Published online May 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i5.103701

Revised: January 24, 2025

Accepted: March 17, 2025

Published online: May 19, 2025

Processing time: 153 Days and 0.2 Hours

Blonanserin, a novel antipsychotic, has demonstrated efficacy in treating both positive and negative symptoms. However, limited research exists on its dose-dependent effectiveness and safety in patients with and without prominent nega

To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of blonanserin monotherapy for first-episode schizophrenia in real-world clinical settings and to explore the efficacy and safety of different doses of blonanserin for patients with PNS and without PNS.

A 12-week, multicenter, prospective post-marketing surveillance was conducted. In this study, we included patients with first-episode schizophrenia who received blonanserin monotherapy. Patients were divided into those with PNS and without PNS, based on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) negative symptoms subscale scores. Additionally, patients were labeled as high-dose and low-dose groups according to the maximum daily dose they received. Effectiveness was assessed using the BPRS, and safety was evaluated through the incidence of adverse drug reactions (ADRs).

A total of 653 patients were included in the analysis, with 613 completing the study. The BPRS total score decreased significantly from 47.94 ± 16.31 at baseline to 26.88 ± 9.47 at 12 weeks (P < 0.001). A significant interaction of PNS × dose × time was observed for BPRS total scores (F = 3.47, P = 0.040) and negative symptom subscale scores (F = 6.76, P = 0.002). In the PNS group, the high-dose group showed greater reductions in BPRS total scores (P = 0.001) and negative symptom subscale scores (P = 0.003) than the low-dose group in week 12. In the without PNS group, no significant difference was observed between the high-dose and low-dose groups at any visit. Most adverse reactions were mild or moderate, with extrapyramidal symptoms (9.3%) being most common; 1.5% of patients gained ≥ 7% body weight at 12 weeks.

Blonanserin effectively alleviated the clinical symptoms of first-episode schizophrenia with an acceptable safety profile. High-dose blonanserin is particularly beneficial for patients with PNS in the acute phase of first-episode schizophrenia. However, due to the limitation of ADR reporting the real world, the ADR incidence observed in this study may be underestimated.

Core Tip: Blonanserin effectively improved the overall and negative symptoms of first-episode schizophrenia with an acceptable safety profile. High-dose blonanserin showed greater efficacy than low-dose for patients with prominent negative symptoms (PNS) without an increase in adverse drug reactions. Conversely, low-dose blonanserin provided comparable clinical improvement and safety compared to high-dose for patients without PNS.

- Citation: Chen LH, Guo Q, Hu Y, Liu XH, Hu H, Chen HY, Liu CP, Li HF, Chen JD, Li GJ. Effectiveness and safety of blonanserin monotherapy for first-episode schizophrenia with and without prominent negative symptoms: A prospective study. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(5): 103701

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i5/103701.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i5.103701

As a chronic and severe psychiatric disorder, schizophrenia affects multiple areas of life, consistently ranking among the top 10 leading causes of global disability[1]. Positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and cognitive dysfunction are broadly recognized as three main categories in the symptomatology of schizophrenia[2]. Emerging evidence underscores the significant impact of negative symptoms on overall disability and quality of life in patients with schizophrenia[3,4]. Approximately half of patients with schizophrenia exhibit at least one moderate negative symptom, with 10%-30% experiencing two or more negative symptoms[5]. Indeed, these symptoms substantially limit the ability of patients, especially those with first-episode schizophrenia, to live independently, perform daily activities, and sustain personal relationships[6-10]. Moreover, there is a notable difference between patients with and without prominent negative symptoms (PNS). A prospective study found that schizophrenia with such symptoms exhibited greater deficits in cognition and motor coordination than those without, and these negative symptoms were stable over time[11]. Further, schizophrenia patients with PNS manifested more impaired reasoning[12] and sensation[13,14] compared to those without. Particularly, for drug-naive first-episode schizophrenia, negative symptoms are correlated with poorer social function[6] and could predict decreased function capacity over time[15,16]. These findings suggest that patients with first-episode schizophrenia with PNS experience more severe impairment and are less likely to achieve remission. Blonanserin, a relatively novel antipsychotic agent, has emerged as a promising treatment for schizophrenia. By modu

However, there is limited research on the efficacy of blonanserin in patients with schizophrenia with and without PNS. Additionally, most existing studies on blonanserin’s efficacy have been limited by small sample sizes of about 300 patients in a Phase 3 study or by the concomitant use of other antipsychotic drugs in a real-world study, with few large-scale investigations conducted without such interference. There is also a paucity of research focusing on first-episode schizophrenia, whose negative symptoms often lead to greater treatment resistance[6,15]. Furthermore, it is widely recognized that the dosage of antipsychotic medication is closely associated with its efficacy and safety profile[26]. A meta-analysis demonstrated that higher doses of antipsychotics generally yield greater efficacy but are also associated with increased side effects[27]. For blonanserin, a study found that medium-to-high doses were more effective than low doses over 12 weeks[28]. But the relationship between dosage and the efficacy on negative symptoms, as well as the interaction between dosage and the presence of PNS, remains unclear.

To address these gaps, this study conducts a post-hoc analysis of a real-world, prospective, multicenter PMS study to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of blonanserin monotherapy for first-episode schizophrenia in real clinical settings and to explore the efficacy and safety of different doses of blonanserin for patients with and without PNS.

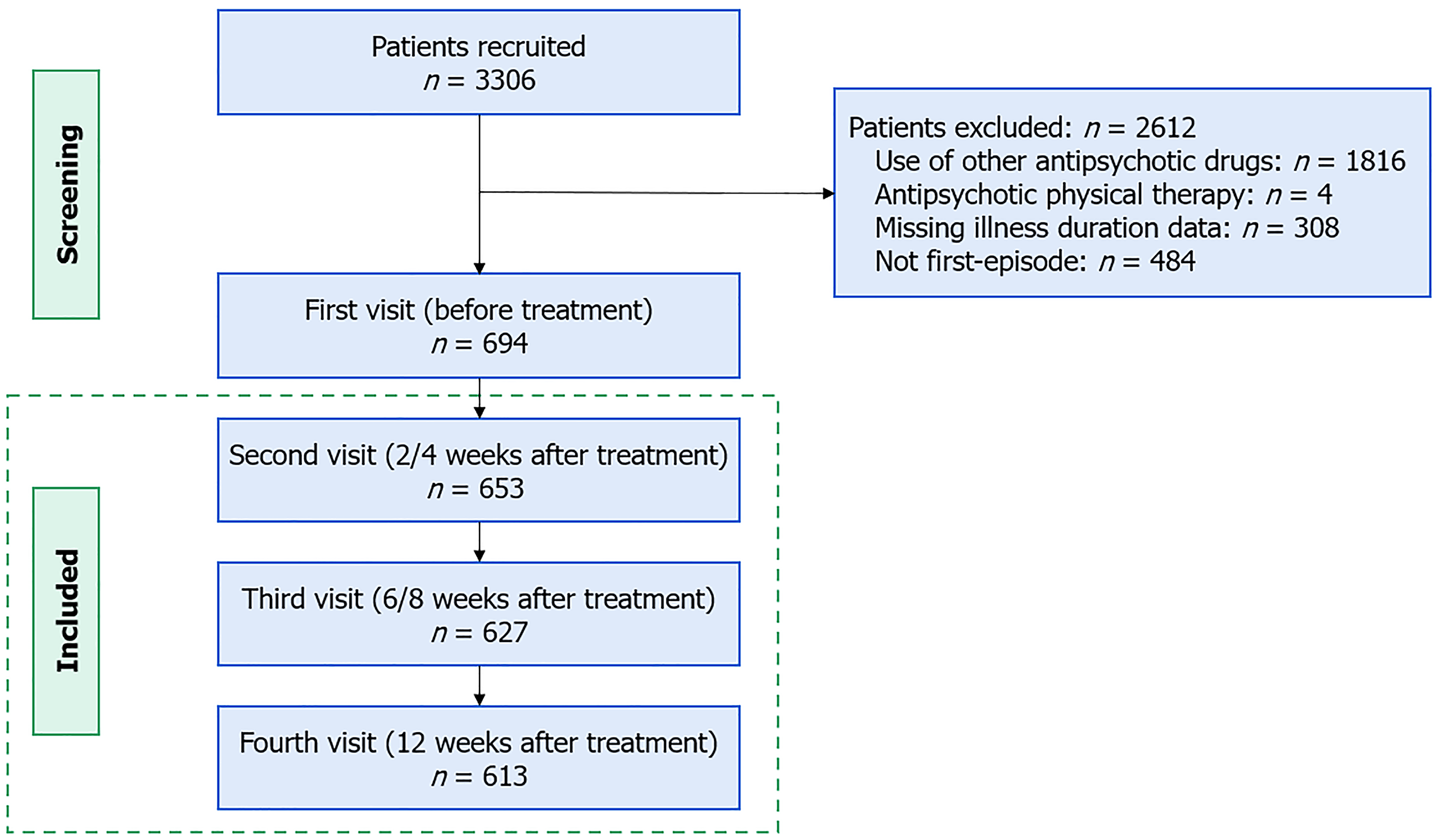

This 12-week, multicenter PMS study was conducted at 31 clinical sites across China, recruiting patients from September 2018 to March 2022. Effectiveness and safety data were collected at baseline, 2/4, 6/8, and 12 weeks. We only included patients with first-episode schizophrenia who received blonanserin monotherapy. Inclusion criteria included meeting the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia and experiencing the first episode of psychosis. Exclusion criteria were the use of other antipsychotic drugs or physical therapy, dropping off before the first follow-up visit (2/4 week), and missing illness duration data. Illness duration was defined as the time from onset of the first psychotic symptoms to the time of study inclusion.

Based on the median scores of negative symptoms subscale of Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) at baseline, patients were divided into two subgroups: Patients with PNS and patients without PNS (non-PNS)[12,13,29]. Specifically, patients with BPRS negative symptoms subscale scores < 9 were assigned to the non-PNS group, while those with scores ≥ 9 were assigned to the PNS group.

Patients were also labeled as high-dose and low-dose groups based on the median of the maximum daily dose of blonanserin they received[30]. Patients receiving < 12 mg/day were placed in the low-dose group, while those receiving ≥ 12 mg/day were placed in the high-dose group. Additionally, patients achieving less than a 40% reduction in BPRS scores were classified as non-responders, while the rest were classified as responders.

The study was approved by the ethics committee at the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (Hunan, China), the leading site for clinical trials (Ethics Approval No. 2018-093). Informed written consent was obtained from all patients following comprehensive explanations, except in cases where consent was waived by the enrolling site.

The severity of schizophrenia was assessed by BPRS[31,32], which consists of 18 items rated on a 7-point scale, resulting in a total score ranging from 18 to 126. The BPRS included five subscales: Positive symptoms, negative symptoms (emo

The primary outcome was the change in BPRS total scores and negative symptoms subscale scores from baseline to weeks 2/4, 6/8, and 12 after treatment. Other BPRS subscale scores were also analyzed. Additionally, the rate of res

During the treatment period, adverse events (AEs) were documented and classified by participating physicians using the ICH International Dictionary of Medical Terms (MEDDRA 21.0, Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities). Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) were defined as AEs for which a causal relationship with blonanserin could not be definitively excluded, as determined by the physicians involved in the study.

Categorical variables are presented as frequencies (percent), and group differences are analyzed using χ2 tests. T-tests were used to compare continuous demographic variables between the PNS and non-PNS groups, and to evaluate differences in blonanserin dosage between responders and non-responders. Three-way mixed analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was employed to examine the effects of PNS and dose on changes in BPRS total scores and negative symptoms subscale scores, controlling for baseline BPRS scores, age, and duration of disease. Missing values were filled out using the last observation carried forward method. Paired t-test was conducted to assess weight gain after treatment. Additionally, a multivariable logistic regression model was employed to investigate differences in ADRs occurrence between the PNS and non-PNS groups, as well as between the high-dose and low-dose groups, with age, sex, and duration of disease controlled. All statistics were computed using SPSS 26.0 software.

A total of 653 patients were enrolled in the study (Figure 1), with 343 having PNS at baseline and 310 without PNS. Of these patients, 276 (PNS: 139; non-PNS: 137) received low-dose blonanserin, and 377 (PNS: 204; non-PNS: 173) received high-dose blonanserin. A total of 613 patients (93.9%) completed the study; however, all 653 patients were included in the effectiveness and safety analysis. Patients who discontinued the study had a mean age of 30.35 ± 12.93 years, with 27.5% (n = 11) being female, a mean illness duration of 40.59 ± 76.18 months, and a mean baseline BPRS total score of 44.60 ± 9.02. No significant differences were observed between completers and non-completers in age. However, patients who dropped out exhibited longer illness duration (t = 40.70, P = 0.048), and there was a higher proportion of males (χ² = 15.09, P < 0.001) and lower baseline BPRS total scores (t = 58.08, P = 0.028).

The baseline demographic characteristics and clinical characteristics of patients are illustrated in Table 1. No significant difference was observed in sex (χ2 = 2.66, P = 0.103) between the PNS and non-PNS groups. However, the PNS group was younger (t = 2.21, P = 0.027) and had a longer duration of disease (t = -2.18, P < 0.001) than the non-PNS group. Moreover, BPRS total score and subscale scores were higher in the PNS group. Age, duration of disease, and baseline BPRS scores were included as covariates in the following analysis.

| n | PNS | n | Non-PNS | N | Total | Statistics | P value | |

| Age, year, mean ± SD | 343 | 32.38 ± 13.77 | 310 | 35.06 ± 16.86 | 653 | 33.66 ± 5.36 | t = 2.21 | 0.027a |

| Sex, female, n (%) | 343 | 193 (56.3) | 310 | 179 (57.7) | 653 | 372 (57.0) | χ2 = 0.14 | 0.704 |

| Weight, kg, mean ± SD | 343 | 61.62 ± 10.44 | 310 | 61.66 ± 10.60 | 653 | 61.64 ± 10.50 | t = 0.04 | 0.967 |

| Height, cm, mean ± SD | 199 | 166.36 ± 7.68 | 156 | 166.48 ± 7.24 | 355 | 166.41 ± 7.48 | t = 0.14 | 0.887 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, mean ± SD | 199 | 22.57 ± 2.84 | 156 | 22.08 ± 3.15 | 355 | 22.35 ± 2.99 | t = -1.54 | 0.124 |

| Duration of disease, month, mean ± SD | 343 | 21.02 ± 56.18 | 310 | 13.26 ± 32.88 | 653 | 17.34 ± 46.72 | t = -2.18 | 0.030a |

| BPRS total score, mean ± SD | 343 | 57.41 ± 14.76 | 310 | 37.46 ± 10.51 | 653 | 47.94 ± 16.31 | t = -20.04 | < 0.001b |

| BPRS negative symptoms subscale, mean ± SD | 343 | 12.30 ± 2.95 | 310 | 6.35 ± 1.36 | 653 | 9.47 ± 3.78 | t = -33.66 | < 0.001b |

| BPRS positive symptoms subscale, mean ± SD | 343 | 13.71 ± 4.23 | 310 | 9.43 ± 3.45 | 653 | 11.68 ± 4.43 | t = -14.25 | < 0.001b |

| BPRS anxiety-depression subscale, mean ± SD | 343 | 11.70 ± 4.21 | 310 | 8.33 ± 3.57 | 653 | 10.10 ± 4.27 | t = -11.06 | < 0.001b |

| BPRS activation subscale, mean ± SD | 343 | 8.10 ± 3.37 | 310 | 5.11 ± 2.39 | 653 | 6.68 ± 3.30 | t = -13.18 | < 0.001b |

| BPRS hostility-suspiciousness subscale, mean ± SD | 343 | 11.59 ± 3.65 | 310 | 8.25 ± 3.17 | 653 | 10.00 ± 3.81 | t = -12.54 | < 0.001b |

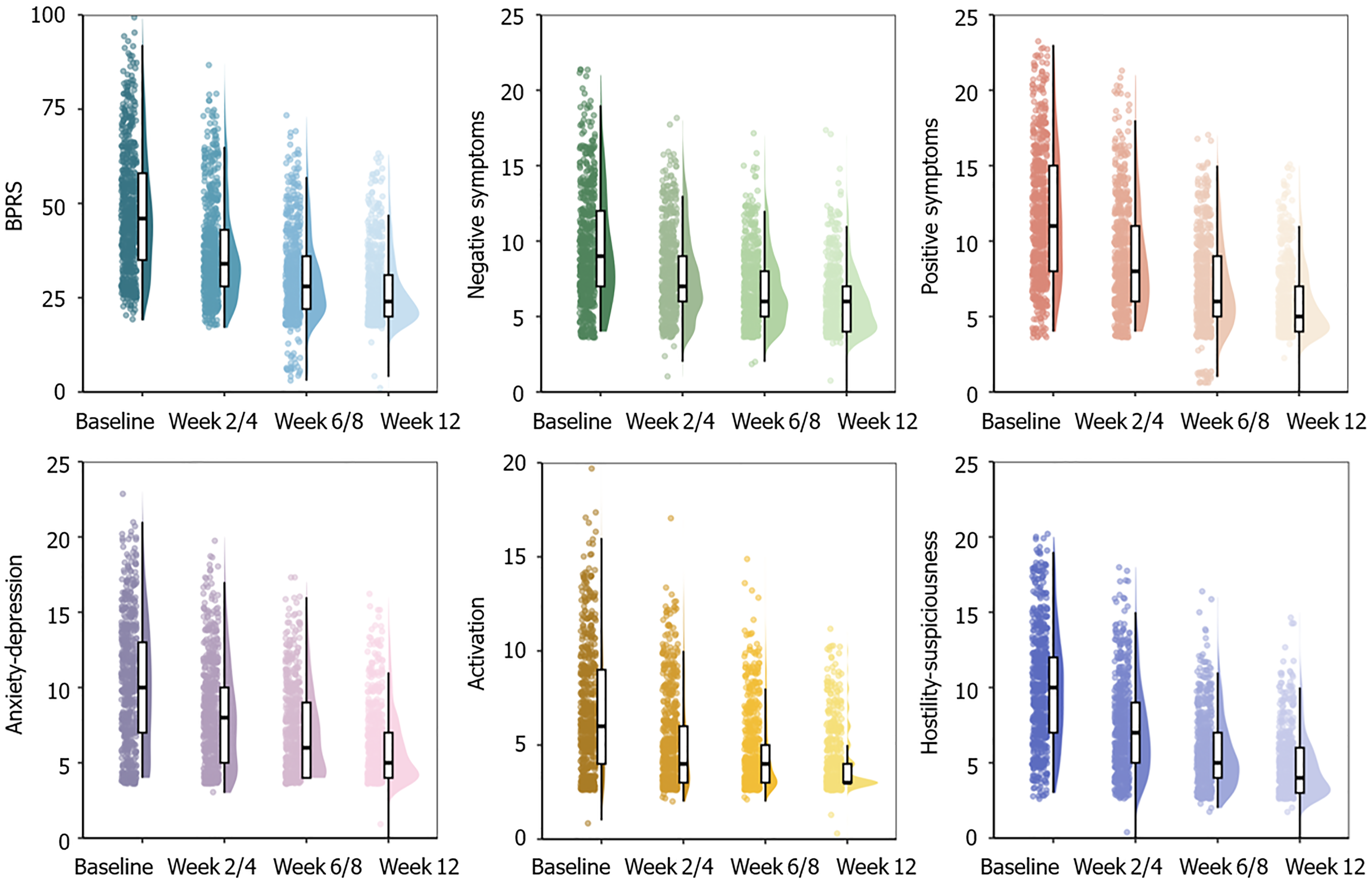

Overall: As illustrated in Figure 2, significant differences in BPRS total score were observed between pre-treatment and post-treatment at each assessment point (all P < 0.001). The baseline BPRS total score was 47.94 ± 16.31 [n = 653, mean ± standard deviation (SD)], which decreased to 37.17 ± 13.31, 31.30 ± 10.86, and 26.88 ± 9.47 at 2/4, 6/8, and 12 weeks, respectively (all P < 0.001 in comparison to the baseline). Approximately 55.9% (365/653) of patients experienced a reduction of 40% or more in BPRS total score in 12 weeks. Comparisons between overall symptoms responders and non-responders showed that responders received a significantly higher dose of blonanserin (t = -2.61, P = 0.009). Specifically, the average maximum daily dosage of responders was 12.92 mg/day, with an SD of 5.22 mg/day (n = 365), while the average maximum daily dosage of non-responders was 11.92 mg/day, with an SD of 4.54 mg/day (n = 288).

Similarly, the BPRS negative symptoms subscale score significantly decreased after treatment at each assessment point (all P < 0.001, Figure 2). The baseline negative symptoms subscale score was 9.47 ± 3.78 (n = 653, mean ± SD), which decreased to 7.79 ± 2.91, 6.77 ± 2.41, and 5.96 ± 2.14 at 2/4, 6/8, and 12 weeks, respectively (all P < 0.001 compared with baseline). Also, 42.7% (278/653) of patients decreased over 40% in negative symptoms score after 12 weeks of treatment. Comparisons between negative symptoms responders and non-responders also showed that responders received a higher dose of blonanserin (t = -2.42, P = 0.016). Specifically, the average maximum daily dosage of responders was 13.03 mg/day, with an SD of 5.26 mg/day (n = 279), while the average maximum daily dosage of non-responders was 12.06 mg/day, with an SD of 4.68 mg/day (n = 374). Besides, as illustrated in Figure 2, scores of the BPRS subscales for positive symptoms, anxiety-depression, activation, and hostility-suspiciousness significantly decreased at each visit after treatment (all P < 0.001).

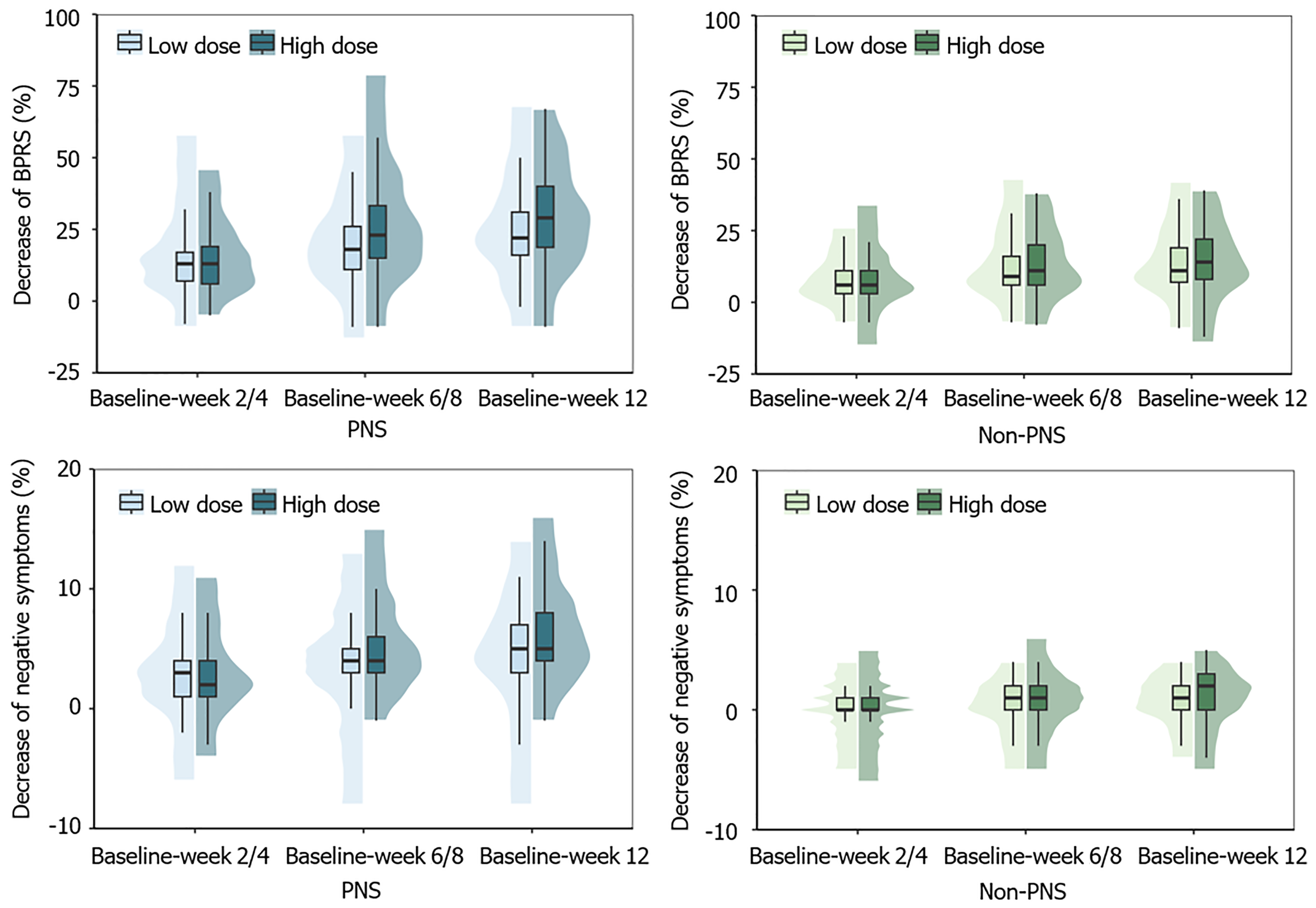

Subgroup analysis: Analysis revealed a significant interaction of PNS × dose × time for the decrease of BPRS total score

For the decrease in BPRS negative symptoms subscale score, a significant interaction of PNS × dose × time was observed (F = 6.76, P = 0.002). For patients with PNS, the high-dose group showed a smaller decrease in weeks 2/4 (P = 0.038) but a larger decrease in week 12 (P = 0.003) compared to the low-dose group (Figure 3). By contrast, the decrease did not differ between dose groups at any visit in the non-PNS group. Besides, a statistically significant interaction of dose and time was observed (F = 8.67, P < 0.001), although there was no significant difference in the post-hoc analysis. For the decrease of other BPRS subscale scores (positive symptoms, anxiety-depression, activation, and hostility-suspi

Safety analysis: Among the 653 patients included in the study, 70 (10.7%) patients reported ADRs. The majority of ADRs was mild or moderate (Table 2). Specifically, 47 patients (7.2%) developed 71 mild ADRs, 24 patients (3.7%) developed 32 moderate ADRs, and 5 patients (0.8%) developed severe ADRs. Notably, no deaths related to blonanserin were reported in the study. Five patients withdrew from the treatment due to adverse reactions.

| Mild | Moderate | Severe | ||||

| Patients | Cases, n | Patients | Cases, n | Patients | Cases, n | |

| Total ADRs | 47 (7.2) | 71 | 24 (3.7) | 32 | 5 (0.8) | 5 |

| Neurological disorders | ||||||

| Akathisia | 24 (3.7) | 25 | 12 (1.8) | 12 | 1 (0.2) | 1 |

| Tremor | 9 (1.4) | 9 | 6 (0.9) | 6 | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Dystonia | 7 (1.1) | 7 | 6 (0.9) | 6 | 1 (0.2) | 1 |

| Parkinsonism | 5 (0.8) | 5 | 5 (0.8) | 5 | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Investigations | ||||||

| Weight gain | 4 (0.6) | 4 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Increased heart rate | 3 (0.5) | 3 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Abnormal liver function | 2 (0.3) | 2 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Sleep disorders | 5 (0.8) | 5 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 3 (0.5) | 3 | 1 (0.2) | 1 | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Kidney and urinary disorders | 1 (0.2) | 2 | 1 (0.2) | 1 | 1 (0.2) | 1 |

The most common ADRs were extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), occurred in 61 patients (9.3%). The incidence of akathisia, tremor, dystonia and Parkinsonism were 5.7% (37/653), 2.3% (15/653), 2.1% (14/653) and 1.5% (10/653), respectively. Regarding weight, the average weight of patients was 61.45 ± 10.37 kg, and was 61.55 ± 10.22 kg in week 12, with no significant intra-group difference (t = -1.32, P = 0.188). In all, 1.5% (9/613) of patients experienced a weight increase of 7% or more in week 12 from baseline. In the multivariable logistic regression model, the interaction of PNS × dose, as well as the main effects of dose and PNS, were all not significant (all P > 0.05), indicating no differences in the occurrence of ADRs between groups.

In this study, we evaluated the efficacy and safety of blonanserin monotherapy for first-episode schizophrenia using data from a 12-week, prospective, single-arm, multicenter PMS study. Blonanserin demonstrated significant efficacy in alleviating the clinical symptoms of first-episode schizophrenia, along with good tolerability and safety. A higher dose of blonanserin was associated with greater improvement in both overall and negative symptoms. Most importantly, we explored the optimal dosage range of blonanserin for patients with and without PNS. For patients with such symptoms, a high dose of blonanserin was more effective in reducing both overall disability and negative symptoms, without an increase in ADRs than low dose. Conversely, for patients without such symptoms, a low dose of blonanserin provided comparable symptom improvement to high dose, while maintaining a similar safety profile.

Patients with first-episode schizophrenia demonstrated great improvements in overall disability and negative symptoms after blonanserin monotherapy treatment, which was consistent with similar studies. Previous small-scale, single-arm clinical trials in China[18] and Japan[25] reported the effectiveness of blonanserin for first-episode schizophrenia. Additionally, several PMS studies have confirmed the efficacy of blonanserin in treating schizophrenia across different sexes or age groups[24,25,34]. A meta-analysis including eight RCTs indicated that blonanserin has comparable efficacy than risperidone[35]. Moreover, previous Phase 3 clinical trials showed that the efficacy of blonanserin is comparable to that of haloperidol[36] and greater than placebo[22], which again proved the efficacy of blonanserin for both positive and negative symptoms.

In this study, we analyzed the daily doses of blonanserin and observed that patients who responded to the treatment received higher doses compared to non-responders, in alignment with previous studies. A PMS study similarly found that a higher dose of blonanserin was associated with greater clinical benefits[28]. Additionally, a meta-analysis suggested that higher dosage of antipsychotics could improve efficacy, particularly in reducing overall and positive symptom scores[27]. To further investigate the efficacy of different doses, we categorized patients based on the presence of PNS.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the optimal dose range of blonanserin for schizophrenia, distinguishing between patients with and without PNS. Our findings indicate a significant interaction between dose and the presence of PNS. High-dose blonanserin (> 12 mg/day) showed greater long-term (week 12) efficacy in both overall disability and negative symptoms for patients with PNS, while low-dose blonanserin exerted similar efficacy than high dose for patients without PNS. Clinical guidelines often recommend the “minimum effective dose”[37,38], particularly for first-episode schizophrenia, to enhance treatment acceptance and reduce side effects[39]. Some studies have investigated the optimal dose of blonanserin. A PMS study involving 364 patients found that a medium to high dose of blonanserin (≥ 16 mg/day) was more effective in reducing overall impairment compared to a low dose, suggesting that this dosage range is suitable for adequate therapeutic level[28]. Additionally, a positron emission computed tomography study with 15 patients indicated that a therapeutic dose over 12.9 md/day of blonanserin was necessary to achieve 70% dopamine D2 receptor occupancy in the striatum, which was required for antipsychotic response[40]. A meta-analysis suggested that low-dose antipsychotic treatment showed an equal efficacy to standard-dose therapy, with no significant difference in overall treatment failure and hospitalization[41]. Few studies have focused on the effectiveness of different doses of blonanserin on negative symptoms. However, studies on other antipsychotic drugs have shown mixed results. For instance, an RCT reported that high-dose Seroquel is superior to low-dose on the modified scale for the assessment of negative symptoms, but not on the negative scale of the positive and negative syndrome scale[42]. Although direct comparisons are not appropriate, the difference between these results may be related to patient heterogeneity. These studies were partially consistent with our finding, but they did not differentiate based on types or severity of symptoms. Our study addressed this gap by comparing patients with and without PNS. As expected, patients with such symptoms required a higher dose of blonanserin to obtain improvements in overall and negative symptoms, while the minimum effective dose may be lower for patients without. This finding is particularly important in light of previous research showing that patients with PNS often experience greater functional impairments, including deficits in cognition[12], sensation[13], and motor coordination[11]. By providing evidence for dose optimization based on symptom profiles, our study offers valuable guidance for tailoring treatment to individual patient needs.

Regarding the safety of 12-week blonanserin monotherapy for first-episode schizophrenia, most AEs were mild to moderate, with a relatively low incidence of severe AEs. The overall incidence of AEs (10.7%) was lower than that reported in Phase 3 clinical trials in China (86.9%)[21]. This discrepancy may attribute to following reasons. First, the Phase 3 clinical trial had stricter monitoring requirements and a smaller sample size, leading to more comprehensive reporting of adverse reactions. By contrast, some minor or short-term adverse reactions may not have been recorded in this PMS study. Second, the PMS study allowed for dosage adjustments based on patient tolerance, while the Phase 3 trial used fixed dose within a predetermined time, which could have exacerbated patient tolerance issues. Nevertheless, the incidence rate in this study is still slightly lower than that reported in a previous PMS study in China (20.1%)[24]. This might be the only study to include patients on blonanserin monotherapy, whereas previous PMS studies included patients on blonanserin combined with other antipsychotic drugs, potentially leading to more AEs.

The most frequently observed adverse reactions of blonanserin were EPS, including akathisia, tremor, dystonia and parkinsonism. This finding aligns with previous studies on blonanserin conducted in China and other countries[24,25,43]. EPS are associated with decreased treatment adherence, increased suicide risk, cognitive dysfunction, and motor skill deficits[44-46], potentially increasing disease-induced disability. The risk of EPS should be considered seriously in clinical practice, which often require additional treatment[47].

We found no significant difference in the occurrence of ADRs across different doses or between patients with and without PNS. Several factors may account for this observation. First, as this study was conducted in real-world clinical settings, physicians had the flexibility to adjust medication dosages in response to ADRs, potentially reducing the dose when AEs occurred. Second, some ADRs may not have been reported by clinicians, which could have obscured potential differences between groups. Previous studies have yielded mixed findings regarding the relationship between anti

Our PMS study indicated that only 1.5% of patients experienced significant weight gain (defined as more than 7%) after 12 weeks of blonanserin monotherapy. Its impact on weight gain is much less compared to other second-generation antipsychotics. For instance, a previous survey reported weight gain exceeding 7% in about one-quarter of patients treated with olanzapine or risperidone, and half of patients with quetiapine over 12-week treatment[48]. Furthermore, a network meta-analysis identified blonanserin as the top-ranked antipsychotic for the lowest risk of weight change among second-generation antipsychotic drugs[49]. These findings suggest that blonanserin is a suitable choice for patients with metabolic syndrome due to its lower impact on body weight.

This study had several limitations. First, this was based only on drug surveillance of blonanserin in patients with schizophrenia, without a control group using other antipsychotics or placebos, preventing a comparison of efficacy with other drugs. Second, cognitive function was not evaluated, so we could not assess blonanserin’s potential benefits in improving cognitive function. Finally, blood drug concentration analysis and positron emission tomography imaging were not conducted in this analysis. Additionally, while ADRs were reported, some minor or short-term adverse reactions may not have been recorded in this PMS study, potentially leading to an underestimation of the overall incidence of AEs. Future studies should include controlled trials with biological assessments and a more comprehensive evaluation of ADRs to validate these findings and refine the optimal dosage for patients with varying characteristics.

In conclusion, blonanserin can effectively improve the clinical symptoms of first-episode schizophrenia with acceptable safety profile. High-dose blonanserin is particularly beneficial for patients with PNS, while low-dose blonanserin is sufficient for patients without PNS. However, due to the limitations of ADR reporting in real-world studies, the ADR incidence observed in this study may be underestimated.

We would like to acknowledge all of the physicians and patients who participated in this surveillance study.

| 1. | Velligan DI, Rao S. The Epidemiology and Global Burden of Schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2023;84:MS21078COM5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sommer IE, Brand BA, Gangadin S, Tanskanen A, Tiihonen J, Taipale H. Women with Schizophrenia-Spectrum Disorders After Menopause: A Vulnerable Group for Relapse. Schizophr Bull. 2023;49:136-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 14.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Best MW, Law H, Pyle M, Morrison AP. Relationships between psychiatric symptoms, functioning and personal recovery in psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2020;223:112-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | McCutcheon RA, Reis Marques T, Howes OD. Schizophrenia-An Overview. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77:201-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 312] [Cited by in RCA: 889] [Article Influence: 148.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Galderisi S, Mucci A, Dollfus S, Nordentoft M, Falkai P, Kaiser S, Giordano GM, Vandevelde A, Nielsen MØ, Glenthøj LB, Sabé M, Pezzella P, Bitter I, Gaebel W. EPA guidance on assessment of negative symptoms in schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2021;64:e23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 27.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cao X, Chen S, Xu H, Wang Q, Zhang Y, Xie S. Global functioning, cognitive function, psychopathological symptoms in untreated patients with first-episode schizophrenia: A cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res. 2022;313:114616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Giordano GM, Caporusso E, Pezzella P, Galderisi S. Updated perspectives on the clinical significance of negative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia. Expert Rev Neurother. 2022;22:541-555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mucci A, Galderisi S, Gibertoni D, Rossi A, Rocca P, Bertolino A, Aguglia E, Amore M, Bellomo A, Biondi M, Blasi G, Brasso C, Bucci P, Carpiniello B, Cuomo A, Dell'Osso L, Giordano GM, Marchesi C, Monteleone P, Niolu C, Oldani L, Pettorruso M, Pompili M, Roncone R, Rossi R, Tenconi E, Vita A, Zeppegno P, Maj M; Italian Network for Research on Psychoses. Factors Associated With Real-Life Functioning in Persons With Schizophrenia in a 4-Year Follow-up Study of the Italian Network for Research on Psychoses. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:550-559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 23.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bucci P, Galderisi S, Mucci A, Rossi A, Rocca P, Bertolino A, Aguglia E, Amore M, Andriola I, Bellomo A, Biondi M, Cuomo A, dell'Osso L, Favaro A, Gambi F, Giordano GM, Girardi P, Marchesi C, Monteleone P, Montemagni C, Niolu C, Oldani L, Pacitti F, Pinna F, Roncone R, Vita A, Zeppegno P, Maj M; Italian Network for Research on Psychoses. Premorbid academic and social functioning in patients with schizophrenia and its associations with negative symptoms and cognition. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;138:253-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Galderisi S, Mucci A, Buchanan RW, Arango C. Negative symptoms of schizophrenia: new developments and unanswered research questions. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5:664-677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 384] [Article Influence: 48.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chan RCK, Geng FL, Lui SSY, Wang Y, Ho KKY, Hung KSY, Gur RE, Gur RC, Cheung EFC. Course of neurological soft signs in first-episode schizophrenia: Relationship with negative symptoms and cognitive performances. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11053. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 12. | Ozguven HD, Oner O, Baskak B, Oktem F, Olmez S, Munir K. Theory of Mind in Schizophrenia and Asperger's Syndrome: Relationship with Negative Symptoms. Klinik Psikofarmakol Bulteni. 2010;20:5-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lui SSY, Chiu MWY, Chui WWH, Wong JOY, Man CMY, Cheung EFC, Chan RCK. Impaired olfactory identification and hedonic judgment in schizophrenia patients with prominent negative symptoms. Cogn Neuropsychiatry. 2020;25:126-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wang J, Huang J, Yang XH, Lui SS, Cheung EF, Chan RC. Anhedonia in schizophrenia: Deficits in both motivation and hedonic capacity. Schizophr Res. 2015;168:465-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chang WC, Ho RWH, Tang JYM, Wong CSM, Hui CLM, Chan SKW, Lee EMH, Suen YN, Chen EYH. Early-Stage Negative Symptom Trajectories and Relationships With 13-Year Outcomes in First-Episode Nonaffective Psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2019;45:610-619. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Vesterager L, Christensen TØ, Olsen BB, Krarup G, Melau M, Forchhammer HB, Nordentoft M. Cognitive and clinical predictors of functional capacity in patients with first episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;141:251-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Deeks ED, Keating GM. Blonanserin: a review of its use in the management of schizophrenia. CNS Drugs. 2010;24:65-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gao T, Deng H, Sheng J, Wu B, Liu Z, Yang F, Wang L, Hu S, Wang X, Li H, Pu C, Yu X. Improvement of social functioning in patients with first-episode schizophrenia using blonanserin treatment: a prospective, multi-centre, single-arm clinical trial. Front Psychiatry. 2024;15:1345978. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Olijslagers JE, Werkman TR, McCreary AC, Kruse CG, Wadman WJ. Modulation of midbrain dopamine neurotransmission by serotonin, a versatile interaction between neurotransmitters and significance for antipsychotic drug action. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2006;4:59-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Harvey PD, Nakamura H, Miura S. Blonanserin vs risperidone in Japanese patients with schizophrenia: A post hoc analysis of a phase 3, 8-week, multicenter, double-blind, randomized controlled study. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 2020;40:63-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Li H, Yao C, Shi J, Yang F, Qi S, Wang L, Zhang H, Li J, Wang C, Wang C, Liu C, Li L, Wang Q, Li K, Luo X, Gu N. Comparative study of the efficacy and safety between blonanserin and risperidone for the treatment of schizophrenia in Chinese patients: A double-blind, parallel-group multicenter randomized trial. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;69:102-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Iwata N, Ishigooka J, Kim WH, Yoon BH, Lin SK, Sulaiman AH, Cosca R, Wang L, Suchkov Y, Agarkov A, Watabe K, Matsui T, Sato T, Inoue Y, Higuchi T, Correll CU, Kane JM. Efficacy and safety of blonanserin transdermal patch in patients with schizophrenia: A 6-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter study. Schizophr Res. 2020;215:408-415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kishi T, Matsuda Y, Nakamura H, Iwata N. Blonanserin for schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis of double-blind, randomized, controlled trials. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47:149-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Wu H, Wang X, Liu X, Sang H, Bo Q, Yang X, Xun Z, Li K, Zhang R, Sun M, Cai D, Deng H, Zhao G, Li J, Liu X, Zhan G, Chen J. Safety and Effectiveness of Blonanserin in Chinese Patients with Schizophrenia: An Interim Analysis of a 12-Week Open-Label Prospective Multi-Center Post-marketing Surveillance. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:935769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Inoue Y, Tsuchimori K, Nakamura H. Safety and effectiveness of oral blonanserin for schizophrenia: A review of Japanese post-marketing surveillances. J Pharmacol Sci. 2021;145:42-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Hui CLM, Lam BST, Lee EHM, Chan SKW, Chang WC, Suen YN, Chen EYH. A systematic review of clinical guidelines on choice, dose, and duration of antipsychotics treatment in first- and multi-episode schizophrenia. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2019;31:441-459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Takeuchi H, MacKenzie NE, Samaroo D, Agid O, Remington G, Leucht S. Antipsychotic Dose in Acute Schizophrenia: A Meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2020;46:1439-1458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Yang Y, Ge H, Wang X, Liu X, Li K, Wang G, Yang X, Deng H, Sun M, Zhang R, Chen J, Cai D, Sang H, Liu X, Zhan G, Zhao G, Li H, Xun Z. Safety and effectiveness of oral medium to high dose blonanserin in patients with schizophrenia: subgroup analysis from a prospective, multicenter, post-marketing surveillance study in mainland China. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2023;22:37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Huber CG, Widmayer S, Smieskova R, Egloff L, Riecher-Rössler A, Stieglitz RD, Borgwardt S. Voxel-Based Morphometry Correlates of an Agitated-Aggressive Syndrome in the At-Risk Mental State for Psychosis and First Episode Psychosis. Sci Rep. 2018;8:16516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Zhang Y, Chen Q, Chen X, Zhang M, Li P, Huang Z, Zhao H, Wu H. The Effect of Intraoperative Fentanyl Consumption on Prognosis of Colorectal Liver Metastasis treated by Simultaneous Resection: A Propensity Score Matching Analysis. J Cancer. 2022;13:3189-3198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Lachar D, Bailley SE, Rhoades HM, Varner RV. Use of BPRS-A percent change scores to identify significant clinical improvement: accuracy of treatment response classification in acute psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatry Res. 1999;89:259-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Raskin A. Discussion: recent developments in ascertainment and scaling of the BPRS. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24:122-124. [PubMed] |

| 33. | Beasley CM Jr, Tollefson G, Tran P, Satterlee W, Sanger T, Hamilton S. Olanzapine versus placebo and haloperidol: acute phase results of the North American double-blind olanzapine trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;14:111-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 522] [Cited by in RCA: 483] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Bo Q, Wang X, Liu X, Sang H, Xun Z, Zhang R, Yang X, Deng H, Li K, Chen J, Sun M, Zhao G, Liu X, Cai D, Zhan G, Li J, Li H, Wang G. Effectiveness and safety of blonanserin in young and middle-aged female patients with schizophrenia: data from a post-marketing surveillance. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23:115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Deng SW, Xu Q, Jiang WL, Hong B, Li BH, Sun DW, Yang HB. Efficacy and safety of blonanserin versus risperidone in the treatment of schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23:740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Harvey PD, Nakamura H, Murasaki M. Blonanserin versus haloperidol in Japanese patients with schizophrenia: A phase 3, 8-week, double-blind, multicenter, randomized controlled study. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 2019;39:173-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Barnes TR; Schizophrenia Consensus Group of British Association for Psychopharmacology. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of schizophrenia: recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25:567-620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 273] [Cited by in RCA: 254] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Keshavan MS, Roberts M, Wittmann D. Guidelines for clinical treatment of early course schizophrenia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2006;8:329-334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Buchanan RW, Kreyenbuhl J, Kelly DL, Noel JM, Boggs DL, Fischer BA, Himelhoch S, Fang B, Peterson E, Aquino PR, Keller W; Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT). The 2009 schizophrenia PORT psychopharmacological treatment recommendations and summary statements. Schizophr Bull. 2010;36:71-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 612] [Cited by in RCA: 652] [Article Influence: 40.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Tateno A, Arakawa R, Okumura M, Fukuta H, Honjo K, Ishihara K, Nakamura H, Kumita S, Okubo Y. Striatal and extrastriatal dopamine D2 receptor occupancy by a novel antipsychotic, blonanserin: a PET study with [11C]raclopride and [11C]FLB 457 in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33:162-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Uchida H, Suzuki T, Takeuchi H, Arenovich T, Mamo DC. Low dose vs standard dose of antipsychotics for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37:788-799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Small JG, Hirsch SR, Arvanitis LA, Miller BG, Link CG. Quetiapine in patients with schizophrenia. A high- and low-dose double-blind comparison with placebo. Seroquel Study Group. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:549-557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 340] [Cited by in RCA: 303] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Garcia E, Robert M, Peris F, Nakamura H, Sato N, Terazawa Y. The efficacy and safety of blonanserin compared with haloperidol in acute-phase schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre study. CNS Drugs. 2009;23:615-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Kapur S, Remington G. Atypical antipsychotics. BMJ. 2000;321:1360-1361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Fervaha G, Agid O, Takeuchi H, Lee J, Foussias G, Zakzanis KK, Graff-Guerrero A, Remington G. Extrapyramidal symptoms and cognitive test performance in patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2015;161:351-356. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Cuesta MJ, Sánchez-Torres AM, de Jalón EG, Campos MS, Ibáñez B, Moreno-Izco L, Peralta V. Spontaneous parkinsonism is associated with cognitive impairment in antipsychotic-naive patients with first-episode psychosis: a 6-month follow-up study. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40:1164-1173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Monteleone P, Cascino G, Rossi A, Rocca P, Bertolino A, Aguglia E, Amore M, Andriola I, Bellomo A, Biondi M, Brasso C, Carpiniello B, Collantoni E, Dell'Osso L, di Giannantonio M, Fabrazzo M, Fagiolini A, Giordano GM, Marcatili M, Marchesi C, Monteleone AM, Pompili M, Roncone R, Siracusano A, Vita A, Zeppegno P, Galderisi S, Maj M; Italian Network for Research on Psychoses. Evolution of antipsychotic-induced extrapyramidal symptoms in patients with schizophrenia in the real-life: A 4-year follow-up naturalistic study. Schizophr Res. 2022;248:279-286. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | McIntyre RS, Trakas K, Lin D, Balshaw R, Hwang P, Robinson K, Eggleston A. Risk of weight gain associated with antipsychotic treatment: results from the Canadian National Outcomes Measurement Study in Schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 2003;48:689-694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Kishi T, Ikuta T, Matsunaga S, Matsuda Y, Oya K, Iwata N. Comparative efficacy and safety of antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: a network meta-analysis in a Japanese population. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:1281-1302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/