Published online Jan 19, 2026. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v16.i1.109365

Revised: June 17, 2025

Accepted: October 14, 2025

Published online: January 19, 2026

Processing time: 237 Days and 0.2 Hours

Drug utilization research has an important role in assisting the healthcare adm

To evaluate patterns of utilization of antipsychotic drugs and direct medical cost analysis in patients newly diagnosed with schizophrenia.

The present study was observational in type and based on a retrospective cohort to evaluate patterns of utilization of antipsychotic drugs using World Health Organization (WHO) core prescribing indicators and anatomical therapeutic chemical/defined daily dose indicators. We also calculated direct medical costs for a period of 6 months.

This study has found that atypical antipsychotics are the mainstay of treatment for schizophrenia in every age group and subcategories of schizophrenia. The evaluation based on WHO prescribing indicators showed a low average number of drugs per prescription and low prescribing frequency of antipsychotics from the National List of Essential Medicines 2015 and the WHO Essential Medicines List 2019. The total mean drug cost of our study was 1396 Indian rupees. The total mean cost due to the investigation in our study was 1017.34 Indian rupees. The

The information from the present study can be used for reviewing and updating treatment policy at the institutional level.

Core Tip: This study found that atypical antipsychotics had the highest prescribing frequency among antipsychotics in all schizophrenia categories. Olanzapine was the most frequently prescribed atypical antipsychotic. Half of the patients received concomitant drugs due to the presence of psychiatric and non-psychiatric comorbidities. Trihexyphenidyl had the highest prescribing frequency among concomitant drugs. There was a low average number of drugs per prescription, low prescribing frequency of antipsychotics, and low prescribing frequency of injectable formulations of antipsychotics. The present study provided useful data to review and update treatment policy.

- Citation: Haider A, Saha L, Basu D. Patterns of utilization of antipsychotic drugs and direct medical costs among patients with schizophrenia in a tertiary care hospital. World J Psychiatry 2026; 16(1): 109365

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v16/i1/109365.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v16.i1.109365

Schizophrenia has a substantial global societal burden and ranks 11th among causes of years lived with disability, both in terms of human and financial cost[1]. It is estimated to affect 0.4% to 1.4% of the population, a prevalence approaching about 1%[2]. The direct medical expenses of treating schizophrenia range from 1.4% to 3.0% of the total national health costs according to an evaluation of cost of illness/cost of treatment studies for the disorder conducted worldwide[3]. The cost of care for schizophrenia disorder in India has seen a two-fold increase in the previous decade[4]. Being a disease of a disabling nature, it carries a predominant risk of unemployment, contributing to major expenditures in terms of indirect medical costs.

Antipsychotic drugs are the centerpieces for the treatment of schizophrenia. Prevention of relapse and a decrease in the severity of additional acute episodes over time are the cardinal aims of the management of patients with schizophrenia with antipsychotic drugs. Variations have been observed in prescribing patterns of two generations of antipsychotics across different parts of the world, chiefly concerning the medications favored within each category[5,6]. Variations are also attributed to several other factors, such as adverse drug reactions with therapy, patients’ characteristics, concomitant diseases, and costs[5-8]. Although treatment guideline recommendations include atypical antipsychotics as first-line therapy, cost is the prime factor affecting prescribing trends of these drugs in both developed and developing nations[4,8,9].

To the best of our knowledge, no single study has assessed prescribing patterns of antipsychotics with a direct medical cost analysis in this illness for a 6-month follow-up period in a tertiary care hospital. Hence, this study aimed to observe the drug utilization patterns of antipsychotic drugs along with direct medical cost analysis in newly diagnosed cases of schizophrenia with a 6-month follow-up from medical records of the patients in a tertiary care hospital of northern India.

The present study was observational in type and based on a retrospective cohort to evaluate patterns of utilization of antipsychotic drugs using World Health Organization (WHO) core prescribing indicators and anatomical therapeutic chemical (ATC)/defined daily dose (DDD) indicators. We also calculated direct medical costs in newly diagnosed cases of schizophrenia for 6 months. Since it was a retrospective cohort study from retrieved case files from medical records, we were only able to assess direct medical costs, i.e. costs associated with providing treatment. The Institutional Ethics Committee approved the study [No. INT/IEC/2021/SPL-1090 dated 14/07/2021, data (case records)].

Cases of the schizophrenia (diagnosed based on standard diagnostic criteria) that were registered as outpatients in the Department of Psychiatry, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER), Chandigarh between January 1, 2016 and December 31, 2018 were retrieved from the medical records section within the Department of Psychiatry, PGIMER Chandigarh. Data (case records) of these cases were screened for newly diagnosed schizophrenia, which was defined as a history of illness/symptomatology not more than 2 years. Then, newly diagnosed treatment-naïve schizophrenia cases were screened further for eligibility for the study per the defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Complete data of eligible cases related to “demographic details, indicators of drug utilization research, and parameters related to direct medical cost analysis” were noted in Case Record Forms from all Out Patient Department (OPD) prescriptions and in-hospital admissions files for 6 months.

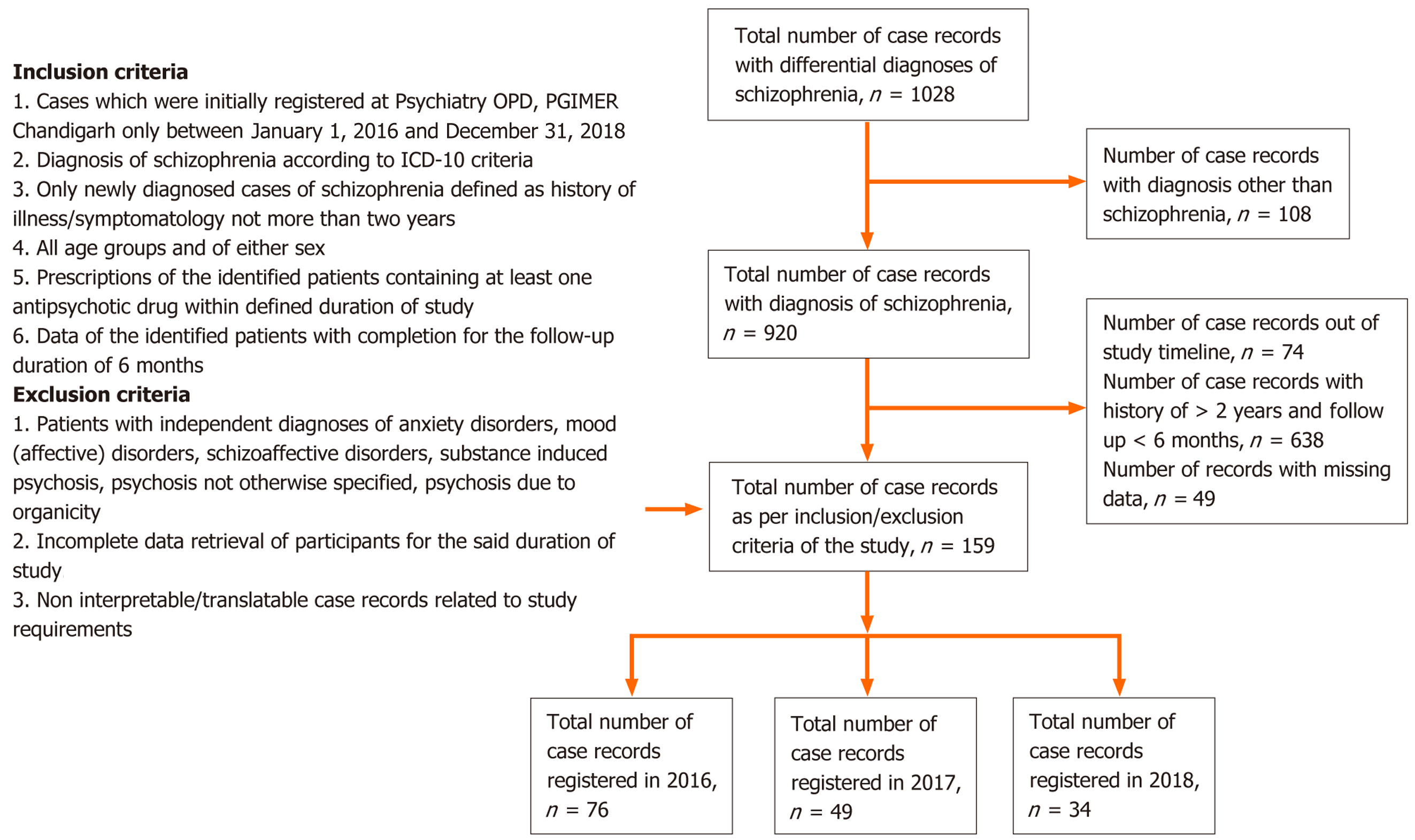

Inclusion criteria were: (1) Cases that were initially registered at the Psychiatry OPD, PGIMER, Chandigarh between January 1, 2016 and December 31, 2018; (2) Diagnosis of schizophrenia according to the International Classification of Diseases-10 criteria; (3) Only newly diagnosed cases of schizophrenia defined as a history of illness/symptomatology not more than 2 years; (4) All age groups and of either sex; (5) Prescriptions of the identified patients containing at least one antipsychotic drug within the defined duration of study; and (6) Data of the identified patients with completion for the follow-up duration of 6 months.

Exclusion criteria were: (1) Patients with independent diagnoses of anxiety disorders, mood (affective) disorders, schi

Prescribing patterns of antipsychotic drugs were evaluated for each case using the Drug Utilizing Research WHO core drug prescribing indicators and ATC/DDD methodological indicators.

WHO core drug prescribing indicators[10,11]: (1) Average number of drugs per visit (quantifies the degree of poly

ATC/DDD methodological indicators[12]: (1) DDD per 1000 inhabitants per day (DID) for antipsychotics; (2) Prescribed daily dose (PDD) of the antipsychotics; and (3) PDD-to-DDD ratio.

Direct medical costs for management of newly diagnosed schizophrenia were evaluated as follows: (1) Average drug costs in the 6-month follow-up period; (2) Average cost of antipsychotic drugs in the months of the follow-up period; (3) Percentage of drug cost spent on injections in the 6-month follow-up period; and (4) Average of the total direct medical costs encompassing drug costs, diagnostic and therapeutic investigations, OPD visits, and in-hospital admissions costs in the 6-month follow-up period.

The monthly index of medical specialties and current index of medical specialties, India’s latest version, were referred for cost standardization for calculating the cost of a drug. The rates for different brands of a particular drug were acquired from the current index of medical specialties and monthly index of medical specialties India. The average rates for a particular drug was then computed and utilized for the cost of care analysis in this study. The ten most frequently prescribed brands for each drug were considered for their average dose and cost relationship. These data were used to calculate the per mg cost of the drug. The per mg cost calculation of olanzapine is demonstrated as an example in Table 1. A similar approach was utilized for other categories of drugs as well, and similarly the per mg cost of various drugs, which were prescribed in this study population, was calculated. This per mg cost was multiplied by the daily dose consumed by the patient to get the cost spent by the patient on that drug per day. Further costs spent by the patient for a particular drug were calculated as follows: Cost for a particular drug = daily dose consumed by patient × duration for that particular drug therapy × per mg cost for that particular drug. Cost encompassing OPD visits and diagnostic and therapeutic investigations were computed from the price list of PGIMER, Chandigarh. It is available on the hospital’s official website (https://pgimer.edu.in/PGIMER_PORTAL/PGIMERPORTAL/home.jsp). Cost encompassing in-hospital admissions was measured from the final bill at the time of discharge from the hospital in every inpatient case file.

| Drug brands (generic name) | Tablets (number) in one strip/package with dose (mg) of each tablet | Cost (Indian rupees) of one strip/package |

| Tolaz MD 10 (olanzapine) | 10 tablets, 10 mg each | 29 |

| Oleanz 10 (olanzapine) | 10 tablets, 10 mg each | 86 |

| Olan 10 (olanzapine) | 10 tablets, 10 mg each | 65 |

| Olanz 10 (olanzapine) | 10 tablets, 10 mg each | 48 |

| Olimelt 10 (olanzapine) | 10 tablets, 10 mg each | 78 |

| Dopin 10 (olanzapine) | 10 tablets, 10 mg each | 62 |

| Jolyon 10 (olanzapine) | 10 tablets, 10 mg each | 55 |

| Lanopin 10 (olanzapine) | 10 tablets, 10 mg each | 61 |

| Olandus 10 (olanzapine) | 10 tablets, 10 mg each | 51 |

| Olexar 10 (olanzapine) | 10 tablets, 10 mg each | 47 |

Statistical analysis was done using SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, United States. Continuous data has been stated as mean ± SD. The categorical data was expressed as frequency and relative frequency. Various parameters related to drug utilization patterns and cost were compared between 2016, 2017, and 2018 registered cases with the help of the analysis of variance test. In cases of statistical significance, a post hoc Tukey (honestly significant difference) (least square difference) was done to find out the presence of a difference between the two groups.

A total of 1028 case records registered in 2016, 2017, and 2018 with differential diagnoses of schizophrenia were screened. This included the patients who were suspected of schizophrenia on their initial visits. Out of 1028 case records, 108 did not have the final diagnosis of schizophrenia. In the remaining 920 case records with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, 712 case records did not meet the inclusion/exclusion criteria. A total of 159 patient files were included in the final analysis with n = 76 in 2016, n = 49 in 2017, and n = 34 in 2018 as depicted in Figure 1. The baseline sociodemographic characteristics of the study population are represented in Table 2.

| Age (years) | Number of patients (n = 159) | Percentage (%) |

| < 18 | 14 | 8.8 |

| 18-30 | 98 | 61.6 |

| 31-40 | 29 | 18.2 |

| > 40 | 18 | 11.3 |

| Gender distribution of study population | ||

| Age (years) | mean | SD |

| Age (n = 159) | 27.74 | 9.76 |

| Age for men (n = 90) | 26.74 | 9.04 |

| Age for women (n = 69) | 29.04 | 10.55 |

| Frequency of comorbidities | ||

| Comorbidity | Frequency (n = 92) | Relative frequency (%) |

| F17 (nicotine dependence) | 23 | 0.25 |

| F12.2 (cannabis dependence) | 9 | 0.10 |

| F10.2 (alcohol dependence) | 5 | 0.05 |

| E66.9 (obesity) | 10 | 0.11 |

| Other psychiatric comorbidities | 33 | 0.36 |

| Other non-psychiatric comorbidities | 12 | 0.13 |

The mean duration of history of illness (schizophrenia) in 159 patients was 14.32 ± 8.06 months. Among 159 patients, five subcategories of schizophrenia were seen. The most common among them was F20.0 (paranoid schizophrenia) with a relative frequency of 69.2%. The other subcategories were F20.3 (undifferentiated schizophrenia), F20.6 (simple schizophrenia), F20.1 (hebephrenic schizophrenia), and F20.2 (catatonic schizophrenia) with relative frequencies of 25.8%, 3.8%, 0.6%, 0.6% respectively.

Among 159 patients, 55 patients had comorbidities, including both psychiatric and non-psychiatric illnesses. Among psychiatric comorbid conditions, the most common were F17 (nicotine dependence), F12.2 (cannabis dependence), and F10.2 (alcohol dependence). F17 (nicotine dependence) was present in 23 patients and amounted to 41.18% of all the comorbidities. Among non-psychiatric comorbid conditions, E66.9 (obesity) accounted for the highest number. Other comorbidities included F45 (somatization disorder), F60 (specific personality disorders), Z63 (problems in relationship with partner), F42 (obsessive compulsive disorder), G40 (epilepsy), E88.81 (metabolic disorders), I10 (essential hypertension), etc. The frequency of these comorbid conditions is represented in Tables 2 and 3. Substance abuse was seen in 43 out of 159 patients depicted in Tables 2 and 3. The history was collected for abused substances, which included alcohol, tobacco, and cannabis. Six patients abused all the above substances. Nine patients co-abused both tobacco and cannabis, and 6 patients co-abused both tobacco and alcohol. Mean weight (kg), height (cm), waist circumference (cm), and body mass index of the study population were 63.45 ± 16.24, 163.47 ± 11.59, 84.16 ± 13.42, and 23.67 ± 5.51, res

| History of illness (in months) | Number of patients (n = 159) | Mean years of history of illness for subcategories | SD |

| < 6 months | 40 | 3.49 | 1.77 |

| 6-12 months | 42 | 11.05 | 1.71 |

| 13-24 months | 77 | 21.74 | 2.93 |

| 0-24 months | 159 | 14.32 | 8.06 |

| Substance abuse in study population | |||

| Characteristic | Alcohol use | Tobacco use | Cannabis use |

| Yes (present) | 20 | 35 | 15 |

| No (absent) | 139 | 124 | 144 |

| Total | 159 | 159 | 159 |

A total of 908 prescriptions from 159 patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia with 6 months of follow-up were recorded. The average number of prescriptions per patient registered in 2016, 2017, and 2018 was 5.84, 5.63, and 5.68, respectively. The average number of prescriptions per patient for 159 patients was 5.63. A total of 1819 drug products were prescribed in 908 prescriptions in 3 years, of which antipsychotics were prescribed 952 times (52.34%). Each prescription (n = 908) contained ≥ 1 antipsychotic drug (1.03). The percentage of antipsychotics prescribed by generic names was 78.84%. Over half (59.70%) of the prescriptions had concomitant medications, and 26.86% prescribed antipsychotics were from the National List of Essential Medicines (NLEM) 2015 and the WHO Essential Medicines List (EML) 2019. Prescription for injections of antipsychotics was 3.19%. Only two antipsychotics in injectable formulations were prescribed, i.e. injection fluphenazine decanoate and olanzapine. The percentage of antibiotics was zero in 908 prescriptions. The percentage of fixed-drug combinations (FDC) was 2.86%. Seven prescriptions had FDC of anti

The average number of drugs per prescription was 1.94 ± 0.99 among 908 prescriptions. The percentage of concomitant drugs prescribed by generic names was 48.19%. The percentage of prescriptions containing all injections was 3.19. The majority (89.89%) of prescribed antipsychotics were from the NLEM 2015 and 19.77% from the WHO EML 2019. A statis

Olanzapine was prescribed the maximum number of times (85 times) as the first prescribed antipsychotic drug for a patient, followed by risperidone (42 times), aripiprazole (18 times), amisulpride (8 times), and fluphenazine/trifluoperazine/quetiapine (2 times for these three drugs). Switching from one antipsychotic to another antipsychotic in the 6-month follow-up period was seen 24 times (twice in 1 patient, once in 22 patients). Olanzapine had the highest switching frequency (10 times) to another antipsychotic drug, followed by aripiprazole (5 times). The most common switching was from olanzapine to aripiprazole (6 times).

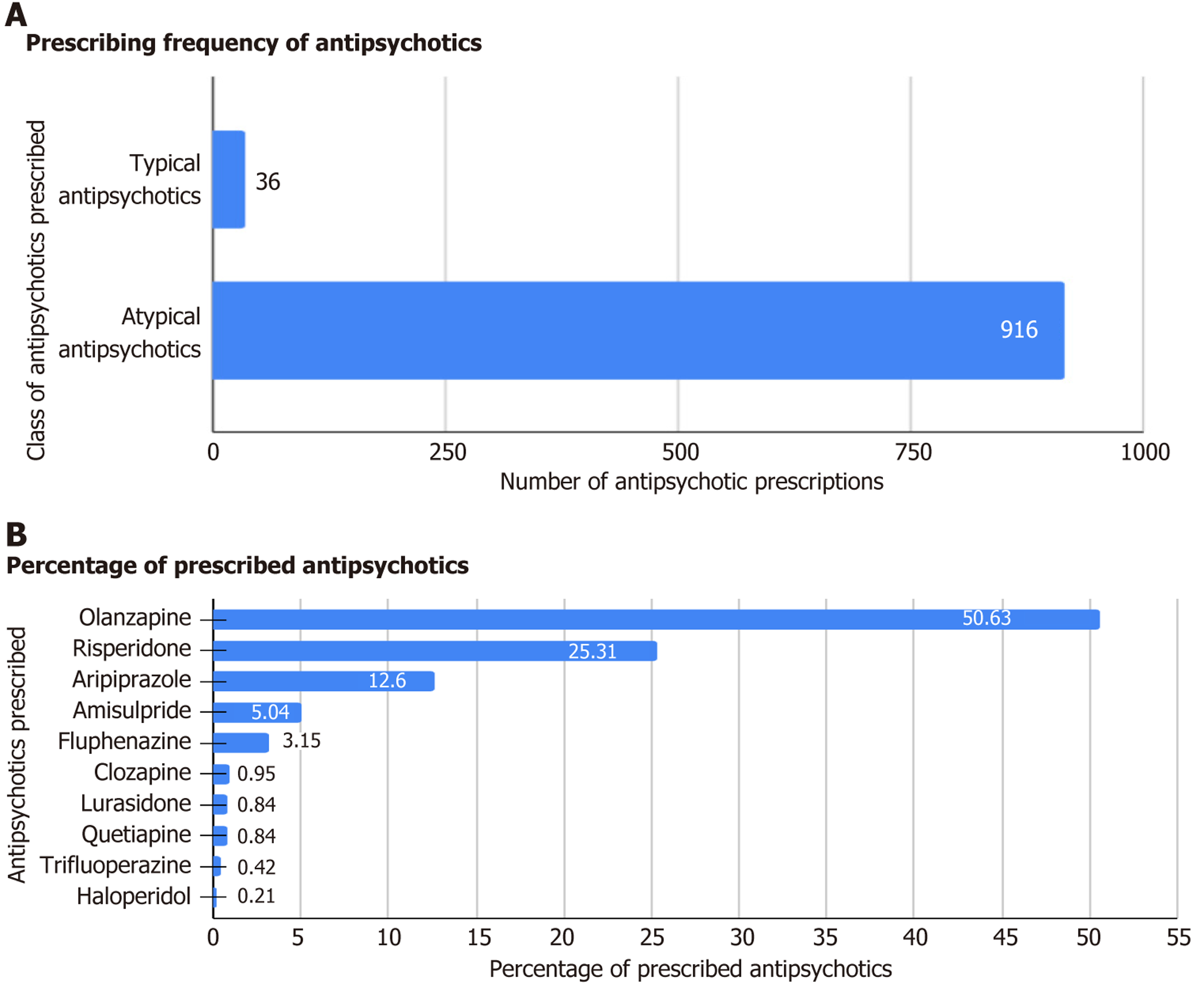

Out of 908 prescriptions antipsychotics were prescribed 952 times. Among the antipsychotics prescribed, typical antipsychotics were prescribed 36 times (37.80%), and atypical antipsychotics were prescribed 916 times (96.20%). The highest prescribing frequency was for olanzapine (482), followed by risperidone (241), aripiprazole (120), amisulpride (48), and fluphenazine (30) as depicted in Figure 2. Prescribing frequencies for clozapine, lurasidone, quetiapine, trifluoperazine, and haloperidol were less than 10. Among typical antipsychotics, fluphenazine had the highest prescribing frequency. A total of 1819 drug products were prescribed in 908 prescriptions of which 867 (47.61%) were concomitant drugs. Among concomitant drugs the highest prescribing frequency was for trihexyphenidyl (298), sedative-hypnotics (252), antidepressants (199), propranolol (42), and antiepileptics (18). Benzodiazepines had the highest frequency (251) among sedative-hypnotics with the most common prescribing of clonazepam. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors had the highest frequency (166) among antidepressants with fluoxetine the most commonly prescribed.

The WHO ATC/DDD methodological indicators, including DID, PDD, and PDD/DDD ratio for antipsychotics, were calculated as depicted in Table 4. Among typical antipsychotics, the PDD for fluphenazine was 1.4 times more than its daily than its daily defined dose.

| Drug | ATC code | DDD (mg) | DID (mg) | PDD (mg) | PDD/DDD |

| Fluphenazine | N05AB02 | 1 | 0.0794 | 1.40 | 1.400 |

| Trifluoperazine | N05AB06 | 20 | 0.0030 | 7.59 | 0.380 |

| Haloperidol | N05AD01 | 8 | 0 | 4.50 | 0.560 |

| Olanzapine | N05AH03 | 10 | 1.5600 | 14.36 | 1.436 |

| Risperidone | N05AX08 | 5 | 0.3745 | 3.55 | 0.710 |

| Aripiprazole | N05AX12 | 15 | 0.2237 | 11.56 | 0.770 |

| Amisulpride | N05AL05 | 400 | 0.0755 | 212.95 | 0.530 |

| Quetiapine | N05AH04 | 400 | 0.0062 | 78.53 | 0.190 |

| Lurasidone | N05AE05 | 60 | 0.0184 | 48.17 | 0.800 |

| Clozapine | N05AH02 | 300 | 0.0066 | 185.38 | 0.620 |

The average drug cost in the 6-month follow-up period for 159 patients was 3350.02 ± 5257.89 Indian rupees. The average cost of antipsychotic drugs in the 6-month follow-up period for 159 patients was 1945.25 ± 2111.71 Indian rupees as depicted in Table 5. The percentage of drug cost spent on injections was 6.07%. The average total direct medical cost (including drug cost, diagnostics and therapeutic investigations, OPD visits, and in-hospital admissions) was 4337.28 ± 5400.07 Indian rupees.

| Cost (Indian rupees) | 2016 (n = 79) | 2017 (n = 49) | 2018 (n = 34) | Total | P value |

| Cost for typical antipsychotics | 360.00 ± 158.75 | 219.67 ± 113.09 | 74.00 ± 00.00 | 259.00 ± 155.69 | 0.273 |

| Cost for atypical antipsychotics | 2820.62 ± 5983.78 | 1857.50 ± 1850.72 | 1970.88 ± 1198.21 | 2320.79 ± 4221.25 | 0.395 |

| Cost for antipsychotics | 1985.77 ± 2591.01 | 1870.18 ± 1844.14 | 1973.06 ± 1197.55 | 1945.25 ± 2111.71 | 0.953 |

| Cost for concomitant drugs | 845.17 ± 928.98 | 2220.23 ± 6117.17 | 1401.98 ± 1308.57 | 1396.23 ± 3680.37 | 0.188 |

| Total cost for drugs | 3483.21 ± 5947.95 | 3578.04 ± 5805.69 | 2715.28 ± 1595.96 | 3350.01 ± 5257.89 | 0.729 |

| Total cost for investigations | 991.28 ± 1290.30 | 924.55 ± 920.49 | 1193.18 ± 1394.26 | 1017.34 ± 1211.16 | 0.614 |

| Total direct medical cost | 4389345 ± 6062.51 | 4560.83 ± 5910.86 | 3883.37 ± 2266.12 | 4337.28 ± 5400.07 | 0.847 |

This study found that 70% of patients were less than 40 years old, whereas only 11.3% were over 40 years old. According to the current study, schizophrenia has an early onset and affects males in their early twenties and females in their late twenties and early thirties. Similar findings were observed in a study conducted by Rode et al[13], and Math et al[14]. Antipsychotic prescription patterns studies that have been conducted recently have shown that atypical antipsychotics are more frequently prescribed than typical antipsychotics because they can cause fewer extrapyramidal side effects and better manage symptoms. The present study confirmed this as atypical antipsychotics were prescribed more often than typical.

All of the parameters evaluated had demographic data that were consistent with other published study results. However, the drug utilization study in Dubai had 9.7% of patients’ ages missing and gender missing in 12%[15]. Serious medication errors can occur if demographic indicators are absent, such as dispensing medication to the wrong patients. Mentioning age facilitates the selection of the correct dose to be dispensed to any patient. The number of prescriptions in which the diagnosis was mentioned was 100%, which was higher than the other study results by Jain et al[16] (64.66%). The diagnosis should be mentioned as it facilitates the pharmacist in dispensing the correct medication, thereby reducing medication errors and the adverse consequences of dispensing wrong medication.

The current study’s prescription auditing results revealed that 908 prescriptions comprised a total of 1819 drug pro

Currently, FDCs are another significant type of medication that is prescribed. FDCs make up a very small percentage of the prescribed antipsychotic medications in our study (0.77%), similarly to the 22.5% found by Goel et al[20].

In the present study the average number of drugs per prescription was 1.94, which was slightly higher compared with the standard WHO-recommended value of 1.6-1.8[21]. This finding was less than the findings of Hazra et al[22] in which it was 3.2 and Wang et al[23] in which it was 3.54. The average number of drugs per prescription was also less than the findings of other studies conducted in India, such as Rehan et al[24] in which it was 2.4.

In the present study antipsychotics prescribed by generic names were only 78.84%, which is low compared with the standard WHO ideal value of 100%. It was more than findings from the study by Chandelkar and Rataboli[25] in which it was less than 1% and from the study done by Rehan et al[24] in which it was 1.5%. It was comparable to the findings of other studies done by Hazra et al[22] and some other international studies[26,27].

In the present study the percentage of prescriptions with injections was 3.19%, which was less than the standard range of the WHO ideal value (13.4%-24.1%). Of the injections the most commonly prescribed was that of fluphenazine decanoate. It was less than the findings from the study done by Tripathy et al[28] in which it was 8% and very low com

The percentage of antipsychotic drugs prescribed from the NLEM 2015 in our study was 26.86%, which was lower when compared with the ideal standard value of 100%. This finding was less than the findings from studies of other parts of India such as Hazra et al[22] in which it was 47.1%. India has a lower percentage of drugs prescribed from the essential drug list compared with other countries, such as South Ethiopia where it was 99.5%[27].

While adherence to essential medicines lists is ideal, certain non-listed drugs may be justified if supported by robust evidence demonstrating superior efficacy, safety, or patient outcomes in specific clinical contexts. Therefore, the hospital should encourage conducting or reviewing outcome-based research comparing EML and non-EML antipsychotics. This evidence can inform rational decisions, ensuring that any deviations from the EML are evidence-based and patient-centered.

In India the utilization of antipsychotic medications generally shows a preference for atypical antipsychotics over typical ones with olanzapine and risperidone being the most commonly prescribed. Studies indicate that a significant portion of patients receive monotherapy, but polypharmacy (multiple antipsychotics) is also observed in a notable percentage of cases.

One study found that olanzapine was prescribed in 51% of patients, followed by risperidone (23%) and quetiapine (13%)[29]. Another study indicated that 89% of patients received atypical antipsychotics with olanzapine and risperidone being the most frequently prescribed[30]. A survey of psychiatrists revealed that risperidone, olanzapine, and haloperidol were the three most commonly prescribed antipsychotics[31]. A study on patients with schizophrenia in a tertiary care hospital showed that olanzapine was the most commonly used antipsychotic, followed by risperidone and haloperidol[19]. These findings highlight the evolving landscape of antipsychotic use in India with a clear shift towards atypical agents and a continued need for careful consideration of individual patient needs and potential side effects.

For people with schizophrenia a relapse or worsening of psychosis frequently results in psychiatric-related hospitalization. The current study found that patients who were started on atypical drugs had a lower rate of hospitalizations (in line with some earlier research). Concomitant medicines were commonly used in the current study. Similar to the findings from Nielsen et al[32], nearly 60% of patients got some form of concurrent medication related to psychiatry.

The total DID of antipsychotic use showed high consumption of antipsychotics in the population. This is similar to the findings of a 10-year database-based study conducted in the United States[33] and in contrast to the findings of an Indian study conducted by Lahon et al[34] in which the antipsychotic consumption was quite low. For trifluoperazine, clozapine, quetiapine, aripiprazole, risperidone, haloperidol, and amisulpride, PDDs were lower than DDDs. This may indicate the reluctance of clinicians in prescribing higher ranges of dosing, keeping in mind the safety profile of these drugs. For fluphenazine and olanzapine the PDD/DDD ratio was more than one, indicating adequate dosing with these anti

Our results showed a significant difference in costs when compared with findings from other countries. Our average cost of direct medical treatment [4337.28 (58.29 dollars)] was significantly less than what has been documented in the United States[33] (18090 dollars) and European countries [12251 Euro (17937 dollars) and 12864 Euro (16141 dollars) in Germany[35] and 9507 Euro (10135 dollars) in Switzerland[36]] while it was higher than those reported in other Asian countries, such as 6594 dollars in Malaysia[37] (all exchange rates drawn from the Organization for Economic Coo

The current analysis excluded several cost components like indirect costs, including caregiver burdens, lost pro

Quantifying these omitted costs suggests that the real economic burden is likely underestimated. For policymakers this means that the true societal costs could be higher than the direct medical costs reported (4337.28 Indian rupees per patient), emphasizing the need for comprehensive cost approaches that incorporate indirect and non-medical expenses to inform resource allocation and policy planning effectively.

As this study was retrospective in design, the quality of evidence when compared with a prospective study was inferior and subject to confounding concerning various variables with the determination of causation. In the present study we could not assess differences between individual prescribers. Since the research was conducted at a tertiary referral center, prescribing patterns observed may not reflect those in primary care settings or private psychiatric practices. In primary care clinicians might prescribe fewer or different medications, possibly favoring generic or older drugs due to resource constraints. Private practices may prioritize newer, branded drugs, potentially increasing costs and prescribing frequencies. Patients at tertiary centers often have more complex or severe conditions that may lead to higher medication usage and costs. Consequently, the study may overestimate the average costs and medication patterns applicable to the general schizophrenia population, which includes milder cases managed in primary or outpatient settings. In summary, the study’s limited scope and scope of cost analysis indicate that the actual economic impact of schizophrenia treatment is probably higher, particularly when considering broader societal costs and varying prescribing practices across healthcare settings.

Atypical antipsychotics are the mainstay of treatment for schizophrenia in all categories of schizophrenia. Olanzapine was the most frequently prescribed antipsychotic. This study found that concomitant drug prescribing frequency in approximately half of the patients was due to the presence of psychiatric and non-psychiatric comorbidities. Trihe

| 1. | Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;386:743-800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4675] [Cited by in RCA: 4636] [Article Influence: 421.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE Guideline. [cited 8 May 2025]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance. |

| 3. | Zhang H, Sun Y, Zhang D, Zhang C, Chen G. Direct medical costs for patients with schizophrenia: a 4-year cohort study from health insurance claims data in Guangzhou city, Southern China. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2018;12:72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Smith M, Hopkins D, Peveler RC, Holt RI, Woodward M, Ismail K. First- v. second-generation antipsychotics and risk for diabetes in schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192:406-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in RCA: 187] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Uçok A, Gaebel W. Side effects of atypical antipsychotics: a brief overview. World Psychiatry. 2008;7:58-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 131] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Divac N, Prostran M, Jakovcevski I, Cerovac N. Second-generation antipsychotics and extrapyramidal adverse effects. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:656370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | dosReis S, Johnson E, Steinwachs D, Rohde C, Skinner EA, Fahey M, Lehman AF. Antipsychotic treatment patterns and hospitalizations among adults with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008;101:304-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Daumit GL, Crum RM, Guallar E, Powe NR, Primm AB, Steinwachs DM, Ford DE. Outpatient prescriptions for atypical antipsychotics for African Americans, Hispanics, and whites in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:121-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | World Health Organization. World Health Organization Model List of Essential Medicines: 22nd List 2021. Sep 30, 2021. [cited 8 May 2025]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-MHP-HPS-EML-2021.02. |

| 10. | Munjely EJ, R BLN, Punnoose VP. Drug utilization pattern in Schizophrenia. Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol. 2019;8:1572. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 11. | World Health Organization. Introduction to drug utilization research. 2003. [cited 8 May 2025]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42627. |

| 12. | World Health Organization Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment. 2025. [cited 8 May 2025]. Available from: https://www.whocc.no/atc_ddd_index_and_guidelines/guidelines/. |

| 13. | Rode SB, Salankar HV, Verma PR, Sinha U, Ajagallay RK. Pharmacoepidemiological survey of schizophrenia in Central India. Int J Res Med Sci. 2014;2:1058-1062. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Math SB, Chandrashekar CR, Bhugra D. Psychiatric epidemiology in India. Indian J Med Res. 2007;126:183-192. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Sharif S, Al-Shaqra M, Hajjar H, Shamout A, Wess L. Patterns of drug prescribing in a hospital in dubai, United arab emirates. Libyan J Med. 2008;3:10-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Jain S, Khan ZY, Upadhyaya P, Abhijeet K. Assessment of prescription pattern in a private teaching hospital in India. Int J Pharma Sci. 2013;3:219-222. |

| 17. | Mogali SM, Kotinatot BC. Drug utilization study of antipsychotics among schizophrenia patients in a tertiary care teaching hospital: a retrospective observational study. Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol. 2020;9:971-974. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 18. | Balaji R, Sekkizhar M, Asok Kumar, Nirmala P. An observational study of drug utilisation pattern and pharmacovigilance of antipsychotics. Int J Curr Pharm Res. 2017;9:56. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | Kumar S, Chawla S, Bimba HV, Rana P, Dutta S, Kumar S. Analysis of prescribing pattern and techniques of switching over of antipsychotics in outpatients of a tertiary care hospital in Delhi: a prospective, observational study. J Basic Clin Pharm. 2017;8:178-184. |

| 20. | Goel RK, Bhati Y, Dutt HK, and Chopra VS. Prescribing pattern of drugs in the outpatient department of a tertiary care teaching hospital in Ghaziabad, Uttar Pradesh. J App Pharm Sci. 2013;3 suppl 1:S48-S51. |

| 21. | Isah AO, Ross-Degnan D, Quick J, Laing R, Mabadeje AF. The Development of Standard Values for the WHO Drug Use Prescribing Indicators. W Afr J Pharmacol Drug Res. 2001;18:6-11. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 22. | Hazra A, Tripathi SK, Alam MS. Prescribing and dispensing activities at the health facilities of a non-governmental organization. Natl Med J India. 2000;13:177-182. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Wang H, Li N, Zhu H, Xu S, Lu H, Feng Z. Prescription pattern and its influencing factors in Chinese county hospitals: a retrospective cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e63225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rehan HS, Singh C, Tripathi CD, Kela AK. Study of drug utilization pattern in dental OPD at tertiary care teaching hospital. Indian J Dent Res. 2001;12:51-56. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Chandelkar U, Rataboli P. A study of drug prescribing pattern using WHO prescribing indicators in the state of Goa, India. Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol. 2014;3:1057. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Menik HL, Isuru AI, Sewwandi S. A survey: Precepts and practices in drug use indicators at Government Healthcare Facilities: A Hospital-based prospective analysis. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2011;3:165-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Desalegn AA. Assessment of drug use pattern using WHO prescribing indicators at Hawassa University Teaching and Referral Hospital, south Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Tripathy R, Lenka B, Pradhan MR. Prescribing activities at district health care centers of Western Odisha. Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol. 2015;4:419-421. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 29. | Siddiqui RA, Shende TR, Mahajan HM, Borkar A. Antipsychotic medication prescribing trends in a tertiary care hospital. Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol. 2016;5:1417-1420. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 30. | Shaifali I, Karmakar R, Chandra S, Kumar S. Drug utilization audit of antipsychotics using WHO methodology: recommendations for rational prescribing. Int J Basic Clin Pharmacol. 2018;7:2021. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 31. | Grover S, Avasthi A. Anti-psychotic prescription pattern: A preliminary survey of Psychiatrists in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52:257-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Nielsen J, le Quach P, Emborg C, Foldager L, Correll CU. 10-year trends in the treatment and outcomes of patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;122:356-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Fitch K, Iwasaki K, Villa KF. Resource utilization and cost in a commercially insured population with schizophrenia. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2014;7:18-26. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Lahon K, Paramel A, Sharma G. Pharmacoepidemiological study of antipsychotics in the psychiatry unit of a tertiary care hospital: A retrospective descriptive analysis. Int J Nutr Pharmacol Neurol Dis. 2012;2:135-141. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 35. | Frey S. The economic burden of schizophrenia in Germany: a population-based retrospective cohort study using genetic matching. Eur Psychiatry. 2014;29:479-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Pletscher M, Mattli R, von Wyl A, Reich O, Wieser S. The Societal Costs of Schizophrenia in Switzerland. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2015;18:93-103. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Teoh SL, Chong HY, Abdul Aziz S, Chemi N, Othman AR, Md Zaki N, Vanichkulpitak P, Chaiyakunapruk N. The economic burden of schizophrenia in Malaysia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:1979-1987. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/