Published online Mar 18, 2026. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v16.i1.114162

Revised: October 28, 2025

Accepted: December 18, 2025

Published online: March 18, 2026

Processing time: 121 Days and 21.6 Hours

Early renal artery thrombosis after kidney transplantation is rare but often leads to graft loss. Prompt diagnosis and intervention are essential, particularly in patients with inherited thrombophilias such as factor V Leiden (FVL) mutation.

A kidney transplant recipient with FVL mutation developed an acute transplant renal artery thrombosis. The immediate post-operative Doppler ultrasonography revealed thrombosis of the main and inferior polar renal arteries. Emergent thrombectomy and separate arterial re-anastomoses were performed after cold perfusion with heparinized saline and vasodilator solution. Reperfusion was successful with immediate urine output and gradual improvement in renal function. The patient was discharged on direct oral anticoagulation therapy.

Early detection and surgical intervention can preserve graft function in post-transplant renal artery thrombosis even in patients at high risk.

Core Tip: Vascular thrombosis is an uncommon but serious complication in renal transplantation. Vigilant postoperative monitoring is essential for early detection. We described the successful salvage of a renal allograft with arterial thrombosis in a patient with factor V Leiden mutation, using a technically challenging donor kidney with dual arteries.

- Citation: Lekehal B, Ait Youssef N, Lekehal M, Jdar A, El Hassani AEA, Belyazid I, Bakkali T, Bounssir A. Acute graft thrombosis in a patient with factor V Leiden mutation: A case report and review of literature. World J Transplant 2026; 16(1): 114162

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3230/full/v16/i1/114162.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v16.i1.114162

Vascular complications in renal transplantation are relatively frequent from either living related or cadaveric donors, occurring in about 3%-15% of cases, and can often result in allograft loss[1,2]. The most common complications include transplant renal artery stenosis, arterial or venous thrombosis, biopsy-related vascular injuries, pseudo-aneurysm formation, and hematomas[1,2]. Among these transplant renal artery thrombosis is particularly devastating. It typically occurs early, presents with severe clinical symptoms, and is a major cause of graft loss[1]. We report our surgical manage

A 48-year-old male with chronic renal disease secondary to immunoglobulin A (IgA) nephropathy presented for a preemptive living-donor kidney transplantation.

The patient had experienced progressive renal dysfunction over the prior several years. He was evaluated and deemed an appropriate candidate for living-donor renal transplantation. The donor, a 55-year-old male, was a living biological relative, who underwent left-sided donor nephrectomy.

The patient had a known history of chronic kidney disease leading to chronic renal insufficiency along with a documented coagulopathy due to FVL mutation. His medical history also included symptomatic gout, nonspecific acute thyroiditis complicated by hypothyroidism following radioactive iodine therapy, and recurrent venous thrombotic events, as follows. In 2001, the patient developed right popliteal vein thrombosis secondary to nephrotic syndrome (managed with warfarin, to resolution). In 2002, he presented with right superficial thrombophlebitis. In 2003, he experienced recurrent right superficial thrombophlebitis which was associated with a history of undocumented nephrotic syndrome; after this third venous thrombotic episode the patient was maintained on warfarin. There was no history of prior abdominal surgery.

The patient had no known familial history of hereditary renal diseases. The donor was a healthy biological relative with no history of chronic illness; notably, the donor had a body mass index (BMI) of 27.2 kg/m2, consistent with overweight status.

Preoperative physical examination revealed a hemodynamically stable patient for transplant receipt, presenting signs consistent with chronic renal disease and with a BMI of 24 kg/m2. There was no evidence of edema, ascites, nor infection. Cardiopulmonary and abdominal examination findings were within normal limits.

The patient’s hemoglobin was mildly decreased (consistent with anemia of chronic disease; 10 g/dL, normal range: 14-18 g/dL). His serum creatinine was elevated (11.0 mg/dL, normal range: 0.7-1.3 mg/dL). The coagulation profile revealed normal fibrinogen, antithrombin III, protein S, and protein C. Tests for lupus anticoagulants and anti-phospholipid antibodies were negative. The crossmatch test was negative, the human leukocyte antigen compatibility test was acceptable, and the panel-reactive antibody test was low.

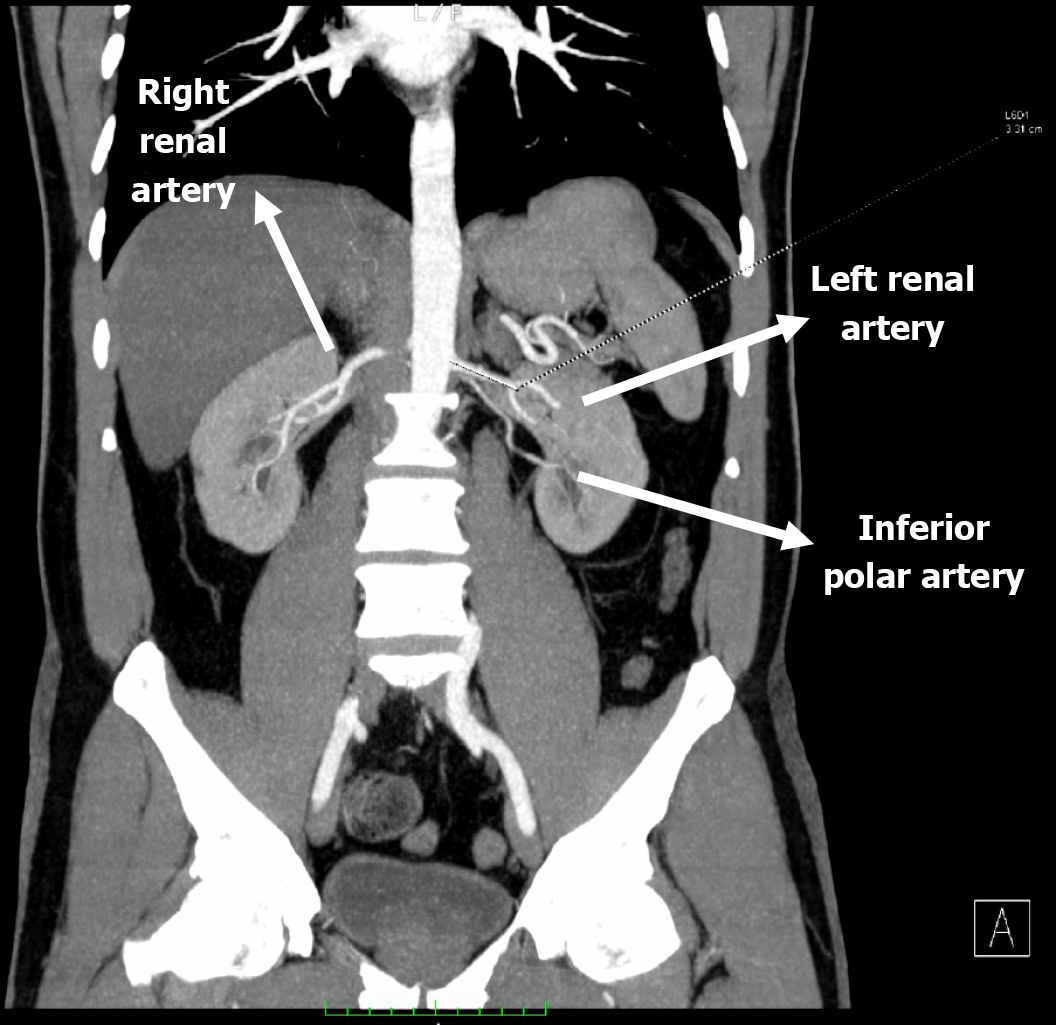

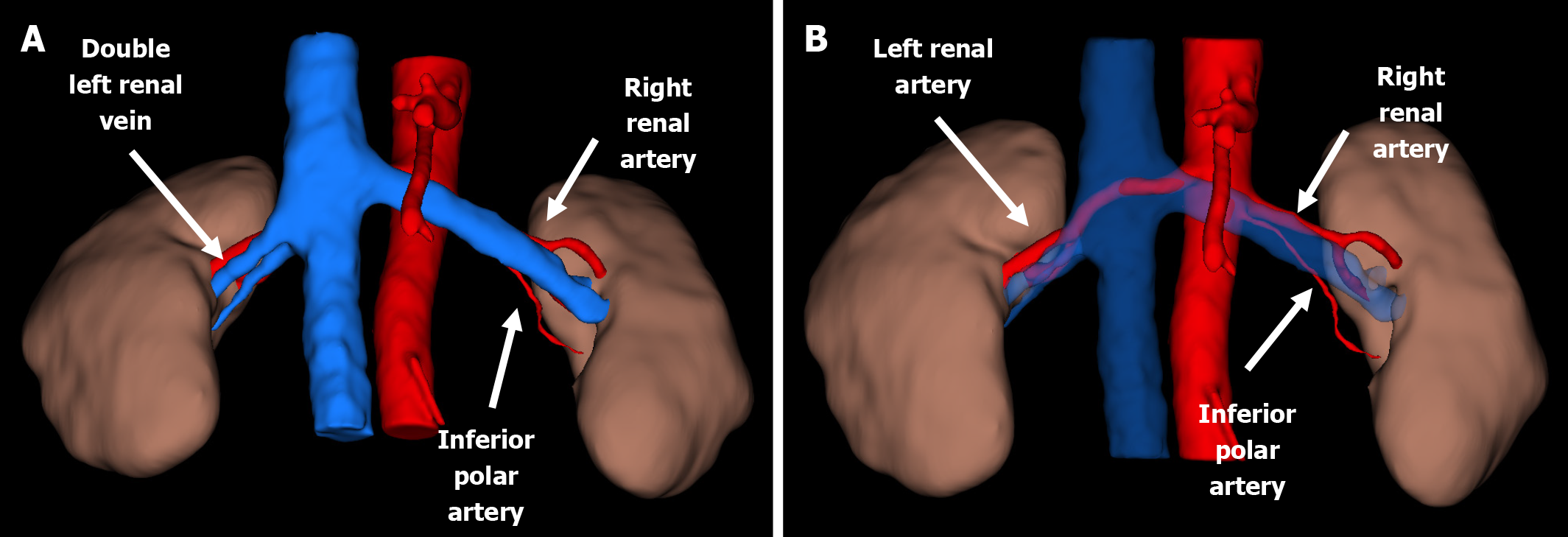

Preoperative recipient imaging showed normal anatomy of the iliac vessels and no significant vascular calcification. Donor computed tomography (CT) angiography showed the left kidney with two renal arteries and the right kidney with a double renal vein (Figures 1 and 2). We chose the left kidney because it had the least renal function, according to evaluation by scintigraphy, and the most appropriate anatomy.

Analysis of genomic DNA with polymerase chain reaction using specific primers indicated the presence of both guanine and adenine at nucleotide 1691, consistent with heterozygous FVL.

A multidisciplinary transplant team including nephrologists, transplant surgeons, and anesthesiologists had evaluated and optimized the patient preoperatively.

Chronic kidney disease due to IgA nephropathy and intraoperative vascular challenge due to the presence of an accessory renal artery requiring an additional anastomosis.

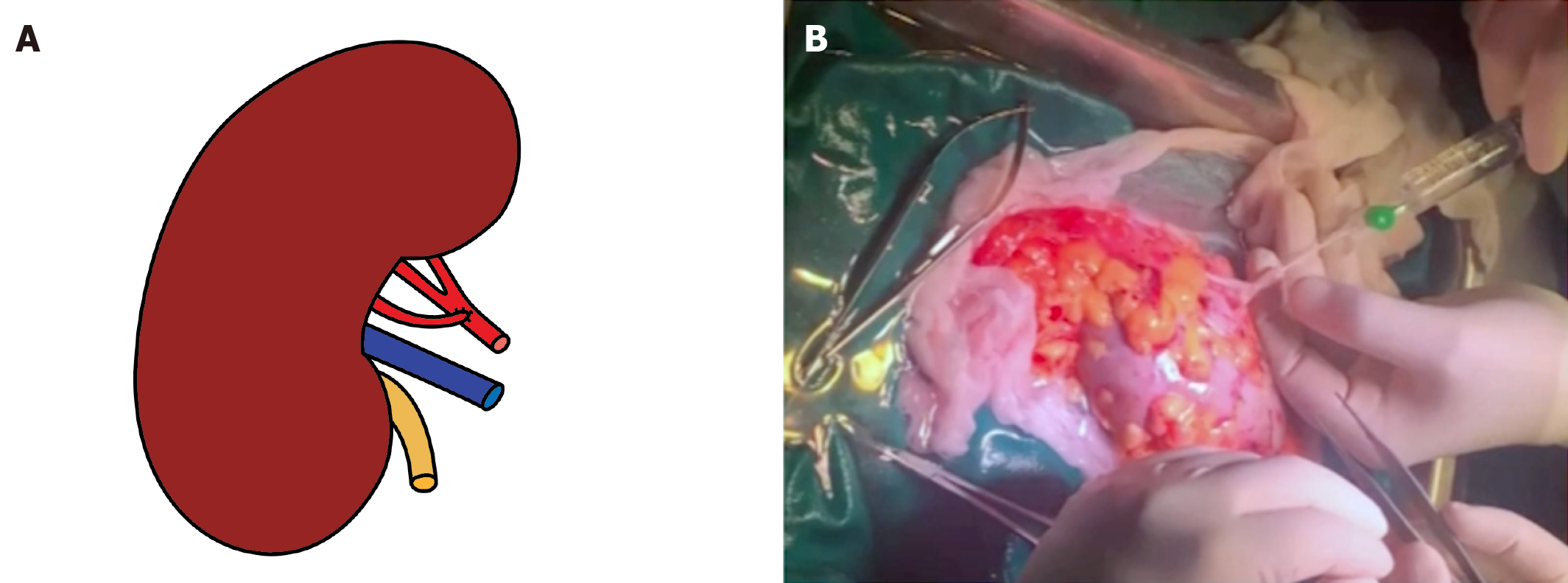

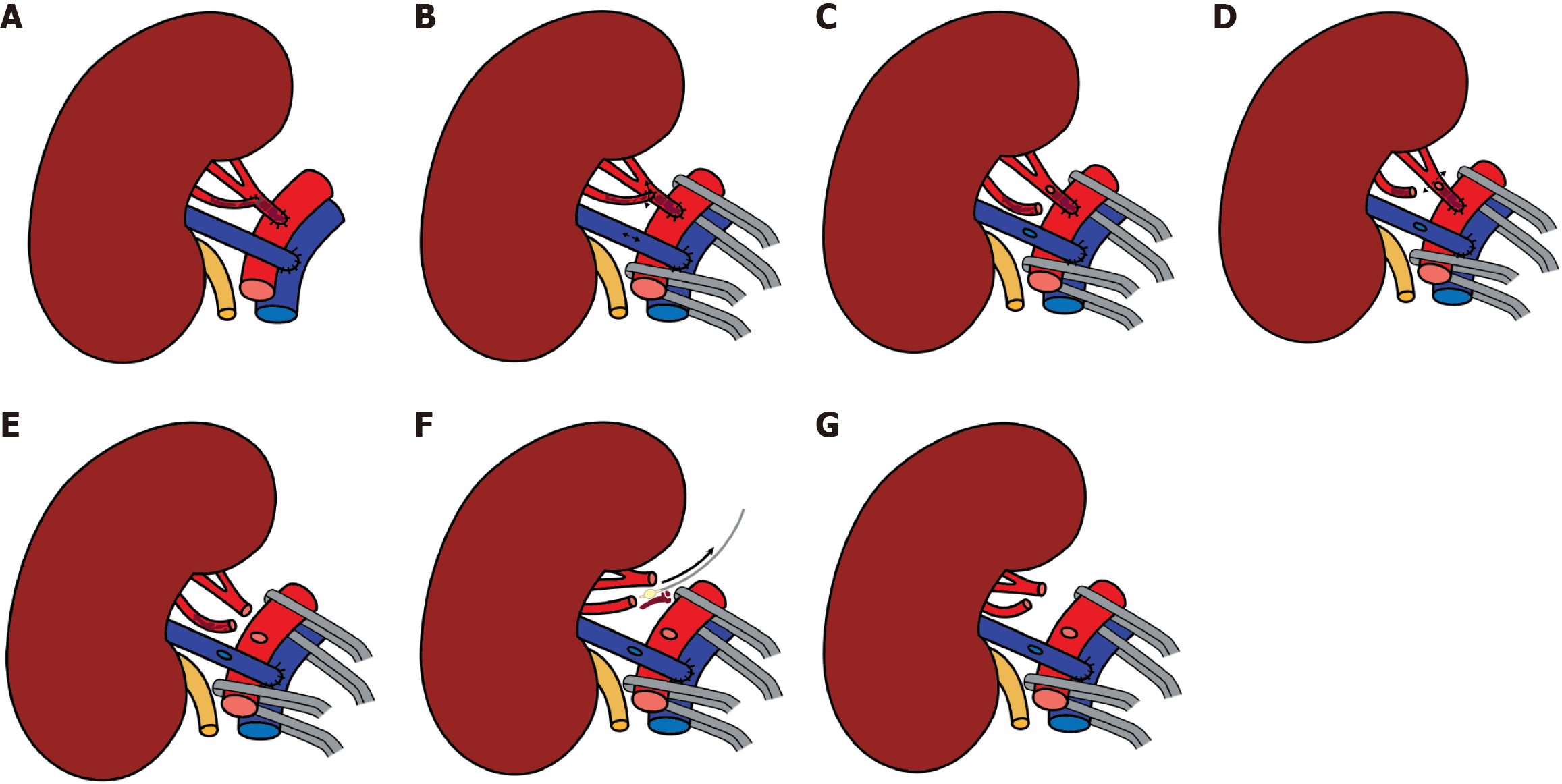

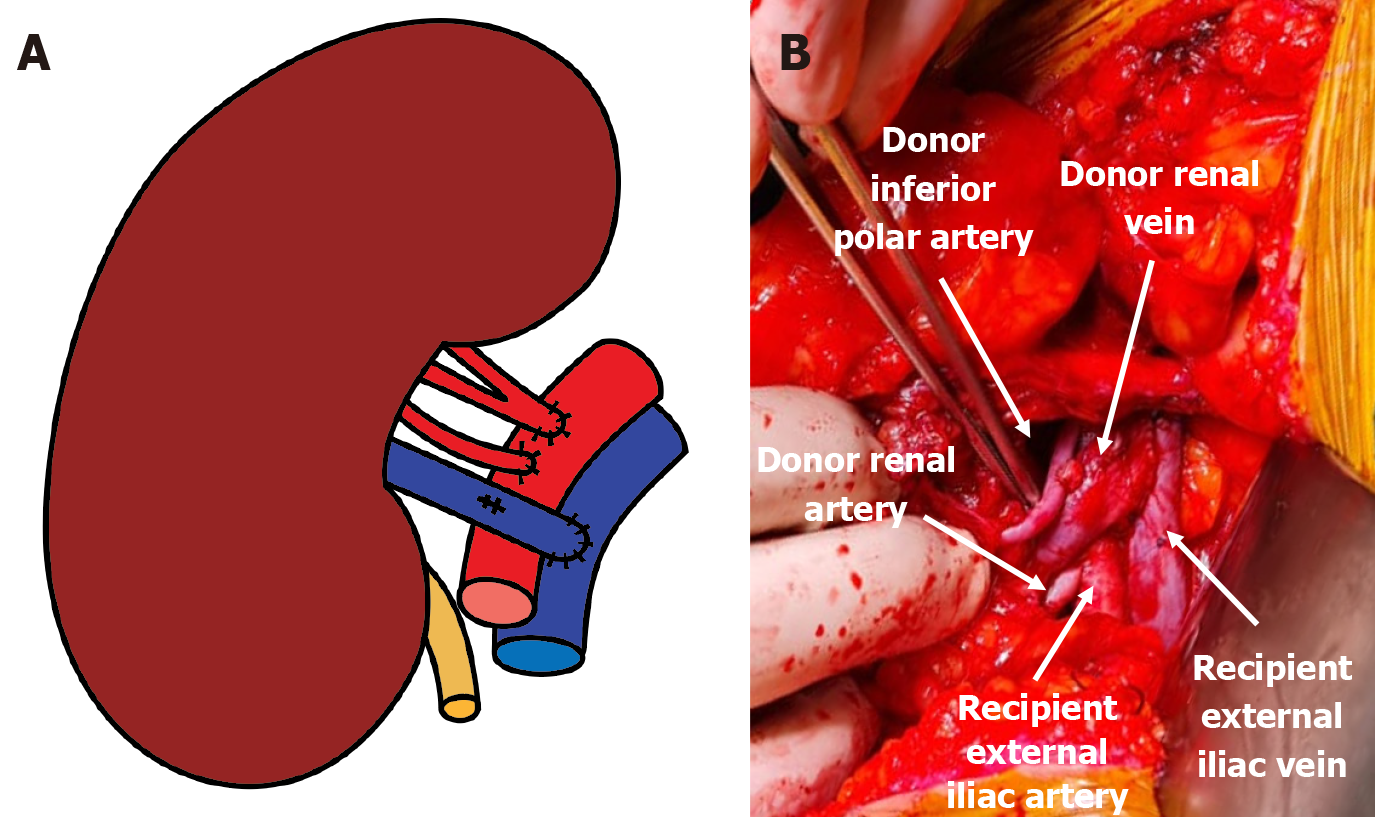

A left donor kidney was retrieved via hand-assisted laparoscopic nephrectomy. Transplantation was performed in the recipient’s right iliac fossa using a pararectal approach. Venous anastomosis was created end-to-side to the fully mobilized right external iliac vein. The main renal artery was anastomosed end-to-side to the external iliac artery, and the inferior polar artery was previously transposed into the main renal artery in the back-table (Figures 3 and 4). Following declamping, the graft reperfused immediately with prompt urine output. No intraoperative complications were noted.

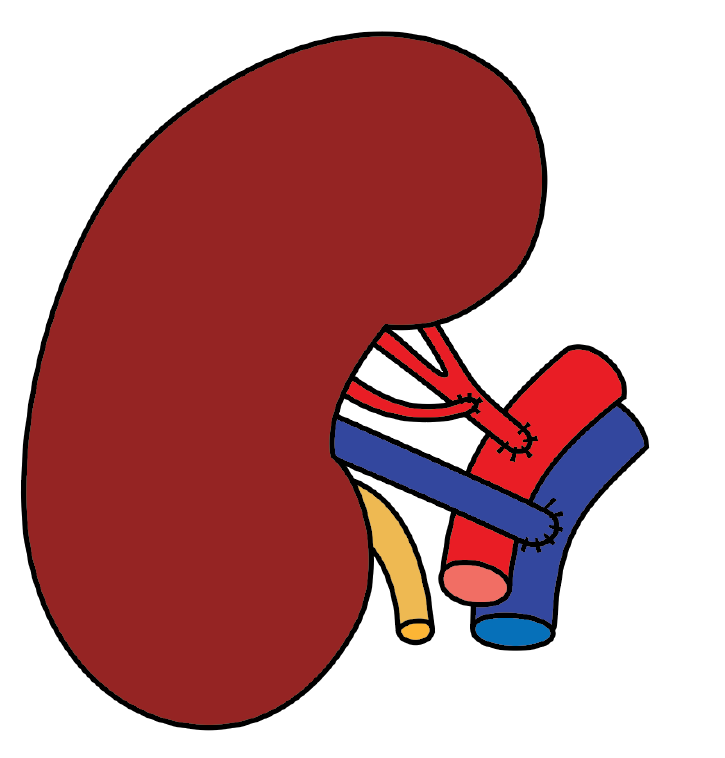

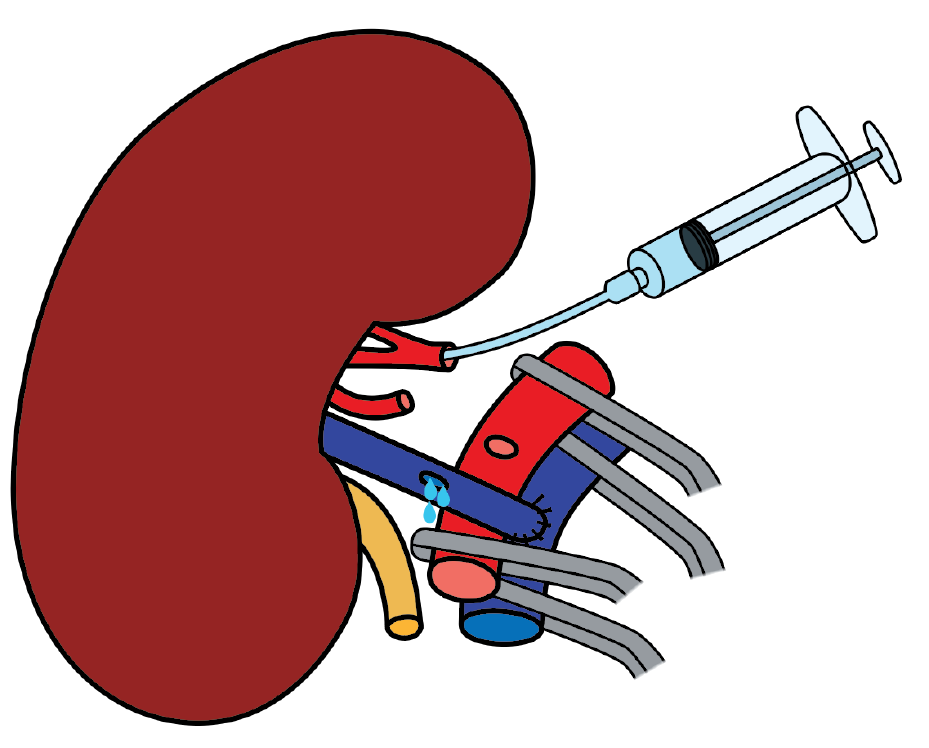

The immediate postoperative Doppler ultrasonography showed absent flow in both the main and accessory renal arteries, consistent with allograft renal artery thrombosis. An emergent surgical re-exploration was performed through the same incision. The graft appeared shrunken but viable. Both arteries were occluded with thrombus, and the vein was empty. The arterial anastomosis was dismantled under cold ischemia, and the thrombus was removed (Figure 5). While the graft remained in place, it was flushed with cold heparinized saline and vasodilator solution until pale and cold through venotomy (Figure 6). Separate end-to-side re-anastomoses of the main and inferior polar arteries were performed (Figure 7). Upon reperfusion the graft regained normal color, turgor, and perfusion.

Intraoperatively, there were no episodes of hypotension, no requirement for inotropic support, nor any significant blood loss. The total ischemia time was 105 minutes, comprising 60 minutes of warm ischemia and 45 minutes of cold ischemia.

Reperfusion was achieved with immediate restoration of urine output. Postoperative Doppler ultrasonography confirmed patent arterial and venous flows without evidence of thrombosis. The standard immunosuppressive protocol was resumed, and the unfractionated heparin anticoagulant therapy that had been initiated during the preoperative phase was continued in the postoperative phase, with activated cephalin time monitoring.

The postoperative course was uneventful aside from postoperative thrombocytopenia on day 5, raising suspicion of type II heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, prompting a switch to an alternative anticoagulant. The patient was later discharged on long-term direct oral anticoagulation therapy (7.5 mg/day Eliquis; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company). Immunosuppression included thymoglobulin induction that transitioned to tacrolimus on postoperative day 3 along with prednisone, mycophenolate mofetil, sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim, and valganciclovir.

Imaging follow-up 2 years post-transplantation showed no signs of vascular compromise nor thrombosis. The patient experienced no complications and maintained stable renal function throughout the follow-up period.

Renal allograft thrombosis involving either the arterial or venous vasculature is a well-recognized complication of kidney transplantation. It most frequently occurs in the early postoperative period although late onset is also possible. Unfortunately, the prognosis remains poor regardless of the time of onset[3]. Most renal allograft thrombosis occurs early in the postoperative period, peaking within the first 48 h. However, thrombus formation can also be delayed beyond the first week[4].

Transplant renal artery thrombosis manifesting 2 or more weeks post-transplantation is classified as late renal artery thrombosis. This rare complication typically results from severe renal artery stenosis with consequent secondary thrombosis, or iatrogenic intimal injury during percutaneous endovascular procedures, or occurs in the context of graft rejection[5-7]. Delayed diagnosis and management of these complications can lead to significant morbidity with high risks of graft loss and mortality[8]. The incidence of arterial thrombosis ranges from 0.2%-7.5% and venous thrombosis from 0.1%-8.2% with the highest rates observed in pediatric and infant recipients and the lowest in series involving exclusively living donors. Variations in incidence reflect differences in recipient-donor composition, particularly the proportion of deceased donors[9].

Several factors may contribute to the pathogenesis of graft thrombosis, including variables related to the recipient, donor, transplantation, and surgery. Recipient-related factors such as advanced and very young age, history of diabetes mellitus, history of atherosclerosis and heart disease, perioperative or postoperative hemodynamic instability, cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection, toxicity of immunosuppressive agents, primary renal disease, mode of dialysis prior to trans

The underlying etiology of end-stage renal disease in the recipient also influences transplantation outcomes. Notably, diabetic nephropathy[10-12] is associated with an elevated risk of thrombosis, likely attributable to diabetic angiopathy. Additionally, atherosclerotic involvement of the vascular structures in either the recipient or the donor further augments this thrombotic risk[13,14].

Intraoperative and postoperative hemodynamic instability constitutes a significant risk factor for the development of graft thrombosis. Many studies identified it as an independent determinant of thrombotic events[10-15]. Pediatric data suggest that this factor may be even more critical in children, with younger patients being particularly susceptible to non-technical thrombosis due to relatively low cardiac output, especially when receiving a disproportionately large graft. This hemodynamic mismatch can result in suboptimal renal perfusion[16]. Accordingly, the implementation of aggressive fluid resuscitation and rigorous cardiovascular monitoring is imperative in such cases. CMV seropositive and seroconverted renal transplant recipients have been reported to exhibit a higher risk of venous thrombosis compared with recipients who are CMV-negative[17].

The incidence of acute transplant renal artery thrombosis has been reported to be higher among recipients treated with cyclosporine, ranging from 1.8%-7.0%, compared with 0%-1.0% in those receiving azathioprine and prednisone[18,19]. While cyclosporine exerts multiple biological effects, its most likely prothrombotic mechanism is the reduction of prostacyclin production by endothelial cells, thereby promoting thrombus formation[20]. Nonetheless, the association between cyclosporine use and renal allograft thrombosis remains controversial. Early clinical and experimental studies reported an increased incidence of renal vascular thrombosis and microvascular injury under cyclosporine-based immunosuppression, potentially related to vasoconstriction and endothelial dysfunction[18,21-24]. Subsequent investigations further described cyclosporine-induced chronic vascular and microvascular damage, which may predispose to thrombotic complications, particularly in the presence of unfavorable donor vascular anatomy[25-30]. However, other studies did not demonstrate a significant increase in renal allograft vascular thrombosis attributable to cyclosporine therapy when compared with alternative immunosuppressive regimens[31-35].

Renal artery graft thrombosis may also be precipitated by the administration of the monoclonal antibody OKT3, which has been shown to induce procoagulant activity[36,37]. The risk is further elevated in patients pretreated with high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone as this may activate the tissue factor/factor VII pathway[38]. Consequently, the recommended premedication dose of methylprednisolone should not exceed 8 mg/kg[39].

Pre-transplant peritoneal dialysis has been reported to be associated with a higher incidence of transplant renal artery thrombosis. Epidemiological data indicate a higher thrombotic risk among recipients who underwent re-transplant and in patients who underwent peritoneal dialysis prior to transplantation compared with those maintained on hemodialysis[10,14,40-43].

The pathophysiological basis may involve an acquired thrombophilic state, potentially resulting from selective protein losses into the peritoneal fluid, analogous to nephrotic syndrome. Additionally, patient selection factors may contribute; individuals switched from hemodialysis to peritoneal dialysis due to vascular access complications (often suggestive of underlying atherosclerosis) have been shown to have a greater thrombotic risk with the switch itself posing more risk than peritoneal dialysis alone[11].

Hypercoagulative states, also referred to as thrombophilias, comprise hereditary or acquired conditions that pre

The presence of anti-phospholipid antibodies has been recognized as an important risk factor for early allograft failure[45]. While anti-phospholipid antibodies are found in approximately 10% of patients awaiting renal transplantation, the rate of clinical events in these patients is far less. The observation that only a fraction of patients with anti-phospholipid antibodies experience thrombotic complications led to the description of anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome, defined by the presence of anti-phospholipid antibodies and a clinical history of thrombosis.

Anti-phospholipid antibodies include not only the lupus anticoagulant and anticardiolipin antibodies but also more recently recognized subgroups of anti-phospholipid antibodies (antibodies against beta-2-glycoprotein-I) and antibodies to phosphatidylserine, phosphatidylethanolamine, phosphatidylglycerol, phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylcholine, and anti-annexin-V.

Patients with anti-phospholipid antibodies in association with other autoimmune diseases, most commonly lupus, are classified as having secondary anti-phospholipid syndrome. Approximately 40% of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus have an anti-phospholipid (anti-cardiolipin) antibody (lupus anticoagulant). The presence of anti-phospholipid antibodies has been recognized as an important risk factor for early allograft failure[46].

However, risk factors for arterial thrombosis are not limited to anti-phospholipid antibodies and lupus anticoagulants. Other hypercoagulable states include FVL mutation[47], antithrombin deficiency[48], methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase mutation, and hyperhomocysteinemia[49]. Furthermore, infectious and inflammatory states such as polyarteritis nodosa[50], Takayasu arteritis[51], and Behcet disease[52] are associated with renal artery thrombosis. These diseases might still possibly endanger acute thrombosis of a transplanted renal artery.

The FVL mutation, characterized by activated protein C (APC) resistance, represents the most prevalent inherited thrombophilic disorder. It is present in approximately 5%-8% of the general population, observed in 20% of individuals experiencing a first venous thrombotic event, and identified in up to 50% of patients with a personal or family history of recurrent thrombosis[53].

A molecular aberration in the factor V gene has been identified as the cause of the majority of APC resistance cases[54]. Physiologically, APC in conjunction with its cofactor protein S regulates coagulation by proteolytically inactivating the activated coagulation factors V and VIII (Va and VIIIa)[55]. A single point mutation in the factor V gene, a guanine-to-adenine substitution at nucleotide position 1691 (G1691A), results in a variant factor V protein that is resistant to inac

The hypercoagulable condition associated with the FVL mutation exhibits variable penetrance[60]. While some carriers remain asymptomatic throughout their lives, others require the presence of additional risk factors, such as oral contraceptive use or anti-phospholipid antibodies, to precipitate a thromboembolic manifestation[61].

The FVL mutation has been associated with an increased risk of transplant renal vein thrombosis, with multiple cases reported in recipients who are FVL-positive across various studies[62-67]. Irish et al[63] identified a four-fold elevated risk of allograft thrombosis linked to FVL while noting that the mutation does not significantly increase the risk of arterial thrombosis, such as myocardial infarction, within this patient population. Therefore, the FVL mutation does not appear to confer an increased risk for arterial thrombosis.

The FVL mutation does not appear to predispose individuals to arterial thrombosis, including renal arterial thrombosis. Consistently, reports of renal arterial thrombosis in patients with the FVL mutation are exceedingly rare in the literature. Le Moine et al[68] documented a single case of renal artery thrombosis in a patient with heterozygous FVL while Klein et al[47] described another case of acute renal artery occlusion presenting as renal colic in an individual positive for FVL. Notably, the latter patient also tested positive for anti-phospholipid antibodies, suggesting that heterozygosity for FVL alone may be insufficient to induce renal arterial thrombosis. These observations underscore the variable penetrance of the FVL mutation and highlight the requirement for additional prothrombotic factors to precipitate such events.

In the context of renal transplantation, the donor kidney endothelium acquires a prothrombotic phenotype as a result of reperfusion injury, surgical trauma, inflammatory activation, and tissue factor expression, compounded by the recipient’s immune response. When this endothelial activation coincides with an inherited or acquired predisposition to hypercoagulability, the likelihood of thrombotic complications is substantially increased[69,70].

Donor-related risk factors reported in the literature include age over 60 years, very young donors under 5 years of age, marginal donors (e.g., multiple renal arteries, right kidney procurement), and pre-existing donor renal artery lesions such as atherosclerosis. An elevated risk of graft thrombosis has been documented in kidney transplant from elderly donors[12,71], likely attributable to donor hypotension combined with ischemia-reperfusion injury, which may promote procoagulant activity through cytokine release and the recipient’s immune response in atherosclerotic vessels[70]. Similarly, pediatric recipients receiving kidneys from cadaveric donors younger than 5 years exhibit a significantly higher incidence of thrombosis compared to those receiving grafts from older donors[72], a risk largely attributed to the marked size mismatch between donor and recipient vessels[73].

Historically, renal grafts with multiple arteries were considered to carry a higher risk of thrombosis[74]; however, this association appears less relevant in the modern transplant era[10,12-14,75-80] with reports of successful implantation even in grafts containing up to six arteries[81]. Accessory renal arteries are present in approximately 10%-20% of the population. Successful transplantation in such cases necessitates a highly skilled surgeon with comprehensive knowledge of renal arterial anatomical variations and advanced proficiency in microsurgical vascular reconstruction[81].

Regarding donor-related risk factors for graft thrombosis, Amézquita et al[73] suggested that the use of the right donor kidney as opposed to the left may predispose to early vascular thrombosis[73]. This association had been previously reported in earlier analyses[10]. Anatomical considerations largely account for this increased risk. The right kidney typically has a shorter renal vein and a longer renal artery, both of which present distinct technical challenges during transplantation. The longer artery is more susceptible to kinking while the shorter vein can complicate anastomosis. Furthermore, postoperative swelling whether due to ischemic injury, acute tubular necrosis, or urinary obstruction may result in compression of the renal vein by the graft itself[10,15,82]. The positioning of the right kidney is further compli

Transplantation-related factors include cold ischemia time of the donor kidney > 24 hours, immune induction protocol, and rejection reactions. Several studies with larger cohorts report an increased incidence of thrombosis associated with prolonged cold ischemia time, particularly when exceeding 24 hours[42,80,83,84]. Surgery-related risk factors are primarily defined by technical challenges during graft procurement, back-table preparation, and implantation that may compromise the arterial lumen and disrupt normal blood flow. These include donor artery intimal injury incurred during graft retrieval, suboptimal vascular anastomosis, particularly in small grafts, as well as misalignment, torsion, or kinking of the renal artery.

Although intimal injury is uncommon, Nerli et al[85] reported a case of renal artery thrombosis resulting from such damage that led to impaired intraoperative blood flow across the anastomosis. This underscores the importance of using atraumatic perfusion needles and equipment, carefully inspecting the cut vessel ends for injury, monitoring graft turgidity, and closely observing the appearance of the transplanted kidney during surgery[85,86].

In renal transplantation the two predominant arterial anastomotic techniques are the end-to-end anastomosis of the renal artery to the hypogastric artery and the end-to-side anastomosis to the external iliac artery[87]. The end-to-end approach is generally favored due to its technical simplicity and shorter operative duration as well as its advantage in preserving lower limb perfusion. However, it is associated with a higher incidence of stenosis compared with the end-to-side anastomosis[88]. Allograft positioning in kidney transplantation can be challenging and may lead to torsion, an early or late complication. This often causes arterial kinking, typically due to an excessively long renal artery twisting from graft or pelvic shifts[89].

Post-transplant graft thrombosis typically presents with a sudden decrease in urine output accompanied by severe pain and tenderness over the graft site. Thrombocytopenia may develop within hours due to platelet accumulation in the thrombus. Prompt investigation is essential as early detection may allow for corrective intervention, whereas delayed diagnosis or treatment often results in graft loss[6].

A Doppler ultrasound is a rapid, reliable, and noninvasive first-line modality for identifying renal artery or vein thrombosis[90,91], demonstrating absent flow in both the main and intrarenal arterial branches[92]. Characteristic findings include a rapid decline in systolic frequency shifts, a retrograde diastolic plateau in the main renal artery and its proximal branches, and the absence of venous Doppler signals. Additional modalities, such as angiography, scintigraphy, CT, and magnetic resonance imaging, may also be employed to detect or confirm vascular thrombosis[5].

Transplant renal artery thrombosis represents a surgical emergency with the only viable chance of salvaging the graft being prompt exploration and restoration of renal perfusion. Therapeutic approaches for acute transplant renal artery thrombosis include open surgical thrombectomy or endovascular interventions, including catheter-directed thrombolysis and pharmacomechanical thrombectomy with or without adjunctive angioplasty or stent placement.

The therapeutic role of catheter-directed thrombolysis and percutaneous thrombectomy in early transplant renal artery thrombosis has not been clearly established. However, successful outcomes have been documented following percu

The administration of thrombolytic agents during the early post-transplant period warrants careful consideration due to the heightened risk of severe hemorrhagic complications[1]. Hedegard et al[94] strongly advised the avoidance of thrombolytic therapy within the initial 2 weeks following graft implantation. In cases where endovascular thrombolysis was successfully employed to treat renal artery thrombosis, a comprehensive evaluation to identify and address the underlying cause was imperative to prevent recurrence[93]. In most cases by the time the diagnosis is confirmed, it is already too late for graft salvage, leaving graft nephrectomy the only viable intervention. Nephrectomy performed for renal artery thrombosis is associated with a high mortality rate, with sepsis constituting the principal cause of death[15].

Prevention plays a pivotal role in reducing the risk of vascular thrombosis and necessitates the integration of multiple measures. These include minimizing cold and warm ischemia times, ensuring meticulous surgical technique, such as excising traumatized segments of the donor artery during procurement, performing endarterectomy on atherosclerotic recipient vessels, and avoiding size mismatch between donor and recipient vessels, maintaining adequate intravascular volume to prevent perioperative hypotension, utilizing effective preservation solutions, and ensuring prompt, effective management of rejection. Collectively, these measures constitute key elements of a comprehensive prevention strategy[15,95].

Furthermore, identification and management of thrombophilic disorders may help prevent renal vascular thrombosis, potentially requiring routine screening and targeted therapy. However, no consensus guidelines exist. Screening is recommended for candidates with personal or family histories of thrombosis or recurrent catheter occlusions or those undergoing preemptive living donor transplantation.

The identification and management of thrombophilic conditions may serve as a preventive strategy against renal vascular thrombosis. This could involve routine screening and targeted therapy aimed at reducing the risk of thrombosis and subsequent graft loss; however, no consensus guidelines have yet been established. Previous studies suggest that laboratory evaluation should be considered for potential recipients with a personal or family history of thrombotic events, such as deep or superficial vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, thrombosed fistulas, or multiple occlusions of central venous dialysis catheters, or for patients undergoing preemptive transplantation with a living donor kidney[89].

Balancing the risk of thrombosis and hemorrhage is essential in recipients of renal transplants. In patients with known thrombophilia and prior thrombotic events, perioperative heparinization followed by long-term anticoagulation with warfarin has demonstrated favorable outcomes, including successful re-transplantation. However, the limited prospective randomized studies evaluating heparin use in this population have yielded conflicting results, underscoring the need for a standardized preoperative assessment of thrombotic and hemorrhagic risks and the development of consensus guidelines. Specifically, intravenous heparin has been effective in preventing graft thrombosis in patients with anti-phospholipid antibodies or congenital coagulation disorders. To minimize bleeding complications while maintaining anti-thrombotic efficacy, it is advisable to maintain the partial thromboplastin time ratio between 1.5 and 2.0. Long-term anticoagulation with warfarin or low-dose heparin should also be considered, targeting an international normalized ratio of approximately 2.5[89,96-98].

In our case the patient presented two major risk factors for renal graft thrombosis: A history of FVL mutation; and the presence of multiple donor renal arteries that created a technically challenging situation with increased surgical complexity and prolonged warm and cold ischemia times. The precise cause of the thrombosis cannot be definitively determined as a preventive strategy was implemented, including perioperative heparin anticoagulation, planned continuation of postoperative anticoagulation, and back-table transposition of the accessory renal artery into the main renal artery to reduce warm ischemia time. However, the back-table transposition of the inferior polar artery to the main renal artery may have contributed to the development of transplant renal artery thrombosis due to intimal injury.

The expertise of our surgical team in managing complex transplantation scenarios combined with prompt diagnosis and immediate re-exploration with thrombectomy enabled successful graft salvage.

We reported herein a rare case of acute transplant renal artery thrombosis in a patient with a hypercoagulable state due to FVL mutation, resulting in a long-term, well-functioning renal graft. Given the challenges associated in managing thrombosis and the high likelihood of graft loss, implementing comprehensive preventive strategies is essential. These measures should be particularly emphasized in patients with known additional thrombotic risk factors such as FVL mutation as the case of our patient. Early detection, prompt diagnosis, and timely intervention for post-transplant vascular complications, particularly renal transplant thrombosis, are critical to improving patient outcomes and enhancing graft survival.

| 1. | Dimitroulis D, Bokos J, Zavos G, Nikiteas N, Karidis NP, Katsaronis P, Kostakis A. Vascular complications in renal transplantation: a single-center experience in 1367 renal transplantations and review of the literature. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:1609-1614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Klepanec A, Balazs T, Bazik R, Madaric J, Zilinska Z, Vulev I. Pharmacomechanical thrombectomy for treatment of acute transplant renal artery thrombosis. Ann Vasc Surg. 2014;28:1314.e11-1314.e14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Budruddin M, Salmi IA, Shilpa R. Renal Allograft Thrombosis in the Early Post Transplant Period. O J Neph. 2013;3:148-151. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Balachandra S, Tejani A. Recurrent vascular thrombosis in an adolescent transplant recipient. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8:1477-1481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ponticelli C, Moia M, Montagnino G. Renal allograft thrombosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2009;24:1388-1393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Humar A, Matas AJ. Surgical complications after kidney transplantation. Semin Dial. 2005;18:505-510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Karassa FB, Avdikou K, Pappas P, Nakopoulou L, Kostakis A, Boletis JN. Late renal transplant arterial thrombosis in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus and antiphospholipid syndrome. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14:472-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Akbar SA, Jafri SZ, Amendola MA, Madrazo BL, Salem R, Bis KG. Complications of renal transplantation. Radiographics. 2005;25:1335-1356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Keller AK, Jorgensen TM, Jespersen B. Identification of risk factors for vascular thrombosis may reduce early renal graft loss: a review of recent literature. J Transplant. 2012;2012:793461. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bakir N, Sluiter WJ, Ploeg RJ, van Son WJ, Tegzess AM. Primary renal graft thrombosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996;11:140-147. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Ojo AO, Hanson JA, Wolfe RA, Agodoa LY, Leavey SF, Leichtman A, Young EW, Port FK. Dialysis modality and the risk of allograft thrombosis in adult renal transplant recipients. Kidney Int. 1999;55:1952-1960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Englesbe MJ, Punch JD, Armstrong DR, Arenas JD, Sung RS, Magee JC. Single-center study of technical graft loss in 714 consecutive renal transplants. Transplantation. 2004;78:623-626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Hernández D, Rufino M, Armas S, González A, Gutiérrez P, Barbero P, Vivancos S, Rodríguez C, de Vera JR, Torres A. Retrospective analysis of surgical complications following cadaveric kidney transplantation in the modern transplant era. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:2908-2915. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Sanni A, Wilson CH, Wyrley-Birch H, Vijayanand D, Navarro A, Sohrabi S, Jaques B, Rix D, Soomro N, Manas D, Talbot D. Donor risk factors for renal graft thrombosis. Transplant Proc. 2007;39:138-139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jordan ML, Cook GT, Cardella CJ. Ten years of experience with vascular complications in renal transplantation. J Urol. 1982;128:689-692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Churchill BM, Sheldon CA, McLorie GA, Arbus GS. Factors influencing patient and graft survival in 300 cadaveric pediatric renal transplants. J Urol. 1988;140:1129-1133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lijfering WM, de Vries AP, Veeger NJ, van Son WJ, Bakker SJ, van der Meer J. Possible contribution of cytomegalovirus infection to the high risk of (recurrent) venous thrombosis after renal transplantation. Thromb Haemost. 2008;99:127-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Rigotti P, Flechner SM, Van Buren CT, Payne WT, Kahan BD. Increased incidence of renal allograft thrombosis under cyclosporine immunosuppression. Int Surg. 1986;71:38-41. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Canadian Multicentre Transplant Study Group. A randomized clinical trial of cyclosporine in cadaveric renal transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:809-815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 424] [Cited by in RCA: 389] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Voss BL, Hamilton KK, Samara EN, McKee PA. Cyclosporine suppression of endothelial prostacyclin generation. A possible mechanism for nephrotoxicity. Transplantation. 1988;45:793-796. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Myers BD, Ross J, Newton L, Luetscher J, Perlroth M. Cyclosporine-associated chronic nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 1984;311:699-705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 897] [Cited by in RCA: 841] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Murray BM, Paller MS, Ferris TF. Effect of cyclosporine administration on renal hemodynamics in conscious rats. Kidney Int. 1985;28:767-774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 325] [Cited by in RCA: 306] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kahan BD. Cyclosporine nephrotoxicity: pathogenesis, prophylaxis, therapy, and prognosis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1986;8:323-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Myers BD. Cyclosporine nephrotoxicity. Kidney Int. 1986;30:964-974. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 300] [Cited by in RCA: 273] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Myers BD, Newton L, Boshkos C, Macoviak JA, Frist WH, Derby GC, Perlroth MG, Sibley RK. Chronic injury of human renal microvessels with low-dose cyclosporine therapy. Transplantation. 1988;46:694-703. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Myers BD, Sibley R, Newton L, Tomlanovich SJ, Boshkos C, Stinson E, Luetscher JA, Whitney DJ, Krasny D, Coplon NS. The long-term course of cyclosporine-associated chronic nephropathy. Kidney Int. 1988;33:590-600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 419] [Cited by in RCA: 381] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Van Buren D, Van Buren CT, Flechner SM, Maddox AM, Verani R, Kahan BD. De novo hemolytic uremic syndrome in renal transplant recipients immunosuppressed with cyclosporine. Surgery. 1985;98:54-62. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Mihatsch MJ, Thiel G, Basler V, Ryffel B, Landmann J, von Overbeck J, Zollinger HU. Morphological patterns in cyclosporine-treated renal transplant recipients. Transplant Proc. 1985;17:101-116. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Sommer BG, Innes JT, Whitehurst RM, Sharma HM, Ferguson RM. Cyclosporine-associated renal arteriopathy resulting in loss of allograft function. Am J Surg. 1985;149:756-764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Remuzzi G, Bertani T. Renal vascular and thrombotic effects of cyclosporine. Am J Kidney Dis. 1989;13:261-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Laupacis A. Complications of cyclosporine therapy. A comparison to azathioprine. Transpl Proc. 1983;15:2748-2753. |

| 32. | Merion RM, Calne RY. Allograft renal vein thrombosis. Transplant Proc. 1985;17:1746-1750. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Lourldas G, Botha JR, Meyers AM, Myburgh JA. Vascular complications in renal transplantation: The Johannesburg experience. Clin Transplant. 1987;1:240-245. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 34. | Jones RM, Murie JA, Ting A, Dunnill MS, Morris PJ. Renal vascular thrombosis of cadaveric renal allografts in patients receiving cyclosporin, azathioprine and prednisolone triple therapy. Clin Transplant. 1988;2:122-126. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 35. | Gruber SA, Chavers B, Payne WD, Fryd DS, Canafax DM, Simmons RL, Najarian JS, Matas A. Allograft renal vascular thrombosis--lack of increase with cyclosporine immunosuppression. Transplantation. 1989;47:475-478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Lozano M, Oppenheimer F, Cofan F, Rosinyol L, Mazzara R, Escolar G, Ordinas A. Platelet procoagulant activity induced in vivo by muromonab-CD3 infusion in uremic patients. Thromb Res. 2001;104:405-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Shankar R, Bastani B, Salinas-Madrigal L, Sudarshan B. Acute thrombosis of the renal transplant artery after a single dose of OKT3. Am J Nephrol. 2001;21:141-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Abramowicz D, Pradier O, De Pauw L, Kinnaert P, Mat O, Surquin M, Doutrelepont JM, Vanherweghem JL, Capel P, Vereerstraeten P. High-dose glucocorticosteroids increase the procoagulant effects of OKT3. Kidney Int. 1994;46:1596-1602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Abramowicz D, De Pauw L, Le Moine A, Sermon F, Surquin M, Doutrelepont JM, Ickx B, Depierreux M, Vanherweghem JL, Kinnaert P, Goldman M, Vereerstraeten P. Prevention of OKT3 nephrotoxicity after kidney transplantation. Kidney Int Suppl. 1996;53:S39-S43. [PubMed] |

| 40. | Murphy BG, Hill CM, Middleton D, Doherty CC, Brown JH, Nelson WE, Kernohan RM, Keane PK, Douglas JF, McNamee PT. Increased renal allograft thrombosis in CAPD patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1994;9:1166-1169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Snyder JJ, Kasiske BL, Gilbertson DT, Collins AJ. A comparison of transplant outcomes in peritoneal and hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2002;62:1423-1430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | McDonald RA, Smith JM, Stablein D, Harmon WE. Pretransplant peritoneal dialysis and graft thrombosis following pediatric kidney transplantation: a NAPRTCS report. Pediatr Transplant. 2003;7:204-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Gang S, Rajapurkar M. Vascular complications following renal transplantation. J Nephrol Ren Transpl. 2009;2:122-132. |

| 44. | Schafer AI. Hypercoagulable State. In: Willerson JT, Wellens HJJ, Cohn JN, Holmes DR, editors. Cardiovascular Medicine. London: Springer, 2007. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Morrissey PE, Ramirez PJ, Gohh RY, Yango AY, Kestin A, Madras PN, Monaco AP. Management of thrombophilia in renal transplant patients. Am J Transplant. 2002;2:872-876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Wagenknecht DR, Becker DG, LeFor WM, McIntyre JA. Antiphospholipid antibodies are a risk factor for early renal allograft failure. Transplantation. 1999;68:241-246. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Klein O, Bernheim J, Strahilevitz J, Lehmann J, Korzets Z. Renal colic in a patient with anti-phospholipid antibodies and factor V Leiden mutation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14:2502-2504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Miura K, Takahashi T, Takahashi I, Komatsu M, Tsuchida S, Mikami T, Suzuki T, Takahashi S, Takada G. Renovascular hypertension due to antithrombin deficiency in childhood. Pediatr Nephrol. 2004;19:1294-1296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Queffeulou G, Michel C, Vrtovsnik F, Philit JB, Dupuis E, Mignon F. Hyperhomocysteinemia, low folate status, homozygous C677T mutation of the methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase and renal arterial thrombosis. Clin Nephrol. 2002;57:158-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Templeton PA, Pais SO. Renal artery occlusion in PAN. Radiology. 1985;156:308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Teoh MK. Takayasu's arteritis with renovascular hypertension: results of surgical treatment. Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;7:626-632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Akpolat T, Akkoyunlu M, Akpolat I, Dilek M, Odabas AR, Ozen S. Renal Behçet's disease: a cumulative analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2002;31:317-337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Kujovich JL. Thrombophilia and thrombotic problems in renal transplant patients. Transplantation. 2004;77:959-964. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Dahlbäck B. Factor V gene mutation causing inherited resistance to activated protein C as a basis for venous thromboembolism. J Intern Med. 1995;237:221-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Huisman MV, Rosendaal F. Thrombophilia. Curr Opin Hematol. 1999;6:291-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Bertina RM, Koeleman BP, Koster T, Rosendaal FR, Dirven RJ, de Ronde H, van der Velden PA, Reitsma PH. Mutation in blood coagulation factor V associated with resistance to activated protein C. Nature. 1994;369:64-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2687] [Cited by in RCA: 2476] [Article Influence: 77.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Voorberg J, Roelse J, Koopman R, Büller H, Berends F, ten Cate JW, Mertens K, van Mourik JA. Association of idiopathic venous thromboembolism with single point-mutation at Arg506 of factor V. Lancet. 1994;343:1535-1536. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 300] [Cited by in RCA: 291] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Zöller B, Dahlbäck B. Linkage between inherited resistance to activated protein C and factor V gene mutation in venous thrombosis. Lancet. 1994;343:1536-1538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 283] [Cited by in RCA: 269] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Dahlbäck B. Activated protein C resistance and thrombosis: molecular mechanisms of hypercoagulable state due to FVR506Q mutation. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1999;25:273-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Greengard JS, Eichinger S, Griffin JH, Bauer KA. Brief report: variability of thrombosis among homozygous siblings with resistance to activated protein C due to an Arg-->Gln mutation in the gene for factor V. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1559-1562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Lillicrap D. Molecular diagnosis of inherited bleeding disorders and thrombophilia. Semin Hematol. 1999;36:340-351. [PubMed] |

| 62. | Heidenreich S, Dercken C, August C, Koch HG, Nowak-Göttl U. High rate of acute rejections in renal allograft recipients with thrombophilic risk factors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9:1309-1313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Irish AB, Green FR, Gray DW, Morris PJ. The factor V Leiden (R506Q) mutation and risk of thrombosis in renal transplant recipients. Transplantation. 1997;64:604-607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Guirguis N, Budisavljevic MN, Self S, Rajagopalan PR, Lazarchick J. Acute renal artery and vein thrombosis after renal transplant, associated with a short partial thromboplastin time and factor V Leiden mutation. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2000;30:75-78. [PubMed] |

| 65. | Wheeler MA, Taylor CM, Williams M, Moghal N. Factor V Leiden: a risk factor for renal vein thrombosis in renal transplantation. Pediatr Nephrol. 2000;14:525-526. [PubMed] |

| 66. | Wüthrich RP, Cicvara-Muzar S, Booy C, Maly FE. Heterozygosity for the factor V Leiden (G1691A) mutation predisposes renal transplant recipients to thrombotic complications and graft loss. Transplantation. 2001;72:549-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Wüthrich RP. Factor V Leiden mutation: potential thrombogenic role in renal vein, dialysis graft and transplant vascular thrombosis. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2001;10:409-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Le Moine A, Chauveau D, Grünfeld JP. Acute renal artery thrombosis associated with factor V Leiden mutation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1996;11:2067-2069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Key NS. Scratching the surface: endothelium as a regulator of thrombosis, fibrinolysis, and inflammation. J Lab Clin Med. 1992;120:184-186. [PubMed] |

| 70. | Irish A. Renal allograft thrombosis: can thrombophilia explain the inexplicable? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1999;14:2297-2303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Luna E, Cubero JJ, Hernández Gallego R, Barroso S, Caravaca F, García MC, Sánchez-Casado E. Evolution of suboptimal renal transplantations: experience of a single Spanish center. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:2394-2395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Singh A, Stablein D, Tejani A. Risk factors for vascular thrombosis in pediatric renal transplantation: a special report of the North American Pediatric Renal Transplant Cooperative Study. Transplantation. 1997;63:1263-1267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Amézquita Y, Méndez C, Fernández A, Caldes S, Pascual J, Muriel A, Burgos FJ, Marcén R, Ortuño J. Risk factors for early renal graft thrombosis: a case-controlled study in grafts from the same donor. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:2891-2893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Belli L, De Carlis L, Belli LS, Del Favero E, Puttini M, Aseni P, Rondinaria GF, Meroni A, Beati C. Thromboendarterectomy (TEA) in the recipient as a major risk of arterial complication after kidney transplantation. Int Angiol. 1989;8:206-209. [PubMed] |

| 75. | Benedetti E, Troppmann C, Gillingham K, Sutherland DE, Payne WD, Dunn DL, Matas AJ, Najarian JS, Grussner RW. Short- and long-term outcomes of kidney transplants with multiple renal arteries. Ann Surg. 1995;221:406-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Osman Y, Shokeir A, Ali-el-Dein B, Tantawy M, Wafa EW, el-Dein AB, Ghoneim MA. Vascular complications after live donor renal transplantation: study of risk factors and effects on graft and patient survival. J Urol. 2003;169:859-862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Mazzucchi E, Souza AA, Nahas WC, Antonopoulos IM, Piovesan AC, Arap S. Surgical complications after renal transplantation in grafts with multiple arteries. Int Braz J Urol. 2005;31:125-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | van Lieburg AF, de Jong MC, Hoitsma AJ, Buskens FG, Schröder CH, Monnens LA. Renal transplant thrombosis in children. J Pediatr Surg. 1995;30:615-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Ismail H, Kaliciński P, Drewniak T, Smirska E, Kamiński A, Prokurat A, Grenda R, Szymczak M, Chrupek M, Markiewicz M. Primary vascular thrombosis after renal transplantation in children. Pediatr Transplant. 1997;1:43-47. [PubMed] |

| 80. | Nagra A, Trompeter RS, Fernando ON, Koffman G, Taylor JD, Lord R, Hutchinson C, O'Sullivan C, Rees L. The effect of heparin on graft thrombosis in pediatric renal allografts. Pediatr Nephrol. 2004;19:531-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Orlando G, Gravante G, D'Angelo M, De Liguori Carino N, Di Cocco P, Scelzo C, Famulari A, Pisani F. A renal graft with six arteries and double pelvis. Transpl Int. 2008;21:609-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Rijksen JF, Koolen MI, Walaszewski JE, Terpstra JL, Vink M. Vascular complications in 400 consecutive renal allotransplants. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino). 1982;23:91-98. [PubMed] |

| 83. | Penny MJ, Nankivell BJ, Disney AP, Byth K, Chapman JR. Renal graft thrombosis. A survey of 134 consecutive cases. Transplantation. 1994;58:565-569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Pérez Fontán M, Rodríguez-Carmona A, García Falcón T, Tresancos C, Bouza P, Valdés F. Peritoneal dialysis is not a risk factor for primary vascular graft thrombosis after renal transplantation. Perit Dial Int. 1998;18:311-316. [PubMed] |

| 85. | Nerli RB, Uplenchwar S, Shetty G, Patil S, Rai S, Patel K, Saldanha R, Ghagane SC, Lote R, Rao S. Intraoperative Renal Artery Thrombosis of the Transplanted Kidney Secondary to Intimal Injury. Indian J Transplant. 2024;18:204-206. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 86. | Zhang J, Xue W, Tian P, Zheng J, Ding C, Li Y, Wang Y, Ding X. Diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for vascular complications after renal transplantation: a single-center experience in 2,304 renal transplantations. Front Transplant. 2023;2:1150331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Wickland E, Flye MW, Flye MW. Principles of organ transplantation. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1989: 687. |

| 88. | Groggel GC. Acute thrombosis of the renal transplant artery: a case report and review of the literature. Clin Nephrol. 1991;36:42-45. [PubMed] |

| 89. | Giakoustidis A, Antoniadis N, Giakoustidis D. Vascular Complications in Kidney Transplantation. In: Understanding the Complexities of Kidney Transplantation. InTech, 2011. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 90. | Schwenger V, Hinkel UP, Nahm AM, Morath C, Zeier M. Color doppler ultrasonography in the diagnostic evaluation of renal allografts. Nephron Clin Pract. 2006;104:c107-c112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Gao J, Ng A, Shih G, Goldstein M, Kapur S, Wang J, Min RJ. Intrarenal color duplex ultrasonography: a window to vascular complications of renal transplants. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26:1403-1418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Baxter GM. Ultrasound of renal transplantation. Clin Radiol. 2001;56:802-818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Rouvière O, Berger P, Béziat C, Garnier JL, Lefrançois N, Martin X, Lyonnet D. Acute thrombosis of renal transplant artery: graft salvage by means of intra-arterial fibrinolysis. Transplantation. 2002;73:403-409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Hedegard W, Saad WE, Davies MG. Management of vascular and nonvascular complications after renal transplantation. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2009;12:240-262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Andrassy J, Zeier M, Andrassy K. Do we need screening for thrombophilia prior to kidney transplantation? Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19 Suppl 4:iv64-iv68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | McIntyre JA, Wagenknecht DR. Antiphospholipid antibodies and renal transplantation: a risk assessment. Lupus. 2003;12:555-559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Alkhunaizi AM, Olyaei AJ, Barry JM, deMattos AM, Conlin MJ, Lemmers MJ, Bennett WM, Norman DJ. Efficacy and safety of low molecular weight heparin in renal transplantation. Transplantation. 1998;66:533-534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Friedman GS, Meier-Kriesche HU, Kaplan B, Mathis AS, Bonomini L, Shah N, DeFranco P, Jacobs M, Mulgaonkar S, Geffner S, Lyman N, Paraan C, Walsh C, Belizaire W, Tshibaka M. Hypercoagulable states in renal transplant candidates: impact of anticoagulation upon incidence of renal allograft thrombosis. Transplantation. 2001;72:1073-1078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/