Published online Mar 18, 2026. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v16.i1.114044

Revised: September 30, 2025

Accepted: December 3, 2025

Published online: March 18, 2026

Processing time: 125 Days and 17.8 Hours

Donor-specific antibodies (DSAs) against human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DQ are increasingly recognized as major contributors to antibody-mediated rejection (AMR) and graft failure in kidney transplantation. However, their clinical impact remains understudied in Morocco.

To evaluate the presence and implications of anti-HLA-DQ DSAs in Moroccan kidney transplant recipients.

We retrospectively analyzed the immunological profiles and clinical outcomes of kidney transplant recipients screened for anti-HLA antibodies between 2015 and 2020, who developed anti-HLA-DQ DSAs either before or after transplantation. Anti-HLA antibodies were identified using Luminex® single antigen bead techn

In the pre-transplant group (n = 6 with confirmed donor typing), patients with low to moderate median fluorescence intensity (MFI) anti-HLA-DQ DSAs (MFI 561-1581) underwent successful transplantation and maintained stable graft function under optimized immunosuppression. In contrast, in the post-transplant group (n = 6 with confirmed donor typing), the emergence of de novo anti-HLA-DQ DSAs was consistently associated with AMR, with MFI values reaching up to 19473, with biopsy-proven AMR in 5 of 6 cases and suspicion of AMR in 1 case. Two representative cases are detailed to illustrate the clinical impact of DQ DSAs: one patient developed high-level anti-DQB1*02 de novo DSA (MFI 12029) with persistent AMR after 5 years, while another developed anti-DQA1*05: 01 de novo DSA after an early AMR episode but maintained stable graft function after 5 years (creatinine 1.48 mg/dL).

Our findings underscore the clinical significance of anti-HLA-DQ DSAs in Moroccan kidney transplant recipients. While preformed DSAs with low immunogenicity may permit successful transplantation, de novo DSAs strongly correlate with AMR. Proactive monitoring, including routine DSA screening and HLA-DQ typing, could improve graft outcomes by enabling early intervention and better donor selection.

Core Tip: This retrospective study highlights the emerging role of donor-specific anti- human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DQ antibodies in kidney transplantation, an area where evidence from Moroccan populations remains scarce. Individual cases illustrate the clinical spectrum, but the findings derive from a systematic retrospective analysis. The study highlights the association between anti-HLA-DQ antibodies, antibody-mediated rejection, and graft outcomes, underscoring the need to integrate HLA-DQ monitoring into routine post-transplant follow-up and offering a valuable perspective for improving patient management in resource-limited settings.

- Citation: Guissouss O, Achiaou K, El Turk J, Mourachid A, Cheggali A, Medkouri G, Ramdani B, Benghanem Gharbi M, Taoudi Benchekroun M, Bennani S. Preformed vs de novo anti-human leukocyte antigens-DQ antibodies in kidney transplantation: A retrospective study. World J Transplant 2026; 16(1): 114044

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3230/full/v16/i1/114044.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v16.i1.114044

Chronic kidney disease progresses irreversibly to end-stage renal failure, necessitating renal replacement therapy. Kidney transplantation remains the gold standard, offering superior survival, quality of life, and cost-effectiveness compared to dialysis[1]. In Morocco, transplantation is limited by scarce donor availability, with most grafts originating from living donors and few from deceased[2].

Despite advances in immunosuppression and human leukocyte antigen (HLA) matching, graft rejection persists as a major challenge. While T-cell-mediated rejection has declined, antibody-mediated rejection (AMR), driven by donor-specific antibodies (DSAs) anti-HLA, has emerged as a critical barrier to long-term graft survival[3]. The HLA system, encoded by genes on chromosome 6, plays a major role in graft recognition. As highly polymorphic surface molecules, HLA antigens can trigger strong alloimmune responses[4]. DSAs, whether preformed or de novo, are strongly associated with AMR and graft failure. They are now considered well-established biomarkers of poor graft outcomes, notably associated with a higher incidence of humoral rejection, graft dysfunction, and reduced graft survival[5,6].

Among HLA class II antibodies, anti-HLA-DQ DSAs are increasingly recognized as clinically significant[7]. Historically overshadowed by HLA-DR due to linkage disequilibrium, HLA-DQ’s role became clearer with the advent of Luminex® single antigen bead (SAB) assays[8]. The DQA1 and DQB1 genes encoding HLA-DQ molecules are highly polymorphic, increasing the likelihood of the immune system developing specific antibodies directed against HLA-DQ alloantigen’s after pregnancy, blood transfusion, or transplantation[9]. Despite their prevalence and impact, no Moroccan studies have investigated anti-HLA-DQ DSAs, a gap this study aims to address.

Given the limited number of cases and the incomplete availability of clinical data, this study was conducted as a retrospective descriptive analysis. The objective was to explore antibody development patterns and their clinical relevance in kidney transplant recipients, based on available immunological profiles and case-specific follow-up, rather than to perform statistical comparisons.

Two distinct patient groups were identified between 2015 and 2020. This time frame was chosen to ensure methodological consistency, as the Luminex® technology for anti-HLA antibody detection was introduced at the Institute Pasteur in 2015. Limiting the inclusion to patients treated from that year onward ensured that all antibody screenings were performed using the same technique. The cut-off at 2020 was set to allow for at least five years of post-transplant follow-up.

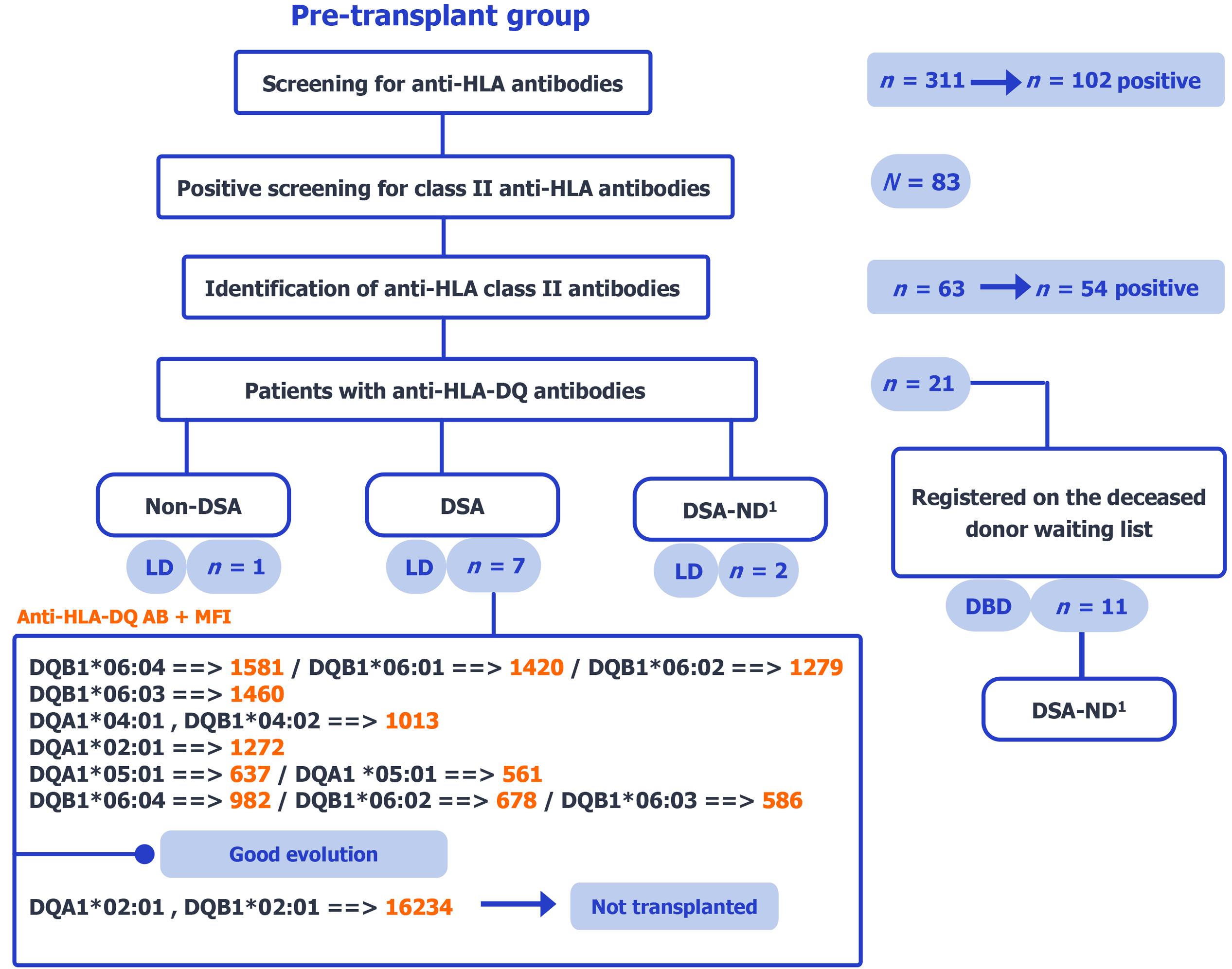

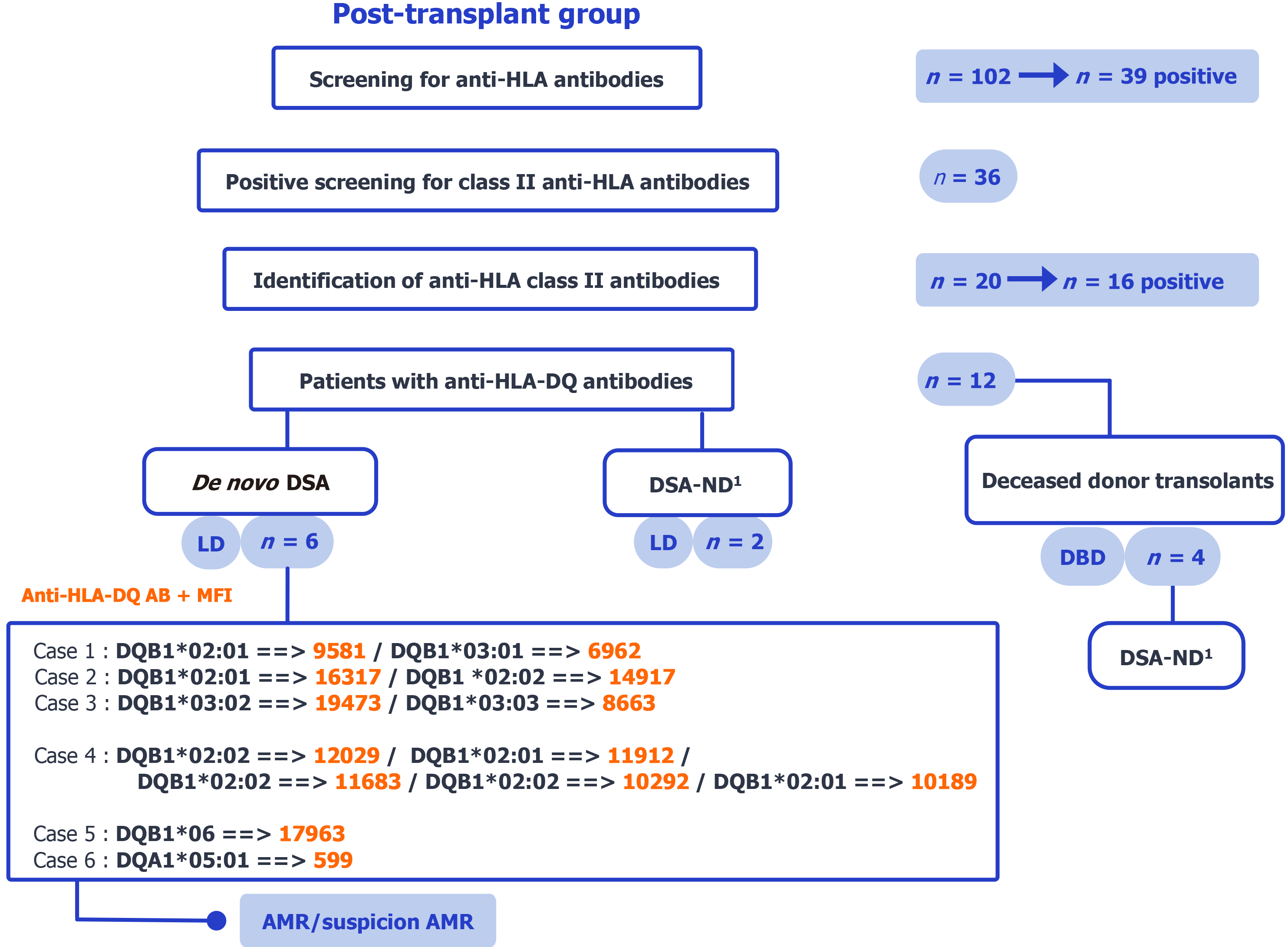

The study comprised two retrospective, case-based groups: (1) Candidates with pre-existing anti-HLA-DQ antibodies before transplantation (pre-transplant, n = 21); and (2) Recipients who developed de novo anti-HLA-DQ antibodies after transplantation (post-transplant, n = 12). In the pre-transplant group, among 311 screened candidates, 102 were anti-HLA positive (class II screen, n = 83); class II antibody identification was performed in 63 patients (54 positive), of whom 21 had anti-HLA-DQ antibodies (Figure 1). In the post-transplant group, among 102 screened recipients, 39 were anti-HLA positive (class II screen, n = 36); class II antibody identification was performed in 20 patients (16 positive), yielding 12 with anti-HLA-DQ antibodies (Figure 2). Only selected cases from this group were presented in detail due to limited clinical data availability.

Analysis sets: “Confirmed donor HLA-DQ” denotes availability of donor DQA1/DQB1 typing. The primary analysis was restricted to cases with confirmed donor HLA-DQ and DQ-DSA. Cases with confirmed donor HLA-DQ but non-DSA and those with undetermined donor HLA-DQ (undetermined donor HLA-DQ) were reported separately. This rule applies to both the pre-transplant and post-transplant groups. Denominators for each group are provided in Figures 1 and 2.

Within the pre-transplant group (n = 21), donor HLA-DQ status was confirmed (DQA1/DQB1 available) in 7 living-donor candidates with preformed DQ-DSA (6 transplanted with low/moderate MFI; 1 excluded due to high MFI), whereas 13 had undetermined donor HLA-DQ (2 living-donor; 11 on the deceased-donor waiting list with no donor typing available). Transplantation decisions for patients with preformed antibodies were made collaboratively by biologists and clinicians based on MFI levels. The selection process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Within the post-transplant group (n = 12), 6 living-donor recipients had confirmed donor HLA-DQ and de novo DQ-DSA, whereas 6 had undetermined donor HLA-DQ (2 living-donor; 4 deceased-donor). All included patients had developed de novo anti-HLA-DQ antibodies without pre-transplant sensitization, allowing assessment of their impact on graft outcomes. The selection process is illustrated in Figure 2.

Genomic DNA was extracted from blood samples using automated silica-based technology (EZ1; QIAGEN, Shanghai, China). Low-resolution typing of HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-DRB1 was performed via sequence-specific oligonucleotide polymerase chain reaction method (Lifecodes® HLA-SSO kit; Immucor, Inc., GA, United States) on the Luminex® xMAP® platform, analyzed with MatchIT DNA software. For HLA-DQ, both DQA1 and DQB1 loci were systematically typed to allow accurate characterization of DQ heterodimers.

Anti-HLA antibodies were detected using Luminex®-based SAB technology. Initial screening was performed with the LMX Class I/II DeLuxe screening kit (Immucor, Inc., GA, United States), with a positivity threshold of MFI > 1500. Specificity was determined using the Lifecodes® single antigen kit (Immucor, Inc., GA, United States) and analyzed with MatchIT Antibody software.

Positivity thresholds were categorized a priori as follows: Low (1500-5000), medium (5000-10000), and high (> 10000), consistent with ranges commonly used in published studies. Serum was tested neat, without routine dilution or prozone mitigation (e.g., ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid or acid treatment). Internal kit controls and lot-to-lot calibration provided by the manufacturers were systematically included, and results were validated according to laboratory quality control standards.

Continuous variables were summarized as median [interquartile range (IQR)]. Time-to-event intervals were defined as: (1) Transplant - DSA (from the transplant date to the first detection of de novo anti-HLA-DQ DSA); and (2) DSA - AMR (from the first DSA detection to biopsy-proven AMR). Intervals were calculated and reported in months. Because biopsy dates were unavailable for four patients and one case had AMR preceding DSA, case-series-level median/IQR for DSA - AMR were not reported.

In the pre-transplant group, six patients with preformed anti-HLA-DQ DSAs underwent kidney transplantation following multidisciplinary evaluation. All six patients had low to moderate MFI levels and received optimized immunosuppressive therapy. Their post-transplant outcomes were favorable, with stable graft function and no clinical evidence of rejection during follow-up.

Among the patients who developed anti-HLA-DQ de novo DSAs, six clinical cases were identified for their immunological and clinical relevance. Table 1 provides an overview of these patients, including key immunological characteristics and post-transplant outcomes.

| Clinical case | Sex | Age | Graft origin/relationship/transplantation date | HLA typing | Immunizing events | Crossmatch | Post-transplant antibodies to HLA I/II | Rejection diagnosis |

| 1 | Male | 52 | LD/spouse/transplanted in 2013 | R: A*23/A*33; B*15/B*44; DRB1*01/DRB1*15; DQB1: NT | None: Not immunized pre-transplant | Negative | 3 years post TR: Only DSA anti HLA-DQ de novo; DQB1*02:01 ==> MFI 9581; DQB1*03:01 ==> MFI 6962 | Proven humoral rejection (biopsy) |

| D: A*01/A*02; B*07/B*08; DRB1*03/NT; DQB1*02/DQB1*03 | ||||||||

| 2 | Male | 49 | LD/mother/transplanted in 2014 | R: A*02/NT; B*38/B*52; DRB1*08/DRB1*15; DQB1*06/DQB1*06 | None: Not immunized pre-transplant | Negative | 3 years post TR: Only DSA anti HLA-DQ de novo; DQB1*02:01 ==> MFI 16317; DQB1*02:02 ==> MFI 14917 | Proven humoral rejection (biopsy) |

| D: A*02/A*29; B*38/B*45; DRB1*08/DRB1*09; DQB1*02/DQB1*06 | ||||||||

| 3 | Female | 25 | LD/mother/transplanted in 2013 | R: A*03/A*68; B*14/NT; DRB1*11/DRB1*11; DQB1*03/NT | 2 transfusions: Not immunized pre-transplant | Negative | 6 years post TR: DSA anti HLA-DQ de novo; DQB1*03:02 ==> MFI 19473; DQB1*03:03 ==> MFI 8663 Associated with DSA A2 ==> MFI 7004 | Proven humoral rejection (biopsy) |

| D: A*02/A*68; B*14/B*21; DRB1*07/DRB1*11; DQB1*03/NT | ||||||||

| 4 | Male | 40 | LD/spouse/transplanted in December 2025 | R: A*24/A*29; B*44/B*50; DRB1*15/DRB1*15; DQB1*06/DQB1*06 | None: DSA anti DR4 (MFI 123) | Negative | 4 years post TR: Only DSA anti HLA-DQ de novo; MFI 10189 < DQB1*02 < MFI 12029 | Proven humoral rejection (biopsy) |

| D: A*01/A*02; B*08/B*18; DRB1*03/DRB1*04; DQB1*02/DQB1*04 | ||||||||

| 5 | Male | 55 | LD/sister/transplanted in 2016 | R: A*68/NT; B*18/NT; DRB1*02/NT; DQB1*02/NT | None: Not immunized pre-transplant | Negative | 17 months post TR: DSA anti HLA-DQ de novo; DQB1*06 ==> MFI 17963 Associated with: MFI 4870 < DSA A*66 < MFI 14271; DSA B*27 ==> MFI 19112 | Proven humoral rejection (biopsy) |

| D: A*68/A*66; B*18/B*27; DRB1*03/DRB1*15; DQB1*02/DQB1*06 | ||||||||

| 6 | Female | 54 | LD /sister/transplanted in November 2016 | R: A*01/A*02; B*07/B*50; DRB1*03/NT; DQB1: NT | 2 transfusions/2 pregnancies: A32 (MFI 1600), DR16 (MFI 1103) | Negative | 6 months post TR: Only DSA anti HLA-DQ de novo; DQA1*05:01 ==> MFI 599 | Suspicion of humoral rejection |

| D: A*24/A*30; B*13/B*51; DRB1*07/DRB1*11; DQB1*02/DQB1*03; DQA1*02/DQA1*05 |

Across the six patients, the median time from transplantation to the first de novo anti-HLA-DQ DSA was 36 months (IQR 17-48); range 6-72 months. Due to limited availability of clinical documentation for four of the cases, only two patients (case 4 and case 6) are detailed in the following section. These cases were selected based on the completeness of clinical and histological follow-up. They illustrate distinct patterns of AMR associated with anti-HLA-DQ de novo DSAs.

A 40-year-old male with end-stage renal disease of unknown etiology, with a body mass index of 24.6 kg/m2, received a living-donor kidney from his ABO-compatible wife despite HLA mismatches (donor: DQB1*02/04; recipient: DQB1*06/06). Pre-transplant Luminex testing detected anti-DR4 DSA (MFI 123) but no class I antibodies. Initial immu

| Date (post-transplant) | Glomerulitis | Interstitial inflammation | Tubulitis | Intimal arteritis | Chronic glomerulopathy | Mesangial matrix expansion | Total interstitial inflammation | Interstitial fibrosis | Tubular atrophy | Vascular intimal fibrous thickening | Peritubular capillaritis | Other parenchymal tubular lesions | Arteriolar hyalinosis | C4d | Conclusion |

| January 2016 (day 11) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NR | 0 | 0 | NR | 0 | 0 | Negative | Isolated tubular epithelial lesion |

| April 2019 (4 years) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NR | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | NR | 1 | Positive | Active ABMR |

| January 2020 (5 years) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | NR | 2 | Positive (focal) | Active ABMR |

A 54-year-old female with end-stage renal disease from obstructive nephropathy (body mass index 23.2 kg/m2) received a living-donor kidney from her sister. Pre-transplant sensitization history included transfusions and pregnancies, with anti-A*32 (MFI 1600) and anti-DRB1*16 (MFI 1103) antibodies. Initial immunosuppressive treatment consisted of tacrolimus (4 mg × 2/day), mycophenolate mofetil (1 g × 2/day), prednisone (30 mg/day), and thymoglobulin induction (day 1 and day 5). Tacrolimus trough targets were maintained between 8-10 ng/mL during the first months and 5-8 ng/mL thereafter. Corticosteroids were progressively tapered to 5 mg/day at 1 year.

At day 33 post-transplant, the patient presented a delayed recovery of graft function with a serum creatinine of 3.99 mg/dL. The biopsy showed acute tubular necrosis (C4d+), suggesting acute humoral rejection. The episode was managed with pulse intravenous corticosteroids. At 6 months, a worsening of renal function was observed (serum creatinine of 1.7 mg/dL) with the appearance of de novo anti-HLA-DQ DSA (DQA1*05:01 MFI 599). The second renal biopsy demonstrated mild interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy associated with arteriolar hyalinosis, without histological signs of rejection. At 5 years, renal function remained stable (serum creatinine of 1.48 mg/dL) under the same initial immunosuppressive treatment (tacrolimus, mycophenolate mofetil, and prednisone), without notable clinical events. The histological results are summarized in Table 3.

| Date (post-transplant) | Glomerulitis | Interstitial inflammation | Tubulitis | Intimal arteritis | Chronic glomerulopathy | Mesangial matrix expansion | Interstitial fibrosis | Tubular atrophy | Vascular intimal fibrous thickening | Peritubular capillaritis | Arteriolar hyalinosis | C4d | Conclusion |

| December 2016 (day 33) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Positive | Acute tubular necrosis with C4d positivity (suspicion of AMR) |

| May 2017 (6 months) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Positive | Mild IFTA with arteriolar hyalinosis, no rejection |

Studies report that 15%-25% of kidney transplant recipients develop de novo DSA within five years, correlating with < 40% 10-year graft survival[10]. This underscores the critical role of de novo DSA in renal allograft dysfunction, as also emphasized in the most recent Banff 2022 consensus and the recommendations from the sensitization in transplantation: Assessment of risk working group[11,12]. Among rejection-inducing antibodies, those targeting HLA-DQ antigens have garnered increasing attention due to their high incidence and strong association with AMR and graft loss[13]. Multiple studies highlight the detrimental impact of anti-HLA-DQ antibodies. Carta et al[9] confirmed that anti-HLA-DQ de novo DSA directly correlates with rejection, emphasizing their predominance among post-transplant antibodies. Willicombe et al[14] found that 54.3% of de novo DSA-positive patients (n = 505) had anti-HLA-DQ antibodies, which significantly increased risks of AMR, transplant glomerulopathy, and graft failure (P < 0.0001). Notably, HLA-DQ/DR incompatibility heightened class II DSA development (P = 0.001). The ability of HLA-DQ antibodies to activate complement further exacerbates graft damage. Arreola-Guerra et al[15] demonstrated that anti-HLA-DQ antibodies independently predicted complement component 1q (C1q)-binding capacity (odds ratio = 9.82, P < 0.001), suggesting a potent complement-fixing role. Similarly, Freitas et al[16] reported that complement-fixing anti-DQ DSAs reduced 5-year graft survival by 30% (P = 0.003) and increased rejection risks (22%-36%, P < 0.01). Chronic AMR and accelerated graft deterioration are strongly linked to anti-DQ de novo DSAs. Lee et al[17] observed chronic AMR predominantly in patients with anti-DQ de novo DSAs (P < 0.05). DeVos et al[18] noted that 3-year graft survival plummeted to 52% when anti-HLA-DQ DSAs coexisted with non-DQ antibodies, compared to 92%-94% in controls.

Our retrospective findings align with previously published observations. In particular, Thammanichanond et al[19] reported a kidney transplant recipient who, despite an initial absence of reactive antibodies, developed AMR two years post-transplant, associated with strong anti-HLA-DQ2 DSAs (MFI > 10000). C1q analysis revealed preferential complement fixation on the DQA1*05:01-DQB1*02:01 molecule (MFI 22462), confirming the pathogenic potential of these antibodies. These findings are consistent with our own clinical observations: Case 4 involved DSAs against DQB1*02, and case 6 presented anti-DQA1*05:01 antibodies, both associated with graft dysfunction. In this case, the antibody was detected at low MFI (599) in the context of suspected AMR. Although this value was below our predefined positivity threshold, the episode was considered clinically relevant given the concordant C4d positivity and subsequent graft evolution. This apparent discrepancy may reflect sampling time, technical variability of SAB assays, or the contribution of non-HLA antibodies, highlighting that low-level signals near the positivity threshold should be interpreted with caution when clinical and histological evidence of AMR is present.

HLA-DQ DSAs were the most frequent post-transplant antibodies in our group of patients and were consistently linked to unfavorable graft outcomes. While preformed DSAs (depending on MFI levels) did not preclude successful transplantation, our results emphasize the importance of post-transplant DSA monitoring to anticipate AMR, in line with recent international consensus guidelines from the European Society for Organ Transplantation[20]. While HLA-DQ’s immunogenicity is well-documented, its mechanistic underpinnings remain unclear. Current gaps underscore the need for HLA-DQA1/DQB1 typing in donor-recipient matching and proactive post-transplant DSA monitoring, even in asymptomatic patients. Further research should elucidate HLA-DQ’s immunodominance and refine desensitization strategies.

As accurate identification of DQ-DSA requires consideration of both DQA1 and DQB1 chains, we note that in our patient series, donor-recipient typing systematically included both DQA1 and DQB1 loci, which allowed accurate attribution of DSA specificity. For clarity, DQA1 results were reported explicitly in case 6, while for other cases only DQB1 data were shown in the summary table, as the detected DSAs were directed exclusively against DQB1.

A limitation of this case study is the incomplete clinical follow-up for several cases studied, combined with the modest number of patients with anti-HLA-DQ DSAs. These constraints prevented statistical analysis and limited the extent of clinical correlations that could be drawn. To fully evaluate the impact of anti-HLA-DQ DSAs in the Moroccan kidney transplant population, larger studies with comprehensive clinical and immunological data will be required. Meanwhile, we adopted a descriptive, case-based approach using the available data. A further limitation of our study is the absence of functional assays evaluating the pathogenic potential of DSAs. Complement-binding tests (C1q/complement component 3d) and IgG subclass determination, which can discriminate between complement-fixing (IgG1, IgG3) and non-complement-fixing (IgG2, IgG4) antibodies, were not available in our setting. Although stored sera could theoretically allow retrospective testing, such analyses are not currently feasible due to technical constraints. This lack of mechanistic characterization may limit the interpretation of the observed association between anti-HLA-DQ de novo DSAs and AMR. Nevertheless, previous studies have consistently shown that anti-HLA-DQ antibodies are frequently complement-fixing (IgG1/IgG3) and strongly associated with graft injury[15,16], which supports our interpretation despite this limitation.

Given the high prevalence and clinical impact of anti-HLA-DQ antibodies, integrating HLA-DQ typing into routine donor-recipient matching may reduce de novo DSA incidence and rejection risk. Although underexplored compared to anti-HLA class I and DR DSAs, growing evidence underscores the pathogenic role of anti-HLA-DQ antibodies in graft failure. Early detection and monitoring may be pivotal in improving long-term outcomes. Further research is needed to elucidate their mechanisms of action and reinforce their place in transplant immunology.

We thank all the authors for their contributions, as well as our team at the Human Leukocyte Antigen Laboratory for their excellent technical assistance, and the participating members of the nephrology department at Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Casablanca for providing us with clinical follow-up data. We thank Dr. Sayeh Ezzikouri (Research Director, Virology Unit, Head of Viral Hepatitis and Human Immunodeficiency Virus Laboratory, Pasteur Institute) who made a critical revision of our manuscript. This work was carried out with the support of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique et Technique.

| 1. | Gondran-Tellier B, Baboudjian M, Lechevallier E, Boissier R. [Renal transplantation, for whom, why and how ?]. Prog Urol. 2020;30:976-981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Noto-Kadou-Kaza B, Sabi KA, Imangue G, Al-Torayhi MH, Amekoudi EY, Tsevi CM, Zamd M, Medkouri G, Benghanem MG, Ramdani B. [Kidney transplantation in Morocco: are hemodialysis caretakers well informed?]. Pan Afr Med J. 2014;19:365. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Crespo M, Zárraga S, Alonso Á, Beneyto I, Díaz Corte C, Fernandez Rodriguez AM, Franco A, Hernández D, González-Roncero FM, Jiménez Martín C, Jimeno L, Lauzurica Valdemoros LR, Llorente S, Mazuecos A, Osuna A, Ramos JP, Rodríguez Benot A, Ruiz San Millán JC, Sánchez Fructuoso A, Torregrosa JV, Guirado L; GREAT Study Group and Spanish Network for Research in Renal Diseases (REDINREN, RED16/0009). Monitoring of Donor-specific Anti-HLA Antibodies and Management of Immunosuppression in Kidney Transplant Recipients: An Evidence-based Expert Paper. Transplantation. 2020;104:S1-S12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Montgomery RA, Tatapudi VS, Leffell MS, Zachary AA. HLA in transplantation. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2018;14:558-570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Fidler SJ, Irish AB, Lim W, Ferrari P, Witt CS, Christiansen FT. Pre-transplant donor specific anti-HLA antibody is associated with antibody-mediated rejection, progressive graft dysfunction and patient death. Transpl Immunol. 2013;28:148-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Süsal C, Wettstein D, Döhler B, Morath C, Ruhenstroth A, Scherer S, Tran TH, Gombos P, Schemmer P, Wagner E, Fehr T, Živčić-Ćosić S, Balen S, Weimer R, Slavcev A, Bösmüller C, Norman DJ, Zeier M, Opelz G; Collaborative Transplant Study Report. Association of Kidney Graft Loss With De Novo Produced Donor-Specific and Non-Donor-Specific HLA Antibodies Detected by Single Antigen Testing. Transplantation. 2015;99:1976-1980. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tambur AR. HLA-DQ antibodies: are they real? Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2016;21:441-446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Al Attas R, Al Abduladheem D, Shawhatti AA, Lopez R, Liacini A, AlZahrani S, Akkari K, Hasan N, Alabadi A. The dilemma of DQ HLA-antibodies. Hum Immunol. 2015;76:324-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Carta P, Di Maria L, Caroti L, Buti E, Antognoli G, Minetti EE. Anti-human leukocyte antigen DQ antibodies in renal transplantation: Are we underestimating the most frequent donor specific alloantibodies? Transplant Rev (Orlando). 2015;29:135-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Aubert O, Loupy A, Hidalgo L, Duong van Huyen JP, Higgins S, Viglietti D, Jouven X, Glotz D, Legendre C, Lefaucheur C, Halloran PF. Antibody-Mediated Rejection Due to Preexisting versus De Novo Donor-Specific Antibodies in Kidney Allograft Recipients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:1912-1923. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 211] [Article Influence: 23.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Naesens M, Roufosse C, Haas M, Lefaucheur C, Mannon RB, Adam BA, Aubert O, Böhmig GA, Callemeyn J, Clahsen-van Groningen M, Cornell LD, Demetris AJ, Drachenberg CB, Einecke G, Fogo AB, Gibson IW, Halloran P, Hidalgo LG, Horsfield C, Huang E, Kikić Ž, Kozakowski N, Nankivell B, Rabant M, Randhawa P, Riella LV, Sapir-Pichhadze R, Schinstock C, Solez K, Tambur AR, Thaunat O, Wiebe C, Zielinski D, Colvin R, Loupy A, Mengel M. The Banff 2022 Kidney Meeting Report: Reappraisal of microvascular inflammation and the role of biopsy-based transcript diagnostics. Am J Transplant. 2024;24:338-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 161] [Article Influence: 80.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lefaucheur C, Louis K, Morris AB, Taupin JL, Nickerson P, Tambur AR, Gebel HM, Reed EF; STAR 2022 Working Group. Clinical recommendations for posttransplant assessment of anti-HLA (Human Leukocyte Antigen) donor-specific antibodies: A Sensitization in Transplantation: Assessment of Risk consensus document. Am J Transplant. 2023;23:115-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Meneghini M, Tambur AR. HLA-DQ antibodies in alloimmunity, what makes them different? Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2023;28:333-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Willicombe M, Brookes P, Sergeant R, Santos-Nunez E, Steggar C, Galliford J, McLean A, Cook TH, Cairns T, Roufosse C, Taube D. De novo DQ donor-specific antibodies are associated with a significant risk of antibody-mediated rejection and transplant glomerulopathy. Transplantation. 2012;94:172-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Arreola-Guerra JM, Morales-Buenrostro LE, Granados J, Castelán N, de Santiago A, Arvizu A, Gonzalez-Tableros N, López M, Vilatobá M, Alberú J. Anti-HLA-DQ antibodies are highly and independently related to the C1q-binding capacity of HLA antibodies. Transpl Immunol. 2017;41:10-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Freitas MC, Rebellato LM, Ozawa M, Nguyen A, Sasaki N, Everly M, Briley KP, Haisch CE, Bolin P, Parker K, Kendrick WT, Kendrick SA, Harland RC, Terasaki PI. The role of immunoglobulin-G subclasses and C1q in de novo HLA-DQ donor-specific antibody kidney transplantation outcomes. Transplantation. 2013;95:1113-1119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lee H, Min JW, Kim JI, Moon IS, Park KH, Yang CW, Chung BH, Oh EJ. Clinical Significance of HLA-DQ Antibodies in the Development of Chronic Antibody-Mediated Rejection and Allograft Failure in Kidney Transplant Recipients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e3094. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | DeVos JM, Gaber AO, Knight RJ, Land GA, Suki WN, Gaber LW, Patel SJ. Donor-specific HLA-DQ antibodies may contribute to poor graft outcome after renal transplantation. Kidney Int. 2012;82:598-604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Thammanichanond D, Tammakorn C, Worawichawong S, Kantachuvesiri S. Antibody-Mediated Rejection Due to Donor-Specific HLA-DQB1 and DQA1 Antibodies After Kidney Transplantation: A Case Report. Transplant Proc. 2020;52:1931-1936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | van den Broek DAJ, Meziyerh S, Budde K, Lefaucheur C, Cozzi E, Bertrand D, López Del Moral C, Dorling A, Emonds MP, Naesens M, de Vries APJ; ESOT Working Group Subclinical DSA Monitoring. The Clinical Utility of Post-Transplant Monitoring of Donor-Specific Antibodies in Stable Renal Transplant Recipients: A Consensus Report With Guideline Statements for Clinical Practice. Transpl Int. 2023;36:11321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/