Published online Jan 19, 2026. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v16.i1.111812

Revised: September 14, 2025

Accepted: October 30, 2025

Published online: January 19, 2026

Processing time: 146 Days and 22.1 Hours

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients face significant psychological challenges alongside physical symptoms, necessitating a comprehensive understanding of how psychological vulnerability and adaptation patterns evolve throughout the disease course. This review examined 95 studies (2000-2025) from PubMed, Web of Science, and CNKI databases including longitudinal cohorts, randomized controlled trials, and mixed-methods research, to characterize the complex inter

Core Tip: This review identifies three distinct psychological vulnerability trajectories in rheumatoid arthritis patients, with early intervention within 3-6 months post-diagnosis reducing depression incidence by 42% and maintaining benefits for 24-36 months. Different psychological interventions demonstrate complementary therapeutic advantages: Cognitive behavioral therapy excels for depression treatment, mindfulness-based approaches optimize pain acceptance, and peer support facilitates meaning reconstruction.

- Citation: Chen XM, Cheng X, Wu W. Dynamic psychological vulnerability and adaptation in rheumatoid arthritis: Trajectories, predictors, and interventions. World J Psychiatry 2026; 16(1): 111812

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v16/i1/111812.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v16.i1.111812

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a common chronic autoimmune disease with a global prevalence of approximately 0.5%-1% and a prevalence of about 0.28%-0.42% in China. It is characterized by persistent synovial inflammation, joint swelling and pain, morning stiffness, and progressive joint destruction, often leading to permanent joint deformities and func

The diagnosis of a chronic disease is often viewed as a major life crisis event, presenting patients with multiple cha

Psychological vulnerability refers to an individual’s tendency to produce negative psychological responses when facing stressful events, manifested as emotional regulation difficulties, cognitive biases, and insufficient coping strategies. Common manifestations of psychological vulnerability in RA patients include depression, anxiety, catastrophizing thinking, and hopelessness. Research indicates that the incidence of depressive symptoms in RA patients is 1.5-2 times that of the general population, with approximately 30%-40% of patients experiencing clinically significant depressive symptoms and 15%-30% exhibiting clear anxiety symptoms. These negative psychological responses not only reduce patients' quality of life but may also exacerbate disease activity through neuro-endocrine-immune pathways, forming a vicious cycle[9-13]. Psychological resilience, as a key component of adaptation ability, is operationally defined in the RA context as the capacity to maintain or rapidly recover adaptive psychological functioning despite disease-related stre

Disease adaptation ability refers to patients’ ability to adjust cognition, emotions, and behaviors to cope with disease-related challenges, manifested as disease acceptance, self-efficacy, adoption of positive coping strategies, and recon

Psychological vulnerability and disease adaptation ability are not static characteristics but display dynamic changes throughout the disease course. Particularly as RA is a fluctuating disease, with symptom severity and functional limita

Past research has mostly adopted cross-sectional designs, providing only snapshots of psychological states at specific time points, making it difficult to reveal the developmental trajectory of psychological adaptation. In recent years, with the application of longitudinal research designs and multi-level analysis methods, scholars have begun to focus on the dynamic change patterns of psychological vulnerability and adaptation ability. For example, a 5-year tracking study found that RA patients’ psychological states exhibit three typical trajectories: Consistently good (45%), fluctuating im

Psychological vulnerability and disease adaptation ability are influenced by multiple factors, including individual, disease, social environment, and treatment factors. Regarding individual factors, gender differences are notable, with female patients at higher risk for depression than males; age is also an important variable, with younger patients facing more role conflicts, while elderly patients face dual challenges of functional loss and reduced social support; among personality traits, neuroticism is associated with higher psychological vulnerability, while optimism and resilience promote positive adaptation. Among disease factors, pain intensity has been confirmed as one of the strongest predictors of psychological vulnerability, with Sturgeon and Zautra’s research indicating that persistent pain increases psychological vulnerability by depleting cognitive resources and reinforcing threat cognition; disease activity fluctuations and functional decline typically trigger adjustments in adaptation strategies. Among social environmental factors, supportive family environments and good doctor-patient relationships have protective effects in alleviating psychological vulnerability and promoting adaptation. Regarding treatment factors, new treatments such as biologics not only improve disease activity but also indirectly improve psychological state by reducing inflammatory factors; while treatment side effects and economic burden may increase psychological vulnerability[24-27].

With the promotion of precision medicine concepts, psychological interventions for RA patients increasingly emphasize individualization and stage-specificity. Previous research indicates that patients at different stages face different psychological challenges: Initially focusing on coping with disease uncertainty and treatment decisions; during treatment adjustment periods, managing side effects and expectations; and during long-term adaptation periods, focusing on establishing new normalcy and preventing fear of recurrence. This requires psychological interventions to be adjusted according to patients’ stage and specific needs. Currently, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), acceptance and commitment therapy, mindfulness-based stress reduction, and peer support groups have all shown positive effects, particularly in alleviating depression and anxiety symptoms, enhancing self-efficacy, and improving quality of life[28-31].

Despite significant progress in existing research, several key issues remain to be resolved: (1) Lack of multidimensional assessment systems integrating biomarkers, making it difficult to comprehensively reveal the biopsychosocial mechanisms of psychological vulnerability and disease adaptation; (2) Lack of in-depth research on psychological characteristics of RA patients in the Chinese cultural context; (3) Most research focuses on symptom relief as the primary endpoint, with insufficient attention to outcomes valued by patients such as quality of life and functional recovery; and (4) Intervention research often focuses on specific stages, lacking continuous support strategies throughout the entire disease course[32-35].

In summary, research on psychological vulnerability and disease adaptation ability in RA patients has important theoretical and practical significance. In-depth understanding of their dynamic change patterns and influencing factors helps develop precise, stage-specific psychological intervention strategies to improve patients’ overall health status. This review aims to summarize research progress in this field, providing references for future research and clinical practice[36-38].

Meta-analyses show that the incidence of depressive symptoms in RA patients is 30%-40%, significantly higher than in the general population (10%-15%); anxiety symptom incidence is 15%-30%, catastrophizing thinking incidence is 25%-35%, and hopelessness occurrence rate is approximately 22%[39-41]. Demographic characteristic analysis indicates that female patients have 1.8 times the risk of psychological vulnerability compared to males, and patients aged < 45 years have higher psychological vulnerability risk than elderly patients (relative risk ratio 1.42), possibly related to the multiple role pressures faced by younger patients, including career and parenting. Clinical correlation studies show that psychological vulnerability is moderately positively correlated with disease activity and strongly negatively correlated with quality of life[42,43]. Throughout the disease course, psychological vulnerability indicators reach their first peak 3-6 months after diagnosis [Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) average score increases by 5.2 points], followed by partial improvement when disease control is good. Multicenter longitudinal studies indicate that among patients without psychological intervention, approximately 25% remain in a state of high psychological vulnerability long-term, accompanied by higher treatment resistance rates (increased by 38%) and functional disability risk (hazard ratio = 1.76). Compared with other chronic diseases (such as diabetes, systemic lupus erythematosus)[44,45], psychological vulnerability in RA patients lasts longer, extended by an average of 6.4 months, suggesting the existence of disease-specific mechanisms[46].

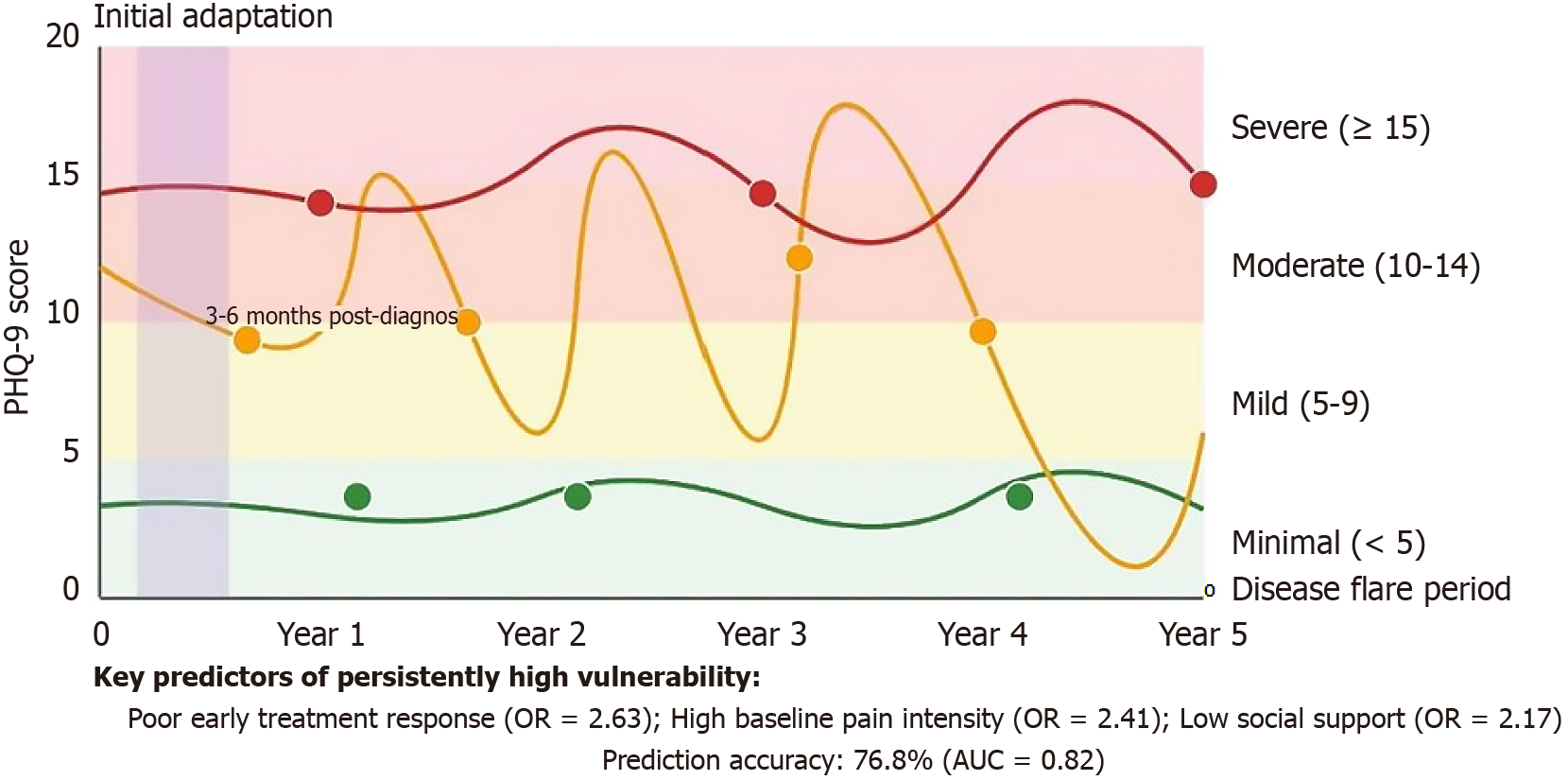

Based on latent class growth analysis from a 5-year tracking study (n = 328), RA patients’ psychological vulnerability exhibits three typical trajectories: Persistently low vulnerability (45%, PHQ-9 average score < 5 points), fluctuating improvement (30%, initial PHQ-9 average score 12.4 points, fluctuation range 4.6-14.2 points), and persistently high vulnerability (25%, PHQ-9 average score > 12 points)[47,48]. Time series analysis shows that psychological vulnerability significantly increases during disease activity periods [Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) anxiety score increases by an average of 4.6 points], decreases during remission periods (decreases by an average of 2.8 points), but even during long-term remission does not completely return to baseline levels (residual score averages 1.8 points higher), indicating a cumulative effect of psychological damage (accumulated effect index = 0.37)[49-51]. The first 3-6 months after initial diagnosis (initial adaptation period) and disease exacerbation periods are high-incidence periods for psychological vulnerability, with the former correlated with disease uncertainty and treatment decision pressure, while the latter is closely related to fear of functional loss and decreased sense of control. Multivariate prediction models show that poor early treatment response, high baseline pain intensity, and low social support are the three main factors predicting persistently high vulnerability trajectories, with an accuracy of 76.8%. This dynamic change pattern has important guiding significance for clinical intervention timing and individualized strategy selection[52-56].

Evidence-based protocols for psychological support adjustment during RA flares include: (1) Rapid psychological assessment using modified HADS with flare-specific items (Flare Psychological Impact Scale) administered within 48 hours of flare onset; (2) Intensified intervention schedules increasing CBT sessions from monthly to weekly during high-activity periods [Disease Activity Score in 28 Joints (DAS28) > 5.1], with emergency psychological consultations available within 24 hours; and (3) Flare-specific mindfulness techniques including acute pain acceptance protocols and anxiety regulation breathing exercises adapted for joint stiffness limitations. Based on reviewed studies showing 4.6-point increases in anxiety scores during flares, intervention thresholds are established at HADS anxiety scores ≥ 12 or PHQ-9 scores ≥ 10 during active disease periods, triggering immediate psychological support activation.

A 3-year longitudinal study (n = 246) using mixed research methods reveals that RA patients’ disease adaptation presents four distinct stages: Initial shock period (0-3 months), characterized by denial (average Childhood Obesity Perceived Exertion Scale-D subscale score 11.4) and strong emotional responses (HADS anxiety average score 10.2); exploration adjustment period (3-12 months), when patients begin actively seeking information (information seeking behavior increases by 68%) and coping strategies (Childhood Obesity Perceived Exertion Scale positive coping subscale increases by an average of 4.3 points); stable reconstruction period (1-2 years), forming relatively stable disease management patterns, with significantly improved self-efficacy (Rheumatoid Arthritis Self-efficacy scale increases by an average of 7.8 points); long-term integration period (> 2 years), integrating disease experience into life, reaching highest acceptance (acceptance scale average score increases by 59%), while sense of life meaning recovers (Purpose in Life Test scores recover to near pre-diagnosis levels, reaching 95.4%)[57,58]. Inflammatory mediator studies demonstrate that circulating pro-inflammatory cytokine levels are significantly positively correlated with depressive symptoms, particularly interleukin (IL)-6, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and IL-1β. These pro-inflammatory factors constitute an “inflammation-neurotransmitter dysregulation” pathway by affecting serotonin metabolism, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression, and glutamatergic system function. Meanwhile, there exists a critical triangular relationship between vagus nerve function, inflammatory biomarkers, and psychological adaptation capacity. Patients with reduced heart rate variability (HRV) exhibit significantly elevated inflammatory levels and markedly diminished disease acceptance. These findings reveal the crucial role of “neural-immune-psychological” network dysfunction in disease adaptation processes, providing a new theoretical foundation for comprehensive treatment of RA patients (Figure 1).

Multicenter studies (n = 412) using multivariate analysis show significant differences in how various individual characteristics affect psychological vulnerability and adaptation ability. Among demographic characteristics, higher education level (≥ university) is significantly associated with lower psychological vulnerability, with this protective effect most significant in the early disease stages; age has a U-shaped relationship with adaptation patterns, with middle-aged patients (35-55 years) having the highest risk of adaptation difficulties, possibly related to multiple role pressures[59,60]. Personality trait analysis finds that optimistic personality is a strong predictor of good adaptation ability, resilience increases disease acceptance; while neurotic personality is highly positively correlated with psychological vulnerability (r = 0.62), increasing catastrophizing thinking (odds ratio = 2.34). Regarding cognitive assessment, patients with high disease threat perception have 2.4 times increased risk of depression, while control perception is an independent predictor of good adaptation. Path analysis finds that stigma and self-efficacy are key mediating variables, jointly explaining 38.5% of individual differences, with self-efficacy having the greatest impact on treatment adherence (indirect effect coefficient 0.42)[61,62]. Cross-cultural comparative studies indicate that for Chinese patients with collectivist cultural backgrounds, the ability to maintain social roles has a greater impact on psychological health (β difference 0.17), while sense of personal achievement has more significant influence in Western samples, suggesting the moderating effect of cultural background in individual factor mechanisms. Prospective studies further confirm that early assessment of individual factors has a 76.3% predictive accuracy for psychological health status 3 years later, providing a theoretical basis for early intervention[63,64].

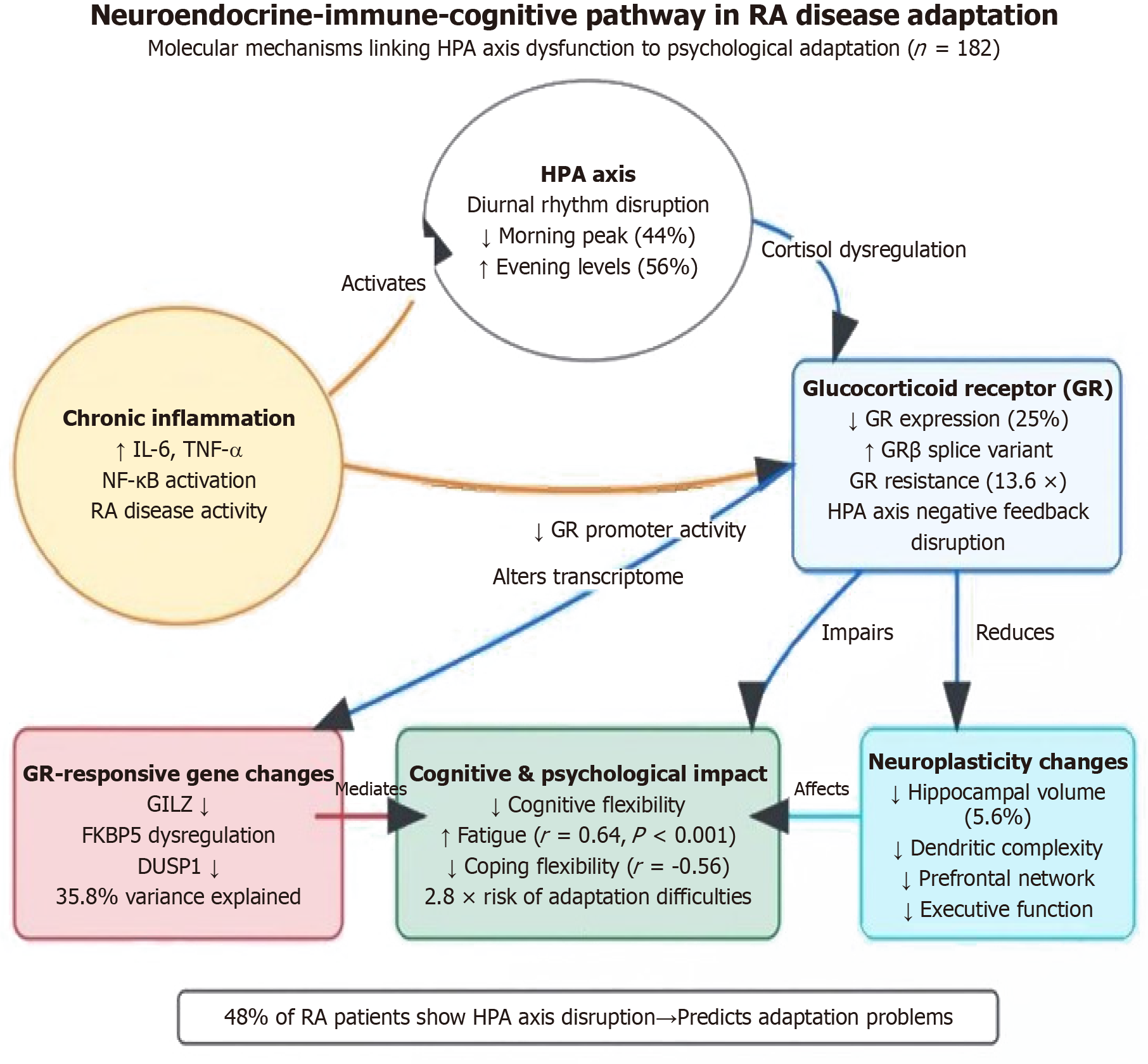

Large prospective studies (n = 182) reveal significant hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis dysfunction in RA patients, with approximately 48% of patients showing cortisol diurnal rhythm disruption (morning peak decreased by 44%, evening levels increased by 56%). This endocrine dysregulation strongly negatively correlates with coping flexibility (r = -0.56) and independently predicts a 2.8-fold increased risk of disease adaptation difficulties six months later [95% confidence interval (CI): 1.9-4.2][65,66]. Molecular mechanism studies elucidate an “inflammation-HPA axis-cognition” pathway: Chronic inflammation (especially IL-6, TNF-α) activates nuclear factor κB signaling pathways, downregulates glucocorticoid receptor (GR) gene promoter activity, and promotes GRβ splice variant production, leading to GR ex

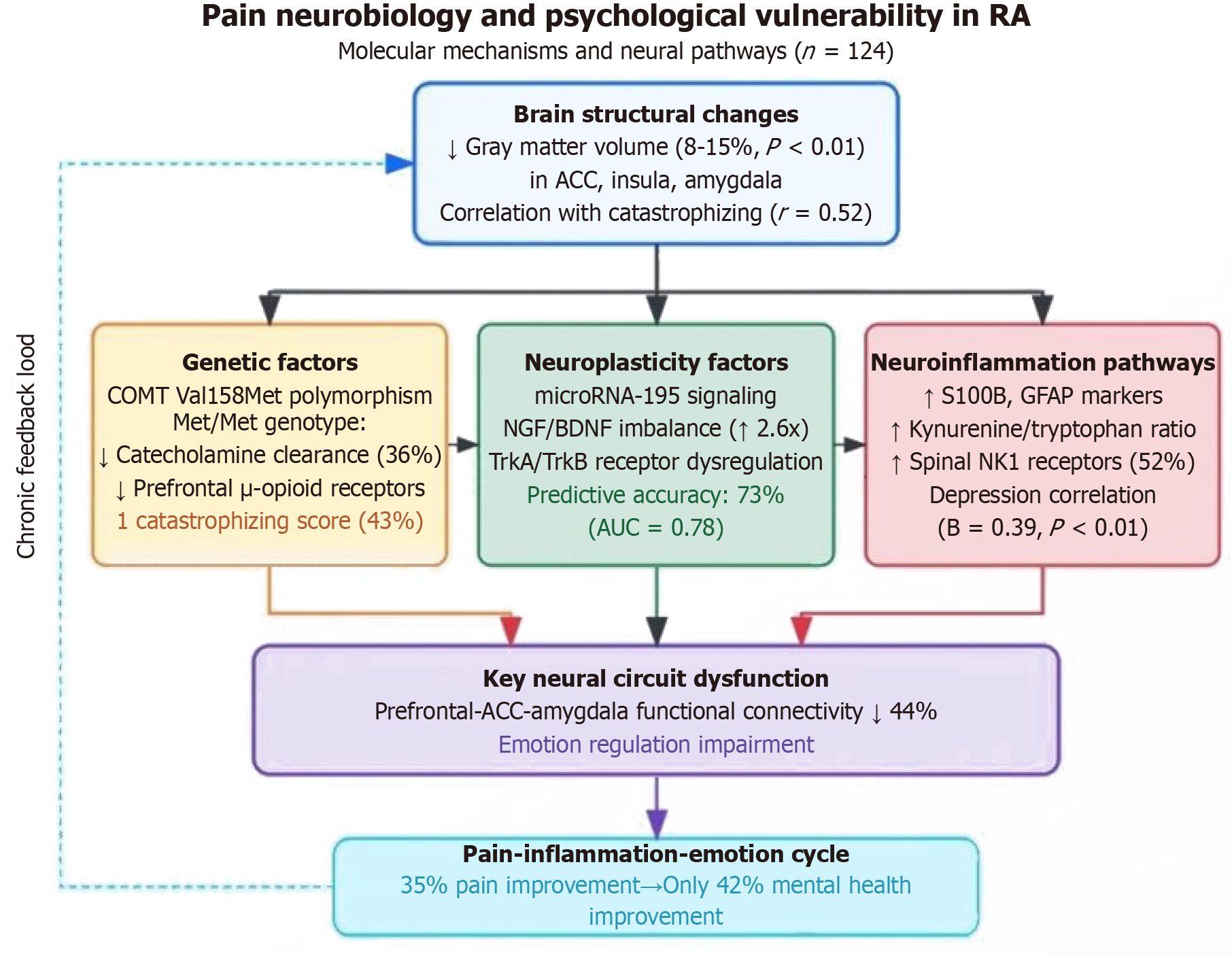

Large integrated neuroimaging studies (n = 124) reveal that key nodes in RA patients’ pain processing networks (anterior cingulate cortex, insula, amygdala) show significantly reduced gray matter volume (8%-15%), with these structural changes strongly positively correlated with pain catastrophizing thinking (r = 0.52)[71,72]. Molecular genetic analysis identifies COMT Val158Met gene polymorphism as a key susceptibility factor, with Met/Met genotype patients having 36% decreased catecholamine clearance rates, leading to prefrontal μ-opioid receptor downregulation, enhanced pain signals, and 43% higher catastrophizing scores[73,74]. Neural plasticity molecular studies find that persistent chronic pain disrupts neurotrophin balance by activating microRNA-195 signaling pathways, manifested as abnormally elevated nerve growth factor/BDNF ratios (2.6-fold) and imbalanced tropomyosin receptor kinase A/tropomyosin receptor kinase B receptor expression ratios, with these molecular features predicting psychological vulnerability with 73% accuracy (area under the curve = 0.78)[75,76]. Connectomic and metabolomic integrated analyses further reveal three key pathways: First, reduced functional connectivity strength (44%) between the prefrontal cortex-anterior cingulate cortex-amygdala associated with emotional regulation disorders; second, spinal neurokinin-1 receptor overexpression (increased by 52%) mediating central sensitization; and third, elevated neuroinflammation indicators (S100B, glial fibrillary acidic protein, kynurenine/tryptophan ratio) independently correlated with depressive symptoms[77]. These findings construct a closed-loop “pain-inflammation-emotion” model, explaining why 85% improvement in pain intensity translates to only 42% improvement in psychological health (Figure 3), providing a molecular basis for coordinated treatment of pain and psychological interventions[78,79].

Multicenter studies (n = 246) find that circulating pro-inflammatory cytokine levels in RA patients are significantly positively correlated with depressive symptoms, with IL-6 (r = 0.48), TNF-α (r = 0.42), and IL-1β (r = 0.37) showing the strongest correlations. Longitudinal studies confirm that for each standard deviation increase in serum IL-6 levels, PHQ-9 depression scores increase by an average of 2.6 points (95%CI: 1.8-3.4)[80,81]. Functional magnetic resonance imaging studies show that RA patients with high inflammatory burden exhibit weakened functional connectivity between the prefrontal cortex and amygdala (reduced by 32%), significantly correlated with decreased emotional regulation capacity. Molecular pathway analysis indicates that these pro-inflammatory factors exert their effects by influencing serotonin metabolism (reducing 5-hydroxytryptamine bioavailability by 28%), BDNF expression (downregulated by 42%), and glutamatergic system function, constituting an “inflammation-neurotransmitter dysregulation" pathway[82,83].

Groundbreaking bidirectional communication studies (n = 136) between peripheral blood and central nervous systems in RA patients reveal a critical triangular relationship between vagus nerve function (measured by HRV), inflammatory biomarkers, and psychological adaptation capacity. Patients with reduced HRV (root mean square of successive differences < 20 millisecond) demonstrate significantly elevated IL-6 and C-reactive protein levels (averaging 28% higher) alongside markedly diminished disease acceptance and positive coping strategies (differences reaching 40%). Molecular marker analysis of neuroimmune regulation pathways identifies downregulated α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor expression as independently associated with chronic fatigue and psychological adaptation difficulties, establishing a direct molecular link between neural cholinergic signaling and psychological outcomes[84,85]. Comprehensive metabolic-inflammatory network analysis further confirms that imbalanced ω-3/ω-6 polyunsaturated fatty acid ratios (reduced by 56%) modulate neuroimmune interactions and emotional responses through altered resolvin and prostaglandin production equilibrium. These findings collectively demonstrate the crucial role of integrated “neural-immune-psychological” network dysfunction in disease adaptation processes, suggesting new therapeutic targets at the interface of neurological, immunological, and psychological systems for improving adaptation outcomes in RA patients[86,87].

Mechanistic research reveals that biologics improve psychological symptoms through multiple pathways: TNF-α in

Systematic randomized controlled trials (n = 864) comprehensively evaluated four major psychological intervention methods, with results indicating that different methods have differentiated advantages[88,89]. CBT showed the most significant improvement effect on depressive symptoms (Cohen’s d = 0.68, 95%CI: 0.52-0.84), with patients’ PHQ-9 scores decreasing by an average of 5.2 points after 12 weeks of intervention, achieving a remission rate of 62.8%; while mindfulness-based stress reduction therapy, although slightly less effective than CBT for depression improvement (Cohen’s d = 0.53), was significantly superior to CBT in reducing catastrophizing thinking (Pain Catastrophizing Scale scores decreased by 44% vs 27%) and increasing pain acceptance (Cognitive and Physical Activity Questionnaire scores increased by 38% vs 21%) , particularly suitable for patients with high pain comorbidity[90-94]. Peer support groups, although showing moderate effects in symptom improvement (Cohen’s d = 0.42, 95%CI: 0.28-0.56), demonstrated clear advantages in promoting disease meaning reconstruction (meaning scale increased by 25.6%) and social function recovery (social participation increased by 47%), with the highest cost-effectiveness ratio (incremental cost-effectiveness ratio = 2640 yuan/quality-adjusted life year)[95-98]. Dose-response analysis shows that CBT and mindfulness-based stress reduction require at least 8 sessions to achieve clinically significant effects, while peer support group effectiveness linearly correlates with participation frequency. Long-term follow-up (6-36 months) data indicate that comprehensive disease management programs (integrating drug therapy, psychological intervention, and self-management) have the most lasting effects on quality of life improvement, with the most pronounced advantage at 12 months (between-group effect size reaching 0.76) and the lowest recurrence rate (18% vs 27%-41%), related to its synergistic effect on multidimensional health factors[99-102]. Notably, recently developed online intervention platforms not only have high accessibility (increasing coverage of rural patients by 84%) but also superior adherence compared to traditional face-to-face methods (completion rate 68% vs 54%), particularly suitable for resource-limited areas, providing new approaches for popularizing psychological interventions. Multivariate analysis suggests that personalized intervention matching (based on patients’ depression subtypes, coping styles, and preferences) can further improve treatment effectiveness (average gain effect reaching 26%), representing future research directions[103-105].

Large prospective cohort studies (n = 346) confirmed through 3-year strict follow-up that psychological interventions initiated within 3 months after diagnosis have significant protective effects on long-term psychological health in RA patients[106,107]. Compared with routine care groups, early intervention groups showed 42% lower depression incidence (18.4% vs 31.7%), 56% reduced risk of depression recurrence (hazard ratio = 0.44, 95%CI: 0.31-0.62), 31% higher good disease adaptation rates (65.2% vs 49.8%), and 28% higher work capacity retention rates (83.6% vs 65.3%), with these protective effects persisting for 24-36 months after intervention completion. Dose-response analysis found that at least 6 psychological intervention sessions are needed to produce lasting effects, and intervention content needs to integrate disease education, stress management, and adaptation skills training. Subgroup analysis showed that early screening and intervention targeting high-risk populations (female, age < 45 years, baseline DAS28 > 5.1) is particularly effective (number needed to treat = 4.3 vs 8.6), with the highest cost-effectiveness ratio (incremental cost-effectiveness ratio = 4580 yuan/quality-adjusted life year), saving direct medical costs and indirect social costs totaling 12460 yuan/patient/year compared to delayed intervention[108,109]. Implementation pathway analysis found that integrating psychological screening and risk assessment into standard RA treatment processes can significantly increase intervention coverage (from 18.4% to 76.3%), while training rheumatology nurses to provide primary psychological support can effectively address professional staffing shortages. Long-term follow-up data further confirmed that early psychological intervention not only improves psychological health but also indirectly improves disease activity (average DAS28 decreased by 0.6 points, P < 0.05) by increasing treatment adherence, demonstrating the synergistic effect of bio-psycho-social integrated interventions[110-114].

A comprehensive biologic therapy cohort study (n = 216) demonstrates that beyond reducing disease activity, TNF-α inhibitors significantly improve depression symptoms after 6 months of treatment (PHQ-9 scores decreased by 4.2 points), with this improvement partially independent of disease activity changes (partial correlation r = 0.36 after controlling for DAS28)[115,116]. Mechanistic investigations reveal that TNF-α inhibitors directly enhance neuronal plasticity and synaptic function by reducing blood-brain barrier permeability (decreased by 32%) and attenuating central nervous system inflammation. Similarly, Janus kinase inhibitors (such as tofacitinib) significantly reduce serum indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activity (decreased by 46%) and lower kynurenine/tryptophan ratios, strongly correlating with depression symptom improvement (r = 0.59, P < 0.001). Pharmacogenomic studies further identify that FKBP5 and solute carrier family 6 member 4 gene polymorphisms substantially influence psychological outcomes of anti-rheumatic medications, with FKBP5 risk allele carriers showing 36% less improvement in depressive symptoms (P < 0.01), establishing a molecular foundation for personalized treatment approaches that simultaneously target both inflammatory disease activity and psychological vulnerability in RA patients[117-119].

An innovative integrative research study (n = 158) employing multi-omics approaches has identified three distinct molecular response patterns to stress in RA patients, each with profound implications for psychological adaptation[120-122]. The most common “adaptive pattern” (52% of patients) exhibits balanced cortisol response curves, moderate pro-inflammatory marker elevations, and rapid recovery phases, while “high-response” (28%) and “low-response” (20%) patterns demonstrate either excessive sympathetic activation with persistent inflammation or blunted stress responses with chronic low-grade inflammation, respectively[123,124]. These molecular phenotypes demonstrate remarkable concordance with psychological adaptation trajectories (78.4% consistency rate), with adaptive-pattern patients showing significantly enhanced psychological resilience (Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale scores averaging 12 points higher)[125-127]. Epigenetic transcriptomic analysis further reveals that adaptive-pattern patients exhibit dynamic post-stress gene expression changes across 155 genes involved in stress regulation, neuroplasticity, and immune homeostasis, with nuclear receptor subfamily 3 group C member 1 (GR), FKBP5 (stress hormone regulator), and IL10 (anti-inflammatory cytokine) showing the most significant expression pattern alterations[128-131]. These findings substantiate a “molecular coping phenotype-psychological adaptation” connection model, providing critical insights into the biological under

A sophisticated metabolomics investigation (n = 142) has successfully identified 14 small-molecule metabolites strongly associated with psychological resilience in RA patients encompassing four critical biochemical domains: Tryptophan metabolism pathway components (5-hydroxytryptamine, kynurenine), one-carbon metabolism markers (S-adenosylmethionine/S-adenosylhomocysteine ratio), lipid metabolism products (omega-3 derivatives), and gut microbiome-derived metabolites (short-chain fatty acids)[137-141]. These findings enabled researchers to develop a “psychological resilience molecular fingerprint” model with remarkable predictive capacity for long-term psychological outcomes, accurately forecasting patients’ adaptation status two years post-assessment with 81.6% precision (area under the curve = 0.83). Longitudinal analyses further validated these associations, demonstrating that serum concentrations of sodium butyrate, neuroprotective N-acetamide compounds, and specific dietary polyphenol metabolites exhibit robust positive correlations with adaptive psychological parameters including positive coping strategies and self-efficacy[142-146]. This groundbreaking research establishes a comprehensive molecular foundation for developing novel intervention app

The findings emphasize integrating routine psychological assessment into standard RA care through evidence based protocols, developing personalized bio-psycho-social intervention strategies tailored to disease stages and individual needs, and implementing dynamic adjustment mechanisms during disease flares to optimize psychological outcomes throughout the disease course.

| 1. | La R, Yin Y, Xu B, Huang J, Zhou L, Xu W, Jiang D, Huang L, Wu Q. Mediating role of depression in linking rheumatoid arthritis to all-cause and cardiovascular-related mortality: A prospective cohort study. J Affect Disord. 2024;362:86-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Adas M, Dey M, Norton S, Lempp H, Buch MH, Cope A, Galloway J, Nikiphorou E. What role do socioeconomic and clinical factors play in disease activity states in rheumatoid arthritis? Data from a large UK early inflammatory arthritis audit. RMD Open. 2024;10:e004180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Al-Ewaidat OA, Naffaa MM. Stroke risk in rheumatoid arthritis patients: exploring connections and implications for patient care. Clin Exp Med. 2024;24:30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Baerwald C, Stemmler E, Gnüchtel S, Jeromin K, Fritz B, Bernateck M, Adolf D, Taylor PC, Baron R. Predictors for severe persisting pain in rheumatoid arthritis are associated with pain origin and appraisal of pain. Ann Rheum Dis. 2024;83:1381-1388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Balsa A, García de Yébenes MJ, Carmona L; ADHIERA Study Group. Multilevel factors predict medication adherence in rheumatoid arthritis: a 6-month cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81:327-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bechman K, Yates M, Norton S, Cope AP, Galloway JB. Placebo Response in Rheumatoid Arthritis Clinical Trials. J Rheumatol. 2020;47:28-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ionescu CE, Popescu CC, Agache M, Dinache G, Codreanu C. Depression in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Narrative Review-Diagnostic Challenges, Pathogenic Mechanisms and Effects. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022;58:1637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Boussaid S, Jeriri S, Rekik S, Hannech E, Jammali S, Cheour E, Sahli H, Elleuch M. Influencing Factors in Tunisian Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients' Quality of Life: Burden and Solutions. Curr Rheumatol Rev. 2023;19:314-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bucourt E, Martaillé V, Goupille P, Joncker-Vannier I, Huttenberger B, Réveillère C, Mulleman D, Courtois AR. A Comparative Study of Fibromyalgia, Rheumatoid Arthritis, Spondyloarthritis, and Sjögren's Syndrome; Impact of the Disease on Quality of Life, Psychological Adjustment, and Use of Coping Strategies. Pain Med. 2021;22:372-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bulut N, Tezcan ME. Emotional eating is more frequent in obese rheumatoid arthritis patients. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2020;35:81-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bunnewell S, Wells I, Zemedikun D, Simons G, Mallen CD, Raza K, Falahee M. Predictors of perceived risk in first-degree relatives of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. RMD Open. 2022;8:e002606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Calderón Espinoza I, Chavarria-Avila E, Pizano-Martinez O, Martínez-García EA, Armendariz-Borunda J, Marquez-Aguirre AL, Llamas-García A, Corona-Sánchez EG, Toriz González G, Vazquez-Del Mercado M. Suicide Risk in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients is Associated With Suboptimal Vitamin D Levels. J Clin Rheumatol. 2022;28:137-142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Carpenter L, Barnett R, Mahendran P, Nikiphorou E, Gwinnutt J, Verstappen S, Scott DL, Norton S. Secular changes in functional disability, pain, fatigue and mental well-being in early rheumatoid arthritis. A longitudinal meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2020;50:209-219. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Chan SJ, Stamp LK, Liebergreen N, Ndukwe H, Marra C, Treharne GJ. Tapering Biologic Therapy for Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Qualitative Study of Patient Perspectives. Patient. 2020;13:225-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chan SJ, Yeo HY, Stamp LK, Treharne GJ, Marra CA. What Are the Preferences of Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis for Treatment Modification? A Scoping Review. Patient. 2021;14:505-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chaplin H, Carpenter L, Raz A, Nikiphorou E, Lempp H, Norton S. Summarizing current refractory disease definitions in rheumatoid arthritis and polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis: systematic review. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60:3540-3552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Chaurasia N, Singh A, Singh IL, Singh T, Tiwari T. Cognitive dysfunction in patients of rheumatoid arthritis. J Family Med Prim Care. 2020;9:2219-2225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Conran C, Kolfenbach J, Kuhn K, Striebich C, Moreland L. A Review of Difficult-to-Treat Rheumatoid Arthritis: Definition, Clinical Presentation, and Management. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2023;25:285-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | De Cock D, Doumen M, Vervloesem C, Van Breda A, Bertrand D, Pazmino S, Westhovens R, Verschueren P. Psychological stress in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic scoping review. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2022;55:152014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Doumen M, Diricks L, Hermans J, Bertrand D, De Meyst E, Westhovens R, Verschueren P. Definitions of rheumatoid arthritis flare and how they relate to patients' perspectives: A scoping review of qualitative and quantitative evidence. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2024;67:152481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Doumen M, Pazmino S, Verschueren P, Westhovens R. Viewpoint: Supporting mental health in the current management of rheumatoid arthritis: time to act! Rheumatology (Oxford). 2023;62:SI274-SI281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Drakes DH, Fawcett EJ, Yick JJJ, Coles ARL, Seim RB, Miller K, LaSaga MS, Fawcett JM. Beyond rheumatoid arthritis: A meta-analysis of the prevalence of anxiety and depressive disorders in rheumatoid arthritis. J Psychiatr Res. 2025;184:424-438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Dubois-Mendes SM, Sá KN, Meneses FM, De Andrade DC, Baptista AF. Neuropathic pain in rheumatoid arthritis and its association with Afro-descendant ethnicity: a hierarchical analysis. Psychol Health Med. 2021;26:278-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Morf H, da Rocha Castelar-Pinheiro G, Vargas-Santos AB, Baerwald C, Seifert O. Impact of clinical and psychological factors associated with depression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: comparative study between Germany and Brazil. Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40:1779-1787. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Dunne PJ, Schubert C. Editorial: New Mind-Body Interventions That Balance Human Psychoneuroimmunology. Front Psychol. 2021;12:706584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Farhat H, Irfan H, Muthiah K, Pallipamu N, Taheri S, Thiagaraj SS, Shukla TS, Gutlapalli SD, Giva S, Penumetcha SS. Increased Risk of Cardiovascular Diseases in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2022;14:e32308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Fayet F, Pereira B, Fan A, Rodere M, Savel C, Berland P, Soubrier M, Tournadre A, Dubost JJ. Therapeutic education improves rheumatoid arthritis patients' knowledge about methotrexate: a single center retrospective study. Rheumatol Int. 2021;41:2025-2030. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Feng J, Yu L, Fang Y, Zhang X, Li S, Dou L. Correlation between disease activity and patient-reported health-related quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2024;14:e082020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Fenton SAM, Ntoumanis N, Duda JL, Metsios GS, Rouse PC, Yu CA, Kitas GD, Veldhuijzen van Zanten JJCS. Diurnal patterns of sedentary time in rheumatoid arthritis: associations with cardiovascular disease risk. RMD Open. 2020;6:e001216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Galvez-Sánchez CM, de la Coba P, Colmenero JM, Reyes Del Paso GA, Duschek S. Attentional function in fibromyalgia and rheumatoid arthritis. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0246128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Geng Y, Gao T, Zhang X, Wang Y, Zhang Z. The association between disease duration and mood disorders in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Clin Rheumatol. 2022;41:661-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Germain V, Scherlinger M, Barnetche T, Pichon C, Balageas A, Lequen L, Shipley E, Foret J, Dublanc S, Capuron L, Schaeverbeke T; Fédération Hospitalo-Universitaire ACRONIM. Role of stress in the development of rheumatoid arthritis: a case-control study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60:629-637. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Grekhov RA, Suleimanova GP, Trofimenko AS, Shilova LN. Psychosomatic Features, Compliance and Complementary Therapies in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rev. 2020;16:215-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Gwinnutt JM, Toyoda T, Jeffs S, Flanagan E, Chipping JR, Dainty JR, Mioshi E, Hornberger M, MacGregor A. Reduced cognitive ability in people with rheumatoid arthritis compared with age-matched healthy controls. Rheumatol Adv Pract. 2021;5:rkab044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Habers GEA, van der Helm-van Mil AHM, Veldhuijzen DS, Allaart CF, Vreugdenhil E, Starreveld DEJ, Huizinga TWJ, Evers AWM. Earlier chronotype in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2021;40:2185-2192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Hammad M, Eissa M, Dawa GA. Factors contributing to disability in rheumatoid arthritis patients: An Egyptian multicenter study. Reumatol Clin (Engl Ed). 2020;16:103-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Hammam N, Gamal RM, Rashed AM, Elfetoh NA, Mosad E, Khedr EM. Fatigue in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients: Association With Sleep Quality, Mood Status, and Disease Activity. Reumatol Clin (Engl Ed). 2020;16:339-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Hammond A, Tennant A, Brown T, Prior Y, Ching A, Parker J. Psychometric testing of the Rheumatoid Arthritis Work Instability Scale in employed people with fibromyalgia. Musculoskeletal Care. 2023;21:1434-1446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Haridoss M, Bagepally BS, Natarajan M. Health-related quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis: Systematic review and meta-analysis of EuroQoL (EQ-5D) utility scores from Asia. Int J Rheum Dis. 2021;24:314-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Haroon M, Szentpetery A, Ashraf M, Gallagher P, FitzGerald O. Bristol rheumatoid arthritis fatigue scale is valid in patients with psoriatic arthritis and is associated with overall severe disease and higher comorbidities. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39:1851-1858. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Hegarty RSM, Conner TS, Stebbings S, Fletcher BD, Harrison A, Treharne GJ. Understanding Fatigue-Related Disability in Rheumatoid Arthritis and Ankylosing Spondylitis: The Importance of Daily Correlates. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2021;73:1282-1289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Hu H, Xu A, Wang Z, Gao C, Wu X. Self-Management Behaviours in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients: What Role Do Health Beliefs Play? Int J Nurs Pract. 2025;31:e13320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Zhao H, Dong Q, Hua H, Wu H, Ao L. Contemporary insights and prospects on ferroptosis in rheumatoid arthritis management. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1455607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Ifesemen OS, McWilliams DF, Ferguson E, Wakefield R, Akin-Akinyosoye K, Wilson D, Platts D, Ledbury S, Walsh DA. Central Aspects of Pain in Rheumatoid Arthritis (CAP-RA): protocol for a prospective observational study. BMC Rheumatol. 2021;5:23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Ifesemen OS, McWilliams DF, Norton S, Kiely PDW, Young A, Walsh DA. Fatigue in early rheumatoid arthritis: data from the Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Network. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2022;61:3737-3745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Han ZY, Chen Y, Chen YD, Sun GM, Dai XY, Yin YQ, Geng YQ. Latent characteristics and influencing factors of stigma in rheumatoid arthritis: A latent class analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102:e34006. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Ingram T, Sengupta R, Standage M, Barnett R, Rouse P. Correlates of physical activity in adults with spondyloarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review. Rheumatol Int. 2022;42:1693-1713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Itaya T, Torii M, Hashimoto M, Tanigawa K, Urai Y, Kinoshita A, Nin K, Jindai K, Watanabe R, Murata K, Murakami K, Tanaka M, Ito H, Matsuda S, Morinobu A. Prevalence of anxiety and depression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60:2023-2024. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Jackson T, Xu T, Jia X. Arthritis self-efficacy beliefs and functioning among osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis patients: a meta-analytic review. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020;59:948-958. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Janiszewska M, Barańska A, Kanecki K, Karpińska A, Firlej E, Bogdan M. Coping strategies observed in women with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2020;27:401-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Karaca NB, Arin-Bal G, Sezer S, Kelesoglu Dincer AB, Kinikli G, Boström C, Kinikli GI. Physical Activity, Kinesiophobia, Pain Catastrophizing, Body Awareness, Depression and Disease Activity in Patients With Ankylosing Spondylitis and Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Cross-Sectional Explorative Study. Musculoskeletal Care. 2024;22:e1953. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Khidir SJH, de Jong PHP, Willemze A, van der Helm-van Mil AHM, van Mulligen E. Clinically suspect arthralgia and rheumatoid arthritis: patients' perceptions of illness. Joint Bone Spine. 2024;91:105751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Larkin L, McKenna S, Pyne T, Comerford P, Moses A, Folan A, Gallagher S, Glynn L, Fraser A, Esbensen BA, Kennedy N. Promoting physical activity in rheumatoid arthritis through a physiotherapist led behaviour change-based intervention (PIPPRA): a feasibility randomised trial. Rheumatol Int. 2024;44:779-793. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Leese J, Backman CL, Ma JK, Koehn C, Hoens AM, English K, Davidson E, McQuitty S, Gavin J, Adams J, Therrien S, Li LC. Experiences of self-care during the COVID-19 pandemic among individuals with rheumatoid arthritis: A qualitative study. Health Expect. 2022;25:482-498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Looijen AEM, Snoeck Henkemans SVJ, van der Helm-van Mil AHM, Welsing PMJ, Koc GH, Luime JJ, Kok MR, Tchetverikov I, Korswagen LA, Baudoin P, Vis M, de Jong PHP. Combining patient-reported outcome measures to screen for active disease in rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis. RMD Open. 2024;10:e004687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Ma L, Yuan J, Yang X, Yan M, Li Y, Niu M. Association between the adherence to Mediterranean diet and depression in rheumatoid arthritis patients: a cross-sectional study from the NHANES database. J Health Popul Nutr. 2024;43:103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Machin AR, Babatunde O, Haththotuwa R, Scott I, Blagojevic-Bucknall M, Corp N, Chew-Graham CA, Hider SL. The association between anxiety and disease activity and quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39:1471-1482. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Malcangio M. Translational value of preclinical models for rheumatoid arthritis pain. Pain. 2020;161:1399-1400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Martinez-Calderon J PT, MSc, Meeus M PT, PhD, Struyf F PT, PhD, Luque-Suarez A PT, PhD. The role of self-efficacy in pain intensity, function, psychological factors, health behaviors, and quality of life in people with rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review. Physiother Theory Pract. 2020;36:21-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | McBeth J, Dixon WG, Moore SM, Hellman B, James B, Kyle SD, Lunt M, Cordingley L, Yimer BB, Druce KL. Sleep Disturbance and Quality of Life in Rheumatoid Arthritis: Prospective mHealth Study. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24:e32825. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Mednieks J, Naumovs V, Skilters J. Ideational Fluency in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rev. 2021;17:205-212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Mena-Vázquez N, Ortiz-Márquez F, Ramírez-García T, Cabezudo-García P, García-Studer A, Mucientes-Ruiz A, Lisbona-Montañez JM, Borregón-Garrido P, Ruiz-Limón P, Redondo-Rodríguez R, Manrique-Arija S, Cano-García L, Serrano-Castro PJ, Fernández-Nebro A. Impact of inflammation on cognitive function in patients with highly inflammatory rheumatoid arthritis. RMD Open. 2024;10:e004422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Morse JL, Afari N, Norman SB, Guma M, Pietrzak RH. Prevalence, characteristics, and health burden of rheumatoid arthritis in the U.S. veteran population. J Psychiatr Res. 2023;159:224-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Muruganandam A, Migliorini F, Jeyaraman N, Vaishya R, Balaji S, Ramasubramanian S, Maffulli N, Jeyaraman M. Molecular Mimicry Between Gut Microbiome and Rheumatoid Arthritis: Current Concepts. Med Sci (Basel). 2024;12:72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Oh H, Suh CH, Kim JW, Boo S. mHealth-Based Self-Management Program for Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Pilot Randomized Controlled Study. Nurs Health Sci. 2024;26:e13187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Pankowski D, Wytrychiewicz-Pankowska K, Janowski K, Pisula E. Cognitive impairment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Joint Bone Spine. 2022;89:105298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Pankowski D, Wytrychiewicz-Pankowska K, Janowski K, Pisula E. The relationship between primary cognitive appraisals, illness beliefs, and adaptation to rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2023;164:111074. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Pankowski D, Wytrychiewicz-Pankowska K, Pisula E, Fal A, Kisiel B, Kamińska E, Tłustochowicz W. Age, Cognitive Factors, and Acceptance of Living with the Disease in Rheumatoid Arthritis: The Short-Term Perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:3136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Parenti G, Tomaino SCM, Cipolletta S. The experience of living with rheumatoid arthritis: A qualitative metasynthesis. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29:3922-3936. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Park J, Lee M, Lee H, Kim HJ, Kwon R, Yang H, Lee SW, Kim S, Rahmati M, Koyanagi A, Smith L, Kim MS, Jacob L, López Sánchez GF, Elena D, Shin JI, Rhee SY, Yoo MC, Yon DK. National trends in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis prevalence in South Korea, 1998-2021. Sci Rep. 2023;13:19528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Parton C, Ussher JM, Perz J. Mothers' experiences of wellbeing and coping while living with rheumatoid arthritis: a qualitative study. BMC Womens Health. 2022;22:185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Pedard M, Quirié A, Tessier A, Garnier P, Totoson P, Demougeot C, Marie C. A reconciling hypothesis centred on brain-derived neurotrophic factor to explain neuropsychiatric manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60:1608-1619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Perez-Sousa MA, Pedro J, Carrasco-Zahinos R, Raimundo A, Parraca JA, Tomas-Carus P. Effects of Aquatic Exercises for Women with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A 12-Week Intervention in a Quasi-Experimental Study with Pain as a Mediator of Depression. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20:5872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Polak D, Korkosz M, Guła Z. Sleep disorders in rheumatoid arthritis, axial spondyloarthritis and psoriatic arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2025;45:36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Qu H, Austin S, Singh JA. Identifying physician-perceived barriers to a pragmatic treatment trial in rheumatoid arthritis. Eur J Rheumatol. 2022;9:132-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Ren H, Lin F, Wu L, Tan L, Lu L, Xie X, Zhang Y, Bao Y, Ma Y, Huang X, Wang F, Jin Y. The prevalence and the effect of interferon -γ in the comorbidity of rheumatoid arthritis and depression. Behav Brain Res. 2023;439:114237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Ristic B, Carletto A, Fracassi E, Pacenza G, Zanetti G, Pistillo F, Cristofalo D, Bixio R, Bonetto C, Tosato S. Comparison and potential determinants of health-related quality of life among rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and spondyloarthritis: A cross-sectional study. J Psychosom Res. 2023;175:111512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Ryan S. Psychological and social needs of people with rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Nurs. 2023;32:280-282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Sacristán JA, Dilla T, Díaz-Cerezo S, Gabás-Rivera C, Aceituno S, Lizán L. Patient-physician discrepancy in the perception of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases: rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis. A qualitative systematic review of the literature. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0234705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Santos EJF, Farisogullari B, Dures E, Geenen R, Machado PM; EULAR taskforce on recommendations for the management of fatigue in people with inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Efficacy of non-pharmacological interventions: a systematic review informing the 2023 EULAR recommendations for the management of fatigue in people with inflammatory rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases. RMD Open. 2023;9:e003350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Schneider M, Baseler G, Funken O, Heberger S, Kiltz U, Klose P, Krüger K, Langhorst J, Mau W, Oltman R, Richter B, Seitz S, Sewerin P, Tholen R, Weseloh C, Witthöft M, Specker C. [Management of early rheumatoid arthritis : Interdisciplinary guideline]. Z Rheumatol. 2020;79:1-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Seizer L, Huber E, Schirmer M, Hilbert S, Wiest EM, Schubert C. Personalized therapy in rheumatoid arthritis (PETRA): a protocol for a randomized controlled trial to test the effect of a psychological intervention in rheumatoid arthritis. Trials. 2023;24:743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Sezgin MG, Bektas H. The effect of nurse-led care on fatigue in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled studies. J Clin Nurs. 2022;31:832-842. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Sharpe L, Richmond B, Todd J, Dudeney J, Dear BF, Szabo M, Sesel AL, Forrester M, Menzies RE. A cross-sectional study of existential concerns and fear of progression in people with Rheumatoid Arthritis. J Psychosom Res. 2023;175:111514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Shaw Y, Bradley M, Zhang C, Dominique A, Michaud K, McDonald D, Simon TA. Development of Resilience Among Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients: A Qualitative Study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020;72:1257-1265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Shen B, Li Y, Du X, Chen H, Xu Y, Li H, Xu GY. Effects of cognitive behavioral therapy for patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Health Med. 2020;25:1179-1191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Sibilia J, Berna F, Bloch JG, Scherlinger M. Mind-body practices in chronic inflammatory arthritis. Joint Bone Spine. 2024;91:105645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Siddle HJ, Chapman LS, Mankia K, Zăbălan C, Kouloumas M, Raza K, Falahee M, Kerry J, Kerschbaumer A, Aletaha D, Emery P, Richards SH. Perceptions and experiences of individuals at-risk of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) knowing about their risk of developing RA and being offered preventive treatment: systematic review and thematic synthesis of qualitative studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81:159-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Simons G, Janssen EM, Veldwijk J, DiSantostefano RL, Englbrecht M, Radawski C, Valor-Méndez L, Humphreys JH, Bruce IN, Hauber B, Raza K, Falahee M. Acceptable risks of treatments to prevent rheumatoid arthritis among first-degree relatives: demographic and psychological predictors of risk tolerance. RMD Open. 2022;8:e002593. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Singh G, Hamid A. Invalidation in fibromyalgia and rheumatoid arthritis and its effect on quality of life in Indian patients. Int J Rheum Dis. 2021;24:1047-1052. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Smolen JS. Rheumatoid arthritis Primer - behind the scenes. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2020;6:32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Husivargova A, Timkova V, Macejova Z, Kotradyova Z, Aljubouri MAS, Breznoscakova D, Sanderman R, Nagyova I. Social participation of rheumatoid arthritis patients: Does illness perception play a role? Health Psychol. 2024;43:269-279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Lahiri M, Cheung PPM, Dhanasekaran P, Wong SR, Yap A, Tan DSH, Chong SH, Tan CH, Santosa A, Phan P. Evaluation of a multidisciplinary care model to improve quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised controlled trial. Qual Life Res. 2022;31:1749-1759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Marr C, McDowell B, Holmes C, Edwards CJ, Cardwell C, McHenry M, Meenagh G, Teeling JL, McGuinness B. The RESIST Study: Examining Cognitive Change in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment Being Treated with a TNF-Inhibitor Compared to a Conventional Synthetic Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drug. J Alzheimers Dis. 2024;99:161-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Rutter-Locher Z, Kirkham BW, Bannister K, Bennett DL, Buckley CD, Taams LS, Denk F. An interdisciplinary perspective on peripheral drivers of pain in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2024;20:671-682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Zhou B, Wang G, Hong Y, Xu S, Wang J, Yu H, Liu Y, Yu L. Mindfulness interventions for rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2020;39:101088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | O'Leary H, Larkin L, Murphy GM, Quinn K. Relationship Between Pain and Sedentary Behavior in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2021;73:990-997. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Pinto AJ, Peçanha T, Meireles K, Benatti FB, Bonfiglioli K, de Sá Pinto AL, Lima FR, Pereira RMR, Irigoyen MCC, Turner JE, Kirwan JP, Owen N, Dunstan DW, Roschel H, Gualano B. A randomized controlled trial to reduce sedentary time in rheumatoid arthritis: protocol and rationale of the Take a STAND for Health study. Trials. 2020;21:171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Sparks JA, Malspeis S, Hahn J, Wang J, Roberts AL, Kubzansky LD, Costenbader KH. Depression and Subsequent Risk for Incident Rheumatoid Arthritis Among Women. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2021;73:78-89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Renard D, Tuffet S, Dieudé P, Claudepierre P, Gossec L, Fautrel B, Molto A, Miceli-Richard C, Richette P, Maheu E, Carette C, Czernichow S, Jamakorzyan C, Rousseau A, Berenbaum F, Beauvais C, Sellam J. Factors associated with dietary practices and beliefs on food of patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases: A multicentre cross-sectional study. Joint Bone Spine. 2025;92:105778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Theofanidis AH, Timkova V, Macejova Z, Kotradyova Z, Breznoscakova D, Sanderman R, Nagyova I. Pain in Biologic-Treated Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients: The Role of Illness Perception Before and After the COVID-19 Pandemic. Musculoskeletal Care. 2024;22:e1958. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Xu T, Jia X, Chen S, Xie Y, Tong KK, Iezzi T, Jackson T. Physical activity and sleep differences between osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis and non-arthritic people in China: objective versus self report comparisons. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Spijk-de Jonge MJ, Weijers JM, Teerenstra S, Elwyn G, van de Laar MA, van Riel PL, Huis AM, Hulscher ME. Patient involvement in rheumatoid arthritis care to improve disease activity-based management in daily practice: A randomized controlled trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2022;105:1244-1253. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Stoll N, Dey M, Norton S, Adas M, Bosworth A, Buch MH, Cope A, Lempp H, Galloway J, Nikiphorou E. Understanding the psychosocial determinants of effective disease management in rheumatoid arthritis to prevent persistently active disease: a qualitative study. RMD Open. 2024;10:e004104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Wróbel A, Barańska I, Szklarczyk J, Majda A, Jaworek J. Relationship between perceived stress, stress coping strategies, and clinical status in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2023;43:1665-1674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 106. | Sweeney M, Adas MA, Cope A, Norton S. Longitudinal effects of affective distress on disease outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Rheumatol Int. 2024;44:1421-1433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 107. | Szewczyk D, Sadura-Sieklucka T, Sokołowska B, Księżopolska-Orłowska K. Improving the quality of life of patients with rheumatoid arthritis after rehabilitation irrespective of the level of disease activity. Rheumatol Int. 2021;41:781-786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 108. | Tański W, Dudek K, Adamowski T. Work Ability and Quality of Life in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:13260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 109. | Taylor PC, Woods M, Rycroft C, Patel P, Blanthorn-Hazell S, Kent T, Bukhari M. Targeted literature review of current treatments and unmet need in moderate rheumatoid arthritis in the United Kingdom. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60:4972-4981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 110. | Termine M, Davidson Z, Choi T, Leech M. What do we know about dietary perceptions and beliefs of patients with rheumatoid arthritis? A scoping review. Rheumatol Int. 2024;44:1861-1874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 111. | Walrabenstein W, van der Leeden M, Weijs P, van Middendorp H, Wagenaar C, van Dongen JM, Nieuwdorp M, de Jonge CS, van Boheemen L, van Schaardenburg D. The effect of a multidisciplinary lifestyle program for patients with rheumatoid arthritis, an increased risk for rheumatoid arthritis or with metabolic syndrome-associated osteoarthritis: the "Plants for Joints" randomized controlled trial protocol. Trials. 2021;22:715. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 112. | Walrabenstein W, Wagenaar CA, van der Leeden M, Turkstra F, Twisk JWR, Boers M, van Middendorp H, Weijs PJM, van Schaardenburg D. A multidisciplinary lifestyle program for rheumatoid arthritis: the 'Plants for Joints' randomized controlled trial. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2023;62:2683-2691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 113. | Deniz O, Cavusoglu C, Satis H, Salman RB, Varan O, Atas N, Coteli S, Dogrul RT, Babaoglu H, Oncul A, Varan HD, Kizilarslanoglu MC, Tufan A, Goker B. Sleep quality and its associations with disease activity and quality of life in older patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Eur Geriatr Med. 2023;14:317-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 114. | Duarte C, Spilker RLF, Paiva C, Ferreira RJO, da Silva JAP, Pinto AM. MITIG.RA: study protocol of a tailored psychological intervention for managing fatigue in rheumatoid arthritis randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2023;24:651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 115. | Wells I, Zemedikun DT, Simons G, Stack RJ, Mallen CD, Raza K, Falahee M. Predictors of interest in predictive testing for rheumatoid arthritis among first degree relatives of rheumatoid arthritis patients. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2022;61:3223-3233. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 116. | Wenger A, Calabrese P. Comparing underlying mechanisms of depression in multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis. J Integr Neurosci. 2021;20:765-776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 117. | Wilantri S, Grasshoff H, Lange T, Gaber T, Besedovsky L, Buttgereit F. Detecting and exploiting the circadian clock in rheumatoid arthritis. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2023;239:e14028. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 118. | Wilk M, Łosińska K, Pripp AH, Korkosz M, Haugeberg G. Pain catastrophizing in rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis and axial spondyloarthritis: biopsychosocial perspective and impact on health-related quality of life. Rheumatol Int. 2022;42:669-682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 119. | Zhang L, Cai P, Zhu W. Depression has an impact on disease activity and health-related quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Rheum Dis. 2020;23:285-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 120. | Ledón-LLanes L, Contreras-Yáñez I, Guaracha-Basáñez G, Valverde-Hernández SS, González-Marín A, Ballinas-Sánchez ÁJ, Durand M, Pascual-Ramos V. Views of Mexican outpatients with rheumatoid arthritis on sexual and reproductive health: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0245538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 121. | Liu T, Geng Y, Han Z, Qin W, Zhou L, Ding Y, Zhang Z, Sun G. Self-reported sleep disturbance is significantly associated with depression, anxiety, self-efficacy, and stigma in Chinese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Psychol Health Med. 2023;28:908-916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 122. | Pencheva DT, Heaney A, McKenna SP, Monov SV. Adaptation and validation of the Rheumatoid Arthritis Quality of Life (RAQoL) questionnaire for use in Bulgaria. Rheumatol Int. 2020;40:2077-2083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 123. | Yazdi F, Shakibi MR, Gharavi Roudsari E, Nakhaee N, Salajegheh P. The effect of suffering from rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and back pain on sexual functioning and marital satisfaction in Iran. Int J Rheum Dis. 2021;24:373-379. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 124. | Kwiatkowska B, Kłak A, Maślińska M, Mańczak M, Raciborski F. Factors of depression among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Reumatologia. 2018;56:219-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 125. | Zhou J, Fan X, Gan Y, Luo Z, Qi H, Cao Y. Effect of fatigue on quality of life in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: the chain mediating role of resilience and self-efficacy. Adv Rheumatol. 2024;64:66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 126. | Feasibility and Acceptability of a Self-Management Program for Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis. Orthop Nurs. 2020;39:246-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 127. | Bounabe A, Elammare S, Janani S, Ouabich R, Elarrachi I. Effectiveness of patient education on the quality of life of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2024;69:152569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 128. | Fernandes M, Figueiredo A, Oliveira AL, Ferreira AC, Mendonça P, Taulaigo AV, Vicente M, Fanica MJ, Ruano C, Panarra A, Mateus C, Moraes-Fontes MF. Biological Therapy in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis in a Tertiary Center in Portugal: A Cross-Sectional Study. Acta Med Port. 2021;34:362-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 129. | Giblon RE, Achenbach SJ, Myasoedova E, Davis JM 3rd, Kronzer VL, Bobo WV, Crowson CS. Trends in Anxiety and Depression Among Individuals With Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Population-Based Study. J Rheumatol. 2025;52:210-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 130. | Roodenrijs NMT, Welsing PMJ, van der Goes MC, Tekstra J, Lafeber FPJG, Jacobs JWG, van Laar JM. Healthcare utilization and economic burden of difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis: a cost-of-illness study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60:4681-4690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 131. | Shao JH, Yu KH, Chen SH. Feasibility and Acceptability of a Self-Management Program for Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis. Orthop Nurs. 2020;39:238-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 132. | Lopez-Olivo MA, Zogala RJ, des Bordes J, Zamora NV, Christensen R, Rai D, Goel N, Carmona L, Pratt G, Strand V, Suarez-Almazor ME. Outcomes Reported in Prospective Long-Term Observational Studies and Registries of Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis Worldwide: An Outcome Measures in Rheumatology Systematic Review. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2021;73:649-657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 133. |