Published online Jun 22, 2015. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v5.i2.228

Peer-review started: December 6, 2014

First decision: January 20, 2015

Revised: February 18, 2015

Accepted: March 16, 2015

Article in press: March 18, 2015

Published online: June 22, 2015

Processing time: 196 Days and 11.8 Hours

AIM: To describe a model outpatient competence restoration program (OCRP) and provide data on time to restoration of adjudicative competence.

METHODS: The authors tracked the process by which individuals are referred for outpatient competence restoration (OCR) by courts in the United States capital, describing the unique requirements of American law, and the avenues available for compelling adherence. Competence to stand trial is a critical gate-keeping function of the judicial and forensic communities and assures that defendants understand courtroom procedures. OCR is therefore an effort to assure fairness and protection of important legal rights. Multi-media efforts are described that educate patients and restore competence to stand trial. These include resources such as group training, use of licensed clinicians, visual aids, structured instruments, and cinema. Aggregate data from the OCRP’s previous 4 years of OCR efforts were reviewed for demographic characteristics, restoration rate, and time to restoration. Poisson regression modeling identified the differences in restoration between sequential 45-d periods after entrance into the program.

RESULTS: In the past 4 years, the DC OCRP has been successful in restoring 55 of 170 participants (32%), with an average referral rate of 35 persons per year. 76% are restored after the initial 45 d in the program. Demographics of the group indicate a predominance of African-American men with a mean age of 42. Thought disorders predominate and individuals in care face misdemeanor charges 78% of the time. Poisson regression modeling of the number attaining competence during four successive 45-d periods showed a substantial difference among the time periods for the rate of attaining competence (P = 0.0011). The three time periods after 45 d each showed a significant decrease in the restoration rate when compared to the initial 0 to 45 d period - their relative rates were only 22% to 33% as high as the rate for 0-45 d (all P-values, compared to the 0-45 d rate, were 0.013 or smaller). However, the three periods from day 45 to day 135 showed no difference among themselves (P = 0.87).

CONCLUSION: The majority of restored participants were restored after 45 d, suggesting a model that may identify an optimal length of time to restoration.

Core tip: Restoring a defendant’s competence to stand trial is a cardinal element of public sector forensic services in the United States. The Washington DC outpatient competence restoration program (OCRP) is one of a number of state programs that offers a model of education and support for incompetent defendants. Using a combination of specialized assessment, multi-modal education, support, and court leverage, the DC OCRP is the first to identify the length of time most useful for restoring its referral population. Implications of these findings can affect the court calendar, further research, and inter-agency collaboration.

- Citation: Johnson NR, Candilis PJ. Outpatient competence restoration: A model and outcomes. World J Psychiatr 2015; 5(2): 228-233

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v5/i2/228.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v5.i2.228

Outpatient competence restoration (OCR) is a function of United States law that provides outpatient competency education to non-dangerous defendants who are found incompetent to stand trial. Competency is defined by a 1960 United States Supreme Court case, Dusky v. United States, which affirmed a defendant’s right to a competency evaluation before proceeding to trial. In this landmark case, the court outlined the basic standards for determining competency, ruling that a defendant must have a “sufficient present ability to consult with his lawyer with a reasonable degree of rational understanding” and a “rational as well as factual understanding of the proceedings against him”[1]. The standard draws on fundamental principles of fairness to establish that it is both unlawful and unethical for defendants to proceed in a criminal matter without an understanding of the proceedings, its consequences, and the ability to assist their attorneys.

The OCR program (OCRP) in Washington DC is unique in that it serves international defendants who travel for the express purpose of communicating with the White House or United States Congress. Cultural nuances are therefore a critical component of local competency restoration. Individuals from Romania, for example, cannot bear witness if their trial is heard in Romania. In the United States, they must be taught that they can indeed be a witness in their own defense. South African citizens may not be familiar with a jury-based system. Because of racial prejudice and inequality the jury system was formally abolished there in 1969[2]. In the District of Columbia, South African defendants facing a felony charge must be informed of the possible benefits and safeguards of having a jury of peers deciding their case.

There are an estimated 25000 to 39000 competency evaluations conducted annually in the United States[3,4]. After defendants are deemed incompetent by a judge applying the Dusky standard, they may be committed to restoration in an inpatient or outpatient setting. Dangerousness determines the location, but is also governed by the resources of the state and the judgment of the fact-finder (i.e., the judge).

Thirty-five states have specific statutes that allow for OCR. However, only 16 states actually have a functioning OCRP. Some states, New York for example, only restore individuals who are charged with a felony, a serious charge generally carrying a sentence of over a year in prison. In the District of Columbia, a defendant can be ordered to participate in either inpatient restoration at Saint Elizabeths Hospital, the District’s publicly funded hospital, or to outpatient restoration at the OCRP in the DC Department of Behavioral Health. The outpatient option adheres to the statutory requirement of providing the least restrictive alternative for mental health orders.

Other states with OCRPs include Arizona, Georgia, Louisiana, Ohio, Texas, Virginia, West Virginia and Wisconsin. Wisconsin provides one-on-one competency education to defendants for one hour twice a week. Competency restoration specifically includes case management services which are provided once a week to each participant. This assures that participant schedules are coordinated, appointments made, and that contact with the program is maintained. In 2012-13, Wisconsin served 121 defendants, restoring them at a rate of 75% - among the highest rates in the nation[5].

Texas follows a group-structured competency restoration program with the option of one-on-one service[6]. Groups meet daily for 1-1.5 h. Between 2008 and 2013, the overall rate of restoration was 42%. The stark difference between this program and the DC OCRP is the availability of involuntary medication in the outpatient setting. DC does not have this option, leading to delays in treatment that affect time to restoration. Programs with legal leverage of this kind can greatly increase restoration rates by enforcing the intense exposure and structure needed to teach defendants the critical elements of the legal system. Moreover, patient adherence to medication regimens decreases the symptoms of mental illness that interfere with the ability to order and retain new material.

Judicial responses to persons not adhering to the initial court order include an order to return to OCRP, an order for inpatient competency restoration, dismissal of charges, the issuance of a bench warrant, or a finding of unlikely to be restored. Bench warrants for a return to court are generally issued to participants who do not comply with the initial court order and do not appear for OCR.

Compared to inpatient restoration, OCRP provides easily recognizable benefits to the defendant and the healthcare system. It is conducted in a less restrictive environment, provides less encroachment on personal liberty, is less disruptive of daily life, and offers cost savings to defendants and the public health system alike.

DC evaluators are board-certified forensic psychiatrists and forensically experienced psychologists who must have completed a forensic psychiatry fellowship or supervised experience with a trained clinician. This includes observing competency evaluations and then conducting at least five evaluations under direct supervision. Successful completion of this additional course of training provides acculturation to the program and its constituents, improved understanding of regulations, familiarity with local cultures and interpretations of law, and the proper thresholds for ascribing competence.

The DC OCRP meets at an outpatient clinic in the center of the District of Columbia. Participants are court-ordered to participate and screened for suitability by a psychologist who performs a full introductory evaluation of competence to stand trial. Individuals with violent charges or who cannot be adequately contained in the community are not recommended for the program. However, 71% of those who participate receive mental health services while enrolled in OCRP. Individuals who do not adhere to their appointment schedule or who are disruptive to the group process are identified and the court is alerted in writing. The court ultimately decides whether the defendant continues in OCRP or whether an alternative option like hospitalization is appropriate.

OCR takes place in a group setting. The group meets twice a week for 1.25 h at a time. The first visit essentially serves as an intake session where the group facilitator collects demographic information, obtains the defendant’s signature on a formal participation agreement, and reviews the purpose of the program along with the expectations of those attending. These are essential elements of an informed consent process that discloses information about the program, contributes to the assessment process, and encourages the participant’s engagement. If defendants are receiving community mental health services, they are asked to sign a release of information so that treatment needs and adherence can be confirmed.

Defendants are asked to read the program’s main teaching tool, a 42-question survey loosely based on the Florida State Hospital CompKit[7]. Used broadly to assess the factual prong of the Dusky standard (i.e., “a factual understanding of the proceedings against him”), the instrument ascertains the defendants’ ability to read and understand the curriculum’s competency information. This is an important adjunct to the initial competence evaluation.

The OCRP groups are facilitated by a licensed clinical mental health provider, currently a master’s level social worker, as well as a mental health provider who provides support to the facilitator. Various teaching tools are utilized, depending on the needs of the group. The 42-question survey is studied in each session so that part-by-part review can improve recall and understanding of the material. In addition, the facilitator uses visual aids, like pictures of a courtroom on a magnetic board, to reach participants whose preferred learning modality is visual or who may be cognitively impaired (These materials are not publicly available so that attorneys and defendants do not gain unfair advantage before the formal assessment and restoration efforts).

Case vignettes drawn from the media are selected for discussion. The connection to current events anchors the curriculum in real-life events, lending an urgency and specificity to the curriculum. Feedback from participants over the years indicates that this is a particularly effective manner to underscore the identity of courtroom participants and engage group members. Role play is a useful strategy in this context as well, as participants act out the roles of courtroom members.

Each quarter, the facilitator shows the movie “My Cousin Vinnie”, a Hollywood comedy recounting the adventures of an ersatz city lawyer trying to disentangle his cousin from a rural court. Participants consequently discuss the movie’s relevance to the real courtroom. Finally, the facilitator uses word association and acronyms to help participants retain the material. This approach underscores the visual and kinesthetic elements of the program and offers mnemonics that can easily be recalled.

Each defendant is consequently evaluated by a forensic psychiatrist after 45 d (the length of the initial court order), and each 30 d thereafter. Reports are written by the same examiner to support reliability, and describe whether or not the defendant is competent to stand trial along with recommendations for continued restoration if needed.

Statistical analysis was overseen and conducted by biomedical statistician Robert W Wesley, PhD.

The cost to run the DC OCRP is $2006/wk in 2014 US dollars, compared to the cost of inpatient restoration at $6307/wk. Although the majority of costs are for personnel, considerable savings accrue from using licensed, clinical mental health professionals rather than medical doctors or psychologists to facilitate the group sessions. Physicians and psychologists are reserved for the competency evaluations themselves. Moreover, basing the program on a group treatment model creates an economy of scale that allows staff access to more individuals at one time. The subsequent analysis has been exempted from review by the DC Department of Behavioral Health institutional review board.

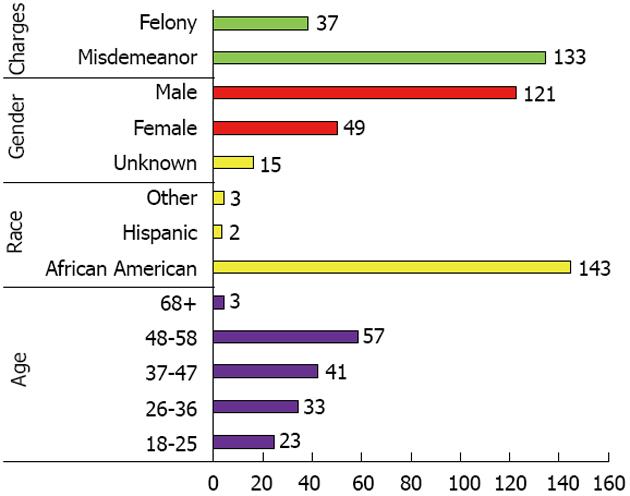

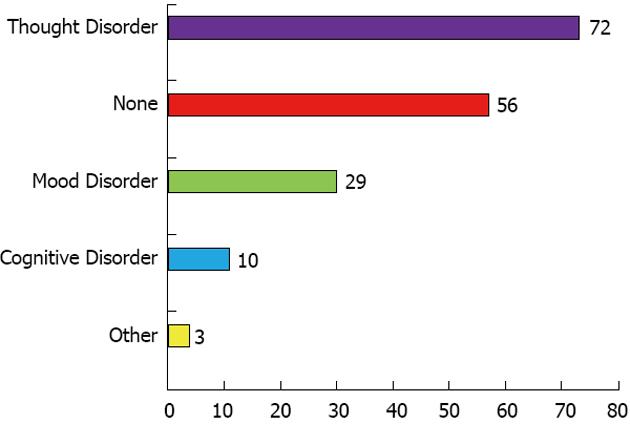

In the past four years, the DC OCRP has been successful in restoring 55 of 170 participants (32%), with an average referral rate of 35 persons per year[8]. Demographics of this group are presented in Figures 1 and 2, and indicate a predominance of African-American men.

With a mean age of 42, participants were largely in the 37-58 year age range, and faced misdemeanor charges 78% of the time.

Because they were frequently returned to the program by court order for continued competency restoration, the 170 participants generated 274 court orders. During 2009-2013, 70 of 170 total participants were ordered to return to OCRP after 45 d. This number dropped precipitously to 24 after 75 d in OCRP, and again thereafter as the rules of the program took hold. After 45 d of participating in bi-weekly OCRP, 28 participants were ordered to receive restoration and treatment on an inpatient basis (50 within 135 d). Three participants were ordered to inpatient restoration and treatment after being in OCRP for 135 d.

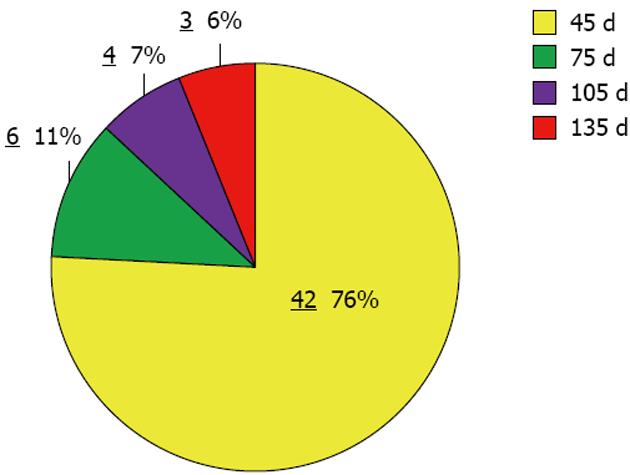

Forty-two of the 55 participants successfully restored were found competent after the first 45 d of participation. After 75 d of participating in OCRP, six more attained competence. After 105 d, four more were restored, and by 135 d all 55 participants were deemed competent to stand trial (Figure 3).

Poisson regression modeling of the number attaining competence during these four time periods, showed a substantial difference among the time periods for the rate of attaining competence (P = 0.0011). The three time periods after 45 d each showed a significant decrease in the restoration rate when compared to the initial 0 to 45 d period - their relative rates were only 22% to 33% as high as the rate for 0-45 d (all P-values, compared to the 0-45 d rate, were 0.013 or smaller). However, the three periods from day 45 to day 135 showed no difference among themselves (P = 0.87).

Eleven participants had their charges dismissed after being in the program for 45 d. This number dropped to ten participants after 75 d and four participants after 105 d of being ordered to the program. A total of 28 participants, 21 facing misdemeanors, had their charges dismissed by 135 d (only 9 more after 135 d).

Five bench warrants were issued after the first 45 d, with an additional two bench warrants issued after 75 d, and only one after 135 d in the program.

Five participants were determined to be unlikely to be restored in the foreseeable future and a Jackson finding was issued after 45 d. This order is based on the United States landmark case of Jackson v. Indiana which requires that confinement for OCR bear some relationship to the initial reason for incarceration[9]. Defendants cannot be held indefinitely. Seven participants were determined to be unlikely to be restored after 75 d, with one additional participant added after 135 d, and another after 165 d.

These data indicate that the first 45 d of participation in the DC OCRP are the most productive. To our knowledge this is the first report to identify an optimal length of time to restoration in the outpatient forensic setting. The substantial majority (76%) of participants found competent were restored after 45 d in the program. The type of leverage used by the courts (e.g., bench warrants, return orders) decreased significantly after 45 d and another significant participant group had their charges dismissed. The increase in Jackson findings (i.e., that participants are unrestorable) after 45 d indicates the power of the 45 d period to determine competence.

Twenty-eight defendants, mostly facing misdemeanor charges, had their charges dismissed by 135 d after their initial order into competency restoration. We hypothesize that judges recognize that defendants may spend more time attempting to become competent than serving the short sentence they are likely to face after a misdemeanor. It is not surprising, therefore, that this group faced dismissal despite not attaining competence.

The importance of adequate time for group education and multi-media efforts to take hold is an important predicate of outpatient restoration and matches findings in the psychiatric literature supporting multi-modal efforts for patient education[10,11]. The group process is critical here, as in other modalities for improving patient care, from cognitive-behavioral therapy to addictions[12,13].

Use of forensically trained evaluators who have undergone local supervision underscores familiarity with local statutes, cultures, and legal interpretations. The broad range of ethnicities and nationalities in Washington DC requires regular updating on cultural norms and legal experiences outside the United States. This is achieved by peer support and supervision among evaluators and educators.

There continue to be barriers for OCRP programs in general and DC in particular. The need for programming for those with cognitive limitations could be especially useful in a population that often suffers educational or developmental delays[14,15]. Growth of programs useful in other settings could be essential to restoring the participants who do not attain competence after initial attempts[16]. The local Department of Disability Services may be an especially effective partner, since it has already developed programs to support and educate their clients with developmental disabilities.

As effective as groups are in allowing education for a large number of participants, even group size can interfere with productivity. The size for schizophrenia therapy groups has often been reported at fewer than ten patients, with larger groups potentially interfering with group education and process[17,18]. Identifying the size at which restoration groups attain optimum performance may be an important outgrowth of research in this area.

As some states have recognized, case management services are critical for addressing restorability as well as assessing the use of clinical and forensic services. The factors known to affect one’s ability to become competent include employment, treatment adherence, and abstinence from substance use[19,20]. Support in these areas can be health-affirming as well as cost-effective. Transportation assistance can be particularly useful in improving access to forensic and community services that assure the fairness of the judicial process.

As practiced in the District of Columbia, therefore, OCR is an effective intervention for assuring the fair use of the courts. Governed by landmark court cases and local law, the OCRPs in general offer a range of educational resources and support for those who cannot successfully navigate the judicial system. Frequently achievable within 45 d in DC, OCR relies on expert assessment, group process, multi-media interventions, and leverage from the courts. Future challenges arise from the presence of participants with cognitive difficulties and the need for more research on optimal group size, transportation needs, and inter-agency collaboration.

We are grateful to biostatistician Robert Wesley, PhD, for his assistance with the statistical analysis, and to Doshia Kelly, BS, and Frances Alves, MSW for their efforts in data collection.

This study examines an outpatient competence restoration program (OCRP) and its effectiveness in restoring adjudicative competence in the least restrictive environment. In a period when budgetary constraints influence clinical services, outpatient competence restoration (OCR) is an effective and cost-saving tool for providing a necessary service required by United States law. Providing multi-media group education in an outpatient setting alongside competency evaluation conducted by forensic clinicians is a cardinal feature of the OCRP in Washington DC. This study provides a look into a model OCRP and its data in hopes that jurisdictions not yet utilizing this service will develop programs that simultaneously meet the needs of the criminal justice system while protecting the civil liberties of the mentally ill.

There is little information in the literature on the specifics of OCRPs. This is the first time, to our knowledge, that the specific methods of an OCRP are described and its aggregate data examined. This project may consequently allow other jurisdictions to compare their methods and data as they develop or modify new programs.

The multi-media approach to education of persons diagnosed with mental illness finds a new application in the outpatient forensic setting. This combination of educational efforts and forensic resources represents a unique effort to protect the rights of vulnerable individuals interacting with the judicial system. The combination of specific educational methods and aggregate data offers a unique look at the inner workings of a potentially model program.

The specific educational and resource information offered here, as well as its effect on OCR, can provide the framework for jurisdictions seeking to develop evidence-based programs that protect the civil liberties of persons diagnosed with mental illness.

Competency restoration: The educational process followed by defendants found incompetent to stand trial; Adjudicative competence or competence to stand trial: The critical elements of courtroom procedures, participants, and reasoning that allow defendants to collaborate meaningfully in the judicial process.

A well conducted study and the results are concise with a good discussion and literature survey.

| 1. | Dusky v United States. 362 U.S. 402. 1960. Available from: https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/362/402/case.html. |

| 2. | South Africa Abolition of Juries Act 34, 1969. Available from: https://www.nelsonmandela.org/omalley/index.php/site/q/03lv01538/04lv01828/05lv01829/06lv01939.htm. |

| 3. | Hoge SK, Bonnie RJ, Poythress N, Monahan J, Eisenberg M, Feucht-Haviar T. The MacArthur adjudicative competence study: development and validation of a research instrument. Law Hum Behav. 1997;21:141-179. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Steadman HJ, Hartstone E. Defendants incompetent to stand trial. In Monahan J and Steadman HJ (Eds.). Mentally disordered offenders: Perspectives from law and social science. New York: Plenum 1983; 39-62. |

| 5. | Outpatient Competence Restoration Program of Behavioral Consultants, Inc. [accessed 2014 November 25]. Available from: www.bciwi.com. |

| 6. | Texas Department of State Health Services. [accessed 2014 November 25]. Available from: www.dshs.state.tx.us. |

| 7. | Florida State Hospital CompKit, Competence to Stand Trial Resources. [accessed 2014 November 25]. Available from: www.mentalcompetency.org/resources/restoration/files/FLStCompKit.pdf. |

| 8. | 2014 Quarterly Report to the Pre-Trial Mental Examination Committee. Washington DC: Superior Court 2014; . |

| 9. | Jackson v Indiana, 406 U.S. 715, 1972. Available from: https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/406/715/. |

| 10. | Eack SM, Hogarty GE, Cho RY, Prasad KM, Greenwald DP, Hogarty SS, Keshavan MS. Neuroprotective effects of cognitive enhancement therapy against gray matter loss in early schizophrenia: results from a 2-year randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:674-682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 251] [Cited by in RCA: 241] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Jeste DV, Palmer BW, Golshan S, Eyler LT, Dunn LB, Meeks T, Glorioso D, Fellows I, Kraemer H, Appelbaum PS. Multimedia consent for research in people with schizophrenia and normal subjects: a randomized controlled trial. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:719-729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Feng CY, Chu H, Chen CH, Chang YS, Chen TH, Chou YH, Chang YC, Chou KR. The effect of cognitive behavioral group therapy for depression: a meta-analysis 2000-2010. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2012;9:2-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | McCrady BS, Owens MD, Borders AZ, Brovko JM. Psychosocial approaches to alcohol use disorders since 1940: a review. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2014;75 Suppl 17:68-78. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Maurel M, Belzeaux R, Adida M, Fakra E, Cermolacce M, Da Fonseca D, Azorin JM. [Schizophrenia, cognition and psychoeducation]. Encephale. 2011;37 Suppl 2:S151-S154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Pekkala E, Merinder L. Psychoeducation for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;CD002831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Therapeutic Learning Center (TLC)-Competency Restoration Program. Washington DC: Saint Elizabeths Hospital; . |

| 17. | Moritz S, Kerstan A, Veckenstedt R, Randjbar S, Vitzthum F, Schmidt C, Heise M, Woodward TS. Further evidence for the efficacy of a metacognitive group training in schizophrenia. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49:151-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Farreny A, Aguado J, Ochoa S, Huerta-Ramos E, Marsà F, López-Carrilero R, Carral V, Haro JM, Usall J. REPYFLEC cognitive remediation group training in schizophrenia: Looking for an integrative approach. Schizophr Res. 2012;142:137-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hubbard KL, Zapf PA, Ronan KA. Competency restoration: an examination of the differences between defendants predicted restorable and not restorable to competency. Law Hum Behav. 2003;27:127-139. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Mossman D. Predicting restorability of incompetent criminal defendants. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2007;35:34-43. [PubMed] |

P- Reviewer: Allen M, Gürel P, Krishnan T S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Yan JL

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/