INTRODUCTION

Common mental disorders (CMDs), including depressive and anxiety disorders, constitute a significant public health problem and are leading causes of disability and impaired quality of life worldwide. The prevalence and disability associated with CMDs are higher among women than men. According to the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2021, a large multinational study that employed a multi-source data analysis approach, including census data, household surveys, and national register information to estimate the health burden of diseases and injuries, the global annual prevalence of depressive and anxiety disorders was estimated at 4.0% and 4.42%, respectively[1]. In women, the prevalence of both conditions was higher when compared to men, with 4.82% vs 3.18% for depressive disorders and 5.53% vs 3.30% for anxiety disorders. Disability metrics from the same study further demonstrate that women experience a greater burden of disability resulting from CMDs. In 2021, depressive disorders were the second highest cause of years lived with disability (YLDs), accounting for 56.3 million YLDs, while anxiety disorders ranked sixth, contributing 42.5 million YLDs. Age-standardized YLD rates per 100000 individuals similarly showed a female preponderance, with 34.1 vs 22.2 for depressive disorders and 26.4 vs 16.1 for anxiety disorders[2]. Regarding disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) per 100000 persons, females displayed rates 64.8% higher than males for anxiety disorders, and 52.0% higher for depressive disorders[3]. According to the World Bank, low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are home to 6.63 billion people, accounting for 82.5% of the global population[4]. These countries bear the largest share of the global burden of CMDs. India is ranked as a lower-middle-income country, with a gross national income per capita ranging from 1146 dollars to 4515 dollars. The National Mental Health Survey of India (NMHS) 2016 reported a weighted prevalence of 2.68% for current depressive disorders and 2.94% for anxiety disorders, translating to roughly 70 million Indian adults suffering from CMDs. The prevalence was highest among women aged 40-59 years, with nearly 60% experiencing disabilities of varying severity[5]. In 2017, depressive disorders contributed the most to total mental disorder DALYs in India (33.8%), followed by anxiety disorders (19.0%), with women having a significantly higher burden of DALYs due to CMDs than men[6].

Despite the substantial public health burden of CMDs in LMICs, the mental health treatment gap - defined as the proportion of patients either not receiving any treatment or not receiving adequate treatment - has been estimated to be as high as 85% in LMICs, compared to only 40% in high-income countries[7]. In India, the NMHS reported a treatment gap of 85.2% for depressive disorders and 84% for anxiety disorders[5]. Additionally, treatment dropout rates in LMICs are high, with approximately 45% of patients discontinuing care, often after only one or two visits[8]. Efforts to reduce the treatment gap in many LMICs have primarily focused on improving access to mental healthcare, such as through the integration of mental health services into primary care, which has been shown to be more effective than usual care in improving outcomes for CMDs[9]. However, addressing the treatment gap also requires careful consideration of contextual factors that influence care delivery in LMICs. For example, a recent qualitative study conducted in southern India, which included a community-based sample of 66 adult women with good awareness of psychiatric models of mental illness and the availability of psychiatric services in their community, identified that fear of stigma, beliefs about the social causes of distress, and doubts about the effectiveness of psychiatric treatment influenced their decision to refuse psychiatric treatment[10]. This review highlights structural and sociocultural issues that shape the outcomes of CMDs among women, with a focus on literature from India. Insights from the Indian context may also inform the delivery of mental healthcare services in other LMICs.

GENDER DISPARITIES IN CMDs

Structural factors

Structural factors refer to deficiencies in infrastructure that act as barriers to seeking healthcare services. Limited access to healthcare facilities poses a significant barrier to treatment adherence among rural women with major depression, often leading to higher rates of medication discontinuation. A study examining outcomes of CMDs in a rural community in South India highlighted lack of transportation and inability to take time off from work as major hindrances in continuing care[11]. The study employed a two-stage diagnostic process and enrolled 144 individuals with major depression in a prospective study design. After six months, 79% of participants remained symptomatic. Geographic distance from healthcare facilities continues to be a critical barrier to care in India, particularly for rural populations. A study on healthcare access in India found that individuals residing more than 5 km from a healthcare facility were significantly less likely to seek treatment, citing travel costs and time as key deterrents[12]. This barrier is even more pronounced in accessing mental health services, which are typically concentrated in urban tertiary centers. The NMHS also highlighted distance and transportation as critical obstacles to care, especially in underserved states[5]. Another factor that considerably hinders women’s access to medical services, particularly in rural areas, is the unavailability of female healthcare personnel at government-administered Primary Health Centers. Findings from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), conducted between 2019 and 2021, revealed that 31.2% of women surveyed regarded the absence of female healthcare providers as a substantial barrier to seeking medical care[13].

Social factors

A review examining the association between poverty and CMDs in six LMICs showed an association between indicators of poverty, such as low income, insecurity, and low educational attainment, and the risk of developing mental disorders, with low educational levels emerging as the most consistent factor[14]. The review also underscored the adversities experienced by women in many developing societies, including poor access to education, physical abuse by husbands, forced marriages, sexual trafficking, fewer job opportunities and, in some contexts, restrictions on participation in activities outside the home. A cross-sectional study evaluating the level of awareness, knowledge and help-seeking attitudes and behaviors related to mental health, as well as their association with socio-demographic characteristics, reported that low educational level among women was linked to poor mental health literacy and delayed help-seeking[15]. While government-led initiatives such as the “Beti Bachao, Beti Padhao” campaign have aimed to enhance girls’ education in India, data from NFHS-5 indicate that many girls discontinue their education after completing school, with relatively few progressing to higher education[13]. The reasons for these dropouts are multifaceted. NFHS-5 data highlights that 21.4% of girls aged 6-17 who dropped out cited a lack of interest in studies as the primary reason. Other contributing factors include the cost of education (20.6%), the need to contribute to household work (13.3%), and early marriage (6.8%).

According to the NFHS-5, women’s labor force participation in India remains notably low[13]. The survey reports that only 25% of women aged 15-49 are currently employed, in stark contrast to 75% of men in the same age group. Among employed women, 46% are engaged in agriculture, while 21% work in production sectors. However, the quality of employment raises concern, as only 25.4% of women who worked in the past 12 months received cash payments for their labor.

Gender roles

In many rural parts of India, women are expected to adhere strictly to traditional gender roles as prescribed by their communities. Patriarchal systems enforce rigid gender roles that prioritize men’s authority over women’s lives[16]. Women are often expected to carry out multiple caregiving responsibilities, including household labor and caregiving, often receiving little social recognition or economic compensation[17]. Studies indicate that gender role stress - stemming from an inability to fulfil culturally prescribed roles - substantially increases the risk of depression and anxiety among women[18]. In addition, women in rural communities are more likely to be burdened by these traditional roles and responsibilities, leaving minimal time for leisure activities and directly impacting the availability and nature of their social support systems[19].

Intimate partner violence

Intimate partner violence (IPV) constitutes a significant public health issue in LMICs, with profound implications for women’s mental health. In India, data from the NFHS-5 revealed that approximately 29.3% of ever-married women aged 15-49 have experienced some form of spousal violence, encompassing physical, sexual, or emotional abuse[20].

The mental health repercussions of IPV are substantial, with affected women exhibiting higher incidences of depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicidal ideation[21]. The chronic stress and trauma associated with IPV often lead to psychological distress, thereby compromising overall well-being. A cross-sectional study involving 980 women aged between 18 years and 60 years found a prevalence of CMDs of 5.7%, with 4.89% of participants indicating exposure to domestic violence during the previous four weeks[22]. Similarly, a cross-sectional survey of 3000 women in Goa, India, showed that IPV was linked to an increased risk of developing CMDs, with the strongest risks observed in women who reported experiencing unwanted sexual activity with their husbands[23].

Despite the severe mental health consequences, help-seeking behavior among Indian women facing IPV remains notably low. The NFHS-5 data indicated that only a small proportion of women seek assistance for domestic violence, underscoring the urgent need for accessible and culturally sensitive support systems[20]. Reluctance to seek help is influenced by factors such as societal stigma, fear of retaliation, economic dependence, and limited awareness of available support services[24,25].

Women’s autonomy

The structural and social factors, including IPV and stigma, have been linked to reduced autonomy in women, thereby affecting the course and outcomes of CMDs. Autonomy is defined as an individual’s ability to shape their environment, along with the technical, social, and psychological ability to obtain and apply information in making decisions related to personal matters[26]. In contrast, agency refers to an individual’s capacity to define personal goals and act upon them independently[27].

A qualitative study embedded within a prospective birth cohort, which included participants from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds, focusing on exploring psychosocial and cultural factors - specifically women’s agency and autonomy - during the perinatal period among mother-infant dyads. The study found that employment was a significant determinant of autonomy in an urban population[28]. Beyond providing an independent source of income, employment enhances women’s self-esteem, expands their exposure to the outside world, increases awareness, and fosters a sense of camaraderie, which is valued irrespective of the wages earned. Additionally, socially well-connected women, who participate in self-help or community groups before marriage, are more confident in decision-making. However, employment can also act as a double-edged sword. A prospective study conducted in low-income communities in Bangalore followed 744 married women aged 16-25 over a 24-month period to investigate the relationship between economic factors and domestic violence. Multivariable logistic regression analysis revealed that women who entered employment between study visits faced an 80% higher risk of physical domestic violence compared to those who remained unemployed, highlighting that changes in women’s economic roles can influence their vulnerability to violence[24].

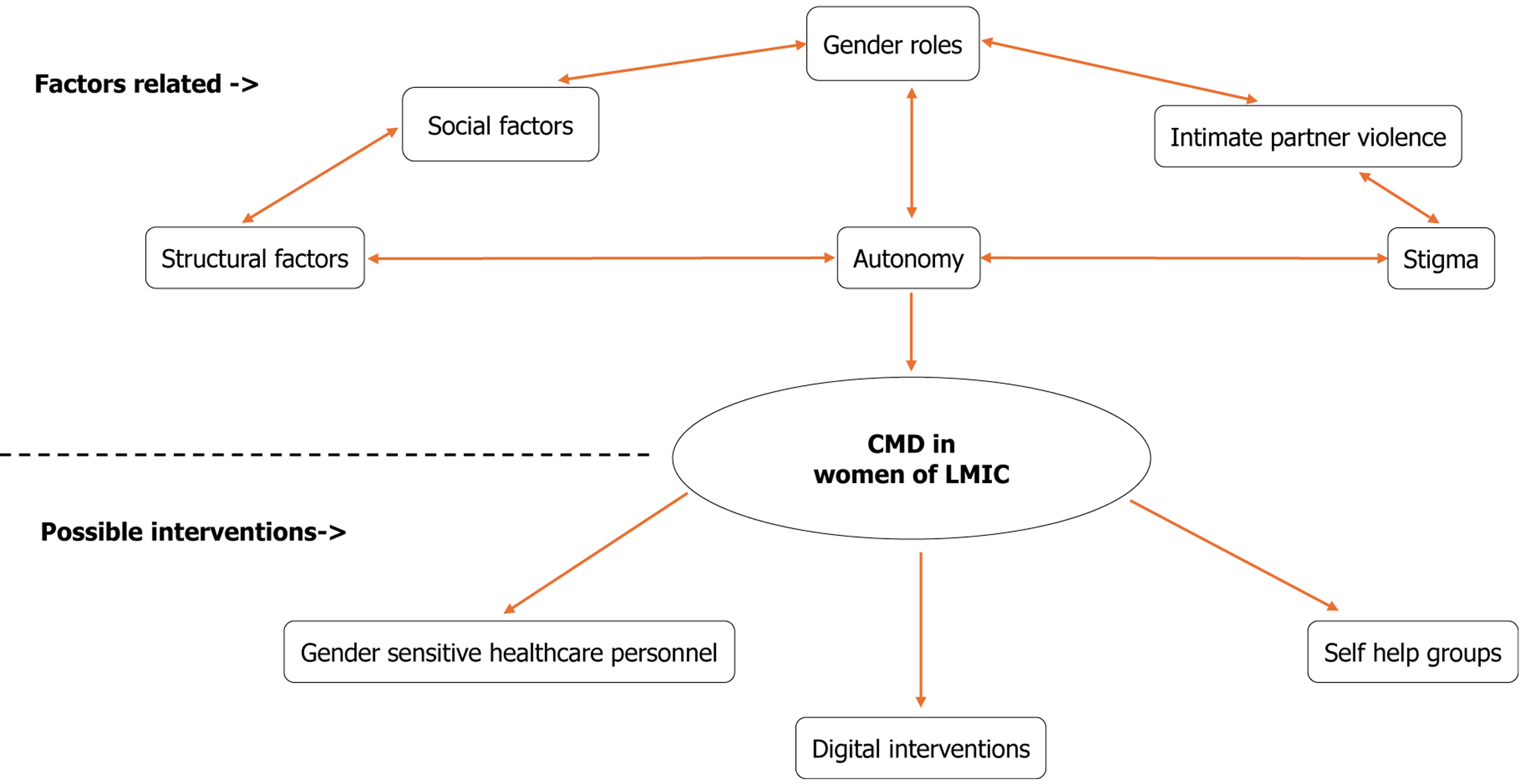

Thus, women in LMICs encounter a complex interplay of structural and social barriers that contribute to the onset, persistence, and poor outcomes of CMDs. Limited access to healthcare infrastructure, particularly in rural areas, results in treatment discontinuation and delayed care. Socioeconomic adversity, including poverty, low educational attainment, and rigid gender roles, further exacerbate mental health risks. IPV, which remains both prevalent yet underreported, significantly increases the burden of CMDs, with stigma, economic dependence, and fear of retaliation impeding help-seeking. These factors collectively reduce women’s autonomy, restricting their ability to make healthcare decisions, especially within patriarchal or joint-family settings. Figure 1 shows the factors related to common mental disorders in women from LMICs with possible interventions.

Figure 1 Factors related to common mental disorders in women from low-and-middle-income countries with possible interventions.

CMD: Common mental disorder; LMIC: Low- and middle-income country.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Integrating mental health interventions with self-help groups

Self-help groups (SHGs) consist of 8-20 women who engage in economic activities such as saving and lending money. Women’s empowerment is a central objective of SHGs, and research suggests that participation in these groups can contribute to moderate gains across economic, political, social, and psychological aspects of empowerment[29]. The familiarity and trust among members, who often belong to the same neighborhood and community, also help reduce stigma around mental health discussions. SHGs typically convene monthly within the participants’ local communities, minimizing travel requirements and enhancing accessibility. These groups facilitate small-scale savings, address local concerns, and organize collective initiatives. By 2020, India had established over 12 million SHGs, influencing the lives of nearly 100 million families[30]. The Ministry of Rural Development implements key programs such as the Deendayal Antyodaya Yojana-National Rural Livelihoods Mission and the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, both of which engage SHGs. Additionally, several other ministries and state-level rural development departments also involve SHGs in their initiatives as needed[31]. Participation in SHG activities that promote economic independence and mobility has the potential to positively impact autonomy, which can contribute to improved psychosocial well-being[32,33]. Initially established as savings and credit collectives, SHGs have gradually evolved to address broader issues, including health awareness and social challenges related to gender and caste discrimination[34,35].

Recent studies have explored the integration of mental health services with traditional SHG activities. A study in Bihar evaluated the impact of the Jeevika program, a rural livelihood initiative involving SHGs, on women’s mental health[36]. The findings indicated that women participating in SHGs exhibited better mental health outcomes compared to non-participants, displaying the positive role of SHGs in supporting psychological well-being. In another study, a pilot mental health intervention was implemented within SHGs in Kollur and Gunnalli villages of Koppal district, Karnataka - a semi-arid, drought-prone region characterized by widespread poverty[37]. The intervention reached over 3500 women across 230 SHGs in 35 villages and included capacity-building for SHG staff, mental health screening and referral, and group counselling. The study demonstrated that SHGs provide a viable framework for integrating mental health care into community-led economic networks, offering a scalable and culturally grounded approach in underprivileged rural contexts. Community-based mental health interventions not only reduce psychological distress but also strengthen women’s social capital[29]. SHG participation provides a platform for improving healthcare access and promoting emotional well-being[38].

Digital interventions

Digital mental health interventions are defined as “information, support, and therapy for mental health conditions delivered through an electronic medium, with the aim of treating, alleviating, or managing mental health symptoms”[39].

In LMICs, such interventions have emerged as a promising and scalable solution to bridge gaps in mental health care, especially in settings with limited access to trained professionals and infrastructure. Their appeal lies in cost-effectiveness, privacy, accessibility, and the potential to reach underserved populations, including women, youth, and rural communities. According to the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India, the country has the second-largest wireless communication subscriber base globally, with over 1.16 billion wireless subscribers[40]. Given the widespread availability of mobile phones, even in low-resource settings, inclusive and user-centered approaches highlight the strong potential of digital platforms to deliver accessible and effective mental health support[39]. Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis suggests that such interventions are particularly beneficial when culturally tailored and developed in collaboration with local stakeholders[41].

The integration of non-specialist facilitators alongside digital technologies has proven effective in decreasing the mental healthcare gap in resource-constrained countries. A systematic review showed that combining human support with digital tools can expand the reach and impact of mental health interventions, thereby improving accessibility for underserved populations[42].

Mobile mental health interventions can be leveraged to address the large depression treatment gap in resource-constrained settings. However, most mental health applications are available only in widely spoken global languages and lack local language options, which greatly limits accessibility for non-English-speaking users[43].

While digital mental health interventions demonstrate considerable promise, they face substantial practical and sociocultural barriers in low-resource environments, such as limited digital literacy and unreliable internet connectivity. A pilot study reported that many rural women in India have minimal experience with smartphones and frequently face network outages, which hinder reliable app usage[38]. A qualitative study from South India showed that users prefer face-to-face consultations, valuing them for their sensitivity and emotional support, suggesting that digital tools should complement rather than replace traditional clinical interactions[44].

Most mental health applications are developed centrally and often lack customization to local cultural contexts. A recent study in rural India designed an app to improve depression outcomes among women attending SHGs, incorporating input from multiple key stakeholders. Initial findings suggest that the app was well accepted by respondents[38].

Gender sensitivity in care

Considering the multiple factors discussed above, gender-related issues are pivotal in shaping the manifestation, experience, and management of CMDs across different communities. Therefore, mental health interventions for CMDs must be culturally sensitive, taking into account local beliefs, language, idioms of distress, and healthcare-seeking behaviors, as well as gender-responsive, with a clear understanding of how gender roles and inequalities affect mental health. Such interventions should address challenges, including lack of decision-making power, gender-based violence (GBV), and constraints on mobility and economic independence.

Programs that train female community health workers, use gender-sensitive communication strategies, or integrate mental health support within women’s SHGs exemplify approaches that reflect both cultural and gender considerations. The presence of trained female healthcare providers has consistently been associated with increased service uptake among women. In rural settings, women often encounter cultural and interpersonal barriers when seeking care from male providers. Expanding the recruitment and training of female community health workers, counsellors, and clinicians enhances access, particularly for sensitive issues such as GBV, reproductive health, and mental health conditions[45]. Stigma, both internalized and within healthcare facilities, represents a major barrier to accessing mental health services. Specifically addressing the detrimental effects of stigma is critical for improving access to care and improving outcomes among women with CMDs.

Interventions such as the Reducing Stigma among Healthcare Providers to Improve mental health services program tackle this issue by incorporating social contact with mental health service users into training for these providers, aiming to improve attitudes and facilitate the integration of mental health care into primary settings[46]. Furthermore, non-specialist health workers in LMICs can effectively deliver mental health care. Training Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHAs) in basic mental health identification and psychoeducation has been found to be both feasible and acceptable. For instance, the Healthier Options through Empowerment study demonstrated that ASHAs could effectively co-facilitate group interventions for perinatal depression when appropriately trained and supervised[47]. Likewise, the Manashanti Sudhar Shodh trial in Goa, which translates to “project to promote mental health” in Konkani, illustrated that lay health counsellors embedded within primary care teams could deliver effective mental health interventions, yielding substantial improvements in outcomes. The primary outcome measured was recovery from CMDs as defined by the International Classification of Diseases-10, six months after recruitment, while secondary outcomes included the severity of depressive and anxiety symptoms[48]. Mental health services delivered by trained nurses and ASHA workers can improve outcomes in CMDs by enhancing the acceptability and accessibility of interventions. In addition, mental health interventions provided by non-specialist health workers from the same community as the clients are less likely to be perceived as stigmatizing, representing a promising approach. Similarly, integrating mental health interventions within the economic empowerment models that underpin SHGs is another strategy with considerable potential that warrants further exploration.

Long-term systemic change in healthcare necessitates the transformation of medical education to include gender-sensitive approaches. The Centre for Enquiry into Health and Allied Themes has collaborated with several medical colleges in Maharashtra, demonstrating that integrating gender into the medical curriculum can shift students’ perspectives on power dynamics, patriarchy, and women’s health. This integration includes modules on GBV, mental health, and sociocultural determinants of health, leading to more compassionate and equitable healthcare providers[49].

These strategies offer promising avenues to overcome the sociocultural barriers that negatively affect women’s mental health, especially among individuals from disadvantaged backgrounds.