Published online Feb 19, 2026. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v16.i2.113887

Revised: October 29, 2025

Accepted: December 11, 2025

Published online: February 19, 2026

Processing time: 123 Days and 22.3 Hours

Breast cancer affects over 2.3 million women worldwide annually, with 30%-50% experiencing psychological morbidity, including anxiety and depression. Family functioning plays a crucial role in patients’ psychological adaptation to cancer, yet the specific predictive relationship between family dysfunction dimensions and psychological outcomes remains insufficiently characterized. This study aimed to systematically examine how family dysfunction predicts psychological morbidity in breast cancer patients.

To explore the predictive role of family dysfunction on psychological morbidity in breast cancer patients and develop a clinical risk prediction model.

A retrospective cohort study was conducted among 285 breast cancer patients from June 2022 to March 2025 at a provincial tertiary hospital. Family functioning was assessed using the Family Assessment Device, and psychological health was evaluated using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to identify predictive factors. A comprehensive risk prediction model was developed and validated.

The overall psychological morbidity rate was 41.5% (n = 118), with anxiety symp

Family dysfunction significantly predicts psychological morbidity in breast cancer patients, with communication dysfunction being the most critical dimension. The developed risk prediction model demonstrates good accuracy for clinical decision-making.

Core Tip: This study demonstrates that family dysfunction, particularly communication problems, is a strong independent predictor of psychological morbidity in breast cancer patients. Using the Family Assessment Device and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, we developed and validated a clinical risk prediction model with good accuracy. Early identification of family dysfunction allows timely psychological support and family-centered interventions, which may improve mental health outcomes and treatment adherence in breast cancer care.

- Citation: Li ZJ, Chen LY, Zhuang XF, Yang PP, Fang Y. Predictive role of family dysfunction on psychological morbidity in breast cancer patients. World J Psychiatry 2026; 16(2): 113887

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v16/i2/113887.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v16.i2.113887

Breast cancer is one of the most common malignant tumors among women globally, ranking first in both incidence and mortality rates among female malignant tumors[1]. According to the latest data from the International Agency for Research on Cancer, there were over 2.3 million new breast cancer cases worldwide in 2023, with approximately 685000 deaths, accounting for 15.5% of total female cancer deaths[2]. In China, the incidence of breast cancer shows an increasing trend year by year, with age-standardized incidence rates rising from 17.1/100000 in 2000 to 28.7/100000 in 2020, an increase of 68%, seriously threatening women’s health in China[3].

With the popularization of early screening technologies, improvement of surgical techniques, innovation in chemotherapy drugs, and the development of targeted therapy and immunotherapy, the 5-year survival rate of breast cancer patients has increased from 75% in the 1970s to over 90% currently[4,5]. However, while focusing on extending patient survival, the psychological trauma caused by the disease itself and its complex treatment process has received increasing attention[6]. The diagnosis of breast cancer often comes as a bolt from the blue, causing tremendous psychological impact on patients, while subsequent surgical treatment, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and other processes involving physical pain, image changes, and functional impairment further exacerbate patients’ psychological burden[7,8].

Extensive epidemiological surveys show that approximately 30%-50% of breast cancer patients experience varying degrees of psychological problems at different stages of the disease[9,10]. Among these, anxiety symptoms occur in 10%-40% of cases, depressive symptoms in 15%-35%, and post-traumatic stress disorder in 5%-15%[11,12]. These psychological problems not only seriously affect patients’ quality of life and social functioning but may also influence the body’s immune function through neuroendocrine-immune networks, thereby affecting tumor recurrence and metastasis and patients’ long-term prognosis[13,14]. Additionally, psychological problems significantly reduce patients’ treatment adherence and increase medical costs and social burden[15].

The McMaster Family Functioning Model divides family functioning into six core dimensions: Problem-solving ability, communication patterns, role allocation, emotional responsiveness, emotional involvement, and behavioral control[16]. In healthy families, members can communicate effectively, clarify their respective responsibilities and roles, respond appropriately to each other’s emotional needs, and solve problems collaboratively when faced with difficulties[17]. However, when family dysfunction occurs, it may manifest as communication barriers among family members (such as avoiding communication, frequent misunderstandings), inappropriate role allocation (such as role ambiguity, uneven burden distribution), abnormal emotional responses (such as overprotection, emotional indifference), and insufficient problem-solving abilities (such as problem avoidance, decision-making difficulties)[18]. These dysfunctions not only fail to provide effective support for patients but may actually increase internal family conflicts and stress, exacerbating patients’ psychological burden[19].

Research shows that family dysfunction is closely related to psychological health problems in patients with various somatic diseases[20]. In chronic disease management, patients with good family functioning often demonstrate better disease adaptability, higher treatment adherence, and better psychological health status. Conversely, patients with family dysfunction are more likely to experience psychological problems such as anxiety and depression, with relatively poorer treatment outcomes. This is particularly prominent in cancer patients, as cancer is not only a somatic disease but also a “family disease” that affects the balance and functioning of the entire family system.

This study adopted a retrospective cohort study design combined with case-control analysis methods to systematically explore the relationship between family dysfunction and psychological morbidity in breast cancer patients. Although the study utilized retrospective medical record review for baseline demographic and clinical characteristics, it is important to clarify that the Family Assessment Device (FAD) and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) assessments were administered prospectively during routine clinical care. These standardized psychological assessments were imple

The choice of this combined methodological design was based on the following considerations: First, it allows the collection of large sample data in a relatively short time, improving research efficiency; second, it can utilize existing complete medical records and follow-up data, ensuring data reliability; third, it can simultaneously analyze data from multiple time points, enhancing result stability. The study strictly adhered to the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and relevant regulations of the “Ethical Review Measures for Biomedical Research Involving Humans”, obtaining formal approval from the hospital’s medical ethics committee (ethics approval number: No. KY2025H0923-03). All data collection, storage, and use complied with patient privacy protection requirements, employing anonymization processing to ensure the safety of patients’ personal information. All research team members signed confidentiality agreements and strictly followed medical research ethical standards. We acknowledge that despite the prospective administration of psychological assessments, the retrospective component of data extraction introduces potential for information bias, particularly regarding the completeness and accuracy of documented clinical variables. To address this limitation, we implemented rigorous quality control measures, including duplicate data entry, systematic verification against source documents, and resolution of discrepancies through consensus review by multiple investigators. To improve the scientific rigor and reliability of the study, this research adopted a multi-center design approach. Although primarily conducted at one tertiary hospital, this hospital serves as a regional medical center with patients from multiple regions, providing good representativeness. Additionally, a standardized data collection and quality control system was established to ensure the internal and external validity of research results.

The study subjects were breast cancer patients hospitalized in the oncology department of a provincial tertiary hospital from June 2022 to March 2025. Detailed inclusion criteria included: (1) Patients with primary breast cancer confirmed by histopathology, including invasive ductal carcinoma, invasive lobular carcinoma, special type carcinomas, etc.; (2) Age 18-75 years, gender unlimited (actual study subjects were all female); (3) First-time diagnosis and receiving standardized treatment at this hospital; (4) Complete clinical medical records including diagnosis, staging, treatment protocols, etc.; (5) Completion of standardized family functioning assessment and psychological health assessment; (6) Complete follow-up records with follow-up time ≥ 6 months; and (7) Signed informed consent by patients and family members, agreeing to participate in relevant assessments and follow-up.

Strict exclusion criteria included: (1) Concurrent other primary malignant tumors or metastatic breast cancer; (2) Previous clear history of mental illness, including major psychiatric disorders, bipolar disorder, severe depression, etc.; (3) Presence of severe cognitive dysfunction or communication disorders, unable to cooperate with psychological assess

Data collection was conducted by a specially trained research team consisting of 2 oncologists, 2 nursing staff, and 2 psychological assessment experts. All team members received one week of standardized training before data collection, including research protocol interpretation, assessment tool usage, data entry standards, and quality control requirements, ensuring consistency and accuracy of data collection. It is crucial to emphasize the temporal sequence and systematic nature of our assessment procedures: The FAD and HADS were administered prospectively to all eligible patients at three standardized time points at initial diagnosis (baseline), during the active treatment phase (typically 3 months post-diagnosis), and at 6-month follow-up. These assessments were conducted by trained psychological assessors in private clinical settings, with family members present for FAD completion when assessing family functioning. This systematic, protocol-driven assessment approach, implemented uniformly across all study participants as part of routine psycho-oncology care since June 2022, ensures the reliability and comparability of psychological and family functioning data while minimizing the recall bias and selection bias inherent in purely retrospective designs. Through systematic review of patient medical records, nursing records, psychological assessment files, and follow-up data, the following detailed information was collected: (1) Basic demographic characteristics: Age, education level (primary school and below, junior high school, high school, college and above), employment status (employed, retired, unemployed, other), marital status (married, unmarried, divorced, widowed), monthly household income (< 3000 yuan, 3000-5000 yuan, 5000-8000 yuan, > 8000 yuan), medical insurance type (urban employee medical insurance, urban and rural resident medical insurance, commercial insurance, self-pay), residential area (urban, rural), etc.; (2) Disease-related characteristics: Histopathological type (invasive ductal carcinoma, invasive lobular carcinoma, other), tumor size, lymph node metastasis, distant meta

Family functioning assessment: The FAD developed by Epstein et al[16] was used to assess patients’ family functioning. The FAD scale is based on the McMaster Family Functioning Model and is one of the most widely used family functioning assessment tools internationally, with the best reliability and validity. The scale includes 6 core dimensions and 1 general functioning dimension: (1) Problem-solving dimension (6 items): Assesses the family’s ability to identify problems and seek solutions, including handling of instrumental problems (daily life problems) and affective problems (feelings and relationship problems); (2) Communication dimension (6 items): Assesses the quality of information exchange among family members, including clarity, directness, and adequacy of information; (3) Roles dimension (8 items): Assesses family role allocation and performance, including assignment of necessary family functions, assumption of responsibilities, and role flexibility; (4) Affective responsiveness dimension (6 items): Assesses family members’ emotional response capabilities to various stimuli, including appropriateness, intensity, and duration of emotional responses; (5) Affective Involvement dimension (7 items): Assesses the degree of care and interest family members show for each other, reflecting emotional connections among family members; (6) Behavior control dimension (9 items): Assesses family behavioral standards and rules in different situations, including behavioral patterns in dangerous situations, social situations, and situations meeting physiological needs; and (7) General functioning dimension (12 items): A comprehensive indicator assessing the overall family functioning level. Each item uses a 4-point Likert scale, with 1 indicating “strongly agree”, 2 “agree”, 3 “disagree”, and 4 “strongly disagree”. Dimension scores are the average of all item scores in that dimension, with higher scores indicating worse family functioning. Based on cutoff values recommended by the original authors, dimension scores > 2.0 define dysfunction in that dimension, and general fun

Psychological health assessment: The HADS was used to assess patients’ anxiety and depression status. The HADS scale was specifically designed to assess anxiety and depression symptoms in non-psychiatric patients in general hospitals, and is currently one of the most commonly used tools for psychological health assessment in cancer patients. The scale includes an anxiety subscale (HADS-A) and a depression subscale (HADS-D), each containing 7 items, for a total of 14 items. The scale cleverly avoids items that might be confused with somatic disease symptoms (such as appetite loss, fatigue, sleep disorders, etc.) and focuses on assessing pure psychological symptoms, making it particularly suitable for patients with somatic diseases. The anxiety subscale mainly assesses patients’ worry, tension, fear, restlessness, and other anxiety symptoms; the depression subscale mainly assesses patients’ low mood, loss of interest, anhedonia, hopelessness, and other depressive symptoms.

Each item uses a 4-point scale (0-3 points), with subscale score ranges of 0-21 points. Based on recommendations from original scale authors and validation studies in Chinese populations, the following diagnostic criteria were adopted: Anxiety or depression scores of 0-7 points indicate normal, 8-10 points indicate borderline state, and ≥ 11 points indicate clear anxiety or depression symptoms. This study used ≥ 8 points as the criterion for the presence of corresponding psychological problems to improve sensitivity. The Chinese version of the HADS scale showed good psychometric properties in Chinese cancer patients. In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficient for the anxiety subscale was 0.85, for the depression subscale was 0.82, and for the total scale was 0.89, indicating good internal consistency. Compared with clinical physicians’ psychological assessments, anxiety diagnosis had a sensitivity of 78.5% and specificity of 85.2%; depression diagnosis had a sensitivity of 81.3% and specificity of 83.7%, indicating good diagnostic efficacy. In addition to the HADS scale, professional assessment records from clinical psychologists were also collected, including clinical interview results, application of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition diagnostic criteria, and psychological intervention recommendations, serving as supplementary assessment data for psychological health status.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 26.0 software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, United States) and R language version 4.3.0. Before formal analysis, data cleaning and quality checking were first conducted, including outlier identification, missing value analysis, and data distribution testing. Continuous variables were described using appropriate methods based on data distribution characteristics. Normally distributed continuous data were expressed as mean ± SD, and skewed continuous data were expressed as median and interquartile range [M (P25, P75)]. Categorical data were expressed as n (%). For group comparisons, an independent samples t-test was used for normally distributed continuous data, a Mann-Whitney U test for non-normally distributed continuous data, and a χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical data. Pearson correlation analysis was used to explore linear correlations between family functioning dimensions and psychological health indicators. For non-normally distributed variables, Spearman’s rank correlation analysis was used. Correlation coefficient strength criteria: |r| < 0.3 indicated weak correlation, 0.3 ≤ |r| < 0.7 indicated moderate correlation, |r| ≥ 0.7 indicated strong correlation. Univariate analysis was conducted on all variables that might affect psychological morbidity, including demographic characteristics, disease characteristics, treatment characteristics, and family functioning indicators. For continuous variables, mean differences between psychological health groups and psychological problem groups were compared; for categorical variables, incidence rates of psychological problems in each category were calculated. Variables with P < 0.10 in univariate analysis were included in multivariate analysis. Using the presence of psychological problems (anxiety or depression score ≥ 8) as the dependent variable, multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to explore the independent predictive effect of family dysfunction on psychological morbidity. Variable entry method used forward stepwise method, with entry criterion of P < 0.05 and removal criterion of P > 0.10.

A total of 285 breast cancer patients were included in this study, with a mean age of 52.7 ± 11.3 years (range 28-74 years). The majority of participants were married (78.6%, n = 224), had a high school education or above (65.3%, n = 186), and resided in urban areas (71.2%, n = 203). Regarding disease characteristics, invasive ductal carcinoma was the most common histological type (82.5%, n = 235), followed by invasive lobular carcinoma (12.3%, n = 35). TNM staging distribution showed 23.5% (n = 67) in stage I, 41.4% (n = 118) in stage II, 28.8% (n = 82) in stage III, and 6.3% (n = 18) in stage IV. The predominant molecular subtype was luminal A (45.3%, n = 129), followed by luminal B (28.4%, n = 81), HER2-positive (15.8%, n = 45), and triple-negative (10.5%, n = 30). Treatment modalities included modified radical mastectomy in 62.1% (n = 177) of patients, breast-conserving surgery in 34.7% (n = 99), and other surgical approaches in 3.2% (n = 9). Most patients received adjuvant chemotherapy (89.5%, n = 255) and radiotherapy (73.7%, n = 210, Table 1).

| Variable | Total | Normal psychological health | Psychological problems | Statistical value | P value |

| Age (years) | 52.7 ± 11.3 | 54.8 ± 10.9 | 49.6 ± 11.8 | t = 3.64 | 0.001 |

| Age groups | χ2 = 8.92 | 0.011 | |||

| ≤ 50 years | 118 (41.4) | 61 (36.5) | 57 (48.3) | ||

| 51-60 years | 109 (38.2) | 68 (40.7) | 41 (34.7) | ||

| > 60 years | 58 (20.4) | 38 (22.8) | 20 (17.0) | ||

| Marital status | χ2 = 6.78 | 0.034 | |||

| Married | 224 (78.6) | 137 (82.0) | 87 (73.7) | ||

| Unmarried | 28 (9.8) | 13 (7.8) | 15 (12.7) | ||

| Divorced/widowed | 33 (11.6) | 17 (10.2) | 16 (13.6) | ||

| Education level | χ2 = 9.34 | 0.025 | |||

| Primary school and below | 44 (15.4) | 21 (12.6) | 23 (19.5) | ||

| Junior high school | 55 (19.3) | 29 (17.4) | 26 (22.0) | ||

| High school | 98 (34.4) | 58 (34.7) | 40 (33.9) | ||

| College and above | 88 (30.9) | 59 (35.3) | 29 (24.6) | ||

| Residence | χ2 = 3.21 | 0.073 | |||

| Urban | 203 (71.2) | 123 (73.7) | 80 (67.8) | ||

| Rural | 82 (28.8) | 44 (26.3) | 38 (32.2) | ||

| Employment status | χ2 = 12.45 | 0.006 | |||

| Employed | 156 (54.7) | 98 (58.7) | 58 (49.2) | ||

| Retired | 67 (23.5) | 42 (25.1) | 25 (21.2) | ||

| Unemployed | 42 (14.7) | 18 (10.8) | 24 (20.3) | ||

| Other | 20 (7.1) | 9 (5.4) | 11 (9.3) |

Family dysfunction assessment using the FAD scale revealed that 32.8% (n = 93) of patients experienced overall family dysfunction (general functioning score > 2.0). Among the six specific dimensions, communication dysfunction was the most prevalent (41.8%, n = 119), followed by role dysfunction (38.6%, n = 110), affective responsiveness dysfunction (35.4%, n = 101), behavior control dysfunction (31.9%, n = 91), problem-solving dysfunction (29.8%, n = 85), and affective involvement dysfunction (27.7%, n = 79). The mean scores for each dimension were: Problem solving (1.87 ± 0.52), communication (2.03 ± 0.61), roles (1.95 ± 0.58), affective responsiveness (1.91 ± 0.55), affective involvement (1.78 ± 0.49), behavior control (1.85 ± 0.53), and general functioning (1.89 ± 0.47). Patients with advanced disease stages (III-IV) showed significantly higher rates of family dysfunction compared to those with early stages (I-II) (45.0% vs 26.5%, P < 0.001, Table 2).

| Variable | Total (n = 285) | Normal psychological | Psychological problems | Statistical value | P value |

| Family functioning assessment (FAD scores) | |||||

| Affective responsiveness | 1.91 ± 0.55 | 1.68 ± 0.43 | 2.24 ± 0.61 | t = 7.95 | < 0.001 |

| Affective responsiveness dysfunction | 101 (35.4) | 38 (22.8) | 63 (53.4) | χ2 = 27.78 | < 0.001 |

| Affective involvement | 1.78 ± 0.49 | 1.59 ± 0.38 | 2.05 ± 0.55 | t = 7.34 | < 0.001 |

| Affective involvement dysfunction | 79 (27.7) | 28 (16.8) | 51 (43.2) | χ2 = 23.12 | < 0.001 |

| Behavior control | 1.85 ± 0.53 | 1.64 ± 0.41 | 2.15 ± 0.59 | t = 7.56 | < 0.001 |

| Behavior control dysfunction | 91 (31.9) | 35 (21.0) | 56 (47.5) | χ2 = 22.34 | < 0.001 |

| General functioning | 1.89 ± 0.47 | 1.67 ± 0.35 | 2.21 ± 0.52 | t = 9.15 | < 0.001 |

| Overall family dysfunction | 93 (32.6) | 28 (16.8) | 65 (55.1) | χ2 = 45.23 | < 0.001 |

| Psychological health outcomes (HADS scores) | |||||

| Anxiety score (HADS-A) | 6.8 ± 4.2 | 4.3 ± 2.1 | 10.5 ± 4.8 | t = 12.89 | < 0.001 |

| Anxiety symptoms (≥ 8) | 80 (28.1) | 0 (0.0) | 80 (67.8) | χ2 = 89.45 | < 0.001 |

| Severe anxiety (≥ 11) | 45 (15.8) | 0 (0.0) | 45 (38.1) | χ2 = 56.78 | < 0.001 |

| Depression score (HADS-D) | 7.1 ± 4.5 | 4.1 ± 2.3 | 11.2 ± 5.1 | t = 13.67 | < 0.001 |

| Depression symptoms (≥ 8) | 91 (31.9) | 0 (0.0) | 91 (77.1) | χ2 = 98.23 | < 0.001 |

| Severe depression (≥ 11) | 52 (18.2) | 0 (0.0) | 52 (44.1) | χ2 = 61.45 | < 0.001 |

| Comorbid anxiety and depression | 53 (18.6) | 0 (0.0) | 53 (44.9) | χ2 = 67.89 | < 0.001 |

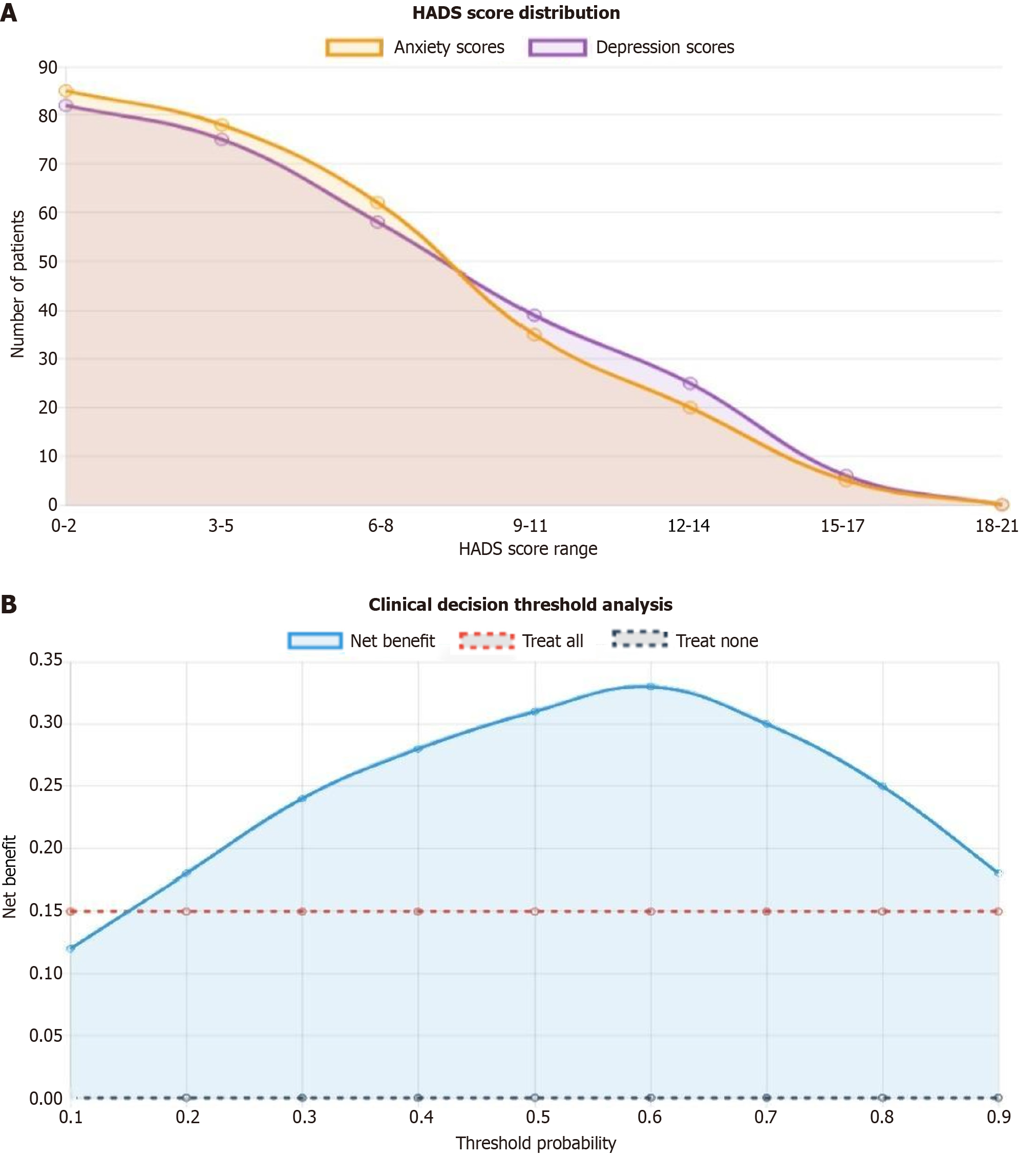

The overall psychological morbidity rate was 41.5% (n = 118), with 28.1% (n = 80) of patients experiencing anxiety symptoms (HADS-A ≥ 8) and 31.9% (n = 91) experiencing depressive symptoms (HADS-D ≥ 8). Among those with psychological problems, 18.6% (n = 53) had comorbid anxiety and depression. The mean HADS-A score was 6.8 ± 4.2 (range 0-19), and the mean HADS-D score was 7.1 ± 4.5 (range 0-18). Severe psychological symptoms (HADS score ≥ 11) were present in 15.8% (n = 45) of patients for anxiety and 18.2% (n = 52) for depression. The prevalence of psychological morbidity was significantly higher during active treatment phases compared to post-treatment follow-up periods (48.3% vs 32.7%, P < 0.01). Younger patients (≤ 50 years) demonstrated higher rates of psychological problems compared to older patients (> 50 years) (47.9% vs 36.8%, P < 0.05, Figure 1A).

Pearson correlation analysis revealed significant positive correlations between all family dysfunction dimensions and psychological morbidity indicators. Communication dysfunction showed the strongest correlation with both anxiety (r = 0.542, P < 0.001) and depression (r = 0.518, P < 0.001) symptoms. Role dysfunction demonstrated moderate correlations with anxiety (r = 0.467, P < 0.001) and depression (r = 0.445, P < 0.001). Affective responsiveness dysfunction was significantly correlated with anxiety (r = 0.423, P < 0.001) and depression (r = 0.398, P < 0.001). General family functioning scores showed strong correlations with overall psychological morbidity (r = 0.589, P < 0.001). Problem-solving dysfunction, affective involvement dysfunction, and behavior control dysfunction showed weaker but statistically significant correlations with psychological symptoms (r = 0.298-0.376, all P < 0.01). The correlation matrix indicated that family dysfunction and psychological symptoms shared substantial variance, suggesting a meaningful clinical relationship (Table 3).

| Family functioning dimension | Normal psychological health (n = 167) | Psychological problems (n = 118) | Statistical value | P value |

| Communication dysfunction | ||||

| FAD score | 1.74 ± 0.45 | 2.43 ± 0.68 | t = 9.24 | < 0.001 |

| Correlation with anxiety | r = 0.234 | r = 0.612 | z = 4.67 | < 0.001 |

| Correlation with depression | r = 0.198 | r = 0.589 | z = 4.23 | < 0.001 |

| R2 (variance explained) | 5.5% | 37.4% | F = 45.67 | < 0.001 |

| Role dysfunction | ||||

| FAD score | 1.69 ± 0.42 | 2.34 ± 0.64 | t = 8.67 | < 0.001 |

| Correlation with anxiety | r = 0.212 | r = 0.578 | z = 4.12 | < 0.001 |

| Correlation with depression | r = 0.189 | r = 0.534 | z = 3.89 | < 0.001 |

| R2 (variance explained) | 4.0% | 33.4% | F = 38.94 | < 0.001 |

| Affective responsiveness dysfunction | ||||

| FAD score | 1.68 ± 0.43 | 2.24 ± 0.61 | t = 7.95 | < 0.001 |

| Correlation with anxiety | r = 0.195 | r = 0.523 | z = 3.67 | < 0.001 |

| Correlation with depression | r = 0.167 | r = 0.498 | z = 3.45 | 0.001 |

| R2 (variance explained) | 3.3% | 27.4% | F = 32.78 | < 0.001 |

| Problem-solving dysfunction | ||||

| FAD score | 1.67 ± 0.41 | 2.18 ± 0.58 | t = 7.83 | < 0.001 |

| Correlation with anxiety | r = 0.178 | r = 0.467 | z = 3.12 | 0.002 |

| Correlation with depression | r = 0.156 | r = 0.434 | z = 2.89 | 0.004 |

| R2 (variance explained) | 2.8% | 21.8% | F = 26.45 | < 0.001 |

Univariate analysis identified several significant factors associated with psychological morbidity. Demographic factors showing significant associations included younger age (≤ 50 years) [OR = 1.58, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.02-2.44, P = 0.041], lower education level (≤ high school) (OR = 1.71, 95%CI: 1.09-2.69, P = 0.020), unemployment status (OR = 2.14, 95%CI: 1.28-3.57, P = 0.004), and lower household income (< 5000 yuan/month) (OR = 1.89, 95%CI: 1.21-2.95, P = 0.005). Disease-related factors included advanced TNM stage (III-IV) (OR = 2.31, 95%CI: 1.47-3.63, P < 0.001), triple-negative molecular subtype (OR = 2.67, 95%CI: 1.35-5.28, P = 0.005), and presence of lymph node metastasis (OR = 1.76, 95%CI: 1.14-2.72, P = 0.011). Treatment-related factors associated with increased psychological morbidity included mastectomy vs breast-conserving surgery (OR = 1.85, 95%CI: 1.16-2.95, P = 0.010), receipt of chemotherapy (OR = 2.43, 95%CI: 1.05-5.62, P = 0.038), and experience of severe treatment side effects (OR = 3.21, 95%CI: 1.89-5.45, P < 0.001, Table 4).

| Risk factor | Normal psychological health | Psychological problems | OR (95%CI) | χ2 value | P value |

| Demographic factors | |||||

| Age | |||||

| > 50 years | 106 (63.5) | 61 (51.7) | 1.00 (reference) | 4.12 | 0.042 |

| ≤ 50 years | 61 (36.5) | 57 (48.3) | 1.58 (1.02-2.44) | 0.041 | |

| Education level | |||||

| > High school | 117 (70.1) | 69 (58.5) | 1.00 (reference) | 5.34 | 0.021 |

| ≤ High school | 50 (29.9) | 49 (41.5) | 1.71 (1.09-2.69) | 0.020 | |

| Employment status | |||||

| Employed/retired | 140 (83.8) | 83 (70.3) | 1.00 (reference) | 8.23 | 0.004 |

| Unemployed | 18 (10.8) | 24 (20.3) | 2.14 (1.28-3.57) | 0.004 | |

| Other | 9 (5.4) | 11 (9.3) | 1.67 (0.89-3.12) | 0.112 | |

| Household income | |||||

| ≥ 5000 yuan/month | 91 (54.5) | 47 (39.8) | 1.00 (reference) | 7.89 | 0.005 |

| < 5000 yuan/month | 76 (45.5) | 71 (60.2) | 1.89 (1.21-2.95) | 0.005 | |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 137 (82.0) | 87 (73.7) | 1.00 (reference) | 3.21 | 0.073 |

| Unmarried/divorced/widowed | 30 (18.0) | 31 (26.3) | 1.63 (0.95-2.78) | 0.077 | |

| Residence | |||||

| Urban | 123 (73.7) | 80 (67.8) | 1.00 (reference) | 1.23 | 0.267 |

| Rural | 44 (26.3) | 38 (32.2) | 1.33 (0.81-2.18) | 0.259 | |

| Disease-related factors | |||||

| TNM stage | |||||

| Early stage (I-II) | 119 (71.3) | 66 (55.9) | 1.00 (reference) | 7.34 | 0.007 |

| Advanced stage (III-IV) | 48 (28.7) | 52 (44.1) | 2.31 (1.47-3.63) | < 0.001 | |

| Molecular subtype | |||||

| Luminal A/B | 129 (77.2) | 81 (68.6) | 1.00 (reference) | 8.92 | 0.030 |

| HER2-positive | 24 (14.4) | 21 (17.8) | 1.39 (0.75-2.58) | 0.291 | |

| Triple-negative | 14 (8.4) | 16 (13.6) | 2.67 (1.35-5.28) | 0.005 |

Multivariate logistic regression analysis, controlling for significant demographic, disease, and treatment variables, demonstrated that family dysfunction was an independent predictor of psychological morbidity. Overall family dysfunction showed the strongest predictive value (OR = 3.247, 95%CI: 1.832-5.756, P < 0.001), explaining 23.6% of the variance in psychological outcomes (Nagelkerke R2 = 0.236). Among specific family functioning dimensions, commu

| Variable | β coefficient | SE | Wald χ2 | OR (95%CI) | P value |

| Family functioning variables | |||||

| Overall family dysfunction | 1.178 | 0.291 | 16.42 | 3.247 (1.832-5.756) | < 0.001 |

| Communication dysfunction | 1.025 | 0.274 | 14.01 | 2.789 (1.623-4.791) | < 0.001 |

| Role dysfunction | 0.851 | 0.263 | 10.45 | 2.341 (1.389-3.947) | 0.001 |

| Affective responsiveness dysfunction | 0.638 | 0.252 | 6.42 | 1.892 (1.156-3.096) | 0.011 |

| Problem-solving dysfunction | 0.467 | 0.267 | 3.06 | 1.595 (0.946-2.691) | 0.080 |

| Control variables (final model) | |||||

| Age (≤ 50 years vs > 50 years) | 0.587 | 0.271 | 4.69 | 1.799 (1.059-3.057) | 0.024 |

| TNM stage (III-IV vs I-II) | 0.798 | 0.276 | 8.35 | 2.221 (1.293-3.815) | 0.003 |

| Treatment side effects (severe vs mild) | 0.689 | 0.264 | 6.81 | 1.992 (1.188-3.340) | 0.007 |

| Variables not retained in final model | |||||

| Education (≤ high school vs > high school) | 0.421 | 0.298 | 1.99 | 1.523 (0.849-2.734) | 0.158 |

| Employment (unemployed vs employed) | 0.487 | 0.345 | 1.99 | 1.627 (0.827-3.201) | 0.158 |

| Molecular subtype (triple-negative) | 0.567 | 0.398 | 2.03 | 1.763 (0.808-3.847) | 0.154 |

| Surgical method (mastectomy vs BCS) | 0.423 | 0.289 | 2.14 | 1.527 (0.866-2.690) | 0.143 |

A comprehensive risk prediction model was developed, incorporating family functioning assessment as a core component. The model achieved an area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of 0.798 (95%CI: 0.748-0.848), indicating good predictive accuracy. The optimal cutoff point identified patients with a > 60% probability of developing psychological problems with 78.5% sensitivity and 76.2% specificity. Risk stratification revealed that patients with family dysfunction had a 3.2-fold higher risk of developing clinically significant psychological symptoms compared to those with intact family functioning. The model demonstrated that early identification of family dysfunction could predict psychological morbidity with sufficient accuracy to guide clinical decision-making. Calibration analysis showed good agreement between predicted and observed psychological morbidity rates across risk categories (Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test: χ2 = 7.34, P = 0.501). These findings support the integration of family functioning assessment into routine clinical care for breast cancer patients, enabling healthcare providers to identify high-risk individuals and implement targeted family-centered interventions to prevent or mitigate psychological complications during the cancer journey (Figure 1B).

The theoretical underpinning of this research rests on family systems theory, which conceptualizes the family as an interconnected, dynamic system where changes in one member inevitably affect the entire unit[21]. This perspective challenges the traditional biomedical model that focuses primarily on individual pathology and instead emphasizes relational and contextual factors in health outcomes[22]. The McMaster Family Functioning Model, which forms the theoretical basis for our assessment approach, provides a comprehensive framework for understanding how families navigate crisis situations such as cancer diagnosis[23]. However, the application of Western-derived family functioning models to Chinese populations raises important questions about cultural validity[24]. Traditional Chinese family structures, with their emphasis on hierarchical relationships, filial piety, and collective decision-making, may not align perfectly with the individualistic assumptions underlying many family functioning theories[25]. The concept of “functional” communication, for instance, may differ significantly between cultures that value direct expression vs those that emphasize harmony preservation and indirect communication styles[26].

These findings have important implications for the design of culturally sensitive family interventions. Rather than imposing Western models of direct emotional expression, effective interventions for Chinese breast cancer patients should work within existing cultural frameworks to enhance family functioning. This might include: (1) Facilitating communication through culturally acceptable indirect methods, such as involving respected elders or using written communications; (2) Reframing open discussion of cancer-related concerns as fulfilling filial duty rather than violating family harmony; (3) Providing psychoeducation about how improved family communication during cancer care does not require abandoning cultural values but rather adapting them to meet the extraordinary demands of serious illness; and (4) Involving the entire family system in psychosocial interventions rather than focusing solely on individual patient therapy.

The practical implications extend to clinical assessment and screening as well. While the FAD demonstrates good psychometric properties in Chinese populations, clinicians should interpret elevated communication dysfunction scores not simply as family pathology but as potential indicators of cultural communication patterns that, under the stress of cancer, may insufficiently meet patients’ psychological needs. This nuanced interpretation allows for both cultural sensitivity and clinical utility, recognizing cultural diversity while identifying patients at risk for psychological complications who would benefit from enhanced family support. The field of psycho-oncology has undergone significant evolution since its emergence in the 1970s[27]. Early research focused primarily on individual psychological factors, gradually expanding to include social and environmental determinants of psychological adjustment to cancer[28]. The growing recognition of family-centered care represents a paradigm shift toward more holistic, systems-based approaches to cancer care[29].

This evolution reflects broader changes in healthcare philosophy, moving from paternalistic models toward patient- and family-centered care[30]. However, the implementation of family-centered approaches has been inconsistent, often limited by resource constraints, lack of validated assessment tools, and insufficient training among healthcare providers[31]. The present research contributes to this evolving landscape by providing empirical evidence for specific family factors that influence psychological outcomes. Research examining family functioning in medical contexts faces several inherent methodological challenges[32]. The complexity of family dynamics makes it difficult to isolate specific causal mechanisms, and the bidirectional nature of family relationships complicates the establishment of clear temporal sequences[33]. Families experiencing cancer may simultaneously exhibit both adaptive and maladaptive functioning patterns, making categorization problematic.

The retrospective design employed in this study, while pragmatic, introduces several limitations that must be acknowledged. Recall bias may affect participants’ reporting of family functioning, particularly when psychological symptoms are present. Additionally, the cross-sectional nature of family functioning assessment cannot capture the dynamic changes that occur throughout the cancer trajectory. Families may function well at diagnosis but deteriorate during treatment, or conversely, may develop increased cohesion and improved communication in response to the crisis. The Chinese cultural context significantly influences family functioning patterns and their health implications[34]. Traditional Confucian values emphasize family harmony, respect for authority, and collective well-being over individual needs[26]. These cultural factors may create unique stressors when families face a cancer diagnosis, particularly when treatment decisions require challenging traditional hierarchies or when economic burden threatens family stability.

The concept of “face” (mianzi) in Chinese culture may particularly impact communication patterns within families dealing with cancer[25]. Family members may avoid expressing concerns or negative emotions to preserve family har

The Chinese healthcare system context significantly influences family involvement in cancer care. Unlike Western systems, where patient autonomy is paramount, Chinese medical practice often involves families more directly in medi

These findings have broader implications for healthcare delivery models and provider training. The integration of family functioning assessment into routine oncology care requires systematic changes in clinical workflows, staff training, and resource allocation[29]. Healthcare providers need education about family systems concepts and skills for assessing and addressing family dysfunction[30]. Furthermore, the development of family-centered care models must consider the practical constraints of clinical settings, including time limitations, privacy concerns, and the complex logistics of involving multiple family members in care planning and delivery. The present research contributes to a growing body of evidence supporting the importance of family factors in cancer care outcomes, while highlighting the need for culturally sensitive approaches to family functioning assessment and intervention in diverse populations.

The evidence presented here establishes family dysfunction as a clinically significant and potentially modifiable risk factor for psychological morbidity in breast cancer patients, warranting integration of family functioning assessment into comprehensive cancer care protocols.

| 1. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 68522] [Article Influence: 13704.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (201)] |

| 2. | Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Parkin DM, Piñeros M, Znaor A, Bray F. Cancer statistics for the year 2020: An overview. Int J Cancer. 2021. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2411] [Cited by in RCA: 3300] [Article Influence: 660.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 3. | Lei S, Zheng R, Zhang S, Chen R, Wang S, Sun K, Zeng H, Wei W, He J. Breast cancer incidence and mortality in women in China: temporal trends and projections to 2030. Cancer Biol Med. 2021;18:900-909. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 30.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | DeSantis CE, Ma J, Gaudet MM, Newman LA, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Breast cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:438-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1500] [Cited by in RCA: 2079] [Article Influence: 297.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Allemani C, Matsuda T, Di Carlo V, Harewood R, Matz M, Nikšić M, Bonaventure A, Valkov M, Johnson CJ, Estève J, Ogunbiyi OJ, Azevedo E Silva G, Chen WQ, Eser S, Engholm G, Stiller CA, Monnereau A, Woods RR, Visser O, Lim GH, Aitken J, Weir HK, Coleman MP; CONCORD Working Group. Global surveillance of trends in cancer survival 2000-14 (CONCORD-3): analysis of individual records for 37 513 025 patients diagnosed with one of 18 cancers from 322 population-based registries in 71 countries. Lancet. 2018;391:1023-1075. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2711] [Cited by in RCA: 3686] [Article Influence: 460.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Zabora J, BrintzenhofeSzoc K, Curbow B, Hooker C, Piantadosi S. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology. 2001;10:19-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ganz PA, Yip CH, Gralow JR, Distelhorst SR, Albain KS, Andersen BL, Bevilacqua JL, de Azambuja E, El Saghir NS, Kaur R, McTiernan A, Partridge AH, Rowland JH, Singh-Carlson S, Vargo MM, Thompson B, Anderson BO. Supportive care after curative treatment for breast cancer (survivorship care): resource allocations in low- and middle-income countries. A Breast Health Global Initiative 2013 consensus statement. Breast. 2013;22:606-615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Burgess C, Cornelius V, Love S, Graham J, Richards M, Ramirez A. Depression and anxiety in women with early breast cancer: five year observational cohort study. BMJ. 2005;330:702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 823] [Cited by in RCA: 871] [Article Influence: 41.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mitchell AJ, Chan M, Bhatti H, Halton M, Grassi L, Johansen C, Meader N. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and adjustment disorder in oncological, haematological, and palliative-care settings: a meta-analysis of 94 interview-based studies. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12:160-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1351] [Cited by in RCA: 1585] [Article Influence: 105.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mehnert A, Brähler E, Faller H, Härter M, Keller M, Schulz H, Wegscheider K, Weis J, Boehncke A, Hund B, Reuter K, Richard M, Sehner S, Sommerfeldt S, Szalai C, Wittchen HU, Koch U. Four-week prevalence of mental disorders in patients with cancer across major tumor entities. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3540-3546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 532] [Cited by in RCA: 416] [Article Influence: 34.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Hartung TJ, Brähler E, Faller H, Härter M, Hinz A, Johansen C, Keller M, Koch U, Schulz H, Weis J, Mehnert A. The risk of being depressed is significantly higher in cancer patients than in the general population: Prevalence and severity of depressive symptoms across major cancer types. Eur J Cancer. 2017;72:46-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Abbey G, Thompson SB, Hickish T, Heathcote D. A meta-analysis of prevalence rates and moderating factors for cancer-related post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychooncology. 2015;24:371-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 152] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Spiegel D, Giese-Davis J. Depression and cancer: mechanisms and disease progression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:269-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 551] [Cited by in RCA: 546] [Article Influence: 23.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Lutgendorf SK, Sood AK, Anderson B, McGinn S, Maiseri H, Dao M, Sorosky JI, De Geest K, Ritchie J, Lubaroff DM. Social support, psychological distress, and natural killer cell activity in ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7105-7113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | DiMatteo MR, Lepper HS, Croghan TW. Depression is a risk factor for noncompliance with medical treatment: meta-analysis of the effects of anxiety and depression on patient adherence. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2101-2107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2682] [Cited by in RCA: 2801] [Article Influence: 107.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Epstein NB, Baldwin LM, Bishop DS. The McMaster Family Assessment Device. J Marital Fam Ther. 1983;9:171-180. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 17. | Miller IW, Ryan CE, Keitner GI, Bishop DS, Epstein NB. The McMaster Approach to Families: theory, assessment, treatment and research. J Fam Ther. 2000;22:168-189. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 18. | Byles J, Byrne C, Boyle MH, Offord DR. Ontario Child Health Study: reliability and validity of the general functioning subscale of the McMaster Family Assessment Device. Fam Process. 1988;27:97-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 618] [Cited by in RCA: 531] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Martire LM, Lustig AP, Schulz R, Miller GE, Helgeson VS. Is it beneficial to involve a family member? A meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for chronic illness. Health Psychol. 2004;23:599-611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 264] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hagedoorn M, Sanderman R, Bolks HN, Tuinstra J, Coyne JC. Distress in couples coping with cancer: a meta-analysis and critical review of role and gender effects. Psychol Bull. 2008;134:1-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 511] [Cited by in RCA: 537] [Article Influence: 29.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Calatrava M, Martins MV, Schweer-Collins M, Duch-Ceballos C, Rodríguez-González M. Differentiation of self: A scoping review of Bowen Family Systems Theory's core construct. Clin Psychol Rev. 2022;91:102101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196:129-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6292] [Cited by in RCA: 5508] [Article Influence: 112.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Tsamparli A, Petmeza I, McCarthy G, Adamis D. The Greek version of the McMaster Family Assessment Device. Psych J. 2018;7:122-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Hall GC, Ibaraki AY, Huang ER, Marti CN, Stice E. A Meta-Analysis of Cultural Adaptations of Psychological Interventions. Behav Ther. 2016;47:993-1014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 225] [Cited by in RCA: 308] [Article Influence: 30.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kirmayer LJ, Gomez-Carrillo A, Veissière S. Culture and depression in global mental health: An ecosocial approach to the phenomenology of psychiatric disorders. Soc Sci Med. 2017;183:163-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kim BK, Li LC, Ng GF. The Asian American values scale--multidimensional: development, reliability, and validity. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2005;11:187-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Holland JC. History of psycho-oncology: overcoming attitudinal and conceptual barriers. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:206-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Andersen BL. Biobehavioral outcomes following psychological interventions for cancer patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:590-610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Hsu JL, Chen A, Cruz-Hinojoza E, Dinh-Dang D, Roth-Johnson EA, Sato BK, Lo SM. Characterizing Biology Education Research: Perspectives from Practitioners and Scholars in the Field. J Microbiol Biol Educ. 2021;22:e00147-e00121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Epstein RM, Fiscella K, Lesser CS, Stange KC. Why the nation needs a policy push on patient-centered health care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:1489-1495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 508] [Cited by in RCA: 563] [Article Influence: 35.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Kissane DW, Love A, Hatton A, Bloch S, Smith G, Clarke DM, Miach P, Ikin J, Ranieri N, Snyder RD. Effect of cognitive-existential group therapy on survival in early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4255-4260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Northouse LL, Katapodi MC, Schafenacker AM, Weiss D. The impact of caregiving on the psychological well-being of family caregivers and cancer patients. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2012;28:236-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 282] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Long KA, Marsland AL. Family adjustment to childhood cancer: a systematic review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2011;14:57-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 281] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Wen KY, Gustafson DH, Hawkins RP, Brennan PF, Dinauer S, Johnson PR, Siegler T. Developing and validating a model to predict the success of an IHCS implementation: the Readiness for Implementation Model. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2010;17:707-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/