Published online Feb 19, 2026. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v16.i2.113124

Revised: October 8, 2025

Accepted: November 5, 2025

Published online: February 19, 2026

Processing time: 148 Days and 22.2 Hours

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) is an effective method for treating the motor sym

To construct a gradient boosting machine (GBM) risk model to predict the risk of mental complications such as depression, anxiety, and cognitive impairment in patients with PD after DBS surgery.

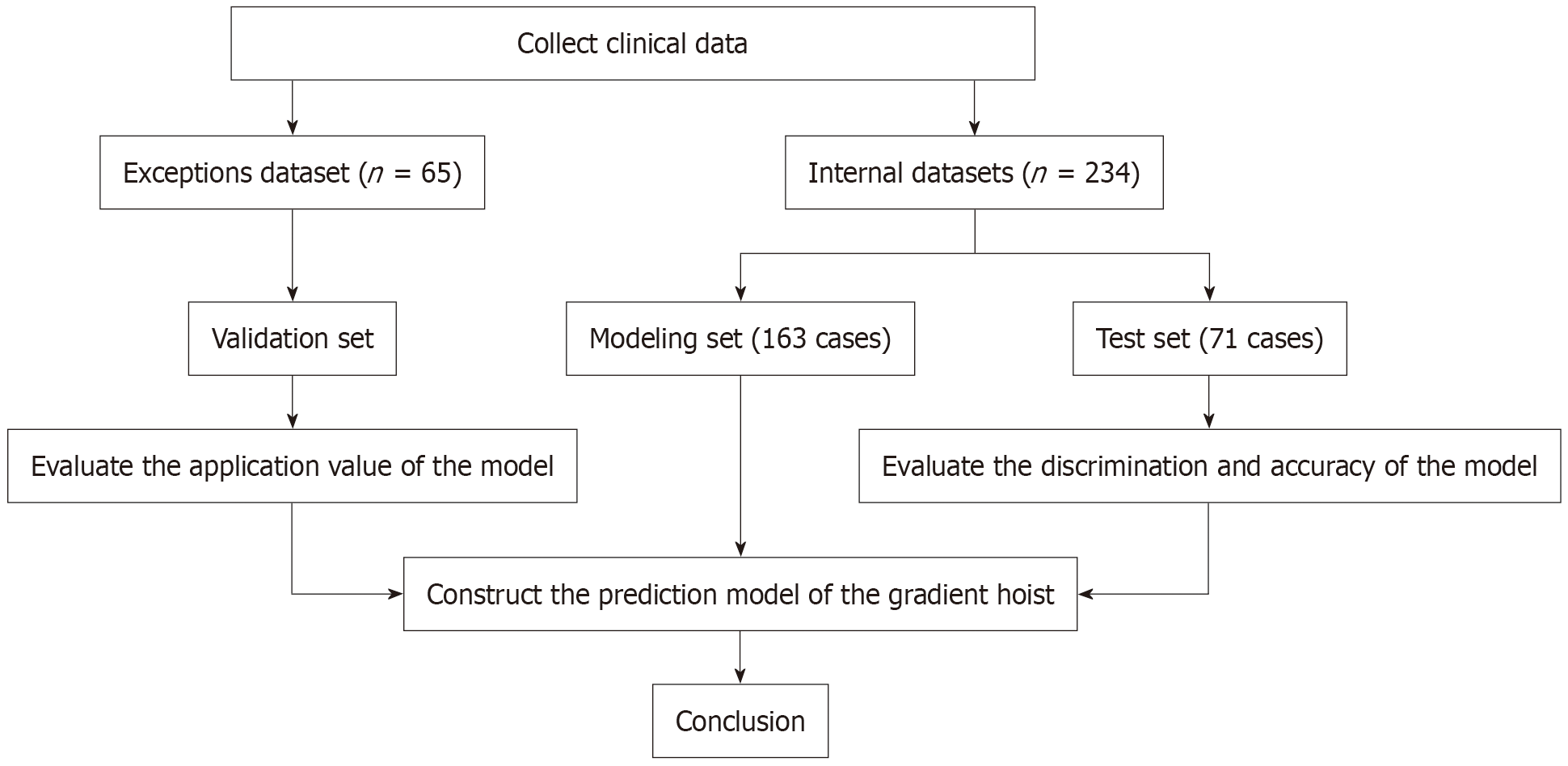

We retrospectively collected data on patients with PD treated at a top-tier hospital in China between June 2023 and December 2024. During this period, 234 cases were screened and analyzed, of which 70% were included in the modeling set and the remaining 30% in the test set. The modeling set was used to construct the risk prediction model, whereas the test set was used to validate the predictive per

In a cohort of 234 patients undergoing DBS, the incidence of psychiatric complications such as depression, anxiety, and cognitive impairment was 37.61%. Age, surgery duration, fasting time, family relationship health assessment scale scores, and unified PD rating scale III scores were identified as independent influencing factors. Based on these variables, the constructed GBM model demonstrated ex

The prediction model constructed based on the GBM algorithm has good predictive performance and can provide a reference for clinical medical staff to identify groups at high risk for mental complications such as depression, anxiety, cognitive impairment, and delirium after DBS.

Core Tip: This study developed a gradient boosting machine (GBM) model to predict psychiatric complications (depression, anxiety, cognitive impairment, and delirium) in patients with Parkinson’s disease after deep brain stimulation surgery. By analyzing data from 234 patients, the model identified five critical risk factors: Age, surgery duration, fasting time, Family Relationship Health Assessment Scale score, and motor symptom severity (Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale Part III score). These factors collectively explained 37.6% complication incidence. The GBM model achieved high predictive ac

- Citation: Liao S, Tang JW, Li Y. Gradient boosting machine model predicts psychiatric complications after deep brain stimulation in Parkinson’s disease. World J Psychiatry 2026; 16(2): 113124

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v16/i2/113124.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v16.i2.113124

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder. Epidemiological data show that the prevalence of the disease is approximately 0.3% in the general population[1]; however, it increases significantly to 1%-2% among the older po

Currently, the treatment of PD mainly relies on medication and surgical interventions, aiming to delay disease pro

However, the impact of DBS on psychiatric complications such as anxiety, depression, delirium, and cognitive dys

A retrospective observational study involving patients with PD who underwent DBS between June 2023 and December 2024 was conducted at a tertiary hospital in China. The patients were screened according to the following inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Age > 18 years, diagnosis of primary PD based on diagnostic criteria[11], Hoehn-Yahr stages 2-5; (2) Indication for DBS treatment, with bilateral electrode implantation and completed therapy; (3) Normal coagulation function; (4) Normal language, hearing, and communication abilities, capable of completing questionnaires; and (5) Complete clinical and follow-up data.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Patients with secondary Parkinsonism caused by primary brain diseases (e.g., cerebral hemorrhage, encephalitis); (2) Intracranial tumors; (3) Those undergoing only battery replacement or electrode adjustment procedures; (4) Comorbid essential tremor; (5) Immunodeficiency disorders; (6) Cerebral atrophy or Parkinson-plus syndromes; and (7) Severe psychiatric disorders (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder).

Two independent researchers retrieved and analyzed relevant literature materials through the system to determine the materials that needed to be collected, including: (1) General clinical data: Age, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, education level, swallowing ability, and Hoehn-Yahr stage; (2) Perioperative indicators: Neutrophils, lymphocytes, hemoglobin, white blood cells, serum albumin, C-reactive protein, operation time, anesthesia time, intraoperative blood loss, fasting time, and postoperative intracranial gas volume; and (3) Relevance scale: The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) was used to assess sleep quality, with scores ranging from 0 to 21. A total score of seven or higher indicated the presence of sleep problems, with higher scores corresponding to poorer sleep quality. Family relationship health was evaluated using the Family Relationship Health Assessment Scale (H-FRAT), which has a score range of 25 to 50, with higher scores reflecting healthier family dynamics. The quality of life in patients is measured using the 39-item Par

The outcome indicator of this study was the occurrence of mental complications such as anxiety, depression, cognitive dysfunction, and delirium after DBS surgery. Patients with any of the above conditions were considered to have pos

The study defined postoperative neuropsychiatric complications using the following criteria: (1) Within 3 days after surgery, patients showing new-onset or worsened depression/anxiety states, as indicated by increased HAMD or HAMA severity ratings [e.g., progression from “possible anxiety” (HAMA score 7-13) to “definite anxiety” (HAMA score ≥ 14), or from “normal” (HAMD score < 8) to “mild depression” (HAMD score 9-20)]; (2) Within 3 postoperative days, patients demonstrating cognitive decline based on MMSE rating reductions [e.g., transitioning from “normal/mild cognitive impairment” (MMSE > 18) to “moderate-severe cognitive impairment” (MMSE ≤ 18)]; and (3) Presence of delirium as identified by a 3-minute diagnostic interview for confusion assessment method-defined delirium, an assessment tool adapted from the confusion assessment method, that combines structured patient interviews and behavioral observations to evaluate delirium status. All assessments were conducted by trained clinicians using standardized protocols.

The GBM model is constructed using the ‘gbm’ package in R. In the ‘gbm’ package, decision trees are used as base learners. The key parameters were as follows: The response variable (distribution) was binary (Bernoulli), the number of boosting trees was set to 2000, the learning rate (shrinkage) was 0.01, and a 10-fold cross-validation (cross-validation folds = 10) was used to select the optimal number of boosting trees.

Data storage and management were performed using Excel 2016, while statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 23.0 and R version 4.0.3. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD and compared using t-tests. Categorical variables were presented as proportions (%) and analyzed using χ2 tests or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. The least absolute contraction and selection operator (LASSO) method was used to reduce the dimensions of the data, and logistic regression analysis was used to identify risk factors. The predictive performance of the model was validated in the modelling and test sets using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) and calibration curves, respectively. Decision curve analysis (DCA) was used to evaluate the clinical utility of the model. Statistical significance was defined as a two-sided P value < 0.05.

From January 2023 to December 2024, we screened 234 cases for the construction and training of the gradient lift pre

In a dataset of 234 internal cases, 88 patients (37.61%) with PD experienced mental complications within 3 days after DBS. Among them, 27 (30.68%) experienced depression or an exacerbation of depression,18 cases (20.45%) experienced anxiety or an exacerbation of anxiety, 15 cases (17.05%) had a decline in cognitive function rating, and 28 (31.82%) showed sym

In Table 1, compared with those of patients in the non-complication group, patients in the complication group were older and had a higher proportion of hypertension and diabetes history (P < 0.05).

| Items | Complication group (69 cases) | Non-complication group (94 cases) | t/χ2 value | P value |

| Onset age (year) | 56.28 ± 6.99 | 53.96 ± 7.10 | 2.073 | 0.040 |

| Sex | 1.184 | 0.281 | ||

| Man | 36 (52.17) | 57 (60.64) | ||

| Woman | 33 (47.83) | 37 (39.36) | ||

| BMI (kg/m²) | 22.47 ± 1.98 | 23.02 ± 2.19 | 1.662 | 0.099 |

| The course of Parkinson’s disease | 8.01 ± 3.56 | 7.23 ± 2.97 | 1.521 | 0.130 |

| Education | 0.549 | 0.459 | ||

| Junior high school and below | 59 (85.51) | 84 (89.36) | ||

| High school and above | 10 (14.49) | 10 (10.64) | ||

| Hypertension history | 35 (50.72) | 26 (27.66) | 9.039 | 0.003 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 33 (47.83) | 24 (25.53) | 8.697 | 0.003 |

| Swallowing disorder | 28 (40.58) | 26 (27.66) | 2.998 | 0.083 |

| H-Y stage | 1.785 | 0.074 | ||

| 3 | 52 (75.36) | 81 (86.17) | ||

| 4 | 16 (23.19) | 13 (13.83) | ||

| 5 | 1 (1.45) | 0 (0.00) |

As shown in Table 2, compared with those of patients in the non-complication group, patients in the complication group had a longer operation time, longer food deprivation time, and higher intracranial gas volume after surgery (P < 0.05).

| Items | Complication group (69 cases) | Non-complication group (94 cases) | t value | P value |

| NLR | 2.41 ± 1.79 | 2.58 ± 2.06 | 0.542 | 0.589 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 136.62 ± 15.05 | 138.85 ± 12.72 | 1.022 | 0.308 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 42.73 ± 6.75 | 42.35 ± 5.79 | 0.389 | 0.698 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 38.71 ± 12.61 | 39.37 ± 14.07 | 0.310 | 0.757 |

| Operation time (minute) | 267.36 ± 32.94 | 245.63 ± 32.57 | 4.189 | < 0.001 |

| Anesthesia time (minute) | 288.61 ± 57.79 | 282.51 ± 51.46 | 0.709 | 0.479 |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 54.06 ± 13.43 | 53.40 ± 18.87 | 0.246 | 0.806 |

| Fasting time (hour) | 8.87 ± 0.87 | 7.84 ± 0.88 | 7.423 | < 0.001 |

| postoperative intracranial gas volume (mm3) | 9.90 ± 3.46 | 7.42 ± 2.74 | 4.912 | < 0.001 |

As shown in Table 3, the PSQI, PDQ-39, and UPDRS III scores of patients in the complication group were all higher than that of those in the non-complication group, whereas the H-FRAT score was lower than that in the non-complication group (P < 0.05).

| Items | Complication group (69 cases) | Non-complication group (94 cases) | t value | P value |

| PSQI score | 10.57 ± 1.98 | 8.62 ± 2.32 | 5.630 | < 0.001 |

| H-FRAT score | 28.94 ± 3.15 | 32.86 ± 4.81 | 6.274 | < 0.001 |

| PDQ-39 score | 74.81 ± 8.97 | 70.78 ± 11.42 | 2.434 | 0.016 |

| UPDRS III score | 42.65 ± 5.00 | 38.09 ± 4.65 | 6.002 | < 0.001 |

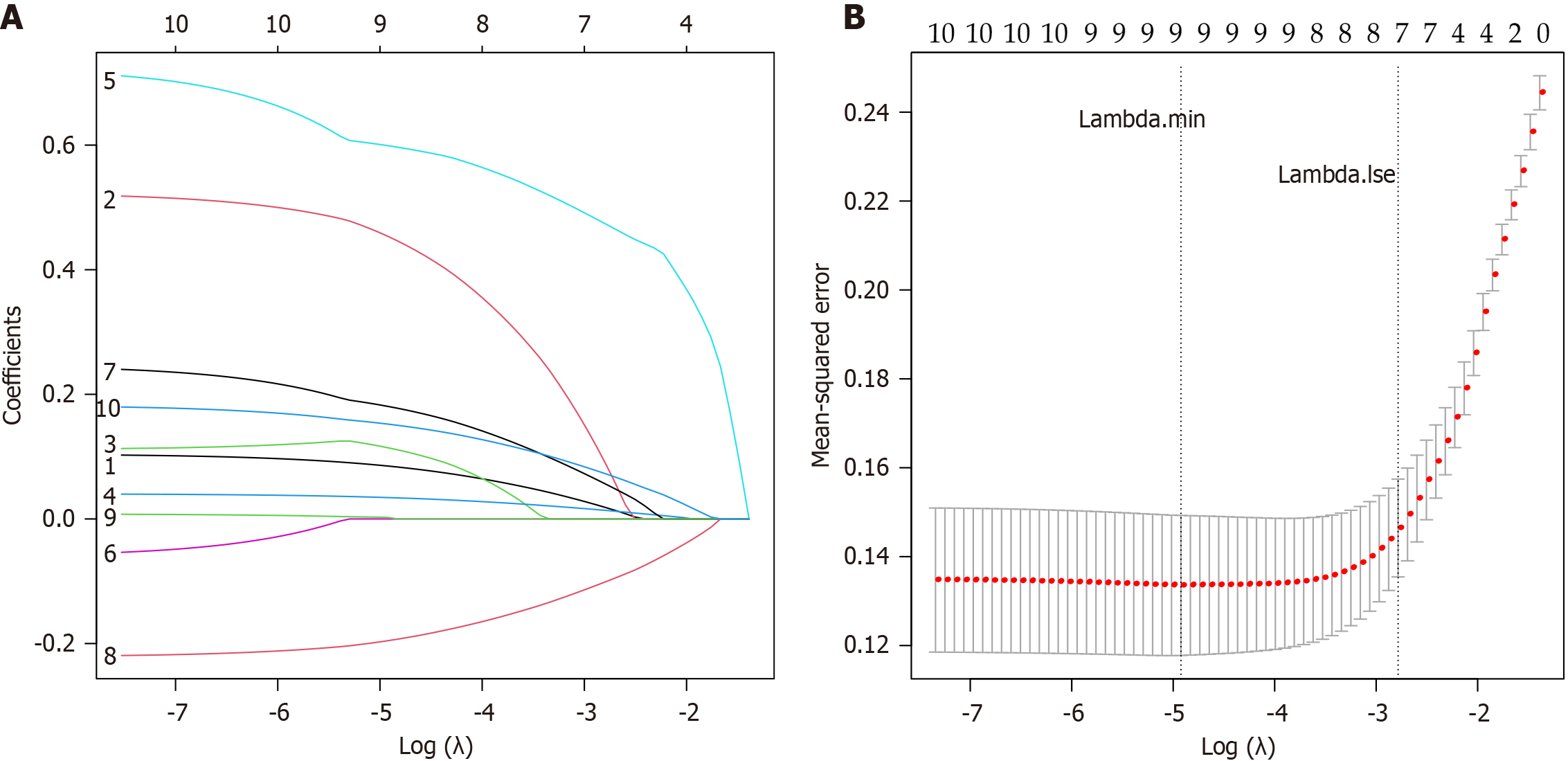

LASSO regression analysis was performed on the eight variables with statistically significant differences, as shown in Tables 1, 2, and 3. The final parameter λ was determined through cross-validation, and the λ value corresponding to the maximum value within one standard error of the minimum mean squared error was chosen as the optimal parameter. In this study, the Lambda.lse was 0.062. As shown in Figure 2, seven independent variables (age, history of hypertension, operation time, fasting time, PSQI score, H-FRAT score, and UPDRS III scores) were selected from the 10 variables to con

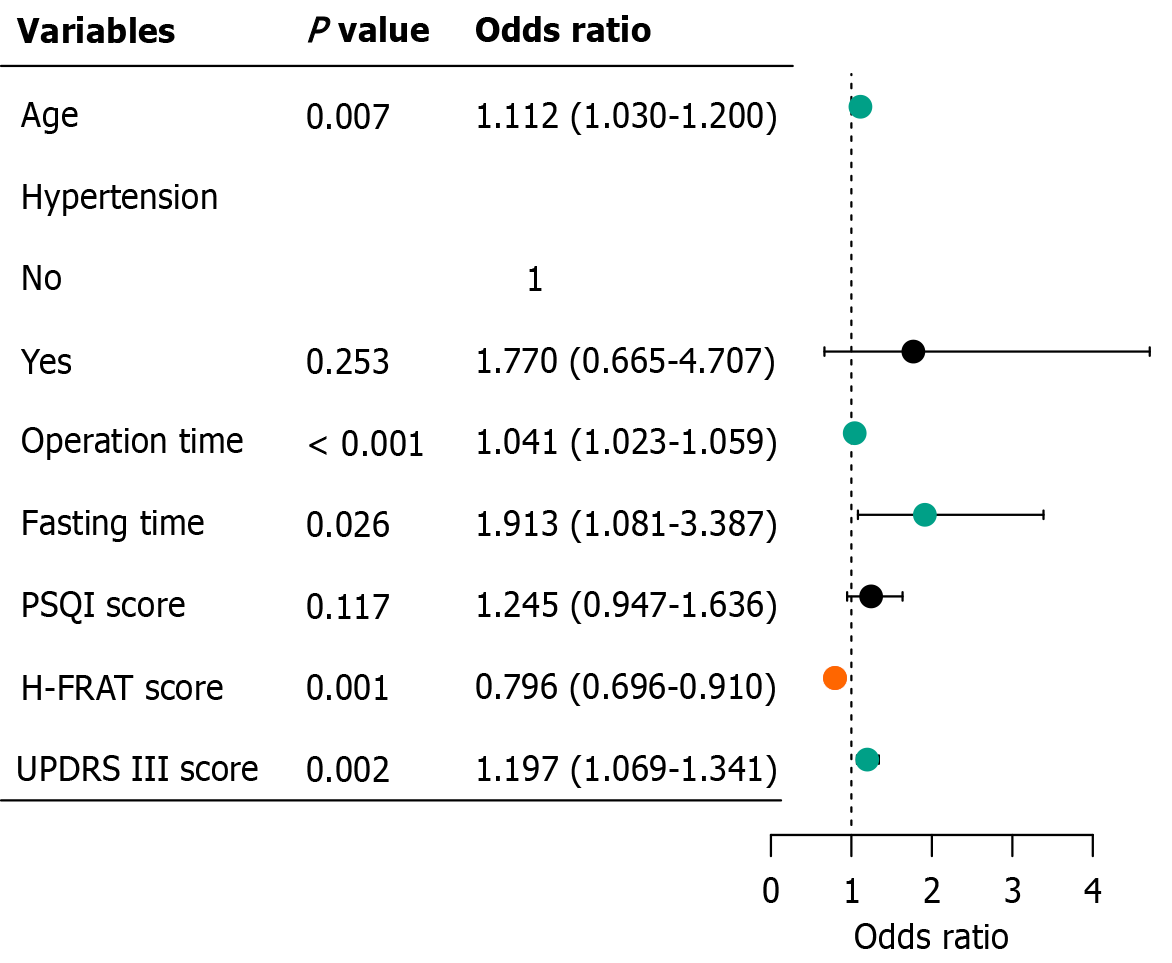

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed on the aforementioned seven variables, and five variables with statistical significance (P < 0.05) were selected: Age, operation time, fasting time, H-FRAT score, and UPDRS III score (Figure 3).

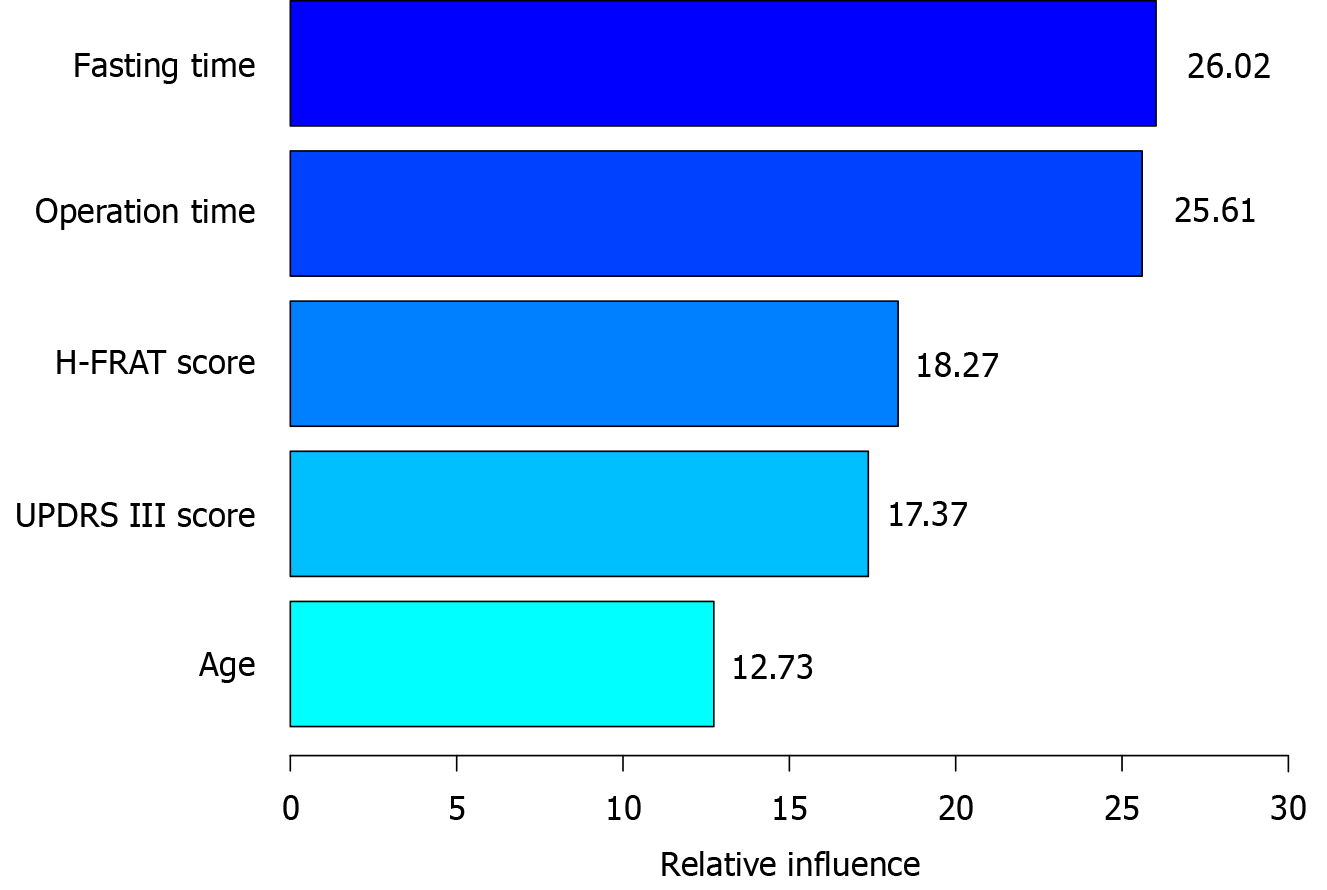

The GBM model ranked the important variables as follows: Fasting time (26.02 points), operation time (25.61 points), H-FRAT score (18.27 points), UPDRS III score (17.37 points) and age (12.73 points), as shown in Figure 4.

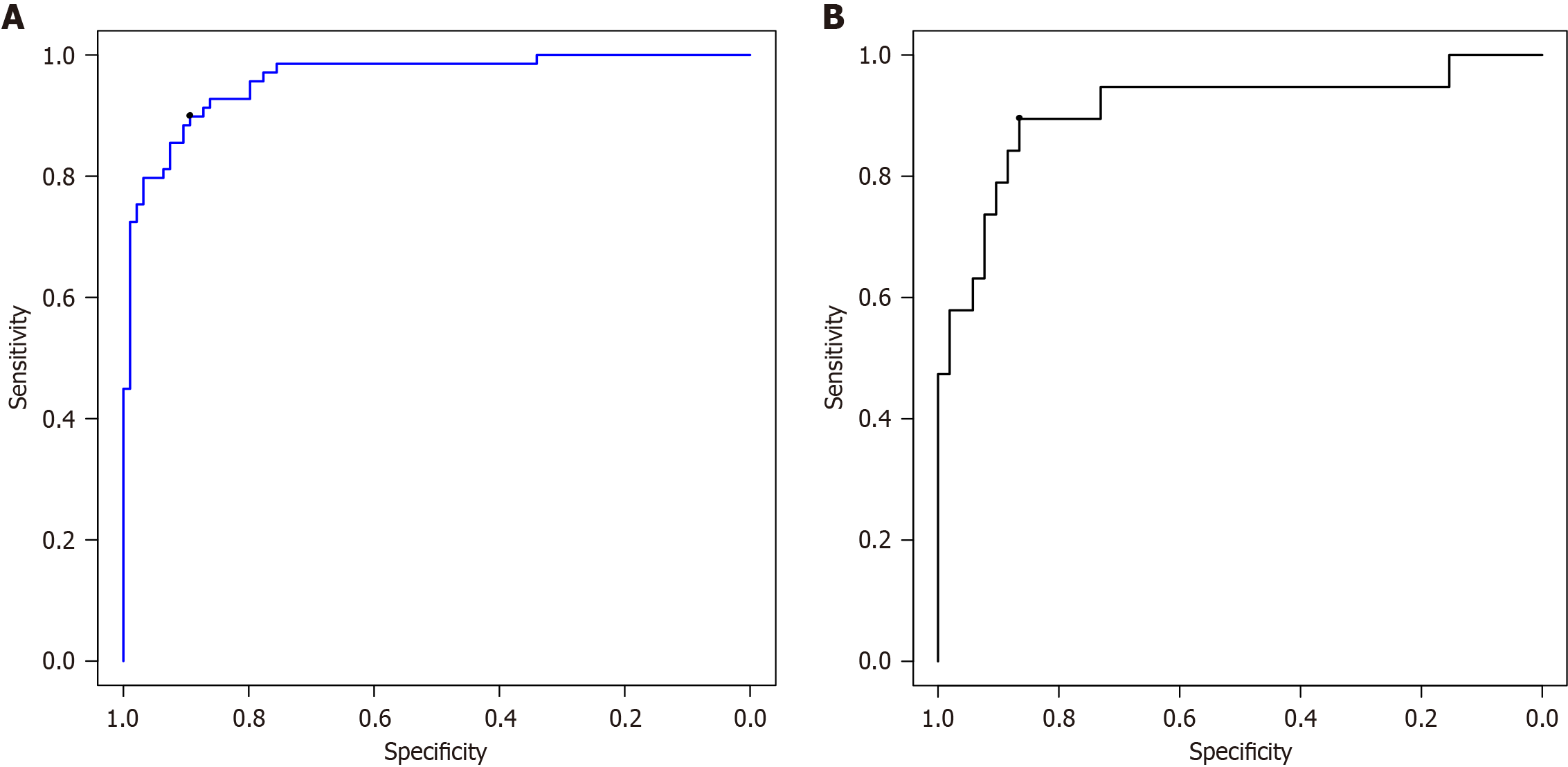

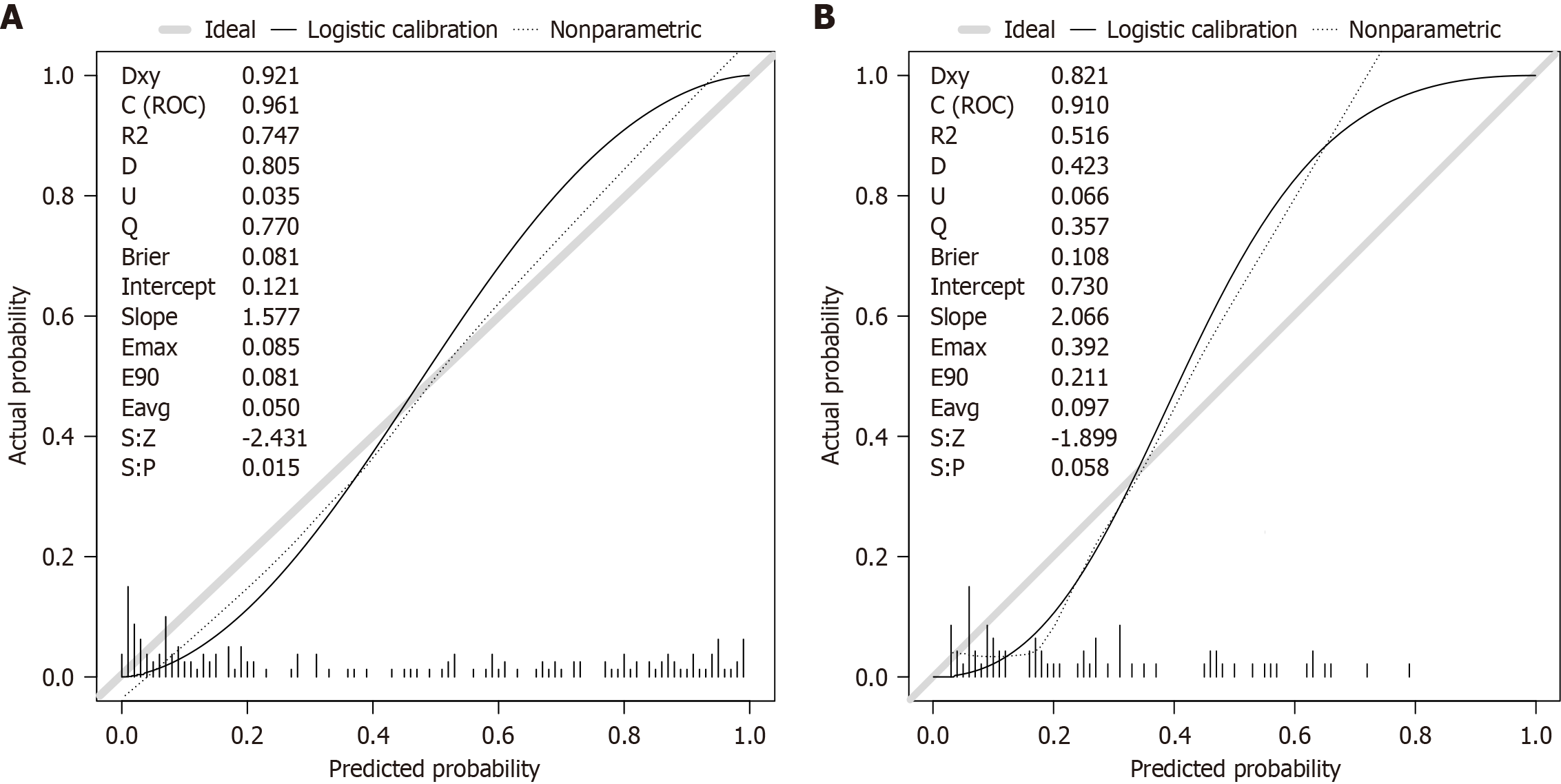

The ROC curve showed the area under the curve (AUC) for the GBM model in predicting patient prognosis, with the modeling set at 0.962 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.935-0.988], the test set at 0.917 (95%CI: 0.828-1.000), see Figure 5. The prediction accuracies of the modeling and test sets were 90.2% and 87.3%, respectively. The calibration curve showed good consistency between the values predicted by the GBM model and the actual observed values, indicating that the model can predict the actual probabilities relatively well, as shown in Figure 6. The Brier score for the modeling set was 0.081 and that for the test set was 0.108.

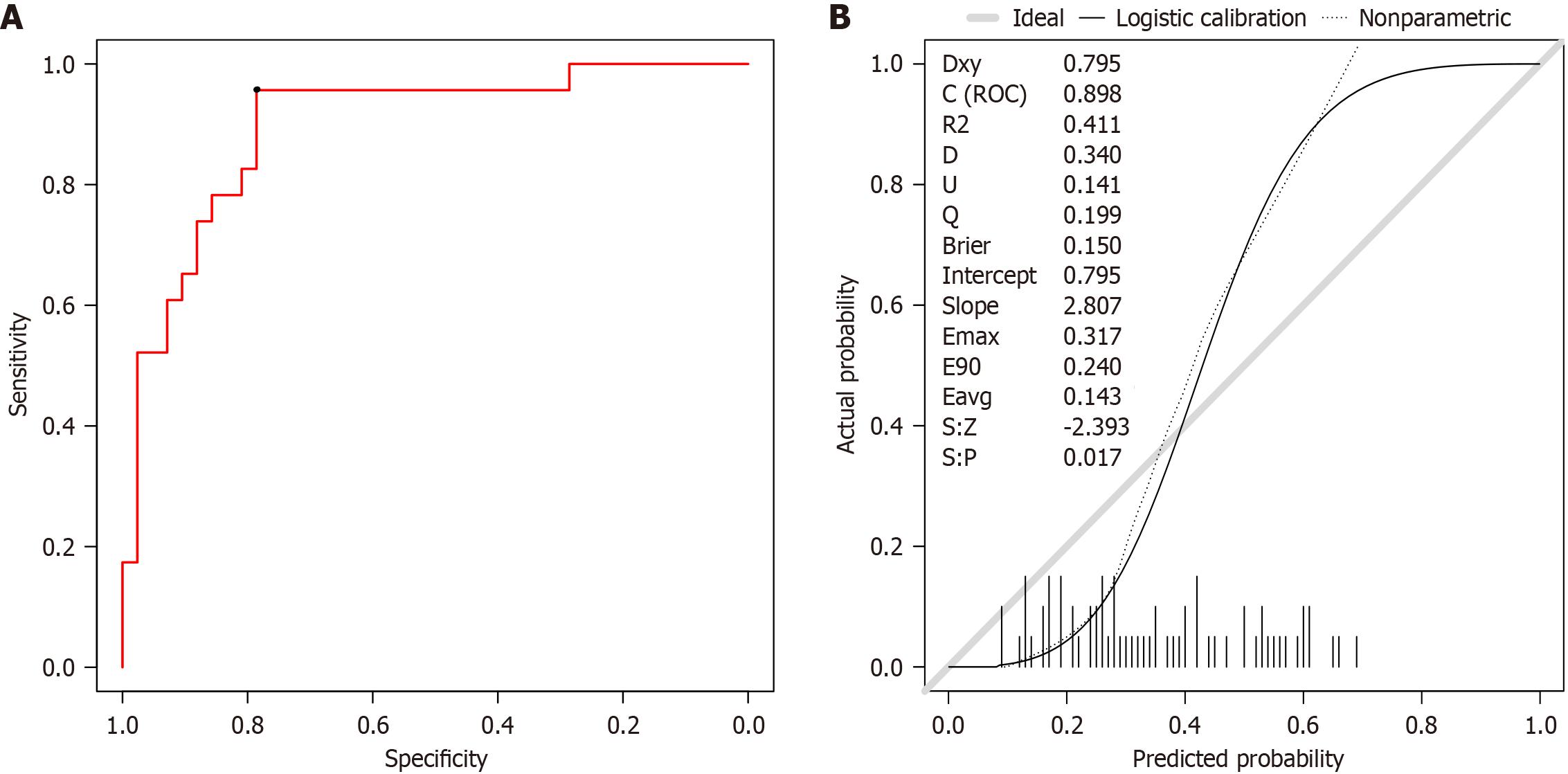

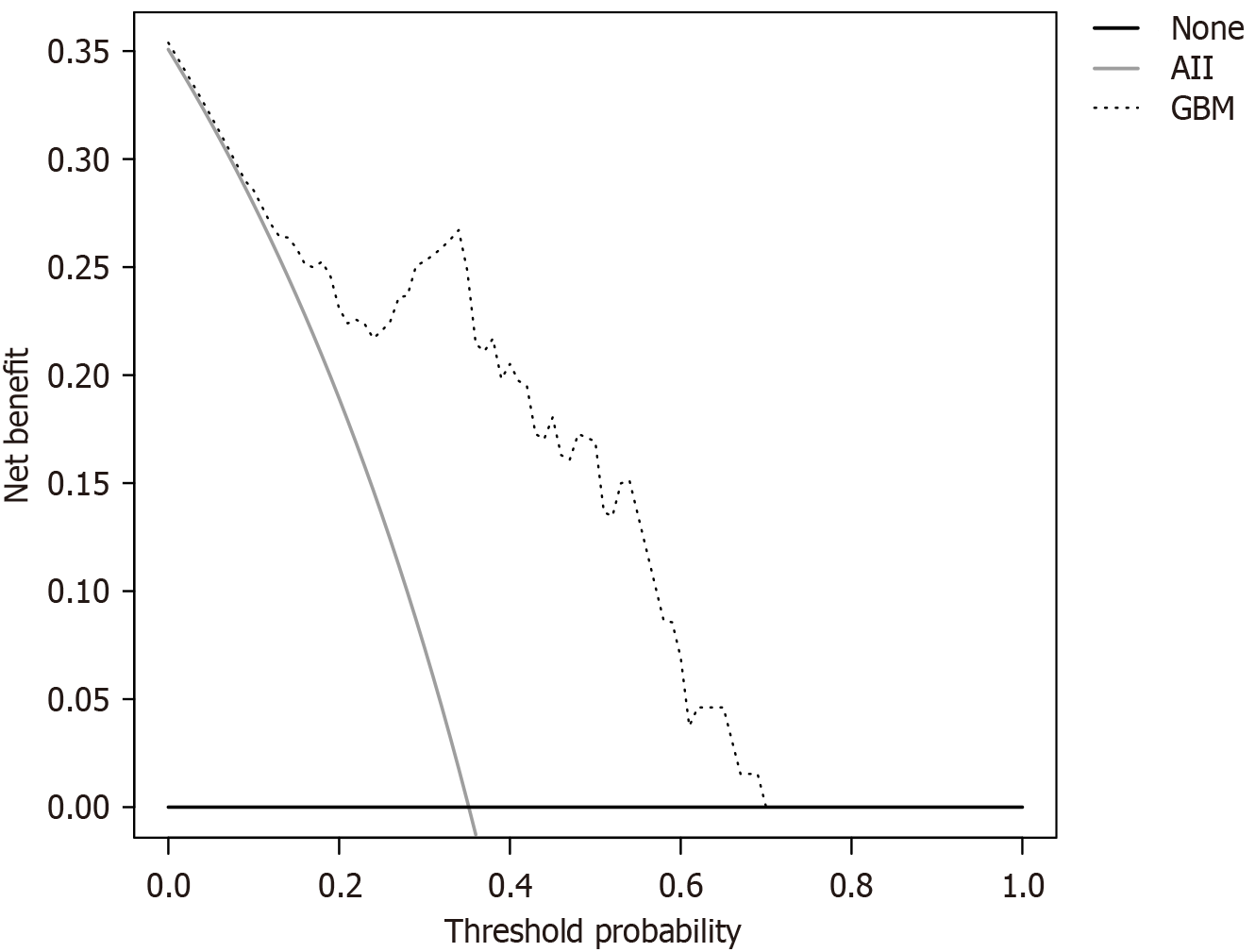

A total of 65 patients with PD using the model for diagnosis were predicted. The ROC curve showed that the accuracy of the prediction was 80.0%, the sensitivity was 95.7%, the specificity was 78.6%, and the AUC was 0.896 (95%CI: 0.818-0.978), as shown in Figure 7A. The calibration curve showed good consistency between the predicted values of the GBM and the actual observed values. The model can predict the actual probability well, and the Brier value was 0.081, as shown in Figure 7B. The DCA curve showed that the model had the best clinical benefits and applicability when the threshold was 0.09 and 0.70, as shown in Figure 8.

With increasing health awareness and advances in medical technology, the diagnosis and treatment of PD have sig

Our research shows that neuropsychiatric complications such as depression, anxiety, cognitive impairment, and de

Two critical perioperative factors, the surgical duration and fasting time, warrant special attention. Prolonged surgical time not only increases the physiological burden but may also exacerbate postoperative cognitive impairment and emotional instability due to cerebral overstimulation. Reportedly, extended anesthesia disrupts neurotransmitter balance, significantly elevating the risk of delirium and anxiety symptoms[26]. Regarding fasting management, although en

An important finding of this study was the significant negative correlation between the H-FRAT scores (reflecting family relationship quality) and the risk of postoperative psychiatric complications. The data showed that patients with higher H-FRAT scores had significantly lower incidences of postoperative depression and anxiety. This association can be explained through three mechanisms. First, healthy family relationships provide crucial emotional support that helps maintain psychological stability during recovery[29]. Second, family support mitigates stress responses and reduces anxiety/depression symptoms[30]. Most importantly, close family bonds facilitate better adaptation to the postoperative physical and psychological changes[31]. When patients feel understood and cared for by family members, their emotional regulation and psychological resilience are significantly enhanced. This finding has important clinical implications, suggesting that family support system evaluations should be incorporated into preoperative assessments, and targeted family-based interventions should be considered to optimize surgical outcomes.

Furthermore, this study confirmed preoperative UPDRS III scores as an independent risk factor for postoperative neuropsychiatric complications. As the gold standard for assessing the severity of motor symptoms in Parkinson’s, elevated UPDRS III scores indicate significant premotor dysfunction. This impairment affects mental health through two pathways. Directly, severe motor limitations reduce daily activity capacity and quality of life, thereby predisposing patients to depressive and anxious symptoms[32]. Indirectly, patients with poor baseline motor function often develop pessimistic expectations regarding surgical outcomes, which amplify anxiety during postoperative recovery. Notably, these patients undergo surgery with greater psychological vulnerability, which makes them more susceptible to emo

Machine learning (ML) technologies have demonstrated significant advantages in disease prediction by uncovering hidden patterns within vast clinical datasets, enabling the precise identification of high-risk patient populations and supporting targeted clinical interventions. ML has achieved groundbreaking application in DBS for PD, advancing early diagnosis[32], treatment response prediction[33], and personalized medicine[34]. Watts et al[34] developed a deep reinforcement learning (DRL)-based model that leveraged real-time motor fluctuation data from wearable sensors to predict the optimal medication timing and dosage. This model generates dynamic treatment plans that maximize symptom relief. The results demonstrated that the DRL-derived regimen significantly outperformed the traditional static treatment plans, highlighting its potential to enhance medical decision-making, particularly in chronic disease man

In clinical practice, when patients with PD are treated with DBS, the GBM model constructed in this study can be applied in the following steps to predict the risk of postoperative mental complications and to formulate management strategies. First, the preoperative assessment collects key variables such as the patient’s age, operation time, fasting time, H-FRAT score, and UPDRS III score, and inputs them into the GBM model to calculate the risk score. For high-risk patients (such as those with advanced age, long operation time, long fasting time, low H-FRAT score, and high UPDRS III score), it is recommended to provide family relationship counseling before the operation, optimize perioperative management, and shorten the operation and fasting times. Second, postoperative monitoring: Increase the monitoring frequency for high-risk patients after the operation; Assess HAMA, HAMD, and MMSE scores daily; and promptly identify and handle mental complications. Third, the decision support integrates the GBM model into the hospital information system, develops a clinical decision support system, automatically assesses risk, and provides suggestions before the operation. Medical staff can formulate personalized plans based on this information and carefully explain the prediction results to patients and their families. Through these steps, the GBM model can provide personalized preoperative risk assessments and postoperative intervention suggestions for patients with PD, thereby improving treatment outcomes and quality of life.

This study has some methodological limitations: (1) The retrospective study design may lead to information bias during the data collection process, particularly regarding the completeness and accuracy of clinical indicators. This finding needs to be validated through well-designed prospective cohort studies; (2) The model was constructed based solely on data from a single tertiary medical center. Although the internal validation demonstrated good performance, the lack of multi-center external validation data means that the model’s applicability, particularly in primary hospitals with different medical resource configurations, still requires further evaluation; and (3) Although the GBM model could handle mul

Patients with PD who undergo DBS have a higher incidence of neuropsychiatric complications. Age, operation time, fasting time, H-FRAT score, and UPDRS III score were the independent risk factors. The GBM model incorporating these predictors exhibited excellent discrimination and clinical utility, achieving 80.0% accuracy in preoperative risk stratification.

| 1. | Simon DK, Tanner CM, Brundin P. Parkinson Disease Epidemiology, Pathology, Genetics, and Pathophysiology. Clin Geriatr Med. 2020;36:1-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 560] [Cited by in RCA: 680] [Article Influence: 113.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tysnes OB, Storstein A. Epidemiology of Parkinson's disease. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2017;124:901-905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1008] [Cited by in RCA: 1566] [Article Influence: 174.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rajan S, Kaas B. Parkinson's Disease: Risk Factor Modification and Prevention. Semin Neurol. 2022;42:626-638. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Li G, Ma J, Cui S, He Y, Xiao Q, Liu J, Chen S. Parkinson's disease in China: a forty-year growing track of bedside work. Transl Neurodegener. 2019;8:22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hariz M, Blomstedt P. Deep brain stimulation for Parkinson's disease. J Intern Med. 2022;292:764-778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 30.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Guo S, Li J, Zhang Y, Li Y, Zhuang P. Optimal target localisation and eight-year outcome for subthalamic stimulation in patients with Parkinson's disease. Br J Neurosurg. 2021;35:151-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Brandmeir NJ, Murray A, Cheyuo C, Ferari C, Rezai AR. Deep Brain Stimulation for Multiple Sclerosis Tremor: A Meta-Analysis. Neuromodulation. 2020;23:463-468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Paim Strapasson AC, Martins Antunes ÁC, Petry Oppitz P, Dalsin M, de Mello Rieder CR. Postoperative Confusion in Patients with Parkinson Disease Undergoing Deep Brain Stimulation of the Subthalamic Nucleus. World Neurosurg. 2019;125:e966-e971. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Couto MI, Monteiro A, Oliveira A, Lunet N, Massano J. Depression and anxiety following deep brain stimulation in Parkinson's disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Med Port. 2014;27:372-382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sauerbier A, Herberg J, Stopic V, Loehrer PA, Ashkan K, Rizos A, Jost ST, Petry-Schmelzer JN, Gronostay A, Schneider C, Visser-Vandewalle V, Evans J, Nimsky C, Fink GR, Antonini A, Martinez-Martin P, Silverdale M, Weintraub D, Schrag A, Ray Chaudhuri K, Timmermann L, Dafsari HS; EUROPAR, the German Parkinson Society Non-motor Symptoms Study Group, and the International Parkinson and Movement Disorders Society Non-Motor Parkinson’s Disease Study Group. Predictors of short-term anxiety outcome in subthalamic stimulation for Parkinson's disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2024;10:114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Natekin A, Knoll A. Gradient boosting machines, a tutorial. Front Neurorobot. 2013;7:21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1236] [Cited by in RCA: 888] [Article Influence: 68.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Berg D, Lang AE, Postuma RB, Maetzler W, Deuschl G, Gasser T, Siderowf A, Schapira AH, Oertel W, Obeso JA, Olanow CW, Poewe W, Stern M. Changing the research criteria for the diagnosis of Parkinson's disease: obstacles and opportunities. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:514-524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Artusi CA, Rinaldi D, Balestrino R, Lopiano L. Deep brain stimulation for atypical parkinsonism: A systematic review on efficacy and safety. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2022;96:109-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wu W, Gong S, Wang S, Lei W, Yuan L, Wu W, Qiu J, Sun W, Luan G, Zhu M, Wang X, Liang G, Tao Y. Safety and efficiency of deep brain stimulation in the elderly patients with Parkinson's disease. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2024;30:e14899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chang B, Ni C, Mei J, Xiong C, Chen P, Jiang M, Niu C. Nomogram for Predicting Depression Improvement after Deep Brain Stimulation for Parkinson's Disease. Brain Sci. 2022;12:841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zhang F, Wang F, Li CH, Wang JW, Han CL, Fan SY, Gao DM, Xing YJ, Yang C, Zhang JG, Meng FG. Subthalamic nucleus-deep brain stimulation improves autonomic dysfunctions in Parkinson's disease. BMC Neurol. 2022;22:124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Rughani AI, Hodaie M, Lozano AM. Acute complications of movement disorders surgery: effects of age and comorbidities. Mov Disord. 2013;28:1661-1667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Birchall EL, Walker HC, Cutter G, Guthrie S, Joop A, Memon RA, Watts RL, Standaert DG, Amara AW. The effect of unilateral subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation on depression in Parkinson's disease. Brain Stimul. 2017;10:651-656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Zhang F, Wang F, Xing YJ, Yang MM, Wang JW, Li CH, Han CL, Fan SY, Gao DM, Yang C, Zhang JG, Meng FG. Correlation between Electrode Location and Anxiety Depression of Subthalamic Nucleus Deep Brain Stimulation in Parkinson's Disease. Brain Sci. 2022;12:755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ishihara A, Tanaka S, Ueno M, Iida H, Kaibori M, Nomi T, Hirokawa F, Ikoma H, Nakai T, Eguchi H, Shinkawa H, Hayami S, Maehira H, Shibata T, Kubo S. Preoperative Risk Assessment for Delirium After Hepatic Resection in the Elderly: a Prospective Multicenter Study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2021;25:134-144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Jones JD, Orozco T, Bowers D, Hu W, Jabarkheel Z, Chiu S, Ramirez-Zamora A, Foote K, Okun MS, Wagle Shukla A. Cognitive Outcomes for Essential Tremor Patients Selected for Thalamic Deep Brain Stimulation Surgery Through Interdisciplinary Evaluations. Front Hum Neurosci. 2020;14:578348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Terry RD, DeTeresa R, Hansen LA. Neocortical cell counts in normal human adult aging. Ann Neurol. 1987;21:530-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 501] [Cited by in RCA: 477] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zwirner J, Möbius D, Bechmann I, Arendt T, Hoffmann KT, Jäger C, Lobsien D, Möbius R, Planitzer U, Winkler D, Morawski M, Hammer N. Subthalamic nucleus volumes are highly consistent but decrease age-dependently-a combined magnetic resonance imaging and stereology approach in humans. Hum Brain Mapp. 2017;38:909-922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Darmani G, Drummond NM, Ramezanpour H, Saha U, Hoque T, Udupa K, Sarica C, Zeng K, Cortez Grippe T, Nankoo JF, Bergmann TO, Hodaie M, Kalia SK, Lozano AM, Hutchison WD, Fasano A, Chen R. Long-Term Recording of Subthalamic Aperiodic Activities and Beta Bursts in Parkinson's Disease. Mov Disord. 2023;38:232-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Liu J, Li J, Wang J, Zhang M, Han S, Du Y. Associated factors for postoperative delirium following major abdominal surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2023;38:e5942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Radtke FM, Franck M, MacGuill M, Seeling M, Lütz A, Westhoff S, Neumann U, Wernecke KD, Spies CD. Duration of fluid fasting and choice of analgesic are modifiable factors for early postoperative delirium. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2010;27:411-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Li Y, Lu Q, Wang B, Tang W, Fan L, Li D. Preoperative Fasting Times for Patients Undergoing Elective Surgery at a Pediatric Hospital in Shanghai: The Big Evidence-Practice Gap. J Perianesth Nurs. 2021;36:559-563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Koljack CE, Miyasaki J, Prizer LP, Katz M, Galifianakis N, Sillau SH, Kluger BM. Predictors of Spiritual Well-Being in Family Caregivers for Individuals with Parkinson's Disease. J Palliat Med. 2022;25:606-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Zhao L, Xu F, Zheng X, Xu Z, Osten B, Ji K, Ding S, Liu G, Yang S, Chen R. Mediation role of anxiety on social support and depression among diabetic patients in elderly caring social organizations in China during COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2023;23:790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Puga F, Wang D, Rafford M, Poe A, Pickering CEZ. The relationship between daily stressors, social support, depression and anxiety among dementia family caregivers: a micro-longitudinal study. Aging Ment Health. 2023;27:1291-1299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Cui SS, Du JJ, Fu R, Lin YQ, Huang P, He YC, Gao C, Wang HL, Chen SD. Prevalence and risk factors for depression and anxiety in Chinese patients with Parkinson disease. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17:270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Mei J, Desrosiers C, Frasnelli J. Machine Learning for the Diagnosis of Parkinson's Disease: A Review of Literature. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021;13:633752. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 26.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Belić M, Bobić V, Badža M, Šolaja N, Đurić-Jovičić M, Kostić VS. Artificial intelligence for assisting diagnostics and assessment of Parkinson's disease-A review. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2019;184:105442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Watts J, Khojandi A, Vasudevan R, Ramdhani R. Optimizing Individualized Treatment Planning for Parkinson's Disease Using Deep Reinforcement Learning. Annu Int Conf IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2020;2020:5406-5409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/