mohapatra A, Alexander S, Valson A, Jacob S, David V, Varughese S, Veerasami T. Utility of induction agents in living donor kidney transplantation. Indian J Transplant. 2019;13:202. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Tydén G, Kumlien G, Fehrman I. Successful ABO-incompatible kidney transplantations without splenectomy using antigen-specific immunoadsorption and rituximab. Transplantation. 2003;76:730-731. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 214] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Lo P, Sharma A, Craig JC, Wyburn K, Lim W, Chapman JR, Palmer SC, Strippoli GF, Wong G. Preconditioning Therapy in ABO-Incompatible Living Kidney Transplantation: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Transplantation. 2016;100:933-942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Kute V, Ray DS, Dalal S, Hegde U, Godara S, Pathak V, Bahadur MM, Khullar D, Guleria S, Vishwanath S, Singhare A, Yadav D, Bansal SB, Chauhan S, Meshram HS. A Multicenter Cohort Study From India of ABO-Incompatible Kidney Transplantation in Post-COVID-19 Patients. Transplant Proc. 2022;54:2652-2657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Jha V, Bhalla A, Anil Kumar B, Chauhan M, Das P, Gandhi B, Hegde U, Jeloka T, Mali M, Jha P, Kher A, Mukkavilli K, Ramachandran R. ABO-incompatible kidney transplantation: Indian working group recommendations. Indian J Transplant. 2019;13:252. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Shirakawa H, Ishida H, Shimizu T, Omoto K, Iida S, Toki D, Tanabe K. The low dose of rituximab in ABO-incompatible kidney transplantation without a splenectomy: a single-center experience. Clin Transplant. 2011;25:878-884. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Lee HR, Kim K, Lee SW, Song JH, Lee JH, Hwang SD. Effect of rituximab dose on induction therapy in ABO-incompatible living kidney transplantation: A network meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e24853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Jha PK, Bansal SB, Rana A, Nandwani A, Kher A, Sethi S, Jain M, Bansal D, Yadav DK, Gadde A, Mahapatra AK, Sodhi P, Ahlawat R, Kher V. ABO-Incompatible Kidney Transplantation in India: A Single-Center Experience of First Hundred Cases. Indian J Nephrol. 2022;32:42-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Working Party of The British Transplantation Society. Guidelines for antibody incompatible transplantation. 3rd ed. London: British Transplantation Society, 2015. |

| 48. | Kim KD, Lee KW, Park JB, Sim WS, Lim M, Jeong ES, Kwon J, Yang J. Necessity of induction agent modification for old age kidney transplant recipients. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2025;44:349-360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Gill J, Sampaio M, Gill JS, Dong J, Kuo HT, Danovitch GM, Bunnapradist S. Induction immunosuppressive therapy in the elderly kidney transplant recipient in the United States. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:1168-1178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Ahn JB, Bae S, Chu NM, Wang L, Kim J, Schnitzler M, Hess GP, Lentine KL, Segev DL, McAdams-DeMarco MA. The Risk of Postkidney Transplant Outcomes by Induction Choice Differs by Recipient Age. Transplant Direct. 2021;7:e715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Catibog CJM, Marbella MAG. Outcome of Renal Transplantation in Children Given Rabbit Anti-Thymocyte Globulin (rATG) as Induction Therapy. Transplant Proc. 2022;54:307-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Custodio LFP, Martins SBS, Viana LA, Cristelli MP, Requião-Moura L, Chow CYZ, Camargo SFDN, Nakamura MR, Foresto RD, Tedesco-Silva H, Medina-Pestana J. Efficacy and safety of single-dose anti-thymocyte globulin versus basiliximab induction therapy in pediatric kidney transplant recipients: A retrospective comparative cohort study. Pediatr Transplant. 2024;28:e14713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Foster BJ, Dahhou M, Zhang X, Platt RW, Samuel SM, Hanley JA. Association between age and graft failure rates in young kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2011;92:1237-1243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 174] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Rangel EB, de Sá JR, Melaragno CS, Gonzalez AM, Linhares MM, Salzedas A, Medina-Pestana JO. Kidney transplant in diabetic patients: modalities, indications and results. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2009;1:2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Choudhury PS, Mukhopadhyay P, Roychowdhary A, Chowdhury S, Ghosh S. Prevalence and Predictors of "New-onset Diabetes after Transplantation" (NODAT) in Renal Transplant Recipients: An Observational Study. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2019;23:273-277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Swarnalatha G, Karthik KR, Bharathi N, Raghavendra S, Siva Parvathi K, Deepti A, Gangadhar T. New onset diabetes after renal transplantation: An experience from a developing country. India Int Arch Integr Med. 2017;4:74-82. |

| 57. | Dwivedi R, Shashikiran KB, Manuel S, Ansari FA, Madipalli RT, Golla A, Raju SB. Induction with rATG versus No-induction in Deceased Donor Renal Transplantation - A Retrospective Observational Study. Indian J Nephrol. 2022;32:423-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Hardinger KL, Brennan DC, Schnitzler MA. Rabbit antithymocyte globulin is more beneficial in standard kidney than in extended donor recipients. Transplantation. 2009;87:1372-1376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Hong SY, Kim YS, Jin K, Han S, Yang CW, Chung BH, Park WY. The comparative efficacy and safety of basiliximab and antithymocyte globulin in deceased donor kidney transplantation: a multicenter cohort study. Kidney Res Clin Pract. 2023;42:138-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Kumar A, Agarwal C, Hooda AK, Ojha A, Dhillon M, Hari Kumar KV. Profile of infections in renal transplant recipients from India. J Family Med Prim Care. 2016;5:611-614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Baker RJ, Mark PB, Patel RK, Stevens KK, Palmer N. Renal association clinical practice guideline in post-operative care in the kidney transplant recipient. BMC Nephrol. 2017;18:174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Bhagat C, Mathur RP, Sharma N. Spectrum of Infections in Kidney Transplant Recipients: A Single Centre Retrospective Cohort Study. Indian J Transplant. 2023;17:310-315. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 63. | Kumar A, dhanapriya J, dineshkumar T, sakthirajan R, balasubramaniayan T, gopalakrishnan N. SAT-351 post-renal transplant infections: a two decade experience. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5:S147. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Bansal SB, Ramasubramanian V, Prasad N, Saraf N, Soman R, Makharia G, Varughese S, Sahay M, Deswal V, Jeloka T, Gang S, Sharma A, Rupali P, Shah DS, Jha V, Kotton CN. South Asian Transplant Infectious Disease Guidelines for Solid Organ Transplant Candidates, Recipients, and Donors. Transplantation. 2023;107:1910-1934. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Haller MC, Royuela A, Nagler EV, Pascual J, Webster AC. Steroid avoidance or withdrawal for kidney transplant recipients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2016:CD005632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Ekberg J, Baid-Agrawal S, Jespersen B, Källén R, Rafael E, Skov K, Lindnér P. A Randomized Controlled Trial on Safety of Steroid Avoidance in Immunologically Low-Risk Kidney Transplant Recipients. Kidney Int Rep. 2022;7:259-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Henningsen M, Jaenigen B, Zschiedrich S, Pisarski P, Walz G, Schneider J. Risk Factors and Management of Leukopenia After Kidney Transplantation: A Single-Center Experience. Transplant Proc. 2021;53:1589-1598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Ali H, Mohammed M, Fülöp T, Malik S. Outcomes of thymoglobulin versus basiliximab induction therapies in living donor kidney transplant recipients with mild to moderate immunological risk - a retrospective analysis of UNOS database. Ann Med. 2023;55:2215536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Trivedi N, Sodani PR. A Study on the Economic Evaluation of End-stage Renal Disease Treatment: Kidney Transplantation Versus Haemodialysis. J Health Manag. 2024;26:284-292. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 70. | Banode RK, Kimmatkar PD, Bawankule CP, Adamane VP. Kidney transplant and its outcomes. J Curr Res Sci Med. 2021;7:55-61. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Elrggal ME, Gokcay Bek S, Shendi AM, Tannor EK, Nlandu YM, Gaipov A. Disparities in Access to Kidney Transplantation in Developing Countries. Transplantation. 2021;105:2325-2329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Sonnenberg EM, Cohen JB, Hsu JY, Potluri VS, Levine MH, Abt PL, Reese PP. Association of Kidney Transplant Center Volume With 3-Year Clinical Outcomes. Am J Kidney Dis. 2019;74:441-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/