Published online Mar 22, 2016. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v6.i1.143

Peer-review started: September 6, 2015

First decision: October 27, 2015

Revised: November 19, 2015

Accepted: January 5, 2016

Article in press: January 7, 2016

Published online: March 22, 2016

Processing time: 200 Days and 12.2 Hours

AIM: To provide a comprehensive overview of clinical studies on the clinical picture of Internet-use related addictions from a holistic perspective. A literature search was conducted using the database Web of Science.

METHODS: Over the last 15 years, the number of Internet users has increased by 1000%, and at the same time, research on addictive Internet use has proliferated. Internet addiction has not yet been understood very well, and research on its etiology and natural history is still in its infancy. In 2013, the American Psychiatric Association included Internet Gaming Disorder in the appendix of the updated version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-5) as condition that requires further research prior to official inclusion in the main manual, with important repercussions for research and treatment. To date, reviews have focused on clinical and treatment studies of Internet addiction and Internet Gaming Disorder. This arguably limits the analysis to a specific diagnosis of a potential disorder that has not yet been officially recognised in the Western world, rather than a comprehensive and inclusive investigation of Internet-use related addictions (including problematic Internet use) more generally.

RESULTS: The systematic literature review identified a total of 46 relevant studies. The included studies used clinical samples, and focused on characteristics of treatment seekers and online addiction treatment. Four main types of clinical research studies were identified, namely research involving (1) treatment seeker characteristics; (2) psychopharmacotherapy; (3) psychological therapy; and (4) combined treatment.

CONCLUSION: A consensus regarding diagnostic criteria and measures is needed to improve reliability across studies and to develop effective and efficient treatment approaches for treatment seekers.

Core tip: Internet addiction has appeared as new mental health concern. To date, reviews have focused on clinical and treatment studies of Internet addiction and Internet Gaming Disorder, limiting the analysis to a specific diagnosis of a potential disorder that has not yet been officially recognised, rather than a comprehensive investigation of Internet-use related addictions (including problematic Internet use) more generally. This systematic literature review outlines and discusses the current empirical literature base for clinical studies of Internet addiction and problematic Internet use. A total of 46 relevant studies on treatment seeker characteristics, psychopharmacotherapy, psychological therapy, and combined treatment were identified.

- Citation: Kuss DJ, Lopez-Fernandez O. Internet addiction and problematic Internet use: A systematic review of clinical research. World J Psychiatr 2016; 6(1): 143-176

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v6/i1/143.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v6.i1.143

Over the last 15 years, the number of Internet users has increased by 1000%[1], and at the same time, research on addictive Internet use has proliferated. Internet addiction has not yet been understood very well, and research on its etiology and natural history is still in its infancy[2]. Currently, it is estimated that between 0.8% of young individuals in Italy[3] and 8.8% of Chinese adolescents[4] are affected. The reported higher prevalence rates in China suggest Internet addiction is a serious problem in China, and the country has acknowledged Internet addiction as official disorder in 2008[5].

A comprehensive systematic review of epidemiological research of Internet addiction for the last decade[6] indicated Internet addiction is associated with various risk factors, including sociodemographic variables (including male gender, younger age, and higher family income), Internet use variables (including time spent online, using social and gaming applications), psychosocial factors (including impulsivity, neuroticism, and loneliness), and comorbid symptoms (including depression, anxiety, and psychopathology in general), suggesting these factors contribute to an increased vulnerability for developing Internet-use related problems. Despite the gradually increasing number of studies concerning Internet addiction, classification is a contentious issue as a total of 21 different assessment instruments have been developed to date, and these are currently used to identify Internet addiction in both clinical and normative populations[6]. Conceptualisations vary substantially and include criteria derived from pathological gambling, substance-related addictions and the number of problems experienced. In addition to this, the cut-off points utilised for classification differ significantly, which impedes research and cultural cross-comparisons and limits research reliability.

Increasing research efforts on Internet addiction have led the American Psychiatric Association (APA) to include Internet Gaming Disorder in the appendix of the updated version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-5) in 2013 as condition that requires further research before it can be accepted for inclusion in the main manual[7]. This has resulted in researchers commencing efforts to reach an international consensus for assessing Internet Gaming Disorder using the new DSM-5 approach based on an international expert panel[8]. However, various limitations to this recently proposed “consensus” have been identified, including the lack of a representative international community of experts in the field, the voting method used to arrive at the consensus, the criteria and nosology identified, lack of critical measurement of the disorder and lack of field testing[9]. For the purpose of a comprehensive and inclusive understanding of the potential disorder, in this systematic literature review, Internet addiction will be referred to as encompassing Internet-use related addictions and problematic Internet use, including Internet Gaming Disorder. It is argued that until this concept is understood more fully (including nosology, etiology and diagnostic criteria), limiting our understanding of Internet-use related addictions to Internet gaming-related problems does neither pay sufficient respect to the affected individuals’ personal experience nor to the variety of online behaviours that can be engaged in excessively online. For example, other potential online addictions and Internet-use related disorders have been recently reviewed[10], suggesting that limiting a diagnosis to online gaming exclusively misses out many cases of individuals who experience negative consequences and significant impairment due to their Internet use-related behaviours.

For some individuals, their online behaviours are problematic and they require professional help as they cannot cope with their experiences by themselves, suggesting treatment is necessary. Based on in-depth interviews with 20 Internet addiction treatment experts from Europe and North America, Kuss and Griffiths[11] found that in inpatient and outpatient clinical settings, Internet addiction and Internet-use related problems are associated with significant impairment and distress for individuals, which have been emphasised as the criteria demarcating mental disorders[12]. This suggests that in the clinical context, Internet addiction can be viewed as mental disorder requiring professional treatment if the individual presents with significant levels of impairment. Psychotherapists treating the condition indicate the symptoms experienced by the individuals presenting for treatment appear similar to traditional substance-related addictions, including salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict and relapse[11]. This view is reflected by patients who seek treatment for their excessive gaming[13].

In 2002, the South Korean government-funded National Information Society Agency has opened the first Internet addiction prevention counselling centre worldwide, and has since developed large-scale projects (including prevention, training, counselling, treatment, and policy formulation) to tackle the pervasive problem of technology overuse[14]. Across the United States and Europe, Internet addiction treatment is not funded by the government, often leaving individuals seeking help either for other primary disorders or through private organisations, although new clinical centres that specialise in treating Internet-use related problems are being developed[15]. Based on the available evidence, recent research furthermore suggests that the best approach to treating Internet addiction is an individual approach, and a combination of psychopharmacotherapy with psychotherapy appears most efficacious[16].

To date, reviews have focused on clinical and treatment studies of Internet addiction[16-19] and Internet Gaming Disorder[2]. This arguably limits the analysis to a specific diagnosis of a potential disorder that has not yet been officially recognised in the Western world, rather than a comprehensive and inclusive investigation of Internet-use related addictions (including problematic Internet use) more generally. Previous reviews relied on overly restrictive inclusion criteria, and this has led to ambiguities in the conceptualisation of the problem, and consequently resulted in limitations regarding both validity and reliability. In order to overcome these problems, the aim of this literature review is to provide a comprehensive overview of clinical studies on the more inclusive clinical picture of Internet-use related addictions from a holistic perspective.

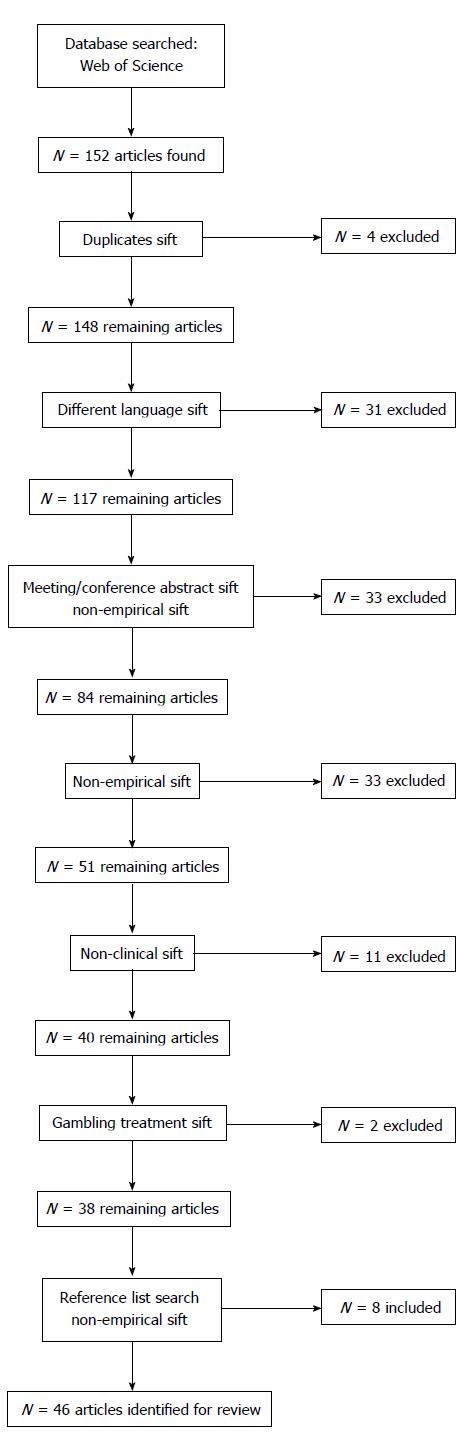

Between July and August 2015, a literature search was conducted using the database Web of Science. This database is more comprehensive than other commonly used databases, such as PsycINFO or PubMed because it includes various multidisciplinary databases. The following search terms (and their derivatives) were entered: “Internet addict*”, “Internet gaming addiction”, “gaming addiction”, “Internet Gaming Disorder”, “compuls* Internet use”, “compuls* gam*”, “pathological Internet use”, “excessive internet use”, or “problematic Internet use”, and “clinic*”, “diagnos*”, “treat*, “therap*”, or “patient*”. Studies were selected based on the following inclusion criteria. Studies had to (1) contain quantitative empirical data; (2) have been published after 2000; (3) include clinical samples and/or clinical interventions for Internet and/or gaming addiction; (4) provide a full-text article (rather than a conference abstract); and (5) be published in English, German, Polish, Spanish, Portuguese, or French as the present authors speak these languages. The initial search yielded 152 results. Following a thorough inspection of the articles’ titles and abstracts, the articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. The search strategy is presented in Figure 1.

Additional articles were identified through searching the citations in the literature selected, resulting in the inclusion of another eight studies[20-27].

A total of 46 studies met the inclusion criteria. These studies are presented in Table 1. The included studies used clinical samples, and focused on characteristics of treatment seekers and online addiction treatment. Four main types of clinical research studies were identified, namely research involving (1) treatment seeker characteristics; (2) psychopharmacotherapy; (3) psychological therapy; and (4) combined treatment. The results section will outline each of these.

| Study | Aims | Sample and design | Treatment approach | Instruments | Results |

| Atmaca[28] | To describe a case of problematic Internet use successfully treated with an SSRI-antipsychotic combination | Case report | SSRI-antipsychotic combination: Citalopram 20 mg/d increased to 40 mg/d within 1 wk, continued for 6 wk; then quetiapine (50 mg/d) added and increased to 200 mg/d within 4 d | SCID-IV to assess Axis I psychiatric comorbidity[29] | Y-BOCS score decreased from 21 to 7 after treatment |

| n = 1 male 23-yr old single 4th year medical student | YBOCS[30,31] | Nonessential Internet use decreased from 27 to 7 h/wk; essential Internet use decreased from 4.5 to 3 h/wk | |||

| Improvement maintained at 4 mo follow-up with the same medication | |||||

| Bernardi et al[32] | To describe a clinical study of individuals with Internet addiction, comorbidities and dissociative symptoms | n = 50 adult outpatients self-referred for internet overuse in Italy (age M = 23.3, SD = 1.8 yr) | N/A | Youngs Internet Addiction Scale IAS[33] | Clinical diagnoses included 14% ADHD, 7% hypomania, 15% generalized anxiety disorder, 15% social anxiety disorder; 7% dysthymia, 7% obsessive compulsive personality disorder, 14% borderline personality disorder, and 7% avoidant personality disorder, 2% binge eating disorder |

| 9 women and 6 men scored ≥ 70 on Internet Addiction Scale; 19 with “possible Internet addiction” (scoring 40-69 on IAT) | Clinical interview | ||||

| DES[34] | |||||

| CGI[35] | |||||

| Sheehan Disability Scale[36] | |||||

| Structured Clinical Interviews for DSM-IV (SCID I and II)[37,38] | IAD associated with higher perception of family disability and higher Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Severity score | ||||

| Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression[39] | Scores for the Dissociative Experience Scale were higher than expected and related to higher obsessive compulsive scores, hours per week on the Internet, and perception of family disability | ||||

| Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety[40] | |||||

| Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale[41] | |||||

| YBOCS[30] | |||||

| CAARS:S[42] | |||||

| Beutel et al[43] | To present the assessment and clinical characterisation of individuals seeking help for computer and Internet addiction via a telephone hotline | N = 346 phone consultations (85.8% relatives, 14.2% persons affected) | Telephone consultations | Skala zum Computerspielverhalten [CSV-S (Scale for the Assessment of Pathological Computer Gaming)][44] | Consultation mainly sought by relatives (86% mothers) |

| 48% reported achievement failure and social isolation, lack of control (38%), family conflicts (33%) | |||||

| n = 131 patients (M = 21.9, SD = 6.6, range 13-47 yr, 96.2% male) | First diagnostic interview with expert clinicians | Symptom-Checklist SCL-90-R[45] | 96% of patients (n = 131) met criteria for pathological computer gaming | ||

| Specialised clinic for behavioural addictions in Germany | |||||

| Bipeta et al[46] | To compare control subjects with or without Internet addiction with patients with pure obsessive compulsive disorder with or without Internet addiction | n = 34 control subjects with or without Internet addiction (age M = 26.9, SD = 6.6 yr) | OCD patients treated for 1 year with standard pharmacological treatment for OCD (TAU), received clonazepam, tapered off in three weeks, and an SSRI or clomipramine | Youngs Diagnostic Questionnaire[47] | 11 OCD patients (28.95%) diagnosed with IA compared to 3 control subjects |

| n = 38 patients with obsessive compulsive disorder with or without Internet addiction (age M = 27.0, SD = 6.1 yr) | IA OCD group: 5 received 150-200 mg fluvoxamine/d, 4 received 150-200 mg sertraline/d, 1 received 60 mg fluoxetine/d, 1 received 200 mg clomipramine/d | IAT[48] | OCD group, no difference in OCD scores btw IA/OCD and non-IA/OCD groups | ||

| Non-IA OCD group: 8 received 150-300 mg fluvoxamine/d, 5 received 100-200 mg sertraline/d, 11 received 40-80 mg fluoxetine/d, 3 received 150-200 mg clomipramine/d | Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-IV (psychiatric interview)[12] | IA scores higher in IA/OCD group | |||

| BIS-11[49] | Treatment improved test scores | ||||

| YBOCS[30] | At 12 mo, 2/11 patients with OCD fulfilled IA criteria | ||||

| Claes et al[50] | To investigate the association among CB, CIU, and reactive/regulative temperament in patients with ED | n = 60 female patients with eating disorders in the Netherlands (38.3% with Anorexia nervosa, 6.7% with Anorexia binging-purging type, 26.7% with bulimia nervosa, and 28.3% with Eating Disorder not otherwise specified; age range 15-57 yr, mean age = 27.8, SD = 9.8 yr) | N/A | DSM-IV, standardised clinical interview[51] | Positive association btw CB and CIU, emotional lability, excitement seeking, lack of effortful control (lack of inhibitory and lack of activation control) |

| EDI-2[52,53] | 11.7% of CB patients with IA | ||||

| CBS[54] | No significant differences between ED subtypes regarding CIU | ||||

| Dutch Compulsive Internet Use Scale[55] | |||||

| BIS/BAS scales[56,57] | |||||

| DAPP[58,59] | |||||

| Adult Temperament Questionnaire-Short Form[60,61] | |||||

| Cruzado Díaz et al[62] | To describe clinical and epidemiological characteristics of inpatients in a clinical centre in Perú between 2001-2006 | n = 30 patients with “IA“ 90% devoted themselves to online games) in Perú | N/A | Reviewed 30 clinical registers through FEIA[63], a semi-structured instrument for psychiatric evaluation applied to clinical histories | Patient characteristics: |

| Young age (18.3 ± 3.8 yr old) | |||||

| All single males from 13 to 28 yr old (M = 18.3, SD = 3.8), 63.3% with secondary education completed and 66.7% dropped out | Patients completed a brief survey through an interview regarding information about their Internet use and online behaviours | Extensive daily Internet use (50% remained online for more than 6 h/d) | |||

| Descriptive, retrospective and transversal study | Primary Internet use: Online gaming (43.3% excessive gaming and 6.7% excessive gambling) | ||||

| Comorbidities (DSM-IV): High frequency of psychopathic behaviours (antisocial personality traits: 40%), 56.7% affective disorders (30% major depression and 26.7% dysthymia), 26.7% other addictions (13.3% gambling, 10% alcohol, 10% marihuana, 6.7% nicotine and 3.3% cocaine), 16.7% antisocial disorders (13.3% ADHD, social phobia 10% and 3.3% dysmorphic corporal disorder) | |||||

| DellOsso et al[20] | To assess the safety and efficacy of escitalopram in IC-IUD using a double-blind placebo-controlled trial | n = 19 adult subjects (12 men, mean age = 38.5, SD = 12.0 yr) with IC-IUD (as primary disorder) | Escitalopram started at 10 mg/d, increased and maintained at 20 mg/d for 10 wk | Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I[64] | Following double-blind phase, there were no significant differences in weekly non-essential Internet use and overall clinical response between treatment and placebo group |

| 19 wk prospective trial with 2 consecutive phases: 10 wk treatment phase (n = 17, 11 men, mean age = 37.5, SD = 12.0 yr = and 9 wk randomised double-blind placebo controlled trial (n = 14, 10 men, mean age = 40.0, SD = 11.5 yr) | Subsequently, participants randomly assigned to placebo or escitalopram for 9 wk | Time spent in non-essential Internet use (hours/wk) | |||

| CGI-I[35] | Side effects: Fatigue and sexual side effects in treatment, but not placebo group | ||||

| BIS[49] | |||||

| IC-IUD version of YBOCS[30] | |||||

| Du et al[65] | To evaluate the therapeutic effectiveness of group CBT for Internet addiction in adolescents | n = 56 adolescents with IA (age range 12-17 yr) | Group cognitive behavioural therapy: | Beards Diagnostic Questionnaire for Internet addiction[66] | Internet use decreased in both groups |

| n = 32 active treatment group (28 male, mean age = 15.4, SD = 1.7 yr) | Active treatment group: 8 1.5-2 h sessions of multimodal school-based group CBT with 6-10 students/group run by two child and adolescent psychiatrists (topics: Control, communication, Internet awareness, cessation techniques); group CB parent training; psychoeducation delivered to teachers | Internet Overuse Self-Rating Scale[67,68] | Only treatment group had improved time management skills and better emotional, cognitive and behavioural symptoms | ||

| Time Management Disposition Scale[69] | |||||

| Strength and Difficulties Questionnaire (Chinese edition)[70] | |||||

| n = 24 clinical control group (17 male, mean age = 16.6, SD = 1.2 yr) | Clinical control group: No intervention | SCARED[71] | |||

| Dufour et al[72] | To describe the sociodemographic characteristics of Internet addicts in a CDR, and to document their problems associated with other dependencies (alcohol, drugs, game practices), self-esteem, depression and anxiety | n = 57 Internet addiction treatment seekers (88.4% males, 11.6% females; age range = 18-62 yr (M = 30.5, SD = 11.8 yr). | N/A | IAT[48,73] | 88% of Internet addicts were male, with a mean age of 30, living with their parents with low income |

| Canada | Becks Anxiety inventory[74] | M = 65 h of Internet use per week: 57.8% MMORPGs, 35,1% video streaming, and 29.8% chat rooms | |||

| Becks Depression inventory[75] | Rosenberg test: 66.6% weak and very weak self-esteem; Depression in only 3.5% and anxiety in 7.5% | ||||

| DÉBA-Alcohol/Drugs/Gaming[76] | 45.6% received pharmacological treatment for mental disorders (psychotropic) and 33.3% had a chronic physical problem | ||||

| Self-esteem[77] | |||||

| Duven et al[78] | To investigate whether an enhanced motivational attention or tolerance effects are reported by patients with IGD | n = 27 male clinical sample from specialised behavioural addiction centre in Germany (n = 14 with IGD, n = 13 casual computer gamers) | N/A | AICA-S[44] | Attenuated P300 for patients with IGD in response to rewards relative to a control group |

| Semi-natural EEG designed with participants playing a computer game during the recording of event-related potentials to assess reward processing | SCL-90-R[45] | Prolonged N100 latency and increased N100 amplitude, suggesting tolerance during computer game play, and gaming reward attention uses more cognitive capacity in patients | |||

| Floros et al[79] | To assess the comorbidity of IAD with other mental disorders in a clinical sample | n = 50 clinical sample of college students presenting for treatment of IAD in Greece (39 males, mean age = 21.0, SD = 3.2 yr; 11 females, mean age = 22.6, SD = 4.5 yr) | N/A | OCS[80] | 25/50 presented with comorbidity of another Axis I disorder (10% with major depression, 5% with dysthymia and psychotic disorders, respectively), and 38% (19/50) with a concurrent Axis II personality disorder (22% with narcissistic, and 10% with borderline disorder) |

| DSQ[81] | |||||

| ZKPQ[82,83] | |||||

| SCL-90[84,85] | |||||

| Cross-sectional study | The majority of Axis I disorders (51.85%) were reported before IAD onset, 33.3% after onset | ||||

| Ge et al[86] | To investigate the association between P300 event-related potential and IAD | n = 41 IAD subjects (21 males, age M = 32.5, SD = 3.2 yr) | CBT | Standard auditory oddball task using American Nicolet BRAVO Instrument | IA individuals had longer P300 latencies, but similar P300 amplitudes compared to controls |

| n = 48 volunteers (25 males, age M = 31.3, SD = 10.5 yr) | Following treatment, P300 latencies decreased significantly, suggesting cognitive function deficits associated with IAD can be ameliorated with CBT | ||||

| Experimental task | |||||

| Han and Renshaw[21] | To test whether bupropion treatment reduces the severity of EOP and MDD | n = 50 male subjects with EOP and MDD (aged 13-45 yr) | Random allocation to either bupropion and EDU group or placebo and EDU group | Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV[64] | During active treatment period, Internet addiction, gaming, and depression decreased relative to placebo group |

| n = 25 treatment group (mean age = 21.2, SD = 8.0 yr, range = 13-42) | 12-wk treatment (8 wk active treatment phase and 4-wk post treatment follow-up period) | Youngs Internet Addiction Scale[87,88] | During follow-up, bupropion-associated reductions in gaming persisted, while depressive symptoms recurred | ||

| n = 25 placebo group (mean age = 19.1, SD = 6.2 yr, range = 13-39) | |||||

| Randomised controlled double-blind clinical trial | 150 mg/d Bupropion SR given and increased to 300 mg/d during first week | Becks Depression Inventory[89] | |||

| Han et al[24] | To test the effects of bupropion sustained release treatment on brain activity for Internet video game addicts | n = 11 IAG (IAG; mean age = 21.5, SD = 5.6 yr; mean craving score = 5.5, SD = 1.0; mean playing time = 6.5, SD = 2.5 h/d; mean YIAS score = 71.2, SD = 9.4) | Placebo group started with one pill and then raised to two pills | Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV[64] | Bupropion sustained release treatment works for IAG in a similar way as it works for patients with substance dependence |

| n = 8 HC (HC; mean age = 11.8, SD = 2.1 yr; mean craving score = 3.9, SD = 1.1; mean Internet use = 1.9, SD = 0.6 h/d; mean YIAS score = 27.1, SD = 5.3) in South Korea | Buproprion sustained release treatment: 6 wk | Beck Depression Inventory[89] | During exposure to game cues, IAG had more brain activation in left occipital lobe cuneus, left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, left parahippocampal gyrus relative to HC | ||

| Youngs Internet Addiction Scale[87] | |||||

| Experimental design | Participants underwent 6 wk of bupropion sustained release treatment (150 mg/d for first week, 300 mg/d afterwards) | Craving for Internet video game play: 7-point visual analogue scale | After treatment, craving, play time, cue-induced brain activity decreased in IAG | ||

| Brain activity measured at baseline and after treatment using 1.5 Tesla Espree fMRI scanner | |||||

| Han et al[22] | To assess the effect of methylphenidate on Internet video game play in children with ADHD | n = 62 children (52 males, mean age = 9.3, SD = 2.2 yr, range = 8.12), drug-naïve, diagnosed with ADHD, and Internet video game players in South Korea | Treatment with Concerta (OROS methylphenidate HCI, South Korea) | YIAS-K[87,88] | Following treatment, Internet addiction and Internet use decreased |

| Initial dosage: 18 mg/d, and maintenance dosage individually adjusted based on changes in clinical symptoms and weight | Korean DuPaul's ADHD Rating Scale[90,91] | ||||

| Changes in IA between baseline and treatment completion correlated with changes in ADHD, and omission errors from the Visual Continuous Performance Test | |||||

| Visual Continuous Performance Test using the Computerised Neurocognitive Function Test[92] | |||||

| Hwang et al[93] | To directly compare patients with IA to patients with AD regarding impulsiveness, anger expression, and mood | n = 30 patients with IA (mean age = 22.7, SD = 6.7 yr) | N/A | Korean version of Youngs IAT[48,94] | IA and AD groups showed lower agreeableness and higher neuroticism, impulsivity, and anger expression compared to the HC group (all related to aggression) |

| n = 30 patients with AD (mean age = 30.0, SD = 5.9 yr) | SCID[64] | Addiction groups had lower extraversion, openness to experience, and conscientiousness, were more depressive and anxious than HCs | |||

| n = 30 HCs (HCs, mean age = 25.3, SD = 2.8 yr) | Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test-Korean version[95] | Severity of IA and AD positively correlated with these symptoms | |||

| Outpatient clinic in South Korea | Korean version of the NEO-PI-R[96,97] | ||||

| Korean version of the BIS-11[98,99] | |||||

| Korean version of the STAXI-K[100,101] | |||||

| Kim[23] | To examine the effect of a reality therapy (R/T) group counselling programme for Internet addiction and self-esteem | n = 25 university students in South Korea (20 males, mean age = 24.2 yr) | Treatment group (n = 13, 10 males): Participated in R/T group counselling programme, 2 60-90 min sessions/wk for 5 consecutive weeks (with the purpose of taking control and changing thinking and behaviours) | K-IAS[102] | Treatment programme reduced addiction level and increased self-esteem |

| CSEI[103] | |||||

| Randomised controlled trial/quasi- experimental design | |||||

| Control group (n = 12, 10 males): No treatment | |||||

| Kim et al[25] | To evaluate the efficacy of CBT combined with bupropion for treating POGP in adolescents with MDD | n = 65 adolescents with MDD and POGP in South Korea (aged 13-18 yr) | n = 32 CBT group (medication and CBT): 8 wk intervention; 159 mg bupropion/d for 1 wk, then 300 mg/d for 7 wk; participated in 8 session weekly group CBT; weekly 10 min interviews | BDI[89] | Internet addiction decreased and life satisfaction increased in CBT and medication group relative to medication only group, but no changes in depression |

| BAI[74] | |||||

| YIAS[87,88] | |||||

| Modified-School Problematic Behaviour Scale[104] | Anxiety increased in medicated group | ||||

| Prospective trial | n = 33 clinical control group (medication only, as above) | Modified Students Life Satisfaction scale[105] | |||

| Kim et al[106] | To investigate the value of Youngs IAT for subjects diagnosed with Internet addiction | n = 52 individuals presenting with Internet addiction at university hospital in South Korea (47 males; mean age = 21.7, SD = 7.1 yr, range: 11-38) | N/A | Clinical interview | Samples mean IAT score below cut-off (70) |

| Youngs IAT[107,108] | |||||

| Classification of IA severity via DSM-IV-TR[12] | IAT detected only 42% of sample as having Internet addiction | ||||

| No significant differences in IAT scores between mild, moderate and severe Internet addition found | |||||

| No association between IAT scores and Internet addiction duration of illness found | |||||

| IAT has limited clinical utility for evaluating IA severity | |||||

| Kim et al[109] | To compare patients with IGD with patients with AUD and HC regarding resting-state ReHo | n = 45 males seeking treatment in South Korea | N/A | Youngs IAT[87] | Significantly increased ReHo in PCC of the IGD and AUD groups |

| n = 16 IGD patients (mean age = 21.6, SD = 5.9 yr) | SCID[64] | Decreased ReHo in right STG of IGD, compared with AUD and HC groups | |||

| n = 14 AUD patients (mean age = 28.6, SD = 5.9 yr) | AUDIT-K[110] | Decreased ReHo in anterior cingulate cortex of AUD patients | |||

| n = 15 HCs (mean age = 25.4, SD = 5.9 yr) | BDI[89] | Internet addiction severity positively correlated with ReHo in medial frontal cortex, precuneus/PCC, and left ITC in IGD | |||

| BAI[74] | Impulsivity negatively correlated with ReHo in left ITC in IGD | ||||

| BIS-11[111] | Increased ReHo in PCC: Neurobiological feature of IGD and AUD | ||||

| FMRI resting data acquired via Philips Achieva 3-T MRI scanner using standard whole-head coil, obtaining 180 T2 weighted EPI volumes in each of 35 axial planes parallel to anterior and posterior commissures | Reduced ReHo in STG: Neurobiological marker for IGD specifically relative to AUD and HCs | ||||

| King et al[112] | To present a case study of an individual with GPIU | n = 1, 16-yr old male in Australia | N/A | N/A | PIU identified due to: (1) use of several different Internet functions; (2) social isolation; (3) procrastination and time-wasting tendencies |

| Case study | Problems unlikely to have occurred without the Internet | ||||

| Ko et al[113] | To evaluate the diagnostic validity of IGD criteria, and to determine the cut-off point for IGD in DSM-5 | n = 225 adults in Taiwan (n = 75 individuals with IGD (63 males, mean age = 23.4, SD = 2.6 yr), no IGD (63 males, mean age = 22.9, SD = 2.5 yr), and IGD in remission (63 males, mean age = 23.8, SD = 2.9 yr), respectively) | N/A | Diagnostic interview based on DSM-5 IGD criteria[7] | Diagnostic accuracy of DSM-5 IGD items between 77.3% and 94.7% (except for deceiving and escape), and differentiated IGD from remitted individuals |

| DC-IA-C[114] | Meeting ≥ 5 IGD criteria: Best cut-off point to differentiate IGD from non-IGD and remitted individuals | ||||

| Chinese version of the MINI[115] | |||||

| QGU-B[116] | |||||

| CIAS[117] | |||||

| Liberatore et al[118] | To describe the prevalence of IA in a clinical sample of Latino adolescents receiving ambulatory psychiatric treatment | n = 71 adolescent patients in Puerto Rico (39 males, aged 13-17 yr), 39.4% diagnosed with disruptive disorder, 31.0% with mood disorder, 19.7% with mood and disruptive disorder | N/A | Spanish version of the Internet Addiction Test (IAT)[87] | Sample did not involve any cases of severe IA |

| 71.8% of the sample had no IA problem | |||||

| 11.6% discussed Internet use with therapists | |||||

| IA correlated with mood disorders | |||||

| Liu et al[119] | To test the effectiveness and underlying MFGT | n = 92 (46 adolescents with 12-18 yr old, and 46 parents, aged 35-46 yr old) | MFGT is a new approach to treat Internet addiction (IA) behaviours that has not been tested before | Structured questionnaires at pre-test (T1), post-test (T2) and follow-up (T3): | Significantly decreased IA in EG at T2 and maintained in T3 (adolescents IA rate dropped from 100% at baseline to 4.8% after intervention, then remained at 11.1%) |

| 2 groups: 1 experimental (EG; MFGT adolescents and parents) and 1 control (CG; waiting-list similar adolescents and parents) | MFGT = group therapy for families, both adults and adolescents that have the same problem (IA) | Adolescents scales: | |||

| Significantly better reports in the EG from adolescents and parents compared with those in the CG | |||||

| Adolescent Pathological Internet Use Scale APIUS[120] | Underlying mechanism of less IA was partially explained by adolescent satisfaction of their psychological needs and improved parent-adolescent communication and closeness | ||||

| EG: Adolescents: 17 males and 4 females (age: M = 15, SD = 1.73); | Advantage: Peer group (support and learn from peer confrontation) | Parents scales: | |||

| Parents: 5 males and 16 females (age: M = 40.9, SD = 2.85) | Transference reactions occur within and between families | Closeness to Parents[121] | |||

| CG: Adolescents: 21 males and 4 females (age: M = 15.7, SD = 1.2); Parents: Idem to EG (no sign. Diff). | Parent-Adolescent Communication Scale[122] | ||||

| China | College Students Psychological Needs and Fulfillment Scale[123] | ||||

| Quasi-experimental design | |||||

| Müller et al[124] | To characterize German treatment seekers and to determine the diagnostic accuracy of a self-report scale for | n = 290 mostly male (93.8%) treatment seekers between 18 and 64 yr (M = 26.4, SD = 8.22) | Treatment of behavioural addictions | SCL-90R[125] | 71% met clinical IA diagnosis |

| PHQ[126] | Displayed higher levels of psychopathology, especially depressive and dissociative symptoms | ||||

| IA | Germany | Non-experimental design | GAD-7[127] | Half met criteria for one further psychiatric disorder, especially depression | |

| CDS-2[128] | Level of functioning decreased in all domains | ||||

| AICA-S showed | |||||

| AICA-S[129] | good psychometric properties and satisfying diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity: 80.5%; specificity: 82.4%) | ||||

| Müller et al[130] | To compare personality profiles of a sample of patients in different rehabilitation centres | IA group: 70 male patients with an addiction disorder that additionally met the criteria for IA; M =29.3 yr (SD = 10.66; range 16-64) | N/A | Computer game | Patients with comorbid IA can be discriminated from other patients by higher neuroticism and lower extraversion and lower conscientiousness |

| Non-experimental design | Addiction (AICA-S)[129] | ||||

| AD group: 48 male patients suffering from AD; M = 31.7 yr; SD = 9.18; range 17-65) | NEO-FFI[131] | After controlling for depressive symptoms, lower conscientiousness turned out to be a disorder-specific risk factor | |||

| Germany | BDI-II[132] | ||||

| Müller et al[133] | To evaluate the relationships between personality traits and IGD | n = 404 males aged 16 yr and above | N/A | AICA-S[44] | IGD associated with higher neuroticism, decreased conscientiousness and low extraversion |

| 4 groups: | Experimental design: Characteristics of people selected for assigning them to two groups, non-random allocation | The comparisons to pathological gamblers indicate that low conscientiousness and low extraversion in particular are characteristics of IGD | |||

| IGD group: 115 patients with IGD | AICA-C[134] | Etiopathological model proposed for addictive online gaming | |||

| Clinical CG: 74 controls seeking treatment for IGD, but not diagnosable | Berlin Inventory for Gambling[135] | ||||

| Gambling group: 115 gambling patients | NEO Five-Factor Inventory[131] | ||||

| Healthy CG: 93 individuals with regular or intense use of online games | |||||

| Germany | |||||

| Park et al[136] | To examine the effectiveness of treating an Internet-addicted young adult suffering from interpersonal problems based on the MRI interactional model and Murray Bowen's family systems theory | 1 family case study consisting of husband (age 50), wife (age 50), 2 sons (ages 22, 23), older son with Internet addiction and interpersonal problems | Comparative analysis method | Characteristics of the parents family of origin and dysfunctional communication pattern associated with interpersonal problems revealed by participants | |

| South Korea | Miles and Huberman's matrix and network[137] | Both the MRI model and Bowen's family systems theory produced effective treatments | |||

| Poddar et al[138] | To describe a pilot intervention using MET and CBT principles to treat IGD in an adolescent | n = 1 | Initial therapy session: Rapport building with patient, detailed interview, primary case formulation | IQ ESDST, | IGD due to child neglect and boredom, consolidated by subsequent negative reinforcements |

| 14-yr-old boy | Subsequent sessions: Psychoeducation, cost/benefit analysis of behaviour (motivation level improved) | BVMGT, and TAT | |||

| India | Progressive muscle relaxation because gaming urge accompanied by physiological/emotional arousal | IAT | Individual interventions encouraged as there are varied antecedents and consequences for IGD development | ||

| Case study | MET-CBT principles for IGD resulted in improvement | ||||

| Subsequently: Game addiction assessment, contract for behaviour modification (reduce gaming time, increase other activities) | Therapy terminated when gains had consolidated | ||||

| Tokens introduced as positive reinforcement | Good exam scores achieved | ||||

| Less time spent gaming on weekdays, but excess on weekends | Weekend gaming times reduced | ||||

| Patient recorded Thoughts, | IAT score reduced to 48 (from 83) | ||||

| Emotions and Behaviors (TE and B) contributing to gaming (result: Gaming due to boredom) | |||||

| Non-gaming behaviour reinforced via scooty rides | |||||

| Santos et al[139] | To describe a treatment of a patient with PD, OCD (both anxiety disorders) and IA involving pharmacotherapy and CBT and test its efficacy | Case report | Pharmacotherapy and CBT | Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAMA-A)[40] | Treatment effective for anxiety and IA |

| n = 1 | CBT 1x/week for 10 wk | Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D)[39] | |||

| 24-yr-old Caucasian woman | Pharmacotherapy [clonazepam (0.5 mg) and sertraline (50 mg) once daily] | Chambless BSQ[140] | |||

| A patient with PD, OCD and IA | Both (pharmaco and CBT) started together | Bandelow PA[141] | |||

| Brazil | CBT focus: Teach patient how to deal with anxiety and internet use (i.e., breathing retraining with diaphragmatic breathing exercise, education about PD and OCD symptoms and internet use, time management, identifying PIU triggers, changing habits, cognitive restructuring, exposure and response prevention, social support promotion, building alternative activities, functional internet use promotion) | IAT | |||

| CGI[142] | |||||

| Senormanci et al[143] | To investigate the attachment styles and family functioning of patients with IA | n = 60 | N/A | IAT[48] | Patients with IA had higher BDI and higher attachment anxiety sub-scores on the ECR-r compared with those in the CG |

| 2 groups: | BDI[89] | ||||

| EG: 30 male patients with IA [age: M = 21.6 (18-20) yr] | Experiences in Close Relationships Questionnaire-r [144] | IA patients evaluated their family functioning as more negative and reported problems in every aspect addressed by the FAD | |||

| CG: 30 healthy males without IA | |||||

| Non-experimental | Family Assessment Device[145] | Scores on the FAD behaviour control, affective responsiveness, and problem-solving subscales (and on the FAD communication, roles, and general functioning subscales) significantly higher in patients compared with CG | |||

| Senormanci et al[146] | To determine the predictor effect of depression, loneliness, anger and interpersonal relationship styles for IA in patients diagnosed with IA | n = 40 male IA patients with at least 18-yr-old | N/A | IAT[48] | Duration of Internet use (hours/day) and STAXI anger in subscale predicted IA. Although the duration is not adequate for IA diagnosis, it predicts IA |

| Turkey | BDI[89] | It is helpful for clinicians to regulate the hours of Internet use for patients with excessive or uncontrolled internet use | |||

| STAXI[100] | |||||

| UCLA Loneliness Scale[147] | |||||

| IRSQ, subscale “Contributing and inhibiting styles”[148] | Psychiatric treatments for expressing anger and therapies focussing on emotion validation may be useful | ||||

| Shek et al[149] | To described an indigenous multi-level counselling programme designed for young people with IA problems based on the responses of clients | n = 59 | Indigenous multilevel counselling program designed to provide services for young people with Internet addictive behaviour in Hong Kong: | 3 versions of IA Young's assessment tools[150]: 10-item, 8-item and 7-item measures[151-153] | The outcome evaluation, pretest and posttest data showed IA problems decreased after joining programme |

| 58 male and 1 female | (1) Emphasis on controlled and healthy use of the Internet; (2) Understanding the change process in adolescents with Internet addiction behaviour; (3) Utilization of motivational interviewing model; (4) Adoption of a family perspective; (5) Multi-level counselling model; (6) Utilization of case work and group work | Goldberg's framework[154] | |||

| Most in early adolescence (aged 11-15 yr; n = 29) and late adolescence (aged 16-18 yr; n = 27), while 3 were over 18 | Chinese Internet Addiction Scale (CIA-Goldberg) | Slight positive changes in parenting attributes | |||

| China | Items for assessing beliefs and behaviours for using Internet: 7 items from Computer Use Survey[155] | Participants subjectively perceived the programme was helpful | |||

| 6 items from OCS[80] | |||||

| 6 items from Internet Addiction-Related Perceptions and Attitudes Seale[156] | |||||

| 2 items from IAD-Related Experience Scale[157] | |||||

| 33-item C-FAI developed[158] | |||||

| Chinese Purpose in Life Questionnaire[159] | |||||

| Chinese Beck Depression Inventory[160] | |||||

| Chinese Hopelessness Seale[161] | |||||

| Chinese Rosenberg Self-Esteem Seale[162] | |||||

| Tao et al[163] | To develop diagnostic criteria for IAD and to evaluate the validity of proposed diagnostic criteria for discriminating non-dependent from dependent Internet use in the general population | 3 stages: Criteria development and item testing; criterion-related validity testing; global clinical impression and criteria evaluation; | N/A | N/A: Authors developed the proposed Internet addiction diagnostic criteria, which have been one of the main sources for the APAs IGD criteria | Proposed Internet addiction diagnostic criteria: Symptom criterion (7 clinical IAD symptoms ), clinically significant impairment criterion (functional and psychosocial impairments), course criterion (duration of addiction lasting at least 3 mo, with at least 6 h of non-essential Internet use per day) and exclusion criterion (dependency attributed to psychotic disorders) |

| Stage 1: n = 110 patients with IA in SG, M = 17.9 SD = 2.9 yr (range: 12-30 yr), 91.8% (n = 101) males; 408 patients in IA in TG, M = 17.6, SD = 2.7 yr (range: 12-27 yr), 92.6% (n = 378) male; Stage 2: n = 405; Stage 3: n = 150 (M = 17.7, SD = 2.8, (92.7% males) | Diagnostic score of 2 + 1, where first 2 symptoms (preoccupation and withdrawal symptoms) and min. 1/5 other symptoms (tolerance, lack of control, continued excessive use despite knowledge of negative effects/affects, loss of interests excluding Internet, and Internet use to escape or relieve a dysphoric mood) was established | ||||

| China | Inter-rater reliability: 98% | ||||

| Te Wildt et al[164] | To examine the question whether the dependent use of the Internet can be understood as an impulse control disorder, an addiction or as a symptom of other psychiatric conditions | EG: n = 25 patients (76% male, M = 29.36 yr, SD = 10.76) | 2 groups matched: The EG and CG | Preliminary telephone interview to test inclusion criteria with Young's and Beard's IA criteria[48,66] | Compared to controls, patient group presented significantly higher levels of depression (BDI), impulsivity (BIS) and dissociation (DES) |

| CG: Matched for age (M = 29.48; SD = 9.56), sex (76% males) and school education, and similar level of intelligence | Non-experimental design | Statistical Clinical Interview for DSM-IV[64] | PIU shares common psychopathological features and comorbidities with substance-related disorders | ||

| German Internet Addiction Scale ISS[165] | |||||

| German version of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale BIS[49] | Should be viewed as diagnostic entity in itself within a spectrum of behavioural and substance dependencies | ||||

| Derogatis Symptom Checklist (SCL-90-R)[166,167] | |||||

| BDI[89,168] | |||||

| DES[169,170] | |||||

| SOC[171,172] | |||||

| IIP-D[173,174] | |||||

| Tonioni et al[26] | To test whether patients with IA present different psychological symptoms, temperamental traits, coping strategies and relational patterns relative to patients with PG | Two clinical groups: | N/A | IAT[48] | IA and PG had higher scores than control group on depression, anxiety and global functioning |

| 31 IA patients (30 males) and 11 PG patients (10 males) and a control group (38 healthy subjects; 36 males) matched with the clinical groups for gender and age were enrolled | Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale[40] | IA patients had higher mental and behavioural disengagement associated with an important interpersonal impairment relative to PG patients | |||

| Hamilton Depression Scale[39] | IA and PG groups used impulsive coping, and had socio-emotional impairment | ||||

| Global Assessment of Functioning[112] | |||||

| Snaith-Hamilton Pleasure Scale[175] | |||||

| Temperament and Character Inventory-Revised[176] | |||||

| Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced[177] | |||||

| Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment[178] | |||||

| Tonioni et al[27] | To investigate psychopathological symptoms, behaviours and hours spent online in patients with IAD | n = 86: 21 clinical patients in hospital-based psychiatric IAD service (mean age=24, SD = 11 yr); 65 control subjects | N/A | Internet addiction interview[47] | IAD patients had significantly higher scores on IAT relative to controls |

| IAT[179] | Only item 7 (how often do you check your e-mail before something else that you need to do?) showed a significant inverse trend | ||||

| Symptom Checklist-90-Revised[125] | SCL-90-R anxiety and depression scores and IAT item 19 (How often do you choose to spend more time online over going out with others?) positively correlated with weekly online hours in IAD patients | ||||

| van Rooij et al[180] | To evaluate the pilot treatment for IA created for the Dutch care organization (to explore the possibility of using an existing CBT and MI based treatment programme (lifestyle training) from therapists experiences with 12 Internet addicts | n = 12 Internet addicts and n = 5 therapists treating them | Treatment: A manual-based CBT | Data sources: (1) Session Reports; (2) Case Review Meeting Minutes; (3) Questionnaires: | Therapists report programme (originally used for substance dependence and pathological gambling) fits problem of Internet addiction well |

| The Netherlands | Standard Lifestyle Training programme, a manual-based treatment programme[181,182] | Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS)[55] | Interventions focused on controlling and reducing Internet use, and involved expanding (real life) social contacts, regaining proper daily structure, constructive use of free time, and reframing beliefs | ||

| Therapy combines CBT and MI[183,184] | Brief Situational Confidence questionnaire[187] | Therapist report: Treatment achieved progress for all 12 treated patients | |||

| Focuses on eliciting and strengthening motivation to change, choosing a treatment goal, gaining self-control, relapse prevention, and coping skills training[185,186] | Patient report: Satisfaction with treatment and behavioural improvements | ||||

| 10 outpatient sessions of 45 min each, with 7 of these taking place within a period of 10 wk, the remaining 3 within a period of 3 mo | |||||

| Each session: Introduction, evaluation of current status, discussing homework, explaining theme of the day, practicing a skill, receiving homework, and finally closing the session | |||||

| Wölfling et al[188] | To investigate whether IA is an issue in patients in addiction treatment | n = 1826 clients in impatient centres | N/A | Internet and Computer Game Addiction (AICA-S)[189,190] | Comorbid IA associated with higher levels of psychosocial symptoms, especially depression, obsessive-compulsive symptoms, and interpersonal sensitivity |

| Male patients meeting criteria for comorbid IA (EG; n = 71) compared with a matched control group of male patients treated for alcohol addiction without addictive Internet use (CG; n = 58) | Symptom Checklist 90R (SCL-90-R)[191] | ||||

| PHQ[126] | IA patients meet criteria for additional mental disorders more frequently and display higher rates of psychiatric symptoms, especially depression, and might be in need of additional therapeutic treatment | ||||

| GAD-7[127] | |||||

| Germany | |||||

| Wölfling et al[192] | To test the effects of a standardized CBT programme for IA | n = 42 patients with IA, all male from 16-yr-old (M = 26.1, SD = 6.60, range: 18-47) | Short-Term outpatient Treatment for Internet and Computer Game | Inclusion criteria: | 70.3% of patients completed therapy |

| Addiction STICA (127) based on CBT techniques known from treatment programmes of other forms of addictive behaviour, consisting of 15 group sessions and additional 8 individual therapy sessions | AICA-S[193,194] | After treatment, symptoms of IA decreased significantly | |||

| Standardized clinical interview of IA (AICA-C; Checklist for the Assessment of Internet and Computer Game Addiction)[132] | Psychopathological symptoms and associated psychosocial problems decreased | ||||

| Individual sessions dealt with individual contents; group sessions followed clear thematic structure: First third of programme: Main themes about development of individual therapy aims, identification of Internet application associated with symptoms of IA, conducting holistic diagnostic investigation of psychopathological symptoms, deficits, resources, and comorbid disorders | GSE[195] | ||||

| NEO Five-Factor Inventory[131] | |||||

| Symptom Checklist 90R[196] | |||||

| Motivational techniques applied to enhance patients intention to cut down dysfunctional behaviour | |||||

| Second third: Psychoeducation elements; deepened Internet use behaviour analysis (focusing on triggers and patient reactions on cognitive, emotional, psychophysiological, and behavioural levels in that situation (SORKC scheme)[193] for development of a personalized model of IA for each patient based on interaction between online application, predisposing and maintaining factors of the patient (e.g., personality traits) and the patients social environment | |||||

| Last stage: Situations with heightened craving for getting online further specified and strategies to prevent relapse developed | |||||

| Wölfling et al[197] | To investigate the occurrence of BSD in patients with excessive Internet use and IA | n = 368 treatment seekers with excessive to addictive Internet use screened for bipolar spectrum disorders | N/A | AICA-S[194] | Comorbid BSD more frequent in patients meeting criteria for IA (30.9%) than among excessive users (5.6%) |

| Germany | BSD assessed using MDQ[198] | This subgroup showed heightened psychopathological symptoms, including substance use disorders, affective disorders and personality disorders | |||

| SCL-90R[199,200] | |||||

| Further differences were found regarding frequency of Internet use regarding social networking sites and online-pornography in patients with BSD who engage more frequently | |||||

| Patients with IA have heightened probability for meeting BSD criteria | |||||

| Recommendation: Implement BSD screening in patients presenting with IA | |||||

| Young[201] | To investigate the efficacy of using CBT with Internet addicts | n = 114 Internet addicts in treatment (42% women (mean age = 38; men mean age = 46) | Sessions conducted between client and principle investigator | IAT[48] | Preliminary analyses indicated most clients managed their presenting complaints by the eighth session |

| Initial sessions gathered familial background, nature of presenting problem, its onset and severity | Self-devised Client Outcome Questionnaire administered after 3rd, 8th, and 12th online session, and at 6 mo follow-up: | Symptom management sustained at 6-mo follow-up | |||

| CBT utilized to address presenting symptoms related to computer use, specifically abstinence from problematic online applications and strategies to control online use | 12 items regarding clients behaviour patterns and treatment successes during counselling process; questions rated how effective counselling was at helping clients achieve targeted treatment goals associated with Internet addiction recovery; questions assessed motivation to quit Internet abuse, ability to control online use, engagement in offline activities, improved relationship functioning, and improved offline sexual functioning (if applicable) | ||||

| Counselling also focused on behavioural issues or other underlying factors contributing to online abuse, such as marital discord, job burnout, problems with co-workers, and academic troubles, depending on respective client | |||||

| Young[202] | To test a specialized form of CBT, CBT-IA | n = 128 clients to measure treatment outcomes using CBT-IA (65% male; age range: 22-56 yr) | CBT-IA: 3-phase approach including behaviour modification to control compulsive Internet use, cognitive restructuring to identify, challenge, and modify cognitive distortions that lead to addictive use, and harm reduction techniques to address and treat co-morbid issues associated with the disorder | IAT[48] | Over 95% of clients managed symptoms at the end of the 12 wk period |

| 78% sustained recovery six months following treatment | |||||

| Administered in 12 weekly sessions | CBT-IA ameliorated IA symptoms after 12 weekly sessions and consistently over 1, 3 and 6 mo after therapy | ||||

| Sessions conducted between client and principle investigator | |||||

| Initial sessions gathered familial background, | |||||

| symptoms of the presenting problem, its onset, and severity | |||||

| CBT-IA addressed presenting symptoms related to computer use, specifically abstinence from problematic online applications and strategies to control use | |||||

| CBT-IA also focused on cognitive issues and harm reduction for underlying factors contributing to Internet abuse such as marital discord, job burnout, problems with co-workers, or academic troubles, depending on respective client | |||||

| Internet use routinely evaluated and treatment outcomes evaluated after 12 sessions and at 1, 3 and 6 mo follow-up | |||||

| Yung et al[203] | To improve IAD involving Google Glass through residential treatment for alcohol use disorder | n = 1 (31-yr-old man who exhibited problematic use of Google Glass) | Navys SARP | N/A regarding SARP and measures, only about his reactions (e.g., withdrawal, craving, etc.) | Following treatment, reduction in irritability, movements to temple to turn on device, and improvements in short-term memory and clarity of thought processes |

| Case report | All electronic devices and mobile computing devices customarily removed from patient during substance rehabilitation treatment | ||||

| United States | 35-d residential treatment | Patient continued to intermittently experience dreams as if looking through the device | |||

| Zhou et al[204] | To examine whether Internet addicted individuals share impulsivity and executive dysfunction with alcohol-dependent individuals | n = 66 | N/A | BIS-11 | Impulsiveness scores, false alarm rate, total response errors, perseverative errors, failure to maintain set of IAD and AD group significantly higher than that of NC group |

| 22 IAD, 22 patients with AD, and 22 NC (NC consisting of citizens living in the city) | Go/no-go task | ||||

| Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (Beijing Ka Yip Wise Development Co., Ltd, computerized version VI) | Hit rate, percentage of conceptual level responses, number of categories completed, forward scores, backwards scores of IAD and AD group significantly lower than that of NC group | ||||

| China | Digit span task | ||||

| Experimental design | Modified Diagnostic Questionnaire for Internet Addiction (YDQ)[66] | No differences in above variables between IAD group and AD group | |||

| Structured clinical interview (Chinese version) | Internet addicted individuals share impulsivity and executive dysfunction with alcohol-dependent patients | ||||

| SADQ[205] | |||||

| Hamilton Depression Scale[206] | |||||

| Barratts Impulsivity Scale (BIS-11)[49] | |||||

| Zhu et al[207] | To observe the effects of CT with EA in combination with PI on cognitive function and ERP, P300 and MMN in patients with IA | n = 120 patients in China with IA randomly divided into 3 groups: | Overall treatment period = 40 d | Internet Addiction Test[208] | Following treatment, IA decreased in all groups |

| n = 39 EA group (n = 40, 27 male, mean age = 22.5, SD = 2.1 yr) | EA applied at acupoints Baihui (GV20), Sishencong (EX-HN1), Hegu (LI4), Neiguan (PC6), Taichong (LR3), Sanyinjiao (SP6) and retained for 30 min once every other day | Wechsler Memory Scale (WMS)[209] | Decrease stronger in CT group relative to both other groups | ||

| n = 36 PI group (n = 25 male, mean age = 21.0, SD = 2.0 yr) | PI with cognitive-behaviour mode every 4 d | ERP observation[210] using MEB 9200-evoked detector | P300 latency depressed and amplitude raised n EA group | ||

| n = 37 CT group (n = 40, 27 males, mean age = 22.5, SD = 2.3 yr) | EA and PI used in CT group | Latency and amplitude of MMN and P300 recorded via EEG | MMN amplitude increased in CT group | ||

| Short-term memory capacity and short-term memory span improved | |||||

| EA and PI improves cognitive function in IA via acceleration of stimuli discrimination and information processing on brain level |

A total of 25 studies[19,26,27,32,43,50,62,72,78,79,93,106,109,111,112,118,124,130,133,143,146,163,164,188,204] investigated the characteristics of treatment seekers. Here, treatment seekers are defined as individuals seeking professional support for online addiction-related problems. The following paragraphs will outline the treatment seekers’ sociodemographic characteristics, Internet/gaming addiction measures used to ascertain diagnostic status in the respective studies, differential diagnoses and comorbidities.

In the included studies, sample sizes ranged from a case study of a male in Australia presenting with the problem of generalised pathological Internet use[112] to a total of 1826 clients sampled from 15 inpatient alcohol addiction rehabilitation centres in Germany, of which 71 also presented with Internet addiction and were then compared to a control group of 58 patients treated for alcohol addiction only[188]. Ages ranged from 16 years[112] to a mean age of 30.5 years[72]. The majority of studies used male participants, with one study using female participants only[50]. Most studies included individuals seeking treatment for Internet addiction and/or problematic Internet use in specialised inpatient and outpatient treatment centres. A number of studies included particular samples, such as individuals sampled via phone consultations (i.e., including 86% relatives of the affected individuals)[43], patients sampled in alcohol rehabilitation centres[130], patients diagnosed with obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD)[46], and female patients treated for eating disorders[50].

Treatment seekers were sampled from various continents. Within Europe, samples included treatment seekers in Germany[43,78,124,130,133,164,188,197], The Netherlands[50], Italy[26,27,32], and Greece[79]. In North America, a Canadian sample was included[72]. In South America, samples included individuals from Perú[62], Puerto Rico[118], and Brazil[139]. In Western Asia, Turkish individuals were sampled in two studies[143,146], whereas in East Asia, participants were from China[163,204], South Korea[93,106,109], and Taiwan[113]. One case study included an Australian adolescent[112].

Internet and/or gaming addiction were measured with a number of different psychometric tools in the included studies, sometimes combined with structured clinical interviews. Clinical interviews were explicitly mentioned in the reports of eight studies[32,50,62,93,106,109,164,204], and these consisted mostly of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV[64], a semi-structured interview for DSM-IV Axis I diagnoses for mental disorders.

In terms of psychometric measures, in the majority of studies, Young’s popular Internet Addiction Test[48], the IAT, was used[26,32,72,93,106,109,118,143,146]. The IAT is a 20-item self-report scale that measures the extent of Internet addiction based on criteria for substance dependence and pathological gambling[51], and includes loss of control, neglecting everyday life, relationships and alternative recreational activities, behavioural and cognitive salience, negative consequences, escapism/mood modification, and deception. Significant problems due to Internet use are identified if individuals score between 70-100 on the test, and frequent problems when they score between 40-69[48]. However, previous research has suggested that across studies, different cut-off scores for the IAT have been used to classify individuals[6], impairing comparisons across studies.

Another popular measure appeared to be the Assessment of Internet and Computer Game Addiction Scale (AICA-S)[44,194], which was used in seven studies[43,78,124,130,133,188,197]. The AICA-S is a 16-item scale and includes questions about the frequency of specific Internet usage, associated negative consequences and the extent to which use is pathological from a diagnostic point of view. Fourteen out of the total sixteen main questions are used to calculate a clinical score, and to distinguish normal from potentially addictive use[211].

Other measures included the Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS)[55], a 14-item unidimensional self-report questionnaire including loss of control, preoccupation (cognitive and behavioural), withdrawal symptoms, coping/mood modification, and conflict (inter- and intrapersonal). The CIUS classification is based on the DSM-IV TR diagnoses for substance dependence and pathological gambling[12], and was used in one study[50]. Moreover, in one study[79], the Online Cognitions Scale was used[80], which is a 36-item questionnaire that measures cognitions related to problematic Internet use, and includes subscales on loneliness/depression, diminished impulse control, social comfort, and distraction. In another study[113], Chen’s Internet Addiction Scale[117] was administered, which is a 26-item self-report measure of core Internet addiction symptoms, including tolerance, compulsive use, withdrawal, and related problems (i.e., negative impact on social activities, interpersonal relationships, physical condition, and time management). Another study[164] used the Internet Addiction Scale[212], as well as a combination of Young’s[213] and Beard’s[66] Internet addiction criteria, including preoccupation, tolerance, loss of control, withdrawal, overall impairment, deception, and escapism[164]. The latter was also used in another study[204].

A different approach was taken by Tao et al[163], who intended to develop diagnostic criteria for Internet Addiction Disorder (IAD) and to evaluate the validity of these criteria. Accordingly, in order to be diagnosed with IAD, patients had to fulfil the following criteria: The presence of preoccupation and withdrawal (combined with at least one of the following: Tolerance, lack of control, continued excessive use despite knowledge of negative effects/affects, loss of interests excluding the Internet, and Internet use to escape or relieve a dysphoric mood). In addition to this, clinically significant impairment had to be identified (i.e., functional and psychosocial impairment), and the problematic behaviour had to last a minimum of three months, with at least six hours of non-essential Internet use a day. This study has been used as a basis for the APA’s research classification of Internet Gaming Disorder in the DSM-5.

As this section demonstrates, a wide variety of measurements have been applied in order to ascertain Internet or Internet-use related addiction, sometimes involving an expert assessment by an experienced professional. As has been stated in previous research[6], no gold standard exists to measure Internet addiction with high sensitivity and specificity, which is exacerbated by the use of different cut-off points on the same measures across studies. To mitigate this diagnostic conundrum, a diagnosis of Internet addiction would significantly benefit from including a structured clinical interview administered by a trained professional[214], and this would help eliminating false positives and false negatives in the context of diagnosis.

A number of studies investigated differential diagnoses and/or comorbidity of Internet addiction and other psychopathology. In terms of assessing potential comorbidities, the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV mental disorders[64] was used by five studies[32,50,93,106,164]. Psychopathological symptomatology was also assessed using the Symptom-Checklist, SCL-90-R[125,191] and the Chinese version of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview[115]. Personality disorders were identified by using the Dimensional Assessment of Personality Pathology-Short Form[58,59]. Other addiction-related assessments included alcohol and drug addiction measured with the DÉBA[76], the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test-Korean version[95], and the Severity of Alcohol Dependence Questionnaire[205], as well as shopping addiction, assessed via the Compulsive Buying Scale[54]. The presence of eating disorders was assessed using the Eating Disorder Inventory 2[52,53]. Mood disorders were assessed using the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression[39], Beck’s Depression Inventory[132], and the Mood Disorder Questionnaire[198]. Levels of anxiety were measured with the Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety[40], Beck’s Anxiety Inventory[74], and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7)[127]. Symptoms of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) were investigated by means of Conners’ Adult ADHD Rating Scales Self (CAARS:S)[42]. Finally, dissociation and depersonalisation were measured using the Dissociative Experiences Scale[34] and the Cambridge Depersonalization Scale[128].

The results of comorbidity and differential diagnosis analyses revealed the following. Of 50 adult outpatients self-referred for their Internet overuse, 14% presented with comorbid ADHD, 7% hypomania, 15% GAD, 15% social anxiety disorder, 7% dysthymia, 7% obsessive compulsive personality disorder, 14% borderline personality disorder, 7% avoidant personality disorder, and 2% binge eating disorder[32]. Higher frequencies of comorbid psychopathology were reported in a sample of 30 male patients with Internet gaming addiction[62], namely 40% antisocial personality traits, 56.7% affective disorders (30% major depression and 26.7% dysthymia), 26.7% other addictions (13.3% gambling, 10% alcohol, 10% marihuana, 6.7% nicotine and 3.3% cocaine addiction), and 16.7% antisocial disorders (13.3% ADHD, social phobia 10% and 3.3% dysmorphic corporal disorder). Generally smaller prevalence rates were reported in a sample of 57 Internet addiction treatment seekers in Canada[72]: 3.5% presented with comorbid depression and 7.5% with anxiety.

Half of a sample of 50 students with Internet addiction[79] presented with a comorbidity of another Axis I disorder (10% with major depression, 5% with dysthymia and psychotic disorders, respectively). This finding was corroborated by another study of 290 male treatment seekers, half of whom met criteria for another psychiatric disorder[124]. In addition to this, of the former sample, 38% presented with a concurrent Axis II personality disorder (22% with narcissistic, and 10% with borderline disorder, respectively)[79]. Significantly higher levels of depression and dissociation were furthermore found in a sample of 25 patients with Internet addiction as compared to a matched healthy control group[164]. Moreover, relative to a control group of male patients treated for alcohol addiction, 71 male patients with alcohol addiction and comorbid Internet addiction presented with higher levels of depression and obsessive-compulsive symptoms[188]. Furthermore, another study[197] including 368 Internet addiction treatment seekers showed that 30.9% met the diagnostic criteria for bipolar spectrum disorders, and this study also evidenced generally increased psychopathological symptomatology (including substance use disorders, affective and personality disorders). Finally, significant positive correlations were reported between compulsive buying and compulsive Internet use, as 11.7% of a sample of 60 female patients displaying patterns of compulsive buying also presented with addictive Internet use. This study reported no differences between individuals presenting with different types of eating disorders regarding compulsive Internet use[50].

Moreover, patients with Internet addiction and patients with pathological gambling received higher scores on depression, anxiety[26,27], and lower scores on global functioning relative to healthy controls, used impulsive coping strategies, and experienced more socio-emotional impairment. Additionally, patients with Internet addiction differed from patients with pathological gambling in that the former experienced higher mental and behavioural disengagement, which was found to be associated with interpersonal impairments[26].

Overall, the presence of comorbidities for Internet-use related addiction in the clinical context appears to be the norm rather than an exception. Individuals seeking treatment for their Internet overuse frequently present with mood and anxiety disorders, and other impulse-control and addictive disorders appear common. This indicates Internet addiction treatment may benefit from therapeutic approaches that combine evidence-based treatments for co-occurring disorders in order to increase treatment efficacy and acceptability for the patient.

In five studies, psychopharmacotherapy[20,22,24,28,46] for online addictions was used. Atmaca[28] reported the case of a 23-year-old male 4th year medical student who presented with the problems of problematic Internet use and anxiety. The patient was treated with a combination of selective serotonine reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) and antipsychotic medication. The antidepressant citalopram was administered at a dose of 20 mg/d and was increased to 40 mg/d within the period of a week, which was continued for six weeks. Subsequently, quetiapine (an atypical antipsychotic typically used for schizophrenia spectrum disorders) was added to the treatment, starting with a dose of 50 mg/d, which was increased to 200 mg/d within four days. The treatment resulted in decreased Internet addiction as measured with the Y-BOCS[30] modified for Internet use, decreased non-essential and essential Internet use, and improved control over Internet use. The improvements persisted until four-month follow up.

Bipeta et al[46] compared 34 control subjects with or without Internet addiction assessed via Young’s Diagnostic Questionnaire[48] with patients with pure OCD with or without Internet addiction (mean age = 27 years, SD = 6.5 years). OCD patients were treated with standard pharmacological treatment for OCD (treatment as usual) for one year, received the benzodiazepine clonazepam (often used in the treatment of anxiety disorders), which was tapered off in three weeks, an SSRI or the tricyclic antidepressant clomipramine for 12 mo. The individuals with Internet addiction in the OCD group received the following doses of medication: Five patients received 150-200 mg fluvoxamine/d, four received 150-200 mg sertraline/d, one received 60 mg fluoxetine/d, and the final one received 200 mg clomipramine/d. In the OCD group that included individuals who were not addicted to using the Internet, the following doses of medication were administered: Eight patients received 150-300 mg fluvoxamine/d, five received 100-200 mg sertraline/d, eleven received 40-80 mg fluoxetine/d, and three received 150-200 mg clomipramine/d. Overall, the OCD treatment improved scores for both OCD and Internet addiction, while only two of the eleven OCD patients still fulfilled Internet addiction criteria after twelve months of treatment[46].

Dell’Osso et al[20] assessed the safety and efficacy of the antidepressant SSRI escitalopram (typically used for mood disorders) in 19 adult patients (12 men, mean age = 38.5, SD = 12.0 years) who presented with the problem of impulsive-compulsive Internet usage disorder assessed via the YBOCS[30], modified for Internet use. The trial consisted of a total of 19 wk, composed of a ten week treatment phase in which escitalopram was administered starting with 10 mg/d, and increased and maintained at 20 mg/d for 10 wk, and subsequent nine weeks of a randomised double-blind placebo controlled trial with or without administration of escitalopram at previous dosages. The treatment phase resulted in a significant decrease in Internet use. However, there were no differences in treatment effect between the treatment and placebo group following the second stage of the study. The authors also note that the group treated with escitalopram experienced negative side effects, including fatigue and sexual side effects, whereas side effects did not occur in the placebo group[20].

Han et al[26] used a controlled trial to test the effects of the antidepressant bupropion sustained release treatment (with a dose of 150 mg/d for the first week and 300 mg/d for five subsequent weeks) on the brain activity of eleven Internet video game addicts (mean age = 21.5, SD = 5.6 years), assessed via Young’s Internet Addiction Scale[216]. The results indicated that the administered psychopharmacological treatment provided successful results for the video game addiction group, as it decreased craving, playing time, and cue-induced brain activity. These authors[22] also used the central nervous system stimulant concerta (methylphenidate commonly used for ADHD) in 62 video game playing children with ADHD (52 males, mean age = 9.3, SD = 2.2 years) who had not previously been given medication. Internet addiction was assessed using the Korean version of Young’s Internet Addiction Scale[87]. The initial concerta dosage was 18 mg/d, with the maintenance dosage being individually adjusted based on the respective children’s clinical symptoms and weight. Following treatment, Internet addiction and Internet use significantly decreased, as did ADHD symptoms and omission errors in a Visual Continuous Performance Test[22].

Taken together, the studies including psychopharmacological treatment for Internet addiction and/or gaming addiction showed positive effects in decreasing Internet addiction symptomatology and Internet/gaming use times. In the few studies conducted, antidepressant medication has been used most, suggesting mood disorders may be comorbid with Internet use addiction. The research also indicated that if other (primary or secondary) disorders are present (specifically, OCD and ADHD), medication typically used to treat these disorders is also effective in reducing Internet addiction-related problems.

Ten studies[23,65,86,119,136,149,174,201-203] described some form of psychological therapy for treating Internet addiction. The majority of psychological therapies used an individual approach, which was applied to outpatients, apart from three studies that used group therapy approaches[23,65,119,136,149].