Published online May 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i5.104979

Revised: February 19, 2025

Accepted: March 12, 2025

Published online: May 19, 2025

Processing time: 112 Days and 17.2 Hours

Uncertainty in illness (UI) and fear of progression (FoP) are significant psychological challenges for lung cancer patients. Coping styles and social support are critical mediators, influencing patients' ability to manage the emotional and psy

To investigate the association between UI and FoP among patients with lung cancer.

Convenience sampling was used to recruit inpatients diagnosed with lung cancer at a tertiary hospital in Changde City between November and December 2023. A total of 320 participants completed the Mishel Uncertainty in Illness Scale, Simp

The results revealed that UI had a significant direct effect on FoP (effect = 0.224, 95%CI: 0.136-0.408). Additionally, three indirect pathways were identified: (1) Social support (effect = 0.128, 95%CI: 0.045-0.153); (2) Coping style (effect = 0.115, 95%CI: 0.048-0.157); and (3) Chain mediators involving social support and coping style (effect = 0.072, 95%CI: 0.045-0.120). The total indirect effect of the three mediation paths is 31.5%. These results confirm that social support and coping style significantly mediate the relationship between UI and FoP.

Based on cross-sectional data and a chain mediation model, this study explored the mechanisms between UI, social support, coping style, and FOP. Patients with lung cancer have higher levels of FOP, and the results of this study revealed a correlation between these four factors. Social support and coping style partially mediated the effects of UI on FOP, and there was a chain-mediating effect between UI and FOP. Programs designed to strengthen social support networks should also incorporate training to develop adaptive coping strategies, ultimately reducing FOP and improving overall quality of life.

Core Tip: Fear of progression (FoP) is a prevalent psychological concern among lung cancer patients, closely associated with uncertainty in illness (UI). Social support and coping styles are critical factors that can mitigate the impact of UI on FoP. This study analyzed data from 320 Chinese lung cancer patients to investigate the chain mediation effects of social support and coping styles. The findings highlight that social support and adaptive coping strategies can significantly reduce FoP. This study provides a theoretical foundation for developing psychosocial interventions targeting FoP, emphasizing the importance of strengthening social networks and promoting adaptive coping mechanisms among lung cancer patients.

- Citation: Yang YL, Zhang XQ, Yang YQ, Li EM, Zhou B, Gong YW. Relationship between uncertainty in illness and fear of progression among lung cancer patients: The chain mediation model. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(5): 104979

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i5/104979.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i5.104979

Lung cancer is a leading cause of high cancer incidence worldwide, significantly contributing to cancer-related mortality across various countries and regions. The global death toll from lung cancer has reached 1.8 million, ranking at the top of the list of cancer-related deaths according to data from the 2024 World Health Organization's International Agency for Research on Cancer survey[1]. It has the highest incidence and mortality rate of lung cancer worldwide. Early symptoms of most lung cancers are not obvious; however, they are invasive. When detected, patients are usually in an advanced stage, and treatment results are unsatisfactory, resulting in severe physiological pain and a huge economic burden[2].

Uncertainty in illness (UI) is an emotional state formed when a patient lacks the ability to recognize the disease, such as unawareness of disease knowledge and treatment measures, which may persist throughout the entire illness process[3]. Patients can be subjected to a variety of negative effects when uncertainty emerges[4]. These may not only interfere with the patient's capability to seek knowledge and treatment measures but may also cause anxiety and other negative emotions[4]. Thus, the psychological adaptability of the patient is diminished, and the patient's quality of life is greatly affected, severely affecting the progress of treatments and prognosis for recovery[5].

UI has been proven to be related to the coping choices of patients. Coping is a cognitive behavioral approach indivi

Social support refers to assistance and comfort others provide, particularly during stress or adversity. The presence of social support has been consistently linked to improved mental health outcomes in cancer patients, including reduced anxiety, depression, and fear of progression (FoP)[12]. In lung cancer patients, where the prognosis is often uncertain, the role of social support is even more critical. It helps buffer the emotional and psychological stress associated with the disease, enables patients to engage in healthier coping strategies, promotes resilience, and improves their overall quality of life[13].

FoP refers to psychological fears that individuals feel relating to illness, and it is specifically defined as a variety of social and psychological consequences of fearing disease progression[14]. The occurrence of a high level of FoP is commonly noted among diagnosed patients with lung cancer[2]. A previous study revealed the prevalence of FoP experienced by lung cancer survivors to be in the range of 37%-77.93%[15]. A moderate FoP may prompt patients to be alert to recurrence and help them maintain a healthy attitude, yet an excessive FoP may lead to a series of inappropriate behavioral and cognitive responses that may intensify their psychological distress. Moreover, the administration of chemotherapeutic drugs is typically prone to adverse reactions, bringing additional fear to the patients[16]. Kuang et al[17] performed a study on 102 patients with lung cancer, and their results showed a significantly negative correlation between FoP and quality of life, with higher levels of FoP being accompanied by lower quality of life scores, which is in line with the study by Liu et al[18]. Different coping styles affected patients in different ways. Evidence indicates that patients who engage in avoidant coping styles report higher FoP[19].

Despite growing research on the psychological challenges faced by patients with cancer, there remains a significant gap in understanding the complex interplay between UI and FoP and the mediating role of social support and coping styles. While it is established that patients with cancer experience heightened levels of distress due to the uncertainty of their illness and fear of cancer progression. Most existing research has focused on the direct associations between UI and FoP. Existing research has predominantly focused on Western cancer populations, overlooking potential cultural differences in coping and social support systems among Chinese patients; however, less attention has been paid to the underlying mechanisms that influence these associations[20]. Addressing these gaps will provide targeted psychological interventions for this high-risk population. Social support is frequently cited as a protective factor in cancer patients' emotional well-being; however, its exact role in moderating the impact of UI on FoP is not well defined. Furthermore, although coping styles, whether active (e.g., seeking social support, problem-solving) or passive (e.g., avoidance, denial), are known to influence patients' psychological outcomes, the mediating effect of coping style on the relationship between UI and FoP remains underexplored. While prior studies have separately explored these factors in other cancer types[21], the distinct nature of lung cancer, often diagnosed at advanced stages with poor prognoses, warrants a deeper understanding of how these psychological mechanisms interact. By applying a chain mediation model, this study seeks to bridge this gap, offering a deeper understanding of the psychological experiences of patients with lung cancer and inform interventions that can better support their emotional well-being.

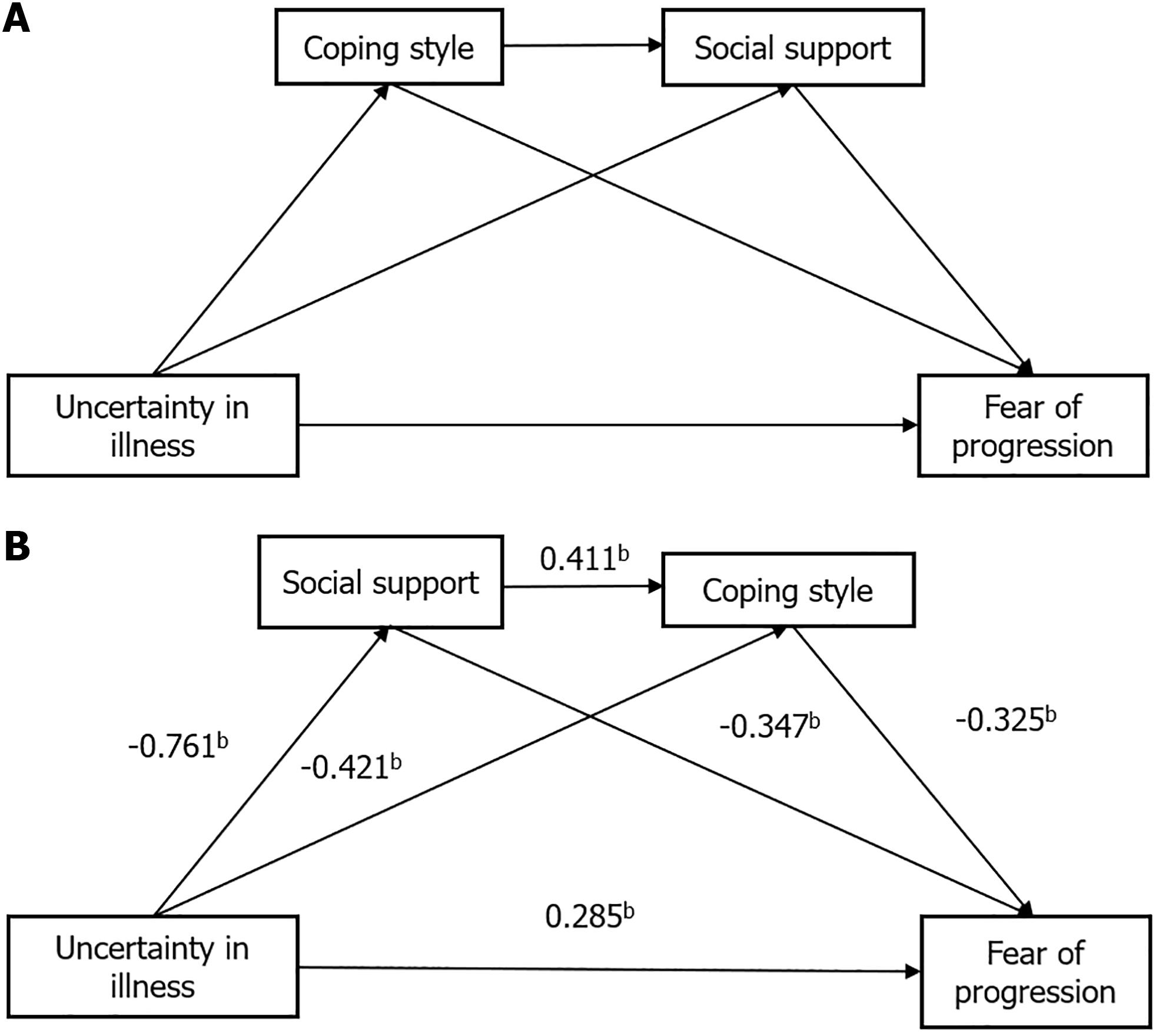

The conceptual model is based on stress-coping theory, which suggests that psychological distress influences coping responses, and social support serves as a protective factor that promotes adaptive coping. Building on previous studies and the stress-coping theory, the conceptual framework (Figure 1) proposes the following hypotheses: (1) There is a significant relationship between social support, coping style, UI, and FoP; (2) Social support and coping style individually mediate the relationship between UI and FoP; and (3) Social support and coping style jointly serve as chain mediators in the relationship between UI and FoP.

Convenience sampling was used to recruit patients diagnosed with lung cancer at a tertiary hospital in Changde City between November and December 2023 as study participants. Inclusion criteria were: (1) Diagnosed with lung cancer confirmed by pathology; (2) Aged 18 years or older; and (3) Able to read and complete the questionnaire independently. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Presence of significant organ insufficiency; and (2) Diagnosis of other cancer types.

The study team and trained research assistants used a unified instruction to introduce the questionnaire research to the hospitalized patients diagnosed with lung cancer, explaining the purpose of the study, and the principle of confidentiality to the respondents, who then completed the questionnaire on their own after obtaining informed consent, and answering the questionnaire without hints in the process of the survey if they encountered any problems that the patients did not understand. If a patient has low literacy or poor eyesight, the research assistants will provide an item-by-item explanation to assist in completing the questionnaire. The questionnaires were collected immediately after they were completed, and the patients were asked to fill in the questionnaires and reconfirm them if necessary, checking for omissions or incorrect items.

To enhance sample diversity and ensure representativeness, stratification strategies were employed based on disease stage, age, and socioeconomic background. To ensure adequate representation of different disease stages, recruitment efforts targeted patients across all lung cancer stages (I-IV). Additionally, age-based stratification was considered to capture a wide range of experiences, with participants distributed across different age groups. Demographic factors such as occupational status, income level, and place of residence (urban vs rural) were also monitored during recruitment to ensure a diverse sample reflective of the broader lung cancer population in China. Patients were recruited from multiple hospital departments, including oncology and pulmonology, to capture variations in treatment settings and disease progression experiences.

The sample size was determined based on the formula for descriptive cross-sectional studies: Based on the preliminary investigation, the mean FoP score of cancer patients was 40.12 ± 7.21[22]. Using these values, the estimated sample size was calculated to be 200. The final sample size was adjusted to 220 participants, considering an estimated non-response or invalid rate of 10%. As a result, 320 valid questionnaires out of 350 distributed, achieved an impressive valid recovery rate of 91.4%.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics: The sociodemographic characteristics included sex, age, educational level, occupational status, income, marital status, residence, and cancer stage.

Mishel uncertainty in illness scale: In this study, we used the Mishel uncertainty in illness scale originally developed by Mishel et al[23] in 1987 and later adapted by Ye et al[24] for patients with tumors. The revised version includes 20 items distributed across three dimensions: Ambiguity, lack of clarification, and unpredictability. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale, yielding a total score between 20 and 100. Higher scores signified increased uncertainty regarding illness. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for this scale was 0.83, indicating good reliability. To ensure content validity, oncology specialists and psychologists reviewed the translated items to verify their appropriateness for lung cancer patients.

Chinese Mandarin version of the medical outcomes study social support survey: The medical outcomes study social support survey (MOS-SSS-CM), originally developed by Sherbourne and Stewart[25] and later translated by Yu et al[26] in 2004, has proven to be reliable and valid within the Chinese population. The scale comprises 20 items, the first of which assesses the size of the social support network (number of confidants). The remaining 19 items span four dimensions: Practical support (four items), informational and emotional support (eight items), social interaction and cooperation (four items), and emotional support (three items). Rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “not at all” to 5 = “all the time”), the scale’s total score ranges from 19 to 95, with higher scores indicating stronger social support. The first item served only as an indicator of network size and was not scored. The MOS-SSS-CM demonstrated excellent internal consistency in this study, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.971, reflecting high reliability compared with the original study’s coefficient of 0.889. The adaptation process included forward-backward translation by bilingual experts and pilot testing with 30 cancer patients to ensure cultural relevance. Minor modifications were made to reflect local expressions of social support.

The simplified coping style questionnaire: The simplified coping style questionnaire (SCSQ) developed and refined by Xie[27] evaluates the cognitive and behavioral coping approaches that patients adopt in response to stress, distinguishing between positive and negative coping strategies. The SCSQ contains 20 items rated on a 4-point scale (0-3), from “do not adopt” to “often adopt.” Items 1-12 assess positive coping, with scores ranging from 1 to 36, while items 13-20 evaluate negative coping, with scores between 0 and 24. Higher scores reflected a greater likelihood of adopting the respective coping styles. The scale had a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.78, indicating acceptable internal consistency. The scale’s content validity was confirmed through expert evaluation, and previous studies have demonstrated its construct validity in cancer populations.

FoP questionnaire-short form: The FoP questionnaire-short form (FoP-Q-SF) originally developed by Mehnert et al[28], is a tool for assessing psychological fear of disease progression in patients with cancer and chronic diseases. Wu et al[29] adapted this scale for use in China, where it was validated with good internal consistency, showing a Cronbach’s α of 0.883. The FoP-Q-SF includes 12 items across two dimensions: Physical Health (six items) and Social Family (six items). Specifically, items 1-3, 5, and 9-10 represent the Physical Health dimension, whereas items 4, 6-8, and 11-12 represent the Social Family dimension. Each item is scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1-5 points), yielding a total score ranging from 12 to 60. Higher scores reflect a more severe fear of disease progression, with scores below 34 indicating functional fear and 34 or above suggesting dysfunctional fear. The adaptation process followed international guidelines for cross-cultural validation, including forward-backward translation and cognitive debriefing with cancer patients. Items were refined based on patient feedback to improve clarity.

Data was analyzed using IBM SPSS software (version 26.0; IBM Corp.). Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data based on the distribution characteristics. Measurement data conforming to a normal distribution were presented as mean ± SD. Categorical data are summarized as frequencies and percentages. The relationships between UI, coping style, social support, and FoP in patients with lung cancer were assessed using Pearson’s correlation analysis. Statistical significance was set at P = 0.05. A chain mediation analysis was conducted using the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Model 6) to examine the mediating roles of coping styles and social support in the relationship between illness uncertainty and FoP. The Bootstrap mediating effect test method was used for further verification. Repeated sampling was set 5000 times, a non-parametric test for bias correction was selected, and bootstrap 95%CI did not contain 0. The difference in the mediating effect was statistically significant.

This study was approved by The First People’s Hospital of Changde City’s Ethics Committee (Approval No. YX-2023-280-01). This study adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and complied with all the applicable guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before their participation.

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the lung cancer patients are summarized as follows: Among the patients, 134 (41.8%) were aged 40-49 years, 147 (45.9%) were aged 50-59 years, and 39 (12.3%) were aged 60 years or older. Regarding Occupational status, 64 patients (20%) were unemployed, 160 (50%) were employed, and 96 (30%) were retired. The distribution of cancer stages was as follows: 36 (11.2%) patients were Stage I, 171 patients (53.5%) were Stage II, 68 (21.3%) were Stage III, and 45 (14%) were Stage IV (Table 1).

| Characteristics | Variable | Frequency | Percent (%) |

| Gender | Male | 177 | 55.3 |

| Female | 143 | 44.7 | |

| Age | 40-49 | 134 | 41.8 |

| 50-59 | 147 | 45.9 | |

| > 60 | 39 | 12.3 | |

| Educational level | Primary or below | 87 | 27.2 |

| Junior high | 131 | 40.8 | |

| Senior high | 61 | 19.1 | |

| University or above | 41 | 12.9 | |

| Occupational status | Not working | 64 | 20 |

| working | 160 | 50 | |

| Retired | 96 | 30 | |

| Income | Low-income | 154 | 48.1 |

| Middle-income | 159 | 49.8 | |

| High-income | 7 | 2.1 | |

| Marital status | Married | 308 | 96.3 |

| Divorced/widowed | 12 | 3.7 | |

| Residence | Rural | 144 | 45.1 |

| Urban | 176 | 54.9 | |

| Cancer stage | Stage I | 36 | 11.2 |

| Stage II | 171 | 53.5 | |

| Stage III | 68 | 21.3 | |

| Stage IV | 45 | 14 |

UI (r = 0.724, P < 0.01) was positively correlated with FoP, whereas social support (r = -0.791, P < 0.01) and coping style (r = -0.741, P < 0.01) were negatively correlated with UI. Social support (r = -0.746, P < 0.01) and coping style (r = -0.635, P < 0.01) were negatively correlated with FoP. The scores and correlations between the variables are listed in Table 2.

Model 6 in the SPSS PROCESS macro was used to test the chain mediation model to examine the chain mediation effect of social support and coping style on the relationship between UI and FoP. Table 3 presents the results of the regression-based analysis. As shown in the table, UI was negatively associated with social support (β = -0.761, P < 0.001), which in turn was negatively associated with coping styles (β = -0.421, P < 0.001). Additionally, UI directly affected FoP (β = 0.285, P < 0.001), confirming the significant direct pathway between these two variables. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 is supported. Consistent with Hypothesis 2, social support was positively associated with coping styles (β = 0.411, P < 0.001), and coping styles were negatively associated with FoP (β = -0.347, P < 0.001). This suggests that higher levels of social support lead to more adaptive coping styles, reducing FoP. Furthermore, UI was negatively associated with coping styles (β = -0.421, P < 0.001), and coping styles were negatively associated with FoP (β = -0.347, P < 0.001). This formed a chain mediation effect, which supported Hypothesis 3, indicating that coping style mediates the relationship between UI and FoP through the social support pathway. The chain mediation model is presented in Figure 1, illustrating the indirect pathways through social support and coping styles that mediate the relationship between UI and FoP.

| Criterion | Predictors | R | R2 | F | Coefficients | β | t | 95%CI |

| Social support | Uncertainty in illness | 0.811 | 0.657 | 69.147 | -0.290 | -0.761 | -23.634 | -0.245-0.321 |

| Coping style | Uncertainty in illness | 0.805 | 0.648 | 73.362 | -0.162 | -0.421 | -8.643 | -0.221-0.125 |

| Social support | 0.406 | 0.411 | 8.243 | 0.323-0.521 | ||||

| Fear of progression | Uncertainty in illness | 0.901 | 0.811 | 155.673 | 0.045 | 0.285 | 7.415 | 0.031-0.056 |

| Social support | -0.127 | -0.325 | -8.276 | -0.094-0.157 | ||||

| Coping style | -0.138 | -0.347 | -9.679 | -0.162-0.111 |

Table 4 presents the results of the sequential mediation analysis that investigated the indirect effects of UI on FoP through social support and coping styles. The direct effect of UI on FoP was significant (effect size = 0.224, 95%CI: 0.136-0.408). The indirect pathway through social support (UI → social support → FoP) showed a significant but smaller effect (effect size = 0.128, 95%CI: 0.045-0.153). The pathway through coping styles (UI → coping styles → FoP) also demon

| Effect relationship | Effect size | Effect ratio | Boot LLCI | Boot ULCI |

| Total effect | 0.539 | 0.424 | 0.643 | |

| Direct effect | 0.224 | 41.56 | 0.136 | 0.408 |

| Total indirect effect | 0.315 | 58.44 | 0.171 | 0.373 |

| Uncertainty in illness → social support → fear of progression | 0.128 | 23.81 | 0.045 | 0.153 |

| Uncertainty in illness → coping style → fear of progression | 0.115 | 21.25 | 0.048 | 0.157 |

| Uncertainty in illness → social support → coping style → fear of progression | 0.072 | 13.38 | 0.045 | 0.120 |

We employed a chain mediation model to investigate the relationships between coping styles, social support, UI, and FoP. As hypothesized, coping style and social support partially mediated the relationship between UI and FoP. Furthermore, a chain-mediated effect was identified, whereby the coping style and social support jointly influenced the association between UI and FoP.

The FoP scores of 36.3 ± 9.2 observed in this study among Chinese patients with lung cancer were significantly higher than those reported in previous studies[2]. This discrepancy may be partly attributable to the unique psychosocial and physical challenges faced by Chinese patients with lung cancer. Traditional Chinese culture places strong emphasis on family harmony and collective well-being. Patients may experience heightened anxiety about becoming a financial or emotional burden to their families, particularly given the substantial costs associated with cancer treatment[21]. These familial concerns, rooted in cultural expectations of filial piety and duty, can amplify psychological distress and intensify fears about disease progression. Furthermore, cultural taboos surrounding discussions of illness and death may discourage patients from openly expressing their fears[17]. This lack of open communication can lead to greater internalization of anxiety, further exacerbating feelings of uncertainty regarding their health and future.

The findings of this study indicate a significant positive correlation between UI and FoP in patients with lung cancer. This relationship suggests that as patients perceive greater uncertainty about their illness, their fear of disease progression intensifies[22]. UI arises from factors such as ambiguous symptoms, unpredictable disease trajectories, and a limited understanding of prognosis. In patients with lung cancer, advanced stage at diagnosis, variability in treatment outcomes, and high emotional burden associated with the disease can exacerbate these uncertainties. These factors create a hei

This study found that social support had a 23.81% mediating effect on the relationship between UI and FoP in patients with lung cancer. This underscores the pivotal role of social support in mitigating the psychological burdens of uncertainty and fear. UI often leads to heightened anxiety and fear of the unknown, particularly regarding the disease progression. Social support, whether from family, friends, or healthcare providers, can act as a buffer against these stressors[32]. By offering emotional comfort, practical assistance, and informational resources, social support helps patients navigate the challenges of their illness more effectively. Although social support does not eliminate the impact of illness uncertainty on FoP, it significantly alleviates its intensity. In Chinese culture, where family-centered care and collective well-being are emphasized, social support often assumes a unique character. Family members frequently play a central role in caregiving, decision-making, and emotional reassurance, which may explain the observed strong mediating effect[33]. These findings suggest that interventions aimed at enhancing social support, such as caregiver training, peer support groups, and culturally tailored counseling, could be instrumental in reducing the psychological impact of uncertainty and FoP[34].

This study revealed that coping style mediated 21.25% of the relationship between UI and FoP among patients with lung cancer, highlighting the substantial role of coping strategies in managing the psychological impact of illness uncertainty. This 21.25% mediating effect suggests that coping style plays a key role in reducing the intensity of the relationship between UI and FoP. While coping styles alone do not eliminate the impact of uncertainty on FoP, they significantly contribute to lessening the psychological burden. This finding emphasizes the potential benefits of interventions that enhance patients’ coping skills. Techniques such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, stress management, and problem-solving training could empower patients to adopt healthier coping strategies, thereby reducing the emotional distress linked to uncertainty and FoP[35]. Additionally, investigating how cultural, demographic, and social factors influence the selection and effectiveness of coping strategies could provide further insights into tailoring interventions for different patient populations.

This study found that social support and coping styles collectively had a chain-mediating effect of 13.38% on the relationship between UI and FoP among lung cancer patients. The chain mediation effect reflects the dynamic interaction between external (social support) and internal resources (coping styles). This interconnected pathway suggests that social support not only directly alleviates the impact of UI on FoP but also indirectly influences outcomes by fostering healthier coping mechanisms. This chain effect may be particularly relevant in Chinese culture, where familial and community support are highly valued. Strong social support networks rooted in the cultural norms of collective responsibility and care can bolster patients' confidence in managing their illness-related stress. Consequently, this empowerment may promote the adoption of proactive and constructive coping strategies, further reducing FoP. These findings underscore the importance of integrated interventions that address both social and psychological dimensions of care. Programs designed to strengthen social support networks should also incorporate training to develop adaptive coping strategies, ensuring a comprehensive approach to managing the psychological burden of illness uncertainty.

We verified the conceptual framework and tested the three hypotheses using a chain mediation model. The results indicated that social support and coping style partially mediated, demonstrating their significant contributions to the relationship between UI and FoP. These findings underscore the multifaceted nature of FoP and highlight the importance of addressing intrinsic and extrinsic resources to improve outcomes. Incorporating social support and coping styles into interventions to alleviate FoP could foster a comprehensive and inclusive approach. This study had several notable strengths. This is the first study to explore the chain-mediated effects of social support and coping styles on the relationship between UI and FoP. Second, by integrating social support and coping style as mediating factors, this study offers a novel perspective on the psychological mechanisms underlying these associations.

However, this study had certain limitations. First, as a cross-sectional study, it cannot capture the dynamic evolution of the variables' impact on FoP over time. Additionally, self-reported measures introduce potential recall bias, and the assessment tools are inherently subjective. Future research should address these limitations by conducting multicenter studies with larger sample sizes to enhance generalizability. Furthermore, qualitative and longitudinal approaches can offer deeper insight into the pathways through which disease uncertainty influences FoP. Targeted psychosocial interventions—such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, social support enhancement programs, or coping skills training—should be tested to determine their effectiveness in reducing FoP among lung cancer patients. Implementing and evaluating such interventions would provide actionable insights for clinical practice and patient support programs. Future cross-cultural research is necessary to examine whether the relationships identified in this study hold in Western or other non-Confucian cultural settings, where patient-provider communication, social support structures, and coping strategies may differ. By investigating these dynamics in diverse populations, we can develop more tailored psychological interventions to mitigate FoP in lung cancer patients worldwide.

Based on cross-sectional data and a chain mediation model, this study explored the mechanisms between UI, social support, coping style, and FoP. Patients with lung cancer have higher levels of FoP, and the results of this study revealed a correlation between these four factors. Social support and coping style partially mediated the effects of UI on FoP, and there was a chain-mediating effect between UI and FoP. A key contribution of this study is the chain mediation approach, which advances beyond traditional single-mediator models by illustrating how social support and coping styles interact dynamically to buffer the impact of UI on FoP. This model provides a more comprehensive understanding of psychological adaptation in cancer patients, emphasizing that support networks not only offer direct benefits but also facilitate the development of adaptive coping mechanisms. Programs designed to strengthen social support networks should also incorporate training to develop adaptive coping strategies, ultimately reducing FoP and improving overall quality of life.

| 1. | Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:229-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5690] [Cited by in RCA: 13057] [Article Influence: 6528.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 2. | Chen R, Yang H, Zhang H, Chen J, Liu S, Wei L. Fear of progression among postoperative patients with newly diagnosed lung cancer: a cross-sectional survey in China. BMC Psychol. 2023;11:168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wongkalasin K, Matchim Y, Kanhasing R, Pimvichai S. Uncertainty among patients with advanced-stage lung cancer. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2024;30:160-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kim O, Yeom EY, Jeon HO. Relationships between depression, family function, physical symptoms, and illness uncertainty in female patients with chronic kidney disease. Nurs Health Sci. 2020;22:548-556. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lee I, Park C. The mediating effect of social support on uncertainty in illness and quality of life of female cancer survivors: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18:143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ko E, Lee Y. The Effects of Coping Strategies Between Uncertainty and Quality of Life of Korean Women With Gynecological Cancer: Evaluation of Uncertainty in Illness Theory and Stress and Coping Theory. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2024;47:E84-E95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kim H, Ji W, Lee JW, Jo MW, Yun SC, Lee SW, Choi CM, Lee GD, Lee HJ, Cho E, Lee Y, Chung S. Cancer-Related Dysfunctional Beliefs About Sleep Mediate the Influence of Sleep Disturbance on Fear of Progression Among Patients With Surgically Resected Lung Cancer. J Korean Med Sci. 2023;38:e236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Guan T, Santacroce SJ, Chen DG, Song L. Illness uncertainty, coping, and quality of life among patients with prostate cancer. Psychooncology. 2020;29:1019-1025. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pahlevan Sharif S, Ahadzadeh AS, Perdamen HK. Uncertainty and quality of life of Malaysian women with breast cancer: Mediating role of coping styles and mood states. Appl Nurs Res. 2017;38:88-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ahadzadeh AS, Sharif SP. Uncertainty and Quality of Life in Women With Breast Cancer: Moderating Role of Coping Styles. Cancer Nurs. 2018;41:484-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Guan T, Chapman MV, de Saxe Zerden L, Sharma A, Chen DG, Song L. Correlates of illness uncertainty in cancer survivors and family caregivers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2023;31:242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hermann M, Goerling U, Hearing C, Mehnert-Theuerkauf A, Hornemann B, Hövel P, Reinicke S, Zingler H, Zimmermann T, Ernst J. Social Support, Depression and Anxiety in Cancer Patient-Relative Dyads in Early Survivorship: An Actor-Partner Interdependence Modeling Approach. Psychooncology. 2024;33:e70038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Wang T, Sun J, Gu D, Shen S, Zhou Y, Wang Z. Dyadic effects of social support, illness uncertainty on anxiety and depression among lung cancer patients and their caregivers: a cross-sectional study. Support Care Cancer. 2023;31:402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Coutts-Bain D, Sharpe L, Pradhan P, Russell H, Heathcote LC, Costa D. Are fear of cancer recurrence and fear of progression equivalent constructs? Psychooncology. 2022;31:1381-1389. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lee YH, Hu CC, Humphris G, Huang IC, You KL, Jhang SY, Chen JS, Lai YH. Screening for fear of cancer recurrence: Instrument validation and current status in early stage lung cancer patients. J Formos Med Assoc. 2020;119:1101-1108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Beaver CC, Magnan MA. Managing Chemotherapy Side Effects: Achieving Reliable and Equitable Outcomes. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2016;20:589-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kuang X, Long F, Chen H, Huang Y, He L, Chen L, Xie L, Li J, Luo Y, Tao H. Correlation research between fear of disease progression and quality of life in patients with lung cancer. Ann Palliat Med. 2022;11:35-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Liu QW, Qin T, Hu B, Zhao YL, Zhu XL. Relationship between illness perception, fear of progression and quality of life in interstitial lung disease patients: A cross-sectional study. J Clin Nurs. 2021;30:3493-3505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Myers SB, Manne SL, Kissane DW, Ozga M, Kashy DA, Rubin S, Heckman C, Rosenblum N, Morgan M, Graff JJ. Social-cognitive processes associated with fear of recurrence among women newly diagnosed with gynecological cancers. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;128:120-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Parker PA, Davis JW, Latini DM, Baum G, Wang X, Ward JF, Kuban D, Frank SJ, Lee AK, Logothetis CJ, Kim J. Relationship between illness uncertainty, anxiety, fear of progression and quality of life in men with favourable-risk prostate cancer undergoing active surveillance. BJU Int. 2016;117:469-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zheng W, Hu M, Liu Y. Social support can alleviate the fear of cancer recurrence in postoperative patients with lung carcinoma. Am J Transl Res. 2022;14:4804-4811. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Shen Z, Zhang L, Shi S, Ruan C, Dan L, Li C. The relationship between uncertainty and fear of disease progression among newly diagnosed cancer patients: the mediating role of intolerance of uncertainty. BMC Psychiatry. 2024;24:756. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Mishel MH, Braden CJ. Uncertainty. A mediator between support and adjustment. West J Nurs Res. 1987;9:43-57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Ye ZJ, She Y, Liang MZ, Knobf T, Dixon J, Hu H, Zeng Z, Hu GY, Zhu YF, Qiu HZ. [Revised Chinese Version of Mishel Uncertainty in Illness Scale: Development, Reliability and Validity]. Zhongguo Quanke Yixue. 2018;21:1091-1097. |

| 25. | Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:705-714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3980] [Cited by in RCA: 4504] [Article Influence: 128.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Yu DS, Lee DT, Woo J. Psychometric testing of the Chinese version of the medical outcomes study social support survey (MOS-SSS-C). Res Nurs Health. 2004;27:135-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 147] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Xie YN. [Reliability and validity of the simplified coping style questionnaire]. Zhongguo Linchuang Xinlixue Zazhi. 1998;114-115. |

| 28. | Mehnert A, Herschbach P, Berg P, Henrich G, Koch U. [Fear of progression in breast cancer patients--validation of the short form of the Fear of Progression Questionnaire (FoP-Q-SF)]. Z Psychosom Med Psychother. 2006;52:274-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Wu QY, Ye ZX, Li L, Liu PY. [Reliability and validity of Chinese version of Fear of Progression Questionnaire-Short Form for cancer patients]. Zhonghua Huli Zazhi. 2015;50:1515-1519. |

| 30. | Zhang N, Li H, Kang H, Wang Y, Zuo Z. Relationship between self-disclosure and anticipatory grief in patients with advanced lung cancer: the mediation role of illness uncertainty. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1266818. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Guan T, Qan'ir Y, Song L. Systematic review of illness uncertainty management interventions for cancer patients and their family caregivers. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29:4623-4640. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Melguizo-Garín A, Hombrados-Mendieta I, José Martos-Méndez M, Ruiz-Rodríguez I. Social Support Received and Provided in the Adjustment of Parents of Children With Cancer. Integr Cancer Ther. 2021;20:15347354211044089. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Lau N, Steineck A, Walsh C, Fladeboe KM, Yi-Frazier JP, Rosenberg AR, Barton K. Social support resources in adolescents and young adults with advanced cancer: a qualitative analysis. BMC Palliat Care. 2024;23:193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Otanga H, Semujju B, Mwaniki L, Aungo J. Peer support and social networking interventions in diabetes self-management in Kenya and Uganda: A scoping review. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0273722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Furtado S, Stallworth T, Lee YM, Tariman JD. Stress and Coping: A Literature Review of Everyday Stressors and Strategies to Cope in Pediatric Patients With Cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2021;25:367-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/