Published online Jul 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i7.106762

Revised: April 10, 2025

Accepted: May 6, 2025

Published online: July 19, 2025

Processing time: 124 Days and 21 Hours

Coronary heart disease (CHD) has shown a consistent upward trend in global incidence in recent years. Notably, older adults with CHD complicated by arrhy

To evaluate the efficacy of psychological care in reducing anxiety and depressive symptoms among older adult patients with CHD and comorbid arrhythmia.

This retrospective analysis included 100 patients with CHD and arrhythmia admitted to the First Affiliated Hospital of Jinzhou Medical University from June 2024 to December 2024. Of these, 49 patients in the control group received routine care, whereas 51 patients in the observation group received psychological care in addition to routine care. Therapeutic outcomes were compared between the two groups. Psychological distress was assessed before and after providing nursing care. A treatment compliance scale developed by the hospital was used to assess adherence. Complication rates were also compared. Quality of life was evaluated using the Short Form-36 Health Survey after providing nursing care. Patient satisfaction with nursing care was assessed using a self-designed questionnaire.

The observation group demonstrated a higher overall treatment effectiveness compared with the control group (P < 0.05). After nursing care, both groups showed reduced scores on the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale and Self-Rating Depression Scale compared with baseline (P < 0.05), with significantly greater improvements in the observation group (P < 0.05). Treatment compliance was higher and complication rates were lower in the observation group (P < 0.05). Additionally, the observation group demonstrated better quality of life after 1 month of care and higher satisfaction with nursing services (P < 0.05).

Psychological care for patients with CHD and comorbid arrhythmia effectively enhanced therapeutic outcomes, reduced anxiety and depression, improved treatment compliance and quality of life, and lowered the risk of complications. These findings support the broader implementation of psychological care for patients with CHD in clinical practice.

Core Tip: Psychological care interventions have led to statistically significant improvements in both emotional distress and treatment compliance among older adult patients with coronary heart disease. These interventions are associated with clinically meaningful reductions in depressive and anxiety symptoms while enhancing treatment adherence and overall care. The implementation of structured psychological care protocols provides substantial long-term benefits for this patient population. Our findings indicate that such interventions are linked to a measurable reduction in cardiovascular event rates and significant improvements across multiple quality-of-life domains, including physical functioning, social functioning, and both emotional and physical role performance.

- Citation: Yang S, Gao XM, Li SJ, Yang X. Influence of psychological care on anxiety and depression in older adult patients with coronary heart disease complicated by arrhythmia. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(7): 106762

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i7/106762.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i7.106762

Coronary heart disease (CHD), also known as ischemic heart disease, is a common cardiovascular disorder that primarily affects older adults, with a steadily increasing incidence in recent years[1]. The underlying pathophysiology involves the accumulation of atherosclerotic plaques within the coronary arteries, leading to luminal narrowing, vascular obstruction, and spasms. These changes cause myocardial ischemia and hypoxia, which may progress to tissue necrosis[2].

Arrhythmia is a common condition and complication in patients with CHD, primarily caused by CHD-induced abnormalities in rhythm and pulse conduction at the onset of cardiac activity. The presence of arrhythmia in CHD indicates severe myocardial ischemia, which significantly increases the risk of acute myocardial infarction, cardiogenic shock, and sudden death[3,4]. Therefore, timely and effective treatment should be administered to patients with CHD complicated by arrhythmia.

Compared with the general patient population, older adult patients with CHD complicated by arrhythmia are more likely to experience negative emotions such as anxiety, depression, and fear. These emotions often manifest as treatment noncompliance, persistent low mood, and a lack of trust in medical care and treatment[4,5]. Therefore, to improve prognosis, nursing care during treatment should be enhanced to alleviate both psychological and physiological discomfort and to improve patient adherence to treatment and nursing protocols[6].

The professional psychological care model is a holistic, interdisciplinary, and phased approach to psychological nursing, tailored to each patient’s specific condition. It helps patients adjust their psychological state and mitigate the impact of negative emotions on their illness through the appropriate application of individual and group psychotherapies[7]. Psychological care interventions reduce anxiety and depression in patients with CHD[8]. However, the interaction between psychological and physiological factors is complex[9], and the effects of psychological interventions on alleviating anxiety and depression in patients with CHD remain unclear. Furthermore, a comprehensive analysis of the role of psychological care in older adult patients with CHD complicated by arrhythmia is currently lacking. This study aimed to systematically evaluate the therapeutic benefits of a structured psychological care protocol for reducing anxiety and depressive symptoms in this high-risk population.

This retrospective cohort study analyzed clinical data from 100 consecutive patients diagnosed with CHD and comorbid arrhythmia who were admitted between June and December 2024. Participants were categorized into a control group (n = 49), which received conventional care protocols, and an observation group (n = 51), which received supplemental psychological care interventions in addition to conventional treatment. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients who met the diagnostic criteria for CHD complicated by arrhythmia[10]; (2) Age > 60 years; and (3) Availability of complete medical records. We excluded patients with (1) Malignant tumors; (2) Other serious organ diseases; or (3) Severe coagulation disorders.

Patients in the control group received routine care, which primarily included monitoring of vital signs after admission, communicating with patients about their treatment, and providing guidance on diet and medication. Patients in the observation group received routine care combined with psychological care interventions as follows: (1) Nursing staff assessed each patient’s condition, education level, living habits, and other relevant factors to develop tailored psychological care plans. They actively established a positive nurse–patient relationship, communicated with patients to gain their trust, and listened attentively to patient concerns to understand their psychological needs. Nurses also monitored emotional and psychological changes for timely counseling. The pathogenesis, treatment, and prognosis of CHD were explained to help patients develop a correct understanding of their condition. To improve confidence and treatment compliance, patients were reassured that arrhythmia is manageable and could be effectively controlled through timely treatment. Additionally, patients were informed that negative emotions may increase cardiac workload and reduce treatment efficacy; (2) Anxiety and depression were regularly assessed to monitor each patient’s psychological state. Nurses identified the triggers of adverse emotions and provided timely psychological counseling. Patients underwent cognitive behavioral therapy combined with mindfulness training twice a week, with each session lasting 60 minutes. Communication with patients was further enhanced to help them maintain a positive outlook and understand the beneficial role of optimism in recovery; (3) Medical staff performed daily disinfection, window ventilation, and waste disposal to ensure a clean, hygienic, and safe ward environment; (4) To prevent excessive intake of high-sugar and high-calorie foods, nurses assessed patients’ dietary preferences and developed personalized nutrition plans. Patients also received appropriate vitamin supplementation; and (5) Based on physicians’ instructions, nurses provided medication guidance, ensuring that patients took medications on time and at the correct dose. Medication doses were adjusted appropriately according to the patient’s condition. Patients were instructed not to alter the dosage or discontinue medication without medical supervision and were encouraged to promptly report any adverse reactions. They were also advised to maintain adequate sleep and rest. The treatment duration for all patients was 1 month.

Primary outcome measures: (1) Therapeutic effectiveness was assessed and categorized as marked effectiveness [complete resolution of clinical symptoms and normal electrocardiograph (ECG) findings], effectiveness (alleviation of clinical symptoms and improved ECG findings), or ineffectiveness (no improvement in clinical symptoms or ECG findings). The total effective rate was calculated using the formula: (markedly effective cases + effective cases)/total number of cases × 100%; (2) Psychological distress was evaluated before and after nursing care using the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS)[11]; and (3) A treatment compliance scale developed by the hospital was used to assess adherence to treatment and nursing care. Based on a 100-point scale, scores < 60 indicated noncompliance, 60-90 indicated partial compliance, and > 90 indicated complete compliance. The total compliance rate was calculated as follows: (partial compliance cases + complete compliance cases)/total number of cases × 100%.

Measures: (1) Complications during hospitalization, including heart failure, myocardial infarction, and death, were recorded and compared between groups; (2) Quality of life was assessed using the validated Short Form-36 Health Survey[12], covering domains such as physical functioning, social functioning, and emotional and physical role performance. Higher scores indicated better quality of life; and (3) Patient satisfaction with nursing care was assessed using a questionnaire with three response categories: very satisfied, satisfied, and dissatisfied.

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 20.0 (Beijing ND Times Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD, and between-group and within-group comparisons (before and after providing nursing care) were conducted using the independent samples t-test and paired t-test, respectively. The χ2 test was used to analyze categorical data. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

No statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups in terms of sex, age, body mass index, or other general characteristics (P > 0.05), indicating comparability (Table 1).

| Factors | Observation group (n = 51) | Control group (n = 49) | χ2 | P value |

| Sex | 0.141 | 0.707 | ||

| Male | 30 (58.82) | 27 (55.10) | ||

| Female | 21 (41.18) | 22 (44.90) | ||

| Age (years) | 0.051 | 0.822 | ||

| ≤ 65 | 23 (45.10) | 21 (42.86) | ||

| > 65 | 28 (54.90) | 28 (57.14) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 0.001 | 0.997 | ||

| ≤ 23 | 26 (50.98) | 25 (51.02) | ||

| > 23 | 25 (49.02) | 24 (48.98) | ||

| Smoking history | 0.123 | 0.726 | ||

| With | 36 (70.59) | 33 (67.35) | ||

| Without | 15 (29.41) | 16 (32.65) | ||

| Educational level | 0.157 | 0.692 | ||

| Below junior high school | 27 (52.94) | 24 (48.98) | ||

| Junior high school or above | 24 (47.06) | 25 (51.02) | ||

| Drinking history | 0.055 | 0.814 | ||

| With | 22 (43.14) | 20 (40.82) | ||

| Without | 29 (56.86) | 29 (59.18) | ||

Therapeutic effectiveness after nursing care was compared between groups. In the observation group, 35 cases were markedly effective, 13 were effective, and 3 were ineffective, resulting in a total effective rate of 94.12%. In the control group, 26, 12, and 11 cases were recorded in the same respective categories, yielding a total effective rate of 77.55%. Comparative analysis indicated superior therapeutic effectiveness in the observation group (P < 0.05) (Table 2).

| Groups | Observation group (n = 51) | Control group (n = 49) | χ2 | P value |

| Marked effectiveness | 35 (68.63) | 26 (53.06) | - | - |

| Effectiveness | 13 (25.49) | 12 (24.49) | - | - |

| Ineffectiveness | 3 (5.88) | 11 (22.45) | - | - |

| Total effective rate | 48 (94.12) | 38 (77.55) | 5.696 | 0.017 |

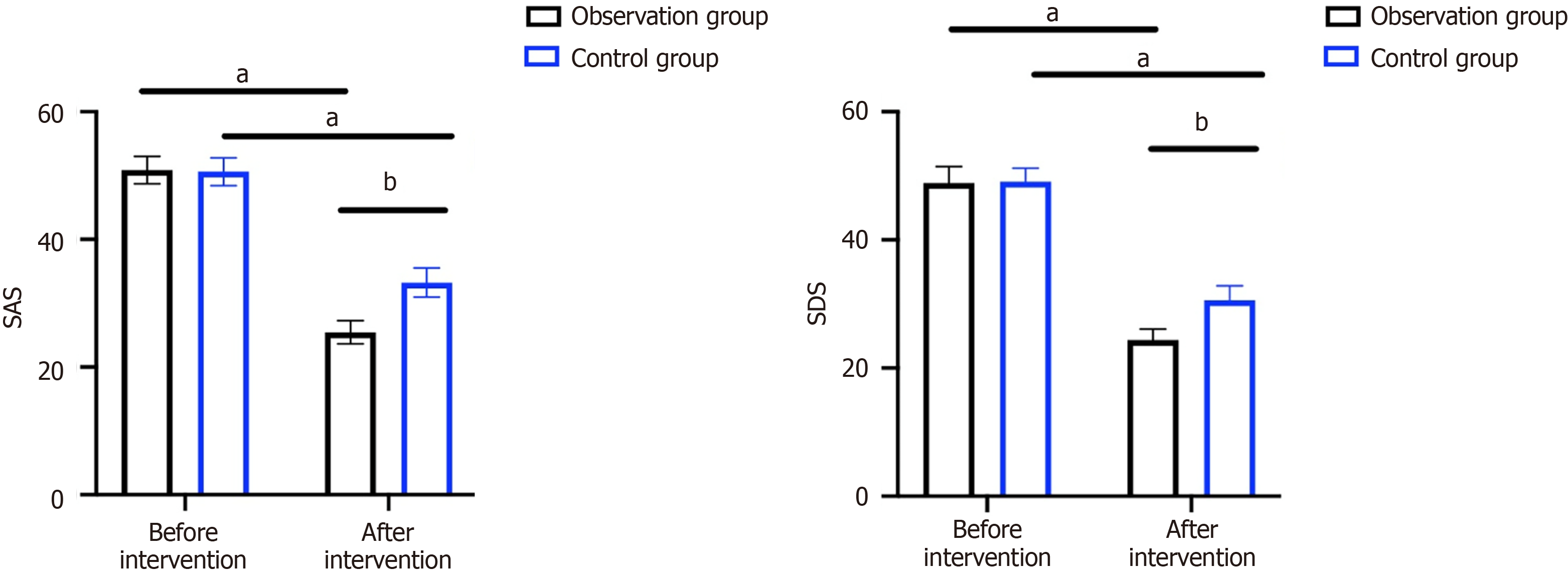

Standardized evaluation using the SAS and SDS revealed comparable baseline scores between groups (P > 0.05). After nursing care, both groups showed significant reductions in SAS and SDS scores, indicating alleviated negative emotions, with more pronounced improvements in the observation group (P < 0.05) (Figure 1).

Treatment compliance was recorded and compared after nursing care. In the observation group, 31 patients were completely compliant, 19 were partially compliant, and 1 was noncompliant, resulting in a compliance rate of 98.04%. In the control group, 20, 19, and 10 patients were categorized into the respective categories, with a compliance rate of 79.59%. These results indicate higher treatment compliance in the observation group (Table 3).

| Groups | Observation group (n = 51) | Control group (n = 49) | χ2 | P value |

| Complete compliance | 31 (60.78) | 20 (40.82) | - | - |

| Partial compliance | 19 (37.25) | 19 (38.78) | - | - |

| Noncompliance | 1 (1.96) | 10 (20.41) | - | - |

| Total compliance rate | 50 (98.04) | 39 (79.59) | 8.687 | 0.003 |

In the observation group, complications included heart failure in one patient and myocardial infarction in one patient, with no reported deaths, yielding an overall complication rate of 5.88%. In contrast, the control group had three patients with heart failure, five with myocardial infarction, and two deaths, resulting in a complication rate of 20.41%. The complication rate was significantly lower in the observation group than in the control group (P < 0.05) (Table 4).

| Complications | Observation group (n = 51) | Control group (n = 49) | χ2 | P value |

| Heart failure | 1 (1.96) | 3 (6.12) | - | - |

| Myocardial infarction | 2 (3.92) | 5 (10.20) | - | - |

| Death | 0 | 2 (4.08) | - | - |

| Total | 3 (5.88) | 10 (20.41) | 4.662 | 0.031 |

Assessment using the Short Form 36-Item Health Survey revealed significantly higher scores in physical functioning, social functioning, and emotional and physical role domains in the observation group compared with the control group, indicating a better quality of life in the observation group (P < 0.05) (Table 5).

| Project | Observation group (n = 51) | Control group (n = 49) | t | P value |

| Physical functioning | 15.39 ± 1.1 | 11.12 ± 1.15 | 18.98 | < 0.001 |

| Social functioning | 16.18 ± 1.18 | 12.04 ± 1.17 | 17.61 | < 0.001 |

| Role-emotional | 16.24 ± 1.12 | 12.24 ± 0.99 | 18.89 | < 0.001 |

| Role-physical | 13.76 ± 1.12 | 10.18 ± 1.03 | 16.62 | < 0.001 |

In the observation group, 40 patients were very satisfied, 10 were satisfied, and 1 was dissatisfied, resulting in a nursing satisfaction rate of 98.04%. In the control group, 23 were very satisfied, 14 were satisfied, and 12 were dissatisfied, with a satisfaction rate of 75.51%. Nursing satisfaction was significantly higher in the observation group than in the control group (P < 0.05) (Table 6).

| Groups | Observation group (n = 51) | Control group (n = 49) | χ2 | P value |

| Very satisfied | 40 (78.43) | 23 (46.94) | - | - |

| Satisfied | 10 (19.61) | 14 (28.57) | - | - |

| Dissatisfied | 1 (1.96) | 12 (24.49) | - | - |

| Nursing satisfaction | 50 (98.04) | 37 (75.51) | 11.21 | < 0.001 |

As a common cardiovascular disease, CHD has become one of the major health threats worldwide[13]. Coronary atherosclerosis in patients with CHD leads to partial or complete occlusion of the coronary arteries, resulting in atrial fibrillation and arrhythmia, as well as hypoxic and ischemic necrosis of cardiomyocytes[14]. Epidemiological studies have shown that approximately 75% of patients with CHD develop arrhythmia[15]. Notably, due to the need for long-term treatment and the recurrent nature of the disease, patients with CHD are psychologically vulnerable and prone to developing negative emotions[16]. More than 80% of older adult patients with CHD and comorbid arrhythmia exhibit significant psychological disturbances, primarily anxiety and depression. These symptoms are often manifested as social withdrawal, low mood, crying spells, frustration, and noncompliance with treatment[17]. Consequently, there is increasing clinical interest in implementing psychological interventions for this patient population to enhance treatment outcomes and improve overall efficacy.

Psychological care, an emerging nursing modality grounded in evidence-based medicine, offers more scientific, effective, and targeted support tailored to a patient’s condition and physical status[18]. Our findings revealed that patients in the observation group who received psychological care showed more significant improvements in clinical symptoms and ECG results compared with those receiving routine care. This suggests that the implementation of psychological care contributes to improved therapeutic outcomes. Patients with CHD complicated by arrhythmia experience not only a range of physical symptoms but also considerable psychological distress. This is especially pronounced in older adults, who often experience anxiety, fear, and depression due to diminished physical function, uncertainty about their prognosis, limited social support, absence of family companionship, and concerns about treatment costs[19]. In our study, both groups exhibited significant reductions in anxiety and depression scores after nursing care; however, the improvements were more pronounced in the observation group. Furthermore, patients in the observation group demonstrated higher compliance with follow-up treatment and care. This outcome can be attributed to the comprehensive measures provided through psychological care, particularly the explanation of CHD and arrhythmia-related knowledge and emotional counseling, which helped alleviate negative emotions and enhance adherence. In contrast, the conventional care model - primarily limited to basic daily interactions - lacked structured psychological assessment or intervention. This shortfall in emotional support may lead to a worsening of negative emotional states, ultimately impairing treatment outcomes. Supporting our findings, previous evidence has highlighted that effective nursing interventions can enhance therapeutic efficacy by alleviating psychological distress and increasing treatment cooperation[20].

Furthermore, statistical analysis of complications revealed a lower complication rate in the observation group. A comprehensive understanding and prediction of the patient’s condition during psychological care facilitated more accurate monitoring and assessment, thereby enhancing treatment compliance and reducing the risk of complications[21]. We also evaluated patients’ quality of life after discharge. As expected, the observation group demonstrated significantly better quality of life compared to the control group, suggesting that psychological care not only alleviates negative emotions and improves therapeutic outcomes but also enhances overall well-being. This finding aligns with those of a previous study, which reported significant improvements in quality of life among patients with CHD following long-term psychological care[22]. Conversely, patients receiving routine care exhibited substantial psychological comorbidities that remained unaddressed throughout the treatment process. This unmanaged emotional distress—characterized by persistent disease-related anxiety and maladaptive fear responses—was associated with poor treatment adherence, which in turn increased the risk of disease progression and complications. Lastly, nursing care satisfaction was significantly higher in the observation group than in the control group. Our study consistently follows a patient-centered nursing philosophy, emphasizing comprehensive, individualized care, which contributes to reduced nursing-related disputes and improved patient satisfaction.

The application of psychological care in patients with CHD complicated by arrhythmia is effective in enhancing therapeutic outcomes, alleviating depression and anxiety, increasing treatment compliance, reducing complication rates, and improving quality of life. These findings support the broader adoption of psychological care in clinical practice.

However, this study has some limitations. First, the relatively small sample size may limit the generalizability of the results, warranting further validation through multicenter, large-scale studies. Second, the retrospective study design introduces potential methodological biases, including selection bias, information bias, and residual confounding from unmeasured variables. Additionally, deviations in the implementation of psychological care interventions may have occurred. To address these limitations, we plan to conduct prospective randomized controlled trials in future research to further validate our findings.

| 1. | Khamis RY, Ammari T, Mikhail GW. Gender differences in coronary heart disease. Heart. 2016;102:1142-1149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 123] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tian Y, Deng P, Li B, Wang J, Li J, Huang Y, Zheng Y. Treatment models of cardiac rehabilitation in patients with coronary heart disease and related factors affecting patient compliance. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2019;20:27-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dong Y, Chen H, Gao J, Liu Y, Li J, Wang J. Molecular machinery and interplay of apoptosis and autophagy in coronary heart disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2019;136:27-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 323] [Article Influence: 46.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Muscella A, Stefàno E, Marsigliante S. The effects of exercise training on lipid metabolism and coronary heart disease. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2020;319:H76-H88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Richards SH, Anderson L, Jenkinson CE, Whalley B, Rees K, Davies P, Bennett P, Liu Z, West R, Thompson DR, Taylor RS. Psychological interventions for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD002902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Richards SH, Anderson L, Jenkinson CE, Whalley B, Rees K, Davies P, Bennett P, Liu Z, West R, Thompson DR, Taylor RS. Psychological interventions for coronary heart disease: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2018;25:247-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Godfrey KM, Reynolds RM, Prescott SL, Nyirenda M, Jaddoe VW, Eriksson JG, Broekman BF. Influence of maternal obesity on the long-term health of offspring. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5:53-64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 533] [Cited by in RCA: 741] [Article Influence: 82.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Valiee S, Razavi NS, Aghajani M, Bashiri Z. Effectiveness of a psychoeducation program on the quality of life in patients with coronary heart disease: A clinical trial. Appl Nurs Res. 2017;33:36-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zhang Y, Liang Y, Huang H, Xu Y. Systematic review and meta-analysis of psychological intervention on patients with coronary heart disease. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10:8848-8857. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Qin T, Sheng W, Hu G. To Analyze the Influencing Factors of Senile Coronary Heart Disease Patients Complicated with Frailty Syndrome. J Healthc Eng. 2022;2022:7619438. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Fu M, Wang Z, Liu Y. Effects of Xinkeshu combined with levosimendan on perioperative heart failure in oldest-old patients with hip fractures. J Tradit Chin Med. 2020;40:870-874. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Shayan NA, Arslan UE, Hooshmand AM, Arshad MZ, Ozcebe H. The Short Form Health Survey (SF-36): translation and validation study in Afghanistan. East Mediterr Health J. 2020;26:899-908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Orth-Gomér K. Behavioral interventions for coronary heart disease patients. Biopsychosoc Med. 2012;6:5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Oancea AF, Morariu PC, Buburuz AM, Miftode IL, Miftode RS, Mitu O, Jigoranu A, Floria DE, Timpau A, Vata A, Plesca C, Botnariu G, Burlacu A, Scripcariu DV, Raluca M, Cuciureanu M, Tanase DM, Costache-Enache II, Floria M. Spectrum of Non-Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease and Its Relationship with Atrial Fibrillation. J Clin Med. 2024;13:4921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Strodl E, Kenardy J. A history of heart interventions moderates the relationship between psychological variables and the presence of chest pain in older women with self-reported coronary heart disease. Br J Health Psychol. 2013;18:687-706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chan IWS, Lai JCL, Wong KWN. Resilience is associated with better recovery in Chinese people diagnosed with coronary heart disease. Psychol Health. 2006;21:335-349. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ladwig KH, Goette A, Atasoy S, Johar H. Psychological aspects of atrial fibrillation: A systematic narrative review : Impact on incidence, cognition, prognosis, and symptom perception. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2020;22:137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Zambrano J, Celano CM, Januzzi JL, Massey CN, Chung WJ, Millstein RA, Huffman JC. Psychiatric and Psychological Interventions for Depression in Patients With Heart Disease: A Scoping Review. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e018686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Oranta O, Luutonen S, Salokangas RK, Vahlberg T, Leino-Kilpi H. The outcomes of interpersonal counselling on depressive symptoms and distress after myocardial infarction. Nord J Psychiatry. 2010;64:78-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bouchard V, Robitaille A, Perreault S, Cyr MC, Tardif JC, Busseuil D, D'Antono B. Psychological distress, social support, and use of outpatient care among adult men and women with coronary artery disease or other non-cardiovascular chronic disease. J Psychosom Res. 2023;165:111131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Nekouei ZK, Yousefy A, Doost HT, Manshaee G, Sadeghei M. Structural Model of psychological risk and protective factors affecting on quality of life in patients with coronary heart disease: A psychocardiology model. J Res Med Sci. 2014;19:90-98. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Ladwig KH, Lurz J, Lukaschek K. [Long-term course of heart disease: How can psychosocial care be improved?]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2022;65:481-487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/