Published online Jan 19, 2026. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v16.i1.110146

Revised: August 17, 2025

Accepted: October 24, 2025

Published online: January 19, 2026

Processing time: 196 Days and 20.7 Hours

Low anterior resection syndrome (LARS) is a prevalent and debilitating com

To investigate the therapeutic effect of electroacupuncture on emotional recovery and gastrointestinal function in patients with moderate to severe LARS, and to explore its potential advantages in psychologically vulnerable subgroups.

We conducted a retrospective, controlled study involving 100 patients with moderate to severe LARS (LARS score ≥ 21) treated at two tertiary hospitals in China between January 2022 and December 2024. Patients received either standard postoperative care alone (n = 50) or in combination with a standardized 4-week electroacupuncture protocol (n = 50). Psychological and functional outcomes were assessed using validated instruments including Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Body Image Scale (BIS), General Self-Efficacy Scale, Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS), LARS score, and European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 at four time points. The primary endpoint was emotional remission, defined as a ≥ 3-point reduction in HADS-Anxiety subscale (HADS-A). Analyses included repeated-measures comparisons, Kaplan-Meier survival curves, Cox regression models, and subgroup-interaction testing.

At baseline, demographic, surgical, and psychosocial characteristics were comparable among groups. By week 4, patients receiving electroacupuncture demonstrated significantly greater reductions in anxiety (HADS-A: 4.8 ± 2.6 vs 7.3 ± 3.0; P < 0.001), depression, and body-image disturbance (BIS: 8.7 ± 3.6 vs 11.9 ± 4.2; P < 0.001), alongside enhanced coping capacity (Brief Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced), perceived social support (PSSS), and bowel function (LARS score). Emotional remission - defined as a ≥ 3-point HADS-A reduction - was achieved more rapidly in the electroacupuncture group, as confirmed by Kaplan-Meier analysis (log-rank P < 0.001; odds ratio = 4.7). Multivariate Cox regression identified higher baseline LARS and BIS scores as independent predictors of delayed emotional recovery. Subgroup analyses revealed significantly amplified treatment benefits in patients with high baseline anxiety (HADS-A ≥ 8), elevated body-image disturbance (BIS ≥ 12), or low perceived social support (PSSS < 60), with consistent interaction effects (P for interaction < 0.05 across subgroups).

Electroacupuncture may accelerate emotional recovery and improve functional and psychosocial outcomes in patients with LARS. Its integration into postoperative care may offer particular benefits for psychologically vul

Core Tip: Low anterior resection syndrome impairs both bowel function and emotional health after rectal cancer surgery. This controlled study shows that electroacupuncture significantly improves anxiety, depression, body image, and bowel symptoms. Emotional remission occurred faster in the electroacupuncture group, especially among patients with high psychological burden. The findings support electroacupuncture as a safe, multidimensional approach for low anterior resection syndrome rehabilitation and highlight the value of targeted psychosocial interventions in colorectal cancer survivorship care.

- Citation: Wang N, Yang Y, Li SS, Wang XF. Electroacupuncture improves psychosocial outcomes in rectal cancer patients with bowel dysfunction. World J Psychiatry 2026; 16(1): 110146

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v16/i1/110146.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v16.i1.110146

Low anterior resection syndrome (LARS) is a common and debilitating complication following sphincter-preserving surgery for rectal cancer, affecting up to 80% of patients postoperatively[1]. Characterized by a constellation of symptoms including urgency, frequency, clustering, and incontinence, LARS severely compromises bowel control and undermines quality of life, even in the absence of oncologic recurrence[2]. Despite advances in surgical techniques and enhanced recovery protocols, bowel dysfunction persists in a substantial proportion of patients long after stoma reversal[3]. Not

The psychological burden associated with LARS, although increasingly being recognized, remains insufficiently addressed in clinical practice and research. A growing body of literature has identified elevated rates of anxiety, dep

Electroacupuncture, a modality rooted in traditional Chinese medicine and increasingly integrated into modern neurorehabilitation, has shown promise in modulating gastrointestinal and emotional symptoms via central-peripheral neurohumoral pathways[12,13]. Experimental studies suggest that electroacupuncture may regulate gut-brain axis signaling, enhance vagal tone, and attenuate limbic system hyperactivity, thereby influencing both autonomic function and emotional regulation[14]. In clinical contexts, electroacupuncture has been employed as an adjunct for postoperative pain, chemotherapy-induced gastrointestinal toxicity, and functional bowel disorders, with favorable safety and acceptability profiles[15]. Notably, pilot trials in cancer rehabilitation have demonstrated improvements in anxiety, sleep quality, and visceral discomfort, though rigorous evidence in the setting of LARS remains sparse. Given its dual-action potential - targeting both neuromotor dysfunction and psychological distress - electroacupuncture presents as a biologically plausible, low-risk intervention for patients with persistent LARS symptoms and emotional comorbidity[14,16,17].

In light of the dual burden of functional and psychological sequelae experienced by patients with LARS - and the lack of integrative, evidence-based interventions addressing this overlap - there is a critical need to evaluate therapeutic strategies that concurrently target emotional recovery and bowel function. Given its plausible mechanisms, favorable safety profile, and cultural acceptability in East Asian populations, electroacupuncture warrants systematic investigation in this setting. Electroacupuncture protocols typically target specific acupoints based on both traditional meridian theory and emerging neurophysiological evidence. In this study, we selected Zusanli (ST36), a point known to enhance gastrointestinal motility and vagal activity, and Zhongliao (BL33), which is anatomically located near the sacral nerves and implicated in modulating pelvic autonomic reflexes. These acupoints are believed to influence gut-brain axis signaling by affecting parasympathetic tone, visceral sensitivity, and neuroendocrine pathways. Such mechanisms may provide a biologically plausible rationale for addressing both bowel dysfunction and emotional dysregulation in patients with LARS. Therefore, we conducted a controlled retrospective study to assess the impact of electroacupuncture on psychological adaptation, functional recovery, and quality of life among patients with moderate to severe LARS following rectal cancer surgery. We further aimed to identify predictors of emotional remission and explore potential heterogeneity in treatment response across psychological risk subgroups.

This retrospective controlled study was conducted at two tertiary academic hospitals in China: Peking University Lu’an Hospital (Changzhi), and Guang’anmen Hospital, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences (Beijing). Consecutive patients diagnosed with LARS following sphincter-preserving surgery for rectal cancer were included. Clinical data were collected from medical records and structured follow-up evaluations conducted between January 2022 and December 2024. Eligible patients were divided into two groups based on the postoperative rehabilitation strategy received: An electroacupuncture group and a standard care (control) group.

Patients were eligible if they met the following inclusion criteria: (1) Age between 18 and 80 years; (2) A confirmed history of rectal adenocarcinoma treated with sphincter-preserving low anterior resection; (3) A postoperative interval of ≥ 6 months; (4) Diagnosed with moderate to severe LARS, defined as a LARS score ≥ 21; and (5) Completion of baseline psychological assessments including Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Body Image Scale (BIS), General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES), and Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS). Exclusion criteria included: (1) Evidence of tumor recurrence or metastatic disease; (2) Previous pelvic radiotherapy or neurological conditions affecting bowel function; (3) Concurrent participation in other rehabilitation or psychotherapeutic interventions; (4) Severe comorbid psychiatric disorders; and (5) Incomplete follow-up data.

Patients were allocated to the electroacupuncture or control group based on clinical rehabilitation plans determined by the attending physician and patient preference, as this was a non-randomized, retrospective analysis. All participants received standard postoperative management; only the intervention group received additional electroacupuncture therapy.

Patients in the electroacupuncture group received standardized electroacupuncture therapy in addition to routine postoperative care. Treatment was administered by licensed acupuncturists with > 5 years of clinical experience and was based on contemporary clinical guidelines for postoperative pelvic floor dysfunction in colorectal surgery. Acupuncture points included ST36, Shangjuxu (ST37), BL33, Huiyang (BL35), and Zigong (EX-CA1). Disposable sterile needles (0.30 mm × 40 mm) were inserted to a depth of 25-35 mm and connected to a G6805-II electroacupuncture device (Qingdao Xinsheng Industries Co., Ltd., China) with continuous wave stimulation at 20 Hz for 30 minutes per session. Treatment was delivered five times per week for the first 2 weeks, followed by three sessions per week for the subsequent 2 weeks, totaling 4 weeks (14 sessions). Patient compliance was monitored through treatment logs, and any adverse events (e.g., dizziness, local discomfort, or treatment refusal) were recorded and managed per protocol. The control group received routine postoperative care, including dietary guidance, bowel training, and psychological support as per institutional protocol, but no acupuncture or invasive procedures. These points were selected based on anatomical and clinical evidence supporting their involvement in vagal and sacral neuromodulation.

The primary outcome was emotional remission, defined as a reduction of ≥ 3 points in the HADS Anxiety subscale (HADS-A), a widely validated 7-item scale (range 0-21), with higher scores indicating more severe anxiety symptoms. Secondary outcomes included changes in: HADS-Depression subscale (range 0-21); BIS, a 10-item measure of body image disturbance (range 0-30), with higher scores reflecting greater concern; GSES, assessing confidence in self-management (range 10-40); PSSS (range 12-84), with higher scores indicating better perceived support; Brief Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced Inventory, a 14-item measure of coping styles (range 14-56); LARS score, a validated 5-item functional assessment tool for bowel dysfunction [range 0-42; categorized as no (0-20), minor (21-29), or major LARS (30-42)]; European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (EORTC QLQ-C30), assessing health-related quality of life in cancer patients. Global health status and two functional domains - emotional and social functioning - were selected for analysis (scored 0-100, with higher scores indicating better function).

All assessments were performed at four time points: Baseline (prior to intervention), week 1, week 2, and week 4. Instruments were administered through in-person interviews by trained research nurses using standardized, validated Chinese-language versions of each scale.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline demographic, clinical, and psychosocial characteristics. Continuous variables were reported as means ± SD and compared using independent-samples t tests or Mann-Whitney U tests based on data distribution. Categorical variables were expressed as counts (percentages) and compared using χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests as appropriate. For longitudinal outcomes, repeated measures of psychological and functional variables at week 0, week 1, week 2, and week 4 were compared between groups using independent t tests at each time point. The primary endpoint - emotional remission (≥ 3-point reduction in HADS-A score) - was evaluated using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, with log-rank tests used to compare time-to-event distributions between groups. Cox proportional hazards models were constructed to identify independent predictors of time to emotional remission, reporting hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Variables included in the multivariate models were selected based on clinical relevance and univariate P-values < 0.10.

Two hierarchical Cox models were developed: Model 1 adjusted for age, sex, and body mass index; model 2 further adjusted for baseline LARS score, BIS, GSES, and PSSS. Interaction terms and stratified subgroup analyses were performed to examine heterogeneity in treatment effect across psychological risk strata (e.g., high vs low baseline anxiety or body image disturbance). Given the exploratory nature of these subgroup analyses, no formal correction for multiple comparisons (e.g., Bonferroni or false discovery rate adjustment) was applied. As such, findings should be interpreted as hypothesis-generating rather than confirmatory. To partially address confounding bias inherent in retrospective studies, multivariate models were carefully constructed based on clinical rationale and baseline imbalances. Although propensity score matching and sensitivity analyses were not applied in this study, their absence is acknowledged and discussed as a methodological limitation. Although multiple testing correction was not applied, subgroup results were interpreted cautiously as hypothesis-generating.

All statistical tests were two-sided, and P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were conducted using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp., NY, United States) and R version 4.2.2.

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (2013 revision) and followed national and institutional regulations governing research involving human participants. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Peking University Lu’an Hospital (Approval No. 2021009) and Guang’anmen Hospital, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences (Approval No. 2022-037-KY-01) prior to study initiation.

Given the retrospective nature of data collection and the use of anonymized medical records, written informed consent was waived. All patient data were de-identified before analysis to ensure confidentiality. Access to original medical records and patient-reported outcomes was restricted to authorized research personnel only, and all data were stored on secure institutional servers.

A total of 100 patients diagnosed with LARS following sphincter-preserving rectal cancer surgery were included, with 50 patients in the electroacupuncture group and 50 in the control group. As shown in Table 1, the two groups were well-balanced in demographic and clinical parameters. The mean age was 61.2 ± 8.5 years in the electroacupuncture group and 62.1 ± 7.9 years in the control group (t = 0.641, P = 0.523). No significant differences were observed in sex distribution (χ2 = 0.168, P = 0.682), body mass index (t = 0.685, P = 0.497), education level (χ2 = 0.202, P = 0.653), or employment status (χ2 = 0.158, P = 0.691). Surgical and oncological variables - including tumor-nodes-metastasis staging (χ2 = 0.410, P = 0.815), time since surgery (t = 0.567, P = 0.571), anastomosis level (t = 0.779, P = 0.438), and laparoscopic approach rate (χ2 = 0.319, P = 0.573) - were also comparable between groups.

| Characteristics | Electroacupuncture group (n = 50) | Control group (n = 50) | Test statistic1 | P value2 |

| Demographic variables | ||||

| Age, years | 61.2 ± 8.5 | 62.1 ± 7.9 | t = 0.641 | 0.523 |

| Sex | χ2 = 0.168 | 0.682 | ||

| Male | 30 (60) | 28 (56) | ||

| Female | 20 (40) | 22 (44) | ||

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 23.7 ± 3.2 | 24.1 ± 3.5 | t = 0.685 | 0.497 |

| Education level ≥ high school | 38 (76) | 36 (72) | χ2 = 0.202 | 0.653 |

| Employment status | χ2 = 0.158 | 0.691 | ||

| Employed | 29 (58) | 27 (54) | ||

| Unemployed | 21 (42) | 23 (46) | ||

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypertension | 17 (34) | 19 (38) | χ2 = 0.164 | 0.685 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 10 (20) | 9 (18) | χ2 = 0.072 | 0.791 |

| Smoking history | 12 (24) | 14 (28) | χ2 = 0.214 | 0.644 |

| Surgical and oncological characteristics | ||||

| TNM stage | χ2 = 0.410 | 0.815 | ||

| Stage I | 8 (16) | 7 (14) | ||

| Stage II | 26 (52) | 24 (48) | ||

| Stage III | 16 (32) | 19 (38) | ||

| Time since surgery, months | 10.3 ± 4.1 | 10.8 ± 4.4 | t = 0.567 | 0.571 |

| Anastomosis level from anal verge, cm | 5.1 ± 0.8 | 5.2 ± 0.9 | t = 0.779 | 0.438 |

| Type of surgery | χ2 = 0.319 | 0.573 | ||

| Laparoscopic | 43 (86) | 41 (82) | ||

| Open | 7 (14) | 9 (18) | ||

| Neoadjuvant radiotherapy | 18 (36) | 20 (40) | χ2 = 0.170 | 0.684 |

| Functional status | ||||

| LARS score (0-42) | 32.4 ± 5.6 | 31.9 ± 5.9 | t = 0.426 | 0.672 |

| LARS severity category | χ2 = 0.040 | 0.842 | ||

| Moderate (21-29) | 22 (44) | 21 (42) | ||

| Severe (≥ 30) | 28 (56) | 29 (58) | ||

| Baseline quality of life (EORTC QLQ-C30 total) | 56.3 ± 8.9 | 57.0 ± 9.1 | t = 0.437 | 0.664 |

| Psychological characteristics | ||||

| Anxiety score (HADS-A, 0-21) | 8.1 ± 3.2 | 8.5 ± 3.5 | t = 0.610 | 0.544 |

| Depression score (HADS-D, 0-21) | 7.6 ± 3.4 | 7.9 ± 3.7 | t = 0.427 | 0.671 |

| General self-efficacy (GSES, 10-40) | 28.2 ± 4.5 | 27.6 ± 5.1 | t = 0.692 | 0.493 |

| Perceived social support (PSSS, 12-84) | 59.4 ± 8.9 | 58.1 ± 9.5 | t = 0.796 | 0.428 |

| Coping strategy score (Brief COPE, 14-56) | 38.5 ± 6.1 | 37.9 ± 6.4 | t = 0.561 | 0.577 |

| Body image disturbance (BIS, 0-30) | 12.7 ± 4.3 | 13.1 ± 4.7 | t = 0.460 | 0.649 |

Functional and psychosocial status at baseline revealed no statistical differences. The mean LARS score was 32.4 ± 5.6 and 31.9 ± 5.9 in the intervention and control groups, respectively (t = 0.426, P = 0.672). Quality of life scores (EORTC QLQ-C30) were similar between groups (t = 0.437, P = 0.664), as were measures of anxiety, depression, self-efficacy, social support, coping strategy, and body image disturbance, with all P-values exceeding 0.4. A correlation heatmap of continuous variables (Figure 1) further illustrated the interrelationships among demographic, clinical, and psychological dimensions, revealing moderate positive associations between LARS severity and depression (r = 0.41), and inverse correlations between quality of life and both anxiety and BIS scores.

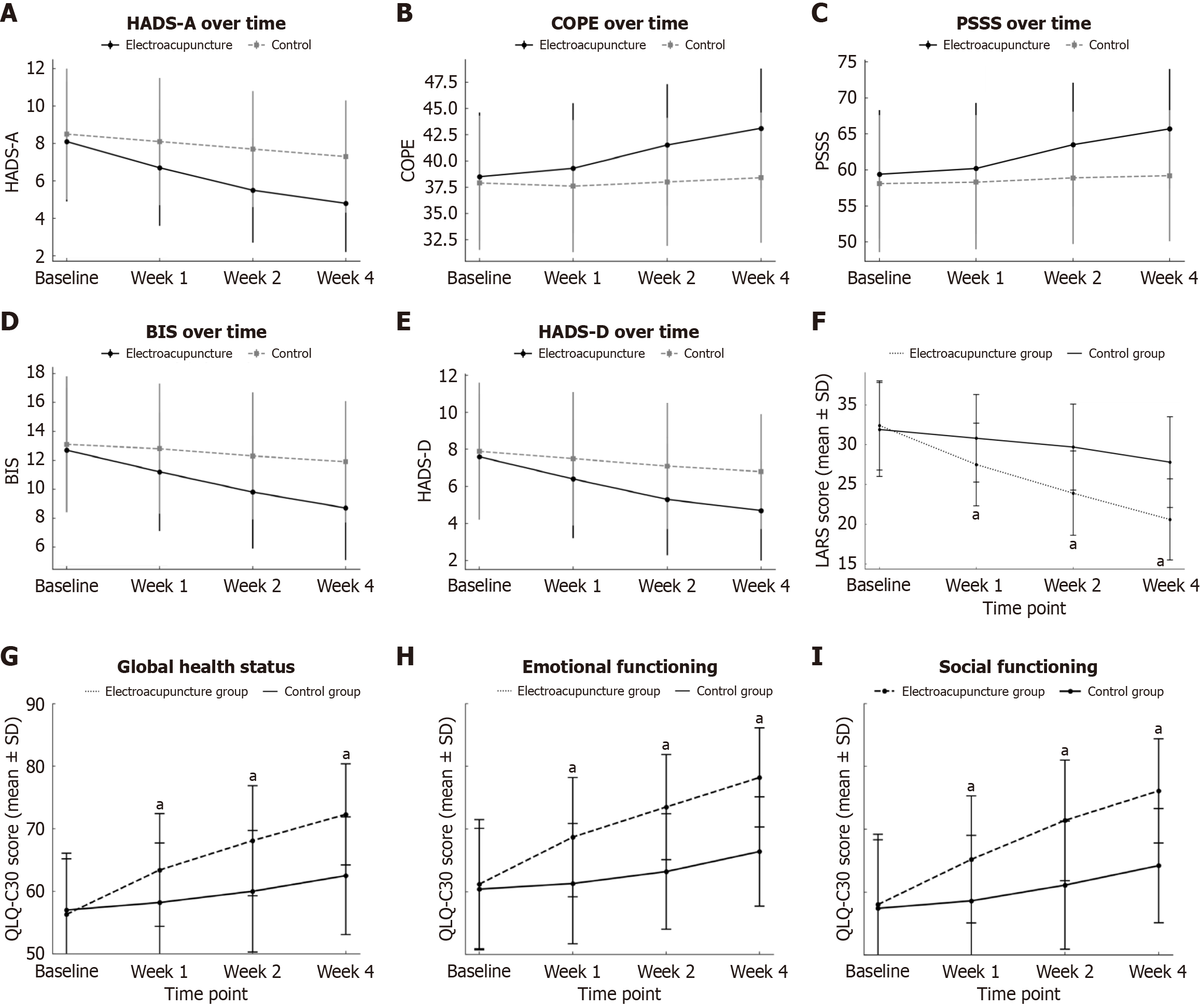

At baseline, no significant differences were observed between the electroacupuncture and control groups in any of the psychological measures, including anxiety (HADS-A: 8.1 ± 3.2 vs 8.5 ± 3.5; P = 0.547), depression (HADS-Depression subscale: 7.6 ± 3.4 vs 7.9 ± 3.7; P = 0.671), body image disturbance (BIS: 12.7 ± 4.3 vs 13.1 ± 4.7; P = 0.649), coping strategy (Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced: 38.5 ± 6.1 vs 37.9 ± 6.4; P = 0.577), and perceived social support (PSSS: 59.4 ± 8.9 vs 58.1 ± 9.5; P = 0.428; Table 2). From week 2 onward, the electroacupuncture group showed significantly greater improvements in anxiety (week 4: 4.8 ± 2.6 vs 7.3 ± 3.0; P < 0.001) and depression scores (week 4: 4.7 ± 2.7 vs 6.8 ± 3.1; P < 0.001). Body image disturbance also improved more markedly in the electroacupuncture group by week 4 (8.7 ± 3.6 vs 11.9 ± 4.2; P < 0.001). Similar trends were observed in coping strategy scores, which increased significantly in the intervention group (week 4: 43.1 ± 5.7 vs 38.4 ± 6.2; P < 0.001). Perceived social support showed a statistically significant between-group difference from week 2 onward (week 4: 65.7 ± 8.3 vs 59.2 ± 9.1; P < 0.001). Temporal changes across all psychological domains are illustrated in Figure 2A-E.

| Psychological measure | Time point | Electroacupuncture group (n = 50) | Control group (n = 50) | Test statistic1 | P value2 |

| Anxiety (HADS-A, 0-21) | Baseline | 8.1 ± 3.2 | 8.5 ± 3.5 | U = 1189.0 | 0.547 |

| Week 1 | 6.7 ± 3.1 | 8.1 ± 3.4 | U = 941.0 | 0.042 | |

| Week 2 | 5.5 ± 2.8 | 7.7 ± 3.1 | U = 778.5 | < 0.001 | |

| Week 4 | 4.8 ± 2.6 | 7.3 ± 3.0 | U = 658.0 | < 0.001 | |

| Depression (HADS-D, 0-21) | Baseline | 7.6 ± 3.4 | 7.9 ± 3.7 | U = 1202.5 | 0.671 |

| Week 1 | 6.4 ± 3.2 | 7.5 ± 3.6 | U = 1021.0 | 0.102 | |

| Week 2 | 5.3 ± 3.0 | 7.1 ± 3.4 | U = 854.0 | 0.005 | |

| Week 4 | 4.7 ± 2.7 | 6.8 ± 3.1 | U = 722.0 | < 0.001 | |

| Body image disturbance (BIS, 0-30) | Baseline | 12.7 ± 4.3 | 13.1 ± 4.7 | U = 1224.5 | 0.649 |

| Week 1 | 11.2 ± 4.1 | 12.8 ± 4.5 | U = 1034.0 | 0.078 | |

| Week 2 | 9.8 ± 3.9 | 12.3 ± 4.4 | U = 876.0 | 0.003 | |

| Week 4 | 8.7 ± 3.6 | 11.9 ± 4.2 | U = 725.5 | < 0.001 | |

| Coping strategy (Brief COPE, 14-56) | Baseline | 38.5 ± 6.1 | 37.9 ± 6.4 | t = 0.561 | 0.577 |

| Week 1 | 39.3 ± 6.2 | 37.6 ± 6.3 | t = 1.390 | 0.169 | |

| Week 2 | 41.5 ± 5.8 | 38.0 ± 6.1 | t = 3.067 | 0.003 | |

| Week 4 | 43.1 ± 5.7 | 38.4 ± 6.2 | t = 4.114 | < 0.001 | |

| Social support (PSSS, 12-84) | Baseline | 59.4 ± 8.9 | 58.1 ± 9.5 | t = 0.796 | 0.428 |

| Week 1 | 60.2 ± 9.1 | 58.3 ± 9.3 | t = 1.007 | 0.316 | |

| Week 2 | 63.5 ± 8.6 | 58.9 ± 9.2 | t = 2.642 | 0.010 | |

| Week 4 | 65.7 ± 8.3 | 59.2 ± 9.1 | t = 3.584 | < 0.001 |

At baseline, no significant difference in LARS scores was observed between the electroacupuncture group (32.4 ± 5.6) and the control group (31.9 ± 5.9; t = 0.43, P = 0.672). From week 1 onward, the electroacupuncture group exhibited significantly lower LARS scores compared to controls (week 1: 27.5 ± 5.2 vs 30.8 ± 5.5; t = 2.44, P = 0.018; week 4: 20.6 ± 5.1 vs 27.8 ± 5.7; t = 6.79, P < 0.001), indicating consistent functional improvement over time (Figure 2F; Table 3).

Quality of life, as measured by the EORTC QLQ-C30, also improved significantly in the electroacupuncture group across multiple domains. Global health status increased from 56.3 ± 8.9 at baseline to 72.3 ± 8.1 at week 4, compared to 62.5 ± 9.4 in the control group (t = -5.66, P < 0.001). Emotional functioning (78.2 ± 7.9 vs 66.4 ± 8.7; t = -6.90, P < 0.001) and social functioning (76.1 ± 8.3 vs 64.2 ± 9.1; t = -6.73, P < 0.001) also showed statistically significant between-group differences at week 4 (Figure 2G-I;Table 4).

| Time point | Domain | Electroacupuncture group | Control group | t value | P value |

| Baseline | Global health status | 56.3 ± 8.9 | 57.0 ± 9.1 | 0.44 | 0.664 |

| Emotional functioning | 61.2 ± 10.3 | 60.4 ± 9.7 | -0.38 | 0.702 | |

| Social functioning | 58.0 ± 11.2 | 57.4 ± 10.9 | -0.24 | 0.813 | |

| Week 1 | Global health status | 63.4 ± 9.0a | 58.2 ± 9.5 | -2.49 | 0.015 |

| Emotional functioning | 68.7 ± 9.5a | 61.3 ± 9.6 | -2.84 | 0.006 | |

| Social functioning | 65.2 ± 10.1a | 58.6 ± 10.4 | -2.72 | 0.009 | |

| Week 2 | Global health status | 68.1 ± 8.8a | 60.0 ± 9.7 | -4.17 | < 0.001 |

| Emotional functioning | 73.5 ± 8.4a | 63.2 ± 9.2 | -5.67 | < 0.001 | |

| Social functioning | 71.4 ± 9.6a | 61.1 ± 10.2 | -5.02 | < 0.001 | |

| Week 4 | Global health status | 72.3 ± 8.1a | 62.5 ± 9.4 | -5.66 | < 0.001 |

| Emotional functioning | 78.2 ± 7.9a | 66.4 ± 8.7 | -6.90 | < 0.001 | |

| Social functioning | 76.1 ± 8.3a | 64.2 ± 9.1 | -6.73 | < 0.001 |

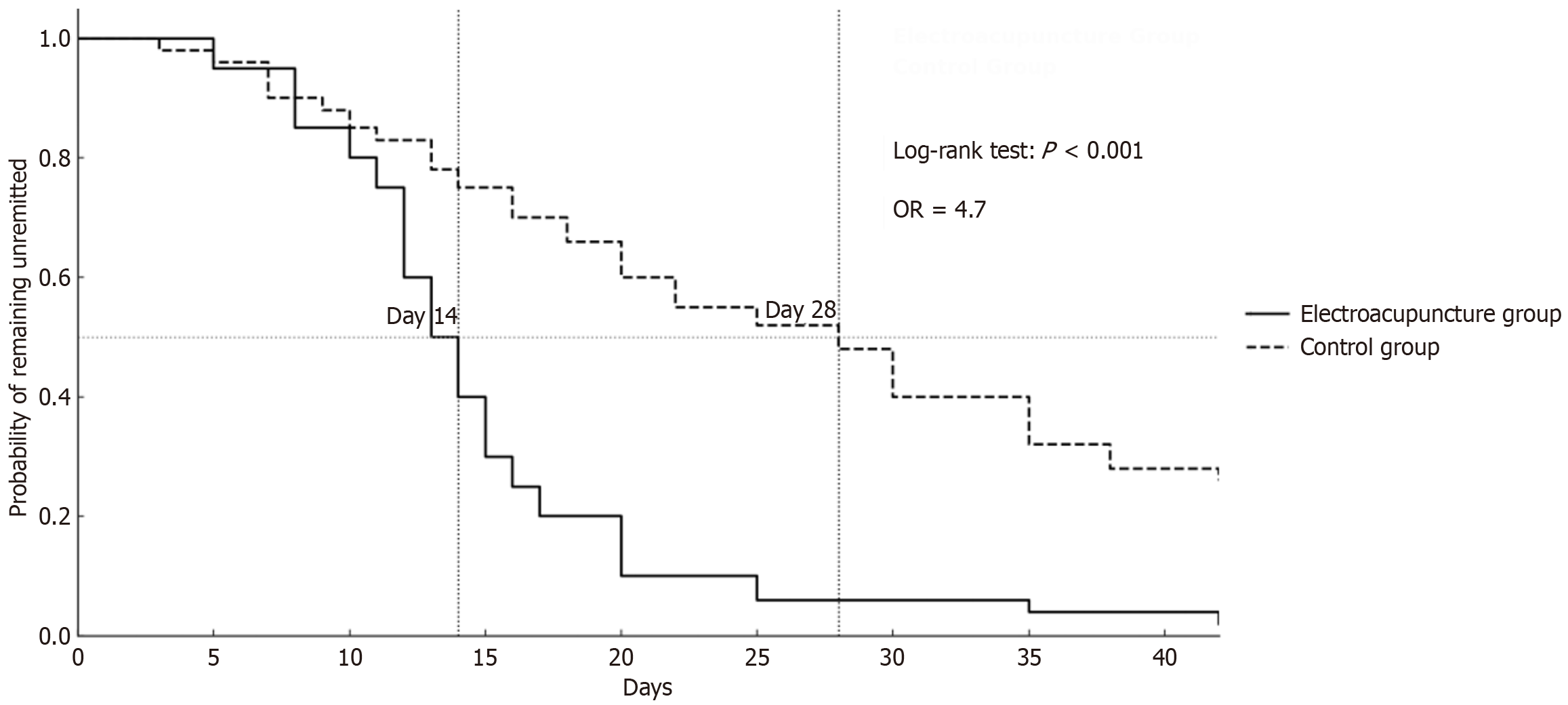

Time-to-event analysis was performed to compare the onset of emotional improvement, defined as a ≥ 3-point reduction in HADS-A scores. The Kaplan-Meier survival curves indicated a significantly shorter time to emotional response in the electroacupuncture group compared to the control group (log-rank test: P < 0.001). By day 14, more than 50% of patients in the electroacupuncture group had achieved clinical improvement, whereas the median response time in the control group extended beyond day 28 (Figure 3). The odds of achieving emotional remission within 4 weeks were significantly higher in the electroacupuncture group (odds ratio = 4.7).

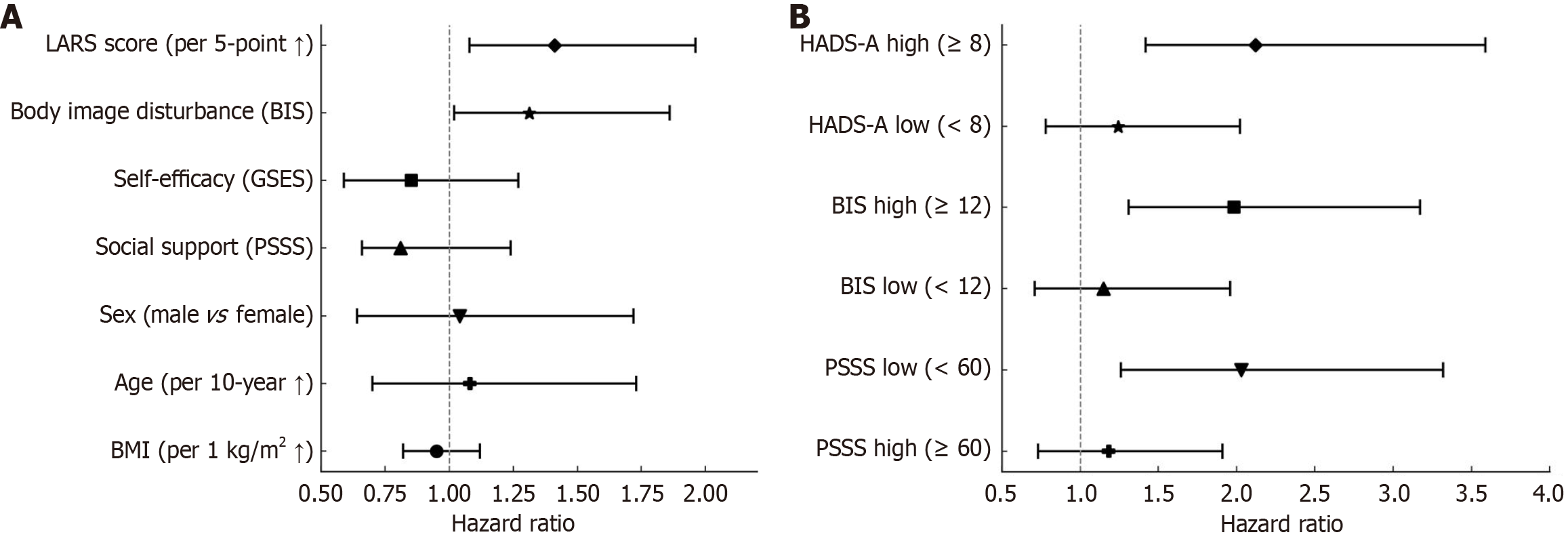

Univariate Cox regression analysis identified several predictors of time to emotional remission, defined as a reduction of ≥ 3 points in HADS-A scores. Higher baseline LARS scores (HR = 1.36, 95%CI: 0.87-2.14, P = 0.008), greater body image disturbance (BIS; HR = 1.27, 95%CI: 0.81-1.99, P = 0.034), and lower social support (PSSS; HR = 0.80, 95%CI: 0.51-1.26, P = 0.048) were associated with delayed emotional recovery. Self-efficacy (GSES) showed a borderline effect (HR = 0.84, P = 0.061), whereas demographic and surgical factors were not significantly associated (Table 5). In the multivariate analysis adjusting for sex, age, and body mass index (model 1), LARS score and BIS remained consistent predictors. In the fully adjusted model (model 2), higher LARS scores (HR = 1.41, 95%CI: 1.08-1.96, P = 0.016) and BIS (HR = 1.31, 95%CI: 1.02-1.86, P = 0.037) were independently associated with slower emotional remission (Figure 4A; Table 6). Other variables, including GSES and PSSS, did not retain statistical significance after full adjustment.

| Variable | β coefficient1 | HR (95%CI) | P value |

| LARS score (per 5-point increase) | 0.31 | 1.36 (0.87-2.14) | 0.008 |

| Body image disturbance (BIS, per 5-point increase) | 0.24 | 1.27 (0.81-1.99) | 0.034 |

| Self-efficacy (GSES, per 5-point increase) | -0.18 | 0.84 (0.53-1.31) | 0.061 |

| Social support (PSSS, per 5-point increase) | -0.22 | 0.80 (0.51-1.26) | 0.048 |

| Time since surgery (≤ 12 months vs > 12 months) | 0.12 | 1.13 (0.72-1.77) | 0.290 |

| Surgical approach (open vs laparoscopic) | -0.05 | 0.95 (0.61-1.47) | 0.711 |

| Age (per 10-year increase) | 0.07 | 1.07 (0.69-1.67) | 0.518 |

| Sex (male vs female) | 0.03 | 1.03 (0.65-1.65) | 0.889 |

| BMI (per 1 kg/m2 increase) | -0.04 | 0.96 (0.83-1.12) | 0.634 |

| HADS-D baseline (per 3-point increase) | 0.16 | 1.17 (0.92-1.51) | 0.141 |

| Brief COPE (per 5-point increase) | -0.09 | 0.91 (0.71-1.17) | 0.456 |

| Educational level (high school or below vs college or above) | 0.14 | 1.15 (0.73-1.81) | 0.553 |

| Employment status (unemployed vs employed) | -0.08 | 0.92 (0.58-1.47) | 0.724 |

| Model | LARS score (per 5-point increase) | Body image disturbance (BIS; per 5-point increase) | Self-efficacy (GSES; per 5-point increase) | Social support (PSSS; per 5-point increase) | Sex (male vs female) | Age (per 10-year increase) | BMI (per 1 kg/m2 increase) |

| Unadjusted | |||||||

| HR | 1.36 | 1.27 | 0.84 | 0.80 | 1.03 | 1.07 | 0.96 |

| 95%CI | 0.87-2.14 | 0.81-1.99 | 0.53-1.31 | 0.51-1.26 | 0.65-1.65 | 0.69-1.67 | 0.83-1.12 |

| P value | 0.008 | 0.034 | 0.061 | 0.048 | 0.889 | 0.518 | 0.634 |

| Model 11 | |||||||

| HR | 1.33 | 1.24 | 0.83 | 0.79 | 1.05 | 1.06 | 0.97 |

| 95%CI | 0.84-2.10 | 0.79-1.92 | 0.51-1.28 | 0.50-1.23 | 0.66-1.71 | 0.68-1.65 | 0.84-1.13 |

| P value | 0.012 | 0.039 | 0.066 | 0.054 | 0.851 | 0.525 | 0.619 |

| Model 22 | |||||||

| HR | 1.41 | 1.31 | 0.85 | 0.81 | 1.04 | 1.08 | 0.95 |

| 95%CI | 1.08-1.96 | 1.02-1.86 | 0.59-1.27 | 0.66-1.24 | 0.64-1.72 | 0.70-1.73 | 0.82-1.12 |

| P value | 0.016 | 0.037 | 0.436 | 0.294 | 0.841 | 0.701 | 0.593 |

Subgroup analyses were conducted to examine potential heterogeneity in the effect of electroacupuncture on emotional remission. A significantly stronger treatment effect was observed in patients with higher baseline anxiety (HADS-A ≥ 8), with an HR of 2.12 (95%CI: 1.42-3.59; P for interaction = 0.021). Similar subgroup effects were noted for patients with elevated body image disturbance (BIS ≥ 12; HR = 1.98, 95%CI: 1.31-3.17; P for interaction = 0.033) and lower perceived social support (PSSS < 60; HR = 2.03, 95%CI: 1.26-3.32; P for interaction = 0.017; Figure 4B and Table 7). No significant treatment interaction was detected in the corresponding low-risk subgroups.

| Subgroup variable | Stratum | HR1 (95%CI) | P value for interaction2 |

| Anxiety level (HADS-A baseline) | High (≥ 8) | 2.12 (1.42-3.59) | 0.021 |

| Low (< 8) | 1.24 (0.78-2.02) | ||

| Body image disturbance (BIS) | High (≥ 12) | 1.98 (1.31-3.17) | 0.033 |

| Low (< 12) | 1.15 (0.71-1.96) | ||

| Social support (PSSS) | Low (< 60) | 2.03 (1.26-3.32) | 0.017 |

| High (≥ 60) | 1.18 (0.73-1.91) |

In this controlled retrospective study of patients with moderate to severe LARS following sphincter-preserving surgery for rectal cancer, we found that electroacupuncture was associated with significant improvements across multiple psychological and functional domains. Compared with standard postoperative care, patients receiving electroacupuncture demonstrated faster emotional remission, with over half of them experiencing clinically meaningful reductions in anxiety within two weeks. This temporal advantage was corroborated by Kaplan-Meier analysis and an odds ratio of 4.7 for emotional recovery at 4 weeks. Electroacupuncture also led to substantial improvements in depressive symptoms, body-image disturbance, coping capacity, perceived social support, and overall quality of life. In parallel, LARS scores declined more rapidly, indicating a tangible recovery in bowel function. Multivariate Cox modeling identified baseline LARS severity and body-image disturbance as independent predictors of delayed emotional response, whereas subgroup analysis revealed significantly greater benefit in patients with elevated psychological burden. These findings suggest that electroacupuncture may exert a multidimensional therapeutic effect in LARS, simultaneously addressing somatic dysfunction and psychological distress in a subset of patients who are typically underserved by conventional rehabilitation approaches.

The observed emotional benefits of electroacupuncture in this cohort may be partially explained by its influence on neurobiological systems involved in affective regulation and gut-brain communication[7,8,11]. Preclinical and neuro

In addition to its emotional effects, electroacupuncture was associated with accelerated improvement in bowel function, as evidenced by significant reductions in LARS scores as early as one week after intervention[19-21]. This functional recovery is likely mediated by neuromodulation of pelvic autonomic networks, particularly through stimulation of sacral afferents and parasympathetic fibers involved in anorectal coordination[22]. Experimental studies have demonstrated that electroacupuncture at points such as BL33 and ST36 can enhance internal anal sphincter tone, improve rectal compliance, and normalize colonic motility patterns via central-peripheral reflex arcs[23]. The rationale for choosing these points is supported by both anatomical and functional data. ST36 has been shown to modulate vagal afferent activity and reduce gut inflammation in preclinical models[23], while BL33 directly stimulates the sacral plexus, which governs anorectal neuromuscular coordination. Their combined stimulation is postulated to activate bidirectional signaling along the gut-brain axis, enhancing both enteric and emotional homeostasis[24]. These mechanisms are distinct from, yet synergistic with, the psychophysiological modulation discussed previously - suggesting a dual-pathway model of action wherein electroacupuncture simultaneously targets neuromotor dysfunction and affective dysregulation[24]. Compared with other non-pharmacological interventions for LARS - such as cognitive behavioral therapy, pelvic floor biofeedback, and dietary modification - electroacupuncture offers a unique advantage by addressing both somatic and psychological symptoms through an integrated neurophysiological mechanism[25]. While cognitive behavioral therapy is effective in improving coping strategies and reducing emotional distress, it does not directly modulate gastrointestinal function. Similarly, pelvic floor training improves anorectal mechanics but exerts limited influence on mood or anxiety[26]. In contrast, electroacupuncture may deliver parallel improvements across physical and emotional domains, which is especially valuable in complex survivorship syndromes like LARS where these domains are deeply intertwined[27]. Future comparative studies are needed to benchmark electroacupuncture against these established modalities in terms of efficacy, feasibility, and patient preference. When compared to standard interventions for LARS, such as pelvic floor biofeedback, dietary regulation, and antidiarrheal agents, electroacupuncture offers the advantage of broader symptom coverage and higher integration with patient preferences, particularly in settings where pharmacologic management is limited by intolerance or side effects[28]. Moreover, the linkage between emotional relief and functional improvement observed in our study underscores the clinical relevance of addressing both dimensions concurrently. In this respect, electroacupuncture represents a rare example of a single modality with bidirectional benefit across the somatic and psychological domains - a critical feature in the multidisciplinary management of complex survivorship syndromes such as LARS.

The differential treatment responses observed across psychological subgroups in our cohort provide important insights into the heterogeneity of intervention efficacy and highlight the need for stratified rehabilitation strategies in LARS management. Patients with elevated baseline anxiety, pronounced body image disturbance, or lower levels of perceived social support experienced significantly greater benefit from electroacupuncture in terms of emotional remission. These findings align with prior work in psycho-oncology demonstrating that individuals with higher affective vulnerability or lower resilience may exhibit amplified sensitivity to supportive interventions, possibly due to heightened neuroplasticity or greater symptom salience[29]. From a clinical standpoint, this suggests that early psychological profiling - using instruments such as HADS, BIS, and PSSS - may help identify patients who are most likely to respond to integrative therapies such as electroacupuncture. Incorporating such assessments into routine postoperative care could enable a more tailored allocation of limited resources, aligning with the broader movement toward precision psychosocial oncology[9,28]. Furthermore, the linkage between emotional dysregulation and delayed functional recovery seen in our regression models underscores the role of psychological status not merely as a comorbidity, but as a potential mediator of somatic outcomes[30]. Future trials should explore adaptive intervention models wherein psychosocial metrics dynamically inform the intensity and modality of supportive care, including combinations of electroacupuncture, behavioral therapy, and resilience-enhancing programs[4].

Taken together, our findings support the use of electroacupuncture as a multidimensional rehabilitation strategy that concurrently addresses emotional distress and bowel dysfunction in patients with LARS. This study contributes to a growing body of evidence advocating for integrative, patient-centered approaches in colorectal cancer survivorship care[31]. Strengths of the study include the use of validated, multidomain outcome measures; a clearly defined clinical cohort with moderate to severe symptoms, and rigorous modeling of time-to-response and psychological moderators[13]. Moreover, the demonstration of early emotional benefit and subgroup-specific responsiveness provides a compelling rationale for incorporating psychological profiling into postoperative care pathways.

However, several limitations merit consideration. The retrospective and non-randomized design introduces potential selection bias and limits causal inference. Although efforts were made to adjust for major covariates in multivariate analyses, the lack of propensity score matching or sensitivity analysis limits the robustness of confounder control. These unmeasured confounders may have influenced both group assignment and outcomes. Future studies incorporating these statistical techniques would offer stronger internal validity. The relatively short follow-up period precludes assessment of long-term sustainability of effects. While early symptom relief was evident within the 4-week intervention window, the durability of these benefits remains uncertain. Prior studies in acupuncture and mind-body interventions suggest that maintenance effects may vary based on psychological resilience, reinforcement frequency, and neuroplastic adaptation. It is possible that without continued stimulation or adjunctive behavioral support, therapeutic gains may diminish over time. Longitudinal studies with extended follow-up periods are needed to map symptom trajectories, identify early relapses, and determine whether booster sessions or integrated care models can sustain improvements in both bowel function and emotional health. Another notable limitation is the absence of blinding and the potential influence of patient expectations on treatment response. Given the cultural familiarity and widespread acceptance of acupuncture in China, participants in the electroacupuncture group may have held more positive beliefs or prior experience, which could enhance placebo effects and subjective improvements. While such expectancy-related mechanisms are an inherent component of integrative therapies, their contribution to the observed outcomes cannot be fully disentangled in the current design. Future studies may consider measuring and adjusting for baseline treatment expectations to clarify specific vs non-specific treatment effects. Additionally, cultural familiarity with acupuncture among Chinese patients may influence generalizability to other settings. Future research should focus on prospective randomized controlled trials with longer follow-up, mechanistic endpoints, and cross-cultural validation. Incorporating neurophysiological measures, such as vagal tone or functional neuroimaging, may further elucidate the pathways linking electroacupuncture to psychological and functional outcomes. Ultimately, a precision-based model integrating psychometric screening with stratified intervention delivery may optimize benefit for the growing population of rectal cancer survivors living with LARS. Given the lack of multiple testing correction in subgroup analyses, the potential for false-positive findings exists. Future studies should incorporate statistical adjustments to confirm the observed effect modification across psychological strata.

This study provides evidence that electroacupuncture offers meaningful benefits for both emotional and functional recovery in patients with LARS following rectal cancer surgery. By demonstrating accelerated emotional remission, improved bowel function, and enhanced quality of life - particularly in psychologically vulnerable subgroups - this research highlights the therapeutic value of integrating neuropsychological and somatic rehabilitation. Given its favorable safety profile, cultural acceptability, and multidimensional impact, electroacupuncture may serve as a viable adjunct in the personalized management of LARS. Further prospective trials are warranted to confirm these findings, explore underlying mechanisms, and inform precision-based supportive care strategies.

The authors would like to thank Wen-Tao Li for his assistance with the statistical analyses and Mei Zhang for her valuable input during patient follow-up coordination. We also acknowledge the clinical staff at Guang’anmen Hospital and Peking University Lu’an Hospital for their support in data collection. Their contributions were essential to the successful completion of this study.

| 1. | Kim H, Kim H, Cho OH. Bowel dysfunction and lower urinary tract symptoms on quality of life after sphincter-preserving surgery for rectal cancer: A cross-sectional study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2024;69:102524. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Emmertsen KJ. Low Anterior Resection Syndrome. In: Baatrup G, editor. Multidisciplinary Treatment of Colorectal Cancer. Cham: Springer, 2021: 133-139. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Sakr A, Sauri F, Alessa M, Zakarnah E, Alawfi H, Torky R, Kim HS, Yang SY, Kim NK. Assessment and management of low anterior resection syndrome after sphincter preserving surgery for rectal cancer. Chin Med J (Engl). 2020;133:1824-1833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Xu LL, Cheng TC, Xiang NJ, Chen P, Jiang ZW, Liu XX. Risk factors for severe low anterior resection syndrome in patients with rectal cancer undergoing sphincterpreserving resection: A systematic review and metaanalysis. Oncol Lett. 2024;27:30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Pape E, Burch J, van Ramshorst G, Van Nieuwenhove Y, Taylor C. CN63 Intervention pathways for low anterior resection syndrome after sphincter-saving rectal cancer surgery: A systematic scoping review. Ann Oncol. 2022;33:S1372. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Koifman E, Armoni M, Gorelik Y, Harbi A, Streltsin Y, Duek SD, Brun R, Mazor Y. Long term persistence and risk factors for anorectal symptoms following low anterior resection for rectal cancer. BMC Gastroenterol. 2024;24:31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chen Y, Shen P, Li Q, Ong SS, Qian Y, Lu H, Li M, Xu T. Electroacupuncture and Tongbian decoction ameliorate CUMS-induced depression and constipation in mice via TPH2/5-HT pathway of the gut-brain axis. Brain Res Bull. 2025;221:111207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhang Q, Deng P, Chen S, Xu H, Zhang Y, Chen H, Zhang J, Sun H. Electroacupuncture and human iPSC-derived small extracellular vesicles regulate the gut microbiota in ischemic stroke via the brain-gut axis. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1107559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tang L, Zhang X, Zhang B, Chen T, Du Z, Song W, Chen W, Wang C. Electroacupuncture remodels gut microbiota and metabolites in mice with perioperative neurocognitive impairment. Exp Gerontol. 2024;194:112507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Feng P, Wu Z, Liu H, Shen Y, Yao X, Li X, Shen Z. Electroacupuncture Improved Chronic Cerebral Hypoperfusion-Induced Anxiety-Like Behavior and Memory Impairments in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats by Downregulating the ACE/Ang II/AT1R Axis and Upregulating the ACE2/Ang-(1-7)/MasR Axis. Neural Plast. 2020;2020:9076042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tian MY, Yang YD, Qin WT, Liu BN, Mou FF, Zhu J, Guo HD, Shao SJ. Electroacupuncture Promotes Nerve Regeneration and Functional Recovery Through Regulating lncRNA GAS5 Targeting miR-21 After Sciatic Nerve Injury. Mol Neurobiol. 2024;61:935-949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wu F, Zhu J, Wan Y, Subinuer Kurexi, Zhou J, Wang K, Chen T. Electroacupuncture Ameliorates Hypothalamic‒Pituitary‒Adrenal Axis Dysfunction Induced by Surgical Trauma in Mice Through the Hypothalamic Oxytocin System. Neurochem Res. 2023;48:3391-3401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wang X, Wang J, Han R, Yu C, Shen F. Neural circuit mechanisms of acupuncture effect: where are we now? Front Neurol. 2024;15:1399925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bishop FL, Lewith GT. Patients' preconceptions of acupuncture: a qualitative study exploring the decisions patients make when seeking acupuncture. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2013;13:102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ching SSY, Mok ESB. Adoption of healthy lifestyles among Chinese cancer survivors during the first five years after completion of treatment. Ethn Health. 2022;27:137-156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Leyro TM, Zvolensky MJ, Bernstein A. Distress tolerance and psychopathological symptoms and disorders: a review of the empirical literature among adults. Psychol Bull. 2010;136:576-600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 645] [Cited by in RCA: 564] [Article Influence: 35.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Huizinga JD, Liu L, Barbier A, Chen JH. Distal Colon Motor Coordination: The Role of the Coloanal Reflex and the Rectoanal Inhibitory Reflex in Sampling, Flatulence, and Defecation. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:720558. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wang X, Chen JD. Therapeutic potential and mechanisms of sacral nerve stimulation for gastrointestinal diseases. J Transl Int Med. 2023;11:115-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Rodrigues JM, Ventura C, Abreu M, Santos C, Monte J, Machado JP, Santos RV. Electro-Acupuncture Effects Measured by Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging-A Systematic Review of Randomized Clinical Trials. Healthcare (Basel). 2023;12:2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wood A, Glynn TK, Cahalin LP. The Rehabilitation of Individuals With Gastrointestinal Issues Beyond Pelvic Floor Muscle Function: Considering a Larger Picture for Best Practice. J Womens Health Phys Therap. 2022;46:167-174. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 21. | Borsati A, Toniolo L, Trestini I, Tregnago D, Belluomini L, Fiorio E, Lanza M, Schena F, Pilotto S, Milella M, Avancini A. Feasibility of a novel exercise program for patients with breast cancer offering different modalities and based on patient preference. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2024;70:102554. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Keefer L, Bedell A, Norton C, Hart AL. How Should Pain, Fatigue, and Emotional Wellness Be Incorporated Into Treatment Goals for Optimal Management of Inflammatory Bowel Disease? Gastroenterology. 2022;162:1439-1451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cortiana V, Abbas RH, Nadar S, Mahendru D, Gambill J, Menon GP, Park CH, Leyfman Y. Reviewing the Landscape of Cancer Survivorship: Insights from Dr. Lidia Schapira's Programs and Beyond. Cancers (Basel). 2024;16:1216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wang T, Wu N, Wang S, Liu Y. The relationship between psychological resilience, perceived social support, acceptance of illness and mindfulness in patients with hepatolenticular degeneration. Sci Rep. 2025;15:1622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Jaffal SM. Neuroplasticity in chronic pain: insights into diagnosis and treatment. Korean J Pain. 2025;38:89-102. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Cho KJ, Lee NS, Lee YS, Jeong WJ, Suh HJ, Kim JC, Koh JS. The Changes of Psychometric Profiles after Medical Treatment of Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Suggestive of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2015;13:269-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Yeung SC, Irwin MG, Cheung CW. Environmental Enrichment in Postoperative Pain and Surgical Care: Potential Synergism With the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Pathway. Ann Surg. 2021;273:86-95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 28. | Hermans EJ, Hendler T, Kalisch R. Building Resilience: The Stress Response as a Driving Force for Neuroplasticity and Adaptation. Biol Psychiatry. 2025;97:330-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Zhao QY, Luo JC, Su Y, Zhang YJ, Tu GW, Luo Z. Propensity score matching with R: conventional methods and new features. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9:812. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 29.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Yang X, Wang T, Jiang Y, Ren F, Jiang H. Patients' Expectancies to Acupuncture: A Systematic Review. J Integr Complement Med. 2022;28:202-217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Han X, Gao Y, Yin X, Zhang Z, Lao L, Chen Q, Xu S. The mechanism of electroacupuncture for depression on basic research: a systematic review. Chin Med. 2021;16:10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |