Published online Jul 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i7.104373

Revised: May 13, 2025

Accepted: May 22, 2025

Published online: July 19, 2025

Processing time: 92 Days and 19 Hours

Depression is a common mental disorder among adolescents, characterized by a high rate of suicide and self-harm, which not only is devastating to families but also has a negative impact on society. Psychological factors such as impulsive personality, perceived chronic social adversity (PCSA), and sense of security are closely associated with suicide risk in adolescents with depression. Few studies have been conducted on the relationship between these factors.

To explore the impact of impulsive personality on suicide risk in adolescents with depression and the chain mediating effect between PCSA and sense of security.

This study is a retrospective study. A total of 200 adolescents with depression who visited the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region Maternal and Child Health Hospital from January 2021 to December 2023 comprised the study cohort. The PCSA scale, Security Questionnaire, Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, and Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation were used to evaluate depression.

Suicide risk was positively correlated with impulsive personality and PCSA (P < 0.05), whereas sense of security was negatively correlated with suicide risk, impulsive personality, and PCSA (P < 0.05). The total indirect effect of PCSA and sense of security on impulsive personality and suicide risk was 35.43%, with the mediating effect of PCSA and sense of security contributing 16.53% and 15.75%, respectively. PCSA and sense of security exhibited a chain mediating effect between impulsive personality and suicide risk, accounting for 3.15%.

The suicide risk of adolescents with depression is significantly associated with impulsive personality, PCSA, and sense of security. Impulsive personality affects the suicide risk of adolescents with depression both directly and indirectly, with the latter occurring via PCSA and sense of security.

Core Tip: This study focuses on adolescent patients with depression and examines the relationship between impulsive personality, perceived chronic social adversity (PCSA), sense of security, and suicide risk. An analysis of 200 adolescent patients with depression revealed that their suicide risk was positively correlated with impulsive personality and PCSA and negatively correlated with sense of security. PCSA and sense of security play a chain mediating role between impulsive personality and suicide risk. Reducing the level of PCSA and enhancing the sense of security among adolescents with depression may reduce their suicide risk.

- Citation: Zhang H, Li HB, Sun FS, Su XQ, Sun CB. Effects of impulsive personality on suicide in adolescent depression: The chain mediating of perceived social adversity and security. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(7): 104373

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i7/104373.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i7.104373

Depression is a common mental disorder in adolescents. Studies have shown that 37% of adolescents have depression, which is the primary risk factor for adolescent suicide[1]. Approximately 17.6%-23.5% of adolescents have seriously considered ending their lives, and adolescent suicide is closely associated with depression[2]. The adverse social and family consequences of adolescent suicide are a growing public health problem. Studies have found that suicidal ideation, which is the first step of suicide, is key to suicide prevention[3]. Among the many factors influencing the suicide risk of adolescent patients with depression, impulsive personality, perceived chronic social adversity (PCSA), and sense of security have attracted significant attention[4]. Impulsive personality is the psychological tendency to respond quickly and unplanned to internal and external stimuli; this often results in adverse effects due to a lack of consideration of the consequences of such behavior. Carballo et al[5] found that impulsive personality markedly increases the risk of suicidal behavior. PCSA, also known as social trauma, refers to an individual’s subjective perception of persistent or recurring negative social events (such as rejection, rejection, and excessive control) in daily life[6]. PCSA causes individuals to lose control of their current state, resulting in confusion, anxiety, and even aggressive behavior. PCSA is reported to be one of the main risk factors for depression, and the more negative events an individual experiences, the greater the possibility of a psychological crisis[7]. According to the stimulus–cognitive–emotion model, an individual’s perception of negative events is a key factor that leads to the occurrence of negative emotions[8]. When PCSA reaches the limit of an individual’s negative cognitive load, depression and suicidal thoughts may arise. Security is the premonition of risk, and it involves a sense of control and certainty when dealing with threats. Several studies have reported that the level of psychological security, which has a negative predictive effect on suicidal ideation, is low among adolescents with depression[9,10]. Most existing studies have examined the relationship between a single factor and the suicide risk among adolescent patients with depression, while there is a lack of research on the interaction among multiple factors. Although some studies involved mediating variables, most have only examined the role of one mediating variable, and there are rela

A total of 200 adolescents with depression who visited the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region Maternal and Child Health Hospital from January 2021 to December 2023 were selected for the study. The inclusion criteria were as follows: The participants must: (1) Meet the diagnostic criteria for depression[11]; (2) Be aged 12-18 years; and (3) Score > 17 on the Hamilton Depression Scale-24. Patients were excluded if they had: (1) Other psychiatric disorders; (2) Other serious conditions including organ lesions and malignant tumors; (3) Participated in other psychological intervention studies; or (4) Exhibited mental retardation or vision, hearing, or speech impairment.

PCSA questionnaire: The PCSA scale established by Zhang et al[12] was used in this study. Scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree) with a total score of 140, the PCSA scale contains 28 items in 3 dimen

Security questionnaire: This questionnaire, compiled by Cong and An[13], consists of two dimensions of interpersonal security and a definite sense of control, with 8 entries each. This study used a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “very inconsistent” to “very consistent”, with a total score of 16-80 points; the higher the score, the higher the sense of security. Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.840. This questionnaire comprehensively assesses the level of security of adolescent patients with depression based on two aspects: Interpersonal communication and the sense of control over the environ

Barratt impulsiveness scale: This scale was validated by Lau et al[14], and it includes 3 dimensions impulsiveness, namely, cognitive, motor, and unplanned, with 10 items each. Scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “not”; 5 = “always”), the assessment yields a total score ranging from 30 to 150 points, with higher scores indicating stronger impulsivity. Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.80. This scale has high reliability and validity and can accurately assess the impulsivity of an individual in different dimensions, thereby providing a reliable basis for studying the relationship between impulsive personality and suicide risk.

Beck scale for suicide ideation: This scale was validated by Kliem et al[15], and it includes 2 dimensions of suicidal ideation (5 items) and suicidal tendency (14 items), with a total of 19 items. The scale is graded at 3 levels (0 = “no”, 1 = “medium”, and 2 = “strong”), with a total score of 0-38 points. The higher the score, the stronger the suicidal ideation and the higher the suicide risk. Cronbach’s α coefficient for this scale was 0.860. This scale is a classic tool for assessing suicide risk. It can measure the tendency for suicidal ideation among adolescent patients with depression relatively accurately, thus providing an effective assessment method for studying suicide risk.

After obtaining informed consent from the participants, the research team followed standardized guidelines to explain the contents of the questionnaire to the patients in detail and instructed them to give answers that closely align with their current situation. The questionnaire was filled out on the spot for review; therefore, any problems could be identified in time to fill the gaps.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 23.0 software. Measurement data were expressed as the mean ± SD and were compared between groups using a t-test. Count data use cases (%) were expressed, and a χ2 test was used for comparison. The Harman single-factor test and Pearson correlations were used for the common method deviation test and correlation analyses, respectively. The SPSS-process macro was used for mediating effect analysis. The significance value was set at P < 0.05.

A total of 210 questionnaires were sent out, of which 10 were inconsistent and 200 were valid, with an effective recovery rate of 95.24%. A total of 200 patients were included in this study, of whom 48.00% were female and 52.00% were male. Junior (aged 12-15 years) and senior (aged 15-18 years) high school students accounted for 38.00% and 62.00% of the sample, respectively. Other demographic variables are shown in Table 1.

| Variables | Categories | n | Proportion (%) |

| Gender | Female | 96 | 48.00 |

| Male | 104 | 52.00 | |

| Age (years) | 12-15 | 76 | 38.00 |

| 15-18 | 124 | 62.00 | |

| Grade level | Junior high school | 76 | 38.00 |

| Senior high school | 124 | 62.00 | |

| Only child | No | 98 | 49.00 |

| Yes | 102 | 51.00 | |

| Monthly household income (yuan) | < 2000 | 55 | 27.50 |

| 2000-5000 | 76 | 38.00 | |

| > 5000 | 69 | 19.50 | |

| Family history of depression | No | 155 | 77.50 |

| Yes | 45 | 22.50 | |

| Parental marital status | At marriage | 101 | 50.50 |

| Divorced/widowed | 99 | 49.50 |

Common method bias was tested using the Harman single-factor test. The results indicated that five of the unrotated eigenroots had factors > 1. The first factor accounted for 28.44% of the variation, falling below the critical threshold of 40%. Therefore, the data in this study do not show a significant common methodological bias.

There was no significant effect of demographic variables on the difference between the scores on each scale. As shown in Table 2, an independent sample t-test was conducted on gender for the dimensions of suicide risk, impulsive personality, sense of security, and PCSA. No significant difference was observed in the above variables between the students of different genders (P > 0.05), suggesting that gender factors do not influence these psychological dimensions.

| Variables | Male | Female | t | P value |

| Suicidal ideation | 6.81 ± 0.64 | 6.79 ± 0.71 | 0.168 | 0.867 |

| Suicidal tendency | 18.06 ± 3.28 | 17.89 ± 2.94 | 0.390 | 0.697 |

| Suicide risk | 24.87 ± 3.39 | 24.68 ± 3.06 | 0.412 | 0.681 |

| Cognitive impulse | 35.48 ± 3.74 | 35.82 ± 3.39 | 0.677 | 0.499 |

| Motor impulsivity | 31.76 ± 3.00 | 31.51 ± 3.37 | 0.553 | 0.581 |

| Unplanned impulsivity | 39.98 ± 3.84 | 40.24 ± 4.26 | 0.451 | 0.652 |

| Impulsive personality | 107.22 ± 5.93 | 107.57 ± 6.2 | 0.409 | 0.683 |

| Interpersonal security | 22.54 ± 3.82 | 22.99 ± 3.44 | 0.875 | 0.382 |

| Definite sense of control | 17.53 ± 3.29 | 17.90 ± 3.10 | 0.810 | 0.419 |

| Sense of security | 40.08 ± 4.49 | 40.89 ± 4.60 | 1.257 | 0.210 |

| PCSA | 59.06 ± 6.54 | 58.27 ± 5.84 | 0.894 | 0.372 |

Among the 200 patients, the suicide risk score was 24.78 ± 3.23, the impulsive personality score was 107.396.06, the PCSA score was 58.68 ± 6.22, and the safety score was 40.46 ± 4.55. Correlation analysis revealed suicide risk to be positively correlated with impulsive personality and PCSA (P < 0.05), while security to be negatively correlated with suicide risk, impulsive personality, and PCSA (P < 0.05) (Table 3).

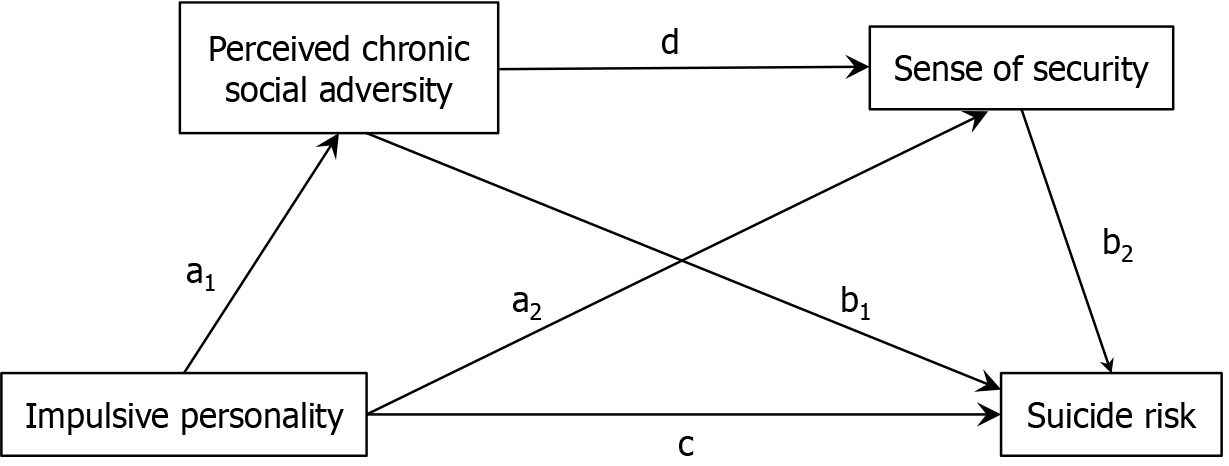

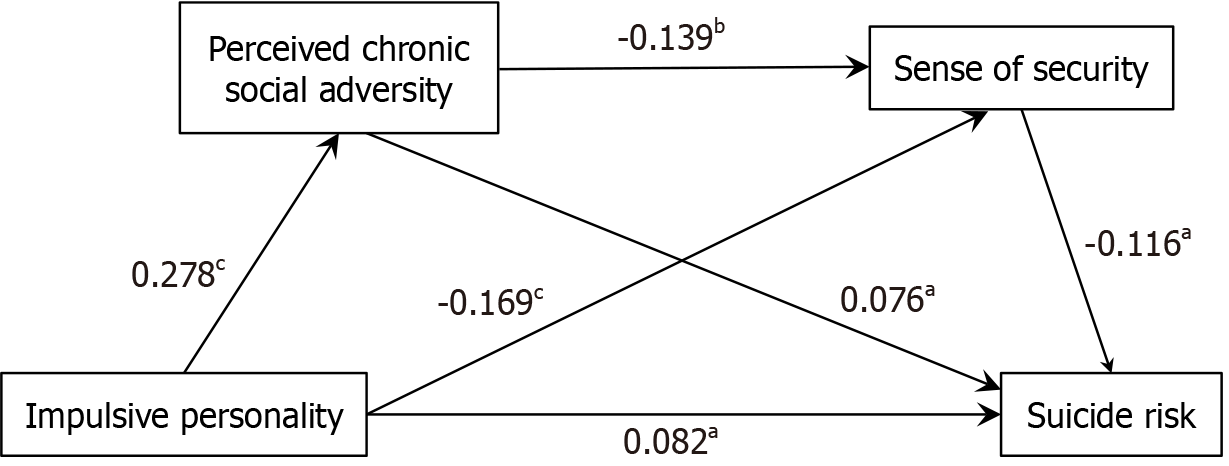

With impulsive personality as the independent variable, suicide risk as the dependent variable, and PCSA and sense of security as the mediating variables, the mediating effects of security and PCSA on the relationship between impulsive personality and suicide risk were evaluated using the SPSS-PROCESS macro (Figure 2 for the model). The results indicated that impulsive personality positively predicted PCSA and suicide risk and negatively predicted security. PCSA positively predicted suicide risk and negatively predicted security, while security negatively predicted suicide risk (Table 4). Using the Bootstrap program, 5000 repeated data samplings were used to test the mediating effect. PCSA and sense of security did not contain 0 in the 95% confidence interval of impulsive personality and suicide risk, indicating that the mediating effect was significant. For the analysis of the chain mediation effect between PCSA and sense of security, 95% confidence intervals do not include 0, indicating that the chain mediation effect is significant; the indirect effect size is 0.004, accounting for 3.15% of the effect (Table 5).

| Variables | Effect size | SE | 95%CI | Effect ratio (%) |

| Total effect | 0.127 | 0.037 | 0.055-0.200 | - |

| Direct effect | 0.082 | 0.038 | 0.007-0.157 | 64.57 |

| Total indirect effect | 0.045 | 0.018 | 0.015-0.082 | 35.43 |

| Impulsive personality→PCSA→suicide risk | 0.021 | 0.013 | 0.001-0.050 | 16.53 |

| Impulsive personality→sense of security→suicide risk | 0.020 | 0.011 | 0.002-0.045 | 15.75 |

| Impulsive personality→PCSA→sense of security→suicide risk | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.001-0.013 | 3.15 |

Depression is primarily characterized by low mood, anhedonia, as well as high suicide and self-harm rates[16]. Ado

In this study, the PCSA score of adolescents with depression was 58.68 ± 6.22, which was at a medium level, but higher than those reported by Yu and Zhao[18] in his study on college students. Interpersonal communication, academic pressure, and emotional pressure are major stressors for adolescents with depression[19], resulting in their perception of a psychological burden. Negative events such as academic failure, peer alienation or rejection, and constraints from others lead to a strong sense of alienation, frustration, and helplessness in adolescents with depression, thus increasing their suicidal risk. Furthermore, lack of security affects the adolescents’ ability to adapt to their environment and increases the likelihood of adopting negative coping strategies such as avoidance and withdrawal[20]. In this study, the sense of security scores of adolescents with depression (40.46 ± 4.55) was at a medium level, which was consistent with those reported by Niu et al[21]. First, social dysfunction is the main reason for the decreased sense of security in adole

PCSA showed a 16.53% mediating effect between impulsive personality and suicide risk. Impulsive personality traits include being impatient, unwilling to take the time for thoughtful and detailed analyses, and thrill seeking for instant gratification. This leads to poor executive function, difficulty in focusing on processing information and making rational decisions, and continuous and passive immersion in negative emotional states, which further increases PCSA. As adolescents with depression feel intense despair when immersed in negative emotions, they struggle to overcome any predicament or change their views and negative emotions, thus increasing suicidal ideation. Jankowski et al[22] observed that impulsive personality significantly increases the risk of suicide, which is closely associated with PCSA. Moreover, according to the interpersonal theory of suicide, suicidal ideation turns into suicidal behavior when an individual ex

The mediating effect of security between impulsive personality and suicide risk was 15.75%. The adolescent emotions are characterized by polarized, impulsive, and irritable behavior with poor self-control, which may cause harmful behaviors when stimulated by stress. Impulsive personality in adolescents with depression has been reported to cause difficulty in adapting to their environment. Lack of security in the face of stressful events results in excessive attention to negative environmental information and a feeling of urgency and anxiousness. As a result, reckless and risky decisions are made, which increases the risk of injury or danger, affects psychological security, and reduces self-control[24]. Therefore, it is recommended that parents of adolescents with depression modify their communication, discipline, and emotional con

In this study, PCSA and sense of security had a 3.15% chain mediation effect between impulsive personality and suicide risk. As a psychological tendency, an impulsive personality makes it difficult for individuals to take the initiative to solve challenges and pressures and to conduct deliberate logical analysis and calm thinking, thus increasing their sensitivity to social adversities[25]. An increase in PCSA further intensifies the psychological pressure on individuals and weakens their sense of security. The sense of security, as an internal feeling of risk premonitions, is negatively correlated with suicide risk. Persistent or repeated negative social events experienced by adolescents with depression may cause them to feel helpless, which weakens their sense of control over their environment and certainty about the future; this leads to a decreased sense of security, which may, in turn, trigger more intense suicidal ideation[26].

It is clinically possible to enhance the sense of security of adolescents with depression by reducing PCSA levels, thereby reducing suicide risk. First, families must strive to enhance their communication and support, reduce conflicts, and help adolescent patients with depression establish a more stable family environment, thereby increasing their sense of security. Second, schools can offer mental health education courses to help adolescent patients with depression enhance their psychological resilience and improve their ability to cope with stress. Moreover, schools should establish a mental health monitoring mechanism to promptly identify and provide interventions for high-risk students. In addition, the community can organize mental health promotion activities to enhance public awareness and understanding of de

This study establishes the chain mediation effect of PCSA and sense of security on the relationship between impulsive personality and suicide risk in adolescents with depression, thereby confirming that impulsive personality can indirectly affect suicide risk in adolescents with depression by regulating PCSA and sense of security. The study limitations are as follows: The sample population was from a single center, and the long study period might have caused selection bias and impacted the study results. In addition, the cross-sectional survey conducted in this study must be validated by multi-center large-sample studies in the future.

| 1. | Shorey S, Ng ED, Wong CHJ. Global prevalence of depression and elevated depressive symptoms among adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Psychol. 2022;61:287-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 804] [Article Influence: 160.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wang L, Xian X, Hu J, Liu M, Cao Y, Dai W, Tang Q, Han W, Qin Z, Wang Z, Huang X, Ye M. The relationship between future time perspective and suicide ideation in college students: Multiple mediating effects of anxiety and depression. Heliyon. 2024;10:e36564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Waraan L, Siqveland J, Hanssen-Bauer K, Czjakowski NO, Axelsdóttir B, Mehlum L, Aalberg M. Family therapy for adolescents with depression and suicidal ideation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2023;28:831-849. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Xin M, Petrovic J, Zhang L, Böke BN, Yang X, Xue Y. Various Types of Negative Life Events Among Youth Predict Suicidal Ideation: A Cross-Sectional Study Based on Gender Perspective. Am J Mens Health. 2022;16:15579883221110352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Carballo JJ, Llorente C, Kehrmann L, Flamarique I, Zuddas A, Purper-Ouakil D, Hoekstra PJ, Coghill D, Schulze UME, Dittmann RW, Buitelaar JK, Castro-Fornieles J, Lievesley K, Santosh P, Arango C; STOP Consortium. Psychosocial risk factors for suicidality in children and adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;29:759-776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Article Influence: 37.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chen R, Hu Y, Shi HF, Fang Y, Fan CY. Perceived chronic social adversity and cyberbullying perpetration among adolescents: the mediating role of rumination and moderating role of mindfulness. Front Psychol. 2024;15:1376347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ding C, Zhang J, Yang D. A Pathway to Psychological Difficulty: Perceived Chronic Social Adversity and Its Symptomatic Reactions. Front Psychol. 2018;9:615. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jin T, Lei Z, Zhang L, Wu Y. Perceived Chronic Social Adversity and Suicidal Ideation Among Chinese College Students: The Moderating Role of Hope. Omega (Westport). 2023;88:638-652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Fung HW, Liu C, Yuan GF, Liu J, Zhao J, Chien WT, Lee VWP, Shi W, Lam SKK. Association Among Negative Life Events, Sense of Security, and Depressive Symptoms in Chinese Adolescents After the 2013 Ya'an Earthquake. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2023;17:e352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Fan H, Xue L, Zhang J, Qiu S, Chen L, Liu S. Victimization and depressive symptoms among Chinese adolescents: A moderated mediation model. J Affect Disord. 2021;294:375-381. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Angst J, Merikangas KR. Multi-dimensional criteria for the diagnosis of depression. J Affect Disord. 2001;62:7-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zhang J, Ding C, Tang Y, Zhang C, Yang D. A Measure of Perceived Chronic Social Adversity: Development and Validation. Front Psychol. 2017;8:2168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Cong Z, An LJ. [Developing of Security Questionnaire and its Reliability and Validity]. Zhongguo Xinliweisheng Zazhi. 2004;18:97-99. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | Lau JH, Jeyagurunathan A, Shafie S, Chang S, Samari E, Cetty L, Verma S, Tang C, Subramaniam M. The factor structure of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11) and correlates of impulsivity among outpatients with schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders in Singapore. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22:226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kliem S, Lohmann A, Mößle T, Brähler E. German Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (BSS): psychometric properties from a representative population survey. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Grossberg A, Rice T. Depression and Suicidal Behavior in Adolescents. Med Clin North Am. 2023;107:169-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 25.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Fu C, Li C, Zheng X, Wei Z, Zhang S, Wei Z, Qi W, Lv H, Wu Y, Hu J. Relationship between personality and adolescent depression: the mediating role of loneliness and problematic internet use. BMC Psychiatry. 2024;24:683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yu X, Zhao J. How rumination influences meaning in life among Chinese high school students: the mediating effects of perceived chronic social adversity and coping style. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1280961. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Shao C, Wang X, Ma Q, Zhao Y, Yun X. Analysis of risk factors of non-suicidal self-harm behavior in adolescents with depression. Ann Palliat Med. 2021;10:9607-9613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Eweida RS, Hamad NI, Abdo RAEH, Rashwan ZI. Cyberbullying among Adolescents in Egypt: A Call for Correlates with Sense of Emotional Security and Psychological Capital Profile. J Pediatr Nurs. 2021;61:e99-e105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Niu G, He J, Lin S, Sun X, Longobardi C. Cyberbullying Victimization and Adolescent Depression: The Mediating Role of Psychological Security and the Moderating Role of Growth Mindset. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jankowski MS, Erdley CA, Schwartz-Mette RA. Social-cognitive risk for suicide and new relationship formation: False perception, self-fulfilling prophecy, or both? Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2021;51:416-428. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Janackovski A, Deane FP, Kelly PJ, Hains A. Temporal exploration of the interpersonal theory of suicide among adolescents during treatment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2022;90:682-695. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Cao L. The Relationship Between Adjustment and Mental Health of Chinese Freshmen: The Mediating Effect of Security and the Moderating Effect of Gender. Front Public Health. 2022;10:916329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Gratz KL, Kiel EJ, Mann AJD, Tull MT. The prospective relation between borderline personality disorder symptoms and suicide risk: The mediating roles of emotion regulation difficulties and perceived burdensomeness. J Affect Disord. 2022;313:186-195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Leichsenring F, Fonagy P, Heim N, Kernberg OF, Leweke F, Luyten P, Salzer S, Spitzer C, Steinert C. Borderline personality disorder: a comprehensive review of diagnosis and clinical presentation, etiology, treatment, and current controversies. World Psychiatry. 2024;23:4-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/