Published online Sep 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i9.108465

Revised: May 22, 2025

Accepted: July 11, 2025

Published online: September 19, 2025

Processing time: 133 Days and 20 Hours

Childhood trauma and parental socialization have been postulated as environmental factors of at-risk mental state (ARMS). Parental socialization is the process through which parents shape children’s self-regulation by providing guidance and protection. Although the impact of trauma on ARMS has been theorized, its clinical implications have not yet been fully clarified in adolescence, nor have explanatory models of parenting styles been established.

To investigate the role of traumatic experiences in the appearance of ARMS in the general adolescent population, considering the influence of parental socialization.

A cross-sectional study of 697 adolescents aged 11-15 years was conducted, during which several questionnaires assessing childhood trauma, psychotic symptoms, and parenting styles were administered. The sample was divided into control, low-risk, medium-risk, and high-risk groups.

Some 2.8% (n = 19) of the adolescents presented ARMS and the presence of childhood trauma was associated with an increased risk of ARMS. Furthermore, the presence of abuse was greater in the high-risk and low-risk groups compared to controls. Regarding parental socialization, it was determined that a family socialization style based on greater affection–communication decreased the probability of ARMS. Finally, using PROCESS model 1 (regression-based path analysis that uses ordinary least squares regression), results suggested that low levels of affection and communication may mediate the relationship between childhood trauma and ARMS in adolescents.

These results highlight the importance of the early detection of trauma in preventing ARMS, without forgetting the importance of socialization styles.

Core Tip: This study explores the associations between childhood trauma, parental socialization, and at-risk mental state (ARMS) in adolescents aged 11 to 15. Results suggest that trauma may be linked to a higher likelihood of ARMS, while parenting styles characterized by affection and communication appear to be associated with a lower risk. Low parental affection and communication may play a role in the relationship between trauma and ARMS, highlighting the potential importance of supportive family environments for early identification and prevention efforts.

- Citation: Jovani A, Moliner-Castellano B, Gimeno Vergara R, Benito A, Marí-Sanmillán MI, Castellano-García F, Haro G. Impact of childhood trauma and parental socialization on at-risk mental state in non-clinical adolescents. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(9): 108465

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i9/108465.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i9.108465

Adolescence represents a unique stage of human development characterized by rapid psychosocial growth. Mental disorders are one of the main causes of morbidity during this period[1]. Given that many mental disorders such as psychosis begin in adolescence, early detection could have a considerable impact[2]. Psychotic disorders are multifactorial[3]. Birchwood et al[4] identified a critical period of subthreshold affective, anxious, and attenuated psychotic symptoms that could constitute prodromes prior to the onset of frank psychosis[5]. This period of clinical high-risk was called at-risk mental state (ARMS). Its prevalence is a subject of debate[6] but the latest meta-analysis places it at 1.7%[6].

Childhood trauma has been studied as a risk factor for ARMS[7] and is defined as a stressful life event related to sexual or physical violence, emotional abuse, or neglect[8]. Such adverse childhood experiences include exposure to long-term environmental stressors such as child abuse, domestic violence, and interpersonal losses[9]. One in 4 children suffers abuse or neglect during their childhood, with 78% of cases being neglect in terms of care, 18% physical abuse, and 9% sexual abuse[9]. Psychotic symptoms in these patients are more long-lasting[10]. Of note, a meta-analysis of 6 studies on ARMS in adults found an 87% prevalence of childhood trauma, which was significantly higher than the rates recorded in the control cohorts (42%-60%)[11]. When approaching traumas, the following types are usually considered: Sexual abuse, physical and/or psychological abuse, and physical and/or emotional neglect[12]. In fact, Inyang et al[12] suggested that the general adolescent population should be screened to detect trauma in order to prevent ARMS. In this context, the Davidson Trauma Scale (DTS) showed satisfactory levels of internal consistency in the early detection of trauma[13].

However, most published peer-reviewed literature comes from cross-sectional or longitudinal studies with small sample sizes that did not consider specific trauma variables. Furthermore, previous research has focused on specific pathologies such as schizophrenia and the adult clinical population[14]. Finally, the application of the Clinical High-Risk for Psychosis paradigm in childhood and adolescence remains a topic of debate[15], because psychotic experiences are more common but have less predictive power for psychosis[16].

Parental socialization models are other relevant factors in psychosocial research on psychosis[17]. This is defined as the process through which parents shape the emotional growth, self-regulation, and discipline of children through protection, guidance, and teaching[18]. Although greater attention has been paid to family characteristics as indicators of relapse, evidence has also been published suggesting their role in the risk of psychosis[19]. For example, family criticism has been associated with an increased risk of psychotic symptoms[20]. Conversely, although less explored, positive aspects of family environments such as warmth, have also been identified and are considered protective factors[21]. Parenting styles are typically divided into two main dimensions: Affect and communication, or control and structure[22]. The first dimension highlights the emotional atmosphere in the parent-child relationship, such as warmth and communication quality, while the second focuses on the level of discipline.

Recent studies have examined the role of family support in the development of paranoia in individuals with a history of adverse experiences, highlighting the significance of ensuring protective family environments[23]. In addition, family attachment relationships shape beliefs about oneself and vulnerability to harm, playing a key role in shaping paranoid beliefs during adolescence[24]. Other articles deal with the importance of addressing parental safety behaviors in the evolution of paranoid experiences[25]. One of the validated questionnaires used to assess parental socialization with demonstrated strong reliability is the TXP Parental Socialization Questionnaire for Adolescents (TXP-A)[26].

Given all the above, the main objective of this current article was to establish the impact of traumatic life experiences in the emergence of ARMS in a non-clinical sample of adolescents, while also considering the type of trauma reported and the parental socialization model. Thus, we constructed the following hypotheses: (1) Individuals with ARMS have a greater traumatic burden than those in the control group; and (2) Parental socialization, specifically in terms of affect-communication, suggests its involvement in the debut of ARMS in adolescents with a history of trauma.

This was a cross-sectional, analytical, case-controlled observational study. Non-random sampling was carried out in the general non-clinical adolescent population aged 11-15 years old, from 9 high schools in Castellón, Spain. Deliberate non-probabilistic sampling of the adolescent population was used. A sample of 697 adolescents from the first and second years of compulsory secondary education (ESO) was recruited. The research was conducted in high schools located in Castellón and its surrounding towns (Vila-real and Onda), and the sample included students and families from diverse cultural backgrounds, including South America, Morocco, Russia, China, and Ukraine.

The inclusion criteria were belonging to the first cycle of compulsory ESO, that is, the first or second year of ESO (corresponding to an age of 11-15 years) and having an adequate level of Spanish language. Students who had special educational needs were excluded. Most students who did not participate were excluded due to family refusal, given that only 3 were unable to participate because of an insufficient level of Spanish (n = 1) or an intellectual disability (n = 2).

First, we contacted the directors at the educational centers included in this study. The sample was recruited between September and November 2022, during which time, self-administered questionnaires were individually completed by the adolescents during school hours. About 60-90 minutes were required to respond them. This phase was supported by 4 researchers trained in the tests. The psychometric tests employed were: (1) The Prodromal Questionnaire-Brief (PQ-B), comprising 21 items formulated in a dichotomous (true/false) format to assess prodromal symptoms of positive-type psychosis[27]. If the participant answered in the affirmative to an item, they were asked to indicate the degree of concern or discomfort this experience caused them, using a Likert-type scale with 5 response options. In terms of the psychometric properties of the PQ-B, the test presented an ordinal alpha of 0.95[28] and 0.92 in this sample; (2) The Youth Psychosis At-Risk Questionnaire Brief (YPARQ-B) comprises 28 items in a trichotomous (yes/no/unknown) format. The YPARQ-B assesses self-reported subclinical psychotic experiences in adolescents in the general population and was developed specifically to screen for ARMS symptoms during adolescence[29]. The internal consistency of the total YPARQ-B score was 0.94[28]; (3) The DTS is a self-administered questionnaire consisting of 17 items that evaluate the frequency and severity of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms[13]. It allows 5 response alternatives each for frequency and severity. Adequate levels of internal consistency were found for this questionnaire, with a Cronbach alpha of 0.94[28,30]; (4) The TXP-A was designed for the Spanish population to evaluate parental socialization practices[26] considering affect and communication (including affective and communicative variables and low use of punishment) and control and structure (including roles and limits). The TXP-A showed high reliability (Cronbach Alpha of 0.87, 0.86 in this sample and a test-retest value of 0.94); and (5) In addition, the parents of the participants completed the Neurodevelopment in Adolescence-Parents 1 questionnaire. Our group created this test, which encompasses sociodemographic data (age and academic performance, among others) as well as information related to mental health history.

After requesting parental permission, the participants who exceeded the cut-offs from both the PQ-B and YPARQ-B (this criterion was used to reduce false positives) were interviewed in May and June of 2023, employing the comprehensive assessment of ARMS (CAARMS) individual interview. This semi-structured clinical interview assesses incipient positive symptoms, sensory-perceptive alterations, and thought and language disorders. Each item is rated on a scale of 1-6, where 3 is the cut-off point for ARMS and 6 corresponds to first psychotic episode. The CAARMS is a precise instrument with an area under the curve of 0.85 (95% confidence interval: 0.81-0.88) and a high sensitivity of 0.93 (95% confidence interval: 0.87-0.96)[31]. This interview was conducted by two researchers with experience in its use.

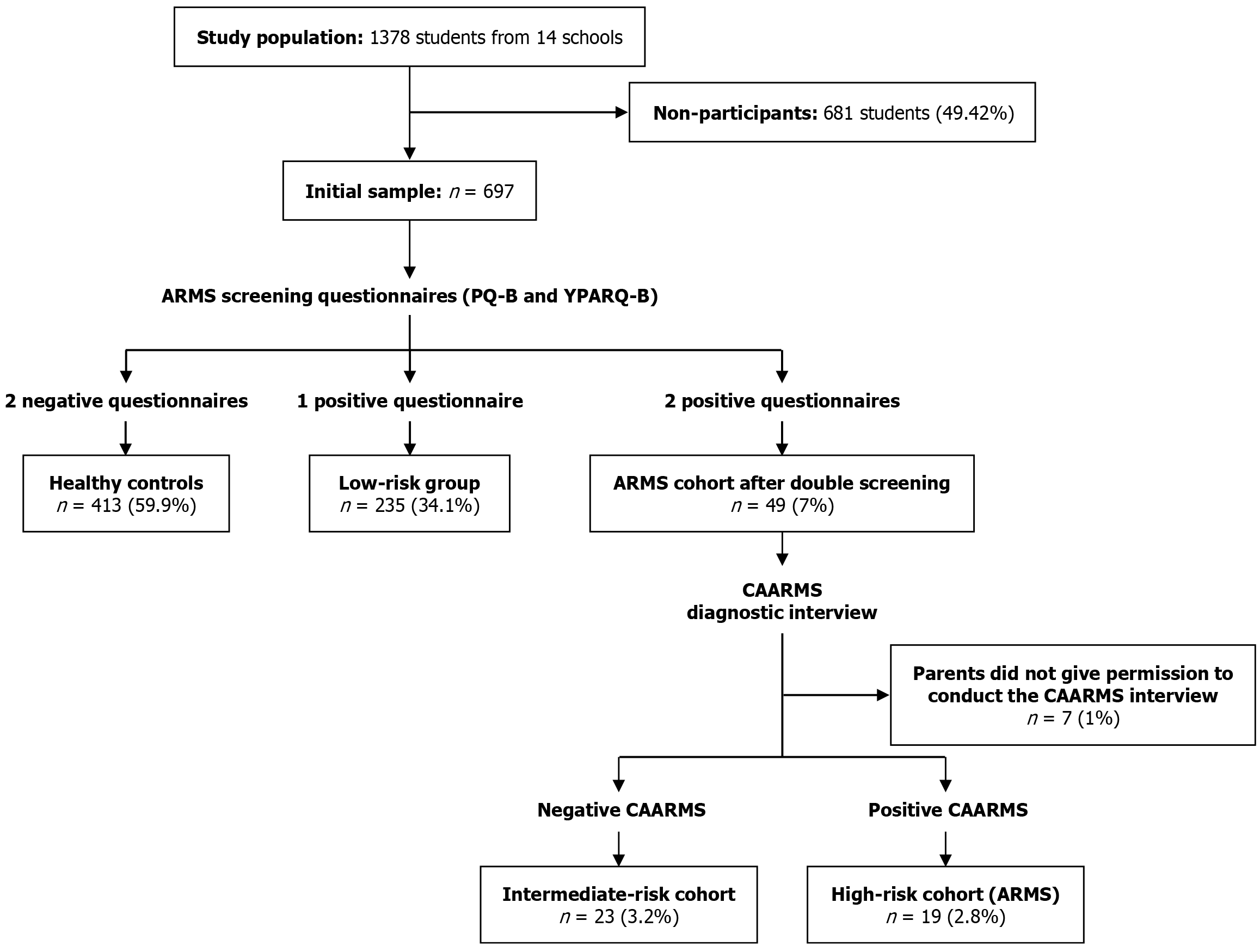

Classification of the initial sample of 697 participants was performed based on the results of the YPARQ-B and PQ-B as well as the CAARMS (Figure 1). Seven participants (1%) were excluded from the study because, even though they exceeded the cut-off points for both questionnaires, their parents did not give permission for the CAARMS interview to be carried out, which prevented their classification into one of the groups. The remaining participants were divided into 4 groups: (1) Healthy controls: Who did not exceed the cut-off points on the PQ-B or YPARQ-B (n = 413; 59.9% of the initial sample); (2) Low-risk group: Who exceeded the cut-off point in either the PQ-B or YPARQ-B, but not both (n = 235; 34.1%); (3) Intermediate-risk group: Who exceeded the cut-off points on both the PQ-B and YPARQ-B but did not meet any diagnostic criteria for ARMS on the CAARMS interview (n = 23; 3.2%); and (4) High-risk group (ARMS): Who exceeded the cut-off points of both the PQ-B and YPARQ-B and also met at least one diagnostic criterion for ARMS in the CAARMS interview (n = 19; 2.8%).

Epidat 3.1 software[32] was used to calculate that, to evaluate the prevalence of the ARMS, which is 1.7% in the general adolescent population, with a precision of 1% and considering participants aged 11-15 years living in Castellon as the reference population (n = 8249)[33], the required sample size would need to be 596 individuals. Likewise, G*Power software (version 3.1.9.4) was used to calculate that the sample size required for multivariate analysis of variance would need to be 296 participants when applying an effect size 0.02, power of 0.80, and alpha of 0.05, with 4 groups and 4 variables. The data were analyzed with SPSS software (version 27; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States).

After the exploratory and descriptive analysis and verification that the statistical assumptions were met, the relationships between the variables evaluated were studied using χ2 tests for categorical variables and correlations for quantitative variables. multivariate analysis of variance and subsequent analysis of variance tests were used to analyze the differences between the study groups (the control, low-risk, intermediate-risk, and high-risk of ARMS groups) for the quantitative variables.

Given the difference in sample size between the different study cohorts, Bonferroni correction was used and considering these results, ordinal logistic regression was then performed to try to predict inclusion in each of the study groups. The group variable to which the participant belonged was considered ordinal, given that each group had a higher ARMS score than the previous one. Likewise, the data were modelled using the PROCESS v3.4 plugin[34] for SPSS to assess the relationships between ARMS, trauma, and parental socialization. PROCESS uses regression-based path analysis as a means of estimating various effects of interest (direct and indirect, conditional, and unconditional), using ordinary least squares regression to estimate the model parameters[34]. Model 1 was used to test moderation and model 4 was used to test mediation.

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the adolescents included in this study. Some 51.7% were female (n = 356), and the mean sample age was 12.6 years (SD = 0.7). A total of 57.4% (n = 396) belonged to a public school, 40.1% (n = 277) to a charter (state-subsidized) school, while only 2.5% (n = 17) belonged to a private school. Regarding academic performance, the mean grades obtained by most of the sample (70.2%; n = 390) were a “pass” (25.9%; n = 144) or “exceptional” (44.3%; n = 246). A total of 19.2% (n = 107) had, at some point, received care from mental health services. As shown in Table 1, there were no differences between the groups studied for most of the sociodemographic variables, except that there were more boys in the control group than in the low-risk group.

| Characteristics | Overall sample | Controls | Low-risk | Intermediate-risk | High-risk (ARMS) | χ2/F, P value | ES, CTR | |

| Sex | Male | 333 (48.3) | 221 (53.5) | 95 (40.6) | 9 (39.1) | 8 (42.1) | 11.11, 0.011a | 0.127, 3.3/-2.9, -3.3/2.9 |

| Female | 356 (51.7) | 192 (46.5) | 139 (59.4) | 14 (60.9) | 11 (57.9) | |||

| Age (years) | - | 12.6 (0.7) | 12.6 (0.7) | 12.6 (0.7) | 12.6 (0.4) | 12.6 (0.7) | 0.25, 0.860 | 0.001 |

| School type | Public | 396 (57.4) | 237 (57.4) | 136 (57.9) | 11 (47.8) | 12 (63.2) | 3.13, 0.792 | 0.048 |

| Charter | 277 (40.1) | 168 (40.7) | 91 (38.7) | 11 (47.8) | 7 (36.8) | |||

| Private | 17 (2.5) | 8 (1.9) | 8 (3.4) | 1 (4.3) | 0 (0) | |||

| School year | 1st CSE | 350 (50.7) | 205 (49.6) | 121 (51.5) | 14 (60.9) | 10 (52.6) | 1.22, 0.747 | 0.042 |

| 2nd CSE | 340 (49.3) | 208 (50.4) | 114 (48.5) | 9 (39.1) | 9 (47.4) | |||

| Academic performance | Fail | 33 (5.9) | 14 (4.3) | 17 (8.7) | 1 (5) | 1 (6.7) | 11.09, 0.269 | 0.082 |

| Pass | 144 (25.9) | 77 (23.8) | 55 (28.1) | 5 (25) | 7 (46.7) | |||

| Exceptional | 246 (44.3) | 148 (45.7) | 85 (43.4) | 8 (40) | 5 (33.3) | |||

| Outstanding | 132 (23.8) | 85 (26.2) | 39 (19.9) | 6 (30) | 2 (13.3) | |||

| Prior mental health follow-up | No | 451 (80.8) | 269 (82) | 153 (78.5) | 17 (85) | 12 (80) | 1.23, 0.753 | 0.047 |

| Yes | 107 (19.2) | 59 (18) | 42 (21.5) | 3 (15) | 3 (20) | |||

| Psychiatric medication | No | 537 (95.9) | 313 (95.4) | 190 (96.4) | 20 (100) | 14 (93.3) | 1.44, 0.727 | 0.051 |

| Yes | 23 (4.1) | 15 (4.6) | 7 (3.6) | 0 (0) | 1 (6.7) | |||

| Mental disorder | No | 614 (89) | 376 (91) | 202 (86) | 20 (87) | 16 (84.2) | 4.51, 0.204 | 0.081 |

| Yes | 76 (11) | 37 (9) | 33 (14) | 3 (13) | 3 (15.8) | |||

| Substance consumption | No | 673 (97.5) | 409 (99) | 224 (95.3) | 23 (100) | 17 (89.5) | 14.37, 0.015a | 0.144, 3.1/-2.7/-2.3, -3.1/2.7/2.3 |

| Yes | 17 (2.5) | 4 (1) | 11 (4.7) | 0 (0) | 2 (10.5) | |||

| Video game addiction | No | 557 (99.5) | 327 (99.7) | 195 (99) | 20 (100) | 15 (100) | 1.36, 0.639 | 0.049 |

| Yes | 3 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||

| Bullying | Never | 414 (75.1) | 261 (80.6) | 133 (68.6) | 11 (57.9) | 9 (64.3) | 16.09, 0.015a | 0.121, 3.5/-2.6, -2.1, -2.6/2.5 |

| Maybe | 79 (14.3) | 38 (11.7) | 32 (16.5) | 5 (26.3) | 4 (28.6) | |||

| Yes | 58 (10.5) | 25 (7.7) | 29 (14.9) | 3 (15.8) | 1 (7.1) | |||

| Needs mental health care | No | 459 (83) | 283 (87.1) | 154 (79) | 13 (68.4) | 9 (64.3) | 12.90, 0.048a | 0.108, 3, -2.7 |

| Maybe | 57 (10.3) | 24 (7.4) | 26 (13.3) | 4 (21.1) | 3 (21.4) | |||

| Yes | 37 (6.7) | 18 (5.5) | 15 (7.7) | 2 (10.5) | 2 (14.3) | |||

In terms of the clinical variables (Table 1), there were significant differences in the perceptions of the parents of the participants regarding substance use, bullying, and the need for mental health help by their child. Specifically, the corrected standardized residuals indicated that the intermediate and high-risk (ARMS) groups presented a higher proportion of substance consumption than the control group. Compared to the low-risk group, a greater proportion of the control group replied “never” or “perhaps” when asked if they had suffered bullying and the low-risk group had experienced bullying in a higher proportion than the control group. Finally, in the control group, a greater proportion of the parents of participants considered that their child did not need mental health care, compared to those who thought their child “perhaps” needed this kind of support.

Table 2 shows comparisons of the variables related to trauma. The control group scored lower on the DTS scale than all the other groups and the low-risk group scored lower than the intermediate and high-risk groups. In fact, the three risk groups (low, intermediate, and high) more frequently exceed the DTS cut-off point than the control group. In other words, the presence of trauma was greater in these three groups than in the control group. Regarding the specific traumas experienced (Table 2), the low-risk group had experienced physical or emotional neglect more frequently than the control group, while the low and high-risk groups had experienced a greater frequency of abuse than the control group. Finally, the control group comprised more individuals who had not experienced any traumas.

| Characteristics | Overall sample | Controls | Low-risk | Intermediate-risk | High-risk (ARMS) | χ2/F P value | ES CTR/significant differences | |

| DTS (total score), mean ± SD | 28.45 ± 27.32 | 16.06 ± 18.01 | 42.76 ± 25.44 | 69.91 ± 33.80 | 71.11 ± 31.15 | 128.03, < 0.001c | 0.363, C < B/C < I/C < A/B < I/B < A | |

| DTS (cut-off point) | No | 480 (70.8) | 363 (89.2) | 111 (48.5) | 4 (17.4) | 2 (10.5) | 186.90, < 0.001c | 0.525, 12.9/-9.1/-5.7/-5.9 -12.0/9.1/5.7/5.9 |

| Yes | 198 (29.2) | 44 (10.8) | 118 (51.5) | 19 (82.6) | 17 (89.5) | |||

| Physical/emotional neglect | No | 646 (94) | 395 (95.9) | 212 (91) | 20 (87) | 19 (100) | 9.59, 0.032a | 0.118, 2.5/-2.4, -2.5/2.4 |

| Yes | 41 (6) | 17 (4.1) | 21 (9) | 3 (13) | 0 (0) | |||

| Sexual abuse | No | 681 (99.1) | 411 (99.8) | 228 (97.9) | 23 (100) | 19 (100) | 6.62, 0.097 | 0.098 |

| Yes | 6 (0.9) | 1 (0.2) | 5 (2.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||

| Abuse | No | 632 (92) | 392 (95.1) | 207 (88.8) | 19 (82.6) | 14 (73.7) | 20.10, 0.001b | 0.193, 3.7/-2.2/-3, -3.7/2.2/1.7 |

| Yes | 55 (8) | 20 (4.9) | 26 (11.2) | 4 (17.4) | 5 (26.3) | |||

| Natural disaster | No | 673 (98) | 400 (97.1) | 231 (99.1) | 23 (100) | 19 (100) | 4.07, 0.203 | 0.077 |

| Yes | 14 (2) | 12 (2.9) | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||

| Interpersonal event | No | 673 (98) | 407 (98.8) | 226 (97) | 22 (95.7) | 18 (94.7) | 4.09, 0.180 | 0.077 |

| Yes | 14 (2) | 5 (1.2) | 7 (3) | 1 (4.3) | 1 (5.3) | |||

| Grief of a death | No | 560 (81.5) | 324 (78.6) | 197 (84.5) | 21 (91.3) | 18 (94.7) | 7.34, 0.056 | 0.103 |

| Yes | 127 (18.5) | 88 (21.4) | 36 (15.5) | 2 (8.7) | 1 (5.3) | |||

| Grief without a death | No | 667 (97.1) | 403 (97.8) | 223 (95.7) | 22 (95.7) | 19 (100) | 3.07, 0.363 | 0.067 |

| Yes | 20 (2.9) | 9 (2.2) | 10 (4.3) | 1 (4.3) | 0 (0) | |||

| Interpersonal problems | No | 635 (92.4) | 382 (92.7) | 215 (92.3) | 20 (87) | 18 (94.7) | 1.18, 0.778 | 0.042 |

| Yes | 52 (7.6) | 30 (7.3) | 18 (7.7) | 3 (13) | 1 (5.3) | |||

| Others | No | 552 (80.3) | 343 (83.3) | 180 (77.3) | 17 (73.9) | 12 (63.2) | 7.77, 0.049a | 0.106, 3, -2.3 |

| Yes | 135 (19.7) | 69 (16.7) | 53 (22.7) | 6 (26.1) | 7 (36.8) | |||

Table 3 presents the scores for the parental socialization questionnaire. The control group scored higher for affect and communication than the other three groups and in turn, the low-risk group had a higher score than the intermediate and high-risk groups. Additionally, the control group also scored higher for control and structure than the low-risk group.

| Characteristics | Overall sample | Controls | Low-risk | Intermediate-risk | High-risk (ARMS) | F, P value | ES, significant differences |

| Affection and communication | 75.18 ± 9.78 | 77.65 ± 7.82 | 72.02 ± 10.76 | 70.70 ± 13.99 | 66.05 ± 11.53 | 26.69, < 0.001b | 0.106, C > B/C > I/C > A/L > A |

| Control and structure | 36 ± 5.08 | 36.49 ± 5.01 | 35.18 ± 5.27 | 36.87 ± 3.87 | 34.42 ± 4.24 | 3.58, 0.014a | 0.016, C > B |

As shown in Table 4, all the variables with differences between the groups could be individually used to predict the group to which the participant had belonged. However, when we evaluated the model adjusted for the remaining variables, only the affect and communication score, DTS score, and presence of other traumas had still maintained this predictive power.

| Variable | Unadjusted model | Adjusted model | ||||

| OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Sex (female) | 1.659 | 1.225-2.247 | 0.001b | 1.004 | 0.676-1.492 | 0.984 |

| Substance use | 3.568 | 1.489-8.550 | 0.004b | 1.735 | 0.581-5.178 | 0.323 |

| Bullying | 2.110 | 1.246-3.571 | 0.005b | 1.402 | 0.740-2.653 | 0.300 |

| Potential mental health need | 2.297 | 1.345-3.922 | 0.002b | 1.543 | 0.840-2.836 | 0.162 |

| Affect and communication | 0.937 | 0.922-0.952 | < 0.001c | 0.971 | 0.946-0.997 | 0.029a |

| Control and structure | 0.959 | 0.932-0.987 | 0.005b | 1.017 | 0.969-1.067 | 0.499 |

| DTS score | 1.055 | 1.047-1.063 | < 0.001c | 1.046 | 1.037-1.056 | < 0.001c |

| Physical-emotional neglect | 2.037 | 1.121-3.702 | 0.020a | 1.039 | 0.463-2.328 | 0.927 |

| Abuse | 2.996 | 1.756-5.110 | < 0.001c | 1.931 | 0.999-3.734 | 0.050 |

| Other traumas | 1.607 | 1.111-2.325 | 0.012a | 1.785 | 1.091-2.919 | 0.021a |

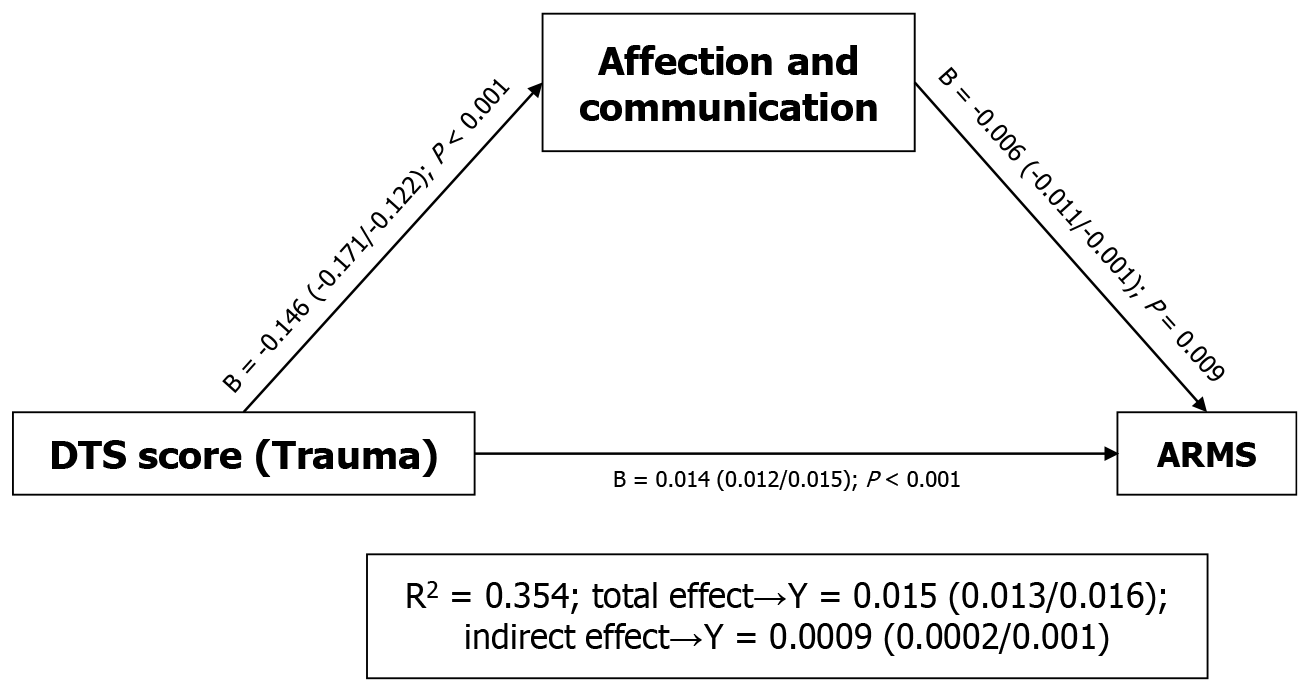

To evaluate the role of parental socialization on the relationship between trauma (DTS score) and ARMS (according to the participant classification group), we tested whether the affect and communication variable acted as a moderator (model 1) or mediator (model 4) in said relationship. The data adjusted better to the mediation model shown in Figure 2. Of note, the quantitative variable of trauma was taken into account by employing the DTS score rather than the score from each specific trauma, given that the latter is a categorical variable that results in the same data.

In this study, we examined the potential risk of childhood trauma on having ARMS in a large sample of the general adolescent population while also considering parental socialization style. Likewise, the prevalence of ARMS in non-clinical adolescents was assessed. We found that 34.1% (n = 235) of adolescents in our sample presented attenuated symptoms, albeit with varying degrees of risk, which were classified as low, intermediate, or high. The high-risk group (ARMS) comprised 2.8% of adolescents (n = 19). The participants were classified into groups according to previously published academic literature: Fonseca-Pedrero et al[35] classified individuals into 6 groups of increasing latent risk, while others[36] classified them into 3 groups, to try to compare the impact of trauma and parental socialization regarding the severity of psychotic symptomatology.

The prevalence of ARMS in the general non-clinical adolescent population is a topic of epidemiological debate, with disparity because of the different evaluation methods employed[6]. Furthermore, some previous articles have only focused on the prevalence of transition to psychosis[37]. Classically, the prevalence of ARMS ranges from 1 to 8%[38], with some studies suggesting that it is 7.3%[16]. Nonetheless, the most recent meta-analysis[6] places it at 1.7%, one percentage point lower than the prevalence we report in this current work. A possible explanation could be the younger mean age in our sample. Another reason could be that the parents of healthy children declined to participate in order to avoid social stigma.

One of our main findings was that the combination of childhood trauma and a parenting style with little affect and communication is associated with greater severity of psychotic symptoms. In line with previous findings[39], the results of this present study showed that 78.9% of adolescents with ARMS (n = 15) had reported some form of childhood trauma. Furthermore, in support of our first hypothesis, the distribution of reports of having experienced trauma across the groups was statistically significant, with each successively higher risk group showing a higher percentage of traumatic experiences, culminating in the ARMS group. It has been postulated that trauma experienced during childhood can lead to negative perceptions about oneself, others, and the environment[11]. In this sense, early bullying or physical abuse can foster mistrust towards others, which in turn, could contribute to the debut of paranoid ideas or self-referential thoughts[11]. Moreover, there is also evidence for the role of biological mechanisms in the appearance of symptoms. First, the stress vulnerability model[39] explains how biological changes related to stress exposure from trauma interact with underlying predisposing vulnerability, generating a cytokine imbalance[40]. Second, the neurodevelopmental trauma model focuses on the causal role of childhood trauma in the development of psychosis, suggesting that the increased stress sensitivity seen in psychotic patients is related to neurological brain changes after exposure to trauma[41].

From among the different types of childhood trauma, our study considered physical and emotional neglect, physical and psychological abuse, sexual abuse, trauma derived from adverse natural events, and trauma caused by grief and interpersonal trauma. Thus, we included trauma categories that are usually considered unusual in order to consider the main life events adolescents considered traumatic[12]. Here, we observed a higher prevalence of physical and ARMS emotional neglect and of abuse in the low-risk group when compared to the controls. Physical neglect is defined as the inability of the caregiver to provide basic physical care such as hygiene, food, shelter, and medical care[42]. In contrast, emotional neglect refers to inadequacy in terms of attending to emotional needs and providing individual attention[42]. To date, the prevalence of care neglect in children with ARMS has been little studied, despite its potential clinical impact[43].

Surprisingly, we did not obtain statistically significant differences between the groups regarding sexual abuse. In our sample, 0.9% (n = 6) of the adolescents reported having been sexually abused, all of whom were female. Sexual abuse is usually postulated as the type of trauma most associated with the severity of psychotic symptoms and so the result we obtained here may be the result of underdiagnosis, given that previous evidence suggests that the prevalence is higher (13.5% in women and 5.6% in men[44]). The low reported prevalence in our study may reflect underreporting, possibly due to cultural stigma surrounding disclosure of sexual abuse, which can inhibit honest reporting, especially in adolescent populations[45]. Additionally, methodological factors such as the sensitivity of the questionnaire used may have limited detection, because standardized measures might not fully capture the complexity or secrecy of sexual abuse experiences.

In this context, emotional neglect may be related to a certain style of parental socialization[46]. The influence of family from the first stages of life, through attachment, on the correct development and upbringing of children has already been described[47]. Attachment is defined as the emotional connection formed based on the unconditional love and care provided by parents to their children. In this sense, previous studies describe how insecure attachment promotes a greater risk of experiencing early psychotic experiences, as well as worse clinical variables in adulthood[48]. In fact, people with schizophrenia spectrum diagnoses have reported higher levels of insecure attachment[49]. Moreover, recent literature establishes that insecure attachment is related to psychotic experiences both in non-clinical populations[50] and clinical groups[51].

The results of the present study showed a negative relationship between parental socialization style based on affect and communication and ARMS. This supports the second of our proposed hypotheses, given that the use of this educational style by parents may act as a protective factor against ARMS. However, we did not detect any conclusive differences between the high-risk and control groups in terms of the parental socialization style based on control and structure. Moreover, in addition to the association between childhood trauma and the emergence of the early psychotic symptoms described above, extensive academic literature has linked the latter to having been parented with a precarious socialization style in childhood[52]. In this sense, and in agreement with our data, some studies have shown that solid family support characterized by high affect and communication would act as a protective element against psychotic symptoms[52].

Although this study was conducted in the specific sociocultural context of Spain -where public schools include a high proportion of culturally diverse students (mainly from Morocco, Romania, China, Ecuador, and Bolivia[53]) - certain cultural factors may have influenced the observed outcomes. Spanish parenting is generally characterized by familism, emotional closeness, and strong involvement in the educational process, combining affection with clear boundaries and fostering open, bidirectional communication[54]. This style, often described as democratic or indulgent, may have shaped adolescents’ responses in this study. In contrast, other cultural settings may emphasize different parenting norms - such as early autonomy in the United States and United Kingdom, egalitarian approaches in Nordic countries, or more authoritarian parenting in some Asian societies[55]. Latin American cultures share elements of familism, though with contextual differences[56]. Recent Spanish research also highlights adolescents’ perceptions of high maternal involvement and family control[57,58], which may further contextualize our findings. These cultural dynamics, together with the use of non-random sampling, underscore the importance of replicating this study in other populations to assess the generalizability of our results.

Our study uncovered the mediating role of low family affect and communication in the relationship between adverse childhood experiences and the genesis of ARMS. Consequently, poor affective family dynamics should be regarded as a warning sign. Here, it is essential to point out the difference between the mediating and moderating models[34], established by Baron and Kenny[59] in 1986. In a mediation model, variable X affects variable Y because X affects the mediator variable M, and this causal effect then transmits the effect of X to Y through the effect of M on Y[60]. Mediation analysis has been around in various forms for at least 70 years but Baron and Kenny[59] popularized an approach to using it employing easy to understand regression analysis principles[60]. Subsequently, there has been increasing emphasis on estimating the indirect effect using different methods, the most popular being the bootstrap confidence interval[61]. Whereas mediation analysis focuses on how a causal effect operates, moderation analysis is used to address, when, or under what circumstances, or for what types of people that effect exists and at what magnitude[60]. These models are also called interaction models and the most popular methods for testing them is simple slope analysis, the pick-a-point approach, or spotlight analysis[60]. An alternative approach is the use of the Johnson-Neyman technique[62].

In the context of the above, our moderation model examines when or under what conditions the relationship between trauma and ARMS changes based on parenting styles, while a mediation model focuses on explaining how trauma affects ARMS through parenting styles. In this sense, promoting an adequate family environment characterized by empathy and in which problems can be verbalized, can have positive effects on mental health. In other words, this aforementioned approach helps to prevent the opposite situation in which everyday problems are not openly expressed, allowing them to become chronic and a substrate for other, more difficult problems[63]. From this perspective, it becomes important to work with the family members of individuals with ARMS to promote adaptive family functioning.

In terms of prevention, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends screening all adolescents at age 12 to identify those at risk of depression and/or suicidal ideation[64]. However, the ARMS model usually assesses the presence of psychosis in help-seeking subjects[65]. Given that not all individuals at risk of developing psychotic-spectrum pathologies present significant distress, this criterion leaves individuals with symptoms barely perceptible by community members, undetected. This is when family and school counsellors become more relevant. Nonetheless, it is important that this be done by optimizing screening strategies so that we do not inadvertently fall into overdiagnosis. In this sense, addressing the history of trauma as well as parental socialization would provide valuable information.

This present research is subject to some limitations. First, most of the metrics used relied on adolescent self-reports, which may have introduced bias, especially in the assessment of trauma and parenting styles. Perceptions can be affected by current symptoms or memory distortions, potentially leading to under or overreporting. Future studies should consider multi-informant approaches to improve the validity of these assessments. However, to minimize this bias, sociodemographic information provided by parents was available and the CAARMS clinical interview was conducted with the individuals from our sample at the highest risk. Furthermore, different studies have shown the reliability of self-reports in the adolescent population[66]. Another limitation was the disproportion between the study group sample sizes because, logically, as the risk of psychosis increases the prevalence in the general population decreases. We minimized this bias by applying the Bonferroni correction. However, this disproportion increases the likelihood of type II errors, so the results must still be interpreted with caution. Another potential source of bias may be the failure to assess, and therefore to include in the regression models, pre-study factors such as socioeconomic status, family structure, or comorbid mental disorders, which could influence the results. Also, the cross-sectional design of the study prevents us from establishing causal relationships or determining the temporal order of the variables (trauma, parental socialization, and ARMS). Although the associations are theoretically supported, it remains unclear whether parenting style influences ARMS, or whether emerging symptoms affect how parenting is perceived. Longitudinal studies are needed to clarify these relationships. The exclusion of 7 possible ARMS cases because the families refused to allow completion of the CAARMS interview was also a limitation. Furthermore, because of perceived social stigma, affected individuals could choose to hide their symptoms and discomfort and not seek help. Moreover, the fact that individuals with cognitive difficulties or low Spanish proficiency (e.g. immigrants) were excluded, was a limitation. Nonetheless, only 3 students were excluded for these reasons. Finally, future longitudinal studies will be needed to validate mediation pathways and track ARMS progression over time.

This study showed that low affect-communication parental socialization is likely involved in the debut of the ARMS in adolescents with a history of childhood trauma. Thus, the presence of traumatic events was associated with greater risk of ARMS while a parental approach characterized by high affect and communication was found to reduce the chances of developing ARMS. These findings highlight the relevance of identifying trauma and emotionally dysfunctional family dynamics - characterized by low emotional warmth, poor communication, and limited parental support or empathy - early in adolescence to avoid ARMS.

| 1. | Kieling C, Buchweitz C, Caye A, Silvani J, Ameis SH, Brunoni AR, Cost KT, Courtney DB, Georgiades K, Merikangas KR, Henderson JL, Polanczyk GV, Rohde LA, Salum GA, Szatmari P. Worldwide Prevalence and Disability From Mental Disorders Across Childhood and Adolescence: Evidence From the Global Burden of Disease Study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2024;81:347-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 301] [Article Influence: 150.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lustig S, Kaess M, Schnyder N, Michel C, Brunner R, Tubiana A, Kahn JP, Sarchiapone M, Hoven CW, Barzilay S, Apter A, Balazs J, Bobes J, Saiz PA, Cozman D, Cotter P, Kereszteny A, Podlogar T, Postuvan V, Värnik A, Resch F, Carli V, Wasserman D. The impact of school-based screening on service use in adolescents at risk for mental health problems and risk-behaviour. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2023;32:1745-1754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kotlicka-Antczak M, Podgórski M, Oliver D, Maric NP, Valmaggia L, Fusar-Poli P. Worldwide implementation of clinical services for the prevention of psychosis: The IEPA early intervention in mental health survey. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2020;14:741-750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Birchwood M, Todd P, Jackson C. Early intervention in psychosis. The critical period hypothesis. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1998;172:53-59. [PubMed] |

| 5. | McGorry PD. Early intervention in psychosis: obvious, effective, overdue. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2015;203:310-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 16.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Salazar de Pablo G, Woods SW, Drymonitou G, de Diego H, Fusar-Poli P. Prevalence of Individuals at Clinical High-Risk of Psychosis in the General Population and Clinical Samples: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Brain Sci. 2021;11:1544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Bi XJ, Lv XM, Ai XY, Sun MM, Cui KY, Yang LM, Wang LN, Yin AH, Liu LF. Childhood trauma interacted with BDNF Val66Met influence schizophrenic symptoms. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e0160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bhavsar V, Boydell J, McGuire P, Harris V, Hotopf M, Hatch SL, MacCabe JH, Morgan C. Childhood abuse and psychotic experiences - evidence for mediation by adulthood adverse life events. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2019;28:300-309. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Vila-Badia R, Butjosa A, Del Cacho N, Serra-Arumí C, Esteban-Sanjusto M, Ochoa S, Usall J. Types, prevalence and gender differences of childhood trauma in first-episode psychosis. What is the evidence that childhood trauma is related to symptoms and functional outcomes in first episode psychosis? A systematic review. Schizophr Res. 2021;228:159-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kaufman J, Torbey S. Child maltreatment and psychosis. Neurobiol Dis. 2019;131:104378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kraan T, Velthorst E, Smit F, de Haan L, van der Gaag M. Trauma and recent life events in individuals at ultra high risk for psychosis: review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2015;161:143-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 126] [Cited by in RCA: 145] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Inyang B, Gondal FJ, Abah GA, Minnal Dhandapani M, Manne M, Khanna M, Challa S, Kabeil AS, Mohammed L. The Role of Childhood Trauma in Psychosis and Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2022;14:e21466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Guerra C, Martínez P, Ahumada C, Díaz M. Análisis Psicométrico Preliminar de la Escala de Trauma de Davidson en adolescentes Chilenos. Summa Psicológica. 2013;10:41-48. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Stowkowy J, Liu L, Cadenhead KS, Cannon TD, Cornblatt BA, McGlashan TH, Perkins DO, Seidman LJ, Tsuang MT, Walker EF, Woods SW, Bearden CE, Mathalon DH, Addington J. Early traumatic experiences, perceived discrimination and conversion to psychosis in those at clinical high risk for psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51:497-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Raballo A, Poletti M, Preti A. Clinical High Risk for Psychosis (CHR-P) in children and adolescents: a roadmap to strengthen clinical utility through conceptual clarity. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2024;33:1997-1999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Schultze-Lutter F, Walger P, Franscini M, Traber-Walker N, Osman N, Walger H, Schimmelmann BG, Flückiger R, Michel C. Clinical high-risk criteria of psychosis in 8-17-year-old community subjects and inpatients not suspected of developing psychosis. World J Psychiatry. 2022;12:425-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 17. | Hinojosa-Marqués L, Domínguez-Martínez T, Barrantes-Vidal N. Family environmental factors in at-risk mental states for psychosis. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2022;29:424-454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lin Z, Zhou Z, Zhu L, Wu W. Parenting styles, empathy and aggressive behavior in preschool children: an examination of mediating mechanisms. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1243623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | O'Driscoll C, Sener SB, Angmark A, Shaikh M. Caregiving processes and expressed emotion in psychosis, a cross-cultural, meta-analytic review. Schizophr Res. 2019;208:8-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Wüsten C, Lincoln TM. The association of family functioning and psychosis proneness in five countries that differ in cultural values and family structures. Psychiatry Res. 2017;253:158-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Crush E, Arseneault L, Jaffee SR, Danese A, Fisher HL. Protective Factors for Psychotic Symptoms Among Poly-victimized Children. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44:691-700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Martínez I, Garcia F, Fuentes MC, Veiga F, Garcia OF, Rodrigues Y, Cruise E, Serra E. Researching Parental Socialization Styles across Three Cultural Contexts: Scale ESPA29 Bi-Dimensional Validity in Spain, Portugal, and Brazil. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kingston JL, Ellett L, Thompson EC, Gaudiano BA, Krkovic K. A Child-Parent Dyad Study on Adolescent Paranoia and the Influence of Adverse Life Events, Bullying, Parenting Stress, and Family Support. Schizophr Bull. 2023;49:1486-1493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | McIntyre JC, Wickham S, Barr B, Bentall RP. Social Identity and Psychosis: Associations and Psychological Mechanisms. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44:681-690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Schönig SN, Thompson E, Kingston J, Gaudiano BA, Ellett L, Krkovic K. The Apple Doesn't Fall Far from the Tree? Paranoia and Safety Behaviours in Adolescent-Parent-Dyads. Res Child Adolesc Psychopathol. 2024;52:267-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Benito A, Calvo G, Real-López M, Gallego MJ, Francés S, Turbi Á, Haro G. Creation of the TXP parenting questionnaire and study of its psychometric properties. Adicciones. 2019;31:117-135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Fonseca-Pedrero E, Inchausti F, Pérez-Albéniz A, Ortuño-Sierra J. Validation of the Prodromal Questionnaire-Brief in a representative sample of adolescents: Internal structure, norms, reliability, and links with psychopathology. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2018;27:e1740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Loewy RL, Pearson R, Vinogradov S, Bearden CE, Cannon TD. Psychosis risk screening with the Prodromal Questionnaire--brief version (PQ-B). Schizophr Res. 2011;129:42-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 362] [Cited by in RCA: 351] [Article Influence: 23.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Fonseca-Pedrero E, Ortuño-Sierra J, Chocarro E, Inchausti F, Debbané M, Bobes J. Psychosis risk screening: Validation of the youth psychosis at-risk questionnaire - brief in a community-derived sample of adolescents. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2017;26:e1543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Davidson JR, Book SW, Colket JT, Tupler LA, Roth S, David D, Hertzberg M, Mellman T, Beckham JC, Smith RD, Davison RM, Katz R, Feldman ME. Assessment of a new self-rating scale for post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychol Med. 1997;27:153-160. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 628] [Cited by in RCA: 643] [Article Influence: 22.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Oliver D, Arribas M, Radua J, Salazar de Pablo G, De Micheli A, Spada G, Mensi MM, Kotlicka-Antczak M, Borgatti R, Solmi M, Shin JI, Woods SW, Addington J, McGuire P, Fusar-Poli P. Prognostic accuracy and clinical utility of psychometric instruments for individuals at clinical high-risk of psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27:3670-3678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Consellería de Sanidade X de GEOP de la salud (OPS-O, Universidad CES C. Epidat: programa para análisis epidemiológico de datos. Versión 3.1. [cited 14 April 2025]. Available from: https://www.sergas.es/Saude-publica/epidat. |

| 33. | Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Censos de población y viviendas 2011. [cited 14 April 2025]. Available from: https://www.ine.es/jaxi/Tabla.htm?L=0&file=1mun12.px&path=/t20/e244/avance/p02/l0/. |

| 34. | Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. NY: Guilford Press, 2021. |

| 35. | Fonseca-Pedrero E, Gooding DC, Ortuño-Sierra J, Pflum M, Paino M, Muñiz J. Classifying risk status of non-clinical adolescents using psychometric indicators for psychosis spectrum disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2016;243:246-254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Hori H, Teraishi T, Sasayama D, Matsuo J, Kinoshita Y, Ota M, Hattori K, Kunugi H. A latent profile analysis of schizotypy, temperament and character in a nonclinical population: association with neurocognition. J Psychiatr Res. 2014;48:56-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Lång U, Yates K, Leacy FP, Clarke MC, McNicholas F, Cannon M, Kelleher I. Systematic Review and Meta-analysis: Psychosis Risk in Children and Adolescents With an At-Risk Mental State. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022;61:615-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Howie C, Potter C, Shannon C, Davidson G, Mulholland C. Screening for the at-risk mental state in educational settings: A systematic review. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2020;14:643-654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Zarubin VC, Gupta T, Mittal VA. History of trauma is a critical treatment target for individuals at clinical high-risk for psychosis. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:1102464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Müller N. Inflammation in Schizophrenia: Pathogenetic Aspects and Therapeutic Considerations. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44:973-982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 342] [Cited by in RCA: 456] [Article Influence: 57.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Vargas T, Lam PH, Azis M, Osborne KJ, Lieberman A, Mittal VA. Childhood Trauma and Neurocognition in Adults With Psychotic Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2019;45:1195-1208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Stoltenborgh M, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van Ijzendoorn MH. The neglect of child neglect: a meta-analytic review of the prevalence of neglect. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2013;48:345-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 456] [Cited by in RCA: 367] [Article Influence: 28.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Carvalho Silva R, Oliva F, Barlati S, Perusi G, Meattini M, Dashi E, Colombi N, Vaona A, Carletto S, Minelli A. Childhood neglect, the neglected trauma. A systematic review and meta-analysis of its prevalence in psychiatric disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2024;335:115881. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Stoltenborgh M, van Ijzendoorn MH, Euser EM, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ. A global perspective on child sexual abuse: meta-analysis of prevalence around the world. Child Maltreat. 2011;16:79-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1148] [Cited by in RCA: 1014] [Article Influence: 67.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Langeland W, Smit JH, Merckelbach H, de Vries G, Hoogendoorn AW, Draijer N. Inconsistent retrospective self-reports of childhood sexual abuse and their correlates in the general population. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2015;50:603-612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Guo X, Hao C, Wang W, Li Y. Parental Burnout, Negative Parenting Style, and Adolescents' Development. Behav Sci (Basel). 2024;14:161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Bowlby J. A secure base: parent-child attachment and Healthy Human Development. DC: American Psychological Association, 1988. |

| 48. | Coughlan H, Healy C, Ní Sheaghdha Á, Murray G, Humphries N, Clarke M, Cannon M. Early risk and protective factors and young adult outcomes in a longitudinal sample of young people with a history of psychotic-like experiences. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2020;14:307-320. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Chatziioannidis S, Andreou C, Agorastos A, Kaprinis S, Malliaris Y, Garyfallos G, Bozikas VP. The role of attachment anxiety in the relationship between childhood trauma and schizophrenia-spectrum psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 2019;276:223-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Newman-Taylor K, Kemp A, Potter H, Au-Yeung SK. An Online Investigation of Imagery to Attenuate Paranoia in College Students. J Child Fam Stud. 2018;27:853-859. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 51. | Pitfield C, Maguire T, Newman-Taylor K. Impact of attachment imagery on paranoia and mood: evidence from two single case studies. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2020;48:572-583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Catalan A, Angosto V, Díaz A, Valverde C, de Artaza MG, Sesma E, Maruottolo C, Galletero I, Bustamante S, Bilbao A, van Os J, Gonzalez-Torres MA. Relation between psychotic symptoms, parental care and childhood trauma in severe mental disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2017;251:78-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Ortega Gaite S, Shen M, Perales Montolio MJ. Mediación intercultural: clave en la formación inicial y desarrollo docente para educar en la sociedad diversa. Publicaciones. 2019;49:151-163. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 54. | Garcia F, Serra E, Garcia OF, Martinez I, Cruise E. A Third Emerging Stage for the Current Digital Society? Optimal Parenting Styles in Spain, the United States, Germany, and Brazil. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:2333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Orquin JL, Lahm ES, Stojić H. The visual environment and attention in decision making. Psychol Bull. 2021;147:597-617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Mahrer NE, Holly LE, Luecken LJ, Wolchik SA, Fabricius W. Parenting Style, Familism, and Youth Adjustment in Mexican American and European American Families. J Cross Cult Psychol. 2019;50:659-675. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Lorence B, Nunes C, Menéndez S, Pérez-Padilla J, Hidalgo V. Adolescent Perception of Maternal Practices in Portugal and Spain: Similarities and Differences. Sustainability. 2020;12:5910. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 58. | García-Mendoza MC, Parra A, Sánchez-Queija I, Oliveira JE, Coimbra S. Gender Differences in Perceived Family Involvement and Perceived Family Control during Emerging Adulthood: A Cross-Country Comparison in Southern Europe. J Child Fam Stud. 2022;31:1007-1018. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173-1182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1966] [Cited by in RCA: 2985] [Article Influence: 74.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Hayes AF, Rockwood NJ. Regression-based statistical mediation and moderation analysis in clinical research: Observations, recommendations, and implementation. Behav Res Ther. 2017;98:39-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 903] [Cited by in RCA: 1255] [Article Influence: 139.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Tofighi D, MacKinnon DP. RMediation: an R package for mediation analysis confidence intervals. Behav Res Methods. 2011;43:692-700. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1041] [Cited by in RCA: 889] [Article Influence: 59.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | JOHNSON PO, FAY LC. The Johnson-Neyman technique, its theory and application. Psychometrika. 1950;15:349-367. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 396] [Cited by in RCA: 413] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | McMahon EM, Corcoran P, Keeley H, Clarke M, Coughlan H, Wasserman D, Hoven CW, Carli V, Sarchiapone M, Healy C, Cannon M. Risk and protective factors for psychotic experiences in adolescence: a population-based study. Psychol Med. 2021;51:1220-1228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | DeVylder JE, Ryan TC, Cwik M, Wilson ME, Jay S, Nestadt PS, Goldstein M, Wilcox HC. Assessment of Selective and Universal Screening for Suicide Risk in a Pediatric Emergency Department. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e1914070. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Solmi M, Soardo L, Kaur S, Azis M, Cabras A, Censori M, Fausti L, Besana F, Salazar de Pablo G, Fusar-Poli P. Meta-analytic prevalence of comorbid mental disorders in individuals at clinical high risk of psychosis: the case for transdiagnostic assessment. Mol Psychiatry. 2023;28:2291-2300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Fonseca-Pedrero E, Gooding DC, Ortuño-Sierra J, Paino M. Assessing self-reported clinical high risk symptoms in community-derived adolescents: A psychometric evaluation of the Prodromal Questionnaire-Brief. Compr Psychiatry. 2016;66:201-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/